Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex mental disorder and can severely interfere with the normal life of the affected people. Previous studies have examined the association of PTSD with genetic variants in multiple dopaminergic genes with inconsistent results.

To perform a systematic literature search and conduct meta-analysis to examine whether genetic variants in the dopaminergic system is associated with PTSD.

PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Google Scholar, and HuGE.

The studies included subjects who had been screened for the presence of PTSD; the studies provided data for genetic variants of genes involved in the dopaminergic system; the outcomes of interest included diagnosis status of PTSD; and the studies were case–control studies.

Odds ratio was used as a measure of association. We used random-effects model in all the meta-analyses. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using I2, and publication bias was evaluated using Egger test. Findings from meta-analyses were confirmed using random-effects meta-analyses under the framework of generalized linear model (GLM).

A total of 19 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in our analyses. We found that rs1800497 in DRD2 was significantly associated with PTSD (OR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.15–3.33; P = 0.014). The 3′-UTR variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) in SLC6A3 also showed significant association with PTSD (OR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.12–2.35; P = 0.010), but there was no association of rs4680 in COMT with PTSD (P = 0.595).

Sample size is limited for some studies; type and severity of traumatic events varied across studies; we could not control for potential confounding factors, such as age at traumatic events and gender; and we could not examine gene–environment interaction due to lack of data.

We found that rs1800497 in DRD2 and the VNTR in SLC6A3 showed significant association with PTSD. Future studies controlling for confounding factors, with large sample sizes and more homogeneous traumatic exposure, are needed to validate the findings from this study.

INTRODUCTION

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex mental disorder following a severe traumatic experience, and is usually accompanied by an intense sense of terror, fear, and helplessness.1 PTSD can severely interfere with the normal life of the affected people. About 7% to 8% of the USA population (∼8 million adults) will have PTSD at some time point during life, and a higher percentage of the Gulf War and Vietnam War veterans have PTSD.2 PTSD can result from various types of traumatic incidents such as war, urban violence, and natural disasters (e.g., earthquake and flood). Although increasing knowledge for PTSD has been obtained using sophisticated genetic and brain-imaging techniques,3 the exact underlying pathophysiology remains to be ambiguous and there is no effective treatment for PTSD available now.

The dopaminergic system consists of multiple genes involved in the biosynthesis, transport, degradation, transmission, and signaling transduction of the neurotransmitter dopamine, such as the solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 3 (SLC6A3 or DAT1), dopamine degradation enzyme catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT), and dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2).4 The dopaminergic signaling system plays important roles in many neurological processes such as rewarding and motivating, memory and learning, and fine motor control.5 Abnormal dopaminergic signaling and function is associated with many neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).6,7

Dysregulated dopamine is also associated with various PTSD symptoms related to attention, vigilance, arousal, and sleep.8 Genetic variations in the dopaminergic system that are involved in dopamine synthesis, binding affinity, and signaling transduction may have influence on the ability to deal with stress stimuli in subjects who have been exposed to traumatic events.9 Neuroimaging studies indicated that the dopamine system is usually dysregulated in PTSD patients to counteract or worsen the crisis response to the stressful stimuli.10 In addition, dopamine can be converted to norepinephrine by dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) enzyme.11 Exposure to continued high stress leads to elevated norepinephrine concentration in cerebrospinal fluid and overactivation of norepinephrine receptors, which is associated with nightmares and flashbacks that are frequently experienced in the individuals with PTSD.12,13

Previous studies have examined the association of PTSD with genetic variants in several dopaminergic genes, with inconsistent results.14 To the best of our knowledge, no meta-analysis has been performed to pool results from the existing literature. Therefore, in this study, we performed meta-analyses of the association of PTSD with multiple genetic variants in DRD2, SLC6A3, COMT, and DBH.

METHOD

Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used to determine study eligibility: The studies included subjects who had been screened for the presence of PTSD; the studies provided data for genetic variants of genes involved in the dopaminergic system; the outcomes of interest included diagnosis status of PTSD; and the studies were case–control studies.

Search Strategy

We performed a systematic literature search in Pubmed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Google Scholar, and HuGE (a navigator for human genome epidemiology) for papers published before May 31, 2015. The keywords used in the literature search can be found in the online supplementary file. We retrieved all potential publications to evaluate eligibility. We also manually searched the references of all relevant studies to screen studies that might have been missed. The literature search was performed independently by 2 authors (YB and JY) and was limited to studies published in English. Any discrepancies were resolved through a group discussion.

Data Extraction

Following a prespecified protocol for data extraction, 2 authors (LL and JY) independently extracted the following data: name of the 1st author, year of publication, characteristic of the participants including sample size, age, gender, race/country of participants, diagnostic instrument for PTSD, type of PTSD (lifetime vs current), type of traumatic events exposure, gene(s) studied, genotype data for patients with and without PTSD, or odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Any discrepancies were resolved in a group meeting.

Data Analysis

OR was used as a measure to assess the association between genetic variants in the dopaminergic system and PTSD diagnosis. In all meta-analyses, we used random-effects models to calculate OR and the corresponding 95% CI. Between-study heterogeneity and publication bias was assessed using I2 and a funnel plot and Egger test, respectively.

Traditional meta-analysis assumes approximate normal within-study likelihood and treats the standard errors as known. This approach has several disadvantages such as failing to account for the correlation between the estimate and the standard error.15 It is especially problematic for sparse data when there are groups within individual studies that have few or even zero events. In such cases, standard errors are highly variable or undefined. Continuity corrections could influence the results and conclusions,16,17 and noncontinuity correction methods often assume homogeneity among the studies. Therefore, to confirm our findings, we further employed a novel statistical method and conducted random-effects meta-analyses in the framework of a generalized linear model (GLM) using the metafor package in R.15

Sensitivity Analysis

In the meta-analysis for DRD2, there are several studies in which subjects in the control group did not experience traumatic events. We repeated the analysis by excluding these studies. Since the type of trauma experienced by the subjects varied across studies, we also performed separate meta-analyses by focusing on combat traumatic events which were adopted in many of the included studies. We also analyzed the association by ethnicity, where possible. Furthermore, we performed additional meta-analyses by including only studies that satisfied Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the control. And finally, we did separate analysis by excluding studies which assessed lifetime PTSD instead of current PTSD.

As our study used a systematic review and meta-analysis, ethical approval of this study is not required. This work was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.18 All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), R (www.R-project.org), Matlab 8.1.0.604 (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA), and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Selection and Characteristics

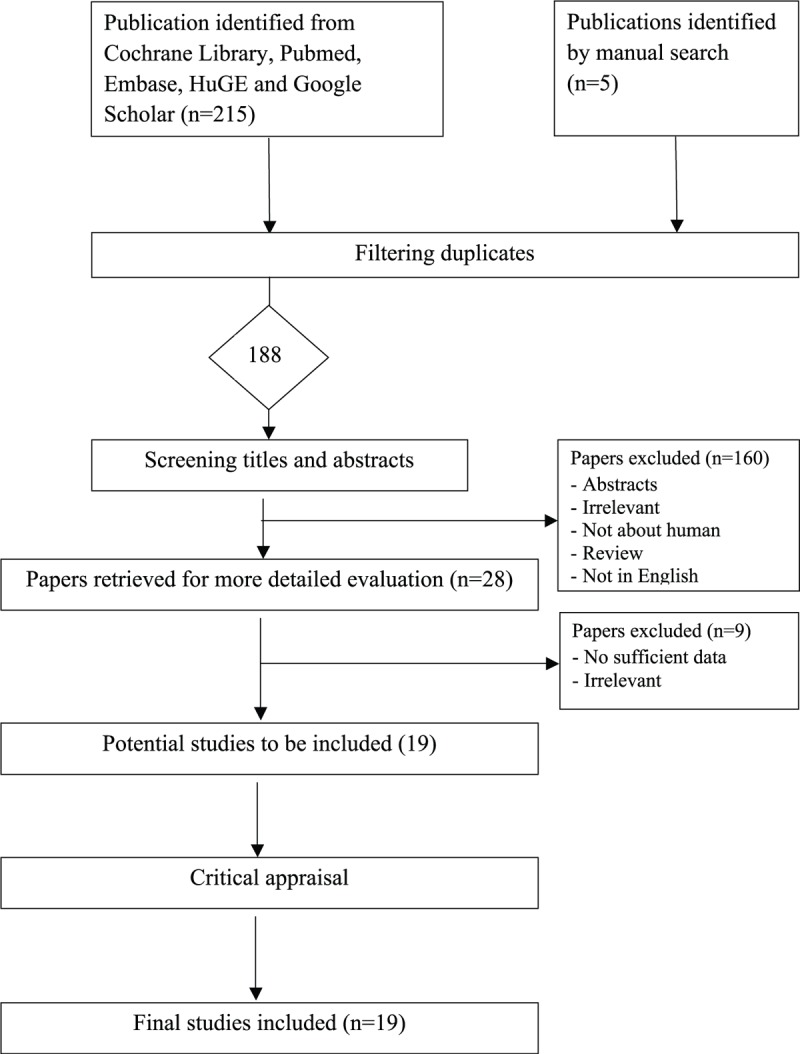

Figure 1 shows the literature search and selection of eligible studies. Our initial search identified a total of 188 potential publications. We excluded 160 publications either because they were irrelevant, review or meta-analysis, not in English, not about human subjects, or because they were published as abstracts. Of the remaining 28 studies which were retrieved for more detailed evaluations, we further excluded an additional 9 studies because they were insufficient data, or there were irrelevant. This led to 19 potentially relevant publications to be included in our analyses.19–37

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the selection process of the studies included in the meta-analyses. Note: Please see the Methods section for additional details.

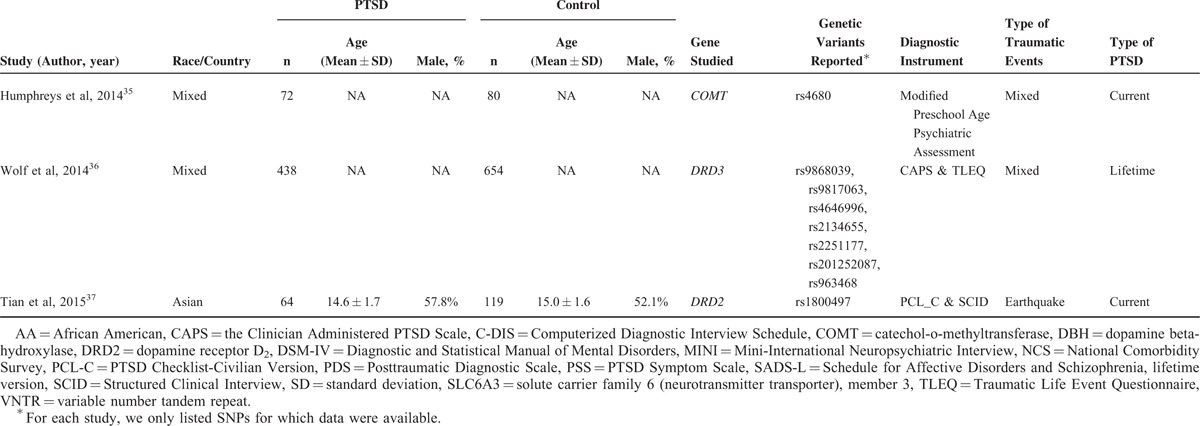

All qualified publications were published since 1991 and had sample sizes ranging from 56 to 1749 (Table 1 ). Of these 19 studies, 6 studies provided data for DRD2,19–21,23,26,37 3 for SLC6A3,22,30,32 5 for COMT,27,29,31,34,35 and 2 for DBH.24,28 These studies were included in the corresponding meta-analyses. The combined study included 1752 subjects in meta-analysis for rs1800497 in DRD2, 600 for the variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) in SLC6A3, 1044 for rs4680 in COMT, and 394 for rs161115 in DBH. For meta-analysis of rs1800497 in DRD2, the VNTR in SLC6A3, rs6480 in COMT, and rs161115 in DBH, the reference genotype is A2A2, 10R10R, VM+MM, and TC+CC, respectively.

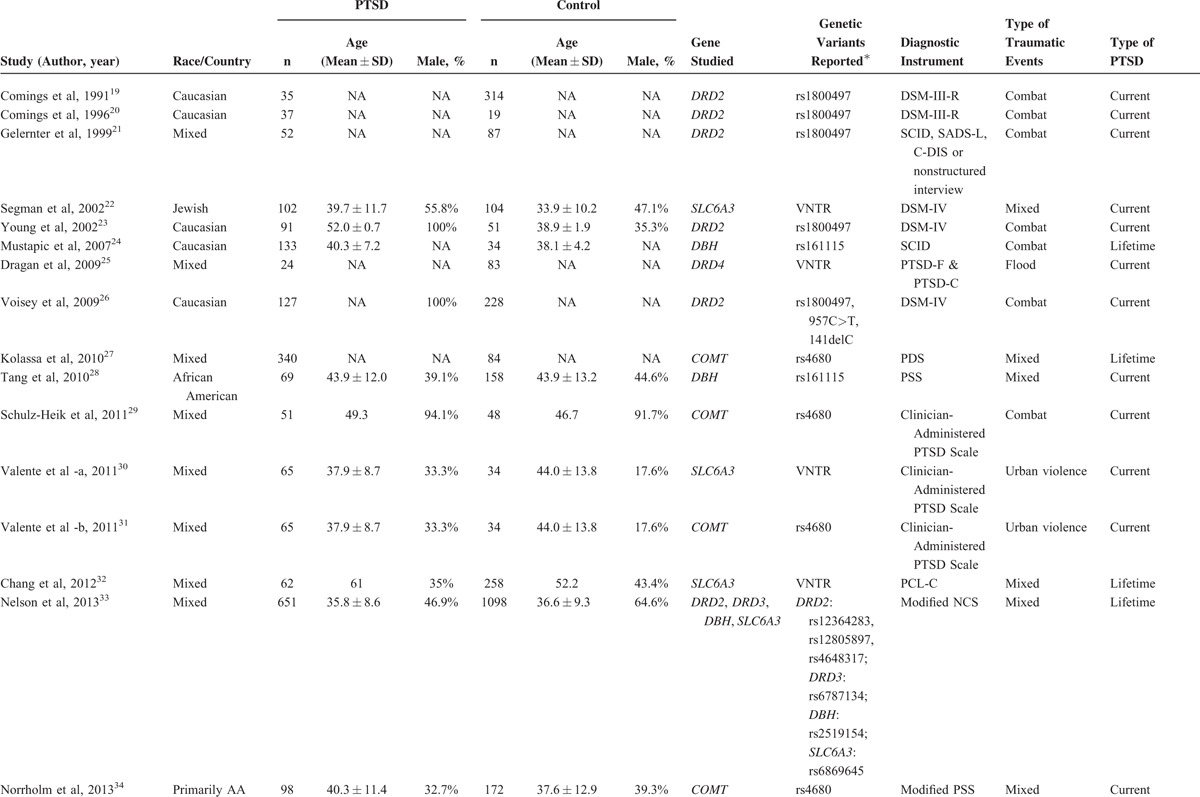

TABLE 1.

Basic Characteristics of all Studies

One study provided association results for multiple SNPs in DRD2, DRD3, SLC6A3, and DBH,33 1 study provided data for 2 additional genetic variants in DRD2.26 One study provided association results for multiple SNPs in DRD3.36 And another studies provided data for a VNTR in DRD4.25

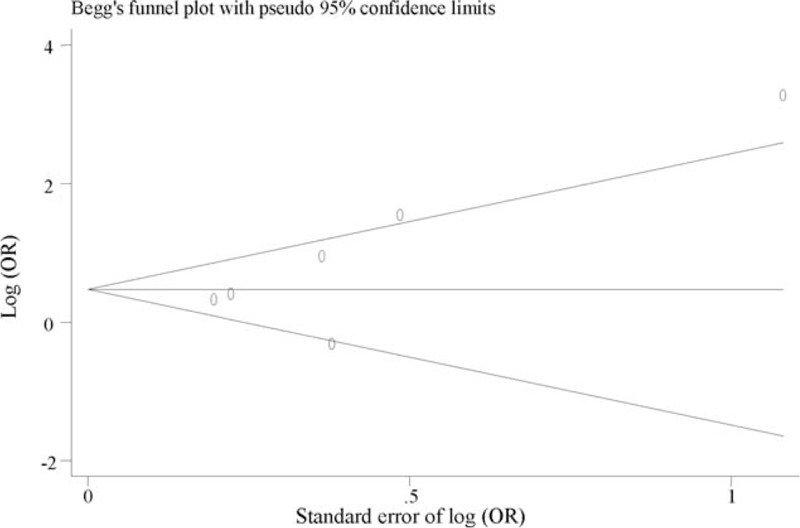

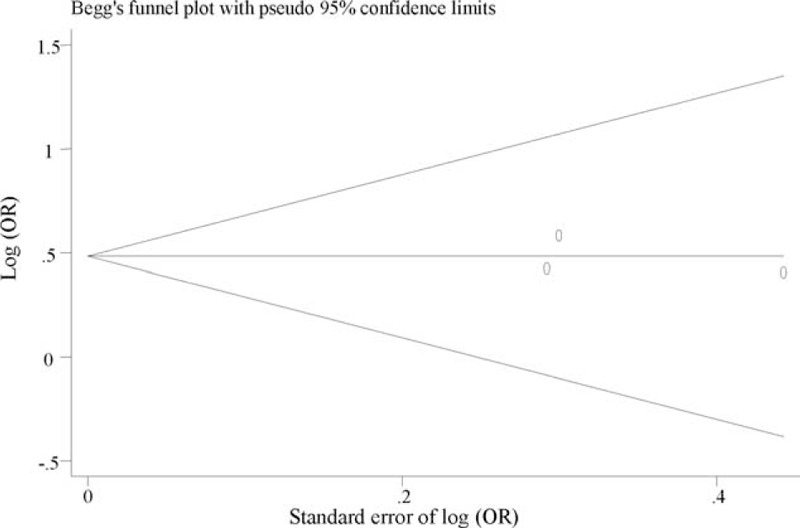

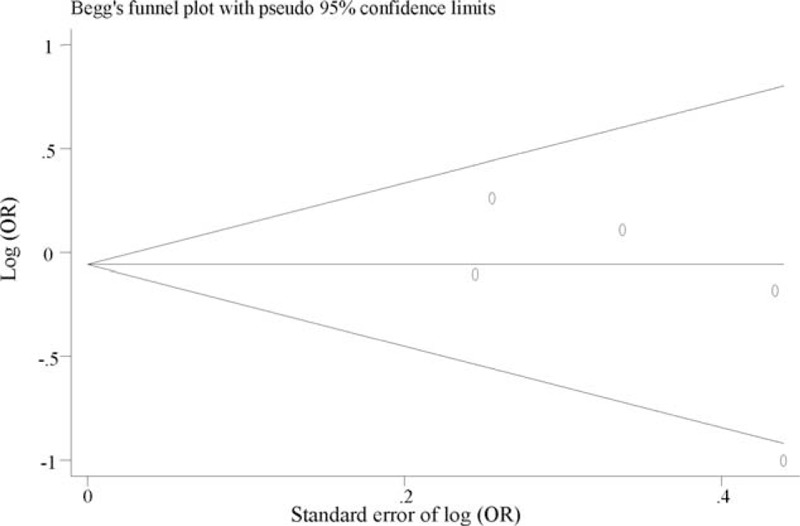

Assessment of Publication Bias

We found no evidence of publication bias for the meta-analysis of DRD2 (P = 0.143, Figure 2), SLC6A3 (P = 0.730, Figure 3), and COMT (P = 0.238, Figure 4). Assessment of publication bias for the meta-analysis of DBH is not meaningful due to limited number of studied included in the meta-analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Funnel plot for meta-analysis of the association of rs1800497 in DRD2 with PTSD. The x-axis is the standard error of the log-transformed OR (log [OR]), and the y-axis is the log-transformed OR. The horizontal line in the figure represents the overall estimated log-transformed OR. The 2 diagonal lines represent the pseudo 95% confidence limits of the effect estimate. OR = odds ratio, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

FIGURE 3.

Funnel plot for meta-analysis of the association of VNTR in SLC6A3 with PTSD. The x-axis is the standard error of the log-transformed OR (log [OR]), and the y-axis is the log-transformed OR. The horizontal line in the figure represents the overall estimated log-transformed OR. The 2 diagonal lines represent the pseudo 95% confidence limits of the effect estimate. OR = odds ratio, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder, SLC6A3 = solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 3, VNTR = variable number tandem repeat.

FIGURE 4.

Funnel plot for meta-analysis of the association of rs4680 in COMT with PTSD. The x-axis is the standard error of the log-transformed OR (log [OR]), and the y-axis is the log-transformed OR. The horizontal line in the figure represents the overall estimated log-transformed OR. The 2 diagonal lines represent the pseudo 95% confidence limits of the effect estimate. COMT = catechol-o-methyltransferase, OR = odds ratio, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

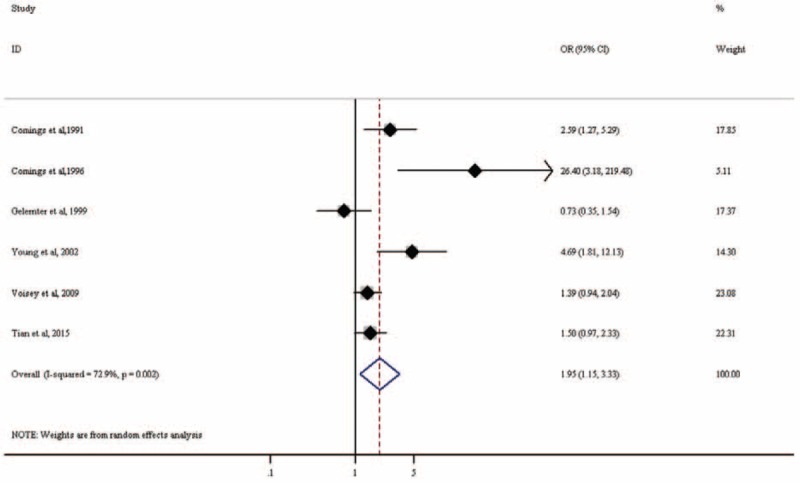

Association of rs1800497 in DRD2 with PTSD

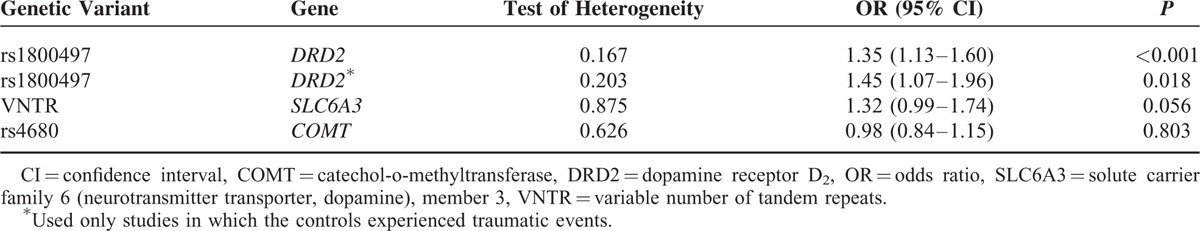

Six studies including a total of 597 PTSD patients and 1155 controls examined the association of rs1800497 with PTSD. With the exception of 1 study, all studies seemed to indicate that the A1 allele increased PTSD risk (eTable 1). Our meta-analysis found that rs1800497 is significantly associated with PTSD (OR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.15–3.33; P = 0.014; Figure 5). There was heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 72.9%, P = 0.002). Random-effects meta-analysis under GLM confirmed our finding (OR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.13–1.60, P < 0.001; Table 2).

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of the association of rs1800497 in DRD2 with PTSD. Each study is represented by a square whose area is proportional to the weight of the study. The overall effect from meta-analysis is represented by a diamond whose width represents the 95% CI for the estimated OR. CI = confidence interval, DRD2 = dopamine receptor D2, OR = odds ratio, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Basic Characteristics of all Studies

TABLE 2.

Meta-Analysis of Association of Genetic Variants in DRD2, SLC6A3, and COMT With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Using Metafor

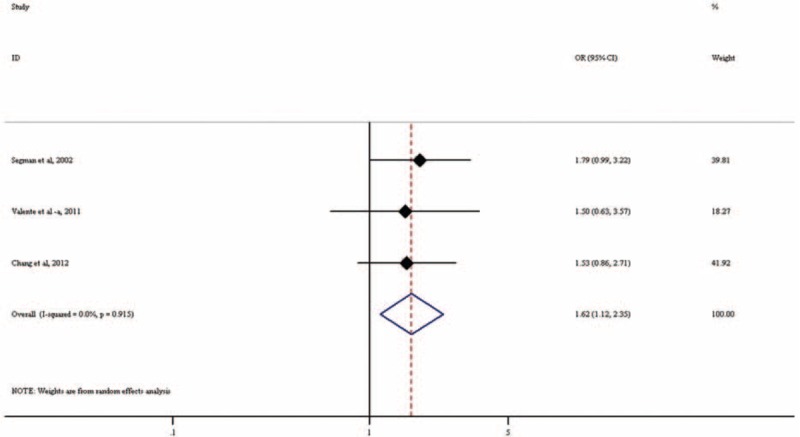

Association of VNTR in SLC6A3 With PTSD

Three studies including a total of 213 PTSD patients and 387 controls examined the association of 3′-UTR VNTR with PTSD. All studies seemed to indicate that the 9R increased PTSD risk (eTable 2). Our meta-analysis found that 9R is significantly associated with PTSD (OR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.12–2.35; P = 0.010; Figure 6). There was low heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.915). Association in the random-effects meta-analysis under GLM was attenuated but still indicated a trend for association (OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 0.99–1.74, P = 0.056; Table 2).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of the association of VNTR in SLC6A3 with PTSD. Each study is represented by a square whose area is proportional to the weight of the study. The overall effect from meta-analysis is represented by a diamond whose width represents the 95% CI for the estimated odds ratio (OR). OR = odds ratio, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder, SLC6A3 = solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 3, VNTR = variable number tandem repeat.

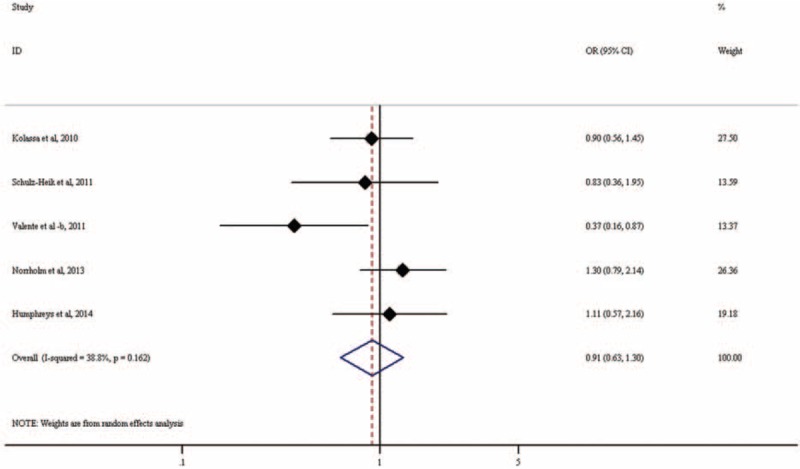

Association of rs4680 in COMT With PTSD

Five studies including a total of 626 PTSD patients and 418 controls examined the association of Val158Met (rs4680) with PTSD. Findings from these studies are inconsistent, with some34,35 indicating that Val/Val increased PTSD risk while others27,29,30 indicating decreased PTSD risk (eTable 3). Our meta-analysis found that rs4680 is not significantly associated with PTSD (OR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.63–1.30; P = 0.595; Figure 7). There was no heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 38.8%, P = 0.162). Random-effects meta-analysis under GLM confirmed our finding (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.84–1.15, P = 0.803; Table 2).

FIGURE 7.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of the association of rs4680 in COMT with PTSD. Each study is represented by a square whose area is proportional to the weight of the study. The overall effect from meta-analysis is represented by a diamond whose width represents the 95% CI for the estimated odds ratio (OR). COMT = catechol-o-methyltransferase, OR = odds ratio, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Association of rs161115 in DBH With PTSD

Only 2 studies including a total of 202 PTSD patients and 192 controls examined the association of rs1611115 with PTSD. Our meta-analysis did not find a significant association of homozygous TT with PTSD risk (OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 0.39–6.20; P = 0.536; eTable 4). However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to very limited sample size.

Sensitivity Analysis

We repeated the meta-analysis for rs1800497 in DRD2 after excluding studies in which the subjects in the control might not have experienced traumatic events.19,21,23,26 In such a case, we are testing the association with traumatic resilience. We did not find a significant association of rs1800497 with PTSD resilience (OR = 5.23, 95% CI: 0.30–90.03; P = 0.255; eTable 1), probably due to larger variance owing to reduced sample size. Random-effects meta-analysis under GLM still indicated significant association of rs1800497 with PTSD (OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.07–1.96; P = 0.018; Table 2). Our observed association of rs1800497 with PTSD remained when we limit our analysis to studies including only Caucasian subjects (OR = 3.16, 95% CI: 1.34–7.43; P = 0.008), or only subjects who had experienced combat traumatic events (OR = 2.28, 95% CI: 1.08–4.81; P = 0.032).

The association of rs1800497 with PTSD was attenuated when we included only studies that satisfied HWE in the control group (OR = 1.77, 95% CI: 0.93–3.39; P = 0.085). Again, this is probably due to limited power owing to reduced sample size. All the included studies for meta-analysis of the VNTR in SLC6A3 satisfied HWE in the control group. For meta-analysis of rs4680 in COMT, we observed similar nonsignificant association after excluding studies that violated HWE (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.75–1.43; P = 0.838).

All the included studies for meta-analysis of rs1800497 assessed current PTSD. When we limit our analysis to include only studies assessing current PTSD, our results remained unchanged for the meta-analysis of the VNTR in SLC6A3 (OR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.04–2.75; P = 0.034) and rs4680 in COMT (OR = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.53–1.47; P = 0.625).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we performed a systematic literature search and conducted meta-analyses to examine the association of genetic variants in the dopaminergic system with PTSD. We found that rs1800497 in DRD2 and the VNTR in SLC6A3 showed significant association with PTSD risk, but not rs4680 in COMT. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis on the association of genetic variants in the dopaminergic system with PSTD.

Previous studies have identified multiple SNPs in the dopaminergic system associated with PTSD;9 however, their functions in the pathogenesis of PTSD is largely unknown. Dopamine receptors, including D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5, belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor family that inhibits adenylyl cyclase. The DRD2 receptor is associated with pleasure and reward circuitry.38 Missense and other mutations in DRD2 are associated with movement disorder, myoclonus dystonia, and schizophrenia.39 The DRD2/ANKK1-Taq1A polymorphism (rs1800497) was previously assigned to DRD2, but later it was found to reside in exon 8 of ANKK1. This polymorphism is related to the regulation of dopamine synthesis and DRD2 receptor density in the brain.40 It has been linked with several neuropsychiatric disorders, such as ADHD and Tourette syndrome.41 Most included studies on the association of PTSD with genetic variants in DRD2 focus on rs1800497. One recent study found that several other polymorphisms in DRD2, such as rs12364283, exhibited strong associations with PTSD.26 This functional DRD2 promoter polymorphism rs12364283, located in a conserved repressor region of DRD2 promoter, is in low linkage disequilibrium with rs1800497 (r2 = 0.001). Another research found that rs12364283 was associated with enhanced DRD2 expression.42 Further analysis of the flanking conserved sequences of this SNP suggested that the minor C allele alters the binding sites of the putative transcription factor which upregulates DRD2 expression.42

COMT, located on chromosome 22q11.1-q11.2, is an important enzyme involved in the catalyses and inactivation of catecholamines. COMT has a functional polymorphism at codon 158 (rs4680). Substitution of valine (Val) by methionine (Met) is associated with reduced enzyme activity.43 This polymorphism has been found to be associated with multiple neuropsychiatric/psychological disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and diminished fear extinction which is a putative trait of PTSD.44 Of the 5 studies examining the association of rs4680 with PTSD, only 1 study indicated significant association.31 Subjects in this study all experienced urban violence, compared to other studies in which subjects experienced combat trauma or mixed types of trauma. Another study found no main effect of rs4680 on lifetime PTSD, but discovered a gene–environment interaction such that Met/Met homozygote carriers exhibited higher risk of PTSD, independently of traumatic load, while carriers of other genotypes show increased PTSD risk only in subjects with more severe traumatic load.27 However, the exact reasons accounting for the inconsistencies in the findings remain unclear.

Brain imaging technologies, including positron emission tomography (PET), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and functional MRI (fMRI), have experienced dramatic development to explore etiology of PTSD and to assess the effects of traumatic stress on the brain.45 Imaging studies found that hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex (including anterior cingulate) are implicated in PTSD and other psychiatric disorders.46,47 Although PTSD shares a lot of similar and overlapping symptoms with other psychiatric disorders and traumatic brain injury (TBI), recent brain imaging studies identified the link between PTSD symptoms and specific brain activity, and showed that imaging techniques can distinguish PTSD from TBI.48,49 Integrating genotyping of PTSD risk loci, once confirmed, with recently developed imaging techniques might help early detection and diagnosis of PTSD.

There are limitations with this study:

The sample size is limited for some studies. More studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate our findings.

The type and severity of traumatic events varied across studies. The high level of heterogeneity of trauma exposure might partly explain the nonsignificant association between rs4680 in COMT with PSTD. However, lack of data regarding trauma exposure at an individual level prevented us from examining the genetic association by trauma type.

Due to lack of data, we could not control for potential confounding factors, such as age at traumatic events and gender, and could not examine the gene–environment interaction.

In summary, in this study, we performed meta-analyses to analyze the association of PTSD with multiple genetic variants in the dopaminergic system. We found 1 genetic variant in DRD2 and 1 in SLC6A3 showing a significant association with PSTD susceptibility. More studies of larger sample sizes with more homogeneous traumatic exposure are needed to valid our findings and to explore additional PSTD risk loci.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the support from Special Foundation for Science and Technology Innovation of Shenyang-Special Program for Science and Technology Development of Population and Health (F13-220-9-53), Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2013021083 and 2015020460), the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry (NO. 2013-1792), and the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (15411951800). The authors also thank the support from A Joint Research Program for Management of Key Diseases by Shanghai Public Health System (2014ZYJB0007 to Xiaofeng Tao and DM); NIH/NIA grant R01AG036042 and the Illinois Department of Public Health (to JY).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, COMT = catechol-o-methyltransferase, DBH = dopamine beta-hydroxylase, DRD2 = dopamine receptor D2, GLM = generalized linear model, HWE = Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, OR = odds ratio, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder, SLC6A3 = solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 3, VNTR = variable number tandem repeat

This project was supported by Special Foundation for Science and Technology Innovation of Shenyang-Special Program for Science and Technology Development of Population and Health (F13-220-9-53), Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2013021083 and 2015020460), the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry (NO. 2013-1792), and the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (15411951800). Dr Ma's research was supported by a grant from A Joint Research Program for Management of Key Diseases by Shanghai Public Health System (2014ZYJB0007 to Xiaofeng Tao and DM). Dr Jingyun Yang's research was supported by NIH/NIA grant R01AG036042 and the Illinois Department of Public Health.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Broekman BF, Olff M, Boer F. The genetic background to PTSD. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2007; 31:348–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenen KC, Stellman SD, Sommer JF, Jr, et al. Persisting posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and their relationship to functioning in Vietnam veterans: a 14-year follow-up. J Trauma Stress 2008; 21:49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorge RE. Posttraumatic stress disorder. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015; 21:789–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen M, Roth A, Kyzar EJ, et al. Decoding the contribution of dopaminergic genes and pathways to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Neurochem Int 2014; 66:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girault JA, Greengard P. The neurobiology of dopamine signaling. Arch Neurol 2004; 61:641–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kienast T, Heinz A. Dopamine and the diseased brain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2006; 5:109–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faraone SV, Khan SA. Candidate gene studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67 Suppl 8:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamner MB, Diamond BI. Elevated plasma dopamine in posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 33:304–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornelis MC, Nugent NR, Amstadter AB, et al. Genetics of post-traumatic stress disorder: review and recommendations for genome-wide association studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2010; 12:313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charney DS. Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:195–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cubells JF, Zabetian CP. Human genetics of plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity: applications to research in psychiatry and neurology. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004; 174:463–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason JW, Giller EL, Kosten TR, et al. Elevation of urinary norepinephrine/cortisol ratio in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1988; 176:498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geracioti TD, Jr, Baker DG, Ekhator NN, et al. CSF norepinephrine concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1227–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almli LM, Fani N, Smith AK, et al. Genetic approaches to understanding post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014; 17:355–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stijnen T, Hamza TH, Ozdemir P. Random effects meta-analysis of event outcome in the framework of the generalized linear mixed model with applications in sparse data. Stat Med 2010; 29:3046–3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Stat Med 2004; 23:1351–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Berlin JA, et al. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of the performance of meta-analytical methods with rare events. Stat Med 2007; 26:53–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comings DE, Comings BG, Muhleman D, et al. The dopamine D2 receptor locus as a modifying gene in neuropsychiatric disorders. JAMA 1991; 266:1793–1800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comings DE, Muhleman D, Gysin R. Dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene and susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder: a study and replication. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelernter J, Southwick S, Goodson S, et al. No association between D2 dopamine receptor (DRD2) “A” system alleles, or DRD2 haplotypes, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segman RH, Cooper-Kazaz R, Macciardi F, et al. Association between the dopamine transporter gene and posttraumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2002; 7:903–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young RM, Lawford BR, Noble EP, et al. Harmful drinking in military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: association with the D2 dopamine receptor A1 allele. Alcohol Alcohol 2002; 37:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mustapic M, Pivac N, Kozaric-Kovacic D, et al. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) activity and -1021C/T polymorphism of DBH gene in combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2007; 144B:1087–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dragan WL, Oniszczenko W. The association between dopamine D4 receptor exon III polymorphism and intensity of PTSD symptoms among flood survivors. Anxiety Stress Coping 2009; 22:483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voisey J, Swagell CD, Hughes IP, et al. The DRD2 gene 957C > T polymorphism is associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in war veterans. Depress Anxiety 2009; 26:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolassa IT, Kolassa S, Ertl V, et al. The risk of posttraumatic stress disorder after trauma depends on traumatic load and the catechol-o-methyltransferase Val(158)Met polymorphism. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67:304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang YL, Li W, Mercer K, et al. Genotype-controlled analysis of serum dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity in civilian post-traumatic stress disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2010; 34:1396–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz-Heik RJ, Schaer M, Eliez S, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism moderates anterior cingulate volume in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2011; 70:1091–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valente NL, Vallada H, Cordeiro Q, et al. Candidate-gene approach in posttraumatic stress disorder after urban violence: association analysis of the genes encoding serotonin transporter, dopamine transporter, and BDNF. J Mol Neurosci 2011; 44:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valente NL, Vallada H, Cordeiro Q, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) val158met polymorphism as a risk factor for PTSD after urban violence. J Mol Neurosci 2011; 43:516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang SC, Koenen KC, Galea S, et al. Molecular variation at the SLC6A3 locus predicts lifetime risk of PTSD in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study. PLoS One 2012; 7:e39184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson EC, Heath AC, Lynskey MT, et al. PTSD risk associated with a functional DRD2 polymorphism in heroin-dependent cases and controls is limited to amphetamine-dependent individuals. Addict Biol 2014; 19:700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norrholm SD, Jovanovic T, Smith AK, et al. Differential genetic and epigenetic regulation of catechol-O-methyltransferase is associated with impaired fear inhibition in posttraumatic stress disorder. Front Behav Neurosci 2013; 7:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humphreys KL, Scheeringa MS, Drury SS. Race moderates the association of catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype and posttraumatic stress disorder in preschool children. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2014; 24:454–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf EJ, Mitchell KS, Logue MW, et al. The dopamine D3 receptor gene and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 2014; 27:379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian Y, Liu H, Guse L, et al. Association of genetic factors and gene-environment interactions with risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder in a case-control study. Biol Res Nurs 2015; 17:364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noble EP. The DRD2 gene in psychiatric and neurological disorders and its phenotypes. Pharmacogenomics 2000; 1:309–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klein C, Brin MF, Kramer P, et al. Association of a missense change in the D2 dopamine receptor with myoclonus dystonia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96:5173–5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neville MJ, Johnstone EC, Walton RT. Identification and characterization of ANKK1: a novel kinase gene closely linked to DRD2 on chromosome band 11q23.1. Hum Mutat 2004; 23:540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Comings DE, Wu S, Chiu C, et al. Polygenic inheritance of Tourette syndrome, stuttering, attention deficit hyperactivity, conduct, and oppositional defiant disorder: the additive and subtractive effect of the three dopaminergic genes–DRD2, D beta H, and DAT1. Am J Med Genet 1996; 67:264–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Bertolino A, Fazio L, et al. Polymorphisms in human dopamine D2 receptor gene affect gene expression, splicing, and neuronal activity during working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:20552–20557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lachman HM, Papolos DF, Saito T, et al. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase pharmacogenetics: description of a functional polymorphism and its potential application to neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacogenetics 1996; 6:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark R, DeYoung CG, Sponheim SR, et al. Predicting post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans: interaction of traumatic load with COMT gene variation. J Psychiatr Res 2013; 47:1849–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liberzon I, Phan KL. Brain-imaging studies of posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr 2003; 8:641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith ME. Bilateral hippocampal volume reduction in adults with post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of structural MRI studies. Hippocampus 2005; 15:798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rauch SL, Shin LM, Segal E, et al. Selectively reduced regional cortical volumes in post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuroreport 2003; 14:913–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amen DG, Raji CA, Willeumier K, et al. Functional neuroimaging distinguishes posttraumatic stress disorder from traumatic brain injury in focused and large community datasets. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0129659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pietrzak RH, Naganawa M, Huang Y, et al. Association of in vivo kappa-opioid receptor availability and the transdiagnostic dimensional expression of trauma-related psychopathology. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71:1262–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.