Abstract

BACKGROUND

Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) are leading causes of transfusion-related mortality. Notably, poor syndrome recognition and underreporting likely result in an underestimate of their true attributable burden. We aimed to develop accurate electronic health record–based screening algorithms for improved detection of TRALI/transfused acute lung injury (ALI) and TACO.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

This was a retrospective observational study. The study cohort, identified from a previous National Institutes of Health–sponsored prospective investigation, included 223 transfused patients with TRALI, transfused ALI, TACO, or complication-free controls. Optimal case detection algorithms were identified using classification and regression tree (CART) analyses. Algorithm performance was evaluated with sensitivities, specificities, likelihood ratios, and overall misclassification rates.

RESULTS

For TRALI/transfused ALI detection, CART analysis achieved a sensitivity and specificity of 83.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 74.4%–90.4%) and 89.7% (95% CI, 80.3%–95.2%), respectively. For TACO, the sensitivity and specificity were 86.5% (95% CI, 73.6%–94.0%) and 92.3% (95% CI, 83.4%–96.8%), respectively. Reduced PaO2/FiO2 ratios and the acquisition of posttransfusion chest radiographs were the primary determinants of case versus control status for both syndromes. Of true-positive cases identified using the screening algorithms (TRALI/transfused ALI, n = 78; TACO, n = 45), only 11 (14.1%) and five (11.1%) were reported to the blood bank by physicians, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Electronic screening algorithms have shown good sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients with TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO at our institution. This supports the notion that active electronic surveillance may improve case identification, thereby providing a more accurate understanding of TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO epidemiology.

Blood product transfusions have long been recognized as an important risk factor for acute lung injury (ALI), with transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) consistently accounting for the greatest number of transfusion-related fatalities in the developed world.1,2 More recently, a second transfusion-related respiratory complication termed transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) has surpassed hemolytic transfusions reactions to become the second most common cause of transfusion-associated death.2 In 2010, TRALI accounted for 45% of all fatalities reported to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Meanwhile, in the same fiscal year, TACO accounted for 20% of reported fatalities, a figure that increased sharply between 2008 and 2009.2

Importantly, standardized definitions for TRALI and TACO have only recently been endorsed (Table 1).3,4 These definitions also outline a third group termed “possible TRALI” or “transfused ALI”5 for those patients whom meet the TRALI criteria in the presence of an alternate ALI risk factor. Moreover, current reporting systems for transfusion-related complications rely almost exclusively on bedside clinician’s case recognition skills and passive reporting mechanisms. In light of these issues, it is likely that current epidemiologic descriptions of TRALI and TACO are incomplete and biased toward recognition of only the most severe cases. Indeed, recent reports from Kopko and colleagues6 and Narick and colleagues7 validate these concerns for TRALI and TACO, respectively. As a result of these limitations, an accurate picture of TRALI and TACO epidemiology is lacking and the true attributable burden of these transfusion-related pulmonary complications remains unclear. Additionally, the delay or potential absence of case recognition may also negatively impact the outcome of transfusion recipients.8,9

TABLE 1.

TRALI and TACO case definitions

| NHLBI working group definition of TRALI | TACO Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition |

|---|---|

1. In patients without alternate ALI risk factors

|

New onset or exacerbation of at least three of the following within 6 hr of transfusion:

|

In the presence of an alternate ALI risk factor, patients are referred to as transfused ALI (also known as possible TRALI) in this study.

NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; PAOP = pulmonary artery occlusion pressure.

The implementation of electronic health records (EHRs) into the clinical environment affords an opportunity for highly efficient and scalable data extraction techniques. Moreover, the availability of these novel data extraction strategies may permit active surveillance of clinical diagnoses and syndromes of interest in a scalable manner. In light of the significance of TRALI and TACO in terms of transfusion recipient outcomes, as well as the recent availability of highly innovative electronic data capture strategies, we aimed to develop sensitive and specific automated electronic phenotypic screening algorithms to identify the transfusion-related pulmonary complications TRALI, transfused ALI, and TACO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approval, we conducted a retrospective cohort study evaluating patients with TRALI, transfused ALI, TACO, or a control group designation.

Study population

The study population was identified from a previous multicenter, National Institutes of Health–sponsored prospective cohort investigation that aimed to accurately define the incidence of TRALI.5 Details of this original study population have been previously reported.5 Briefly, the study population included all patients who were transfused at two tertiary care medical centers (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; and the University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) during their hospital stay between March 1, 2006, and August 31, 2009, provided permission to use their medical record had been granted. Patient’s less than 6 months of age were excluded. All transfused patients underwent active surveillance for evidence of respiratory decompensation in the 12-hour interval after blood product issue. Transfusion recipients with evidence of respiratory compromise were then formally evaluated for a diagnosis of TRALI, transfused ALI, or TACO (see outcome adjudication below). Control subjects were randomly selected transfusion recipients with no evidence of respiratory compromise in the 12-hour period after blood product issue. Control subject sampling was stratified by number of units transfused (regardless of component type): low (1–2 units), medium (3–9 units), and high volume (≥10 transfusions).

For the present investigation, a subset of this multi-center cohort was identified. Specifically, we included all of the Mayo Clinic study participants who had been allocated a TRALI, transfused ALI, TACO, or control status. A small number of these patients were excluded from our study due to an inability to identify an accurate transfusion time (n = 21) and for two cases duplicate appearance in the data set (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mayo Clinic transfusion recipient flow diagram.*Transfusion episode was defined as transfusion during 24-hour period. DAH = diffuse alveolar hemorrhage; ILD = interstitial lung disease. TACO/TRALI = adjudicated as definite transfusion-related pulmonary reaction in initial study; however, experts could not be certain whether this was TACO, TRALI, or a combination of both.

Outcome adjudication

Details relating to the procedures used for TRALI, transfused ALI, and TACO adjudication in the initial study have been previously described.5 Briefly, study personnel in the initial study were alerted to potential TRALI or TACO cases if transfused patients developed hypoxemia within 12 hours of blood product issue (Table 2). If a chest radiograph (CXR) was also available in the medical records, the radiologist report was reviewed by study personnel, and if bilateral infiltrates or opacities were reported, then these patients were considered “screen positive.” To maximize case detection in the event of a missed electronic alert, suspected cases were also reported to the research team by the responsible clinical team and/or the blood bank. Exclusion criteria are shown in Fig. 1. All screen-positive patients were then manually reviewed and a final diagnosis of TRALI, transfused ALI (also referred to as possible TRALI), or TACO was independently allocated by two expert reviewers based on the National Healthcare Safety Network definition of TACO4 and the 2005 NHBLI Working Group definition of TRALI.10 Of note, this TRALI definition bears close resemblance to the 2004 Canadian Consensus Criteria definition,3 but also considers patients with a major ALI risk factor as TRALI (as opposed to transfused ALI) if the clinical deterioration appeared to be temporally related to the onset of transfusion. Disagreements between the two expert reviewers were resolved by a third senior expert, who adjudicated the final diagnosis. Inter-observer agreement, assessed with kappa statistics, was 0.58 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.72) for the determination of TRALI versus all other diagnoses (TACO included) and 0.54 (95% CI, 0.40–0.68) for distinguishing TACO from all other diagnoses (TRALI and transfused ALI included). For the purposes of this study, we grouped TRALI and transfused ALI together as an outcome due to the fact that both conditions present in a similar manner with similar physiologic alterations. As a result, it is generally difficult to differentiate the two using automated EHR screening algorithms.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of previous versus new screening algorithm criteria

| Surveillance | TRALI SCCOR study5 | Our TRALI CART algorithm | Our TACO CART algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study subjects | |||

| Blood product issued | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age > 6 months | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Electronic screening data points | |||

| P : F ratio | <300 mmHg within 12 hr* | ≤288 mmHg within 8 hr* | ≤292 mmHg within 8 hr* |

| SpO2 | <97% | ≤97% | ≤96% |

| PaO2 | Not considered | ≤117 mmHg | ≤130 mmHg |

| RR | Not considered | Not considered | ≥17/min |

| CXR | Bilateral infiltrates or edema | Ordered within 8 hr* | Ordered within 8 hr* |

After blood product issue time.

SCCOR = Specialized Center of Clinically Oriented Research.

Identification of screening variables

For this study, potentially relevant electronic data that could be used to facilitate the identification of patients experiencing a possible transfusion-related pulmonary complication were identified from the literature11 and from the aforementioned broadly endorsed syndrome definitions.3,4,10 These data elements fell into four major assessment categories:

Oxygenation—partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2), PaO2 : fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio (P : F ratio), and oxygen saturation (SpO2).

Ventilation/work of breathing—respiratory rate (RR) and partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide(PaCO2).

Cardiovascular status—systolic blood pressure (SBP), heart rate (HR), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels.

Fluid status—diuretic administration, fluid balance, central venous pressure (CVP), and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) measurements.

All variables except fluid balance, BNP level, and diuretic administration were evaluated over the 8-hour interval after blood product issue. Blood product issue time was used as opposed to specific transfusion time as the latter was not available for all transfusion recipients. We considered that using data within an 8-hour window after blood product issue would most likely represent data within 6 hours of actual transfusion time, in keeping with the standard TRALI and TACO definitions. Fluid balance was assessed over the 24-hour interval preceding blood product issue and was calculated electronically by summing all fluid inputs and outputs recorded in the EHR during the 24-hour time frame for each patient. BNP level was assessed over the 24-hour interval after transfusion and diuretic administration was evaluated during the 6-hour interval preceding and the 6-hour interval after blood product issue. We also evaluated all CXRs within 8 hours of blood product issue.

Algorithm design

Two distinct methods were developed and evaluated for case detection. In the first, existing definitions for hypoxemia (e.g., P:F ratio < 300 mmHg, SpO2 < 90%, PaO2 < 60 mmHg), increased work of breathing (RR > 20/min, PaCO2 < 32 mmHg), and cardiovascular instability (Δ SBP > 20%, Δ HR > 20%), and fluid overload (CVP > 12 mmHg, PCWP > 18 mmHg, pretransfusion fluid balance ≥ 1500 mL) were utilized to design algorithms and determine significant thresholds. These data were supplemented with information regarding CXR acquisition, BNP concentrations, and diuretic administration. The TRALI/transfused ALI screening algorithm considered patients to be screen positive if the following criteria were met:

-

A CXR was obtained within 8 hours of transfusion (reflecting physician concern regarding respiratory compromise).

AND

Hypoxemic respiratory insufficiency was present as evidenced by a SpO2 < 90%, P : F ratio < 300 mmHg, or PaO2 < 60 mmHg.

The TACO screening algorithm considered transfusion recipients screen positive if the following criteria were satisfied:

-

Hypoxemia (evidenced by a SpO2 < 90%, P : F ratio < 300 mmHg, or PaO2 < 60 mmHg).

AND

-

Dyspnea (evidenced by a RR > 20/min or a PaCO2 < 32 mmHg).

OR

Hemodynamic instability (evidenced by a 20% increase in SBP or HR compared to baseline pre-transfusion values).

AND

-

Evidence of volume overload, manifest as one or more of the following:

CVP > 12 mmHg;

PCWP > 18 mmHg;

Fluid balance ≥ 1500 mL positive;

CXR obtained within 8 hours of blood product issue;

Diuretic administration.

As a secondary analysis we evaluated the accuracy of the TACO screening algorithm for distinguishing any transfusion-related pulmonary complication (TRALI/transfused ALI or TACO) from controls.

The second method for case identification utilized classification and regression tree (CART) analysis to define the algorithm variables and cut points. CART is a nonparametric decision tree learning technique that produces classification or regression trees, depending on whether the outcome variable is categorical or continuous, respectively. Decision trees are formed by a collection of rules based on the specific variables included in the modeling data set. These rules are determined and selected to get the best split to differentiate cases from controls. Once a rule is selected and splits a “parent” node into two, the same process is applied to each of the “child” nodes. Splitting stops when CART detects no further gain can be made with additional splitting procedures. Each branch of the tree ends in a terminal node and with each patient falling into one and only one terminal node. If minimal gain has been achieved with the splitting of a parent node, the classification/regression tree can be “pruned” to reduce the algorithm’s complexity.

Data sources and data management

The representative patient data were extracted from two independent electronic databases (the Mayo Clinic intensive care unit [ICU] data mart12 and the Mayo Clinic Life Science System13). These integrative databases gather clinical, laboratory, and radiographic data from various source databases and allow automated electronic algorithms such as those described in the present investigation to be applied. The validity and reliability of these systems have been previously described.14,15 Upon extracting the pertinent information from these two primary data sources, the data were then cleaned and stored using data management software (JMP, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Statistical analysis

To assess the accuracy of the algorithms developed in this investigation, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios (PLR and NLR) were determined. To further characterize the accuracy of these screening techniques, CART-associated misclassification rates were also determined. The size of the effect for each variable selected using the CART analysis was evaluated using multiple variable logistic regression analysis whereby selected variables were modeled against the outcome of interest (TRALI/transfused ALI, TACO, and the combined outcome of any transfusion-related pulmonary complication). Effect size estimates were represented as odds ratios (ORs) with associated 95% CIs. Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the impact of the transfusion environment (ICU, operating room, and general hospital wards) on the performance of the screening algorithms. As an additional secondary analysis, the number of true-positive screening results for TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO were compared with the number of cases reported to the blood bank through the current passive reporting system. All statistical analyses were performed with computer software (SAS, Version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Inc.).

RESULTS

With the methods described above, 223 patients were identified for inclusion in this study (36 TRALI, 57 transfused ALI, 52 TACO, and 78 controls). A recruitment flow diagram can be seen in Fig. 1. The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 3. Notably, there were significantly fewer males in the TACO group as well as significantly fewer TACO patients transfused in the general hospital ward environment. These differences are unlikely to be of clinical importance and are in keeping with previous literature suggesting that the greatest density of transfusion reactions occur in monitored environments such as the operating room and ICU, where the majority of blood product transfusions take place.16 Other significant differences were higher APACHE II scores in both the TACO and TRALI groups, a higher incidence of sepsis in the TRALI group, and more extreme deviation of hemodynamic and oxygenation variables from normal range in the TRALI and TACO groups when compared with transfused controls. These differences are expected and reflect the presence and severity of each respective transfusion-related pulmonary complication.

TABLE 3.

Patient characteristics*

| Variable | TRALI/transfused ALI (n = 93) | TACO (n = 52) | Transfused controls (n = 78) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 63 (52–71.5) | 67 (58.5–79) | 65 (49.5–75) | 0.1430 |

| Male sex | 45 (48.39) | 21 (40.38) | 51 (65.38) | 0.0111 |

| Transfusion environment | 0.0001 | |||

| Floor | 18 (19.35) | 2 (3.85) | 28 (35.90) | |

| ICU | 37 (39.78) | 13 (25) | 21 (26.92) | |

| Operating room | 38 (40.86) | 37 (71.15) | 29 (37.18) | |

| Race | 0.0887 | |||

| White | 83 (90.22) | 42 (80.77) | 69 (88.46) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 (3.26) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.28) | |

| Black/African American | 2 (2.17) | 2 (3.85) | 0 | |

| Asian | 0 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.28) | |

| Unknown | 5 (5.38) | 8 (15.38) | 7 (8.97) | |

| Blood group | 0.8209 | |||

| A | 40 (43.01) | 18 (34.62) | 36 (46.15) | |

| B | 11 (11.83) | 10 (19.23) | 10 (12.82) | |

| O | 38 (40.86) | 22 (42.31) | 28 (35.90) | |

| AB | 4 (4.30) | 2 (3.85) | 4 (5.13) | |

| Median APACHE II score | 13 (7–16) | 11 (8–14) | 9.5 (6–13) | 0.0234 |

| Blood products transfused (units) | 3.5 (2–7.5) | 4 (2–10.75) | 4 (3–10) | 0.4084 |

| Platelets transfused (units) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 0.3272 |

| RBCs transfused (units) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–5) | 0.1699 |

| Plasma transfused (units) | 4 (2–6) | 4 (2–6) | 4 (2.5–5) | 0.9343 |

| Cryoprecipitate transfused (units) | 2 (2–3.25) | 4 (2–4) | 2 (2–2) | 0.0825 |

| Smoking status | 0.0625 | |||

| Never | 40 (43.01) | 22 (42.31) | 43 (55.13) | |

| Former | 30 (32.26) | 23 (44.23) | 27 (34.62) | |

| Current | 18 (19.35) | 6 (11.54) | 8 (10.62) | |

| Unknown | 5 (5.38) | 1 (1.92) | 0 (0) | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.6044 | |||

| Yes | 9 (9.68) | 3 (5.77) | 5 (6.41) | |

| No | 80 (86.02) | 48 (92.31) | 72 (92.31) | |

| Unknown | 4 (4.30) | 1 (1.92) | 1 (1.28) | |

| Aspiration | 1 (1.08) | 0 (0) | 0 (0%) | 0.8149 |

| Sepsis | 17 (18.28) | 1 (1.92) | 3 (3.85) | 0.0042 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.1381 | |||

| Yes | 26 (27.96) | 17 (32.69) | 13 (16.67) | |

| No | 66 (70.97) | 35 (67.31) | 65 (83.33) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.08) | 0 | 0 (0) | |

| COPD | 7 (7.53) | 8 (15.38) | 4 (5.13) | 0.1327 |

| Cancer or chemotherapy | 23 (24.73) | 8 (15.38) | 19 (24.36) | 0.3574 |

| Lowest SpO2 | 87 (74–91) | 87 (81–92) | 93 (90–96) | 0.001 |

| Lowest P : F ratio (mmHg) | 97 (64–141) | 162 (72–230) | 352 (316–376) | 0.001 |

| Lowest PaO2 (mmHg) | 62 (50–86) | 78 (56–110) | 138 (100–167) | 0.001 |

| CXR obtained | 80 (86) | 45 (87) | 20 (26) | 0.001 |

| Δ Blood pressure (mmHg) | 49 (30–71) | 60 (27–76) | 27 (10–51) | 0.001 |

| Δ HR (bpm) | 30 (13–66) | 40 (21–94) | 14 (6–25) | 0.001 |

| Highest RR (/min) | 32 (27–40) | 30 (25–37) | 22 (20–26) | 0.001 |

| Lowest PaCO2 (mmHg) | 35 (30–41) | 35 (32–40) | 35 (32–41) | 0.7323 |

| Diuretics administered | 15 (16) | 23 (44) | 7 (9) | 0.001 |

| Highest CVP (mmHg) | 24 (15–36) | 23 (15–44) | 21 (14–36) | 0.9841 |

| Highest PCWP (mmHg) | 31 (25–36) | 34 (30–38) | 24 (22–26) | 0.0037 |

| Fluid balance (mL, 24 hr before Tx) | 2047 (700–4116) | 1400 (236–3471) | 1294 (745–2733) | 0.2132 |

Data are reported as number (%) or median (25%–75% interquartile range).

APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Tx = transfusion.

TRALI/transfused ALI screening algorithms

Of the 223 total study participants, 171 (n = 36 TRALI, 57 transfused ALI, 78 controls) were included in the development and testing of the TRALI screening algorithms. With the initial method which utilized existing definitions for determining algorithm cut points, 90 patients were identified as screen positive for TRALI or transfused ALI. Of these 90 patients, 29 of the 36 TRALI patients (80.6%) and 51 of the 57 (89.5%) transfused ALI patients were correctly identified. There were 10 false-positive results. The sensitivity and specificity of this algorithm were 86.0 (95% CI, 76.9%–92.1%) and 87.2% (95% CI, 77.2%–93.3%), respectively. The overall misclassification rate was 13.5%.

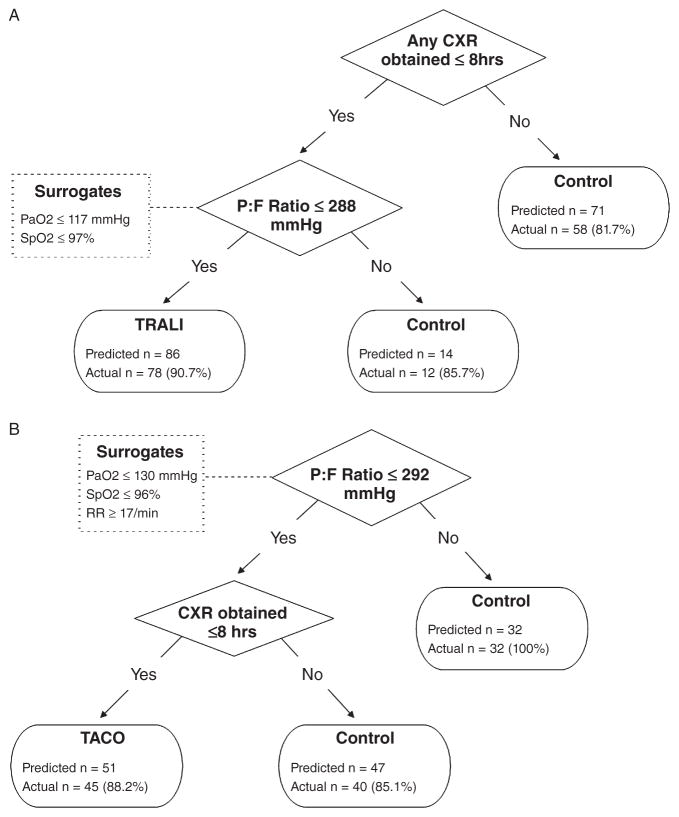

The modified screening algorithm resulting from the CART analysis can be seen in Fig. 2A. In this analysis, the best predictors of TRALI/transfused ALI were the presence of any CXR within 8 hours combined with P : F ratio of less than 288.8 mmHg. Of note, 14 patients were missing a P : F ratio. For these participants, CART analysis chose the following surrogate values: PaO2 of less than 117.5 mmHg for seven patients and SpO2 of less than 97.5% for the seven patients with no arterial blood gas (ABG) data. In patients who had both P : F ratio and PaO2 data available, a PaO2 of less than 117.5 mmHg was shown to reach the same final diagnosis as a P : F ratio of less than 300 mmHg 93.0% of the time; similarly an SpO2 of less than 97.5% agreed 88.4% of the time. Patients with a CXR and P : F ratio of more than 288.8 mmHg were considered “controls” with 85.7% specificity (two false negatives). The sensitivity, specificity, PLR, and NLR for these TRALI screening algorithms are shown in Table 4. The screening algorithm produced by the CART analysis appeared comparable to the initial algorithms with an equivalent overall misclassification rate of 13.5% (n = 23) but an improved specificity 89.7%. Subgroup analyses suggest that the CART-derived screening algorithms perform best when evaluating patients who were transfused in the operating room environment (Table 5). Of the 78 cases correctly identified by the CART-derived TRALI screening algorithm, only 11 (14.1%) of these were reported to the blood bank via passive reporting by the responsible clinical team.

Fig. 2.

(A) CART algorithm screening for TRALI. (B) CART algorithm screening for TACO.

TABLE 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of algorithms

| Algorithm | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PLR (95% CI) | NLR (95% CI) | Misclassification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRALI screening algorithm | |||||

| Manually derived | 0.86 (0.77–0.92) | 0.87 (0.77–0.93) | 6.71 (3.74–12.04) | 0.16 (0.10–0.27) | 0.13 (0.09–0.19) |

| CART derived | 0.84 (0.74–0.90) | 0.90 (0.80–0.95) | 8.18 (4.21–15.86) | 0.18 (0.11–0.29) | 0.13 (0.09–0.19) |

| TACO screening algorithm | |||||

| Manually derived | 0.96 (0.86–0.99) | 0.83 (0.73–0.90) | 5.77 (3.50–9.50) | 0.05 (0.01–0.18) | 0.11 (0.07–0.18) |

| CART derived | 0.87 (0.74–0.94) | 0.92 (0.83–0.97) | 11.25 (5.18–24.45) | 0.15 (0.07–0.29) | 0.10 (0.06–0.16) |

| Combined transfusion-related pulmonary complications screening algorithm | |||||

| Manually derived | 0.93 (0.87–0.96) | 0.83 (0.73–0.90) | 5.59 (3.39–9.19) | 0.08 (0.05–0.15) | 0.10 (0.07–0.15) |

| CART derived | 0.94 (0.89–0.97) | 0.83 (0.73–0.90) | 5.67 (3.45–9.33) | 0.07 (0.03–0.13) | 0.09 (0.06–0.14) |

TABLE 5.

Subgroup analyses evaluating CART algorithms effectiveness by transfusion location

| Transfusion environment | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PLR (95% CI) | NLR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRALI screening algorithm | ||||

| ICU (n = 58) | 0.81 (0.64–0.91) | 0.76 (0.52–0.91) | 3.41 (1.56–7.43) | 0.25 (0.12–0.50) |

| Operating room (n = 67) | 0.89 (0.74–0.97) | 0.97 (0.80–1.00) | 25.95 (3.77–178.58) | 0.11 (0.04–0.28) |

| Other hospital wards (n = 46) | 0.78 (0.52–0.93) | 0.93 (0.75–0.99) | 10.89 (2.80–42.35) | 0.24 (0.10–0.57) |

| TACO screening algorithm | ||||

| ICU (n = 34) | 0.77 (0.46–0.94) | 0.81 (0.57–0.94) | 4.04 (1.59–10.24) | 0.28 (0.10–0.79) |

| Operating room (n = 66) | 0.92 (0.76–0.98) | 0.97 (0.81–1.00) | 27.50 (3.99–189.37) | 0.09 (0.03–0.26) |

| Other hospital wards (n = 30) | 1.00 (0.20–1.00) | 0.96 (0.80–1.00) | 28.00 (4.09–191.88) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) |

| Combined transfusion-related pulmonary complications screening algorithm | ||||

| ICU (n = 71) | 0.94 (0.83–0.98) | 0.70 (0.46–0.87) | 3.14 (1.60–6.15) | 0.08 (0.03–0.26) |

| Operating room (n = 104) | 0.95 (0.86–0.98) | 0.86 (0.67–0.95) | 6.86 (2.76–17.07) | 0.06 (0.02–0.16) |

| Other hospital wards (n = 48) | 0.95 (0.73–1.00) | 0.93 (0.75–0.99) | 13.3 (3.48–50.76) | 0.05 (0.01–0.37) |

TACO screening algorithms

Of the 223 total study participants, 130 (n = 52 TACO, 78 controls) were included in the development and testing of the TACO screening algorithms. With the initial methods, utilizing existing definitions for determining algorithm cut points, 63 of the 130 patients were screen positive for TACO. A total of 50 TACO cases (96.2%) were correctly identified and 13 were false-positive results. The overall misclassification rate was 11.5%.

The subsequent CART analysis produced a modified TACO screening algorithm (Fig. 2B). In this analysis, the best predictor of TACO was a P : F ratio of less than 292.5 mmHg combined with the presence of any CXR within 8 hours. A total of 59 patients were missing a P : F ratio. For these study participants, CART used the following surrogates: PaO2 of less than 130 mmHg for 10 patients, SpO2 of less than 96.5% for 45 patients, and RR of more than 17.5/min for four patients. In patients who had both P : F ratio and surrogate data available, the above-defined thresholds were found to reach the same final diagnosis as a P : F ratio of less than 300 mmHg 80.3, 78.9, and 76.1% of the time, respectively. Patients with a P : F of more than 292.5 mmHg (or equivalent surrogate) were considered “controls” with 100% specificity (no false negatives). Patients with a P : F of less than 292.5 mmHg without a CXR within 8 hours were also considered controls with 85.1% specificity (seven false negatives). Using this algorithm, there was a total of six false-positive and seven false-negative results. The sensitivity, specificity, PLR, and NLR for these TACO screening algorithms can be seen in Table 4. Once again, when compared to the initial TACO screening algorithms, the overall misclassification rate was improved to 10.0%.

Subgroup analyses (Table 5) suggest that the TACO screening algorithm was most effective in a general hospital ward environment. In our population, this is most likely explained by indication bias. For example, at our institution it is not uncommon for intubated patients with existing arterial access in the ICU to have “routine” CXRs and blood gas evaluation. To the contrary, these investigations would typically only be ordered in the presence of a significant clinical deterioration for patients being transfused on the general hospital wards, as such improving the specificity of the algorithm in this environment. Of the 45 cases correctly identified by the CART-derived TACO screening algorithm, only five (11.1%) were reported to the blood bank by responsible clinical team.

Combined transfusion-related pulmonary complications screening algorithms

All 223 patients were included in the development and testing of the screening algorithms for the combined outcome of TRALI/transfused ALI and/or TACO versus no transfusion-related pulmonary complication. With the initial methods utilizing existing definitions for determining algorithm cut points, 148 patients were screen positive (135 of 145 cases, 13 of 78 controls). This produced a sensitivity of 93.1% (95% CI, 87.3%–96.5%), specificity of 83.3% (95% CI, 72.8%–90.5%), and overall misclassification rate of 10.3%. CART analysis for the combined outcome resulted in the algorithm displayed in Fig. 3. When compared to the initial screening method, the CART-derived algorithm again improved diagnostic accuracy with a sensitivity of 94.5% (95% CI, 89.0%–97.4%), while maintaining precision with a specificity of 83.3% (95% CI, 72.8%–90.5%). There were 13 false-positive and eight false-negative results producing an overall misclassification rate of 9.4%. The resulting PLR and NLR are presented in Table 4. In the subgroup analyses, the CART-derived algorithms appeared most effective when applied to patients admitted to the general hospital ward (Table 5).

Fig. 3.

CART algorithm screening for transfusion-related pulmonary complications.

Using this algorithm to screen for transfusion-related pulmonary complications, the best predictor was the presence of a CXR, irrespective of findings. For those patients with a CXR, if P : F ratio was also less than 292.5 mmHg then they were considered to represent “cases.” For the 16 patients missing a P : F ratio, the CART analysis used SpO2 of less than 97.5% as a surrogate marker of hypoxia. Patients with a CXR and P : F ratio of more than 292.5 mmHg were considered “controls” with 100% specificity (no false negatives). For patients without a CXR, RR of at least 27.5 was the best predictor of cases. Patients with a RR of less than 27.5 were considered controls. This data point was available for all patients and hence no surrogates were used. The results of the multiple variable logistic regression analyses evaluating the effect size of the variables included in the TRALI/transfused ALI, TACO, and combined CART analyses are shown in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Multivariate logistic regression

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRALI screening algorithm | |||

| Any CXR | 1.85 | 0.26–13.19 | 0.5370 |

| P : F ratio* | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | <0.001 |

| TACO screening algorithm | |||

| P : F ratio* | 0.97 | 0.96–0.99 | <0.001 |

| Any CXR | 4.65 | 0.40–54.15 | 0.2195 |

| Combined transfusion-related pulmonary complications screening algorithm | |||

| Any CXR | 2.31 | 0.34–15.70 | 0.39 |

| P : F ratio* | 0.97 | 0.96–0.98 | <0.001 |

| RR† | 1.03 | 0.96–1.09 | 0.4202 |

Based on unit increase of 100 mmHg.

Based on a unit increase of 10 breaths/min.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study, we developed electronic screening algorithms (Fig. 2) for the detection of TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO using readily available information contained within the EHR. The algorithms developed in this investigation were able to detect cases of TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO with good sensitivity and specificity (83.9%–94.6% and 83.3%–92.3%, respectively). These results support the notion that electronic screening algorithms can facilitate the detection of important clinical syndromes such as transfusion-related pulmonary complications. In addition, these findings are in keeping with previous efforts that have demonstrated the ability of automated electronic alerts to efficiently identify important clinical events and diagnoses in a timely manner and with superior sensitivity when compared with manual clinical detection alone.14,15,17

In comparing the logistic regression to the CART analysis, we see similar associations with the endpoints. The ORs in the logistic regression indicate that having a CXR, lower P : F ratio, or higher RR increases the risk of having TRALI or TACO. In this multivariate model, P : F ratio was the strongest predictor of disease. In the CART analysis, decision rules are presented for classifying a patient as a case or control. Considering statistical significance, the logistic regression finds that CXR and RR are not significant predictors of outcome when the P : F ratio is already in the model. However, all three are important independent predictors for classifying patients. Given the fact that logistic regression uses maximum likelihood for estimating variables and their standard errors, whereas the CART is nonparametric and uses node purity as criteria for determining risk factors for prediction, we should expect only broadly similar findings. Indeed, Kuhnert and coworkers18 describe similar disparities between CART and logistic regression.

TRALI and TACO remain the two most common causes of transfusion-related mortality reported to the FDA.2 Importantly, however, poor recognition and under-reporting of TRALI and TACO leave us with an incomplete understanding of the true epidemiology and attributable burden of these serious transfusion-related pulmonary complications. This fact is highlighted by the work of Kopko and colleagues6 who performed a lookback study after a fatal case of TRALI. The implicated donor in this fatality was found to have donated to 50 transfusion recipients. Of the 36 patients whose chart could be reviewed, eight had experienced severe respiratory decompensation after administration of the implicated blood product and only two of these were reported to the blood bank. Further evidence of our incomplete understanding of TRALI epidemiology can be seen in the marked discrepancies in reported incidence rates when comparing passive to active surveillance strategies. As an example, historic TRALI incidence rates have been reported to be approximately 1 case per 40,000 units distributed when evaluated with passive surveillance techniques.19 This incidence rate contrasts with the recent report of Toy and colleagues5 who noted an incidence rate of 1:4000 in the year 2006 (before the implementation of TRALI mitigation strategies) when evaluating transfusion recipients with active surveillance techniques.

Similar concerns exist regarding the recognition and reporting of TACO as well. Indeed, these concerns were recently highlighted by Narick and colleagues.7 In this investigation, the authors performed prospective active surveillance for TACO after plasma transfusion. In this 1-month prospective evaluation, the investigators identified four TACO episodes associated with 272 total plasma unit transfusions in 84 unique patients (incidence rate 4.8%). Notably, none of these reactions were reported to the blood bank by the responsible clinical service.

With the rapidly expanding adoption of EHRs, innovative data interrogation and extraction strategies have become possible. Such strategies may afford unique opportunities for improving our understanding of various conditions and outcomes of interest. To this end, we have previously shown the value of leveraging such technology for the identification of other acute care syndromes such as ALI,14,15,20 ventilator-induced lung injury,21 and sepsis.22 Similarly beneficial computer-based systems have been developed in other disciplines as well. As examples, Bates and coworkers23 have developed electronic solutions to remedy incomplete capture rates for adverse drug reactions and hospital-acquired infectious complications. In 1991, Classen and colleagues24 reported improved identification of adverse drug reactions with a case detection rate that was 80 times higher with computer screening than with passive reporting alone. Evans and others25,26 have reported similar benefits with computer surveillance for hospital-acquired infections and antibiotic use.

Notably, the present investigation is not the first to evaluate novel EHR-facilitated active surveillance strategies for TRALI. In 2005, Finlay and coworkers27 noted, in a retrospective pilot study, improved sensitivity for identifying TRALI cases with computer screening for a P : F ratio of 300 mmHg or less when compared to passive reporting. When this electronic screening algorithm was used prospectively to investigate the incidence and risk factors for TRALI,5 89 TRALI cases were identified during the 3-year study period. However, five cases were identified only after transfusion reactions were reported the institutional blood bank by the responsible clinical team. In all five cases, these patients were missed electronically either because an ABG was ordered outside of the 12-hour time frame after blood product issue, or a FiO2 was not recorded, precluding the calculation of a P : F ratio. In this instance, the requirement of an ABG to adjudicate a diagnosis of TRALI was a major limitation in the success of the algorithm to detect less severe cases of TRALI or cases in which an ABG could not be obtained for other clinical reasons. In the present investigation, we were able to overcome this major limitation through the additional inclusion of SpO2 and isolated PaO2 data in our algorithms to act as surrogate markers of hypoxemia.

A second limitation of the prospective electronic screening used in the initial study by Toy and coworkers5 is the need for manual review of the CXR reports to identify bilateral infiltrates. This manual step consumes personnel time and can be further complicated by the varied terminology used to describe pulmonary infiltrates by different radiologists. In contrast, the present investigation removes this manual review step and instead substitutes simply whether or not a CXR was obtained. Furthermore, this method expedites screening and diagnosis as data regarding CXR ordering will become available in the EHR much earlier, before radiologists have reported films.

In addition to improving our understanding of TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO epidemiology, active electronic screening may result in more timely identification of cases. As a result of establishing techniques for the time-efficient identification of TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO cases we can address two major barriers to progress in the prevention and treatment of TRALI and TACO episodes, namely: 1) early provision of relevant therapies and 2) early identification of potential study participants for prospective studies, including interventional clinical trials aiming to mitigate the impact of these syndromes on patient-important outcomes. In addition, the rapid recognition and reporting of these syndromes may prompt the identification of other in-date transfusables from the implicated donors. This may in turn facilitate the testing and removal of potentially harmful blood products from stock before being transfused to another patient, therefore potentially preventing further TRALI reactions.

In current practice, a major barrier to prospective active surveillance that requires manual clinical review relates to the issue of scalability. Indeed, the inability to manually monitor all transfusion recipients after receipt of the blood components is a major barrier to active TRALI and TACO surveillance. Although a significant barrier for active surveillance using manual data collection techniques, accurate computer-aided algorithms are mostly insensitive to the large volume of data generated by surveying an entire transfusion practice. As such we feel that these electronic screening algorithms offer the benefit of improved scalability when compared to manual screening alone.

Although the well-phenotyped study population and robust, well-validated electronic databases and data capture techniques are strengths of the current investigation, a number of limitations deserve note. The first limitation relates to the quality of the source data recorded in the EHR. If pertinent clinical data are missing or inaccurate in the EHR, a transfusion-related pulmonary complication may be either missed or incorrectly adjudicated as an outcome of interest by the electronic screening algorithm. However, the use of automated data extraction techniques have previously been shown to improve the accuracy of data capture when compared to manual data extraction.15 Therefore, the use of electronic data capture techniques is expected to outperform similar data capture using manual chart review techniques. In addition, the generalizability of these screening algorithms may be limited at some institutions due to the lack of such a robust EHR or health information technology infrastructure. While this may presently be a limiting factor, there is a movement toward the nationwide implementation of EHRs. As such we feel that in future, utilization of such a screening tool would in fact be possible.

A second limitation with this study is the single-center, tertiary care nature of the institution providing care to the study population. As a result of this limitation, we cannot comment on the external validity and generalizability of these screening algorithms in other populations. Rather, validation of the screening algorithms in an alternate study population is needed before recommending the broad utilization of these transfusion-related pulmonary complication screening techniques.

A third limitation relates to the selection of our derivation cohort. While this data set represents a very robust group of patients who were adjudicated a final diagnosis by expert reviewers, using the best available standard definitions, it is possible that the sensitivity of our algorithms has been inflated by the use of electronic alerts for their initial selection into the primary study. As described above, study personnel were alerted to review a patient’s medical record if their P : F ratio decreased to less than 300 mmHg or SpO2 less than 97% (Table 2). These alerts were generated electronically upon data entry into the EHR. Therefore, it is possible that patients in our study cohort had more electronic data available in their EHRs than other potential TRALI patients who may have been missed in the initial study.

Finally, although our findings support the use of electronic algorithms to screen for potential TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO episodes, we cannot draw any conclusions at this stage regarding how these screening algorithms may facilitate clinical management and patient outcome. Although we anticipate the screening algorithms may allow for a reduced time to diagnosis and treatment and hence improved patient outcomes, this will need to be investigated in a separate study designed to detect such outcomes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that electronic screening algorithms for TRALI/transfused ALI and TACO can detect cases with sufficient sensitivity and specificity. As a result, these algorithms may be used to better define the epidemiology and attributable burden of these important transfusion-related pulmonary complications. In light of their highly efficient nature, these innovative screening techniques may also facilitate the enrollment of patients into future prospective trials evaluating potential targeted therapies. From a clinical perspective, this may also allow for earlier diagnosis and intervention, potentially improving patient-important outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Department of Anesthesia, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

The authors thank Tami Krpata for her time and efforts with data collection for the initial patient cohort.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ABG

arterial blood gas

- ALI

acute lung injury

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

- CART

classification and regression tree

- CVP

central venous pressure

- CXR

chest radiograph

- EHR(s)

electronic health record(s)

- HR

heart rate

- ICU

intensive care unit

- NLR

negative likelihood ratio

- PCWP

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

- P:F ratio

partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio

- PLR

positive likelihood ratio

- RR

respiratory rate

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- TACO

transfusion-associated circulatory overload

- TRALI

transfusion-related acute lung injury

Footnotes

Attribution for work: LC—study design, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation; AS—data acquisition and manuscript revision; GAW—data acquisition and manuscript revision; PT—data acquisition, interpretation, and manuscript revision; OG—data acquisition, data interpretation, and manuscript revision; MM—data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript revision; VH—data acquisition and manuscript revision; JP—data acquisition and manuscript revision; DJL—study conception, study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript revision.

There are no disclaimers.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the manuscript submitted to TRANSFUSION.

References

- 1.SHOT UK. Serious Hazards of Transfusion Annual Report 2010 Summary (monograph on the internet) 2010 [cited 2012 May 23]. Available from: http://www.shotuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/SHOT-2010-Summary1.pdf.

- 2.FDA. Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion (monograph on the internet) 2010 [cited 2012 May 23]. Available from: URL: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/ReportaProblem/TransfusionDonationFatalities/UCM254860.pdf.

- 3.Kleinman S, Caulfield T, Chan P, Davenport R, McFarland J, McPhedran S, Meade M, Morrison D, Pinsent T, Robillard P, Slinger P. Toward an understanding of transfusion-related acute lung injury: statement of a consensus panel. Transfusion. 2004;44:1774–89. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.04347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National healthcare safety network manual—biovigilance component protocol. Altanta, GA: Center for Disease Control; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toy P, Gajic O, Bacchetti P, Looney MR, Gropper MA, Hubmayr R, Lowell CA, Norris PJ, Murphy EL, Weiskopf RB, Wilson G, Koenigsberg M, Lee D, Schuller R, Wu P, Grimes B, Gandhi MJ, Winters JL, Mair D, Hirschler N, Sanchez Rosen R, Matthay MA. Transfusion related acute lung injury: incidence and risk factors. Blood. 2012;119:1757–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-370932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopko PM, Marshall CS, MacKenzie MR, Holland PV, Popovsky MA. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: report of a clinical look-back investigation. JAMA. 2002;287:1968–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.15.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narick C, Triulzi DJ, Yazer MH. Transfusion-associated circulatory overload after plasma transfusion. Transfusion. 2012;52:160–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson ND, Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A, Fernandez-Segoviano P, Aramburu JA, Najera L, Stewart TE. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: underrecognition by clinicians and diagnostic accuracy of three clinical definitions. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2228–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181529.08630.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toy P, Popovsky MA, Abraham E, Ambruso DR, Holness LG, Kopko PM, McFarland JG, Nathens AB, Silliman CC, Stroncek D. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: definition and review. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:721–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000159849.94750.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. 1992. Chest. 2009;136:e28. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herasevich V, Pickering BW, Dong Y, Peters SG, Gajic O. Informatics infrastructure for syndrome surveillance, decision support, reporting, and modeling of critical illness. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:247–54. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chute CG, Beck SA, Fisk TB, Mohr DN. The Enterprise Data Trust at Mayo Clinic: a semantically integrated warehouse of biomedical data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:131–5. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2009.002691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herasevich V, Yilmaz M, Khan H, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O. Validation of an electronic surveillance system for acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1018–23. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1460-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alsara A, Warner DO, Li G, Herasevich V, Gajic O, Kor DJ. Derivation and validation of automated electronic search strategies to identify pertinent risk factors for postoperative acute lung injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:382–8. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gajic O, Rana R, Winters JL, Yilmaz M, Mendez JL, Rickman OB, O’Byrne MM, Evenson LK, Malinchoc M, DeGoey SR, Afessa B, Hubmayr RD, Moore SB. Transfusion-related acute lung injury in the Critically Ill, Prospective Nested Case-Control Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:886–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-271OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finlay-Morreale HE, Louie C, Toy P. Computer-generated automatic alerts of respiratory distress after blood transfusion. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:383–5. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhnert PM, Do K, McClure R. Combining non-parametric models with logistic regression: an application to motor vehice injury data. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2000;34:371–86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eder AF, Herron R, Strupp A, Dy B, Notari EP, Chambers LA, Dodd RY, Benjamin RJ. Transfusion-related acute lung injury surveillance (2003–2005) and the potential impact of the selective use of plasma from male donors in the American Red Cross. Transfusion. 2007;47:599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kor DJ, Warner DO, Alsara A, Fernandez-Perez ER, Malinchoc M, Kashyap R, Li G, Gajic O. Derivation and diagnostic accuracy of the surgical lung injury prediction model. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:117–28. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31821b5839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herasevich V, Tsapenko M, Kojicic M, Ahmed A, Kashyap R, Venkata C, Shahjehan K, Thakur SJ, Pickering BW, Zhang J, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O. Limiting ventilator-induced lung injury through individual electronic medical record surveillance. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:34–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fa4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herasevich V, Pieper MS, Pulido J, Gajic O. Enrollment into a time sensitive clinical study in the critical care setting: results from computerized septic shock sniffer implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:639–44. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bates DW, Evans RS, Murff H, Stetson PD, Pizziferri L, Hripcsak G. Detecting adverse events using information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:115–28. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Burke JP. Computerized surveillance of adverse drug events in hospital patients. JAMA. 1991;266:2847–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans RS, Larsen RA, Burke JP, Gardner RM, Meier FA, Jacobson JA, Conti MT, Jacobson JT, Hulse RK. Computer surveillance of hospital-acquired infections and antibiotic use. JAMA. 1986;256:1007–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirschhorn LR, Currier JS, Platt R. Electronic surveillance of antibiotic exposure and coded discharge diagnoses as indicators of postoperative infection and other quality assurance measures. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993;14:21–8. doi: 10.1086/646626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finlay HE, Cassorla L, Feiner J, Toy P. Designing and testing a computer-based screening system for transfusion-related acute lung injury. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:601–9. doi: 10.1309/1XKQKFF83CBU4D6H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]