Abstract

Adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO) allows non-invasive assessment of the cone photoreceptor mosaic. Confocal AOSLO imaging of patients with achromatopsia (ACHM) reveals an altered reflectivity of the remaining cone structure, making identification of the cells more challenging than in normal retinas. Recently, a “split-detector” AOSLO imaging method was shown to enable direct visualization of cone inner segments in patients with ACHM. Several studies have demonstrated gene replacement therapy effective in restoring cone function in animal models of ACHM and human trials are on the horizon, making the ability to reliably assess cone structure increasingly important. Here we sought to examine whether absolute estimates of cone density obtained from split-detector and confocal AOSLO images differed from one another and whether the inter- and intra-observer reliability is significantly different between these modes. These findings provide an important foundation for evaluating the role of these images as tools to assess the efficacy of future gene therapy trials.

XX.1 Introduction

AOSLO enables visualization of the cone photoreceptor mosaic in the living human eye (Dubra et al. 2011; Rossi et al. 2011). Quantitative measurements from such images include cone density (Chui et al. 2008), cone spacing (Duncan et al. 2007; Rossi and Roorda 2010; Cooper et al. 2013) and Voronoi geometry (Baraas et al. 2007). These methods typically rely on identification of individual cones in the image and thus whether this is done manually or via an automated (or semi-automated) process, there is a need to assess the inherent reliability and repeatability of each approach.

Previously we assessed the repeatability of cone density measurements in a population of young healthy individuals using a semi-automated method and found that if repeated images of the same retinal location were precisely aligned, the repeatability was 2.7% (Garrioch et al. 2012). Chiu et al. ( 2013) demonstrated similar repeatability using the same data set and a fully automatic algorithm based on graph theory and dynamic programming. Most recently, we examined the inter-observer and inter-instrument reliability of cone density measurements and found that the inter-observer study’s largest contribution to variability was the subject (95.72%) while the observer’s contribution was only 1.03% (Liu et al. 2014). For the inter-instrument study, we reported an average cone density ICC of between 0.931 and 0.975 (Liu et al. 2014).

These studies are only relevant for individuals with intact cone mosaics and do not apply in conditions such as ACHM, where cone appearance can be greatly altered (Genead et al. 2011; Merino et al. 2011). This makes it difficult to disambiguate cones from other reflective material in the outer retina. Scoles et al. (2014) developed a split-detector AOSLO method to directly visualize cone inner segments in a manner independent of the cone’s waveguide properties (from which the reflective confocal AOSLO signal arises) allowing for easier and more complete visualization of residual cone structure in patients with ACHM. In patients with ACHM, we sought to (1) assess whether estimates of cone density obtained with split-detector AOSLO images differed from those obtained from confocal AOSLO images and (2) determine whether the inter- and intra-observer reliability is significantly different between the two imaging modes. The findings presented here serve as a foundation for subsequent studies aimed at monitoring residual cone structure over time in patients with ACHM.

XX.2 Materials and Methods

XX.2.1 Subjects

All research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and study protocols were approved by IRBs at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Moorfields Eye Hospital. Subjects provided written informed consent after the nature and possible consequences of the study were explained. Images from 7 subjects with molecularly confirmed ACHM (5 with CNGB3 mutations, 2 with CNGA3 mutations) were used in this study (5 males and 2 females, aged 11–64 years). Axial length measurements were obtained from all of the subjects using an IOL Master (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) in order to calculate the lateral scale of each retinal image.

XX.2.2 AOSLO Imaging of the Photoreceptor Mosaic

Each patient’s head was stabilized using a dental impression on a bite bar and both eyes were dilated and cyclopleged using a combination of phenylephrine hydrochloride 2.5% and tropicamide 1%. Images of the photoreceptor mosaic were obtained using 790-nm light with two previously described AOSLOs that allow simultaneous acquisition of confocal and split-detector images as in Figure XX.1 (Scoles et al. 2014). Image sequences (100–200 frames) subtending either 1×1° or 1.5×1.5° were collected between the foveal center and 20° temporal to fixation. Each confocal image sequence was registered to produce a single image with improved signal-to-noise ratio (Dubra and Harvey 2010), with the same transforms applied to the corresponding split-detector image sequence, yielding a second image of the exact same retinal location. From these images, a total of 80 100×100μm areas were cropped for analysis.

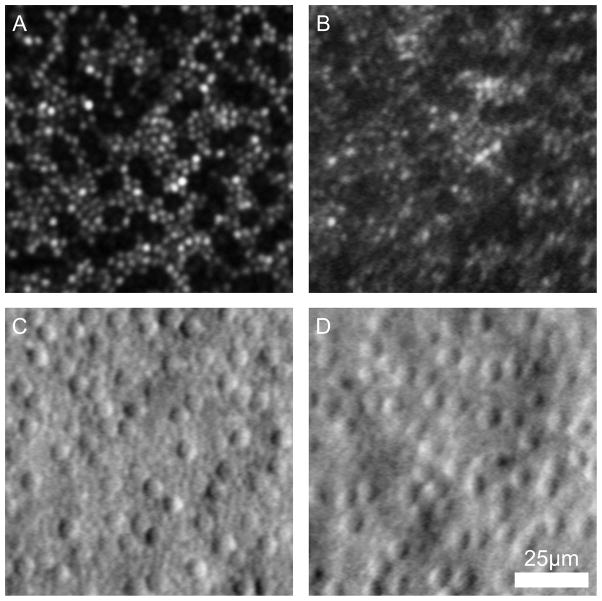

Fig. XX.1.

Confocal (a,b) and split-detector (c,d) AOSLO images from two subjects with ACHM – JC_10069 (a,c) and MM_0005 (b,d).

XX.2.3 Analyzing the Cone Mosaic

The data set consisted of 960 images (80 images, 2 modalities, 3 observers, 2 trials/observer). Three observers with varying familiarity in analyzing AOSLO images reviewed each image and manually identified cones after adjusting the brightness and contrast of the image to assist in determining cone presence. Images were displayed in random order, with the identity and retinal location of the images masked (ensuring any effect of fatigue is captured by the observer’s variance component). The number of cones in the cropped 100×100μm region was divided by its area to derive an estimate of the cone density for that image.

XX.2.4 Statistical Methods

The sample size and other characteristics of this study were chosen using a Monte Carlo simulation with preliminary estimates of unknown quantities estimated on a pilot data set. The objective was to secure the half-width of the 90% CI for the relative contribution to the total variance, such that it is bounded by 1% for observer, trial and image and the half-width of the 90% CI for subjects’ relative contribution to the total variance is not higher than 2.5%. In this simulation study, 1000 repetitions were performed for a variance components model to assess the contribution of subject, mode, observer and trial to overall variability.

XX.3 Results

Highly significant biases prevented further analysis of the variance components model. Table XX.2 reports the fixed effects (regression coefficients) of the parsimonious linear mixed regression model, including both random and fixed effects for predicting cone density values on a natural logarithmic (LN) scale. As each image was assessed 12 times (2 modes, 3 observers, 2 trials) we needed to account for possible correlation between measurements. To do so, our model used three random effects: mode, observer and trial. In addition to the three random effects accounting for within image correlation, we investigated three fixed effects of mode, observer and trial, as well as the two-way interactions and the three-way interaction. Statistical significance was declared at 5%. We found that the three-way interaction between mode, observer and trial was not significant (P=0.194). The two-way interaction between mode and trial was also not significant (P=0.479). The interactions between observer and trial and between observer and mode were highly significant (P<0.0001).

Table XX.2.

Cone Density Measurements for Each Observer

| - | Observer 1 | Observer 2 | Observer 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode (Trial) | Estimate | Std. Err. | Estimate | Std. Err. | Estimate | Std. Err. |

| Confocal (1) | 8.34 | 0.062 | 8.32 | 0.058 | 8.32 | 0.058 |

| Confocal (2) | 8.43 | 0.057 | 8.31 | 0.058 | 8.31 | 0.058 |

| Split (1) | 8.28 | 0.071 | 8.16 | 0.068 | 8.16 | 0.068 |

| Split (2) | 8.31 | 0.067 | 8.16 | 0.068 | 8.16 | 0.068 |

The linear mixed model used to build Table XX.2 absorbed information from all 960 observations. The presence of significant interactions with the observer prevents easily explaining the content of Table XX.1. To simplify the explanation of the regression modeling we fitted separate models for each observer, allowing us to interpret findings separately for each observer. Table XX.2 reports the estimates of mean LN(cone density) separately for each observer. Observer 1 had a significantly different interaction between trial and mode (P=0.006), precluding investigation of further interactions for this observer. The interactions between mode and trial (P=0.951) and the main effect of trial (P=0.447) were not significant for observer 2. Only the effect of mode was significant for observer 2 (P<0.0001). The interaction between mode and trial was not significant for observer 3 (P=0.632), nor was the main effect of mode (P=0.160). Surprisingly, we observed a strong effect of trial (P<0.0001).

Table XX.1.

Fixed Effects for All Observers

| Variable | Estimate | Std.Err. | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 8.35 | 0.060 | 138.53* |

| Mode=Split | −0.083 | 0.035 | −2.34* |

| Trial=2 | 0.061 | 0.016 | 3.78* |

| Obs=2 | −0.030 | 0.020 | −1.47 |

| Obs=3 | −0.119 | 0.029 | −4.04* |

| Trial=2:Obs=2 | −0.068 | 0.022 | −3.08* |

| Trial=2:Obs=3 | 0.035 | 0.022 | 1.59 |

| Mode=Split:Obs=2 | −0.074 | 0.022 | −3.34* |

| Mode=Split:Obs=3 | 0.025 | 0.022 | 1.12 |

The model intercept corresponds to the expected LN(cone density) for the confocal mode, observer=1 and trial=1.

Statistically significant

This result indicates that the observers’ counts differ for different trials and modes, such that one observer may have different responses between modes and another observer may show no difference. Likewise, one observer may have different responses between trials with another observer showing no difference.

XX.4 Discussion

The results of the linear mixed regression model analysis demonstrated a strong effect of observer in cone counting in images from patients with ACHM using two different imaging modalities. This strong observer effect prevents further analysis of the reliability and repeatability of cone measurements in these retinas. Upon further analysis two of three observers showed a strong effect of trial (independent effect for one and interacting with mode for another), indicating that they were not able to consistently identify the same number of cells in the image set between two trials, with observer 1 showing an effect in the interaction between trial and mode. Observer 2, however, showed no effect of trial and the effect of mode indicates a difference between the confocal and split-detector measurements for this observer. Varying experience working with ACHM images (observer 2 had the most and observer 3 the least) may partially explain these results – thus analysis of diseased retinas may require a more experienced observer than analysis of cone structure in normal retinas. This result demonstrates the need for more experienced observers to analyze images of diseased retinas and development of automated methods for split-detector analysis.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by grants from the The Wellcome Trust [099173/Z/12/Z], National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, NIH grants R01EY017607, R24EY022023, P30EY001931, C06RR016511, & UL1TR000055, Fight For Sight (UK), Moorfields Eye Hospital Special Trustees, the Foundation Fighting Blindness (USA), RP Fighting Blindness, an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB). Dr. Michaelides is supported by an FFB Career Development Award.

References

- Baraas RC, Carroll J, Gunther KL, et al. Adaptive optics retinal imaging reveals S-cone dystrophy in tritan color-vision deficiency. J Opt Soc Am A. 2007;24:1438–1446. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.001438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SJ, Lokhnygina Y, Dubis AM, et al. Automatic cone photoreceptor segmentation using graph theory and dynamic programming. Biomed Opt Express. 2013;4:924–937. doi: 10.1364/BOE.4.000924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui TYP, Song HX, Burns SA. Individual variations in human cone photoreceptor packing density: variations with refractive error. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4679–4687. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RF, Langlo CS, Dubra A, et al. Automatic detection of modal spacing (Yellott’s ring) in adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscope images. Ophthal Physl Opt. 2013;33:540–549. doi: 10.1111/opo.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubra A, Harvey Z. Registration of 2D Images from Fast Scanning Ophthalmic Instruments. The 4th International Workshop on Biomedical Image Registration Lübeck; Germany. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dubra A, Sulai Y, Norris JL, et al. Noninvasive imaging of the human rod photoreceptor mosaic using a confocal adaptive optics scanning ophthalmoscope. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:1864–1876. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JL, Zhang Y, Gandhi J, et al. High-resolution imaging with adaptive optics in patients with inherited retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3283–3291. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrioch R, Langlo C, Dubis AM, et al. Repeatability of in vivo parafoveal cone density and spacing measurements. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:632–643. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182540562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genead MA, Fishman GA, Rha J, et al. Photoreceptor structure and function in patients with congenital achromatopsia. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2011;52:7298–7308. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BS, Tarima S, Visotcky A, et al. The reliability of parafoveal cone density measurements. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:1126–1131. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino D, Duncan JL, Tiruveedhula P, et al. Observation of cone and rod photoreceptors in normal subjects and patients using a new generation adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:2189–2201. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.002189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi EA, Roorda A. The relationship between visual resolution and cone spacing in the human fovea. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:156–157. doi: 10.1038/nn.2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi EA, Chung M, Dubra A, et al. Imaging retinal mosaics in the living eye. Eye. 2011;25:301–308. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoles D, Sulai YN, Langlo CS, et al. In vivo imaging of human cone photoreceptor inner segments. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2014;55:4244–4251. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]