Abstract

Background

Social protection (i.e. cash transfers, free schools, parental support) has potential for adolescent HIV-prevention. We aimed to identify which social protection interventions are most effective and whether combined social protection has greater effects in South Africa.

Methods

In this prospective longitudinal study, we interviewed 3516 adolescents aged 10-18 between 2009 and 2012. We sampled all homes with a resident adolescent in randomly-selected census areas in four urban and rural sites in two South African provinces. We measured household receipt of fourteen social protection interventions and incidence of HIV-risk behaviors. Using gender-disaggregated multivariate logistic regression and marginal-effects analyses, we assessed respective contributions of interventions and potential combination effects.

Results

Child-focused grants, free schooling, school feeding, teacher support, and parental monitoring were independently associated with reduced HIV-risk behavior incidence (OR 0.10-0.69). Strong effects of combination social protection were shown, with cumulative reductions in HIV-risk behaviors. For example, girls’ predicted past-year incidence of economically-driven sex dropped from 11% with no interventions, to 2% amongst those with a child grant, free school and good parental monitoring. Similarly, girls’ incidence of unprotected/casual sex or multiple-partners dropped from 15% with no interventions to 10% with either parental monitoring or school feeding, and to 7% with both interventions.

Conclusion

In real-world, high-epidemic conditions, ‘combination social protection’ shows strong HIV-prevention effects for adolescents and may maximize prevention efforts.

Keywords: Prevention, Social protection, Adolescents, South Africa

Introduction

Although the rate of new HIV infections is falling in Sub-Saharan Africa, 575 adolescents are still infected with HIV everyday.1 With strong evidence of socio-economic drivers of this epidemic,2 there is increasing interest in the HIV-prevention impacts of social protection.3 Early research showed that provision of pensions to grandparents had positive impacts of outcomes such as education and nutrition of adolescent girls in their households.4 Subsequently, the evidence on adolescent HIV-prevention has focused on unconditional national cash transfer programs.5 In Kenya, South Africa, and Malawi, these have been shown to reduce HIV-infection risks amongst adolescents, particularly girls.6–9 However, a new study has suggested that ‘combination social protection’ – providing both ‘cash’ and psychosocial ‘care’ – may be potentially more effective than single interventions.10

Combination Social Protection: the theory

The theory of combination social protection is based on three premises. First, HIV-risk behaviors are influenced by adversities in different domains of an adolescent’s life. For example, poverty can be a driver of transactional sex, but so also can familial illness and child physical abuse.11 Second, different sexual behaviors increase HIV-infection risks, but may have quite different causal mechanisms. For example, age-disparate sex is increased by poverty, exclusion,12–14 and household income shocks,15,16 whereas unprotected sex is increased by intimate partner violence17,18 and child abuse.10 Third, childhood adversities can cumulate to increase HIV-risk behaviors more than single adversities.19 Thus, combination social protection has the potential to maximize HIV-prevention impacts by ameliorating simultaneous risks in different life domains.20

Policy-identified need for evidence

Research in high-income countries on interventions that look similar to combinations of social protection have shown impacts on other adolescent risk behaviour outcomes such as youth offending.21 In Latin America, research on combination social protection such as the Progresa/Opportunidades/Prospera initiatives showed improvements in child nutrition and education. 22 However, to our knowledge, no studies to date in high or low income countries have examined impacts of different combinations of social protection on adolescent HIV risks. In 2014, UNICEF, UNAIDS, UNDP, PEPFAR-USAID, and the World Bank conducted a series of high-level meetings. These aimed to ascertain the evidence needs of Southern and Eastern African governments regarding social protection and HIV-prevention.a Policy-makers identified two key and unanswered requirements: first, to distinguish which specific types of social protection interventions are effective in adolescent HIV-risk reduction; and second, to test whether there are cumulative prevention benefits of combination social protection. This study aims to address these questions in a multi-site longitudinal sample from South Africa.

Methods

Participants and procedures

3516 adolescents aged 10-18 (56.7% female) were interviewed at baseline (2009-10), and followed up at one year (2011-12). Refusal rate at baseline was <2.5% and one-year retention rate was 96.8%. Two South African provinces were selected in consultation with the South African National Departments of Social Development, Health and Education: Mpumalanga and the Western Cape. Within these provinces, two urban and two rural health districts with >30% antenatal HIV-prevalence were randomly selected. Within each health district, sequentially-numbered census enumeration areas were randomly sampled until sample size was reached. In each area, every household was visited and was included in the study if they had a resident adolescent. One adolescent per household was interviewed face-to-face for 60-70 minutes. Questionnaires and consent forms were translated into Xhosa, Zulu, Sotho, and Tsonga and checked with back-translation. Adolescents participated in the language of their choice.

Ethical protocols were approved by the Universities of Oxford, Cape Town, and KwaZulu-Natal and by provincial Health and Education Departments. Adolescents and primary caregivers provided voluntary informed consent. No incentives were given apart from refreshments and certificates of participation. All interviewers were trained in working with vulnerable youth and confidentiality was maintained except where participants were at risk of significant harm or requested assistance. Where participants reported abuse, rape, or risk of significant harm, referrals were made to child protection, health and HIV/AIDS services with follow-up support.

Measures

Adolescent HIV-risk behaviors were measured at baseline, and new incidence of HIV-risk behaviors measured at follow-up, using scales from the National Survey of HIV and Sexual Behavior amongst Young South Africans and the SA Demographic and Health Survey.23 Prior evidence suggests that HIV-risk behaviors may cluster, and thus risks were grouped into risks with evidence of poverty, deprivation and exploitation drivers: ‘economic sex’ (transactional and age-disparate sex), risks with evidence of adolescent developmental-level and social drivers: ‘incautious sex’ (unprotected sex, multiple partners, casual partners, and sex using substances), and ‘pregnancy’ (females only, current and past pregnancy). Transactional sex was past-year incidence of sex in exchange for food, shelter, school fees, transport, or money; age-disparate sex was past-year incidence of having a sexual partner >5 years older than the adolescent.22 Unprotected sex was ‘sometimes’ ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ using condoms when having sex in the past year (versus ‘always’ using condoms or no sexual activity). Multiple sexual partners was having ≥2 partners in the past year.24 Casual partners was having sexual partners who were not regular boyfriends/girlfriends in the past year. Sex whilst using substances was past-year sex whilst drunk or using any drug. Pregnancy history and current pregnancy – both a marker of unprotected sex and also a risk factor for increased unprotected sex and sero-conversion for adolescents25 – were measured at baseline and follow-up.

Social Protection and social care provisions were measured at baseline for 14 components.b Child-focused cash transfer receipt was measured as household access to either a child support grant or foster child grant.7 Pension was within-household access to an old-age grant. School feeding was daily, free lunches provided at school, and provision of free school transport and free school uniform were also measured. Access to food gardens was receiving food from a school or community garden; food parcels or soup kitchen feeding were regular, reliable provision of food parcels to the household or free meals from any organization. Home and community-based carer support was at-least monthly household visits from a home-based caregiver, nurse, or volunteer providing medical and social support. Teacher social support was social, practical, or emotional support from a teacher, using a standardized scale used previously in South Africa.26 School counselor was past-year school-based counseling. Positive parenting (e.g., primary caregiver praise and warmth) and parental monitoring (e.g., having set times to be home, parental knowledge of whereabouts) were measured using validated Alabama Parenting Questionnaire subscales.27 Free schooling required both no-fees school and free schoolbooks (many ‘free’ schools required financial contributions for schoolbooks in order to allow children to take exams). Evidence suggests that in order to show effects, social protection requires sustained and predictable duration as well as current receipt.28 Consequently, each intervention and care provision was dichotomized into receipt/no receipt, with positive coding requiring exposure at both baseline and one-year follow-up.

Pre-selected covariates included factors potentially affecting HIV-risk or social protection access. Adolescent age, urban/rural location, school enrollment, informal/formal housing, migration, number of children in the home, female primary caregiver, and maternal and paternal death were measured using items adapted from the South African Census. Food insecurity was measured using items from the National Food Consumption Survey7 and determined as days in the past week with insufficient food in the home. HIV-prevention knowledge at baseline and follow-up was measured using a ‘free-listing’ approach, asking ‘can you write any things you think a person can do to avoid getting HIV or AIDS?’, as pre-existing lists of true and false prevention methods can over-estimate knowledge levels. Scores were calculated by summed number of accurate methods (e.g. ‘use a condom’), minus summed inaccurate methods (e.g. ‘do not share food with an HIV-positive person’). Participants also indicated whether they had a birth certificate, a frequent requirement for accessing social protection programs.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted in three stages in SPSS 21.0 and STATA 13.1, using the longitudinal sample (n=3401). Since few adolescents younger than 12 years reported ever having sex (n=9), analyses were limited to the 2668 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years (male 1170, female 1498). Analyses were gender-disaggregated, as previous studies have suggested gender differences in HIV risk and protective factors.10

First, descriptive statistics for all outcomes, social protection variables, and covariates were calculated (Table 1). Social protection types were excluded where numbers reached were too small for reliable analysis. To check for multicolinearity, social protections and covariates were entered into a linear regression for each of incautious sex, economic sex, and pregnancy. Both tolerance values and the spread of variance proportions on small eigenvalues suggested no multicolinearity.

Table 1. Characteristics of 2668 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years included in analyses.

| All | Girls | Boys | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 2668 | 1498 | 1170 |

| Social Protection Interventions (Received at Times 1 and 2) | |||

| Child support or foster child grant | 1486 (55.7%) | 852 (56.9%) | 634 (54.2%) |

| Pension | 136 (5.1%) | 81 (5.4%) | 55 (4.7%) |

| Free school and books | 1398 (52.4%) | 798 (53.3%) | 600 (51.3%) |

| Teaching support | 211 (7.9%) | 121 (8.1%) | 90 (7.7%) |

| School counselor | 98 (3.7%) | 55 (3.7%) | 43 (3.7%) |

| Free school meals | 1930 (72.3%) | 1064 (71.0%) | 866 (74.0%) |

| Food gardens | 132 (4.9%) | 67 (4.5%) | 65 (5.6%) |

| Food parcels or soup kitchens | 13 (0.5%) | 10 (0.7%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| Positive parenting | 664 (24.9%) | 376 (25.1%) | 288 (24.6%) |

| Good parental monitoring | 572 (21.4%) | 358 (23.9%) | 214 (18.3%) |

| Outcomes (Time 2) a | |||

| Economically-driven sex | 156 (5.8%) | 99 (6.6%) | 57 (4.9%) |

| Incautious sex | 490 (18.4%) | 240 (16.0%) | 250 (21.4%) |

| Ever pregnant | - | 71 (4.7%) | - |

| Covariates b | |||

| Age | 14.2 (1.6) | 14.3 (1.7) | 14.2 (1.6) |

| Number of days without enough food in the household | 0.9 (1.6) | 0.9 (1.6) | 0.8 (1.6) |

| Informal housing | 820 (30.7%) | 471 (31.4%) | 349 (29.8%) |

| Urban location | 1309 (49.1%) | 717 (47.9%) | 592 (50.6%) |

| School non-enrolment | 66 (2.5%) | 40 (2.7%) | 26 (2.2%) |

| Moved more than twice | 935 (35.0%) | 558 (37.2%) | 377 (32.2%) |

| Number of children in the home | 2.6 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.3) |

| Female primary caregiver | 2366 (88.7%) | 1354 (90.4%) | 1012 (86.5%) |

| Mother dead | 326 (12.2%) | 170 (11.3%) | 156 (13.3%) |

| Father dead | 588 (22.0%) | 350 (23.4%) | 238 (20.3%) |

| Child has birth certificate | 2544 (95.4%) | 1416 (94.7%) | 1128 (96.4%) |

| HIV knowledge | 1.8 (1.4) | 1.8 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.3) |

| Economically-driven sex | 113 (4.2%) | 85 (5.7%) | 28 (2.4%) |

| Incautious sex | 339 (12.7%) | 171 (11.4%) | 168 (14.4%) |

| Ever pregnant | - | 46 (3.1%) | - |

Data are number of participants, number of participants (%), or mean (standard deviation).

Reporting both incautious and economic sex: 4% boys, 5% girls.

All covariates were measured at Time 1, except HIV knowledge, which is included from Time 2.

Second, associations between specific social protections and HIV risk behaviors were assessed in multivariable logistic regressions. To identify social protections with independent effects, two models were run.29 In Model 1, all interventions and covariates were included with each of the following HIV risk behaviors at Time 2 as outcomes: incautious sex (males and females), economic sex (males and females), and pregnancy (females only). Each analysis at this stage controlled for covariates HIV-risk or social protection access: baseline HIV-risk behavior, age, poverty, urban-rural location, school nonenrolment, informal/formal housing, migration, number of children in the home, female primary caregiver, maternal and paternal death, possession of a birth certificate, and HIV knowledge. For Model 2, all pre-selected covariates were included while interventions were selected for inclusion on the basis of p<0.10, to prevent potentially important variables from being omitted.28 Covariates were included in both models to control for potential confounding due to the non-randomised allocation of interventions.

Third, we tested whether there are greater HIV-prevention effects from combining social protections. All social protection variables and covariates that were included in Model 2 were entered into a marginal effects analysis in STATA using binary logistic regression for each outcome. Each possible combination of included social protection variables on HIV-risk behaviors was tested in each analysis, with all covariates held at their mean values, to determine how the predicted probability of the outcome alters when different interventions (and combinations of interventions) are present.

Role of the funding source

The study’s sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Sample characteristics and social protection access (Table 1)

Respondents had a mean age of 14.2 years at follow-up (14.2 males, 14.3 females, both ranged 10-19). They reported a mean of 2.3 days without enough food in the past week. 31% lived in informal (shack) housing, 2.5% had left school before completion. 5% of boys and 7% of girls reported economically-driven sex at follow-up. 21% of boys and 16% of girls reported incautious sex at follow-up. Female pregnancy at follow-up was 5%. Social protection interventions that reached less than 100 adolescents (<0.3% of the sample) were excluded (school counsellors, food parcels, and soup kitchens). Remaining social protections were: the child support/foster child grant (received by 56% of adolescents), pension in the household (5%), free schooling and books (52%), teacher support (8%), school counselling (4%), access to food gardens (5%), positive parenting (25%), and good parental monitoring (21%).

Independent associations of social protection interventions with HIV-risk incidence (Table 2)

Table 2. Interventions and Covariates Associated with Incident HIV-Risk Behaviors in Multivariable Binary Logistic Regression Analyses for Girls and Boys.

| Girls (n=1498) |

Boys (n=1170) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incautious Sexa | Economic Sexb | Pregnancyc | Incautious Sexd | Economic Sexe | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| AOR (95% CI) | p value | AOR (95% CI) | p value | AOR (95% CI) | p value | AOR (95% CI) | p value | AOR (95% CI) | p value | |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Child grants | - | - | 0.51 (0.32-0.83) | 0.007 | 1.64 (0.89-3.00) | 0.110 | - | - | - | - |

| Free school and books | - | - | 0.36 (0.22-0.60) | <0.0001 | 0.47 (0.21-1.03) | 0.59 | 0.69 (0.48-0.99) | 0.046 | - | - |

| School feeding | 0.64 (0.44-0.93) | 0.020 | - | - | 0.32 (0.15-0.67) | 0.003 | - | - | - | - |

| Parental monitoring | 0.66 (0.43-1.01) | 0.056 | 0.62 (0.34-1.15) | 0.130 | 0.55 (0.25-1.20) | 0.134 | 0.51 (0.30-0.87) | 0.013 | 0.10 (0.01-0.70) | 0.021 |

| Teacher support | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.46 (0.21-0.99) | 0.046 | - | - |

| Incautious sex, Time 1 | 6.36 (4.24-9.54) | <0.0001 | - | - | - | - | 3.82 (2.57-5.68) | <0.0001 | - | - |

| Economic sex, Time 1 | - | - | 3.78 (2.05-6.98) | <0.0001 | - | - | - | - | 3.32 (1.21-9.09) | 0.019 |

| Pregnancy, Time 1 | - | - | - | - | 14.95 (6.77-33.03) | <0.0001 | - | - | - | - |

| Age | 1.61 (1.44-1.81) | <0.0001 | 1.32 (1.14-1.53) | 0.0002 | 1.73 (1.38-2.16) | <0.0001 | 1.67 (1.50-1.86) | <0.0001 | 1.46 (1.22-1.75) | <0.0001 |

| Food insecurity | 1.10 (1.00-1.21) | 0.041 | 0.93 (0.81-1.06) | 0.280 | 1.02 (0.87-1.20) | 0.827 | 1.04 (0.94-1.16) | 0.414 | 1.04 (0.87-1.24) | 0.662 |

| Informal housing | 0.61 (0.41-0.91) | 0.016 | 1.33 (0.80-2.20) | 0.271 | 0.36 (0.17-0.77) | 0.008 | 1.17 (0.80-1.70) | 0.428 | 0.72 (0.38-1.37) | 0.315 |

| Urban location | 1.01 (0.72-1.44) | 0.942 | 1.02 (0.64-1.63) | 0.922 | 1.40 (0.76-2.59) | 0.287 | 1.11 (0.77-1.58) | 0.577 | 1.02 (0.58-1.80) | 0.936 |

| School non-enrolment | 0.99 (0.41-2.29) | 0.981 | 0.63 (0.22-1.78) | 0.380 | 0.84 (0.25-2.78) | 0.772 | 2.39 (0.60-9.55) | 0.216 | 3.27 (0.62-17.27) | 0.163 |

| Migration | 1.60 (1.11-2.29) | 0.011 | 1.12 (0.69-1.82) | 0.638 | 2.13 (1.15-3.93) | 0.016 | 1.60 (1.11-2.30) | 0.012 | 1.12 (0.60-2.09) | 0.715 |

| Number of children in the home | 0.99 (0.89-1.09) | 0.786 | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | 0.400 | 0.86 (0.71-1.03) | 0.099 | 0.90 (0.79-1.03) | 0.113 | 0.86 (0.68-1.08) | 0.195 |

| Female primary caregiver | 1.11 (0.65-1.92) | 0.697 | 1.66 (0.75-3.65) | 0.211 | 2.73 (0.68-11.00) | 0.157 | 1.29 (0.79-2.08) | 0.310 | 0.82 (0.38-1.74) | 0.602 |

| Mother dead | 1.05 (0.65-1.69) | 0.851 | 1.86 (1.04-3.34) | 0.038 | 0.88 (0.38-2.02) | 0.760 | 0.69 (0.40-1.16) | 0.161 | 0.49 (0.17-1.45) | 0.196 |

| Father dead | 1.05 (0.73-1.53) | 0.778 | 1.15 (0.71-1.87) | 0.560 | 1.77 (1.00-3.15) | 0.051 | 0.88 (0.58-1.33) | 0.546 | 0.60 (0.27-1.33) | 0.206 |

| Child has birth certificate | 1.01 (0.53-1.92) | 0.987 | 0.76 (0.36-1.62) | 0.479 | 0.98 (0.37-2.60) | 0.961 | 1.08 (0.46-2.57) | 0.856 | 3.07 (0.38-24.97) | 0.294 |

| HIV Knowledge | 0.87 (0.70-1.09) | 0.216 | 0.91 (0.69-1.22) | 0.538 | 1.28 (0.89-1.86) | 0.187 | 1.15 (0.91-1.45) | 0.258 | 0.98 (0.65-1.46) | 0.901 |

AOR=adjusted odds ratio. Odds ratios are adjusted for all other variables displayed in the same table column. Statistically significant odds ratios (p<0.05) are bolded.

Constant B=−8.80.

Constant B=−6.27.

Constant B=−12.41.

Constant B=−9.27.

Constant B=−8.81.

Table 2 shows all factors that remained associated at p<0.10 with reduced HIV-risk behaviors in multivariable regressions, independent of all other social protection factors and covariates. For males, reduced incidence of incautious sex was significantly associated (p<0.05) with free schooling (OR 0.69, CI:0.48-0.99), parental monitoring (OR 0.51, CI:0.30-0.87), and teacher support (OR 0.46, CI:0.21-0.99), whilst reduced incidence of economic sex was associated with parental monitoring (OR 0.10, CI:0.01-0.70). For females, reduced incidence of incautious sex was associated with school feeding (OR 0.64, CI:0.44-0.93) and reduced incidence of economic sex was associated with child grants (OR 0.51, CI:0.32-0.83) and free schooling (OR 0.36 CI:0.22-0.60). Reduced incidence of pregnancy was associated with school feeding (OR 0.32, CI:0.15-0.67). Although receipt of child grants met the p<0.10 threshold to be included in Model 2 regressions for pregnancy, having children as an adolescent increases the probability of receiving child grants (i.e., a reverse causality). Consequently, receipt of child grants was treated as a covariate rather than a predictor of pregnancy in these models.

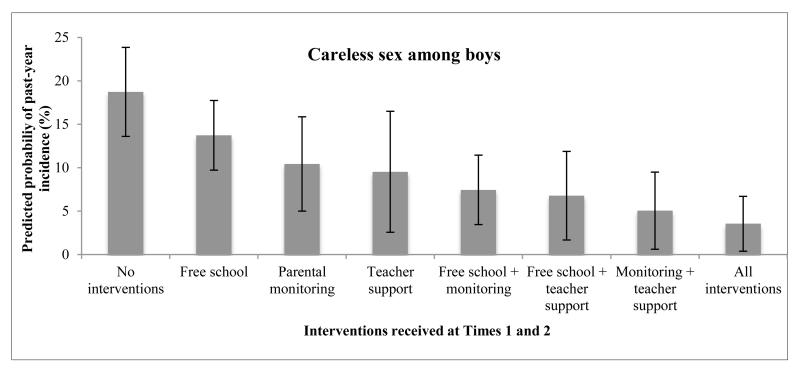

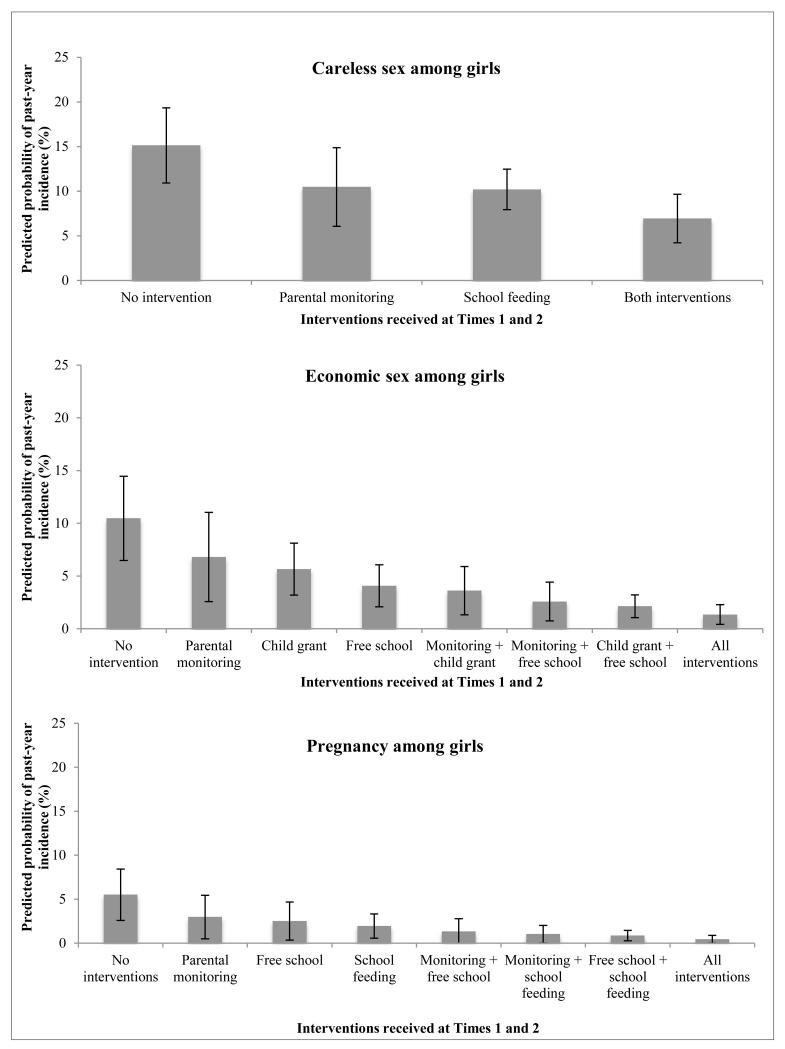

Associations of combination social protection interventions with HIV-risk behavior incidence (Figures 1–2)

Figure 1. Predicted incidence of incautious sex among adolescent boys (n=1170).

All analyses controlled for the following variables at Time 1: incautious sex, age, food insecurity, informal housing, urban location, school non-enrolment, migration, number of children in the home, female primary caregiver, maternal and paternal orphanhood, and having a birth certificate. We also controlled for HIV knowledge, measured at Time 2. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Predicted incidence of HIV-risk behaviors among adolescent girls (n=1498).

For incautious sex (A), economically-driven sex (B), and pregnancy (C). All analyses controlled for the following variables at Time 1: sexual risk behavior, age, food insecurity, informal housing, urban location, school non-enrolment, migration, number of children in the home, female primary caregiver, maternal and paternal orphanhood, and having a birth certificate. We also controlled for HIV knowledge, measured at Time 2. Analysis of pregnancy as an outcome controlled for receipt of a child support or foster child grant at Times 1 and 2. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Where two or more social protections were at p<0.10, interval estimates of the probability of the outcome showed which combinations of social protection interventions were significant, whilst controlling for covariates and baseline HIV-risk behavior. Analyses identified social protections that separately were not significantly associated with reduced HIV-risk behavior incidence, but showed significant reductions in outcome probability when combined with other social protections.

For boys, predicted probability of past-year incidence of incautious sex was 18.7% when receiving none of the included social protection interventions of free schooling, teacher support, or parental monitoring. With free school alone, it was 13.7%, with good parental monitoring alone, 10·4% and with teacher support alone, 9.5%. But with both free school and parental monitoring, boys’ incidence of incautious sex was 7.5%, with free school and teacher support, 6.8% and with parental monitoring and teacher support, 5.1%. Among boys who received all three interventions, past-year incidence of incautious sex was 3.5%.

For girls, parental monitoring was not independently associated with incautious sex, but when combined with school feeding, showed stronger associations than school feeding alone. Thus, girls’ past-year incidence of incautious sex when receiving none of the included social protection interventions was 15.1%. With good parental monitoring alone, it was 10.5%, and with school feeding alone, 10.2%. When both of these interventions were received, girls’ past-year incidence of incautious sex dropped to 6.9%.

Amongst girls, economically-driven sex also showed combination effects of social protection. Girls’ past-year incidence of economic sex when receiving none of the included social protection interventions was 10.5%. With parental monitoring alone, incidence was 6.8%, with a child-focused grant alone, 5.7%, and with free schooling alone, 4.1%. But with both parental monitoring and a child grant, girls’ incidence of economically-driven sex was 3.6%, with parental monitoring and free school, 2.6% and with a child grant and free school, 2.1%. Among girls who received all three interventions, past-year incidence of economically-driven sex was 2.1%.

Finally, combination social protection effects were shown on adolescent female pregnancy. Past-year incidence of pregnancy when receiving none of the included social protection interventions was 5.5%. With good parental monitoring alone, it was 3.0%, with free schooling, 2.5%, and with school feeding, 1.9%. But with both parental monitoring and free school, incidence of pregnancy was 1.3%; with parental monitoring and school feeding, 1.0%; and with free school and school feeding, 0.9%. Among girls who received all three interventions, pregnancy incidence was less than 0.5%.

Discussion

These findings have two key messages for adolescent HIV-prevention in South Africa, regarding the impacts of domains of social protection, and combinations of types of social protection.

First, they show that specific social protection interventions in three domains, cash, psychosocial support and education (or ‘cash, care and classroom’) independently reduce specific HIV-risk behaviors amongst adolescent boys and girls. In particular, child-focused grants, parental monitoring, free schooling, school feeding, and teacher support each show significant prevention effects, independently of other social interventions, and after controlling for covariates and baseline HIV-risk behaviour.

Secondly, findings demonstrate that combination social protection interventions can have strong effects on HIV-risk behavior reduction, independently of socio-demographic co-factors and baseline HIV-risk. For example, past-year incidence rates of incautious sex amongst males reduced more than three-fold, from 22% with no identified social protection interventions to 6% with a combination of free school, parental monitoring, and teacher support. The predicted probability of incautious sex amongst females halved from 15% to 7% with combined social protections of parental monitoring and school feeding, and economic sex amongst females reduced five-fold from 10% to 2% with combined child grants and free schooling.

These findings demonstrate that combination social protection is likely to be more effective than stand-alone programs, but also show that specific combinations should be selected for effects on particular HIV-risks and genders. By getting the right combinations of child-focused cash transfers, free schooling, school feeding, parental monitoring, and teacher support, we have potential to reduce adolescent HIV-risks.

The study raises further research questions regarding why and how combination social protections reduce HIV-risks. We know that sexual decisions have complex behavioural risk factors: It may be that different types of social protection are addressing simultaneous but different sources of risk – for example a household cash transfer may reduce the financial need for an adolescent girl to have a ‘sugar daddy’, whilst access to education through free school may reduce her exposure to older men in the community, and good parenting may provide guidance and reduce emotional needs for affection from a high-risk sexual partner. It may also be that some adolescents are particularly vulnerable to one type of risk but that not all adolescents are vulnerable to the same type of risk, and that combination social protection is necessary in order to have an impact at a population level in endemic countries. Theoretical models of child and adolescent development and research on risks such as youth offending30 suggest that single interventions may not be powerful enough alone to impact adolescent risk-taking behaviour. Thus it is also possible that multi-component approaches, providing a compound effect, are required in order to counter the high-risk environments that characterise these adolescents’ lives. Future research – both qualitative and quantitative – will be of great value in identifying these pathways.

This study has a number of limitations and strengths that should be considered. Firstly, randomised controlled trial designs are more reliable in determining causality. However, quasi-experimental panel studies allow simultaneous testing of multiple possible combinations of interventions, and can refine these into a smaller number of combinations for future testing in randomized trials. Secondly, the study only has two time-points, a year apart. It will be important to examine longer-term associations of social protection and how they may influence HIV-risk behavior as adolescents progress into young adulthood.31 However, longitudinal studies have the important advantage of allowing analyses to control for baseline HIV-risk behaviours. This makes it possible to analyse incident HIV-risk behaviors, which allows for stronger casual assumptions. Thirdly, it would also be valuable to examine combination social protection in other countries and in population sub-groups not sampled in this study, particularly street-youth, adolescents in prisons and in residential institutions.3 However, this study used a systematic random sampling method, and by follow-up reached the original adolescents across seven provinces within South Africa. Fourthly, although all the behavioral outcomes in this study have strong associations with HIV-infection amongst Southern African adolescents, it would be valuable for future studies to use HIV-biomarker endpoints, which is becoming more feasible with accessibility of new assays that can detect time of infection. Finally, this study was restricted to social protection interventions. Future research should examine social protection in combination with biomedical and behavioral interventions, to determine whether cross-sectoral combinations can provide even greater HIV-prevention impacts.

This study therefore suggests clear needs for future research. Randomised controlled trials with biomarker HIV-incidence outcomes and long-term follow-up would be of great value. Testing of moderator and mediator effects in quasi-experimental and experimental data, combined with qualitative research, could help identify causal pathways by which combination social protection may be impacting HIV risks. And the next steps may be examining potential interactions of social protection with biomedical interventions – such as PrEP and ART for positive adolescents.

This study has one further, and important, advantage. It uses existing interventions that are currently provided by states, NGOs, or families at a large scale. It also demonstrates that social protection combinations remain strongly associated with reductions of HIV-risk behavior independently of a range of predictors of HIV and service access. As a result, the findings show not only that combination social protection is effective in adolescent HIV-risk reduction, but also that it is demonstrably feasible and scalable in real-world African contexts.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council and South African National Research Foundation (RES-062-23-2068), HEARD at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, the South African National Department of Social Development, the Claude Leon Foundation, the John Fell Fund, and the Nuffield Foundation (CPF/41513). Analyses and writing were supported by UNICEF, and we thank Sudhanshu Handa, Patricia Lim Ah Ken, Natalia Winder-Rossi and Tom Fenn for discussion and input. Support was provided to LC by European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013)/ ERC grant agreement n°313421 and the Philip Leverhulme Trust (PLP-2014-095). We thank our fieldwork teams and all participants and their families.

Funding: UK ESRC, UNICEF, NRF (SA), HEARD UKZN, SA Department of Social Development, Claude Leon Foundation, John Fell Fund, Nuffield Foundation, Philip Leverhulme Trust, ERC.

Footnotes

These included: the Launch of the World Bank, UNAIDS and UNICEF Research Network on Structural Drivers and Solutions for HIV. International AIDS Conference, Melbourne 2014, the UNAIDS Planning Coordination Board 2014. Geneva, July, High Level Consultation on Scaling-up Proven Social and Structural Interventions to Prevent HIV Transmission’, Johannesburg, July

This study aimed to examine the effects of social protection in real-world Southern African conditions. In order to maximize utility, we measured cash and care services that are typically provided by governments, NGOs and families. These were identified in consultation with the SA National Departments of Social Development, Basic Education and Health, PEPFARUSAID, UNICEF and Save the Children.

Declaration of Interests: None.

References

- 1.UNICEF . Towards an AIDS-Free Generation – Children and AIDS: Sixth Stocktaking Report. UNICEF; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts C, Seeley J. Addressing gender inequality and intimate partner violence as critical barriers to an effective HIV response in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):19849. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNDP . Discussion paper: cash transfers and HIV-prevention. UN Development Program; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duflo E. Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old-age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review. 2003;17(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson L, Mushati P, Eaton JW, et al. Effects of unconditional and conditional cash transfers on child health and development in Zimbabwe: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9874):1283–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62168-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, Özler B. Effect of a cash transfer program for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1320–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Social Development, SASSA, UNICEF . The South African Child Support Grant Impact Assessment: Evidence from a survey of children, adolescents and their households. UNICEF South Africa; Pretoria: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Handa S, Halpern CT, Pettifor A, Thirumurthy H. The government of Kenya’s cash transfer program reduces the risk of sexual debut among young people age 15-25. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cluver L, Boyes M, Orkin M, Pantelic M, Molwena T, Sherr L. Child-focused state cash transfers and adolescent risk of HIV infenction in South Africa: a propensity score-matched case-control study. Lancet Global Health. 2013;1:e362–70. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cluver L, Orkin M, Boyes M, Sherr L. Cash plus care: social protection cumulatively mitigates HIV-risk behavior among adolescents in South Africa. AIDS. 2014;28(suppl 3):S389–97. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cluver L, Orkin M, Boyes M, Gardner F, Meinck F. Transactional sex amongst AIDS-orphaned and AIDS-affected adolescents predicted by abuse and extreme poverty. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;53(3):336–43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822f0d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adato M, Bassett L. What is the potential of cash transfers to strengthen families affected by HIV and AIDS? A review of the evidence on impacts and key policy debates. International Food Policy Research Institute; Washington DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillespie S, Kadiyala S, Greener R. Is poverty or wealth driving HIV transmission? AIDS. 2007;21(suppl 7):S5–16. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300531.74730.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piot P, Greener R, Russell S. Squaring the circle: AIDS, poverty, and human development. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):1571–5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson J, Yeh E. Transactional sex as a response to risk in Western Kenya. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2011;3(1):35–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinkelman T, Lam D, Leibbrandt M. Linking poverty and income shocks to risky sexual behavior: evidence from a panel study of young adults in Cape Town. S Afr J Econ. 2008;76(suppl 1):S52–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2008.00170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts CH, Foss AM, Hossain M, Zimmerman C, von Simson R, Klot J. Sexual violence and conflict in Africa: prevalence and potential impact on HIV incidence. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(suppl 3):iii93–99. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.044610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNAIDS . UNAIDS report on the global epidemic. Geneva: 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: a retrospective study. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1):E11. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.UNAIDS . A new investment framework for the global HIV response. UN; Geneva: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis NM, Ronan KR, Borduin CM. Multisystemic treatment: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. J Fam Psychol. 18(3):411–9. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.411. 200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivera JA, Sotres-Alvarez D, Habicht JP, et al. Impact of the Mexican program for education, health, and nutrition (Progresa) on rates of growth and anemia in infants and young children: a randomized effectiveness study. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(21):2563–2570. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettifor A, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Young people’s sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS. 2003;19(14):1525–34. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000183129.16830.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shisana O. South African national HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behavior and communication survey, 2005. HSRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christofides NJ, et al. Early adolescent pregnancy increases risk of incident HIV infection in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: a longitudinal study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18585. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Merwe A, Dawes A. Prosocial and antisocial tendencies in children exposed to community violence. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2000;12:19–37. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elgar F, Waschbusch D, Dadds M, Sigvaldason N. Development and validation of a short form of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. J Child Fam Stud. 2007;16(2):243–59. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailly D. Issues related to consent to healthcare decisions in children and adolescents. Archives de pediatrie: organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie. 2010;17:S7–15. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(10)70003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosmer DW, Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant R. Applied Logistic Regression. Third Edition John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrington D, Welsh B. Saving children from a life of crime: Early risk factors and effective interventions. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heise L, Lutz B, Ranganathan M, Watts C. Cash transfers for HIV prevention: Considering their potential. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18615. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]