Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with increase in brain of the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), which is over-expressed in activated microglia and reactive astrocytes. Measuring the density of TSPO with PET typically requires absolute quantitation with arterial blood sampling, because a reference region devoid of TSPO does not exist in brain. We sought to determine whether a simple ratio method could substitute for absolute quantitation of binding with 11C-PBR28, a second generation radioligand for TSPO.

Methods

11C-PBR28 PET imaging was performed in 21 healthy controls, 11 individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and 25 AD patients. Group differences in 11C-PBR28 binding were compared using two methods. First, the “gold standard” method of calculating total distribution volume (VT), using the two-tissue compartmental model with the arterial input function, corrected for plasma free fraction of radiotracer (fP). Second, a ratio of brain uptake in target regions to that in cerebellum—i.e., standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR).

Results

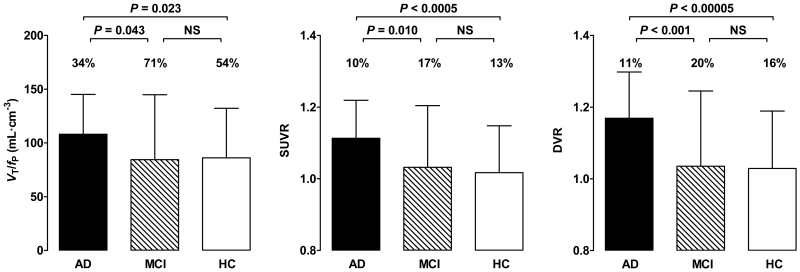

Using absolute quantitation, we confirmed that TSPO binding (VT/fP): 1) was greater in AD patients than in healthy controls in expected temporo-parietal regions, and 2) was not significantly different among the three groups in cerebellum. Using the cerebellum as a pseudo-reference region, the SUVR method detected greater binding in AD patients than controls in the same regions as absolute quantification and in one additional region, suggesting SUVR may have greater sensitivity. Coefficients of variation of SUVR measurements were about two-thirds lower than those of absolute quantification, and the resulting statistical significance was much higher for SUVR when comparing AD and healthy controls (e.g. P < 0.0005 for SUVR vs. P = 0.023 for VT/fP in combined middle and inferior temporal cortex).

Conclusion

To measure TSPO density in AD and control subjects, a simple ratio method SUVR can substitute for, and may even be more sensitive than, absolute quantitation. The SUVR method is expected to improve subject tolerability by allowing shorter scan time and not requiring arterial catheterization. In addition, this ratio method allows smaller sample sizes for comparable statistical significance because of the relatively low variability of the ratio values.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, neuroinflammation, 11C-PBR28, positron emission tomography, ratio method

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with neuroinflammation characterized by activated microglia and reactive astrocytes. Because these reactive neuroimmune cells overexpress the translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO), TSPO density has been used as a biomarker for neuroinflammation in AD and other neurological diseases (1). We recently found that TSPO binding was greater in AD patients than in age-matched controls or patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who had a positive amyloid scan (2). That is, increased TSPO binding appeared to mark, and might play a pathophysiological role in, the transition from MCI to AD.

A major barrier to expanding studies that use TSPO imaging to assess the potential role of inflammation in AD is that PET measurements of TSPO density typically require ‘absolute’ quantitation relative to the concentration of radioligand in arterial blood. This measurement of plasma concentrations adds error to the final values, requires significant equipment and expertise, and entails arterial catheterization of the subject. A ‘relative’ method of measurement (e.g., one brain region compared to another) would be expected to have smaller variability than an absolute value, in part because of cancellation of global scale changes or errors in measurement of plasma concentrations. However, relative measurement requires either a reference or a pseudo-reference region. Unfortunately, a true reference region (i.e., devoid of TSPO) does not exist in brain, as TSPO is present in gray matter, white matter, vessel walls, and even choroid plexus (3, 4). A pseudo-reference region would contain TSPO but not differ between comparison groups. Such a region could, for example, be used to compare the ratio of target to pseudo-reference region in patients vs. controls. However, this approach requires that prior studies using absolute quantitation confirmed that the pseudo-reference region does not significantly differ between patients and controls. To date, no study has identified or proved that a pseudo-reference region exists for second generation TSPO imaging in AD, including white matter.

Using absolute quantitation, we previously found that TSPO binding in cerebellum, measured with 11C-PBR28, did not differ between AD patients and either healthy controls or MCI subjects (2). This finding is consistent with the cerebellum of AD patients being relatively spared of pathology, including inflammation (5-7), and suggests that cerebellum could be used as a pseudo-reference region as an alternative to absolute quantification.

This study sought to determine whether the method of absolute quantitation that requires arterial blood sampling could be substituted with a simple method that uses only the ratio of brain radioactivity in a target region compared to that in cerebellum. We recruited a total of 15 more subjects than in our previous report (2) and then measured TSPO binding in 25 AD patients, 21 healthy controls, and 11 patients with MCI. We compared two methods of analysis, absolute quantitation of receptor binding, which requires an arterial input function, and relative quantitation of receptor binding, which requires only PET images and was calculated as the ratio of brain uptake in target regions compared to that in cerebellum (i.e., standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR)).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subjects included 21 healthy controls (15M, 6F, mean age = 55.1 ± 15.3 years), 11 MCI patients (7M, 4F, mean age = 72.2 ± 9.3 years), and 25 AD patients (11M, 14F, mean age = 63.0 ± 8.3 years). All patients were “amyloid-positive” on PET imaging with 11C-Pittsburg Compound B (PIB) based on criteria used in our earlier study (2). AD patients met updated criteria for probable AD dementia with evidence of AD pathophysiological process (8), and MCI patients met updated criteria for MCI due to high or intermediate likelihood of developing AD (9). Some subjects were included in our previously published study (2). Binding affinity status (high, mixed, or low) was determined using leukocyte binding assay as previously described (2, 10), and low affinity binders were excluded from the study. There were 7 high-affinity binders (HABs) and 14 middle affinity binders (MABs) among healthy control subjects, 5 HABs and 6 MABs among MCI patients, and 11 HABs and 14 MABs among AD patients. Both radioligand preparation and acquisition and processing of 11C-PBR28 PET and magnetic resonance images are described in the Supplemental Methods. PET images were not corrected for partial volume effects (PVE).

This study was approved by the Combined Neuroscience Institutional Review Board of the NIH Intramural Research Program. All subjects or their surrogate provided written informed consent to participate.

Estimation of Binding Values

All kinetic analyses were performed with the PKIN module in Pmod 3.1 (PMOD Technologies Ltd.). The consensus nomenclature of reversible binding radioligands was followed (11).

Metabolite-corrected plasma input function and whole blood radioactivity were fitted to tri-exponential function. Time delay from the radial artery to brain was calculated with the whole blood radioactivity curve and whole gray matter TAC. Using the two-tissue compartmental model, a model curve was fitted to regional TACs with metabolite-corrected input function as described previously (12). Finally, VT was calculated using the rate constants (K1, k2, k3, and k4) estimated from this model and corrected for plasma free fraction of radioligand (fP).

For a non-invasive measure of 11C-PBR28 binding, we created time-averaged images from 30-minute intervals of scan data (10 - 40, 20 - 50, 30 - 60, 40 - 70, 50 - 80, and 60 - 90 minutes) and converted the measured activity to SUV by multiplying subject body weight and dividing by injected activity. Regional SUV values were measured by overlaying the volume-of-interest (VOI) mask using the same regions-of-interest studied in our prior report (2), and regional SUVR values were calculated by dividing SUV value of each region by cerebellar SUV value. We sought to determine which time points best provided SUVR values, similar to the determination made for PIB by Price and colleagues (13). Unlike 11C-PIB, which shows stable ratio of radioactivity in cerebellum to plasma in late time points of the PET scan (13), for 11C-PBR28 this ratio increased until the end of the scan without plateauing. Therefore, to acquire an optimal time interval for SUVR, we performed a linear regression analysis between VT/fP values calculated from the entire 90 minutes scan and SUVR values calculated from sequential 30-minute time intervals of the image data from the combined middle and inferior temporal cortex (Supplemental Fig 1). Because the best correlation was achieved with data from 60 to 90 minutes (r = 0.35, P = 0.008), we used 60 to 90 minutes as the time interval for obtaining SUVR values for the remainder of the analysis. We also compared group binding using distribution volume ratio (DVR) by dividing the VT of each target region by VT of the cerebellar pseudo-reference region.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 11.5 (SPSS Inc.) was used for the statistical analysis. Statistical correction for TSPO genotype was performed according to previously published methods (2). For VT/fP, SUVR, and DVR, TSPO genotype was used as a fixed factor to correct for affinity differences caused by the rs6971 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). For SUVR, statistical analysis was also performed without TSPO genotype correction. Benjamini-Hochberg’s false discovery rate (FDR) with threshold P-value = 0.05 was used to correct for region-wise multiple comparisons (14). Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons of each between-group comparison. Variability of binding values was defined as coefficient of variation (%COV) = standard deviation / mean × 100%. For correlative analyses, correlations were first run between the individual outcome measures and TSPO genotype. Standardized residuals were then plotted against each other. To determine if both VT/fP and SUVR values correlate with clinical severity of AD, we performed correlative analysis with Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) – sum-of-boxes scores as independent variable and 11C-PBR28 binding values in combined middle and inferior temporal cortex as dependent variables.

RESULTS

We used cerebellar gray matter segmented by FreeSurfer to measure uptake in the pseudo-reference tissue. The mean volume of the cerebellar gray matter of healthy controls was slightly greater than that of MCI and AD patients (HC: 96.5 ± 12.0 cm3, MCI: 95.8 ± 9.4 cm3 and AD: 91.3 ± 9.8 cm3). However, no statistically significant difference was observed in cerebellar gray matter volume between the three groups, either with or without correction for age.

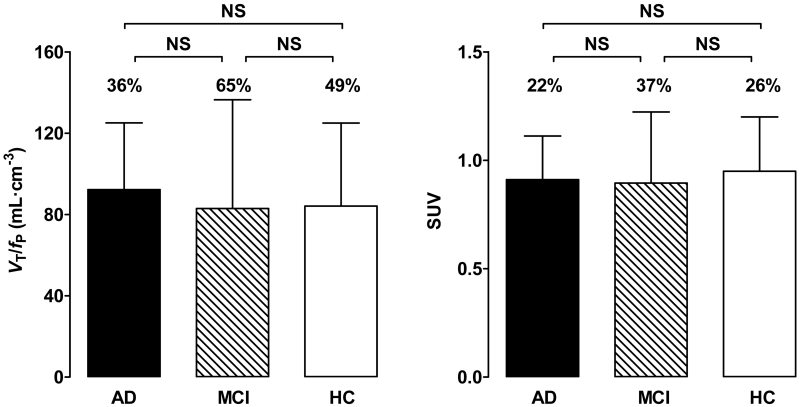

No differences in VT values were observed between the groups (Supplemental Table 1). In contrast, and consistent with results from our earlier study (2), AD patients showed greater VT/fP values than controls in the inferior parietal, combined middle and inferior temporal, and entorhinal cortices (P < 0.05; Table 1, Fig 1, and Supplemental Table 1). AD patients showed greater VT/fP values than MCI patients in the entorhinal and combined middle and inferior temporal cortices. All these regions survived correction for multiple comparisons. Cerebellar VT/fP and SUV values did not differ between controls, MCI patients, and AD patients (P > 0.05; Table 1 and Fig 2).

TABLE 1.

Effect of quantification method on level of statistical significance in detecting differences in 11C-PBR28 binding

|

P-value (AD vs. HC) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| VT/fP | SUVR | DVR | |

| Inferior parietal | 0.028 | < 0.0005 | < 0.00005 |

| Middle & inferior temporal | 0.023 | < 0.0005 | < 0.00005 |

| Precuneus | NS | 0.048* | 0.006 |

| Entorhinal | 0.048 | 0.009 | 0.001 |

| Parahippocampal | NS | 0.006 | 0.009 |

AD = Alzheimer’s disease; HC = healthy control; VT/fP = total distribution volume/free fraction of radioligand; SUVR = standardized uptake value ratio; DVR = distribution volume ratio; NS = not significant. P-values were derived from univariate ANOVA using diagnosis and TSPO genotype as fixed factors.

Region did not survive region-wise correction for multiple comparisons.

FIGURE 1.

In the combined middle and inferior temporal cortex, total distribution volume corrected for free fraction of radioligand (VT/fP), standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR), and distribution volume ratio (DVR) values were greater for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients than for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients or controls. Error bars denote mean ± SD. The SD bars have similar heights for VT/fP and SUVR due to different scales on the two y-axes. The coefficient of variation of VT/fP was three to four times greater than that for SUVR and DVR, as shown by coefficient of variation (%COV) values above the SD bars.

FIGURE 2.

In the cerebellum, 11C-PBR28 binding did not differ between controls and patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer’s disease (AD). 11C-PBR28 binding values in total distribution volume corrected for free fraction of radioligand (VT/fP) and standardized uptake value (SUV) are shown. Error bars denote mean ± SD. Coefficient of variation (%COV) values are shown above the vertical bars.

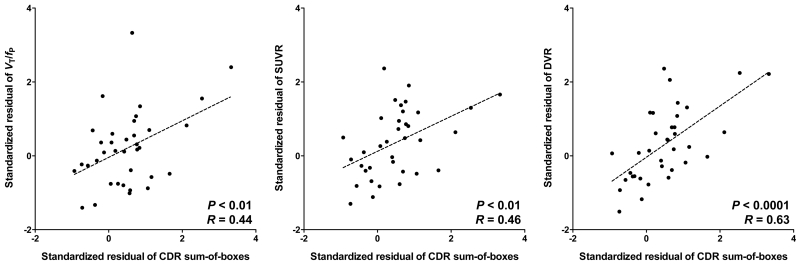

SUVR values for 11C-PBR28 were greater in AD patients than controls in the inferior parietal, combined middle and inferior temporal cortices, precuneus, entorhinal, and parahippocampal cortices (Table 1 and Fig 1). With the exception of the precuneus, these regions survived correction for multiple comparisons. The SUVR values of the combined middle and inferior temporal cortex were greater in AD patients than MCI patients and survived correction for multiple comparisons. Both VT/fP and SUVR values in combined middle and inferior temporal cortex were positively correlated with CDR sum-of-boxes scores (P < 0.01; Fig 3).

FIGURE 3.

Correlation between the binding values and the severity of cognitive impairment measured by the sum-of-boxes of clinical dementia rating (CDR) score.

Total volume of distribution corrected for plasma free fraction (VT/fP), standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR), and distribution volume ratio (DVR) of combined middle and inferior temporal cortex similarly correlated with the severity of cognitive impairment. Non-invasive ratio method did not deteriorate correlation with clinical severity.

The variability of SUVR values (%COV) was much lower than that of VT/fP values in every region and every diagnostic group (Table 2). Also, within the same TSPO genotype groups, the variability of SUVR values was much lower than that of VT/fP values (%COV of SUVR: HAB 1 - 9%, MAB 4 - 13% vs. %COV of VT/fP: HAB 13 - 27%, MAB 16 - 36%).

TABLE 2.

Effect of quantification method on variability of 11C-PBR28 binding values

| Coefficient of variation (%COV) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD |

MCI |

HC |

|||||||

| VT/fP | SUVR | DVR | VT/fP | SUVR | DVR | VT/fP | SUVR | DVR | |

| Inferior parietal | 34.5 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 70.0 | 18.0 | 19.3 | 53.4 | 14.2 | 15.2 |

| Middle & inferior temporal | 34.3 | 9.5 | 11.0 | 71.4 | 16.7 | 20.3 | 53.5 | 12.9 | 15.5 |

AD = Alzheimer’s disease; HC = healthy control; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; VT/fP = total distribution volume/free fraction of radioligand; SUVR = standardized uptake value ratio; DVR = distribution volume ratio

Data are presented as %COV (= standard deviation / mean × 100%) with 11C-PBR28 binding values corrected for TSPO genotype.

DVR values were greater in patients with AD than controls in inferior parietal lobule, combined middle and inferior temporal cortex, precuneus, hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and parahippocampal gyrus (P < 0.01). DVR values were greater in AD patients than MCI patients in inferior parietal lobule, middle and inferior temporal cortex, occipital cortex, entorhinal cortex, and parahippocampal gyrus (P < 0.04) (Supplemental Table 1). Variability was similar for both SUVR and DVR values after genotype correction (coefficient of variation = 7 - 21% vs. 8 - 25%).

SUVR values for 11C-PBR28 were greater in AD patients than controls even without genotype correction in the inferior parietal (P = 0.002) and combined middle and inferior temporal cortices (P = 0.003). However, the statistical significance was greater (P < 0.0005 for two regions above), and two more regions (entorhinal and parahippocampal cortices) became significant, after correcting for TSPO genotype. Paradoxically, mean SUVR values in HABs were consistently lower than those in MABs in all diagnostic groups and in all regions (mean SUVR values of combined middle and inferior temporal cortex (HAB vs. MAB): 0.98 vs. 1.05 in HC, 0.98 vs. 1.10 in MCI, and 1.08 vs. 1.15 in AD; Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental Fig 2).

DISCUSSION

This study found that simple ratio method (SUVR) can substitute for, and may even be more sensitive than, absolute quantitation for 11C-PBR28 PET. Therefore, this ratio method may be promising for the clinical application of 11C-PBR28 PET to study AD. One may expect the ratio method to provide results independent of TSPO genotype because affinity status is the same in both target regions and cerebellum. However, because genotype differences affect specific binding and not nonspecific binding, this ratio method should not completely remove the effect of TSPO genotype on total binding values. Therefore, TSPO genotype correction is still recommended.

The major limitation shared by all tested second-generation TSPO radioligands is differential affinity for the target protein caused by the rs6971 (Ala147Thr) SNP in exon 4 of the TSPO gene (15). Individuals without the SNP demonstrate expected affinity of radioligand for TSPO (high affinity binding). In the case of 11C-PBR28, the presence of one copy of this SNP reduces specific TSPO binding by > 40% (mixed affinity binding); those homozygous for the SNP show no discernible binding at all (low affinity binding) (10). Therefore, the gold standard method of quantification for second-generation TSPO radioligands—calculating the total distribution volume (VT) using arterial input function (12)—requires correction for affinity status to avoid underestimating TSPO density in SNP carriers. Affinity status must be determined by genetic analysis or in vivo binding assay (10, 15).

However, even within the same affinity group, significant overlap in binding values exists (10, 16), suggesting that factors other than genotype contribute to this variability (10, 17, 18). Altered TSPO expression in response to external stimuli (for instance, stress) as well as normal physiological changes may partly explain this individual variability (19, 20); it should also be noted that, even in the same subject, the contribution of these factors may change between scans. These factors may explain the low test-retest reproducibility of the TSPO radioligands 11C-(R)-PK11195 and 11C-DPA713 using traditional analytic methods (20, 21). In addition, the two-tissue compartmental model requires arterial catheterization to measure the concentration of parent radioligand in plasma. In addition to being invasive, arterial sampling adds a potential source of error that may increase PET data variability. The plasma free fraction may also contribute to variability in clinical PET studies. Therefore, a target-to-reference ratio approach may be preferable to absolute quantification with compartmental modeling, both for eliminating individual variation of physiologic TSPO expression and avoiding errors in measuring plasma concentration of radioligand. Our ratio approach appears to at least partly reduce the variability caused by differences in TSPO genotype as well. In the present study, the %COV of VT/fP was higher than 30% in all regions. This high variability requires relatively large sample sizes to detect statistically significant differences between groups. However, the variability of the SUVR was much lower (less than 22%), and we expect this ratio method to increase statistical power to detect differences in TSPO binding in clinical studies of AD.

Errors in measuring the free fraction of radioligand may also contribute to high variability in clinical PET studies. Because only free radioligand enters the brain, correcting VT for fP should theoretically increase the accuracy of PET measurement of receptor density. However, correcting for fP may introduce noise, thereby reducing precision. In our study, we found no difference in %COV between VT and VT/fP values after genotype correction (36 - 74% vs. 34 - 71%). Using VT/fP thus did not reduce precision, suggesting that the theoretically more accurate VT/fP should be used for absolute measurement of 11C-PBR28 binding.

For a ratio method to be clinically useful in PET studies, the reference region should be relatively unaffected by disease pathology in terms of the density of the target protein. Although diffuse amyloid plaques with surrounding microglia can be found in the cerebellum in advanced AD, the morphology of the cerebellar microglia differs from that of typical activated microglia in neocortex, and the cerebellum is relatively spared from neurodegeneration (5-7). Therefore, we can reasonably assume that pathological increases in TSPO are much lower in cerebellum than in cortical gray matter regions most affected by AD, and that the cerebellum can serve as the best reference region in AD (22). This argument is supported by the similar values observed for VT/fP and SUV in cerebellum among the healthy controls and MCI and AD patients in this and in our previous study (2).

When using 11C-PBR28, both DVR and SUVR discriminate AD patients from MCI patients and controls. Although the DVR method has the advantage of using the full kinetics of the radioligand, SUVR is more practical because it does not require arterial catheterization and allows for shorter scan time.

An earlier study using the second-generation TSPO radioligand 11C-DAA1106 found greater binding in AD patients than controls in several regions, including cerebellum (23). In that study, cerebellar binding potential (BPND) was 14% greater in AD patients than in controls (10 AD patients vs. 10 controls). In our larger study (25 AD patients vs. 21 controls) we found no difference in binding (using VT/fP) in cerebellum. This discrepancy could be due to several factors, including the outcome measure used and the number and characteristics of the study subjects. However, the difference in the TSPO radioligand used could also be a factor. Therefore, studies using TSPO radioligands other than 11C-PBR28 should compare cerebellar binding using absolute values (e.g., VT/fP) between patient and control groups before using this SUVR method.

Our approach in this study was similar to that of Coughlin and colleagues, who showed that normalizing the VT values of regions for 11C-DPA713 to that of total gray matter lowered variability and improved test-retest reproducibility (20). This normalization also removed the effect of TSPO genotype differences. However, using global gray matter as the reference region means that binding in the target region is represented in both the numerator and denominator. Therefore, this approach may underestimate binding in target regions, particularly relatively preserved areas in AD, and may produce unexpected results of decreased binding in those regions in AD patients.

Unlike the gray matter normalization by Coughlin and colleagues, SUVR with cerebellar pseudo-reference region did not completely ameliorate the TSPO genotype effect as larger differences between AD patients and controls were detected after correcting 11C-PBR28 binding values for affinity status. Therefore, we recommend genotype correction when using the SUVR method. In this study, TSPO genotype had a paradoxical effect on the ratio method of analysis, resulting in MABs having larger SUVR values than HABs. We are not certain if this unexpected finding represents a true result or not. Additional studies with larger sample sizes are needed to clarify the significance of this finding.

One of the most notable results of this study is clear replication of our previous findings. In our earlier study (2), we found that the AD patients showed greater VT/fP values in the inferior parietal, entorhinal, and combined middle and inferior temporal cortices than controls when using PET data not corrected for PVE. By including 15 additional subjects (42 subjects in the previous vs. 57 in the current study), we found greater 11C-PBR28 binding in AD patients in the same regions. Moreover, by using the SUVR method we found that AD patients showed greater a larger number of regions, with similar distribution to that seen in our previously reported results using 11C-PBR28 with two-tissue compartmental model and PVE-corrected data. Using SUVR values did not reduce the correlation between clinical severity and 11C-PBR28 binding seen using VT/fP. Although we did not include PVE correction in this study, we would expect to see even larger differences between AD patients and controls.

Because MCI patients with amyloid-positivity on PET are at high risk for developing dementia due to AD (24), the increased neuroinflammation observed with 11C-PBR28 PET may be a marker for conversion to clinical AD (2). We hope this SUVR method for 11C-PBR28 PET could prove useful for testing anti-inflammatory agents in AD (25).

CONCLUSION

A simple ratio method (SUVR) can substitute for, and may even be more sensitive than, absolute quantitation for detecting regions with increased binding to TSPO in AD. This method reduces variability and has the advantages of not requiring arterial sampling and allowing for shorter scan time. TSPO genotype correction was still required to increase sensitivity. This method is expected to improve subject tolerability for 11C-PBR28 PET studies in AD, particularly longitudinal studies, and increase the power necessary to detect group differences. The method also needs to be replicated in larger samples of AD patients before it can be widely used. For other diseases, application of this method will first require validation with gold standard methods of quantification that binding in cerebellum is not affected by the disease itself.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was funded in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (IRP-NIMH-NIH), the Foundation for the NIH Biomarkers Consortium, and a fellowship award from the American Academy of Neurology Foundation to William Kreisl, under clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00613119 (protocol # 08-M-0066). Ioline Henter provided excellent editorial assistance.

Footnotes

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen MK, Guilarte TR. Translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO): molecular sensor of brain injury and repair. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreisl WC, Lyoo CH, McGwier M, et al. In vivo radioligand binding to translocator protein correlates with severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2013;136:2228–2238. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen DR, Guo Q, Kalk NJ, et al. Determination of [(11)C]PBR28 binding potential in vivo: a first human TSPO blocking study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:989–994. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turkheimer FE, Edison P, Pavese N, et al. Reference and target region modeling of [11C]-(R)-PK11195 brain studies. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:158–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattiace LA, Davies P, Yen SH, Dickson DW. Microglia in cerebellar plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;80:493–498. doi: 10.1007/BF00294609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood PL. The Cerebellum in AD. In: Wood PL, editor. Neuroinflammation. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 2003. pp. 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreisl WC, Jenko KJ, Hines CS, et al. A genetic polymorphism for translocator protein 18 kDa affects both in vitro and in vivo radioligand binding in human brain to this putative biomarker of neuroinflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:53–58. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujita M, Imaizumi M, Zoghbi SS, et al. Kinetic analysis in healthy humans of a novel positron emission tomography radioligand to image the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor, a potential biomarker for inflammation. Neuroimage. 2008;40:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price JC, Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, et al. Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh Compound-B. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1528–1547. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen DR, Yeo AJ, Gunn RN, et al. An 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) polymorphism explains differences in binding affinity of the PET radioligand PBR28. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1–5. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizrahi R, Rusjan PM, Kennedy J, et al. Translocator protein (18 kDa) polymorphism (rs6971) explains in-vivo brain binding affinity of the PET radioligand [18F]-FEPPA. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:968–972. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo Q, Owen DR, Rabiner EA, Turkheimer FE, Gunn RN. Identifying improved TSPO PET imaging probes through biomathematics: the impact of multiple TSPO binding sites in vivo. Neuroimage. 2012;60:902–910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen DR, Gunn RN, Rabiner EA, et al. Mixed-affinity binding in humans with 18-kDa translocator protein ligands. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:24–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.079459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavish M, Bachman I, Shoukrun R, et al. Enigma of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:629–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Ma S, et al. Regional brain distribution of translocator protein using [11C]DPA-713 PET in individuals infected with HIV. J Neurovirol. 2014;20:219–232. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jucaite A, Cselenyi Z, Arvidsson A, et al. Kinetic analysis and test-retest variability of the radioligand [11C](R)-PK11195 binding to TSPO in the human brain - a PET study in control subjects. EJNMMI Res. 2012;2:15. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kropholler MA, Boellaard R, van Berckel BN, et al. Evaluation of reference regions for (R)-[11C]PK11195 studies in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1965–1974. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasuno F, Ota M, Kosaka J, et al. Increased binding of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor in Alzheimer’s disease measured by positron emission tomography with [11C]DAA1106. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okello A, Edison P, Archer HA, et al. Microglial activation and amyloid deposition in mild cognitive impairment: a PET study. Neurology. 2009;72:56–62. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338622.27876.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.in t’Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1515–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.