Significance

Multiple sclerosis (MS) imposes substantial economic burdens on patients, their families, and society. Until now, there are few therapies available, but often unattractive parenteral application or severe side effects are serious issues. This study highlights the use of circular peptides as orally active T-cell-specific immunosuppressive therapeutics against the MS model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, without inducing major adverse effects. Our work provides a proof of principle that nature-derived cyclic peptides serve as oral active therapeutics, utilizing their intrinsic bioactivity and stable three-dimensional structure. Cyclotides are considered a combinatorial peptide library and they can be anticipated to complement the existing collections of natural products that are used in drug discovery.

Keywords: cyclic peptides, multiple sclerosis, immunopharmacology, plant natural product, drug discovery

Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common autoimmune disease affecting the central nervous system. It is characterized by auto-reactive T cells that induce demyelination and neuronal degradation. Treatment options are still limited and several MS medications need to be administered by parenteral application but are modestly effective. Oral active drugs such as fingolimod have been weighed down by safety concerns. Consequently, there is a demand for novel, especially orally active therapeutics. Nature offers an abundance of compounds for drug discovery. Recently, the circular plant peptide kalata B1 was shown to silence T-cell proliferation in vitro in an IL-2–dependent mechanism. Owing to this promising effect, we aimed to determine in vivo activity of the cyclotide [T20K]kalata B1 using the MS mouse model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Treatment of mice with the cyclotide resulted in a significant delay and diminished symptoms of EAE by oral administration. Cyclotide application substantially impeded disease progression and did not exhibit adverse effects. Inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation and the reduction of proinflammatory cytokines, in particular IL-2, distinguish the cyclotide from other marketed drugs. Considering their stable structural topology and oral activity, cyclotides are candidates as peptide therapeutics for pharmaceutical drug development for treatment of T-cell-mediated disorders.

Natural products play a pivotal role in modern drug discovery (1), and they continue to provide innovative lead compounds currently entering clinical trials (2). The increasing interest for peptide-based drugs has boosted development of nature-derived peptides for therapeutic applications (3, 4). Bioactive peptides exist in all organisms, and physiologically they function as peptide hormones for cellular signaling, secretory peptides for interspecies communication, predatory peptide toxins, or antimicrobial host-defense peptides (5, 6). These molecules have evolved over millions of years into a structurally sophisticated collection of compounds to modulate a diverse set of target proteins. One of the most extensively studied family of bioactive peptides are found in the venoms of marine cone snails (7). For instance, the ω-conotoxin MVIIA (8) is a potent blocker of neuronal receptors and ion channels and was approved for clinical use in 2004 (ziconotide, Prialt) to treat chronic pain (9). However, the intrathecal application route reduces the attractiveness of this elsewise promising medication (10, 11), and hence the major drawbacks of this cone-snail toxin are its inability to cross the blood–brain barrier, low stability, and lack of oral activity. In fact, this limits the clinical use of other peptide pharmaceuticals (3).

Recent studies referred to the immunosuppressive effects of the circular peptide kalata B1 (kB1) on activated human T lymphocytes in vitro (12, 13). This plant-derived peptide belongs to the family of cyclotides well-known for their cyclic cystine-knot topology. This unique 3D fold confers them intrinsic stability to resist chemical, enzymatic, and thermal degradation (14). Therefore, cyclotides have become attractive tools in chemical biology and drug development (15), for instance as templates for molecular grafting applications (16) as well as for receptor ligand design (17), because they presumably exhibit activity following oral administration (18).

Cyclotides, in particular [T20K]kB1, inhibit T-cell proliferation by down-regulation of IL-2 release as well as IL-2R/CD25 surface expression (13). The cytokine IL-2 physiologically plays an important role in T-lymphocyte activation and acts as an autocrine factor to stimulate T-cell proliferation (19). Enhanced or continuous T-cell activation is a major cause of autoimmune disorders and can lead to persistent inflammation, causing tissue and organ damage (20). Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common type of autoimmune disease in young adults, which is characterized by sustained inflammation of the CNS. Autoreactive T lymphocytes of the TH17 subset target myelin brain antigens, eliciting inflammatory cell influx into the CNS, demyelination, axonal damage, and neuronal degradation (21, 22). Several therapeutics targeting different aspects to modulate or suppress T-cell signaling are available, but the parenteral administration route of many drugs reduces their attractiveness for chronic treatment (23). Only three marketed compounds that are specific for MS treatment are active via oral administration [i.e., dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, and fingolimod (Gilenya), a sphingosine 1-phospate receptor ligand]; however, many and severe side effects limit their therapeutic use (24).

Owing to their remarkable stability and hydrophobic surface properties, cyclotides are ideally suited for oral administration. Their immunosuppressive properties have been confirmed on human T cells. In the present study we demonstrate the effect of the cyclotide [T20K]kB1 in the state-of-the-art in vivo model for MS, the murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) assay, after oral administration. In particular, we investigated their efficacy to reduce the polarization of pathogenic TH17 cells and the rate of relapse by prophylactic administration of cyclotides before disease induction. Moreover, we analyzed the therapeutic application of cyclotides during disease progression, which potently ameliorated the EAE symptoms. Biodistribution and systemic uptake of the peptide drugs has been monitored using the in vivo imaging system (IVIS) and mass spectrometry, respectively. Our observations suggest cyclotides may be good candidates as MS therapeutics, without causing any adverse effects based on preliminary toxicity studies in mice. The results provide proof of principle for the application of an orally active cyclic peptide drug in the treatment of autoimmune disorders and could inspire pharmacological screening as well as preclinical development of other peptide-based therapeutics of natural origin (25).

Results

Modulation of T-Cell Proliferation by [T20K]kalata B1.

Extensive screening efforts for the discovery of novel nature-derived drugs has led to the identification of antiproliferative properties of the cyclotide kB1 toward human activated lymphocytes in vitro (13). Recently, structure-activity screening of cyclotides isolated from the plant Oldenlandia affinis (Rubiaceae) established [T20K]kB1 as an active lead compound to inhibit T-cell proliferation and, interestingly, replacement of valine to the positively charged lysine in loop 2 resulted in a loss of activity in vitro (13). In the current work, [T20K]kB1 was synthesized following a modified protocol for the generation of thioester peptides and subsequent cyclization by native chemical ligation (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1) (26, 27). To evaluate the immunosuppressive effects of cyclotides in vivo, the murine T-cell autoimmune-specific EAE was investigated as a model for human MS. In EAE, autoreactive CD4+ T cells of the subtype TH17 are the major cause initiating and provoking demyelination of the CNS that leads to the typical appearance of paralysis symptoms (28). As a preliminary experiment, [T20K]kB1 and [V10K]kB1 were incubated at different concentrations with mouse immune cells ex vivo, which were isolated from spleens of EAE-induced, viz. myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35–55; MOG)-immunized mice, to confirm the immunosuppressive effects previously observed in human T cells (13). The proliferation of T cells, measured by flow cytometry, as well as the autocrine acting proliferation-supporting cytokine IL-2 and the TH1 and TH17 signature cytokines IFN-γ and IL-17A in the supernatant of MOG-restimulated cells (Fig. S2 A–C), were down-regulated by [T20K]kB1 in a concentration-dependent fashion; the inactive control cyclotide [V10K]kB1 had significantly less effect in reduction of cytokine secretion. Cyclosporine A, which leads to IL-2 suppression by modulating calcineurin activity (29), was used as a positive control to confirm the antiproliferative properties of the cyclotide. Down-regulation of cytokine-related mRNAs caused by [T20K]kB1 was confirmed by quantitative PCR (Fig. S2D). Finally, significant antiproliferative effects and a reduction of inflammatory cytokine release of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A has been demonstrated by restimulation of splenic T cells isolated from 2D2 MOG–specific TCR transgenic mice following cyclotide [T20K]kB1 treatment (Fig. S2E).

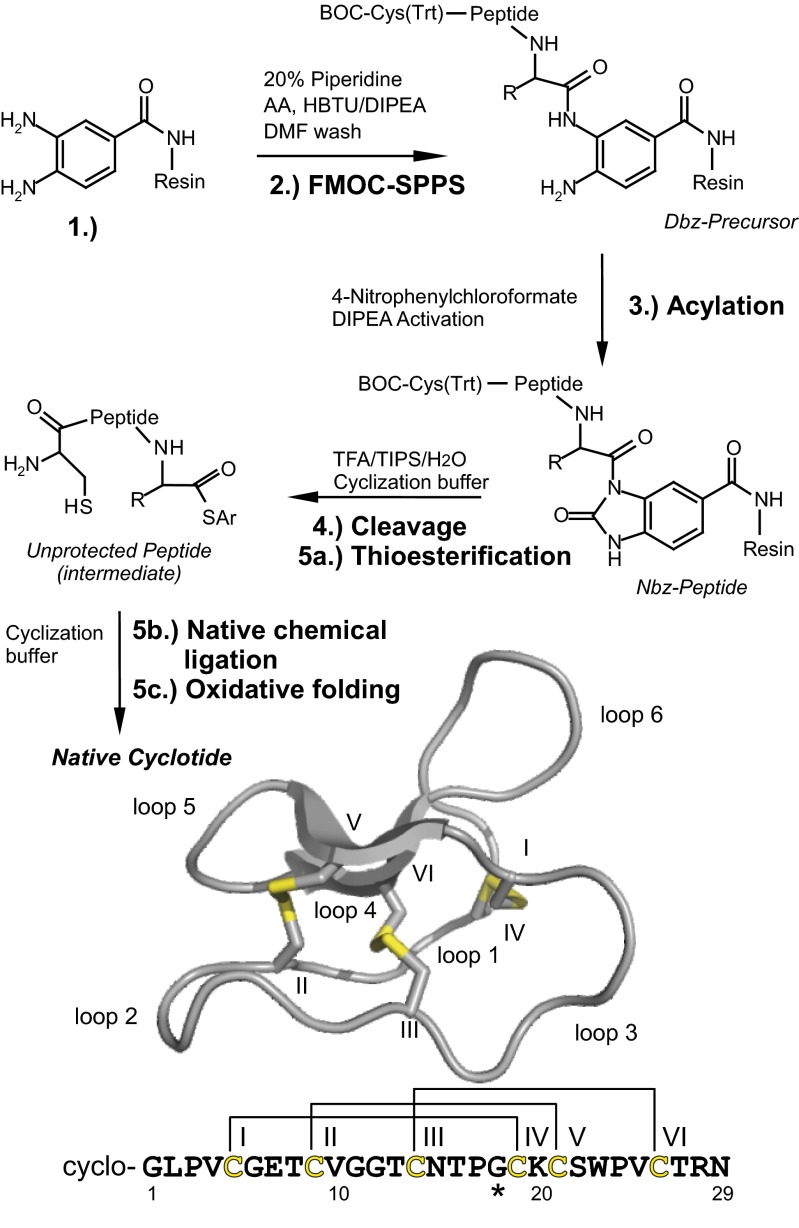

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of cyclotides. Cyclotides were assembled as linear precursors using FMOC chemistry, and cyclized using native chemical ligation. (1) Dawson’s resin containing di-Fmoc-3,4-diaminobenzoic acid (Dbz) as linker is the starting point. (2) Couplings are performed using microwave-assisted FMOC synthesis (asterisk marks the first amino acid; the last amino acid is a BOC-protected cysteine). (3) Acylation and activation of the resin bound Dbz-precursor to yield the N-acylurea peptide (Nbz-peptide). (4) Full deprotection and resin cleavage of the Nbz-peptide in one step (Ar, Aryl). Peptide cyclization (5a) via thioesterification, (5b) S, N-intramolecular acyl shift and native chemical ligation and (5c) oxidative folding to yield cyclotides with the native fold. Ribbon representation of a cyclotide (kalata B1, PDB ID code 1NB1) and sequence of [T20K]kalata B1 are shown. Cysteines, disulfide bonds (yellow), and intercysteine loops are indicated.

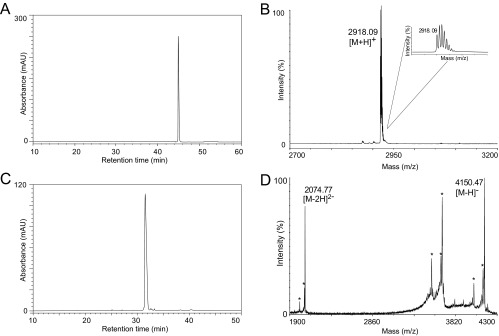

Fig. S1.

Quality control of peptide synthesis and derivatization. (A) Native folded peptide [T20K]kB1 was purified with preparative and semipreparative HPLC and final peptide was evaluated for purity by analytical HPLC. A chromatogram with the corresponding A280 trace is shown indicating a purity ≥95%. (B) Peptide [T20K]kB1 was evaluated via MALDI-MS for identity and a representative spectrum is shown indicating the mass 2,918.09 m/z [M+H]+. (C) Labeled [T20K-VivoTag]kB1 was purified from nonlabeled peptide, and excess of labeling reagent by semipreparative HPLC. Purity of ≥95% is indicated by an analytical HPLC chromatogram showing the A280 trace of the analysis. (D) Purified peptide [T20K-VivoTag]kB1 was analyzed with MALDI-TOF in the negative ionization mode. Mass signals for the [M-H]− ion (4,150.47 m/z) and for the [M-2H]2- ion (2,074.77 m/z) were recorded. The spectrum shows several degradation artifacts indicated by asterisks due to the laser-induced desorption.

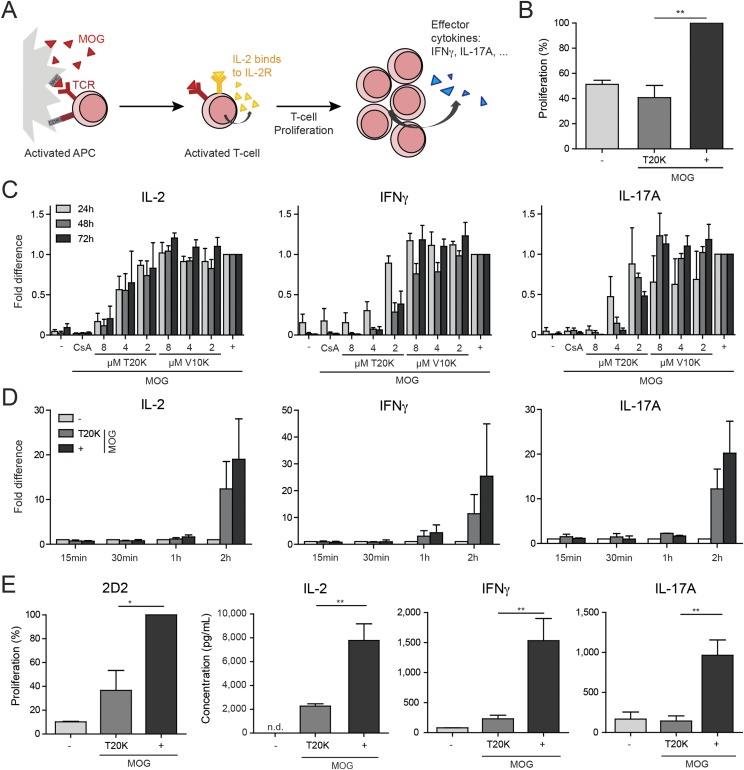

Fig. S2.

Cytokine response of EAE-induced or 2D2 isolated splenic T cells after MOG restimulation. (A) Restimulation scheme. EAE-induced antigen-presenting cells (APC) get activated in presence of MOG and stimulate T cells to secrete IL-2, which acts in an autocrine way to its IL-2 cell surface receptor (IL-2R) to induce proliferation and inflammatory cytokine response. (B) Proliferation was analyzed via flow cytometry measuring CFSE dilution of CD3-positive EAE-induced splenic T cells, incubated for 2 h with [T20K]kB1, restimulated (+) for 72 h with MOG (n = 3), and compared with nonstimulated cells (−). (C) Cytokine secretion from ex vivo MOG-restimulated splenic T cells of EAE-induced mice. Data (mean ± SEM) were normalized to the MOG control (n = 3) after treatment with [T20K]kB1, [V10K]kB1, and cyclosporine A (CsA, 5 µg/mL) and restimulation with MOG. (D) Quantification of cytokine-specific mRNA expression was performed by real-time PCR of splenic EAE T cells incubated for 2 h with [T20K]kB1 and restimulated with MOG for the indicated time period. Data (mean ± SEM) were normalized to HPRT (n = 4, except n = 2 for IFN-γ and IL-17A: 15 min, 30 min, 1 h). (E) In vitro treatment of genetically modified 2D2 splenocytes with cyclotides. Proliferation (percent) of splenic T cells from 2D2 mice incubated for 2 h with [T20K]kB1 and restimulated for 3 d with MOG was analyzed via flow cytometry measuring CFSE dilution (n = 3). IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A cytokine release of ex vivo MOG-restimulated (IL-2 48 h; IFN-γ and IL-17 72 h MOG stimulation) splenic T cells from 2D2 mice, after a preceding incubation for 2 h with [T20K]kB1 (measured by ELISA). Data illustrate mean ± SEM values of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A concentrations in picograms per milliliter (IL-2 n = 4, IFN-γ n = 3; IL-17A n = 2). Significance was calculated using Student’s t test, comparing indicated groups.

Activity and Therapeutic Effects of Cyclotides to Treat EAE.

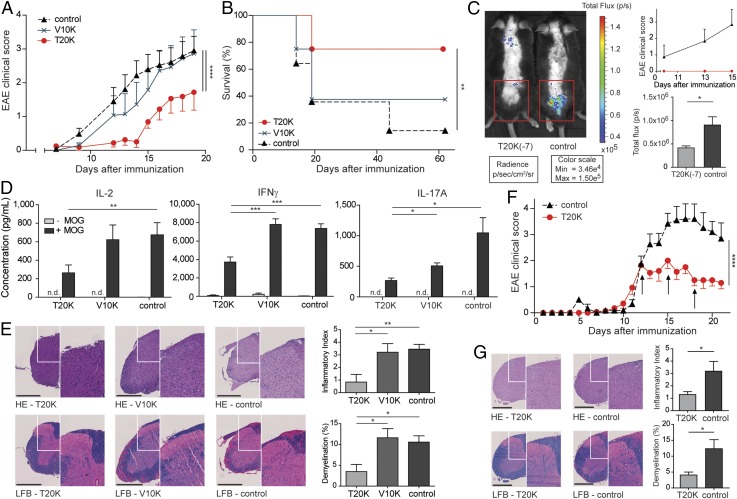

The cyclotide [T20K]kB1 exhibits concentration-dependent immunosuppressive activity in vitro, which encouraged the investigation of the in vivo activity of the circular plant peptide using the T-cell-specific EAE model. C57BL/6 mice immunized with MOG and treated in advance (day −7) i.p. with [T20K]kB1 (10 mg/kg) demonstrated a significant delay of the onset and only minor symptoms of the autoimmune encephalomyelitis, whereas the inactive mutant or the untreated control group exhibited no significant effects in disease reduction; these mice experienced severe bilateral paralysis and weight loss (Fig. 2A, Fig. S3A, Table S1, and Movie S1). Survival analysis of EAE experiments, including moribund mice (clinical score ≥4, see SI Materials and Methods), further supported the observation that treatment of EAE mice with the cyclotide [T20K]kB1 exerts long-lasting and protective T-cell antiproliferative properties (Fig. 2B). Using IVIS, a lower chemiluminescent signal based on the release of myeloperoxidase by inflammatory cells was detected in the appropriate regions in cyclotide-treated EAE-induced mice, compared with the untreated control group (Fig. 2C). Splenic T cells of EAE-induced mice enhance inflammatory cytokine expression when incubated with the antigen MOG. Isolation and MOG restimulation of splenocytes from cyclotide-pretreated mice exhibited a significant reduction of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A levels compared with both the [V10K]kB1-treated and untreated control group (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, no significant perivascular infiltration of mononuclear cells and an intact myelin sheath of the spinal cord of cyclotide-treated mice were observed using H&E and Klüver Barrera Luxol Fast Blue (LFB) stains. This explains the significant reduction of inflammation and lower grade of demyelination in the CNS (Fig. 2E). Taken together, [T20K]kB1 cyclotide treatment not only leads to halt of disease progression, but also induces long-lasting effects supporting survival and hindering restimulation of splenic T cells. Consequently, we evaluated the effects of a therapeutic treatment for reversion of autoimmune disease progression. C57BL/6 mice were treated with 10 mg/kg [T20K]kB1 1 wk before (day −7), at the day of immunization (day 0), and 1 wk after (day 7) (Table S1). Mice treated with the cyclotide revealed an inhibition or a delay in the progression of the autoimmune encephalomyelitis reliant on the time point of the treatment (Figs. S4A and S3B). This was confirmed by histological H&E and LFB stains, which showed increased inflammation and advanced demyelination induced by mononuclear cells infiltrating the spinal cord the later the cyclotide injection was performed. Thus, the highest degree of reduction of inflammation and the lowest grade of demyelination of axons was observed in [T20K]kB1- (day −7) treated mice (Fig. S4C). Proliferation-inducing IL-2 and other TH1- and TH17-related inflammatory cytokines were significantly reduced in MOG-restimulated isolated splenic T lymphocytes, influenced by the time point of cyclotide treatment (Fig. S4D). Following these promising protective properties of the cyclotide [T20K]kB1 against autoimmunity, EAE-induced mice were treated therapeutically at a score of 2, meaning at a disease stage of partial paraparesis. A pilot experiment with a single injection of cyclotide (10 mg/kg) resulted in a significant reduction in the clinical score (Figs. S4B and S3C), but effects on cytokine secretion were moderate (Fig. S4E). Nevertheless, treatment with three injections (10 mg/kg) administered every third day (Table S1) seemed to be more promising. The progression of the autoimmune encephalomyelitis was not only substantially blunted, but also the health status of the cyclotide-treated mice was slightly improved (Fig. 2F and Fig. S3D). In addition, autoimmune-related cytokine levels were reduced, suggesting a therapeutic potential of the nature-derived peptide [T20K]kB1 (Fig. S4F). These findings have been further verified by histological experiments that depicted an amelioration of the encephalomyelitis due to a lower grade of axonal demyelination in cyclotide-treated animals and decreased numbers of inflammatory cells in the CNS (Fig. 2G). In fact, cyclotide treatment resulted in a reduced number of CD3+ (P < 0.001) and CD4+ (P < 0.01) cells in the CNS and in decreased IL-2 release (P = 0.07) (Fig. S5).

Fig. 2.

Activity and therapeutic effect of cyclotides in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model. (A) Mean ± SEM. EAE clinical scores after administration at day −7 of [T20K]kB1 (red sphere), [V10K]kB1 (cyan cross), or untreated (black triangle, dashed line) MOG-immunized mice (n = 8; control: n = 14). Score 0, no signs; score 1, complete tail paralysis; score 2, partial paraparesis; score 3, severe paraparesis; score 4, tetraparesis; and score 5, moribund condition. Significance was determined by two-way ANOVA comparing indicated groups. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curve of day −7 treated [T20K]kB1, [V10K]kB1 or untreated MOG-immunized mice. Mice were euthanized reaching a score of 3.5–4. **P < 0.01 was determined by log rank test. (C) Chemiluminescence signal induced by bioluminescent substrate of [T20K]kB1-treated or untreated EAE mice monitored by IVIS on day 13 after MOG immunization, as shown in the clinical score diagram. Bar chart illustrates quantitative calculations of total flux (photons per second) using IVIS Living Image software [mean ± SEM ([T20K]kB1: n = 8; control: n = 7)]. (D) IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A cytokine release of ex vivo MOG-restimulated splenic T cells from cyclotide-treated and untreated MOG-immunized mice (measured by ELISA). Data illustrate mean ± SEM values of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A concentrations in picograms per milliliter. Significance was calculated using Student’s t test. (E) H&E and LFB spinal cord histology staining of [T20K]kB1 and [V10K]kB1 cyclotide-treated and untreated control EAE mice. Each image (white box) is illustrated with higher magnification (right side). Bar diagrams represent mean ± SEM of inflammatory index and percentage of demyelinated area of three cross-sections of each animal. (Scale bars: 500 µm.) (F) EAE clinical score (mean ± SEM) after therapeutic i.p. treatment of mice with cyclotides (three times in 3-d intervals, indicated by the arrows; [T20K]kB1: n = 7; control: n = 5). Statistical significance was analyzed using two-way ANOVA, from the first day of treatment. (G) H&E and LFB spinal cord histology staining of three times [T20K]kB1-treated or untreated EAE-induced mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

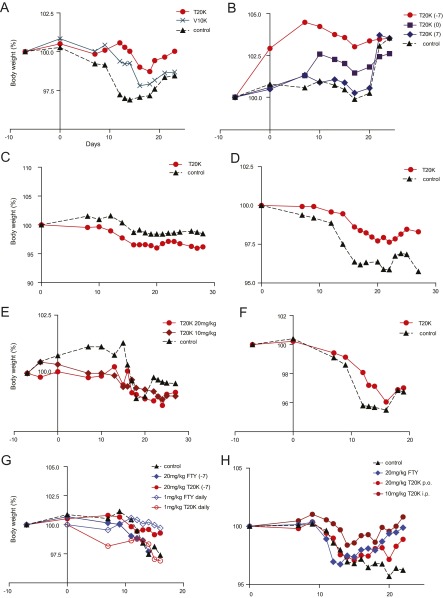

Fig. S3.

Body weight of EAE-induced and cyclotide-treated mice. Body weight of EAE-induced mice shown in percentage (100% represents the original weight at the beginning of the experiment). Day 0 was the day of MOG immunization. Body weight of mice treated (A) at day −7 with cyclotides (Fig. 2A); (B) a week before, a week after, and at the day of immunization (Fig. S4A); (C) one time (Fig. S4B); or (D) three times with 3-d intervals at a score of 2 with [T20K]kB1 i.p. (Fig. 2F), (E) orally (p.o.) with two different doses of the active cyclotide at day −7 (Fig. 3A), (F) orally at a score of 2 with 20 mg/kg three times, in 3-d intervals (Fig. 3B), (G) orally at day −7 or daily with [T20K]kB1 or fingolimod (FTY) (Fig. S9A), or (H) orally or i.p. three times at score 2 with [T20K]kB1 or FTY (Fig. S9B).

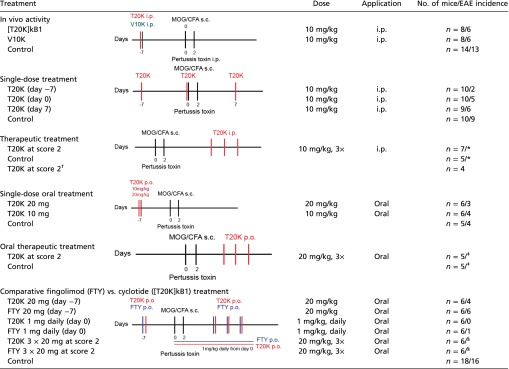

Table S1.

EAE immunization scheme and EAE incidence of individual experiments

|

Treatment protocol of EAE experiments representing application type, dose, and number of animals. Incidence illustrated number of mice developing an EAE clinical score higher than 1:*incidence: 20/19–12, score 2; ‡incidence: 12/10, score 2; §incidence: 12/12, score 2; †refer to control of fingolimod comparison.

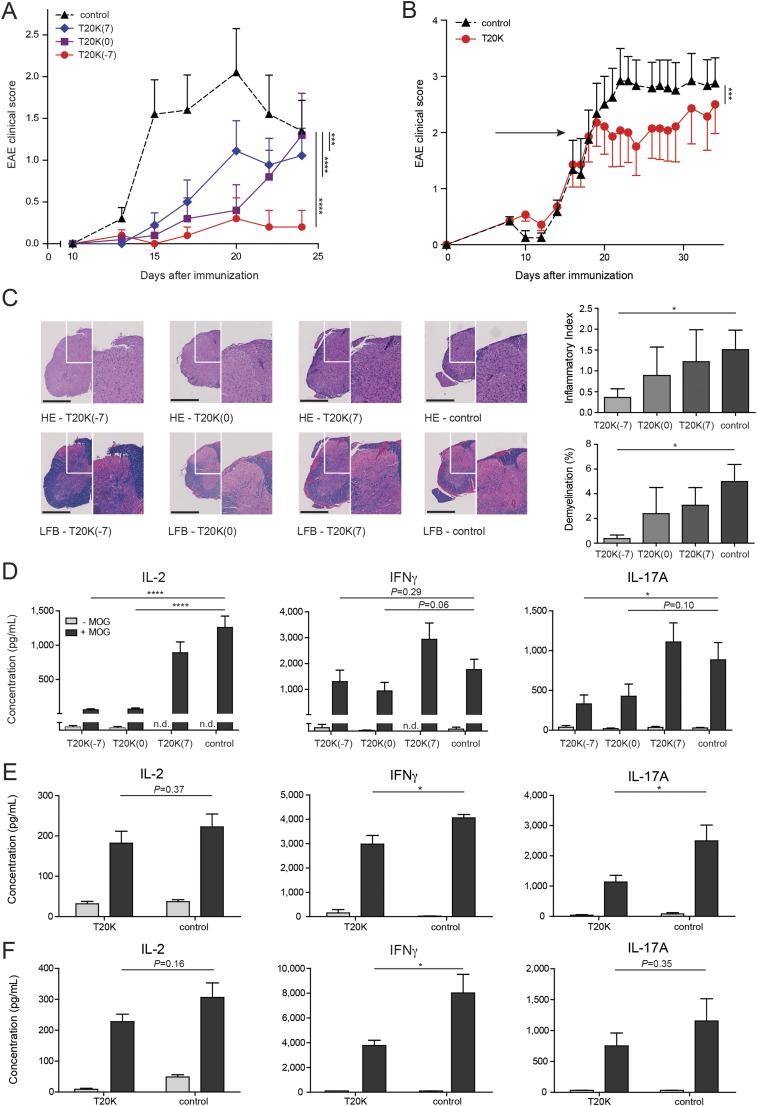

Fig. S4.

Activity and therapeutic effect of cyclotides. (A) EAE clinical disease score (mean ± SEM) of MOG-immunized mice [n = 10; T20K (day 7) n = 9] treated with [T20K]kB1 at day −7 (red sphere), day 0 (violet square), day 7 (blue diamond), or untreated control (black triangle, dashed line). (B) EAE clinical score of mice treated at a score of 2, once with 10 mg/kg [T20K]kB1 i.p. (red sphere, n = 7) or left untreated (control group; black triangle, dashed line; n = 6). Significance was determined by two-way ANOVA comparing indicated groups at the day of the treatment. (C) H&E and LFB staining of spinal cord sections from EAE-induced animals. Bar diagrams represent inflammatory index and percentage of demyelinated area. (Scale bars: 500 µm.) (D–F) Quantitative cytokine release of splenic T cells from indicated EAE mice after ex vivo ± MOG restimulation (ELISA). (D) Cytokine response from spleens isolated from mice treated at day −7, 0, or 7 with [T20K]kB1 (Fig. S4A); (E) from [T20K]kB1-treated and untreated MOG-immunized mice (Fig. S4B); (F) splenic T cells of three times i.p. treated mice (Fig. 2F). Data represent mean ± SEM values of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A cytokine concentrations in picograms per milliliter. Student’s t test was used to calculate significance (comparing indicated groups).

Fig. S5.

Effect of cyclotides on CNS T cells. (A) EAE clinical score (mean ± SEM) of mice treated i.p. at a score of 2 three times with 3-d intervals with 10 mg/kg [T20K]kB1 or left untreated (n = 4). (B) Quantification of CD3-, CD4-, or CD8-positive cells from the brain of cyclotide-treated or untreated mice (Fig. S5A) using flow cytometric analysis. (C) CD3 immunohistochemistry staining of spinal cord sections from EAE-induced animals (Fig. 2E). Each image (white box) is illustrated with higher magnification (right side). Bar diagrams represent number of counted CD3-positive cells. (Scale bars: 500 µm.) (D) Cytokine release (mean ± SEM values of IL-2 concentrations in picograms per milliliter) of CNS cells from indicated EAE mice (Fig. S5A) after ex vivo ± MOG restimulation (measured by ELISA). Student’s t test was used to calculate significance (comparing indicated groups).

Oral EAE Treatment Using the Cyclotide [T20K]kalata B1.

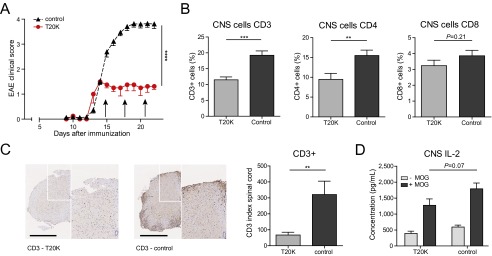

Because cyclotides are resistant against enzymatic and chemical degradation, due to their unique 3D structure, [T20K]kB1 was tested in an oral treatment experiment for its T-cell antiproliferative properties. Mice were treated with two different doses: one group of mice was given 10 mg/kg, the same dose as was used for the i.p. injections, and a second group was treated with 20 mg/kg (Table S1). Accordingly, [T20K]kB1 applied orally improved the EAE clinical score in a dose-dependent manner in comparison with the control group (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3E). The cumulative clinical score for the [T20K]kB1-treated mice (20 mg/kg) after oral administration (mean ± SEM: 21.5 ± 9.7) was significantly lower compared with the control group (64.1 ± 17.5), whereas treatment with a lower dose of [T20K]kB1 (10 mg/kg) was not significantly different (52.0 ± 24.2). Therefore, cytokine release of the 20 mg/kg [T20K]kB1 treatment was analyzed postrestimulation of splenic T cells after 48–72 h with their natural antigen MOG (Fig. S6A). These findings were substantiated with histology analysis, which revealed a minor inflammatory index and reduced areas of axonal demyelination in orally cyclotide-treated mice, compared with the EAE-induced control mice (Fig. S6B). Following up on those results, [T20K]kB1 was evaluated for its therapeutic application (Table S1). A significant amelioration of the autoimmune encephalomyelitis regarding the clinical score and histological analysis has been demonstrated by oral treatment using MOG-immunized mice (Fig. 3B and Figs. S3F and S6D). Mice treated three times with [T20K]kB1 at a score of 2 yielded a cumulative clinical score of 43.5 ± 12.3 compared with the control group, which exhibited 78.5 ± 10.7.

Fig. 3.

Oral activity and therapeutic properties of cyclotides. (A) Clinical EAE score (mean ± SEM) of orally [T20K]kB1-treated (day −7) mice with two different doses of 10 mg/kg (dark red diamond, n = 6) or 20 mg/kg (red sphere, n = 6) and untreated control group (black triangle, dotted line, n = 5). Two-way ANOVA was used to calculate statistical significance between [T20K]kB1-treated mice and the control group. (B) EAE clinical score (mean ± SEM) after therapeutic oral treatment of mice with [T20K]kB1 (20 mg/kg, three times in 3-d intervals, indicated by the arrows). [T20K]kB1: n = 5; control: n = 6. Statistical significance between cyclotide-treated and untreated EAE mice was analyzed by two-way ANOVA as of the first day of treatment. ****P < 0.0001.

Fig. S6.

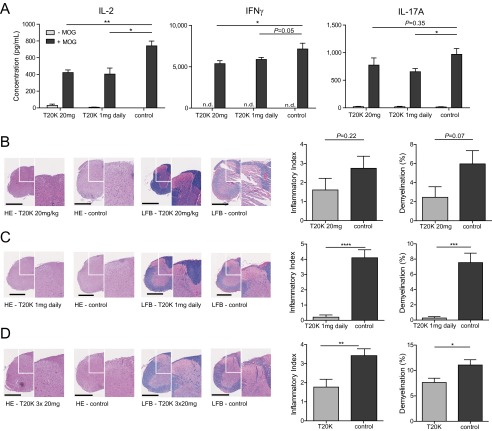

Oral activity and therapeutic properties of cyclotides. (A) Cytokine response of ex vivo MOG-restimulated splenic T cells from orally cyclotide-treated and untreated MOG-immunized mice measured by ELISA: restimulated for 48 h (IL-2) or for 72 h (IFN-γ and IL-17A) with MOG (Fig. S9A). Data illustrate mean ± SEM values of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A concentrations in picograms per milliliter. Significance was calculated using Student’s t test, comparing indicated groups. (B) Representative histological H&E and LFB images of spinal cord from orally cyclotide-treated or untreated MOG-immunized animals (n = 7) of two independent experiments (Fig. 3A and Fig. S9A). (C) H&E and LFB images of daily [T20K]kB1 (1 mg/kg; n = 5) treated or untreated (n = 3) EAE mice (Fig. S9A). (D) H&E and LFB images from three times orally cyclotide-treated (n = 7) and control (n = 10) animals (two independent experiments Fig. 3B and Fig. S9B). Each image (white box) is illustrated with higher magnification (right side). Bar diagrams represent inflammatory index and percentage of demyelinated area of three cross-sections of each animal. Statistical significance between cyclotide-treated and untreated EAE mice was analyzed using Student’s t test. (Scale bars: 500 µm.)

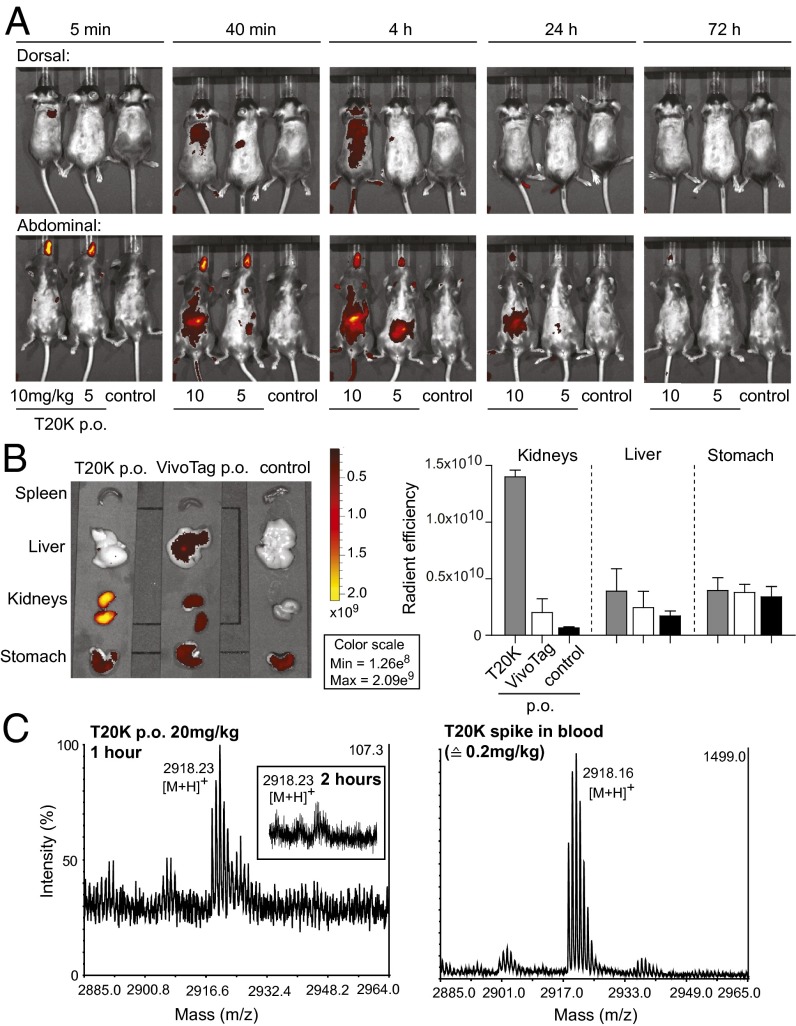

To analyze the biodistribution of cyclotides, [T20K]kB1 was labeled with the NIR-fluorescent VivoTag. After oral administration of the derivatized cyclotide, an uptake into the gastrointestinal tract, systemic distribution and excretion mainly via the renal/urinary tract was monitored, using the IVIS (Fig. 4A and Fig. S7). In comparison, the VivoTag label alone applied at the same concentrations exhibited less fluorescent intensity and a faster excretion. After 72 h mice were euthanized and the organs were screened for fluorescence signal. The labeled cyclotide exhibited a strong signal in the kidneys, compared with the label alone and control. Liver and spleen lacked any label-specific signal. However, animals treated with label alone showed a low degree of signal in kidneys and liver (Fig. 4B). Systemic uptake of the cyclotide was determined by mass spectrometry analysis of serum samples at 1 and 2 h postadministration, respectively (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Biodistribution and uptake of cyclotides after oral administration. (A) Biodistribution of orally applied VivoTag-labeled-[T20K]kB1, using two doses of 10 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg, and untreated control mice. Fluorescence intensity (radiant efficiency) was monitored using the IVIS at the indicated time points (5 min, 40 min, and 4, 24, and 72 h) after oral gavage from dorsal and abdominal directions. (B) Organs of orally treated mice with VivoTag-labeled [T20K]kB1 and VivoTag label alone and from untreated control mice were scanned for fluorescence intensity (radiant efficiency) using IVIS 72 h after compound administration. Calculation and quantification was performed using IVIS Living Image software, illustrating radiant efficiency of the kidneys, the liver, and the stomach of indicated animals. Data demonstrate mean ± SEM of two independent experiments. (C) Analysis of native [T20K]kB1 in serum samples after oral administration of 20 mg/kg peptide, 1 h (Left) and 2 h (Inset) postadministration, respectively, using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Control measurements of [T20K]kB1 spiked into fresh blood at 0.2 mg/kg corresponding to 1% of the total administered dose (Right). Peptide peaks are given as monoisotopic mass [M+H]+.

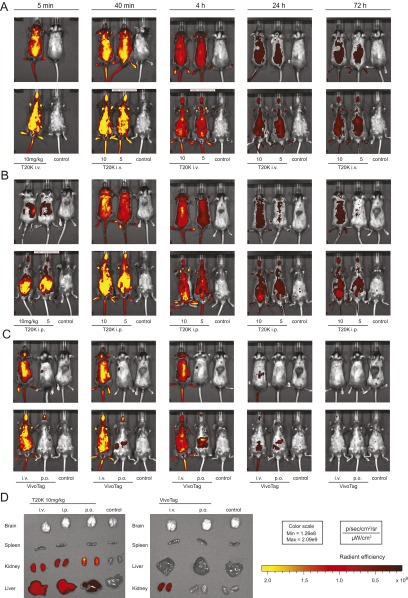

Fig. S7.

Biodistribution of VivoTag-labeled cyclotide. [T20K-VivoTag]kB1 (10 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg) was injected i.v. (A) or i.p. (B) into naïve mice. Biodistribution of the labeled peptide was monitored at indicated time points (5 min, 40 min, and 4, 24, and 72 h) by using the IVIS. (C) VivoTag alone was either applied i.v. or by oral gavage (p.o.) and monitored as described above. (D) After 72 h organs of euthanized [T20K-VivoTag]kB1 or VivoTag-alone treated mice were scanned for fluorescence intensity. Quantification was calculated using the IVIS Living Image software.

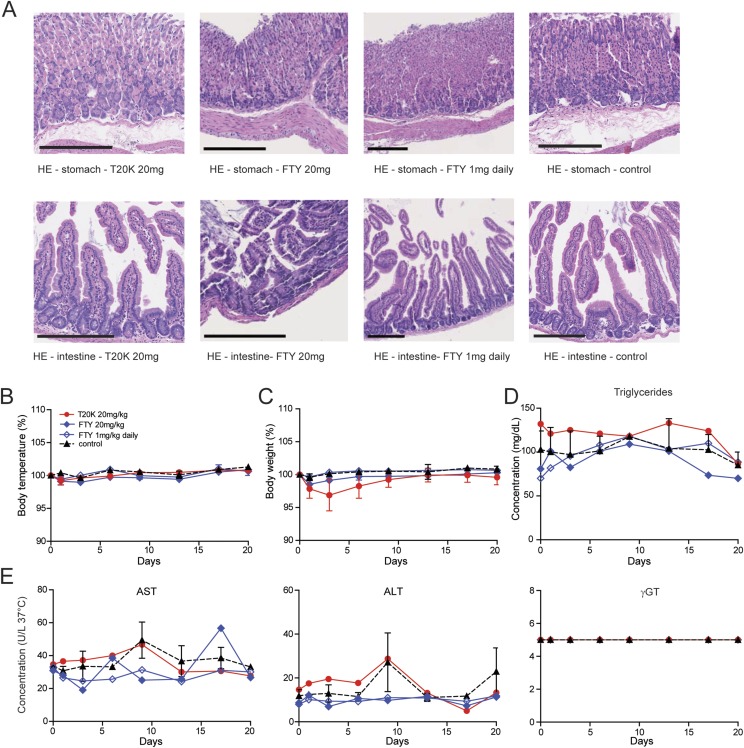

Owing to the stable body weight of treated mice, administration of up to three doses of 10 (i.p.) or 20 mg/kg (oral) of [T20K]kB1, respectively, seems to be safe. To confirm lack of adverse effects, liver toxicity was determined by measuring liver enzymes [i.e., aspartate (AST or GOT) and alanine transaminase (ALT or GPT)], which are markers for cellular integrity, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (γGT) as an indicator for disorders linked to the biliary tract. After oral application of 20 mg/kg of [T20K]kB1 in healthy mice, body weight and temperature as well as the liver parameters mentioned above were monitored and confirmed its safety. In addition, the concentration of the lipid parameters triglycerides and cholesterol indicated no difference between [T20K]kB1-treated mice and the control group. Histology of the gastrointestinal tract further confirmed that cyclotides do not cause cellular lesions or noticeable adverse effects after oral administration (Fig. S8).

Fig. S8.

Evaluation of biochemical and physiological parameters of mice after oral cyclotide treatment. (A) H&E histology staining of the stomach and the intestine of [T20K]kB1-treated (20 mg/kg, orally, p.o.), fingolimod (FTY, 20 mg/kg or daily 1 mg/kg, orally), and untreated control mice (naïve) (n = 3). (Scale bars: 200 µm.) (B) Body temperatures and (C) body weight in percent monitored at day 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 13, 17, and 20. Analysis of (D) lipid parameters (triglycerides) as well as (E) liver enzymes [i.e., aspartate (AST or GOT), alanine transaminase (ALT or GPT), and γGT] using the Reflotron Plus system at indicated time points.

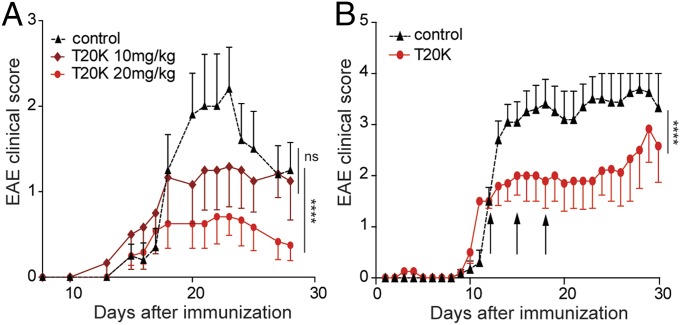

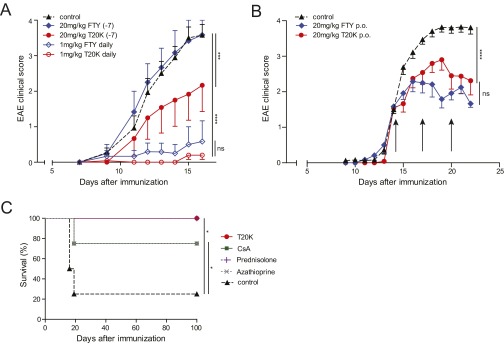

Furthermore, we carried out a head-to-head comparison of the circular plant peptide and the oral bioavailable drug fingolimod. The latter is being used in the clinic to treat MS and is therefore the appropriate reference. A single administration of 20 mg/kg fingolimod a week before (day −7) MOG immunization with 20 mg/kg did not mitigate the course of the disease: Clinical scores of fingolimod-treated and control animals were comparable. In contrast, the cyclotide ameliorated the subsequent course of the disease in a statistically significant manner (P < 0.001) (Fig. S9A and Table S1). Application of 20 mg/kg three times in 3-d intervals resulted in a reduction in EAE disease progression; the effect was comparable in magnitude for both fingolimod and the cyclotide (Fig. S9B). Daily administration (starting at day 0) of fingolimod at an established dose of 1 mg/kg (30) seemed to be the most effective treatment to halt progression of EAE. Similarly, the cyclotide [T20K]kB1 achieved comparable efficacy if animals were treated with a daily dose of 1 mg/kg (Fig. S9A). In fact, daily cyclotide treatment leads to a substantially reduced level of cytokine secretion (IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A), as well as a significantly lower degree of demyelination and a minor inflammatory index (Fig. S6C). No differences in adverse effects between the cyclotide (20 mg/kg) and fingolimod (20 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg daily) after oral administration can be observed using this animal study as determined by the same rigorous level of tolerability evaluation as described above (Fig. S8). Comparison of the cyclotide [T20K]kB1 to other immunosuppressant drugs revealed that morbidity and mortality (moribund mice) was significantly reduced in [T20K]kB1-, prednisolone-, azathioprine- and cyclosporine A-treated mice (Fig. S9C).

Fig. S9.

Comparison of different compounds for treatment of EAE. Clinical score (mean ± SEM) of EAE-induced mice, which received either [T20K]kB1 or fingolimod (FTY) at different doses (1; 20 mg/kg) and time points, that is, at day −7 and daily starting at day 0 (A) or three times at score 2 with 3-d intervals (B). Protocol for the FTY treatment schedule was adapted as described in the main text and modified according to cyclotide treatment experiments. (C) Survival analysis of EAE-induced animals treated with different immunosuppressive drugs or [T20K]kB1 (20 mg/kg orally at day −7). Statistical significance was calculated using a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test.

Discussion

Although preliminary studies have shown that the cyclotide kalata B1 can inhibit lymphocyte proliferation in vitro (12) the effectiveness of nature-derived cyclotides to prevent or treat autoimmune disorders in vivo after oral administration has hitherto not been reported. Our study demonstrates that the peptide [T20K]kB1 is an orally active therapeutic for treatment of the T-cell-mediated MS model EAE (22) in vivo.

Antiproliferative effects of the cyclotide kalata B1 and the mutant [T20K]kB1 have been investigated on human mononuclear cells and purified T cells, highlighting the IL-2–specific inhibitory mechanism in vitro (12, 13). Release of TH1 and TH17 signature cytokines were not only inhibited in vitro when incubated with the cyclotide, but also after ex vivo restimulation of EAE-induced [T20K]kB1-pretreated splenocytes with their natural antigen MOG. In particular, the reduction in the disease-relevant T-cell cytokine IL-17A supports the observed clinical and histological reversion of disease progression upon cyclotide treatment. Initially various treatment regimens confirmed in vivo activity to reduce EAE-associated symptoms of [T20K]kB1 by parenteral application (i.p.). Interestingly, in vivo activity of [T20K]kB1 was sequence-specific because the cyclotide [V10K]kB1 (or the untreated control group) exhibited neither significant effects in disease reduction nor any significant reduction of inflammation or demyelination in the CNS. An effective way to prevent an episode of EAE was administration of cyclotide to healthy mice 1 wk before disease induction. This could be an advantage in the relapsing–remitting form of MS, one of the most common types (31). After the decline of the first symptoms, cyclotide treatment could potentially interfere with the recurrence of more profound disabilities. In addition, daily treatment with lower doses seemed to be very efficient to prevent disease progression. However, [T20K]kB1 was also effective to treat mice at a disease stage of paraparesis, which impeded progression of EAE substantially.

To take advantage of the structural stability of cyclotides, the oral treatment experiments describe for the first time to our knowledge cyclotides used as oral active therapeutics for EAE. Administration of cyclotides at therapeutic doses did not induce adverse effects; it not only elicited a short-lived effect on the secretion of signature cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17A) but also maintained the health status of the cyclotide-treated mice. Application of cyclotide leads to reversion of disease progression and induces long-lasting effects supporting survival and hindering restimulation of splenic T cells. The observed inhibition on proliferation of splenocytes isolated from the genetically modified 2D2 mouse model further supports a strong beneficial effect on disease development.

Oral treatment required a higher dose compared with parenteral administration likely due to low bioavailability of [T20K]kB1, as commonly observed for peptide therapeutics (3). In fact, grafted cystine-knot peptides are thought to have limited bioavailability of less than 1%. Nevertheless, it was possible to detect traces of [T20K]kB1 in serum by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry up to 2 h following oral administration. The gastrointestinal uptake and systemic biodistribution of a derivatized cyclotide ([T20K-VivoTag]kB1) has been confirmed by IVIS. Although the VivoTag-labeled cyclotide may exhibit different physicochemical properties, IVIS seemed to be a valid model system to monitor the trajectory of the cyclotide following oral administration based on the known stability of cyclotides in proteolytic environment and at acidic conditions (32).

The long-term effect induced by the cyclotide [T20K]kB1 was comparable to known immunosuppressive drugs, such as cyclosporine A, prednisolone, and azathioprine, but their clinical use in MS therapy is limited due to low activity, lack of oral bioavailability, or high incidence of systemic side effects (33–35). In a head-to-head comparison of [T20K]kB1 and fingolimod, a recently approved orally bioavailable drug to prevent MS progression, the cyclotide seemed to be an advantageous therapeutic option when administered at a single dose; fingolimod was only effective with multiple administrations, and best at daily administration of its therapeutic dose. Consequently, cyclotides exhibiting oral activity are very promising acquisitions in drug discovery, not only regarding the treatment of MS but as a potential option for oral treatment of other autoimmune-related diseases (25, 36). Successful advances in chemical and recombinant synthesis (37, 38) as well as enzymatic folding (39) and cyclization (40) may yield affordable production of cyclotides at clinical scale in the near future.

At the more general level, our work provides a proof of principle for the concept that nature-derived cyclic peptides serve as oral active therapeutics using their intrinsic bioactivity and stable 3D structure. In fact, cyclotides have been recently used as scaffolds to improve the stability of peptides that have interesting pharmaceutical activities. This grafting introduced peptide sequences into cyclotide loops and resulted in a chimeric molecule that was orally active as bradykinin B1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of chronic inflammatory pain (18). Cyclotides represent a natural combinatorial peptide library and they probe a chemical space that is difficult to target by using small organic molecules (17). Thus, at the very least, they can be anticipated to complement the existing collections of natural products or synthetic molecules that are used in drug discovery. In particular, building on the unique topology of cyclotides (16) may complement efforts in rational design of bioavailable cyclic peptide therapeutics (41).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that documents that a ribosomally synthesized, plant-derived cyclic peptide is effective after oral administration to prevent and to treat EAE in mice, the gold-standard animal model of human multiple sclerosis (22). Incidentally, cyclosporine A produced by the fungus Tolypocladium inflatum is also a cyclic (undeca)peptide and it is considered the prototype of a new generation of immunosuppressive drugs (42). Historically, cyclosporine A was instrumental to the development of modern immunopharmacology and it is still in clinical use today (29, 36). Despite the limitations of such comparisons, we believe that the rich diversity of cyclotides (17, 43) justifies their position as a treasure trove for drug discovery.

Materials and Methods

Detailed materials and methods are given in SI Materials and Methods.

Peptide Synthesis.

Peptides were synthesized following a recent protocol for the generation of thioesterpeptides using Fmoc-SPPS and their use in native chemical ligation (26) and its adaptation for amino acid coupling assisted by microwave heating (27).

Animals and Ethics.

Eight-wk-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River and 2D2 myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein MOG35–55–specific TCR transgenic (tg) mice on a C57BL/6 background (C57BL/6-Tg[Tcra2D2,Tcrb2D2]1Kuch/J) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. All experiments were approved according to the European Community rules of animal care with the permission of the Austrian Ministry of Science (BMWF-66.009/0241-II/3B/2011).

EAE.

C57BL/6 mice were immunized at day 0 according to the protocol described recently in Sahin et al. (44). Progression of EAE was divided into five clinical stages: score 0, no signs; score 1, complete tail paralysis; score 2, partial paraparesis; score 3, severe paraparesis; score 4, tetraparesis; and score 5, moribund condition. Mice were euthanized by deeply anesthetizing them with ketamine reaching a score of 3–4 due to ethical guidelines.

In Vivo Imaging.

Cyclotide-treated (10 mg/kg i.p. on day −7) and untreated control EAE mice received RediJect D-Luciferin bioluminescent substrate (PerkinElmer) i.v. on day 12 after MOG immunization. Monitoring with the IVIS (PerkinElmer) was performed on day 13 by measuring chemiluminescence signal. Higher chemiluminescence levels represent enhanced inflammation in the appropriate regions. VivoTag 680 XL (PerkinElmer) labeled [T20K]kB1 was injected i.v., i.p., or orally (p.o.) into naïve mice. Fluorescence signal (excitation: 665 ± 5 nm, emission: 688 ± 5 nm) was monitored after indicated time points. Organs of euthanized mice were screened for the fluorescence and quantified by using IVIS Living Image software.

SI Materials and Methods

Peptide Synthesis.

Amino acid were purchased from Iris Biotech or PepChem as follows: Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH, Fmoc-Asn(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-Asp(OtBu)-OH, Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OH, Boc-Cys(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-Glu(OtBu)-OH, Fmoc-Gly-OH, Fmoc-Ile-OH, Fmoc-Leu-OH, Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH, Fmoc-Pro-OH, Fmoc-Ser(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-OH, Fmoc-Val-OH. O-(benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N0,N0-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) was from PepChem. N,N-dDimethylformamide (DMF) and dichloromethane (DCM) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), guanidine hydrochloride, reduced and oxidized glutathione, piperidine, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), triisopropylsilane (TIPS), 3,6-dioxa-1,8-octanedithiol, Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), 4-mercaptophenylacetic acid, α-cyano-hydroxy cinnamic acid, and 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate were from Sigma-Aldrich. Gel filtration PD-10 Sephadex G-25M columns were from GE Healthcare.

Synthesis followed a recent protocol for the generation of thioesterpeptides using Fmoc-SPPS and their use in native chemical ligation, and its adaptation to synthesize cyclotides assisted by microwave heating (according to references used in the main text). A rink type 3-(Fmoc-amino)-4-aminobenzoyl AM resin (Dawson’s DBz resin), 100–200 mesh, from Novabiochem (Merck-Millipore) with a substitution value of 0.49 mmol/g was used as starting point for the synthesis. Resin was allowed to swell in DMF for 2 h. The Fmoc protecting group was removed using 20% (vol/vol) piperidine solution in DMF two times for 5 min. Two equivalents of amino acid were dissolved in five equivalents of 0.5 M HBTU solution and activation was achieved by adding 10 equivalents of DIPEA base. The mixture was rigorously shaken for 1 min before added to the deprotected resin. The manual coupling of the first amino acid was repeated once. Afterward elongation of all other residues was performed on a Liberty1 microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM Corp.) applying an optimized microwave assisted Fmoc/HBTU SPPS protocol. The Nbz formation was performed using 4-nitrophenylchloroformate in DCM (16 equivalents based on the net weight gain after peptide synthesis). The acylation reaction was carried out at 23 °C for 1 h. Activation was achieved using 195 equivalents of DIPEA in DMF for 25 min at 23 °C. The Nbz-peptide was cleaved off the resin using TFA/TIPS/ddH2O 99.5/0.25/0.25% (vol/vol/vol) for 3 h at 23 °C. The released Nbz-peptide was precipitated with diethylether. Peptide precipitate was dissolved in 50% CH3CN/0.05% TFA in double-distilled H2O and lyophilized. The thioesterification was performed in a ligation buffer containing 200 mM mercapto-phenyl acetic acid, 20 mM TCEP, and 6 M guanidine-HCl in 200 mM phosphate solution adjusted to pH 7.0–7.2. Nbz-peptide was dissolved in the ligation buffer in 1 mM and the solution was stirred for 24 h. The cyclic peptide was purified from the ligation reagents using Sephadex G25 gel filtration columns. Peptide fractions were then lyophilized, before final purification of native cyclotide was achieved using preparative HPLC on a diChrom Kromasil C18 (250 × 20 mm, 10 µm) column (dichrom). Linear gradients from 5 to 80% solvent B [double-distilled H2O/CH3CN/TFA, 10/90/0.1% (vol/vol/vol), solvent A 0.1% TFA aqueous] was applied to achieve peptide separation. Quality control was judged upon A215 and A280 UV traces from an analytical C18 separation using a Phenomenex Kinetex (150 × 3 mm, 2.1 µm) column. Peptide purity ≥90% was accepted or otherwise submitted to another purification cycle.

Animals and Ethics.

Mice used for experiments and ethics permission for animal care have been described in the main text.

Genotyping.

Mice were earmarked 3 to 4 wk after birth. DNA from lysed (proteinase K lysis buffer) ear tissue was subjected to direct PCR using GoTaq Polymerase (Promega). Using the following 2D2 and control primers (Microsynth AG, Balgach, Switzerland) specific PCRs were performed: 2D2 forward: 5′-CCCGGGCAAGGCTCAGCCATGCTCCTG-3′, 2D2 reverse: 5′-GCGGCCGCAATTCCCAGAGACATCCCTCC-3′ and internal control primer forward: 5′-CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT-3′, reverse: 5′-GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATCATCC-3′.

EAE.

C57BL/6 mice of both sexes were used due to the fact that no sex-specific differences were registered. Mice were immunized at day 0 with 75 µL of equal amounts of MOG (MOG35–55, 1 mg/mL; Charite Berlin) and incomplete Freud’s adjuvants (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10 mg/mL Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco) s.c. into the left and right flank. Additionally mice received i.p. 200 ng pertussis toxin (Millipore,) solubilized in 100 µL PBS at day 0 and day 2. Mice were observed daily for clinical signs as described in the main text. C57BL/6 mice were immunized at day 0 according to the protocol described recently in Sahin et al. (44). Progression of EAE was divided into five clinical stages: score 0, no signs; score 1, complete tail paralysis; score 2, partial paraparesis; score 3, severe paraparesis; score 4, tetraparesis; and score 5, moribund condition. When a mouse meets exclusion criteria (score >4, loss of weight >20%, no water and food uptake, no grooming) then it is considered moribund. Mice were euthanized by deeply anesthetizing them with ketamine reaching a score of 3–4 due to ethical guidelines. Records were kept of animal numbers and treatment details; while scoring the operator was blinded to the treatment records. Two independent assistant operators performed random spot checks in a blinded manner to confirm the assessment of the main operator. This resulted in a blinded scoring procedure. For optimized effects in T-cell detection, histological assessments, and cytokine analysis following ex vivo restimulation it is critical to finalize the experiment at the disease peak. Survival analysis, including moribund mice, was performed using a Kaplan–Meier plot.

Histology.

Euthanized mice were perfused intracardiacally with PBS. Spinal cords were then isolated, fixed in 4% (vol/vol) buffered formalin, and processed for histological evaluation. Sections were stained with H&E and LFB using standard protocols. Furthermore sections were analyzed for CD3 surface expression using immunohistochemistry with rat-anti-CD3 (AbD Serotech) and goat-anti-rat (Vector Laboratories) antibodies. A minimum of three cross-sections of each animal were evaluated histologically. Inflammatory index was calculated as follows: The number of perivascular infiltrates in spinal cord cross-sections was divided by the number of used cross-sections for each animal. Therefore, a higher inflammatory index indicates more inflammatory infiltrates. To evaluate the extent of demyelinated area, total and demyelinated area of each cross section was measured in the KLB staining. The demyelinated area was then calculated and plotted as percent of total cross-section. Image J (NIH) was used for all histological evaluations. Stomach and intestine of euthanized mice were perfused with 10 mL PBS before fixation in 4% (vol/vol) buffered formalin. Gastrointestinal sections were stained with H&E and evaluated as described above.

In Vivo Imaging.

EAE-induced [T20K]kB1-treated (10 mg/kg i.p. on day −7) and untreated control EAE mice received RediJect D-Luciferin bioluminescent substrate (PerkinElmer) i.v. on day 12 after MOG immunization according to the manufacturers’ protocol. Monitoring with the IVIS (PerkinElmer) was performed on day 13 by measuring chemiluminescence signal, induced by the RediJect substrate. Higher chemiluminescence levels represent enhanced inflammation in the appropriate regions. Quantification was performed with Living Image software (PerkinElmer). VivoTag 680 XL (PerkinElmer) peptide was dissolved in 0.1 M NH4HCO3 buffer, pH 8.5. A 20-fold molar excess of labeling reagent was prepared in anhydrous DMSO and the reaction was allowed to proceed at 23 °C for 4 h. Reaction was stopped with 0.1% TFA. Purification of labeled peptide from excess of reagent was achieved by semipreparative HPLC using a diChrom Kromasil C18 column (250 × 10 mm, 5 µm) and linear gradients as indicated above. HPLC fractions were analyzed via MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in the negative reflector mode. Purity of peptide samples was determined to be ≥95% based on analytical HPLC and detection of VivoTag label in the A280 UV trace. Labeled [T20K]kB1 was injected intravenously, intraperitoneally, and per oral gavage into naïve mice. Fluorescence signal (excitation: 665 ± 5 nm, emission: 688 ± 5 nm) was monitored after 5 min, 20 min, 40 min, and 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 32, 48, 56, and 72 h. Organs (spleen, liver, kidney, stomach, and intestine) of euthanized mice were screened for the fluorescence and quantified by using IVIS Living Image software.

Serum Analysis.

Blood sampling was performed for indicated experiments. Sera were analyzed using the Reflotron Plus System (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Serum Uptake Analysis of Cyclotides After Oral Administration.

C57B1/6 mice were treated orally with 20 mg/kg [T20K]kB1 peptide and fresh blood was used for analysis of peptide in blood after 1 and 2 h postadministration. The total citrated blood (∼1.5 mL) was submitted to homogenization and cell lysis using the Precellyser 24 (Bertin Technologies). Proteins were removed using TCA precipitation with a final concentration of 10% (wt/vol) TCA. To enhance peptide recovery 45% (vol/vol) CH3CN (final) was added to the solution. The precipitation was allowed to proceed for 1.5 h at 4 °C and afterward proteins were pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was lyophilized and then dissolved in 100 µL 0.1% TFA (aqueous) and centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g before analysis. The samples were desalted and concentrated using ZipTips (Millipore). For mass spectrometry analysis a MALDI-TOF/TOF 4800 Analyzer was used (AB Sciex). The desalted samples (0.5 µL) were mixed with 6 µL of α-cyano-hydroxy cinnamic acid matrix, saturated in double-distilled H2O/CH3CN/TFA 50/50/0.1% (vol/vol/vol) and 0.5 µL were spotted onto a target plate and allowed to air-dry in the dark. External calibration was performed on a daily basis applying calibration mix 1 (Laserbiolabs). Mass spectra were recorded in the range of 2,500–3,500 Da with optimized settings for laser intensity number of shots per average spectrum and digitizer adjustment to obtain acceptable spectra. As a control measurement, the corresponding amount of 1% [T20K]kB1 of the total dose of 20 mg/kg was spiked into fresh blood. After 1 h of settling time at 4 °C the samples were processed accordingly as described above.

Splenocyte Isolation and Restimulation.

Spleens of euthanized mice were prepared in RPMI media (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FCS (Sigma-Aldrich), penicillin (100 U/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL; Sigma) on ice. To receive a homogeneous cell suspension, spleens were meshed through 40-µm nylon sieves and centrifuged for 5 min at 300 × g. The cell pellet was incubated for 1 min with 1 mL erythrocyte lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, pH 7.2–7.4). The reaction was stopped by addition of 10 mL full media and centrifugation for 5 min at 300 × g. Splenic cells (3 × 106/mL) were stimulated ex vivo with or without 30 µg/mL MOG for 48–72 h at 37 °C in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Treatment of splenocytes was performed according to the appropriate experiments, described in figure legends.

CNS T-Cell Isolation.

Immune cells were isolated from the CNS by digesting brain of appropriate animals with a mixture of 5 mL collagenase D (0.233 U/mg; Roche) and DNase I (Roche) (0.17 U/mL collagenase D and 0.01 mg/mL DNase I per organ). Brains were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a shaking incubator. For further disruption of the tissue EDTA (pH 8.0 in PBS) was added for a final concentration of 2 mM and suspension was pipetted up and down for 5 min at 23 °C before filtering through a 70-µm cell strainer. Cells were washed with PBS at 400 × g for 8 min at 4 °C before resuspension in RPMI media. Cells were used for FACS analysis or seeded at a concentration of 3 × 106/mL and stimulated ex vivo with 30 µg/mL MOG. Supernatants of stimulated cells were used for detection of cytokine secretion using an ELISA.

T-Cell Proliferation and Flow Cytometry.

Isolated T cells were incubated with 5 µM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; eBioscience) in PBS per 1 × 107 cells for 10 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding media containing 10% FCS. Cells were washed with media and incubated according to the appropriate protocols. Before analysis, cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse CD3, clone 17A2 (BioLegendsany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. FACS acquisition was performed on a BD canto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Further analysis was performed using BD FACSDIVA software (BD Biosciences). For quantification of CD3-, CD4-, and CD8-positive cells in the CNS, the following antibodies from eBioscience were used: CD3e (APC-eFluor780, 1465-2C11), CD4 (FITC, GK1.5), and CD8a (AF700, 53-6.7). Cells were incubated for 20 min at 4 °C on a shaker, before adding 150 µL FACS buffer to spin down at 500 × g for 3 min at 23 °C (brake low). After discarding supernatant, cells were resuspended in 100 µL FACS buffer supplemented with 7-AAD (1:40). Flow cytometric measurement (acquisition time: 60 s) was performed using a Gallios flow cytometer from Beckman Coulter. For analysis CXP and Kaluza software were used (Beckman Coulter).

ELISA.

To evaluate specific cytokine release of ex vivo stimulated splenocytes, antibodies and Ready-SET-Go! Cytokine ELISA kits were acquired from eBioscience and R&D Systems. Experiments were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured on the Synergy ELISA plate reader at 450 nm after colorimetric reaction of TMB 2 Component Microwell Peroxidase Substrate Kit from KPL (Medac) and 0.5 M H2SO4.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

RNA of pretreated cells was isolated via Qiagen RNA Isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantification of nucleic acid was determined by using Nanodrop (Peqlab). Five hundred nanograms of RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis following manufacturers’ instructions of High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Expression of mRNA was quantified by real-time PCR using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with the StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Levels of target genes were normalized to HPRT and described as fold increase of unstimulated control cells. The following primer (Microsynth AG) sequences were used: HPRT forward: 5′-CGCAGTCCCAGCGTCGTG-3′, HPRT reverse: 5′-CCATCTCCTTCATGACATCTCGAG-3′, IL-2 forward: 5′-TGCAACTCCTGTCTTGCATT-3′, IL-2 reverse: 5′-GCCTTCTTGGGCATGTAAAA-3′, IFN-γ forward: 5′-TGAGCTCATTGAATGCTTGG-3′, IFN-γ reverse: 5′-ACAGCAAGGCGAAAAAGGAT-3′, IL-17A forward: 5′-TGAGCTTCCCAGATCACAGA-3′, IL-17A reverse: 5′-TCCAGAAGGCCCTCAGACTA-3′.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical significance of data was calculated by use of GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software). Two-way ANOVA analyzes were used to analyze two groups over time. Two groups were compared by using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Survival was determined by log-rank test comparing indicated groups. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. The P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant and are expressed in the figures as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Craik (University of Queensland) and Bachem AG for supplying peptides for this research, Günther Lametschwandtner and Hannes Mühleisen (Apeiron Biologics AG) and Richard Clark (University of Queensland) for technical support, and Kjell Stenberg (Accequa AB) for comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by Austrian Science Fund Grant FWF-P24743, Austria Wirtschaftsservice GmbH Prize-P1308423, and Australian Research Council Future Fellowship FT140100730 (to C.W.G.). C.G. was financially supported by the Software AG Foundation and DAMUS-DONATA e.V.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: C.G. and C.W.G. serve as members of the scientific advisory board of Cyxone AB since January 25, 2016.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1519960113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Koehn FE, Carter GT. The evolving role of natural products in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(3):206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrd1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey AL, Edrada-Ebel R, Quinn RJ. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(2):111–129. doi: 10.1038/nrd4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craik DJ, Fairlie DP, Liras S, Price D. The future of peptide-based drugs. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2013;81(1):136–147. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaspar AA, Reichert JM. Future directions for peptide therapeutics development. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18(17-18):807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnison PG, et al. Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: Overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30(1):108–160. doi: 10.1039/c2np20085f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruber CW, Muttenthaler M, Freissmuth M. Ligand-based peptide design and combinatorial peptide libraries to target G protein-coupled receptors. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(28):3071–3088. doi: 10.2174/138161210793292474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivera BM, et al. Peptide neurotoxins from fish-hunting cone snails. Science. 1985;230(4732):1338–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.4071055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McIntosh M, Cruz LJ, Hunkapiller MW, Gray WR, Olivera BM. Isolation and structure of a peptide toxin from the marine snail Conus magus. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;218(1):329–334. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis RJ. Conotoxins: Molecular and therapeutic targets. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2009;46:45–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-87895-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar PS, Kumar DS, Umamaheswari S. A perspective on toxicology of Conus venom peptides. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015;8(5):337–351. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pope JE, Deer TR. Intrathecal pharmacology update: Novel dosing strategy for intrathecal monotherapy ziconotide on efficacy and sustainability. Neuromodulation. 2015;18(5):414–420. doi: 10.1111/ner.12274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundemann C, Koehbach J, Huber R, Gruber CW. Do plant cyclotides have potential as immunosuppressant peptides? J Nat Prod. 2012;75(2):167–174. doi: 10.1021/np200722w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grundemann C, et al. Cyclotides suppress human T-lymphocyte proliferation by an interleukin 2-dependent mechanism. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e68016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craik DJ. Plant cyclotides: Circular, knotted peptide toxins. Toxicon. 2001;39(12):1809–1813. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang YH, et al. Design of substrate-based BCR-ABL kinase inhibitors using the cyclotide scaffold. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12974. doi: 10.1038/srep12974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craik DJ, Swedberg JE, Mylne JS, Cemazar M. Cyclotides as a basis for drug design. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2012;7(3):179–194. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.661554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koehbach J, et al. Oxytocic plant cyclotides as templates for peptide G protein-coupled receptor ligand design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(52):21183–21188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311183110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong CT, et al. Orally active peptidic bradykinin B1 receptor antagonists engineered from a cyclotide scaffold for inflammatory pain treatment. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(23):5620–5624. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malek TR, Bayer AL. Tolerance, not immunity, crucially depends on IL-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(9):665–674. doi: 10.1038/nri1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langston PK, et al. Au-ACRAMTU-PEt3 alters redox balance to inhibit T cell proliferation and function. J Immunol. 2015;195(5):1984–1994. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickey WF. The pathology of multiple sclerosis: A historical perspective. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;98(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McFarland HF, Martin R. Multiple sclerosis: A complicated picture of autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):913–919. doi: 10.1038/ni1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Walt A, et al. Neuroprotection in multiple sclerosis: A therapeutic challenge for the next decade. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126(1):82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ransohoff RM, Hafler DA, Lucchinetti CF. Multiple sclerosis-a quiet revolution. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(3):134–142. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith AB, Daly NL, Craik DJ. Cyclotides: A patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2011;21(11):1657–1672. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.620606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanco-Canosa JB, Dawson PE. An efficient Fmoc-SPPS approach for the generation of thioester peptide precursors for use in native chemical ligation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47(36):6851–6855. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunasekera S, Aboye TL, Madian WA, El-Seedi HR, Goransson U. Making ends meet: Microwave-accelerated synthesis of cyclic and disulfide rich proteins via in situ thioesterification and native chemical ligation. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2013;19(1):43–54. doi: 10.1007/s10989-012-9331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fletcher JM, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Tubridy N, Mills KH. T cells in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiber SL. Chemistry and biology of the immunophilins and their immunosuppressive ligands. Science. 1991;251(4991):283–287. doi: 10.1126/science.1702904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kataoka H, et al. FTY720, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator, ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibition of T cell infiltration. Cell Mol Immunol. 2005;2(6):439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lublin FD, et al. Management of patients receiving interferon beta-1b for multiple sclerosis: Report of a consensus conference. Neurology. 1996;46(1):12–18. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang CK, et al. Molecular grafting onto a stable framework yields novel cyclic peptides for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9(1):156–163. doi: 10.1021/cb400548s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allison AC. Immunosuppressive drugs: The first 50 years and a glance forward. Immunopharmacology. 2000;47(2-3):63–83. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: From biology to therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(11):839–855. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Getts DR, et al. Current landscape for T-cell targeting in autoimmunity and transplantation. Immunotherapy. 2011;3(7):853–870. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thell K, Hellinger R, Schabbauer G, Gruber CW. Immunosuppressive peptides and their therapeutic applications. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19(5):645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheneval O, et al. Fmoc-based synthesis of disulfide-rich cyclic peptides. J Org Chem. 2014;79(12):5538–5544. doi: 10.1021/jo500699m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimura RH, Tran AT, Camarero JA. Biosynthesis of the cyclotide Kalata B1 by using protein splicing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45(6):973–976. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gruber CW, et al. A novel plant protein-disulfide isomerase involved in the oxidative folding of cystine knot defense proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(28):20435–20446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris KS, et al. Efficient backbone cyclization of linear peptides by a recombinant asparaginyl endopeptidase. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10199. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang CK, et al. Rational design and synthesis of an orally bioavailable peptide guided by NMR amide temperature coefficients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(49):17504–17509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417611111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borel JF, Feurer C, Gubler HU, Stahelin H. Biological effects of cyclosporin A: A new antilymphocytic agent. Agents Actions. 1976;6(4):468–475. doi: 10.1007/BF01973261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hellinger R, et al. Peptidomics of circular cysteine-rich plant peptides: Analysis of the diversity of cyclotides from Viola tricolor by transcriptome and proteome mining. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(11):4851–4862. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahin E, et al. Macrophage PTEN regulates expression and secretion of arginase I modulating innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2014;193(4):1717–1727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.