Significance

Progesterone possesses an essential role in regulating female fertility, with prominent actions throughout the female reproductive axis. The neuroendocrine actions of progesterone have been viewed as critical for the control of the female reproductive cycle. This basic principle has been reinforced by in vivo experimental paradigms, using hormone replacement as well as pharmacologic and genetic disruption of the progesterone receptor (PGR). Phenotypic characterization of Pgr null rats strengthens roles for progesterone in the regulation of female fertility, but not roles for progesterone as an essential determinant of female reproductive cyclicity, challenging an elemental principle of mammalian reproductive biology. Such findings demonstrate the benefits of genome editing in expanding available animal models for physiologic investigation.

Keywords: progesterone, rat, reproductive cycles, PGR

Abstract

The progesterone receptor (PGR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor with key roles in the regulation of female fertility. Much has been learned of the actions of PGR signaling through the use of pharmacologic inhibitors and genetic manipulation, using mouse mutagenesis. Characterization of rats with a null mutation at the Pgr locus has forced a reexamination of the role of progesterone in the regulation of the female reproductive cycle. We generated two Pgr mutant rat models, using genome editing. In both cases, deletions yielded a null mutation resulting from a nonsense frame-shift and the emergence of a stop codon. Similar to Pgr null mice, Pgr null rats were infertile because of deficits in sexual behavior, ovulation, and uterine endometrial differentiation. However, in contrast to the reported phenotype of female mice with disruptions in Pgr signaling, Pgr null female rats exhibit robust estrous cycles. Cyclic changes in vaginal cytology, uterine histology, serum hormone levels, and wheel running activity were evident in Pgr null female rats, similar to wild-type controls. Furthermore, exogenous progesterone treatment inhibited estrous cycles in wild-type female rats but not in Pgr-null female rats. As previously reported, pharmacologic antagonism supports a role for PGR signaling in the regulation of the ovulatory gonadotropin surge, a result at variance with experimentation using genetic ablation of PGR signaling. To conclude, our findings in the Pgr null rat challenge current assumptions and prompt a reevaluation of the hormonal control of reproductive cyclicity.

The fundamental elements regulating the female reproductive cycle have been universally accepted for decades and include a hierarchy of control involving the hypothalamic/anterior pituitary/ovarian axis (1,2). The hypothalamus, through its secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, drives anterior pituitary production of gonadotropins [luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)], which act on the ovaries to promote follicle development, ovulation, formation of the corpus luteum, and secretion of sex steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone. These two sex steroid hormones possess well-established actions on the female reproductive tract. At the core of the female reproductive cycle is a balance of sex steroid hormone negative and positive feedback regulation of gonadotropin secretion. Both estrogen and progesterone signaling pathways have been implicated in feedback control of gonadotropins and regulation of the female reproductive cycle (3–5). These concepts have been reinforced through phenotypic examination of mice possessing null mutations at either Esr1 or Pgr loci (6–8), and through the use of pharmacologic inhibitors of estrogen and progesterone signaling. Esr1 and Pgr encode the estrogen receptor 1 (also referred to as ER alpha) and progesterone receptor, respectively. These two nuclear receptors mediate many of the actions of estrogen and progesterone on the female reproductive system (9–11).

Historically, the rat represented the model organism for investigations on mammalian reproduction, including the regulation of female reproductive cyclicity (12–15). The advent of gene manipulation strategies in the mouse largely supplanted the rat, and over the last few decades, our understanding of mammalian reproduction has been greatly influenced by mouse mutagenesis experimentation (16). Development of genome editing strategies has decreased the dependence on the mouse and has created opportunities for investigating the regulation of mammalian reproduction in other animal model systems, including the rat. Analysis of rats with an ESR1 deficiency has further strengthened the importance of estrogen and ESR1 in regulating female reproductive cyclicity (17).

Here, using genome-editing strategies to produce Pgr null rats, we show that, as expected, progesterone signaling through the progesterone receptor (PGR) mediates progesterone action on the reproductive axis, including negative feedback regulation; however, PGR and progesterone signaling are not essential for female reproductive cyclicity. These results challenge a basic tenet of mammalian reproductive biology and force a reevaluation of the role of progesterone in the regulation of the female reproductive cycle.

Results

Targeted Disruption of the Rat Pgr Gene.

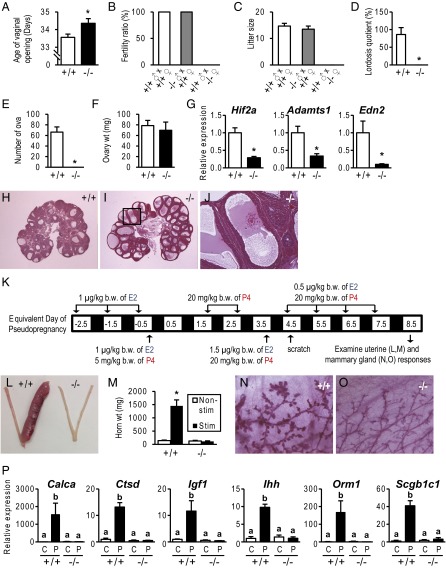

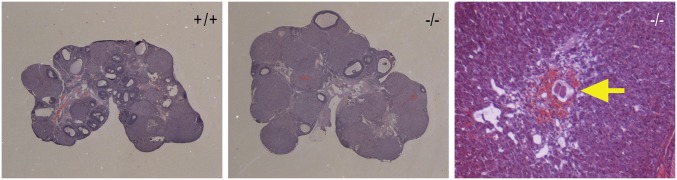

Zinc finger nuclease mediated disruption of the Pgr locus in the rat (136-bp deletion within exon 1, PgrΔ136E1; Fig. S1) yielded a nucleotide frameshift and resulted in a premature stop codon and absence of detectable PGR protein in homozygotes, resulting in a null mutation and leading to confirmation of many of the hallmarks of progesterone action, including female infertility (Fig. 1 and Figs. S1–S3). PgrΔ136E1 null female rats exhibited failures in ovulation; ovulatory responses to exogenous gonadotropins; uterine responses to progesterone, including decidualization and induction of progesterone-dependent gene expression; hormone-dependent sexual behavior; and mammary gland branching morphogenesis (Fig. 1, Fig. S3, and Movie S1). A distinctive feature of ovaries from PgrΔ136E1 null females was the presence of oocytes trapped in unruptured follicles (Fig. 1J and Fig. S3). PgrΔ136E1 null male rats were fertile. These facets of the PgrΔ136E1 null female and male rat reproductive phenotypes are consistent with previous observations in the mouse (7, 18).

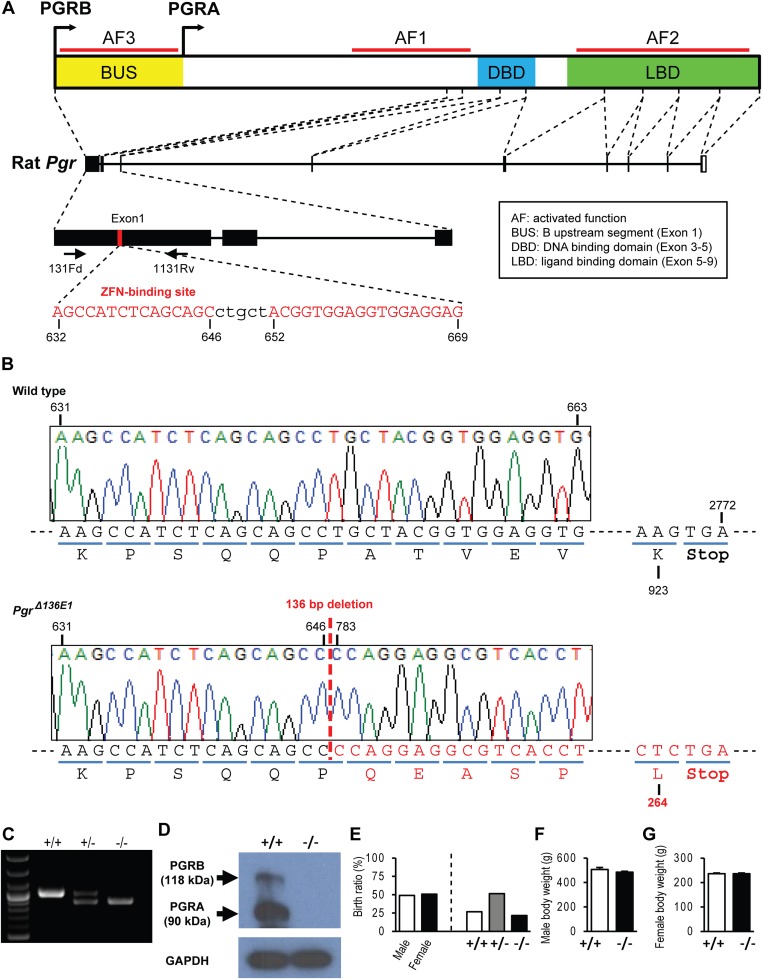

Fig. S1.

Zinc finger nuclease targeting of exon 1 within the rat Pgr locus. (A) Schematic representation of the rat Pgr gene and the zinc finger nuclease target site within exon 1 (NC_005107.3). (B) DNA sequence analysis showing a 136-bp deletion within the Pgr locus, resulting in a deletion within exon 1 (Δ136E1; PgrΔ136E1), leading to a premature stop codon and a null mutation. (C) Offspring were backcrossed to wild-type rats, and heterozygous mutant rats were intercrossed to generate homozygous mutants. Wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and null (−/−) mutations were detected by PCR. (D) Western blot analysis of PGRA and PGRB protein species in wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null uterine tissues. Note that PGR proteins were not detected in uterine tissues of PgrΔ136E1 null uterine tissues. (E) Heterozygous intercrossing generated a similar ratio of male and female offspring at an expected Mendelian ratio (n = 6 litters). (F and G) Body weights of male (12 wk; n = 6) and female (8 wk; n = 50) rats did not differ significantly between wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null rats.

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic characterization of PgrΔ136E1 null female rats. (A) Temporal assessment of vaginal opening in wild-type (+/+) and PgrΔ136E1 null (−/−) female rats (n = 50/genotype). (B and C) Fertility tests and litter sizes from wild-type males mated to wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats and PgrΔ136E1 null males mated to wild-type females. (n = 6/mating scheme). (D) Sexual behavior in wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats. The ratio of female lordosis behavior to male mounting was quantified (n = 6/genotype; Movie S1). (E–J) Effects of exogenous gonadotropins on ovulation (E), ovarian weight (F), gene expression (G), and hematoxylin and eosin-stained paraffin-embedded ovarian tissue sections (H–J) in wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats (n = 6/genotype). (J) Trapped oocyte within an unruptured follicle. (K–M) Examination of artificial decidualization in wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats. (K) Schematic presentation of hormone treatments (E2, estradiol; P4, progesterone). (L) Gross responses of uterine tissue to a deciduogenic stimulus. (M) Quantification of uterine horn weights from nonstimulated (Nonstim) and stimulated (Stim) uterine horns (n = 6/genotype). (N and O) Mammary gland development in hormonally treated wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats. (P) Examination of acute uterine responses to progesterone in wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null rats. Progesterone responsive transcripts were monitored by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) (n = 6/group; C, vehicle; P, progesterone). Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Asterisks or different letters above bars signify differences between means (P < 0.05).

Fig. S3.

Follicular development and corpus luteum formation in ovaries from adult wild-type (+/+) and PgrΔ136E1 null (−/−) rats. Ovaries were collected from 8-wk-old female rats during proestrus of the estrous cycle. Tissues were fixed, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Note the presence of an unovulated oocyte trapped within a corpus luteum (see arrow) from a PgrΔ136E1 null rat.

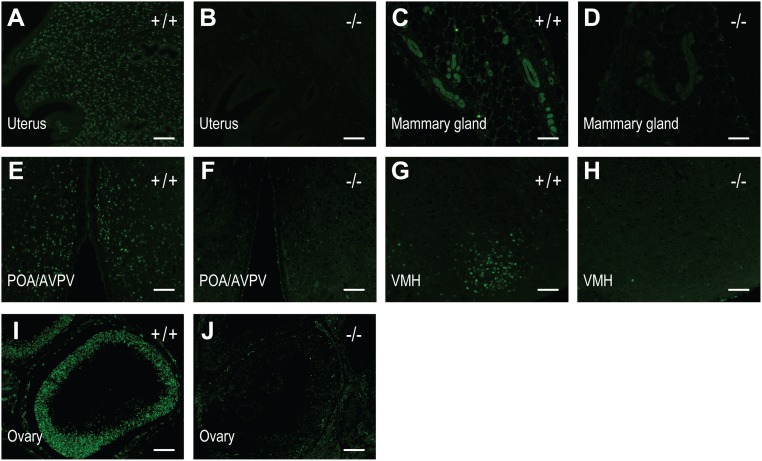

Fig. S2.

Immunohistochemical analyses of PGR expression in tissues from wild-type (+/+) and PgrΔ136E1 null (−/−) rats. (A and B) uterus; (C and D) mammary gland; (E and F) preoptic area/anteroventral periventricular nucleus (POA/AVPV); (G and H) ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH); (I and J) ovary. (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

Reproductive Cyclicity in the Female PgrΔ136E1 Null Rat.

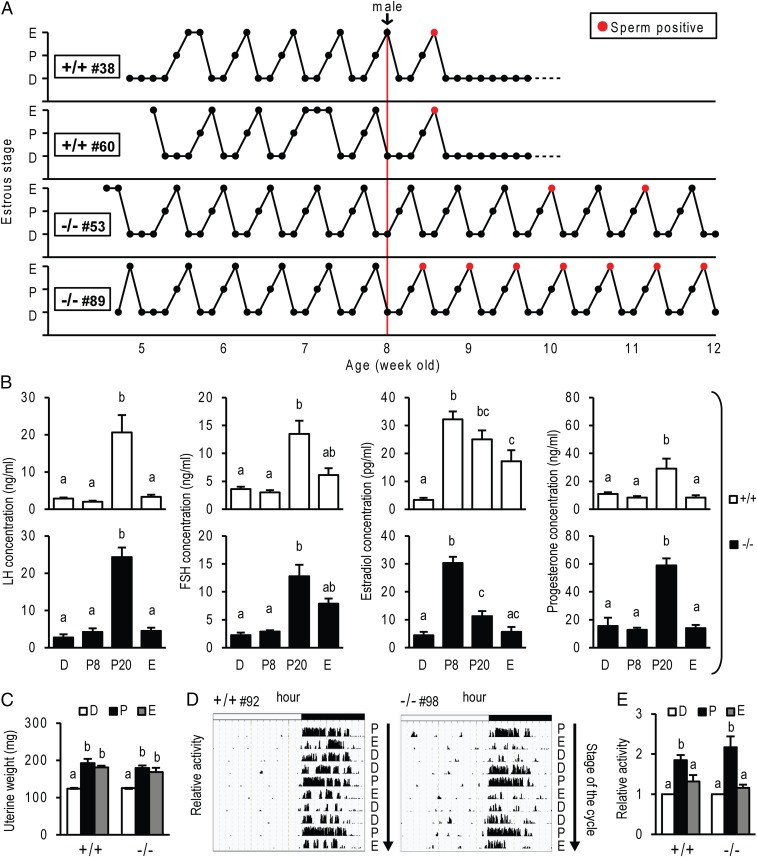

Further phenotypic characterization of the PgrΔ136E1 null rat revealed a fundamental distinction from the Pgr null mouse described in earlier reports (19, 20). PgrΔ136E1 null female rats display highly regular and well-defined reproductive cycles (Fig. 2), in contrast to the acyclic Pgr null female mouse (19). Cyclic changes in vaginal cytology, wheel running activity patterns, hormone levels, and uterine weights were observed in both wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats (Fig. 2 and Fig. S4). Although cyclicity was observed in both genotypes, some differences between wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats were noted, including cyclic changes in serum levels of sex steroid hormones (Fig. 2) and estrous cycle length (Fig. S4). Another unexpected observation was the detection of sperm in vaginal lavages from PgrΔ136E1 null female rats cohabiting cages with males (Fig. 2). In some instances, the presence of sperm in the vaginal lavage exhibited a cyclic pattern coinciding with the estrus stage of the estrous cycle. Although PgrΔ136E1 null female rats showed clear deficits in hormone-elicited sexual behavior (Fig. 1), in the gonadally intact state, some females allowed males to mount, exhibiting enough elements of sexual receptivity to permit vaginal deposition of sperm by the male (Movie S2). Such observations are consistent with previous reports showing estrogen alone can facilitate sexual behavior in the rat (21, 22). The mating never yielded a pregnancy or pseudopregnancy; instead, PgrΔ136E1 null female rats continued to cycle. These observations prompted further analysis of progesterone signaling on female cyclicity.

Fig. 2.

Reproductive cyclicity in wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats. (A) Representative estrous cycle profiles of wild-type (+/+) and PgrΔ136E1 null (−/−) female rats. Estrous cycles were monitored for 7 wk by daily inspection of vaginal cytology (D, diestrus; P, proestrus; E, estrus). The graphs also indicate when males were introduced. Red points indicate the presence of sperm in the vaginal lavage. (B) Cyclic changes in hormone concentrations in wild-type (Upper) and PgrΔ136E1 null (Lower) female rats. Blood was collected from 8–10-wk-old females at 0800 h on the first day of diestrus (D; n = 6/genotype), proestrus (P8; n = 6/genotype), and estrus (E; n = 6/genotype), and also at 2000 h on proestrus (P20; n = 14/genotype). Serum LH, FSH, estradiol, and progesterone were measured. (C) Cyclic changes in uterine weight in wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null rats. Uteri were collected from 8-wk-old female rats, weighed (n = 6/group), and analyzed histologically (Fig. S4). (D and E) Cyclic changes in activity patterns in wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null rats. Representative activity patterns during estrous cycles (D) and quantification of relative activity during each stage of the estrous cycle (E; n = 9/genotype) Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters above bars signify differences between means (P < 0.05).

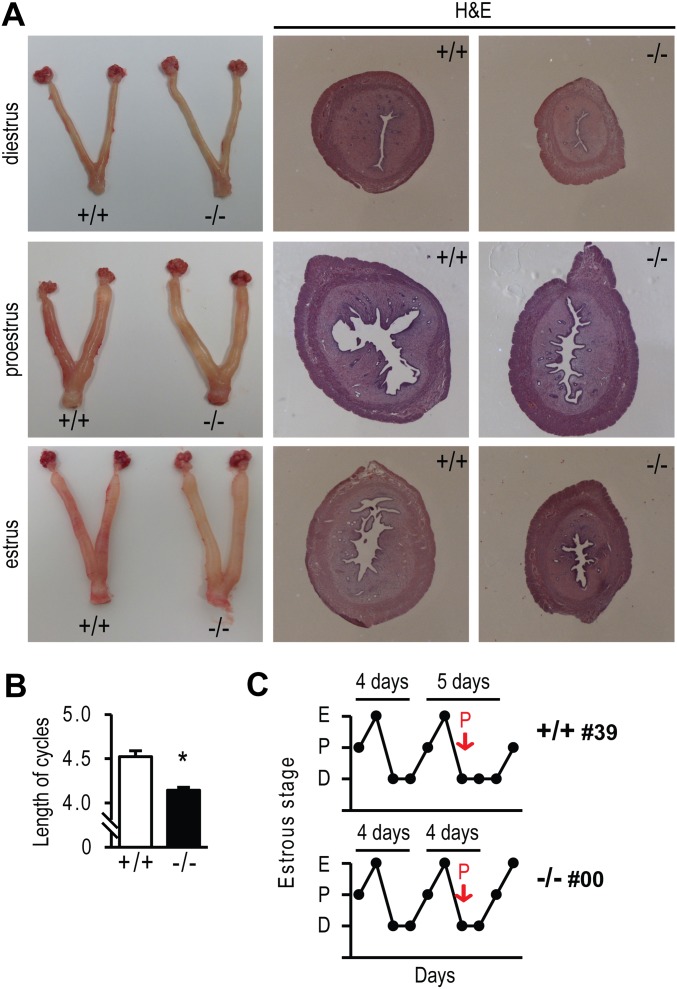

Fig. S4.

Cyclic changes in uterine morphology and estrous cycle length of wild-type (+/+) and PgrΔ136E1 null (−/−) female rats. (A) Uteri were collected from 8-wk-old female rats at diestrus, proestrus, and estrus stages of the estrous cycle. (Left) Gross images of uteri from wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null rats. The tissues were fixed, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). (Middle and Right) Images of the stained tissue sections. (B) Estrous cycle length was determined by assessing vaginal cytology from wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null rats (n = 50 rats/genotype). The asterisk indicates a significant difference between wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null rats (P < 0.05). (C) Progesterone administration (2 mg) at diestrus day 1 extended 4-d to 5-d cycles in wild-type females, but not in PgrΔ136E1 null females.

Progesterone Regulation of Reproductive Cycles.

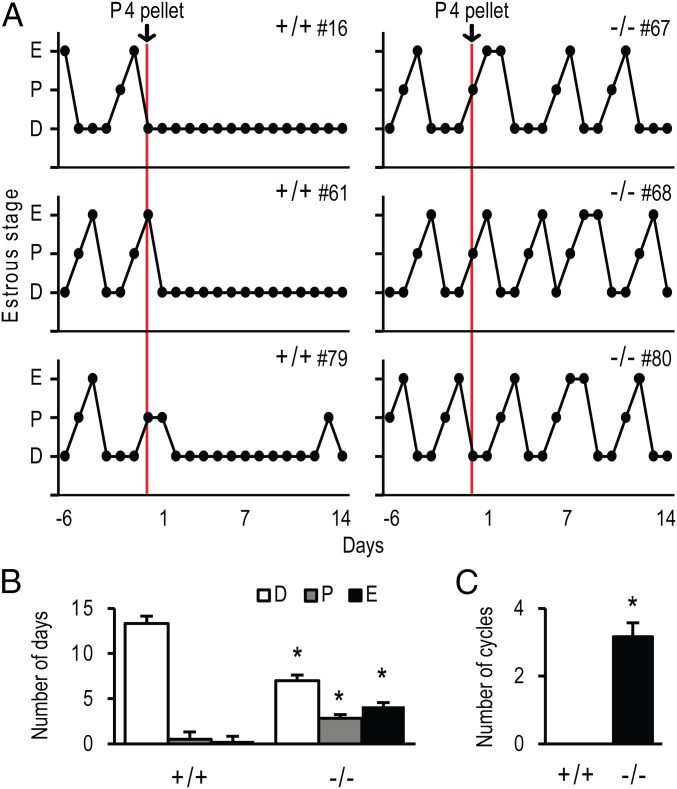

Evidence exists for progesterone acting independent of its nuclear receptor, PGR (23, 24). As a consequence, we examined the actions of exogenous progesterone treatment on cyclicity. Adult wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats were s.c. implanted with progesterone pellets (2 × 200 mg/rat), and vaginal cytology was monitored daily for 2 wk. As expected, wild-type females ceased cycling, whereas PgrΔ136E1 null females continued to display uninterrupted cycles (Fig. 3). In addition, progesterone administration could shift a 4-d to a 5-d estrous cycle in wild-type females, but not in PgrΔ136E1 null females (Fig. S4). These data demonstrate that PGR is involved in the negative feedback regulation of the female reproductive axis; however, PGR and progesterone signaling are dispensable for female reproductive cyclicity in the rat.

Fig. 3.

Cyclicity in progesterone treated wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats. Progesterone (P4) pellets (400 mg/rat) were implanted s.c. into cyclic wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats. Cyclicity was monitored by daily inspection of vaginal cytology for 14 d. (A) Vaginal cytology profiles for three representative wild-type and three representative PgrΔ136E1 null female rats are presented (D, diestrus; P, proestrus; E, estrus). (B and C) Quantification of the number of days in each stage of the estrous cycle and the number of cycles during the 14-d test period is presented (n = 6/genotype). Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences between wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null female rats (P < 0.05).

Generation and Phenotypic Characterization of a Mutation Targeting Exon 3 of the Rat Pgr Gene.

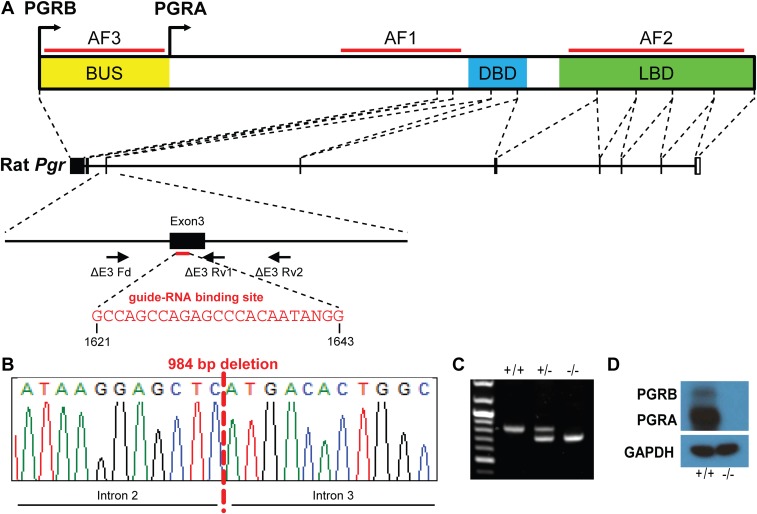

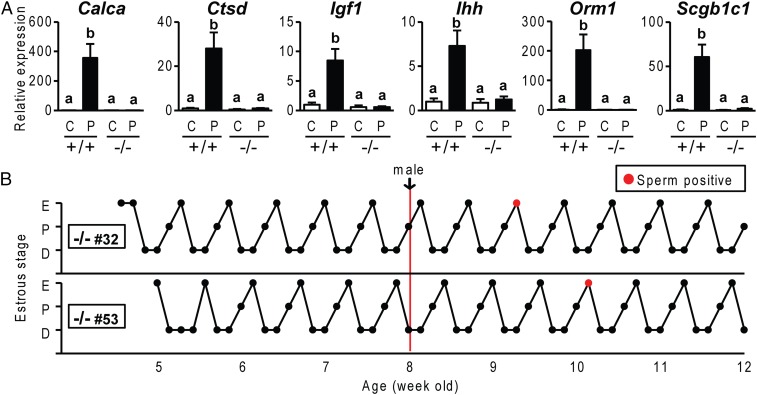

Because the Pgr mutation generated in the rat targeting exon 1 (PgrΔ136E1) differed from the previously characterized Pgr mutant mouse model (7), we sought to determine whether our phenotypic observations were biased by differences in the respective genomic manipulations. Clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/Cas9 genome editing was used to produce a rat model possessing a complete deletion of exon 3 (encoding the DNA binding domain) within the rat Pgr gene (PgrΔE3; Fig. S5). The PgrΔE3 mutation resulted in a null mutation and phenocopied the PgrΔ136E1 mutant rat, including the manifestation of reproductive cycles (Fig. 4). Thus, phenotypic characterization of two distinct genetic models, both possessing deficits in progesterone signaling, indicate that in the rat, female reproductive cyclicity is independent of PGR.

Fig. S5.

CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of exon 3 within the rat Pgr locus. (A) Schematic representation of the rat Pgr gene and the guide-RNA target site within exon 3 (NC_005107.3). (B) DNA sequence analysis showing a 984-bp deletion within the Pgr locus, resulting in deletion of exon 3 (ΔE3) and leading to a premature stop codon and a null mutation. (C) Offspring were backcrossed to wild-type rats, and heterozygous mutant rats were intercrossed to generate homozygous mutants. Wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and null (−/−) mutations were detected by PCR. (D) Western blot analysis of PGRA and PGRB protein species in wild-type and PgrΔE3 null uterine tissues. Note that PGR proteins were not detected in uterine tissues of PgrΔE3 null uterine tissues.

Fig. 4.

Phenotypic characterization of PgrΔE3 null female rats. (A) Examination of acute uterine responses to progesterone in wild-type (+/+) and PgrΔE3 null (−/−) rats. Progesterone-responsive transcripts were monitored by qRT-PCR (n = 6/group). Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Different letters above bars signify differences between means (P < 0.05). (B) Representative estrous cycle profiles of PgrΔE3 null females. Estrous cycles were monitored for 7 wk by daily inspection of vaginal cytology (D, diestrus; P, proestrus; E, estrus). The graphs also indicate when males were introduced. Red points indicate the presence of sperm in the vaginal lavage.

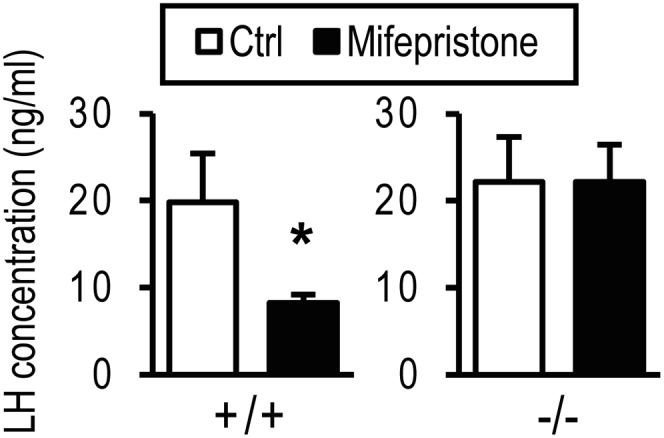

Actions of Mifepristone on the LH Surge.

Administration of progesterone receptor antagonists such as mifepristone (also known as RU486) have been consistently shown to disrupt the LH surge and interfere with cyclicity in the rat, monkey, and human (25–28), implicating progesterone signaling in the control of reproductive cyclicity. However, these findings are at odds with our observations with Pgr null rats. As a consequence, we examined the effects of mifepristone on the LH surge of wild-type and PgrΔ136E1 null rats. Mifepristone effectively inhibited the LH surge in wild-type rats, but not in PgrΔ136E1 null rats (Fig. 5). These results replicate earlier observations indicating that a progesterone receptor antagonist such as mifepristone disrupts the LH surge (25–28) and effectively demonstrates that these mifepristone actions are dependent on the PGR, but remain at odds with results with Pgr null rats. Thus, the downstream events after mifepristone engagement of PGR are fundamentally different from a biological response associated with the absence of PGR.

Fig. 5.

The effects of mifepristone on the LH surge. Wild-type (+/+) and PgrΔ136E1 null (−/−) female rats were monitored for cyclicity by daily inspection of vaginal cytology. At 1330 h on proestrus, animals were treated with vehicle (sesame oil) or mifepristone (6 mg/kg). Animals were killed at 2000 h on proestrus and blood collected for measurement of serum LH concentrations. Sample sizes: wild type-vehicle, n = 12; wild type-mifepristone, n = 14; PgrΔ136E1 null-vehicle, n = 8; PgrΔ136E1 null-mifepristone, n = 8. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between the vehicle and mifepristone treatments (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Progesterone signaling through the PGR is essential for female fertility. Such insights were first demonstrated through mouse mutagenesis (7) and are now also evident in rats with null mutations at the Pgr locus. The absence of a functional PGR is associated with deficits all along the reproductive axis (e.g., hypothalamus/pituitary, ovary, uterus, and mammary gland) (7, 19, 20; 29, 30). Remarkably, disruption of PGR signaling in the rat does not interfere with cyclic changes in vaginal cytology, physical activity, circulating hormone levels, or uterine structure. Although PGR is important in the negative feedback actions of progesterone on the reproductive axis (31), the integrity of this activity is not required for cyclicity. Such observations are provocative. They contrast with the reported phenotype of Pgr mutant mice (19, 20, 29, 30), insights gained from hormone replacement experiments (13, 32), and the reported neuroendocrine actions of progesterone receptor antagonists (25–28) and demand a rethinking of the hormonal control of reproductive cyclicity.

Cyclicity phenotypes of mice and rats with Pgr null mutations exhibit sharp differences (19, 20). Two strains of Pgr mutant rats, each possessing a distinct null mutation, exhibit cyclicity, whereas mice lacking a functional PGR do not cycle. Such a fundamental difference between these two murid species is unexpected. Species differences and experiential factors may affect substrates for progesterone action regulating the reproductive cycle. Mice are known to possess irregularities in their estrous cycle, as assessed by vaginal cytology, and are susceptible to interference by environmental and social factors, posing technical challenges not evident in the rat (33). Some of these potential factors affecting mouse reproductive cyclicity are transmitted through the olfactory system (34), a known substrate for progesterone action (35). Variability in the mouse estrous cycle is often addressed by experimental simulations of specific estrous cycle events, including pheromone-activated LH surges and hormone-activated LH surges in ovariectomized mice. Pgr mutant mice show deficits in both pheromone- and hormone-activated LH surges (19, 20, 29, 30). Because Pgr null rats exhibit robust and well-defined reproductive cycles, it is not necessary to artificially simulate events within the estrous cycle, making direct comparisons between mouse and rat Pgr mutants problematic. Observations with the Pgr null rat bring into question the involvement of progesterone and PGR signaling as an essential regulator of the female reproductive cycle. Alternatively, a mouse-centric interpretation may preserve the importance of PGR signaling in cyclicity, and instead focus on the emergence of a compensatory pathway controlling cyclicity in the Pgr null rat. Nevertheless, our observations highlight a practical benefit of genome editing, which enables the experimental implementation of the most appropriate animal models for physiologic investigation.

In addition to the acyclic phenotype of the Pgr null mouse, the actions of progesterone receptor antagonists have been used to support a role for progesterone signaling in the regulation of the female reproductive cycle. Our findings in Pgr null rats indicate that the actions of a PGR antagonist, such as mifepristone, in the presence of PGR is fundamentally different from the biology associated with the absence of PGR. In the present study, mifepristone treatment inhibited the LH surge in a PGR-dependent manner, whereas the LH surge occurred uninterrupted in Pgr null rats. This may be surprising to some, but not to those familiar with the molecular actions of mifepristone. Mifepristone physically interacts with PGR, facilitating the assembly of protein complexes distinct from those activated by PGR agonists (36, 37); differentially regulates chromatin remodeling (38); and guides ligand receptor complexes to unique regions within the genome (39). In addition, transcriptional targets of PGR within the mouse uterus identified through the use of mifepristone as an antagonist of endogenous ligand action (40) versus progesterone actions in wild-type and Pgr null tissues yield different profiles (41). Thus, caution is required in interpreting pharmacologic manipulations versus genetic interventions. Mifepristone does not simply block progesterone action through its interactions with the PGR but also creates epifunctions not normally ascribed to the PGR.

The phenotypic description of Pgr null rats resembles aspects of those previously described for a patient with progesterone resistance and normal menstrual cycles (42, 43). Collectively, these observations suggest that female reproductive cycles are driven by cyclic changes in circulating estradiol and are independent of progesterone signaling. Although the administration of compounds with progestagenic activities can interfere with female reproductive cycles, forming the basis of their use as oral contraceptives (44), endogenous progesterone signaling is not required for cyclicity in the rat, a model organism for mammalian reproduction, opening the question of its involvement in regulating female reproductive cyclicity in other species.

Methods

The University of Kansas Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols performed. Animals, generation of targeted Pgr mutations, phenotypic characterization of wild-type and Pgr null rats, hormone measurements, Western blotting, immunohistochemistry, whole-mount mammary gland preparations, and statistical analyses are provided in the SI Methods.

SI Methods

Animals.

Holtzman Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Envigo and maintained in a 14 h light:10 h dark photoperiod (lights on at 0600 h). The University of Kansas Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols performed.

Generation of Targeted Pgr Mutations.

Targeted mutations were generated using genome editing strategies (45, 46). Zinc finger nuclease constructs specific for the rat Pgr gene were designed, assembled, and validated by Sigma-Aldrich. Selected zinc finger nucleases were targeted to exon 1 of the Pgr gene (target sequence: AGCCATCTCAGCAGCctgctACGGTGGAGGTGGAGGAG, corresponding to nucleotides 632–646 and 652–669, NM_022847.1; Fig. S1). The CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system was also used to generate mutations at the rat Pgr locus. A guide RNA targeting exon 3 of the Pgr gene (target sequence: GCCAGCCAGAGCCCACAATANGG; nucleotides 1,621–1,643; NM_022847.1) was designed, assembled, and validated by the Genome Engineering Center, Washington University. Genome editing constructs were microinjected into single-cell rat embryos. Injected embryos were transferred to oviducts of day 0.5 pseudopregnant rats. Offspring were screened for mutations at specific target sites within the Pgr gene. For initial screening, genomic DNA was purified from tail-tip biopsies, using the E.Z.N.A. tissue DNA kit (Omega Bio-Tek). Potential mutations within 5,000 bp at each target locus were screened by PCR, and precise boundaries of deletions determined by DNA sequencing (Genewiz Inc.). Founders were backcrossed with wild-type rats to demonstrate germ line transmission. A mutant rat strain possessing a 136-bp deletion within exon 1 of the Pgr gene (PgrΔ136E1; Fig. S1) was generated using zinc finger nuclease-mediated genome editing, and a second mutant rat strain possessing a 984-bp deletion including all of exon 3 of the Pgr gene (PgrΔE3; Fig. S5) was produced using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Phenotypic characterization was performed on offspring from intercrosses of heterozygous rats. Genotyping was performed using PCR on genomic DNA purified from tail-tip biopsies, using the REDExtract-N-Amp tissue PCR kit (Sigma-Aldrich), with specific sets of primers shown in Table S1. Mutant rat models are available at the Rat Resource & Research Center (University of Missouri).

Table S1.

Primer sequences used for genotyping

| Target locus | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| Exon 1 | acgcatcgtctgtagtctcg | gtaaactgggaacccgtcct |

| Exon 3* | gttgtgacccagcattcagg | ctaccttccatcgccctctt |

| Exon 3* | — | gcactccatgtcagcttctt |

PCR was performed with combination of one forward primer and two different reverse primers.

Phenotypic Characterization.

The reproductive phenotypes of wild-type and mutant rats were examined. Immature females were monitored for vaginal opening. After vaginal opening, vaginal lavages were collected daily and cytology examined microscopically to determine reproductive cyclicity and stages of the estrous cycle for up to 5 mo. At 8–10 wk of age, females were weighed and euthanized at key phases of the estrous cycle (47, 48). Blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture. Ovary, uterus, mammary gland, brain, and pituitary were collected, weighed, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until they were processed for RNA or protein analyses. Initial histological examinations for all tissues were performed on paraffin-embedded hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections.

Fertility tests.

Fertility was assessed by cohabiting 12-wk-old males with 8-wk-old female rats for 12 wk and recording pregnancies and litter sizes. The breeding combinations included wild-type males with wild-type or homozygous Pgr mutant females and homozygous Pgr mutant males with wild-type females.

Ovulatory responses to exogenous gonadotropins.

At postnatal day 30, female rats were tested for responsiveness to exogenous gonadotropins (49). Females were treated intraperitoneally with 30 IU equine chorionic gonadotropin (CG) at 1500 h, and 48 h later, 30 IU of human CG (hCG) was injected. Twenty-four h after the hCG injection, animals were euthanized, oocytes were recovered from the oviduct, cumulus cells were removed using hyaluronidase (Sigma Aldrich), and oocytes were counted. Ovaries were also collected, weighed, and processed for histological analysis. Additional ovaries from animals treated with gonadotropins were collected 6 h after hCG for PGR expression and at 12 h after hCG for RNA isolation and analysis of specific transcript concentrations by qRT-PCR. Primer sequences used in the analyses are shown in Table S2.

Table S2.

Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR

| Target gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Accession number |

| 18s | gcaattattccccatgaacg | ggcctcactaaaccatccaa | NR_046237.1 |

| Hif2a | gcgacaatgacagctgacaa | cgcatgatggaggctttgtc | NM_023090.1 |

| Adamts1 | ttccacatcctgaggcgaag | gctggacacaaatcgcttct | NM_024400.2 |

| Edn2 | tgtgtgtacttctgccacct | gtctctaacacagcagcagg | NM_012549.2 |

| Calca | cctttcctggttgtcagcat | ggcgagcttcttcttcactg | NM_017338.2 |

| Ctsd | gccaagtttgatggcatctt | gctccccgtggtagtatctg | NM_134334.2 |

| Igf1 | ggcattgtggatgagtgttg | gtcttgggcatgtcagtgtg | NM_178866.4 |

| Ihh | gagctcacccccaactacaa | tgacagagatggccagtgag | NM_053384.1 |

| Scgb1c1 | ggaattcctgcaaacactcct | gggctgcttatgtgtcctct | NM_001107561.1 |

| Orm1 | tgcccatttgatagtgctga | tggaatattttccgcagctc | NM_053288.2 |

Uterine responses to steroid hormones.

Adult uterine responsiveness to steroid hormones was assessed by examining artificial decidual reactions in females treated with estradiol and progesterone and by monitoring acute uterine gene expression responses to administered progesterone (49, 50). In both the experiments, female rats were ovariectomized at 8 wk of age and rested for 2 wk before experimentation.

For the induction of artificial decidualization, ovariectomized female rats were treated with an empirically determined hormone regimen known to appropriately prepare the uterus for embryo implantation (51, 52). Decidualization was induced via scratching the antimesometrial endometrial surface of one uterine horn (52). Uteri were collected 4 d after the decidualization stimulus and weighed.

For the assessment of acute responses to progesterone, ovariectomized female rats were s.c. injected with vehicle (sesame oil) or progesterone (40 µg/g body weight). Uteri were collected 9 h after the injection and processed for RNA isolation. Expression of uterine progesterone responsive genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Primer sequences used in the analyses are shown in Table S2.

Sexual behavior tests.

Sexual behavior was monitored under dim red light, as reported previously (7, 53, 54). Ovariectomized females were treated with s.c. injection of estradiol benzoate (10 µg) and 48 h later with a s.c. injection of progesterone (500 µg), each delivered in a vehicle of sesame oil. Six h after the progesterone injection, females were introduced into the cages of sexually experienced adult fertile males. The males were placed in cages for 30 min before initiation of monitoring. Sexual behavior tests were continued for 30 min. If mounting behavior was not observed within 30 min, females were placed into a cage with a different male. Only mounts in which the female showed full arching of the back were scored as lordosis. The ratio of female lordosis behavior to male mounting was quantified.

Wheel running activity.

Wheel revolutions were counted by magnetic sensor-equipped wheel cages to determine daily activity during the estrous cycle. Data were recorded every 5 min, using Vital View software (Respironics), and were analyzed by ActiView software (Respironics). Six-week-old females were placed into wheel cages. After 2 wk of acclimation, activity was monitored for 2 wk and correlated to the stage of the estrous cycle assessed by daily examination of vaginal cytology.

Effects of exogenous progesterone on the estrous cycle.

Cycling female rats were s.c. implanted with progesterone pellets (2 × 200 mg; Innovative Research of America). After implantation of the pellets, vaginal cytology was monitored daily for 14 d. In a separate experiment, females with 4-d cycles were administered progesterone by s.c. injection (2 mg in sesame oil) on diestrus day 1, and vaginal cytology was monitored.

Hormone Measurements.

Blood samples were collected at 800 h during diestrus, proestrus, and estrus, and also at 2000 h on proestrus, coinciding with the preovulatory surge of LH (47, 48). Serum LH and FSH concentrations were determined by Milliplex MAP kits (Millipore). Serum estradiol and progesterone concentrations were measured by RIA, as previously described (55).

Western Blotting and Immunohistochemistry.

Expression of PGR proteins was determined by Western blotting and immunohistochemistry. A rabbit monoclonal antibody (D8Q2J; Cell Signaling Technology) that recognizes the carboxyl terminus of PGR was used for both Western blotting and immunohistochemistry. Immunostaining was examined by immunofluorescence microscopy (Leica).

Whole-Mount Mammary Gland Staining (56).

Mammary glands were dissected and spread onto glass slides. After fixation with Carnoy’s fixative, glands were stained with Carmine aluminum solution. Washed glands were then cleared by xylene and examined microscopically.

Statistical Analysis.

Values reported graphically are presented as the mean ± SEM. Comparisons of two means were analyzed by Student’s t test, whereas multiple comparisons were analyzed by analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s test, using GraphPad prism software (GraphPad Software).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Melissa Larson in the University of Kansas Medical Center Transgenic and Gene Targeting Institutional Facility, Regan Scott for technical assistance, and Stacy McClure for administrative assistance. The research was supported by NIH Grants HD066406 and OD01478 and by individual postdoctoral fellowships from the American Heart Association and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to K.K.) and Lalor Foundation (to P.D.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1601825113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hawkins SM, Matzuk MM. The menstrual cycle: Basic biology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1135:10–18. doi: 10.1196/annals.1429.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beshay VE, Carr BR. Hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and control of the menstrual cycle. In: Falcone T, Hurd WW, editors. Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery: A Practical Guide. Springer; New York: 2012. pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman RL, Karsch FJ. Pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone: Differential suppression by ovarian steroids. Endocrinology. 1980;107(5):1286–1290. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-5-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plant TM. Gonadal regulation of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone release in primates. Endocr Rev. 1986;7(1):75–88. doi: 10.1210/edrv-7-1-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke IJ. Control of GnRH secretion: One step back. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32(3):367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lubahn DB, et al. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(23):11162–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lydon JP, et al. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1995;9(18):2266–2278. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupont S, et al. Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors α (ERalpha) and β (ERbeta) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development. 2000;127(19):4277–4291. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: What have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev. 1999;20(3):358–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conneely OM, Mulac-Jericevic B, DeMayo F, Lydon JP, O’Malley BW. Reproductive functions of progesterone receptors. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:339–355. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewitt SC, Korach KS. Oestrogen receptor knockout mice: Roles for oestrogen receptors alpha and beta in reproductive tissues. Reproduction. 2003;125(2):143–149. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long JA, Evans HM. Memoirs of the University of California. Vol 6 University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1922. The oestrous cycle in the rat and its associated phenomena. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett JW. Progesterone and estrogen in the experimental control of ovulation time and other features of the estrous cycle in the rat. Endocrinology. 1948;43(6):389–405. doi: 10.1210/endo-43-6-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards JS, Midgley AR., Jr Protein hormone action: A key to understanding ovarian follicular and luteal cell development. Biol Reprod. 1976;14(1):82–94. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod14.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine JE. New concepts of the neuroendocrine regulation of gonadotropin surges in rats. Biol Reprod. 1997;56(2):293–302. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matzuk MM, Lamb DJ. Genetic dissection of mammalian fertility pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(Suppl):s41–s49. doi: 10.1038/ncb-nm-fertilityS41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rumi MA, et al. Generation of Esr1-knockout rats using zinc finger nuclease-mediated genome editing. Endocrinology. 2014;155(5):1991–1999. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robker RL, et al. Progesterone-regulated genes in the ovulation process: ADAMTS-1 and cathepsin L proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(9):4689–4694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080073497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chappell PE, Lydon JP, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW, Levine JE. Endocrine defects in mice carrying a null mutation for the progesterone receptor gene. Endocrinology. 1997;138(10):4147–4152. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chappell PE, et al. Absence of gonadotropin surges and gonadotropin-releasing hormone self-priming in ovariectomized (OVX), estrogen (E2)-treated, progesterone receptor knockout (PRKO) mice. Endocrinology. 1999;140(8):3653–3658. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson JM, Rodgers CH, Smith ER, Bloch GJ. Stimulation of female sex behavior in adrenalectomized rats with estrogen alone. Endocrinology. 1968;82(1):193–195. doi: 10.1210/endo-82-1-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaff D. Nature of sex hormone effects on rat sex behavior: Specificity of effects and individual patterns of response. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1970;73(3):349–358. doi: 10.1037/h0030242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas P, Pang Y. Membrane progesterone receptors: Evidence for neuroprotective, neurosteroid signaling and neuroendocrine functions in neuronal cells. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;96(2):162–171. doi: 10.1159/000339822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pru JK, Clark NC. PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 in uterine physiology and disease. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:168. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins RL, Hodgen GD. Blockade of the spontaneous midcycle gonadotropin surge in monkeys by RU 486: A progesterone antagonist or agonist? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63(6):1270–1276. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-6-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao IM, Mahesh VB. Role of progesterone in the modulation of the preovulatory surge of gonadotropins and ovulation in the pregnant mare’s serum gonadotropin-primed immature rat and the adult rat. Biol Reprod. 1986;35(5):1154–1161. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod35.5.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spitz IM, Shoupe D, Sitruk-Ware R, Mishell DR., Jr Response to the antiprogestagen RU 486 (mifepristone) during early pregnancy and the menstrual cycle in women. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1989;37:253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer-Dantoin AC, Tabesh B, Norgle JR, Levine JE. RU486 administration blocks neuropeptide Y potentiation of luteinizing hormone (LH)-releasing hormone-induced LH surges in proestrous rats. Endocrinology. 1993;133(6):2418–2423. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White MM, Sheffer I, Teeter J, Apostolakis EM. Hypothalamic progesterone receptor-A mediates gonadotropin surges, self priming and receptivity in estrogen-primed female mice. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;38(1-2):35–50. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephens SBZ, et al. Absent progesterone receptor in kisspeptin neurons disrupts the LH surge and impairs fertility in female mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156(9):3091–3097. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skinner DC, et al. The negative feedback actions of progesterone on gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion are transduced by the classical progesterone receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(18):10978–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine JE, Chappell PE, Schneider JS, Sleiter NC, Szabo M. Progesterone receptors as neuroendocrine integrators. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2001;22(2):69–106. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cora MC, Kooistra L, Travlos G. Vaginal cytology of the laboratory rat and mouse: Review and criteria for the staging of the estrous cycle using stained vaginal smears. Toxicol Pathol. 2015;43(6):776–793. doi: 10.1177/0192623315570339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aron C. Mechanisms of control of the reproductive function by olfactory stimuli in female mammals. Physiol Rev. 1979;59(2):229–284. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dey S, et al. Cyclic regulation of sensory perception by female hormone alters behavior. Cell. 2015;161(6):1334–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Z, et al. Coactivator/corepressor ratios modulate PR-mediated transcription by the selective receptor modulator RU486. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(12):7940–7944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122225699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han SJ, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Distinct temporal and spatial activities of RU486 on progesterone receptor function in reproductive organs of ovariectomized mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148(5):2471–2486. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rayasam GV, et al. Ligand-specific dynamics of the progesterone receptor in living cells and during chromatin remodeling in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(6):2406–2418. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2406-2418.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin P, et al. Genome-wide progesterone receptor binding: Cell type-specific and shared mechanisms in T47D breast cancer cells and primary leiomyoma cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheon YP, et al. A genomic approach to identify novel progesterone receptor regulated pathways in the uterus during implantation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(12):2853–2871. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeong JW, et al. Identification of murine uterine genes regulated in a ligand-dependent manner by the progesterone receptor. Endocrinology. 2005;146(8):3490–3505. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keller DW, Wiest WG, Askin FB, Johnson LW, Strickler RC. Pseudocorpus luteum insufficiency: A local defect of progesterone action on endometrial stroma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;48(1):127–132. doi: 10.1210/jcem-48-1-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chrousos GP, et al. Progesterone resistance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1986;196:317–328. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5101-6_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sitruk-Ware R, Nath A, Mishell DR., Jr Contraception technology: Past, present and future. Contraception. 2013;87(3):319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geurts AM, et al. Generation of gene-specific mutated rats using zinc-finger nucleases. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;597:211–225. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-389-3_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao Y, et al. CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing in the rat via direct injection of one-cell embryos. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(10):2493–2512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butcher RL, Collins WE, Fugo NW. Plasma concentration of LH, FSH, prolactin, progesterone and estradiol-17β throughout the 4-day estrous cycle of the rat. Endocrinology. 1974;94(6):1704–1708. doi: 10.1210/endo-94-6-1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith MS, Freeman ME, Neill JD. The control of progesterone secretion during the estrous cycle and early pseudopregnancy in the rat: Prolactin, gonadotropin and steroid levels associated with rescue of the corpus luteum of pseudopregnancy. Endocrinology. 1975;96(1):219–226. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dhakal P, et al. Neonatal progesterone programs adult uterine responses to progesterone and susceptibility to uterine dysfunction. Endocrinology. 2015;156(10):3791–3803. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Konno T, et al. Subfertility linked to combined luteal insufficiency and uterine progesterone resistance. Endocrinology. 2010;151(9):4537–4550. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kennedy TG. Intrauterine infusion of prostaglandins and decidualization in rats with uteri differentially sensitized for the decidual cell reaction. Biol Reprod. 1986;34(2):327–335. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod34.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Feo VJ. Temporal aspect of uterine sensitivity in the pseudopregnant or pregnant rat. Endocrinology. 1963;72:305–316. doi: 10.1210/endo-72-2-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hardy DF, DeBold JF. The relationship of exogenous hormones and the display of lordosis by the female rat. Horm Behav. 1971;2(4):287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfaff DW, Lewis C. Film analyses of lordosis in female rats. Horm Behav. 1974;5(4):317–335. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(74)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terranova PF, Garza F. Relationship between the preovulatory luteinizing hormone (LH) surge and androstenedione synthesis of preantral follicles in the cyclic hamster: Detection by in vitro responses to LH. Biol Reprod. 1983;29(3):630–636. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod29.3.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McGinley JN, Thompson HJ. Quantitative assessment of mammary gland density in rodents using digital image analysis. Biol Proced Online. 2011;13(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1480-9222-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.