Abstract

A national community based participatory research (CBPR) team developed a conceptual/logic model of CBPR partnerships to understand the contribution of partnership processes to improved community capacity and health outcomes. With the model primarily developed through academic literature and expert consensus-building, we sought community input to assess face validity and acceptability. Our research team conducted semi-structured focus groups with six partnerships nation-wide. Participants validated and expanded upon existing model constructs and identified new constructs based on “real-world” praxis, resulting in a revised model. Four cross-cutting constructs were identified: trust development, capacity, mutual learning, and power dynamics. By empirically testing the model, we found community face validity and capacity to adapt the model to diverse contexts. We recommend partnerships use and adapt the CBPR model and its constructs, for collective reflection and evaluation, to enhance their partnering practices and achieve their health and research goals.

Keywords: community and public health, focus groups, participatory action research (PAR), qualitative analysis, reflexivity, relationships, research participation, theory development, trust, validity

Over the last two and a half decades, community based participatory research (CBPR) has increasingly been viewed as an important strategy for eliminating racial and ethnic health disparities through engaging community members as partners in research design, collaborative discourse about knowledge, and in intervention development and health policy-making (Bell & Standish, 2005; Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Collins, 2006; Israel, Eng, Schulz & Parker, 2005; Israel, Eng, Schulz & Parker, 2013; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; Trickett & Beehler, 2013; Viswanathan et al., 2004). The first National Institutes of Health Summit in 2008 on eliminating health disparities highlighted CBPR for its potential to strengthen the translation from science to public health practice and policy (Dankwa-Mullan et al., 2010; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). Despite this recognition and the complementary growth in federal and foundation funding (Mercer & Green, 2008), CBPR studies to date were primarily individual partnership-focused, rather than studies investigating how CBPR partnering processes across a wide spectrum of academic-community partnerships could contribute to improved health outcomes.

In 2006, the University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research (UNM CBPR) partnered with the University of Washington Indigenous Research Wellness Institute (UW IWRI) to launch a national pilot research project to examine the promoters and barriers of successful CBPR partnerships. Over the three project years, the research team, developed and consulted with a national advisory committee (or Think Tank) of CBPR experts composed of a majority of academics with community members from across the country.* The research team conducted an interdisciplinary literature review of collaborative and community engaged research (Wallerstein et al., 2008) and measurement instruments (Sandoval et al., 2011), distributed an internet survey to approximately 100 CBPR projects, and examined survey results in consultation with the national advisory committee. Out of these efforts, we proposed a conceptual/logic model of CBPR partnership processes, which can contribute to CBPR systems and policy changes, and health outcomes (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010; Wallerstein et al., 2008).

Despite the growing documentation of CBPR partnership practices, and to a lessor extent, outcomes (Cargo & Mercer, 2008, Israel et al., 2013; Minkler & Chang, 2013; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008), the development of cross-cutting theory in CBPR has been slow to arrive. To move the field forward, we started with a review of existing CBPR studies and other collaborative public health, social science, and coalition literature (using PubMed, SciSearch, SocioFile databases); the group dynamics literature (using Communication and Mass Media Complete and PsychInfo), the organizational management literature (using Business Source Complete), and indigenous studies and additional colleague recommendations (Wallerstein et al., 2008). With the full methodology and results of this literature review reported elsewhere (Wallerstein et al., 2008), we mention here a few core articles that informed the initial model development: identified CBPR constructs from two earlier reviews (Green et al., 1995; Viswanathan et al., 2004); and the comprehensive dimensions generated by Schulz, Israel, and Lantz (2003), who adapted a validated coalition instrument (Sofaer, 2000), including group dynamics variables (Johnson & Johnson, 1996).

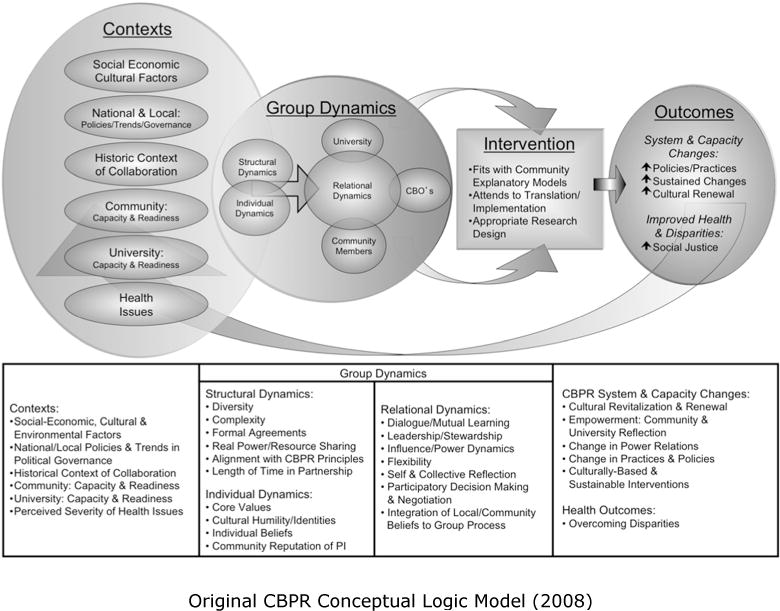

Mapping these constructs onto four overarching dimensions from the literature, our conceptual model proposed that contexts (i.e., contextual factors) ground academic-community group dynamics, which, if they’re effective within their diverse contexts, can impact and change research and intervention designs. The implementation of research and/or interventions in turn can contribute to outcomes, which include broad capacity and system changes, in addition to grant health improvements. (see Figure 1 with four ovals and constructs listed within and under each oval).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Logic Model of Community-Based Participatory Research: Processes to Outcomes (2008)

The first dimension, context, has been an implicit, though not explicit, dimension in earlier CBPR literature, which has focused historically on partnership group processes, rather than contextual factors or outcomes (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Viswanathan et al., 2004; Wallerstein et al., 2008). The model offers therefore an expanded articulation of contextual factors that influence partnerships, including social determinants, such as economic, social, and cultural; environments; local and national policies and funding trends; political governance; historical context of trust/mistrust between universities and communities; and both university and community capacities to engage in participatory research; and salience of health issue to the community.

The second overarching dimension, group dynamics, includes structural, individual, and relational factors. Relationships and partnering processes are probably the most explored within existing CBPR literature, and have the most instruments and measures from multiple disciplines (Pearson et al., 2011; Sandoval et al., 2011). Less explored, but emerging in the CBPR literature, especially within indigenous CBPR where tribal sovereignty is paramount (Walters et al., 2009); and also among publications on CBPR ethics, is the importance of structural agreements among partners to assure community benefit (Flicker, Travers, Guta, McDonald, & Meagher, 2007; Yonas et al., 2013).

The model then suggests that if these structural and relational partnership processes are effective within their dynamic contexts, then partnership decisions would have an impact on and change the third dimension, the research and intervention design. The factors to consider within this dimension include the extent community partners have a voice in how much their cultural norms and knowledge are integrated into the research in designing interventions, methods, or instruments (Dutta, 2007); or the extent of bi-directional translation, implementation and dissemination, so research findings are used. Finally, the ongoing interaction between the context, partnering processes, and culturally-centered implementation of the research or intervention leads to the fourth dimension, outcomes. Outcomes range from intermediate systems, i.e., policy and capacity changes, power relation changes, sustainability, and increased cultural renewal; to improved health and social justice outcomes.

As a first step to integrating collaborative partnering constructs and outcomes beyond a single partnership, this model incorporated multiple theories of change along the socio-ecologic framework (McLeroy et al., 1993), including individual motivations and characteristics, group dynamics and organizational structures, and community capacity processes to create outcomes. To keep the model from being too overwhelming, we chose core constructs to insert in the ovals, with columns under each oval to provide enhanced definitions or specificity.

With the model developed through published literature and expert, primarily academic, consensus-building, we decided to seek additional community input across a diversity of partnerships to assess face validity and acceptability, also known as trustworthiness (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). A subset of the national Think Tank agreed to discuss with their local partners the opportunity to participate in an assessment of the model and its four dimensions. Six partnerships agreed to participate. Four partnerships were local CBPR research projects, three with over 10 years of experience and one a newer three-year research partnership; and two partnerships were national community advisory committees, established over 10 years prior, which had as their mandate the goal to bring community voice into CBPR policy efforts nationwide. The same subset of national Think Tank members solidified the focus group questions, and each member co-facilitated their focus group with their respective partnerships, with an investigator from UNM or UW.

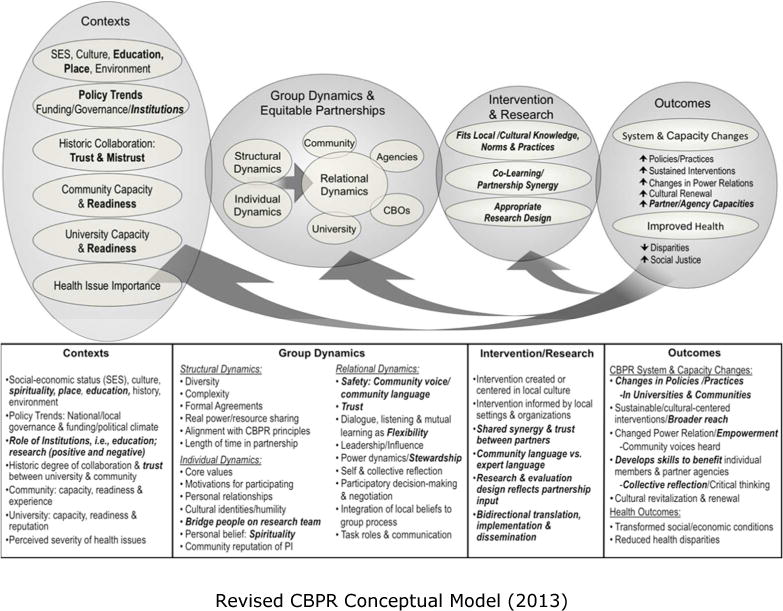

Specifically, the aims of the focus groups were two-fold (a) to gain community partner perspectives on the meanings, strengths and/or weaknesses of the four dimensions and various constructs of the model, and (b) to adapt/revise the model based on community knowledge about the salience of constructs, and on enhanced understandings or new constructs not currently reflected within the model. This paper describes the partnerships that reviewed the model; the focus group methods and guide used (http://fcm.unm.edu/cpr/docs/CBPRmodel-FGguide041612.pdf); and, the results, including the similarities and differences among partnership assessments. We then offer our revised model (see Figure 2) with community face validity, confirming that individual theoretical constructs, pulled from different literatures made sense to community members as a holistic view of how CBPR partnering processes contribute to outcomes. We offer recommendations for how to use and adapt the model and its focus group guide for collective reflection and evaluation of individual partnerships, and for enhancing research and practice within CBPR.

Figure 2. CBPR Conceptual Model: 2013.

Adapted from: Wallerstein, Oetzel, Duran, Tafoya, Belone, Rae, “What Predicts Outcomes in CBPR,” in CBPR for Health From Process to Outcomes. Minkler & Wallerstein (eds). San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2008); and Wallerstein & Duran, CBPR contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health; S1, 2010: 100, S40–S46.

Method

Partnership Sample

A purposive sample (Lindlof & Taylor, 2011) of national Think Tank member’s community partners were recruited, including four local geographic/ethnically diverse partnerships: two in the Midwest (Chicago and rural Missouri); one in the West (San Francisco); and one in the Southwest (rural New Mexico); and two national CBPR non-profit networking and advocacy organizations.

Men on the Move (MOTM)

The Men on the Move partnership developed as a result of conversations within a community-academic partnership that had been in existence for over 15 years between Saint Louis University and rural grassroots heart health coalitions. MOTM is an over 10 year community-based participatory research project funded by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHHD) that addresses the individual, environmental and social determinants of cardiovascular disease within the African American community in Pemiscot County, Missouri (Barnidge, Baker, Motton, Rose & Fitzgerald, 2010; Barnidge, Baker, Motton, Rose & Fitzgerald, 2011; Baker & Motton, 2005; Baker, Motton, Barnidige, & Rose, 2013).

Juan Antonio Corretjer Puerto Rican Cultural Center (PRCC)

The Puerto Rican Cultural Center is a “grassroots, educational, health and cultural services organization founded on the principles of self-determination, self-actualization and self-sufficiency that is activist-oriented” [http://prcc-chgo.org/, accessed 11/12/12], located in Chicago’s near Northwest side. Founded in 1973 to meet the needs of the growing Chicago area Puerto Rican population (Perez, 2004), the PRCC has multiple research partnerships with area Universities. This particular partnership with the University of Illinois has existed since 1995, with a focus on maternal and child health research and service, HIV/AIDS, and more recently, adolescent health and youth-led health promotion (Bozlak & Kelley, 2010; Kelley, Concha, Molina, & Delgado, 2007; Margellos-Anast, Shah, & Whiman, 2008; Peacock et al., 2001).

Chinatown Restaurant Worker Health and Safety Partnership

The Chinatown partnership based in San Francisco, was formed in 2007 to study restaurant worker health and safety and lay the foundation for policy change to improve working conditions in Chinatown’s restaurants. The partnership came to a formal conclusion in 2010. The Chinatown partnership consisted of 18 members, including 12 of Chinese-origin and six Caucasians/non-Chinese Asians, with a core group of current and former restaurant workers, a Chinatown community-based organization, the local department of public health, a university community outreach program, and faculty and students from two universities. Funding support was from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (CDC NIOSH) and The California Endowment foundation (Chang, Salvatore, Lee, Liu, & Minkler, 2012; Chang et al., 2013; Gaydos et al., 2011; Minkler, et al., 2014; Minkler & Chang, 2013; Minkler & Salvatore, 2012; Minkler et al., 2010).

Family Listening Project (FLP) (Tribal)

The Family Listening Project is a research partnership between several rural southwest American Indian tribal communities and the University of New Mexico’s Center for Participatory Research. Since 1999, two tribal communities have been actively involved in at least two National Institutes of Health (NIH) and CDC funded research projects to assess community needs and capacities, with active community boards (English et al., 2004; Oetzel et al., 2011; Wallerstein et al., 2003). The membership of each board has changed over time with the exception of a handful of core individuals who have been active participants over the past years. The NIH-funded FLP grew out of the previous research as an identified need to co-develop and pilot an intergenerational (child/parent/elder) family intervention, building on cultural strengths to reduce risky behaviors in fourth and fifth graders and their families (Belone et al., 2012; Belone et al., in press; Shendo et al., 2012).

National Community Advocacy Networks

In addition to local geographic communities, members from two national community advocacy networks with recruited to participate. The National Community Based Organization Network (NCBON) was formally established in 2004 by the Community-Based Public Health (CBPH) Caucus of the American Public Health Association. NCBON serves as a national hub for community-based organizations (CBOs) and their affiliates, to promote the role of community-rooted interventions and values as the heart of public health. NCBON seeks to enhance capabilities of communities to partner with universities/agencies within their neighborhoods and broader communities; and to act collectively to influence decision-making and policy at a national level through APHA and other venues (http://www.sph.umich.edu/ncbon/). The National Community Committee (NCC) is the community component of the CDC Prevention Research Centers (PRC) Network. In 1999, when only two community members attended the PRC Director’s meeting, it became clear that the community voice was woefully quiet for a CDC-initiative designed to involve communities. The NCC was formed to provide national support, encouragement and training to PRC local advisory boards. Since 2002, the NCC has had a member from nearly every center, has elected leaders, and has held three in-person meetings a year, with aims to bring forth perspectives from diverse communities in the PRC family, and to increase community voice in research. (Collective Voice for Well-Being: The Story of the National Community Committee can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/prc/pdf/prc_collectivevoice.pdf).

We gauged this sample of six partnerships to be appropriate as it represented a diverse set of community partners who had extensive experience with promoters and barriers of successful CBPR partnerships. Appropriateness of the sample is a verification strategy that ensures reliability and validity of qualitative data (Morse, Barrett, Mayan, Olson, & Spiers, 2002).

Participants

The total number of participants was 35, of which 11 were male and 24 were female. We did not collect age of participants, though all were over 18 years old. The ethnicity and region of the participants is displayed in Table 1. Over 90% (32–33) of participants were minority community representatives, though a few were university or agency representatives within the local partnerships. On the whole, we achieved our goal to primarily seek input from community members of each partnership. The local focus groups were conducted with American Indian, African-American, Chinese-origin, Puerto-Rican, Mexican, with a few White community members. The two national network groups were ethnically diverse.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Community Representatives in Focus Groups

| Characteristic | (n=35) | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 11 | 31.4 |

| Female | 24 | 68.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 14 | 40.0 |

| American Indian | 5 | 14.3 |

| Asian | 3 | 8.6 |

| Latino | 6 | 17.1 |

| White | 7 | 20.0 |

| Region | ||

| West | 5 | 14.3 |

| Southwest | 5 | 14.3 |

| East | 2 | 5.7 |

| Midwest | 19 | 54.3 |

| South | 4 | 11.4 |

Setting

Six focus groups were conducted between February and June, 2009: four in-person discussions; and one national focus group using web conferencing or “webinar” technology, and one national conference call. All the in-person participants were provided a copy of the original CBPR model (see Figure 1), while most of the webinar participants logged into a webinar session to review the same model. The telephone-only participants were e-mailed the same model prior to the session. Telephone focus groups have become a practice which has proven to be effective for focus groups brought together over a distance (Allen, 2013).

Data Collection

Focus groups were jointly facilitated by an investigator from UNM or UW, and by the local investigator from each of the four CBPR partnerships and the coordinator of the two national committees (NCBON and NCC) who were also members of the Think Tank. The focus group introduction included the purpose of the group and a review of informed IRB consent for anonymous focus group from the University of New Mexico (HRRC#07-134). Group members then viewed the image of the original conceptual model (see Figure 1) and were given a brief explanation by the focus group moderators. Focus group moderators followed a semi-structured guide that contained open-ended questions assessing perceptions and experiences on the four dimensions of the model (Lindlof & Taylor, 2011). Focus group participants were asked to consider what was important to the current community academic partnership as well as any former partnerships. Further, participants were asked to suggest changes or additions to the model based on their experiences and to comment on the wording and language to ensure that it was clear and understandable to community groups. (Instructions and focus group guide for partnerships to use for evaluation or collective reflection is available [http://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cpbr-project/docs/CBPRmodel-FGguide041612.pdf]) Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently to create a deliberate dynamic interaction between the data, analysis and interpretation. This provided another strategy for data verification and theory development (Morse, Barrett, Mayan, Olson, & Spiers, 2002)

Data Analysis

All focus groups were audio taped, but only five could be transcribed, due to technological difficulties in one of the national webinars, resulting in a poor audio recording. Extensive notes however were taken as back up for each focus group, which enabled all six discussions to be included in the analysis. Focus group participants were provided with their transcriptions or notes and were asked for their feedback.

Each team of focus group facilitators were also the coders and performed multiple readings of their own group’s transcripts and coded the narratives using a matrix/codebook based on components of the model. All new constructs were captured through open coding, including some within the model’s dimensions (see Figure 1) and others that were cross-cutting across the four dimensions. All coders were trained in qualitative analysis and coding, including one community representative who assisted with coding and interpretation processes. All constructs were initially documented on separate matrices for each of the six focus groups. A combined matrix was then developed of verified constructs across the multiple focus groups, as well as any expanded or new constructs that were salient within any individual or multiple focus groups. For each model construct, illustrative quotes were then combined across focus groups to assess common elements of verification, differences between sites, and new or expanded constructs. Figure 2 shows the revised model, with italicized phrases as new or expanded constructs based on the focus group discussions.

Results

Results are reported here by the four dimensions of the model and include verified as well as expanded and new constructs. To illustrate the contribution of all six partnerships in assessing community face validity of each dimension of the model, we provide a summary discussion followed by extensive quotes within matrices (see Tables 2–5) showing how we validated or extended our constructs.

Table 2.

Validated Constructs within Context of the CBPR Revised Conceptual Logic Model 2013

| Social Economic Status/Cultural/Environment | Policy/Governance | Trust/Mistrust | Community Capacity | University Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “We’re always in survival mode how do we get food on the table, how do we clothe ourselves, how do we get our homes? …Those basic processes – just be able to survive – a lot of community are in that mode, so they’re not able to go beyond that some days.” (Tribal) “making sure that there’s a culture, an environment to make the kind of changes we want, need to be in hand and sometimes it’s hard to do that without addressing the socioeconomic barriers.” (MOTM) |

“National and local policy trends and governance [are important]…because in order to promote change and to get to the other side, especially in small areas like this, you have to involve city officials and city government … get their buy-in and you’ll be able to get a lot more help in your community.” (MOTM) “So the governance really matters and the changeover of staff. That’s huge in the ability to do rese arch.” (Tribal) |

“In the past we have seen many other organizations and people coming here. They would use the information they got from this area and do whatever they were gonna do with it and we never got back the results from whatever they were doing. Some of it may have been mistrust.” (MOTM) “I would certainly say that the fact that, P. you had this long-standing relationship with an organization that you actually helped found and the fact that you previously had worked with N and there were all these relationships between various partners that were very strong. There was a lot of trust going and I think we saved a lot of time.” (Chinatown) “Part of trust is also knowing that you’re aware that, you’re mindful of other people’s capacity…that we know that you understand that we’re strapped.” (Chinatown) |

“The reason the cultural center was able to undertake the successful campaign was it was able to draw a vast reservoir of social capital, of trust in the community to say this is what we’re trying to do. It serves as a model to other agencies.” (PRCC) “We have to own that problem to really be effective [in] the outcome. So somewhere in there, we have to say, yes, this is a problem. And trying to get that idea across of, yeah, I’m contributing to it. Now, how can I work on solving it? It’s my problem now.” (Tribal) |

“If the University departments we are partnering with are not ready to work with communities, that could be asking for failure. There are a lot of areas that the University has to learn and grow before they can actually work with the community. So it goes both ways, the reciprocal learning process.” (NCBON) “when you have the Chancellor of the Univ. come visit a program that’s one of the smallest in his school but he personally takes it upon himself to actually give us two graduate assistants, that speaks to how he’s seeing the possibilities of our relationship; in many ways, we also impact organizations that we work with & transform them.” (PRCC) |

Table 5.

Validated, New or Expanded Constructs within Outcomes of the CBPR Revised Conceptual Logic Model 2013

| System Level Changes | Capacity Changes | Policy Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Constructs | “From a historical perspective, for us, the community based organization, it’s like looking at the reasons why we see African American based community organizations come and go, which has to do with them not having the knowledge, skill … they’re not sustainable … It took us a while to get some of the internal controls in place with the financial management piece … It’s not necessarily an easy transition to build capacity… they need to be willing for that to happen, receptive to change.” (MOTM) “… we’re constantly transforming the way that we think, our ideas, where we’re headed, where we’re going, and that’s an important piece to doing this type of work … because we’re changing with the world as well”. (PRCC) |

“Enforcement of these policies really need to be done by the people who are most impacted and I think that that for us is really important. It’s not necessarily community readiness again but I think that’s the closest way to understand it is that it’s like these policies are good, but especially if you have workers to be behind it and be standing confidently behind it.” (Chinatown) “National and local policy trends and governance and that’s because in order to promote change and to get to the other side you have to involve, to me, I think especially in small areas like this you have to involve city officials and city government get their buy-in on things and you’ll be able to get a lot more help in your community.” (MOTM) |

| Expanded or New Constructs | ||

| Expanded Reach: “… It’s already been three years that we have this program and it’s being branched to other communities because it has been a model of what we are doing to fight obesity and diabetes in the process.” (PRCC) | Capacity to Transform University: “So I think that in many ways we also impact on those organizations [universities] that we work with and transform them in some respects…So it’s not when we meet them; it’s after a while; it’s how do they grow or do they grow to respect, learn, you know come closer to the center of the community’s perspective…we’ve been able to obviously break their own paradigms and how they deal with communities and how they come in and treat people …” (PRCC) Empowerment: “This process empowers the community and maybe some researchers are afraid of empowering communities. That’s a possibility. Or because of this whole: if we empower them, then they’re going to take over certain things.” (Tribal) |

Power through Capacity: “Power through Education- You have to have education, but if you play the game right, you can go all the way to change policy to have better outcomes in your native communities … you need to be at the same level to play their game and then try to turn things around to benefit your community.” (Tribal) |

Context

The first dimension (first oval) of context highlights the social, historic and structural factors that influence all subsequent model dimensions, with focus group participants often referring to contextual issues when they talked about the other dimensions, i.e., the importance of historic trust for establishing trust in new partnerships. While for the most part, discussion of context was consistent with expected discourse, such as socio-economic conditions or community capacity, community participants suggested some new language, and nuances in meaning and operationalization of existing constructs to better reflect community perspectives. Table 2 presents validated constructs, and Table 3 presents expanded or new constructs within the context dimension.

Table 3.

New or Expanded Constructs within Context of the CBPR Revised Conceptual Logic Model 2013

| Social Economic Status/Cultural/Environment | Policy/Governance | Trust/Mistrust | Community Capacity | University Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spirituality: “One thing that sticks out to me is religion and spiritual relationships. We’ve had partners who didn’t have that same spiritual background and there was conflict. In this particular group, someone wanted to say prayer and others didn’t and so they decided to do a moment of silence instead, to say that everyone is respectful of everyone else.” (NCBON) Place: “it sounds like geography, natural environments. It’s distance & understanding, literally weather, water… not only existing natural resources, but like the tornados here, the ice storms that clearly affect everything we do.” (MOTM) |

Institutions and Institutional Policies: The role of institutions is not in here. I mean policy is, but whether they’re education or health or research institutions. The trauma of boarding schools is a federal policy issue. (Tribal) School is an institution to go to … We’re placed in this institution, forced. Then after we get finished through high school, then we commit to another institution. We’re insane to go. Those dropouts are more sane than we are … Because if you look at it that way, you can pretty much say everything is connected to historical trauma.” (Tribal) |

Depth of Mistrust as embedded institutionally: “We’ll never have an equitable partnership with institutions, government or universities…I believe research institutions exist to basically be able to systematize the knowledge that they draw from the people that they are supposed to be studying.” (PRCC) Someone is always testing us for something. Let’s not let the community feel like they are just guinea pigs again and when it’s over with, it’s smoke and mirrors again.” (NCBON) |

Readiness: “From my standpoint, you can’t have any of these things unless you have a community ready & wanting to participate. Without community’s input, capacity, and readiness, none of this can be done.” (NCBON) “If we didn’t have some structures in the community, if we didn’t have that CBO to partner with, then we wouldn’t be here. I am so glad that there was community readiness where we could formalize ourselves to have some capacity… to bring this project to the community.” (MOTM) |

The inclusion of socioeconomic, structural, cultural factors within context was often seen as foundational. “The socioeconomic and cultural factors, we found, needed to be addressed before we could move in the way we wanted to move” (MOTM). Yet, participants from rural communities also indicated a new concept of place, not represented in the original model, in terms of distance between partners, natural resource assets and impediments; as well as cultural differences, including how people in rural communities often need time to just talk with each other, versus focusing on tasks. Education was seen to be missing from the socioeconomic/cultural construct, and some participants felt that they wanted to see a stronger emphasis on formal and informal education to really understand what’s going on in their community. In talking about national and local policies, trends and governance, participants highlighted the importance of engaging with political powers to create change in communities, yet suggested a new construct of institutions (e.g., governmental, health, or business), and how negative federal institutional policies, such as boarding schools that prohibited Indian languages and culture, have impacted the development of equitable partnerships.

In every focus group, participants recognized historical context of collaboration, and identified more strongly mistrust of research as a result of direct actions outsiders have taken against communities, as well as acts of omission (e.g., not sharing results). “So that’s how communities look at researchers. What does this person want? … I just think from the past, we’ve just had so many people from (universities) going in wanting to do research and, we never got anything in return” (Tribal). Several partnerships articulated an expanded view of relationship-based proxy trust, with previous relationships facilitating the research partnership, as well as an optimistic view that trust could develop (concepts more explored in next dimension of group dynamics).

The importance of considering a community’s capacity to conduct CBPR was validated in every focus group. Participants elaborated on multiple aspects of capacity, especially the role of respecting and employing community knowledge and preferences, and the importance of strong community organizations. “You gotta have a certain type of capacity and leadership role within the community in order to carry on a lot of the research that been done” (MOTM); and “if we didn’t have that CBO to partner with, we wouldn’t be here” (PRCC). To achieve ownership as an outcome, participants also noted the dynamic quality of community capacity, especially as a developmental process that builds independent capacity among CBOs, community members and the partnership itself. Some talked about their own growth as advisory committee members, including the risks of capacity development in terms of self-identity and treatment by others. “When I get into leadership positions, then there is some disconnect, and I don’t know if they are threatened…but something happens” (MOTM). A tribal focus group succinctly captured both the challenge and the responsibility of greater capacity, “The capacity has been built within me to go back and start questioning things again and really look at these issues and these policies.”

While CBPR literature has often focused on community capacity, participants resonated with the inclusion of university capacity and readiness, not only as a function of individual investigators, but also as inhibiting or supportive institutional policies and practices. Finally, they articulated an expanded view of capacity as readiness, which incorporated community priorities and ownership, “[T]he thing that makes the capacity [is] based really on how ready they are and even if they’re ready, you know, is that really a priority for the people to get involved, you know?” (Chinatown).

Group Dynamics

The second oval, the group dynamics dimension, consists of three sub-dimensions, individual, structural, and relational dynamics, which form core CBPR partnering practices that operate within diverse contexts to produce outcomes. Taken as a whole, the concepts of cultural humility, dialogue/mutual learning, power dynamics, self and collective reflection resonated most immediately with the community informants. Partnership length of time, community reputation of principal investigator (PI), and participatory decision-making were also validated, but not as strongly. Some new or expanded concepts of relational dynamics emerged: (a) the benefits of bridge people who link university and community was explored with greater nuance; (b) flexibility within dialogue and mutual learning; (c) trust development related to safety within partnerships; (d) stewardship towards the community articulated as a shared responsibility and part of equitable power relations; and (e) power in language as core to partnership relationships (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Validated, New or Expanded Constructs within Group Dynamics of the CBPR Revised Conceptual Logic Model 2013

| Individual Dynamics: | Relational Dynamics: Resource Sharing | Relational: Dialogue, Reflection | Relational: Power Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| “So, for me it is very important that whoever comes is able to engage us at least at a level of equity, of equality, … with a sense of humility. And ultimately comes in with the notion that I am here to engage you with the awesomeness of your greatness and not with the awesomeness of what I bring to you. In other words, I believe it should be driven by a sense of solidarity rather than a sense of charity and a sense of really being able to be committed.” (PRCC) “It takes one bad slip up and their name will be ruined, just one little innuendo and, you know, it’s like don’t work with this group of folks…” “If one person does it [makes a mistake]… the whole university will be at fault.” (NCBON) Bridge people: “Well, having your research team, like [Univ. names] native people. Even though they’re not from our community, it’s still was a big comfort. And I think for us, it was bonding-that first connect with us being that she was native. I think it matters a lot. Who you identify with –some shared commonalities with the researcher or with somebody. You have that connection and then you have the bond, the relationship and then you have somebody to work with.” (Tribal) “Our programs are usually focusing on the African American community. And often, PIs are not African-American, so sometimes they don’t think of bringing in African Americans to provide … some locals to do the presentation. Sometimes, we have had to go back and say, we would prefer to have an African American come to this community because our community really do like to see themselves in those positions.” (NCBON) |

“The sharing of resources should be something that is a given… I heard a comment this morning from my local community how one entity wants to do the lion’s share of resources. And we need to make sure that someone in [the] community doesn’t feel shorted out and that there’s good communication as well as transparency in everything that’s being done“ (NCBON) “… there is no openness until they can trust you and so take the time on group dynamics and get to know [each other]” (MOTM) “… what our relationship … it’s created a safety net where we feel free as individuals to be able to do the work that needs to be done in order to meet our goals. But if for some reason we mess up, there is a net there and you helped to really create that, [academic partner’s name]. You helped me to really see that this isn’t about pointing the finger. This is about us getting up and trying to do it better. And that’s like that safety net that we have. We all embrace that.” (MOTM) “But, with the work we’ve been doing with CBPR … and the folks we’ve been working with, it’s been a total turnaround from what we knew, from when we first started working with the university because there was so much bad blood and mistrust.” (NCBON) |

“[There] … needs to be a long process of truly getting to know each other… sometimes researchers don’t build that time and money in their budget. [You] have to come “sit on the porch”… [It’s an] entirely different culture, so try[ing] to meld these two …” (NCC) “… these people that we work with [university researchers] grow to have an appreciation… OK, how do we teach these people to really learn about this? So it’s not when we meet them, it’s after a while, it’s how do they grow or do they grow to respect, learn, you know come closer to the center of the community’s perspective.” (PRCC) Flexibility: “There was one thing around flexibility. [The CBO], for example, at the end of last year … there was all kinds of things going on. The elections was going on…and for the project that there would be the university or the agency would have to be understanding of some of the shifting timetables or other kinds of dynamics – University-community bridge person” (Chinatown) “Has to be a fluid process… Have to be willing to be a back-up … sometimes those concepts don’t fit into [an] institutional model… I feel the consequences of that right now. We did what we said we were going to do, we just didn’t get the response we hoped, and we have to do it again.” (NCC) |

“Part of your colonial reality is the inability to learn to actualize yourself because you’re always told that you have had no history of being able to change things for yourself, that things have to be done by an outsider or outside force. And then you don’t have ownership of your own life and your own destiny and that’s why self-reliance is so important.” (PRCC) “… if you play the game right, you can go all the way to change policy to have better outcomes in your native communities. … You need to be at the same level to play their game and then try to turn things around to benefit your community.” (Tribal) Stewardship/Shared Accountability: “There’s a whole lot of … shared responsibility on all parts, from the University’s perspective, from the community’s perspective, from the health department’s perspective, and all involved to make sure that none of the old wounds are reopened.” (NCBON) “We have had instances where University, and community person pulled together a presentation and…that community presenting in class on the project … which is something new. It’s a shared leadership … In turn, the community partner would have someone from the University come down to the community and introduce them and tell them what they’re doing … from the community perspective.” (NCBON) |

Individual Dynamics and Characteristics

Several individual characteristics were named as important: cultural humility (and general humility); and community competence as a journey rather than an endpoint (Selig, Tropiano & Greene-Moton, 2006). The sometimes-delicate nature of relational dynamics was noted within the community reputation of principal investigator construct. One respondent felt that a single researcher “slip up and their name will be ruined, just one little innuendo” could damage the willingness of the community to partner with that individual and others at the university.

The importance of the concept of bridge person was strongly verified by several community focus groups, and expanded in greater nuance. Community members identified bridge people as individuals on academic teams who shared race/ethnicity characteristics with community partners; bridge people were often identified as students, or sometimes as community members hired as staff by the University to serve this role. Lack of a bridge person was considered evidence of low university capacity, even while acknowledging the reality of few scholars of color in academia. Shared cultural identity was described as engendering trust development and facilitating mutual core values and integration of local knowledge into collective work. On the other hand, a community-university bridge person described the internal tensions, stress and conflicts of trying to hold values and aspirations of both university and community.

When asked directly about what was missing from the model, some of the focus groups noted that although culture was represented, spirituality needed to be added, as distinct from culture and religion, even with differences of expression across communities. “We’re in the Bible belt; people are connected to the land. If you don’t include spirituality, we’re missing the boat” (NCC). “Spirituality – we always talk about that. I mean it’s kind of related to religious institutions too but spirituality, in general, has a lot to do with the way the community operates” (Tribal).

Structural Dynamics

The structural dynamics were least discussed, though diversity was expanded to include diversity of place, i.e., rural versus urban, in addition to diversity by race/ethnicity. Budget sharing was verified as an important structural marker of equality/inequality in the partnership.

Relational Dynamics

Trust Development and Safety in Partnerships

Although trust was identified in the original model as contextual, participants expanded the discussion to trust throughout the model and especially an essential part of partnering group dynamics. Trust was viewed as a fluid and evolving concept, earned by experience, such as “following-through, keeping promises;” trust was seldom bestowed without merit. Many believed trust towards individual investigators and staff developed over time, but a sense of mistrust and/or uncertainty towards the university or institution of research often persisted. Community members often returned to talking about the historic context of university separation and aloofness from everyday community problems. Safety was added as being related to the development of trust. While many participants verified length of time as important for developing trust and safety, one project stated that formal organizational processes, i.e., memoranda of agreements, were helpful while another described their organic/informal process as being critical for trust development. Trusting and safe environments were attributed, in part, to an academic partner’s interpersonal skills, and to relationships developed with individual partners.

Dialogue, Self- and Collective-Reflection, and Mutual Learning

Mutual learning and self/collective reflection were verified as important elements and built on a foundation of safety and reciprocity. Some indicated that formal collective reflection was a sign of growing safety among individuals and with groups. One group valued ongoing mutual learning as “reciprocal interaction.” Flexibility was expanded as an important aspect of mutual learning, both as the response to partnership changes, such as staff and leadership changes, as well as in response to community vicissitudes and other priorities. In the Chinatown partnership, for example, university researchers needed to be flexible during election time and sensitive to competing priorities within the community or to CBO partner changes.

Power Dynamics

Repeatedly, acknowledging differences in power was endorsed as important. Historical relationships were an important context for discussion of power, with resource distribution and vocabulary hierarchies being concrete examples of how power inequities between partners were organized. A community member questioned the ability of CBPR to be genuinely equitable in power relations due to the historical experiences with research, i.e., “just being a subject.” Colonialism as a root of these power differentials was mentioned by some in their understanding of how science has been used as a tool of colonization in their communities’ history. Across the discussion, a nuanced edge between cooperation and co-optation was identified. One community member stated, “the more you develop these relationships with larger institutions, you have to maneuver inside that framework, as well as outside of it. Sometimes these frameworks contradict each other, and you have to figure out what you are willing to give and…what principles you’re willing to keep.” This boundary tension or stress was repeated in a discussion of the bridge person, as having both “insider and outsider” roles.

A new element of power within the model was the notion of stewardship or shared responsibility, including the responsibility to leverage power overtly and covertly for community interests. Community members, who were typically service-providers or involved in advocacy and new to research, often expressed surprise at the university’s interest in community problems; they hoped both the university and community would share responsibility for assuring research benefit. One group named this CBPR shared responsibility as a research ethic distinct from past helicopter research (Greene-Moton, Palermo, Flicker & Travers, 2006). Community members expressed that an important role of both university and community staff who acted as bridge people was to hold university researchers accountable for promises to the community. A good academic partner was seen as someone who would use their social capital i.e., access to technical or financial resources, for the benefit of communities and agencies.

Also new were the issue of language and the perception of inequality of who has power and legitimacy to express their opinions (Mirowski & Plehwe, 2009). Community members expressed concerns that their language was discounted and ignored, while the academic person’s views were heard and valued. As one participant said “she [the community member] didn’t say it in the exact large words that the other [university professor] said, but she said exactly the same thing…that can be frustrating sometimes ‘cuz that means that the community members’ opinion wasn’t validated. Was that because they didn’t have a PhD? Was it because their opinion wasn’t seen as something that was appropriate or right?” (NCBON). An example of successful broadening of language in both academic and community venues was attributed to partners presenting together at conferences and including the knowledge and language of the respective partner. One focus group described translation of science to the community and vice versa as a process of mutual learning.

Research and Intervention

For the third dimension, research and intervention, not all of the communities were engaged in interventions at the time of the focus group, which resulted in less discussion about this dimension. For the communities that did comment, however, we heard that intervention research created the practice for mutual learning. Intervention research could also be organic, resulting in a community-appropriate design that considered cultural knowledge, norms, and practices. The original model’s use of technical research vocabulary in this section however was critiqued as being the most difficult.

The tribal advisory group, which was actively engaged in co-creating and evaluating a cultural intervention, commented on how intervention development allowed for reciprocal learning. “So one of our values is on-going mutual learning; that’s a value that I’m learning. You’re not the only ones learning; I’m also learning, and it’s ongoing. It’s an on-going learning that we’re doing together. There’s another word to describe it; I use it in a parent child relationship. It is reciprocal, yeah reciprocal interaction.”

For the Puerto Rican community, intervention research was seen as developing organically, emerging from the community first, before university researchers approached them. “I think that almost all of the projects [were] always started by some people in the community really figuring out the intervention that needed to be addressed and figuring out how to best serve this community and use it as a model…I think what they are speaking to is the organic nature of community building. And community building then transcends the very idea of community organizing which a lot of people do. You can go into communities. You can organize communities…These major organizations do that and that’s fine but they’re not community building. They are organizing around particular issues and that’s fine but that’s not what we believe will make the difference ultimately in terms of being transformative in the context of community” (PRCC).

The Chinatown partnership, not aimed at an intervention per se, and not yet being at their policy action phase, found the intervention construct to be difficult to understand at first. After more dialogue, however, the group felt that “reflecting community understanding, fitting with cultural knowledge, norms, and practices and informed by local institutions” was particularly relevant. The concept, appropriate research design, prompted reflection on fundamental power dynamics within a research enterprise. “I think what it raises for me when we say appropriate research design, it comes from a perspective that it’s like community-based stuff is trying to fit into science. So there has to be an acknowledgement of the power dynamic…. So the power dynamic is that we do want to be bi-directional, we want to be like have an appropriate equal but we just have to recognize that maybe, as one of the contexts, is that basically it’s trying to provide legitimacy for what’s happening in the community through science or research.

The importance of vocabulary used in the model was discussed directly. Many recommended finding words that were different from those currently in the model. NCC participants suggested word changes to replace explanatory model and bidirectional translation/implementation, however no specific new phrases were provided; (these phrases were subsequently replaced by more community appropriate language for the revised model, with the original phrases moved to a new list created below this oval). We also renamed the dimension, intervention and research, to recognize the spectrum of research methodologies, including assessment, epidemiology or policy research that can also employ CBPR approaches.

As a critically important construct to add to this section, we heard statements about partnership effectiveness developing over time, or partnership synergy, defined as a proximal outcome of effective collaborative processes (Weiss, Anderson, & Lasker, 2002). As one community member stated, “And then you go through the process of developing partners to get the outcome, through the partnerships and resources; and you develop the intervention to have an outcome and that’s kind of what drives you, I think the health issue” (Tribal). In sum, the model suggests that effective group dynamics can produce partnership synergy (which we then added to the revised model, see Figure 2), as well as culturally-appropriate interventions and research designs that fit within local contexts.

Outcomes

The fourth oval, outcomes, refer to intermediate system and capacity changes, as well as more distal “health outcomes” which would be enhanced by stronger partnership synergy. While dialogue on outcomes fell naturally towards the end, it was clear that many of the outcomes were related in a dynamic process throughout the CBPR process, and linked in a feedback loop to contextual factors, and to the cross-cutting constructs of trust development; capacity; mutual learning; and power dynamics (see Table 5).

System Level changes

While the community perspectives validated the idea of system changes, such as program sustainability after a grant ends, the narratives enriched our understanding of system-level changes through ripple effects or translation beyond the initial community. This is a novel idea of a broader reach, for local CBPR projects. Many CBPR teams, however, have connections beyond the immediate community through CDC or APHA. Reflecting a dynamic systems perspective, intervention ideas that work well in one community may be translated to and re-contextualized within other communities, which may be close by or within broader networks of CBPR nationally.

Capacity Changes

Capacity outcomes have been defined as community capacity to create desired community changes through increased participation, new skills, and empowerment (Goodman, Speers, & McLeroy, 1998), or new research skills; as well as the university’s capacity to support community engaged research. However, a more nuanced perspective was captured by the Puerto Rican partnership with the community engaging in a deliberative university capacity-building process, through preparing the academic partner for future collaborative work. The idea of the academic partner gaining capacity and learning as a result of CBPR has not been well researched. The narrative began to capture these nuances, however, with the recognition that community partners can foster as researcher capacity and acculturation to community culture and life conditions.

Other community narratives spoke directly to empowerment as an outcome, beyond the power discussions within the group dynamics section of the model. Changes in capacity to more fully recognize aspects of domination and subjugation is a potentially important collective reflection capacity outcome in CBPR that is not typically captured. This awareness, combined with conscious actions to transform academic partners as related by the Puerto Rican community, is akin to Paulo Freire’s critical consciousness or conscientization (Freire, 1970).

Another expanded area of capacity was the recognition of benefits that community partners perceived, such as training related to research or encouragement to go back to school, as shown in this statement by a community partner: “You have to have education; if you play the game right, you can go all the way to change policy to have better outcomes in your native communities… You need to be at the same level to play their game and then try to turn things around to benefit your community” (Tribal).

Policy changes

The original model recognized transformed (or new) policies and practices as important outcomes leading to or sustaining health outcomes. One partnership related the importance of engaging governmental officials in order to affect policy. While policy was considered an outcome in the original model, additional discussion broadened the policy concept to include the reach of partnerships to assure change and acquisition of additional resources. This broader reach or expanded networks is suggestive of spillover effects of systems changes within a larger societal context that can still benefit the local community. Several groups talked about personal capacity development and skill development in policy advocacy as a result of participating in the partnership.

While most of the constructs were discussed within one of the four dimensions, there were four cross-cutting constructs, identified because they were discussed across two or more of the dimensions. These were: trust development; capacity; mutual learning (including through self- and collective-reflection), and power dynamics. While discussions of these concepts are presented in more depth under separate dimensions, it is helpful to briefly articulate how participants drew connections across dimensions.

Trust development, in particular, was noted as permeating and affecting all interactions and relationships in the partnership and as linking one dimension to another. While trust was explicitly named under context as part of historic mistrust vs. trust of research, the implication for current relational dynamics, agreements, and safe partnership environments was strongly stated. Trust development was said to be important in the “getting to know each other” stage, but also as operating within the “ether,” a fluid space that is dependent on the interpersonal skills of academic and partners, and the evolving processes of collective reflection.

The concept of capacity was listed twice in the original model, both as context as well as outcome, yet it was a recurring construct, with meanings intertwined. The importance of university as well as community capacity was reaffirmed, especially in discussions noting the insufficient number of researchers (and staff and students) of color who served as important bridge people for strengthening group dynamics. The deliberate nurturing of academic capacity to conduct CBPR as an outcome was also noted, as researcher acculturation to community cultural life, and important for preparing researchers for sustained or new partnered research. The ability of academics to genuinely recognize and include community knowledge and theories in etiological and intervention research was seen as key to researcher acculturation.

While mutual learning (including self and collective reflection) was originally listed under group dynamics and discussed as building a foundation of safety and reciprocity, its value was expanded as critical for the development of successful and appropriate interventions, and as an outcome itself. Finally, power was discussed throughout. Starting with context, participants acknowledged power hierarchies within university resources and scientific language, as both explicit and implicit sources of power. Given community histories of being colonized within the research enterprise, power was discussed as permeating group dynamics, i.e., in leadership and negotiations; and therefore, influencing decisions regarding interventions and research designs. Ultimately, community empowerment and transformed power relations were considered important outcomes. These cross-cutting constructs reinforce the iterative, non-linear nature of CBPR and partnership processes represented by the model.

Discussion

The multilevel, complex systems CBPR model was initially developed through an extensive literature review and academic consensus-building effort. This paper reported feedback from consultations with community partners with several important findings: (a) the model appears to have strong face validity across racial/ethnic and geographically diverse partnerships; (b) the dimensions and constructs provide useful departure points from which to discuss partnership practices within particular communities; (c) relationships among the model dimensions were supported as participants organically described the linkages and influences of one dimension with another; and (d) new or enhanced concepts were suggested that were missing from the original model. Most importantly, the discussions illustrated the model’s usefulness as a source of self- and collective reflection, and ongoing process evaluation for partners.

Across the dimensions of contexts, group dynamics, research and intervention, and outcomes, participants consistently identified with constructs salient to their experiences and provided examples of operationalization. Four constructs were seen as cutting across the model: trust development, capacity, mutual learning (including self and collective reflection), and power. For the most part, the language of the model was acceptable to the community partners, except for the dimension of research and intervention, which received mixed reviews for its technical language. As a result of these responses, we deleted the academic terms and substituted lay language in the revised model, i.e., “fits with local cultural knowledge, norms and practices,” instead of “fits with local explanatory models.”

Community partners also suggested several new concepts and expanded interpretations for a revised model; and provided an array of concrete expressions of the constructs in practice. New concepts included the contextual importance of place (or geography), the role of institutions and negative institutional policies, and the role of education as a baseline and path for capacity-building. The group dynamic’s concept of stewardship was added to discussion on power-sharing, to include the importance of shared responsibility in terms of workload, ethical accountability, and in translating research to action for the benefit of the community. The role of a bridge person who is able to bring together the different worlds of communities and academia was expanded, and identified as either community leaders and professionals, or research staff and students who share ethnic/racial identities or have other connections with the community. Building on culture, spirituality, was also declared to be important, which often plays an essential role in the lives of community members, including spirituality as a legacy of the Civil Rights Movement, and health equity as a spiritual framework that adds both meaning and endurance to the struggle.

Language was identified as an important manifestation of power hierarchies and mechanism of exclusion. Excessive use of research jargon often marginalized community participants causing frustration in the partnership process. As a proximal outcome, partnership synergy was highlighted for the creation of research and intervention designs and for leading to more intermediate system and capacity changes. For outcomes, in addition to a focus on community capacity outcomes, which are often expected from CBPR partnerships, the community representatives focused on University capacity changes, such as acculturating academics to really learn how to work with communities. Community capacities were additionally discussed as a personal benefit of skill development, for example, in research knowledge or in policy change. Finally, because of the iterative nature of the discussion and the fact that participants talked about the impact of emerging outcomes on their partnerships and even on their community contexts, we added several feedback loops from outcomes to each of the other ovals. We recognize that these feedback processes are not pre-determined, but are potentially powerful additional outcomes of CBPR.

Our findings mirror several explanatory theories that have also begun to emerge linking partnering processes to outcomes. While our community consultation occurred earlier than some of these newer studies, it is striking that elements within our model are also being validated by others. Partnership synergy in particular has been proposed as a meso-level theory that shows how group effectiveness is important for achieving the goals and tasks of the grant. (Jagosh et al., 2012; Khodyakov et al., 2013; Khodyakov et al., 2011). Trust development has also begun to emerge as a synthesizing theory that is important to nurture and develop, especially with histories of mistrust (Lucero, 2013; Lucero & Wallerstein, 2013). Finally, community participation in research steps is gaining recognition as an effective practice (Khodyakov et al., 2013; Khodyakov et al., 2011; Mercer et al., 2008) and links to the appropriateness of fit between the research and the community culture.

There were limitations to our analysis of the face validity of the model and its usefulness for evaluation and reflection for CBPR partnerships. Both time constraints and interest of the focus groups meant that not all partnerships equally reviewed each of the four dimensions of the model; some paid attention to one or two dimensions over the others. Covering all aspects of the model in a single focus group proved challenging and partnerships tended to direct the discussion to areas most salient to their needs. As seen by the data, more conversation was held on contexts and group dynamics, probably because most partnerships started with discussion from left to right. Despite the difference among focus group discussions, all groups recognized all four dimensions of the model as holistic, and highlighted the ways in which each dimension influenced the other dimensions with continual feedback loops. Rather than a limitation, however, the fact that each partnership used the model to discuss salient aspects of their work could be interpreted as a strength. It shows that the model can serve as a discussion trigger for collective reflection and evaluation of partnering practices or impacts most appropriate to that partnership at any particular time.

While the focus groups were conducted in 2009 the revised model continues to be investigated and tested in a national cross-site CBPR research project, with three partners: the Universities of New Mexico and Washington, and the National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center. This partnership received Native American Research Centers for Health funding (2009–2013) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study variability of community academic partnerships and to assess associations between partnering processes and CBPR and health outcomes. This mixed methods study design used the model’s constructs to build internet-survey instruments to measure many of the partnering and outcomes constructs, for its data collection of 294 NIH and CDC-funded research projects; and to create qualitative instruments to guide data collection for seven CBPR case studies across the country (Hicks et al., 2012; Lucero et al., submitted; Oetzel, Zhou, Duran, Pearson, Magarati, & Wallerstein, in press; Pearson et al., in press) for instruments and interview guides (see http://cpr.unm.edu/). Coupling the ongoing future analyses from the NIH cross-site research study with the community consultation reported here will continue to strengthen the model’s usefulness for partnership collective reflection and evaluation.

Research and Practice Implications and Recommendations

The findings in this paper reveal how a CBPR conceptual/logic model was assessed and used by six groups of community-based research partners from across the country. Overall, the model was viewed as a valid expression of key dimensions of collaborative participation in research. It offers diverse stakeholders an opportunity to identify and assess the complexities and challenges of maintaining authentic partnering across planned, as well as unexpected changes that occur in social and health research. The model has shown itself to be comprehensive enough to address the diversity of experiences within the complex social systems of community-engaged and participatory research. Focus groups resonated with existing model dimensions and also identified new key elements of engagement resulting in a revised model.

Each group acknowledged community/academic partnerships as a fluid experience and were able to identify how the quality of specific key elements, i.e., shared power, trust development, mutual learning, and capacity, were benchmarks of “successful’ engagement. The interpretation of these benchmarks, in turn, may depend on the context and history of the partnership, the stage of the partnership or phase of research, and the level of agreement among participants. While this could be seen as a limitation in that partners might require extensive dialogue to gain common understanding or precise definitions of terms; on the other hand, this could be seen as a strength of the model.

To be most useful as a tool for self-reflection and partnership evaluation, we recommend the model be seen as a dynamic entity that offers four core dimensions, with flexibility for individual partnerships to add constructs and assess issues that most concern them – from their own contexts, partnering practices, and desired outcomes. As partnerships employ the model in evaluation and reflection over time, collecting the range of uses and interpretations will be invaluable in its continuing refinement. Our goal in validating this model with community voices was to enhance our understanding of how CBPR partnering practices can contribute to outcomes. By doing so, we hope we’ve strengthened our collective capacity of authentic partnered research to achieve health equity.

Contributor Information

Lorenda Belone, Email: LJoe@salud.unm.edu.

Nina Wallerstein, Email: Wallerstein@salud.unm.edu.

References

- Allen MD. Telephone focus groups: Strengths, challenges, and strategies for success. Qualitative Social Work. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1177/1473325013499060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnidge EA, Baker EA, Motton F, Rose F, Fitzgerald T. A participatory method to identify root determinants of health: The heart of the matter. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2010;4(1):55–63. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnidge EK, Baker EA, Motton F, Rose F, Fitzgerald T. Exploring community health through the sustainable livelihoods framework. Health Education & Behavior. 2011;38(1):80–90. doi: 10.1177/1090198110376349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EA, Motton F. Creating understanding and action through group dialogue. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey, Bass; 2005. pp. 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Baker EA, Motton F, Barndige EK, Rose F. Collaborative data collection, interpretation, and action planning in a rural African American community: Men on the move. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods for community–based participatory research for health. 2nd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2013. pp. 435–462. [Google Scholar]

- BeIl J, Standish M. Communities and health policy: A pathway for change. Health Affairs. 2005;24(2):339–342. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belone L, Oetzel J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Tafoya G, Rae R, Thomas A. Using participatory research to address substance abuse in an American Indian community. In: Frey LR, Carragee K, editors. Communication activism. Vol. 3. New York, NY: Hampton Press; 2012. pp. 403–434. [Google Scholar]

- Belone L, Tosa J, Shendo K, Toya A, Straits K, Tafoya G, Wallerstein N. Community based participatory research (CBPR) principles and strategies for co-creating culturally-centered interventions with Native communities: A partnership between the University of New Mexico and the Pueblo of Jemez with implications for other ethnoculutral communities. In: Zane N, Leong F, Bernal G, editors. Culturally Informed Evidence Based practices. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bozlak CT, Kelley MA. Youth participation in a community campaign to pass a clean indoor air ordinance. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11(4):530–540. doi: 10.1177/1524839908330815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:325–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Salvatore A, Lee P, Liu SS, Minkler M. Popular education, participatory research, and community organizing. In: Minkler M, editor. Community organizing and community building for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Salvatore AL, Lee PT, Liu SS, Tom A, Morales A, Minkler M. Adapting to context in community-based participatory research: “Participatory starting points” in a Chinese immigrant worker community. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;51(3–4):480–491. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9565-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. Addressing racial and ethnic disparities: Lessons from the REACH 2010 communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17(2):1–5. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankwa-Mullan I, Rhee KB, Williams K, Sanchez I, Sy FS, Stinson N, Ruffin J. The science of eliminating health disparities: Summary and analysis of the NIH summit recommendations. American Journal of Public Health. 2010 Apr 1;100(Supp 1):S12–S18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta MJ. Communicating about culture and health: Theorizing culture-centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Communication Theory. 2007;17:304–328. [Google Scholar]

- English KC, Wallerstein N, Chino M, Finster CE, Rafelito A, Adeky S, Kennedy M. Intermediate outcomes of a tribal community public health infrastructure assessment. Ethnicity and Disease. 2004;14(S1):63–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S, Travers R, Guta A, McDonald S, Meagher A. Ethical dilemmas in community-based participatory research: Recommendations for institutional review boards. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;84(4):478–493. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9165-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Gaydos M, Bhatia R, Morales A, Lee PT, Liu SS, Chang C, Minkler M. Promoting health and safety in San Francisco’s Chinatown restaurants: Findings and lessons learned from a pilot observational checklist. Public Health Reports. 2011;126(Suppl 3):62–69. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Speers MA, McLeroy K. Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:258–278. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, George A, Daniel M, Frankish CJ, Herbert CP, Bowie WR, O’Neill M. Study of participatory research in health promotion: Review and recommendations for the development of participatory research in health promotion in Canada. Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Greene-Moton E, Palermo AG, Flicker S, Travers R. Trust and communication in a CBPR partnership – Spreading the “glue” and having it stick. Developing and sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: A skill-building curriculum. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.cbprcurriculum.info.

- Hicks S, Duran B, Wallerstein N, Avila M, Belone L, Lucero J, White Hat E. Evaluating community-based participatory research (CBPR) to improve community-partnered science and community health. Progress in Community Partnerships. 2012;6(3):289–311. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods for community-based participatory research for health. 2nd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, Salvatore A, Minkler M, Lopez J. Community-based participatory research: Lessons learned from the centers for children’s environmental health and disease prevention research. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113(10):1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]