Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate the clinical features of systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) complicated with Evans syndrome (ES).

We conducted a retrospective case–control study to compare the clinical and laboratory features of age- and gender-matched lupus patients with and without ES in 1:3 ratios.

In 5724 hospitalized SLE patients, we identified 27 (0.47%, 22 women and 5 men, average age 34.2 years) SLE patients complicated with ES. Fifteen patients (55.6%) presented with hematologic abnormalities initially, including 6 (22.2%) cases of isolated ITP, 4 (14.8%) cases of isolated AIHA, and 5 (18.5%) cases of classical ES. The median intervals between hematological presentations the diagnosis of SLE was 36 months (range 0–252). ES developed after the SLE diagnosis in 4 patients (14.8%), and concomitantly with SLE diagnosis in 8 patients (29.6%). Systemic involvements are frequently observed in SLE patients with ES, including fever (55.6%), serositis (51.9%), hair loss (40.7%), lupus nephritis (37%), Raynaud phenomenon (33.3%), neuropsychiatric (33.3%) and pulmonary involvement (25.9%), and photosensitivity (25.9%). The incidence of photosensitivity, hypocomplementemia, elevated serum IgG level, and lupus nephritis in patients with ES or without ES was 25.9% vs 6.2% (P = 0.007), 88.9% vs 67.1% (P = 0.029), 48.1% vs 24.4% (P = 0.021), and 37% vs 64.2% (P = 0.013), respectively. Twenty-five (92.6%) patients achieved improvement following treatment of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants as well as splenectomy, whereas 6 patients experienced the relapse and 1 patient died from renal failure during the follow-up.

ES is a relatively rare complication of SLE. Photosensitivity, hypocomplementemia, and elevated serum IgG level were frequently observed in ES patients, but lupus nephritis was less observed. More than half of patients presented with hematological manifestation at onset, and progress to typical lupus over months to years. Therefore, monitoring with antoantibodies profile as well as nonhematological presentations are necessary for patients with ITP and (or) AIHA.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized with multisystem involvement as well as broad spectrum of serum autoantibodies. The hematologic manifestations are commonly presented in lupus patients, including leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and even pancytopenia. Evans syndrome (ES) is a rare hematological disease characterized by the simultaneous or sequential occurrence of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) and immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).1,2 The management of ES is challenging: despite aggressive treatment, relapses are common in ES patients, with median 3 to 5 episodes of ITP and 2 to 3 episodes of AIHA.3 The characteristics of ES in SLE patients are poorly understood, with anecdotal case reports and case series.4 In this study, we reviewed retrospectively the clinical features of age- and sex-matched lupus patients complicated with or without ES, and explored the characteristics of ES in lupus patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Medical records of 5724 SLE patients admitted to the Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) from January 2004 to July 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. All patients fulfilled the 2009 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinic revision of the American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for SLE.5 Disease activity was recorded at the time of the hematological presentation using the SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI).6 ES was defined as the presence of AIHA and ITP simultaneously or sequentially.7 Concomitant of other autoimmune disease, including antiphospholipid syndrome and Sjögren's syndrome, was defined by consensus criteria.8,9 Complete blood count, direct and indirect hyperbilirubinemia, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), direct antiglobulin (Coombs’) test, complements, immunoglobulins, antinuclear antibodies, and antiphospholipid antibodies were evaluated. Peripheral blood smear and bone marrow examination were evaluated in some patients to confirm the diagnosis of ES. Nonautoimmune thrombocytopenia and/or hemolytic anemia, including paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), were excluded. Furthermore, lymphoproliferative disorders were ruled out based on physical examination, peripheral blood smear, bone marrow examination, and abdominal ultrasonography or computer tomography when indicated to assess splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy.

The following criteria were used to evaluate the treatment response.10,11 For AIHA, complete response (CR) was defined as a hemoglobin level above 120 g/L in the absence of any transfusion, and without features of hemolysis (normal bilirubin, LDH levels, and reticulocyte count). Partial response (PR) was defined as a rise in hemoglobin levels of >2 g/dL, without or reduced transfusion requirement, and improvement of clinical and laboratory signs of hemolysis. For ITP, CR was defined as a normal platelet count (i.e., >100 × 109/L) and PR as a platelet count >50 × 109/L with at least a 2-fold increase of the pretreatment count. Those patients who did not achieve CR or PR were grouped into no response (NR).

The local institutional review board approved this study. Because the study was based on a review of medical records obtained for clinical purposes, the requirement for written informed consent was waived, and patients’ records/information were anonymized before analysis.

Statistical Analyses

SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago) was used to statistically analyze the data. Numerical data and categorical data were expressed as median (range) and percentage, respectively. The significance was estimated by Student's t-test, Pearson's chi-square, or Fisher's exact test (when expected frequencies were <5). P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

General Data

In 5724 hospitalized SLE patients, we identified 27 (0.47 %) SLE patients complicated with ES, who were all Han Chinese ancestry, with median age of 34.2 (range 15–62) years. Twenty-two patients (81.5%) were women. As the controls, 81 age- and sex-matched hospitalized SLE patients without ES were randomly selected from the same period. Four (14.8%) and 4 (14.8%) patients were concomitant with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and Sjögren syndrome (SS), respectively.

Fifteen patients (55.6%, 4 men and 11 women) presented with hematologic abnormalities initially, including 6 (22.2%) cases of isolated ITP, 4 (14.8%) cases of isolated AIHA, and 5 (18.5%) cases of classical ES. The median intervals between hematological presentations the diagnosis of SLE were 36 months (range 0–252), with 48 months (ranged 0–122), 16.5 months (range 6–252), and 37 months (range 1–76) in isolated ITP, isolated AIHA, and ES patients, respectively. Four cases (14.8%) developed ES after the diagnosis of SLE, with a median duration of 24.3 (range 1–55) months, and ES was diagnosed concomitantly with SLE in 8 patients (29.6%).

Clinical Manifestations

Systemic involvements are frequently observed in SLE patients with ES, including fever (15/27, 55.6%), lupus nephritis (10/27, 37%), serositis (14/27, 51.9%), hair loss (11/27,40.7%), photosensitivity (7/27, 25.9%), Raynaud phenomenon (9/27, 33.3%), malar rash (5/27, 18.5%), neuropsychiatric manifestations (9/27, 33.3%), pulmonary involvement (7/27, 25.9%), and cutaneous vasculits (3/27, 11.1%). The median SLEDAI at the onset of ES was 10 (range 3–33).

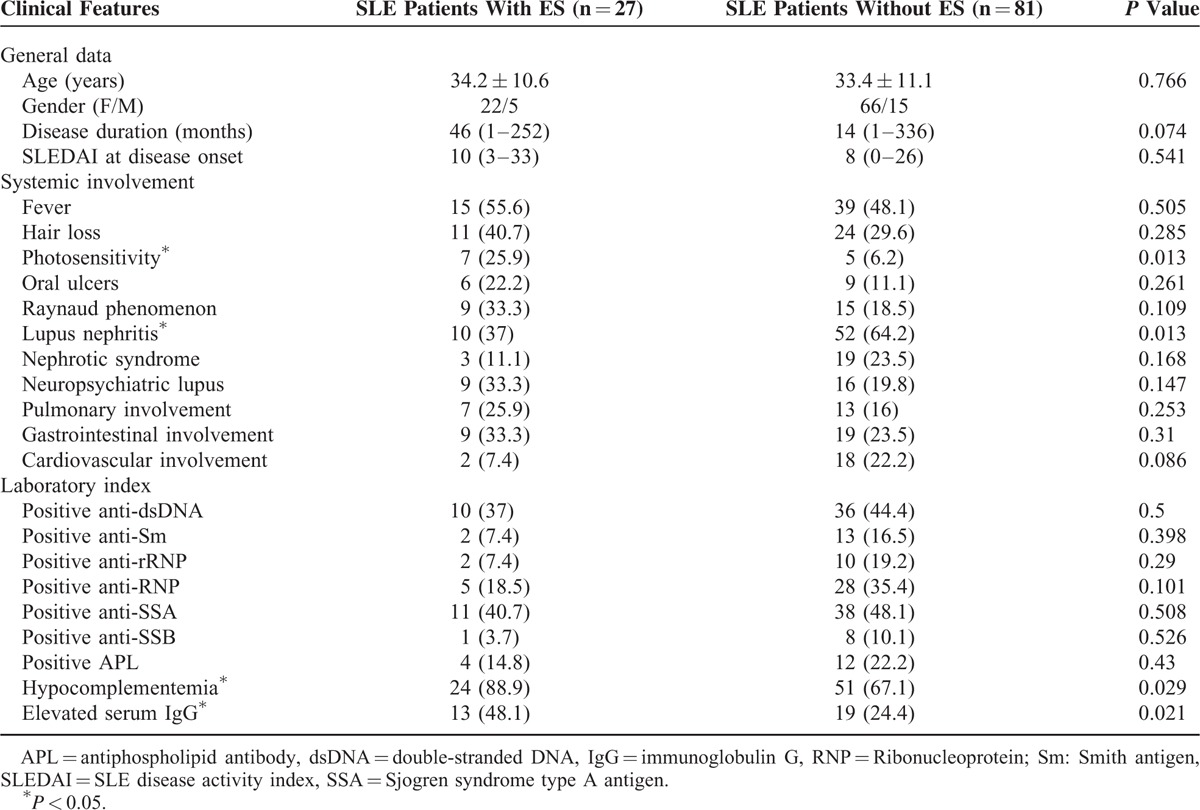

Compared with SLE patients without ES, the incidence of lupus nephritis was significantly lower in SLE patients with ES (37% vs 64.2%, P = 0.013) (Table 1). But photosensitivity (25.9% vs 6.2%, P = 0.007) was more frequently (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparisons of Systemic Involvement and Laboratory Findings Comparison of SLE Patients With Evans Syndrome (ES) and Without ES

Laboratory Findings

The median hemoglobin level of ES patients was 50 (range 29–105) g/L, including mild anemia (90–120 g/L) in 2 cases, moderate anemia (60–90 g/L) in 6 cases, and severe anemia (30–60 g/L) in 19 cases. Median platelet count of these patients was 10 × 109 (range 0–79 × 109)/L. The severity of thrombocytopenia: moderate (50–99 × 109/L in 3 cases, severe (20–50 × 109/L) in 6 cases, and very severe (less than 20 × 109/L) in 18 cases. 23 (85.2%) patients were proven to have a positive direct Coombs’ test result. Four patients had a negative Coombs’ test result, but demonstrated with obvious hemolysis. Ultrasound examination found hepatosplenomegaly in 17 cases.

ANA was positive in all ES patients. Elevated titer of serum anti-dsDNA antibody was found in 10 cases (37%). Serum anti-Sm antibody was positive in 2 (7.4%), anti-SSA in 11 (40.7%), anti-SSB in 1 (3.7%), anti-rRNP in 2 (7.4%), and anti-RNP antibody in 5 (18.5%) cases, respectively. Hypocomplementemia and elevated serum IgG level were found in 24 (88.9%) and 13 (48.1%) cases, respectively. Antiplatelet antibody was positive in 5 patients (18.5%). Antiphospholipid antibodies (APLs) including IgG-type anti-cardiolipin antibodies (2/27, 7.4%), IgG-type anti-β2 GP1 antibodies (3/27, 11.1%), and lupus anticoagulants (6/27, 22.2%) were detected in this cohort.

Compared with SLE patients without ES, hypocomplementemia (88.9% vs 67.1%, P = 0.029) and elevated serum IgG level (48.1% vs 24.4%, P = 0.021) were more frequently in patients with ES (Table 1).

Treatment and Prognosis

All 27 patients received glucocorticoid (GC) combined with immunosuppressant treatment. Sixteen patients (59.3%) were treated by methylprednisolone pulse therapy (0.5–1 g methylprednisolone per day for 3–5 consecutive days). Cyclophosphamide was the most commonly used immunosuppressant (74%, 20/27), followed by cyclosporin (37%, 10/27), mycophenolate mofetil (18.5%, 5/27), tacrolimus (14.8%, 4 /27), and tripterygium wilfordii glycoside (7.4%, 2/27). In addition, 19 patients received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and 2 patients took plasmapheresis. For AIHA, 10 patients (37%) achieved CR, 15 patients (55.5%) achieved PR, whereas 2 patients (7.4%) were considered as NR. For ITP, 16 patients (59.3%) achieved CR, 8 patients (29.6%) achieved PR, whereas 3 patients (11.1%) were considered as NR. Overall, 8 patients achieved the CR of both AIHA and ITP, 1 patient who lost follow-up achieved the NR of both AIHA and ITP, and 1 patient died from multiple organ failure. During a median follow-up of 27.7 (range 1–66) months, 6 patients experienced the relapse, and 1 patient died from renal failure.

DISCUSSION

Hematological disorders are common features of SLE. Almost all SLE patients suffer cytopenia affecting 1 or more blood cell lineages throughout the course. Isolated hematological disorders such as ITP or AIHA could be the initial manifestation of SLE, preceding other manifestations by months or years. AIHA occurred in ∼5% to 10% SLE patients,7,12 and thrombocytopenia may be present in up to 20% to 40% SLE patients.13 Studies have showed that ES seems to be a rare manifestation in SLE, and 3% to 15% ES patients would develop SLE during the follow-up.14,15 The clinical features of lupus patients complicated with ES are limited. Currently, only 1 study reports the clinical presentation and outcome of ES in Brazilian SLE patients.15 In our study, the prevalence of ES was ∼0.47% in SLE, demonstrating the rarity of this condition.

We also showed that half (55.6%) of lupus patients complicated with ES initially presented with hematologic abnormalities (ITP/AIHA), whom usually had undetectable or low-titer autoantibodies. These patients did not fulfill the established criteria of lupus and were misdiagnosed or even treated improperly at the onset. During the course, autoantibodies such as anti-Smith antibody or anti-dsDNA antibody, as well as the nonhematological features presented. Notable, the intervals between the initial hematological presentations and the final diagnosis of SLE could be long (median intervals 36 months, with range 0–252 months). Collectively, patients with ITP or AIHA should be closely monitored with antoantibodies profile and nonhematological presentations, especially during the first 3 years.

We further compare the nonhematological feature of SLE patients with ES and without ES. SLE patients with ES showed more frequently with photosensitivity (25.9% vs 6.2%, P = 0.013). Additionally, active features of SLE including hair loss (40.7% vs 29.6%), Raynaud phenomenon (33.3% vs 18.5%), oral ulcers (22.2% vs 11.2%), neuropsychiatric (33.3% vs 19.8%), pulmonary (25.9% vs 16%), and gastrointestinal involvement (33.5% vs 23.5%) were more frequently presented in lupus patients with ES, but without statistically significance. Furthermore, SLE patients with ES presented more frequently with hypocomplementemia and elevated serum IgG level. However, no significant difference of disease activity assessed by SLEDAI was found between 2 groups. Surprisingly, the incidence of lupus nephritis was much lower in SLE patients with ES (37% vs 64.2%, P = 0.013), which is inconsistent with the previous report.15 Due to the small sample size of this study, we did not identify any risk factors of ES. A large-scale study is warranty to confirm the association of these clinical features with ES.

The pathogenesis of ES complicated with SLE still remains unknown. Autoantibodies against erythrocyte and thrombocyte are frequently found in SLE patients complicated with ES, suggesting both SLE and ES are immune-mediated diseases. Previous studies showed that antiphospholipid antibodies (APLs) including anticardiolipin antibody and anti-β2 glycoprotein-I antibody were found more frequently in SLE patients complicated with AIHA and (or) ITP, which suggested that these molecules might involve in etiology of ES in SLE.13 It was reported that ES was associated with T-cell abnormalities. A decrease in CD4 cells and CD4/CD8 cells, as well as an increase in CD8 cells was found in ES patients.16 However, a case of ES with IgM deficiency and lymphopenia had a reduction of CD4 and CD8 cells.17 Further studies showed that CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell (Treg) in patients with ES were significantly decreased in active disease and elevated in remission, which is suggestive that Treg dysregulation plays a key role in the pathogensis of ES.18,19

Patients with ES typically respond well to glucocorticoids treatment, but unlike ITP and AIHA, ES might be protracted and more likely to relapse, especially when glucocorticoids were tapered or ceased.11,20 No consensus treatment guideline is currently available. The most commonly used first-line therapy is corticosteroids and/or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). For refractory cases, danazol, immunosuppressants, splenectomy, and plasma exchange are used. Rituximab can specifically recognize and eradicate the CD20-expressing B cells and has become one of the standard second-line drugs for refractory or relapsed primary ITP/AIHA treatment. In recent years, the effectiveness of Rituximab in patients with refractory and recurrent ES has been confirmed.21,22 In addition, an allogeneic and autologous stem cell transplant (SCT) offers the chance of long-term cure for very severe and refractory cases.23 In our study, all patients were treated with glucocorticoid, and more than half of patients (59.3%) were treated with intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy. One or more immunosuppressants were used in almost all patients. However, 6 patients relapsed when corticosteroids are tapered or stopped during the follow-up. This result highlighted the combination with immunosuppressants could permit tapering glucocorticoid dose rapidly and decrease the risk of relapse.

Our study has several potential limitations. As our hospital is a nationwide referral center of diagnosis and evaluation for the difficult and rare rheumatic diseases, which may result in more severe cases enrolled in our study, we cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias in study population. Moreover, with the limited number of cases in the previous articles and our study, we did not identify more characteristic presentations to predict ES in lupus patients.

In summary, ES is a rare complication of lupus and is present in active lupus. Photosensitivity, hypocomplementemia, and elevated serum IgG level were frequently observed in ES patients, but lupus nephritis was less observed. More than half of patients presented with hematological manifestation at onset and progress to typical lupus over months to years. Therefore, monitoring with antoantibodies profile as well as nonhematological presentations are necessary for patients with ITP and (or) AIHA.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AIHA = autoimmune hemolytic anemia, ANA = antinuclear antibody, APLs = antiphospholipid antibodies, CR = complete response, ES = Evans syndrome, ITP = immune thrombocytopenia, IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin, NR = no response, PR = partial response, SCT = stem cell transplant, SLE = systemic lupus erythematous, SLEDAI = SLE disease activity index.

Funding: this study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants (81302590, 81571598), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7152120), and Chinese Medical Association (12040670367).

Author contributions: all authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study. LZ, LW, and XW acquired the data. LZ performed the data analysis and interpretation and wrote the manuscript. WZ provided critical revisions to the manuscript. JL, HC, and YZ also critically reviewed the manuscript and provided valuable input. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Savasan S, Warrier I, Ravindranath Y. The spectrum of Evans’ syndrome. Arch Dis Child 1997; 77:245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhingra KK, Jain D, Mandal S, et al. Evans syndrome: a study of six cases with review of literature. Hematology 2008; 13:356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norton A, Roberts I. Management of Evans syndrome. Br J Haematol 2006; 132:125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laksmi PW, Imanta G, Sukmana N, et al. Evans syndrome manifestation in systemic lupus erythematosus male. Acta Med Indones 2004; 36:215–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:2677–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, et al. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum 1992; 35:630–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokori SI, Ioannidis JP, Voulgarelis M, et al. Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med 2000; 108:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002; 61:554–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baek SW, Lee MW, Ryu HW, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a retrospective analysis of 32 cases. Korean J Hematol 2011; 46:111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michel M, Chanet V, Dechartres A, et al. The spectrum of Evans syndrome in adults: new insight into the disease based on the analysis of 68 cases. Blood 2009; 114:3167–3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durán S, Apte M, Alarcón GS, et al. Features associated with, and the impact of, hemolytic anemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: LX, results from a multiethnic cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59:1332–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sultan SM, Begum S, Isenberg DA. Prevalence, patterns of disease and outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus who develop severe haematological problems. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003; 42:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karpatkin S. Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 1980; 56:329–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costallat GL, Appenzeller S, Costallat LT. Evans syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical presentation and outcome. Joint Bone Spine 2012; 79:362–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Herrod H, Pui CH, et al. Immunoregulatory abnormalities in Evans syndrome. Am J Hematol 1983; 15:381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karakantza M, Mouzaki A, Theodoropoulou M, et al. Th1 and Th2 cytokines in a patient with Evans’ syndrome and profound lymphopenia. Br J Haematol 2000; 110:968–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giovannetti A, Pierdominici M, Esposito A, et al. Progressive derangement of the T cell compartment in a case of Evans syndrome. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2008; 145:258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu B, Zhao H, Poon MC, et al. Abnormality of CD4 (+) CD25 (+) regulatory T cells in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Eur J Haematol 2007; 78:139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng SC. Evans syndrome: a report on 12 patients. Clin Lab Haematol 1992; 14:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamimoto Y, Horiuchi T, Tsukamoto H, et al. A dose-escalation study of rituximab for treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus and Evans 'syndrome: immunological analysis of B cells, T cells and cytokines. Rheumatology 2008; 47:821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kittaka K, Dobashi H, Baba N, et al. A case of Evans syndrome combined with systemic lupus erythematosus successfully treated with rituximab. Scand J Rheumatol 2008; 37:390–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passweg JR. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for immune thrombopenia and other refractory autoimmune cytopenias. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2004; 17:305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]