ABSTRACT

Cancer immunotherapy is an attractive therapeutic option but it is currently unclear which patient may benefit from such approaches. Using the model of cervical cancer, we have demonstrated that PolyIC-driven immunogenicity strictly depends on the necroptosis regulator RIPK3 in the neoplastic cells. This proposes RIPK3 as a novel predictive marker for personalization of cancer immunotherapy

KEYWORDS: Cancer, dsRNA, Dendritic cells, Immune response, RIPK3

Abbreviations

- DC

Dendritic cell

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- RIPK3

receptor-interacting protein kinase

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

Individualized immunotherapy is a promising option to improve efficacy of cancer therapy. dsRNA such as PolyIC-derivatives are currently tested in clinical trials as vaccine adjuvants or intratumorally as immunostimulants for different solid cancers 1 (https://clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01984892). Cancer tissue consists of many cell types and PolyIC may activate immune cells within the tumor microenvironment directly. Notably, neoplastic cells may also recognize PolyIC and boost these immune responses, which may determine treatment outcome. In these cells, PolyIC is thought to act via inflammasome activation or interferon (IFN) induction.

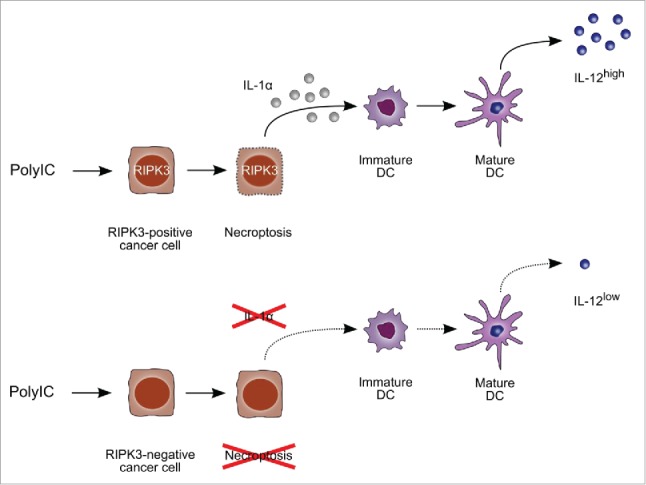

We were interested in the effects of PolyIC in cancers, in which PolyIC-mediated inflammasome activation or IFN induction is missing. Therefore, we selected a human papillomavirus (HPV)-driven cancer model, in which the viral oncoproteins abrogate these pathways 2-5 and the neoplastic cells rather support an immunosuppressive microenvironment. 6-8 Unexpectedly, we demonstrated that successful immune activation was strictly dependent on cancer cell expression of receptor-interacting protein kinase RIPK3, a key regulator of necroptosis (Fig. 1).9

Figure 1.

RIPK3-positive (upper panels) but not RIPK3-negative cancer cells (lower panels) undergo necroptosis in response to PolyIC leading to release of the alarmin IL-1α and dendritic cell activation.

A critical factor determining antitumor immunity is IL-12. lL-12 is produced by professional antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells (DC) linking innate and adaptive immunity. To test whether PolyIC can restore DC function and raise IL-12 levels in the context of cervical cancer, we used two representative cell lines, the squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) line C4-I and the adenocarcinoma line HeLa. Two protocols of DC stimulation for IL-12 production were initially compared: (i) direct stimulation of DC with PolyIC and (ii) DC stimulation with supernatants of PolyIC-treated cervical cancer cells. The result was surprising. The immunostimulatory capacity of supernatants from PolyIC-treated C4-I cells tremendously exceeded that of direct DC stimulation.9 This effect was not observed with HeLa cells (“non-responder” cell line).

We then compared the “responder” cell line C4-I with the “non-responder” HeLa cells to identify the molecular basis of PolyIC-induced immunogenicity. The most obvious difference between both cell types was PolyIC-induced cell death, which occurred only in responder but not in non-responder cells (Fig. 1).9 PolyIC-treated C4-I cells showed morphological and biochemical signs of apoptosis and also of necrosis as demonstrated by Hoechst staining, Caspase-3 activation, lactate dehydrogenase-release and propidium iodide incorporation. This indicated a mixed form of programmed apoptosis and necrosis, variously also called necroptosis. Moreover, only the responder cells released the alarmins High-Mobility-Group-Protein HMGB1 and IL-1α during cell death. The inflammasome-driven cytokine IL-1β or type I IFNs were barely produced by either of the cell lines confirming published studies. Neither pan-caspase nor caspase-1 inhibition interfering with inflammasome activation in the responders blocked cell death or subsequent DC activation. This indicated that neither apoptosis, inflammasome activation nor an intact IFN response were required for immunogenicity of the cancer cells. Moreover, HMGB1 did not elicit IL-12 production by DC. In contrast, IL-1α release from necroptotic cancer cells was necessary for DC activation, as shown in neutralization assays with IL-1 receptor antagonist or IL-1α-specific neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 1).9

Notably, C4-I cells potently expressed the necroptosis factor RIPK3,9 while HeLa cells did not.9,10 RIPK3 expression was essential for immunogenicity as demonstrated by siRNA-mediated knock-down. RIPK3 knock-down blocked cell death, release of the alarmin IL-1α and DC activation after PolyIC-treatment of C4-I cells (Fig. 1). 9 In contrast, the related factor RIPK1, which has also been implicated in necroptosis, was equally expressed in both cell lines and its knock-down did not decrease immunogenicity.9 Thus, our data clearly demonstrated that RIPK3 but not RIPK1 expression discriminates between responders and non-responders (Fig. 1).

To investigate the in vivo relevance of our finding, we studied RIPK3 expression patterns in biopsies of cervical cancer patients. We found RIPK3 expression in all tested SCCs but expression levels varied greatly. The inter-individual and intra-tumoral variation was even more pronounced in adenocarcinomas compared with SCCs. 50% of adenocarcinomas were RIPK3-negative similarly to HeLa cells.9,10 Thus, RIPK3 is individually expressed in cervical cancer.

From our data, we conclude that RIPK3 is a key determinant of immunogenicity in the cervical cancer model. RIPK3 expression decides upon cell death, alarmin release and DC activation after PolyIC treatment. So far, RIPK3 expression patterns in most cancer types remain unclear. This, however, will be interesting to investigate, since RIPK3 may determine immunogenicity also in other, non-virally induced cancers in response to dsRNA-based immunotherapies with PolyIC-derivatives, other dsRNA-based adjuvants or even dsRNA delivered by oncolytic viruses.

Given the central role of RIPK3 and the heterogeneous RIPK3 expression patterns, we propose that particularly in cancer types with disturbed inflammasome and IFN pathways, RIPK3 should be evaluated as a novel clinical marker predictive for response to dsRNA-based immunotherapies.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Glavan TM, Pavelic J. The exploitation of Toll-like receptor 3 signaling in cancer therapy. Current Pharm Des 2014; 20:6555-64; PMID:25341932; http://dx.doi.org/10201939 10.2174/1381612820666140826153347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smola-Hess S, Pfister HJ. Immune Evasion In Genital Papillomavirus Infection And Cervical Cancer: Role Of Cytokines And Chemokines In: Campo S, ed. Papillomavirus Research: From Natural History To Vaccines and Beyond; Caister Academic Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altenburg A, Baldus SE, Smola H, Pfister H, Hess S. CD40 ligand-CD40 interaction induces chemokines in cervical carcinoma cells in synergism with IFN-gamma. J Immunol 1999; 162:4140-7; PMID:10201939 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guess JC, McCance DJ. Decreased migration of Langerhans precursor-like cells in response to human keratinocytes expressing human papillomavirus type 16 E6/E7 is related to reduced macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha production. J Virol 2005; 79:14852-62; PMID:16282485; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14852-14862.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karim R, Meyers C, Backendorf C, Ludigs K, Offringa R, van Ommen GJ, Melief CJ, van der Burg SH, Boer JM. Human papillomavirus deregulates the response of a cellular network comprising of chemotactic and proinflammatory genes. PloS One 2011; 6:e17848; PMID:21423754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hess S, Smola H, Sandaradura De Silva U, Hadaschik D, Kube D, Baldus SE, Flucke U, Pfister H. Loss of IL-6 receptor expression in cervical carcinoma cells inhibits autocrine IL-6 stimulation: Abrogation of constitutive monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production. J Immunol 2000; 165:1939-48; PMID:10925276; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pahne-Zeppenfeld J, Schroer N, Walch-Ruckheim B, Oldak M, Gorter A, Hegde S, Smola S. Cervical cancer cell-derived interleukin-6 impairs CCR7-dependent migration of MMP-9-expressing dendritic cells. Int J Cancer 2014; 134:2061-73; PMID:24136650; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.28549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroer N, Pahne J, Walch B, Wickenhauser C, Smola S. Molecular Pathobiology of Human Cervical High-Grade Lesions: Paracrine STAT3 Activation in Tumor-Instructed Myeloid Cells Drives Local MMP-9 Expression. Cancer Res 2011; 71:87-97; PMID:21199798; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt SV, Seibert S, Walch-Ruckheim B, Vicinus B, Kamionka EM, Pahne-Zeppenfeld J, Solomayer EF, Kim YJ, Bohle RM, Smola S. RIPK3 expression in cervical cancer cells is required for PolyIC-induced necroptosis, IL-1alpha release, and efficient paracrine dendritic cell activation. Oncotarget 2015; 6:8635-47; PMID:25888634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 2012; 148:213-27; PMID:22265413; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]