Abstract

Background & Aims

Constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 pathways in human colorectal cancers links inflammation to CRC development and progression. However, the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Here we investigated the roles of miR-221 and miR-222 in regulating both NF-κB and STAT3 activities and colorectal tumorigenesis.

Methods

miR-221/222 mimics and their inhibitors/sponges were transiently or stably transfected into cells. Dual luciferase reporter assays were utilized to examine the activation of both NF-κB and STAT3 signaling, as well as the regulation of miR-221/222. Quantitative PCR and immunoblot analysis were employed to examine the mRNA and protein expression. MTT assay, flow cytometric analysis and xenotransplant of tumor cells were performed to investigate the CRC cell growth in vitro and in vivo.

Results

miR-221 and miR-222 positively regulate both NF-κB and STAT3 activities, which in return induce miR-221/222 expression, creating a positive feedback loop in human CRCs. miR-221/222 directly bind to the coding region of RelA, leading to increased RelA mRNA stability. In addition, miR-221/222 reduce ubiquitination of RelA and STAT3 proteins by directly targeting the 3′ UTR of PDLIM2, an E3 ligase for both RelA and STAT3. We demonstrate that disruption of the positive feedback loop suppresses human CRC cell growth in vitro and in vivo. The expression of miR-221/222 correlates with the expression of RelA, STAT3 and PDLIM2 in human CRC clinical samples.

Conclusions

Our findings define a novel miR-221/222 mediated mechanism underlying constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 pathways in human CRCs and provide a promising therapeutic target for human CRCs.

Keywords: miR-221/222, NF-κB, STAT3, Colorectal cancers

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks the third in morbidity and fourth in mortality of all human cancers worldwide. In recent years it has been increasingly documented that inflammation promotes human CRC development and progression. NF-κB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathways are critical for inflammation and inflammation-associated colorectal tumorigenesis and metastasis 1-3. Recently, more and more evidence suggests that NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways are involved in tumor initiation and progression, indicating a direct link between inflammation and cancer progression, especially in inflammation-associated cancers where both pathways are frequently activated by proinflammatory factors or constitutively activated via mechanisms not well elucidated 3, 4.

NF-κB family consists of dimers of NF-κB1 (p50), NF-κB2 (p52), RelA, RelB, and c-Rel proteins, with RelA/p50 heterodimers being the predominant form generally representing classical NF-κB signaling pathway. In resting cells, RelA/p50 heterodimer is bound to IκBs and sequestered in the cytoplasm. In response to various stimuli like proinflammatory factors, IKKs are activated, resulting in phosphorylation, ubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation of IκBs. Thus, RelA/p50 heterodimer is liberated and translocates to the nucleus, where it transactivates downstream target genes 5, 6. STAT3 activation depends on its phosphorylation induced by upstream kinases such as JAK2. JAK2 is activated upon conjugation of the ubiquitously expressed gp130 receptor by its specific ligands, for example, IL-6 3.

NF-κB signaling is tightly regulated under normal circumstances. It has been well established that NF-κB signaling induces IκBα, resulting in export of nuclear NF-κB, a negative feedback mechanism for regulating NF-κB signaling 5. RelA phosphorylation and subsequent acetylation by p300/CBP influence RelA stability. Recently it was reported that ubiquitination and degradation of nuclear RelA is mediate by a nuclear ubiquitin E3 ligase PDLIM2 to terminate NF-κB activation 7. However, in tumor cells, various molecular alterations may result in a deregulated activation of NF-κB signaling 7. In cultured colon cancer cells with constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling IKK is not often activated, suggesting existence of IKK-independent mechanisms 8. For example, reduced expression of PDLIM2 in colorectal tumor cells has been observed which contributes to constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling 9. STAT3, a critical downstream transcription factor of IL-6 signaling, has recently been shown to play a critical role in maintaining constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling; STAT3 may prolong the nuclear retention of RelA through acetyltransferase p300-mediated RelA acetylation 8. Thus, activated STAT3 may partially account for constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling in human cancers. Constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling depends on cytokine production by tumor cells in an autocrine manner, particularly, inflammatory cytokines and growth factors 10, 11. However, other mechanisms to maintain constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling in cancer cells still remain to be elucidated.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous, short (∼23 nt) RNAs that suppress gene expression via sequence-specific interactions with the 3′ untranslated regions of related mRNA targets 12. miRNAs are known to regulate a variety of genes involved in the control of development, proliferation and apoptosis. Altered expression of miRNAs may contribute to cancer initiation and progression. Many miRNAs have been found to have different expressions in colorectal cancer tissues and normal tissues 13, 14.

Here we report that miR-221 and miR-222 levels are elevated in human CRCs. miR-221/222 stabilize rela mRNA by directly binding to its coding region and also upregulate RelA and STAT3 proteins by binding to the 3′UTR of PDLIM2 (PDZ and LIM domain 2). In addition, miR-221/222 are induced by RelA and STAT3 in human CRCs, thus forming a positive feedback which contributes to constitutive activation NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways. Disruption of this positive feedback loop using RelA knockdown or miR-221 and 222 inhibitors suppresses CRC cell growth in vitro and in vivo, suggesting crucial roles of this novel regulatory mechanism in human CRCs.

Materials and Methods

Extensive details for all experimental procedures are provided in the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Mice

Male BALB/c and BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai. All animals were housed and maintained in pathogen-free conditions. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the institutional biomedical research ethics committee of the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Cell Culture

Human colon cancer cell line HCT116, RKO, Lovo, DLD-1, HCT15, HT29, H508, SW1116, and SW480 were purchased from ATCC. Cells were cultured in DMEM medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% FES and 10 units/ml penicillin.

Real-Time PCR Analysis

RNA purified from HCT116, RKO, Lovo, DLD-1, HCT15, HT29, H508, SW1116, and SW480 cells under different transfection conditions with siRNAs or miRNAs was reverse transcribed to form cDNA, which was subjected to SYBR Green-based real-time PCR analysis. Primer sequences can be found in the Supplementary Table 1.

Human Colorectal Cancer Tissues

Colon carcinoma tissues were selected from tissue bank of the Institute. The local ethics committee approved the study and the regulations of the same committee of the Institute were obeyed; written consent has been obtained.

Results

miR-221/222 positively regulate NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways

It has been reported that increased expression of RelA/NF-κB protein correlates with colorectal tumorigenesis 2, 10, 15-18. We found that the mRNA and protein levels of RelA and RelB were significantly higher in human CRC tissues/cell lines than in normal colon tissues/cell lines (Figure S1 and unpublished data). miRNAs have recently been shown to regulate NF-κB signaling 19. Several miRNAs were reported to be aberrantly expressed in colorectal cancers 20. We hypothesized that deregulated miRNA expression might contribute to constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling in human CRCs. In order to test our hypothesis, we ectopically introduced mimics or inhibitors for these differentially expressed miRNAs into RKO cells and then examined their effect on NF-κB activity. Among these miRNAs, miR-221 and miR-222 were found to positively regulate NF-κB activity (Figure 1A). We performed the same experiment in HCT116 cells, and found that miR-221/222 increased NF-κB activity (Figure 1B). In addition, the inhibitors of miR-221/222 suppressed basal and IL-1β- or TNFα-induced NF-κB activity in these cell lines (Figure 1B). Taken together, miR-221/222 positively regulate NF-κB signaling.

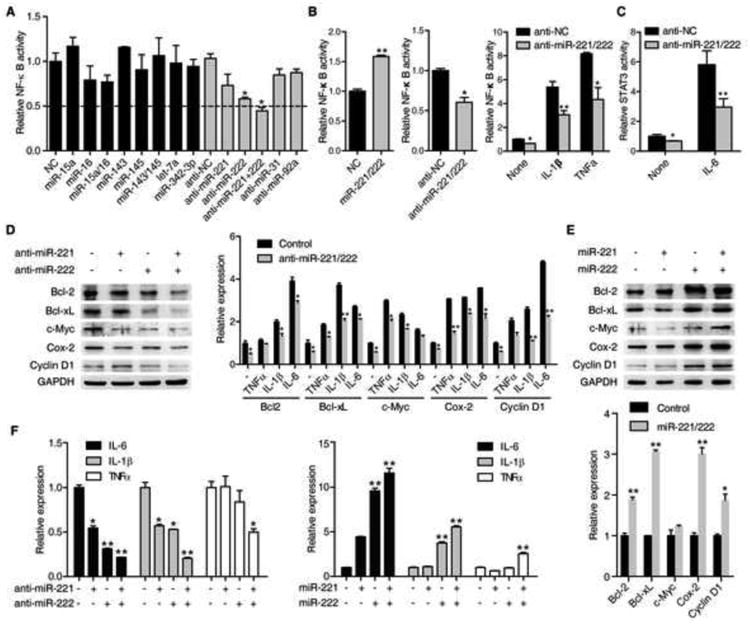

Figure 1. miR-221/222 regulate NF-κB and STAT3 transactivities.

(A) NF-κB luciferase activity (mean ± SD) in RKO cells treated with different miRNA mimics (100 nM) or antisense (100 nM) for 48 hr.

(B) NF-κB luciferase activity (mean ± SD) in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM negative control (NC) or miR-221/222 mimics (left) or antisense (middle) for 48 hr. NF-κB luciferase activity (mean ± SD) in RKO cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr, then treated with or without IL-1β or TNFα for 6 hr (right).

(C) STAT3 luciferase activity (mean ± SD) in RKO cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr, then treated with or without IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for 6 hr.

(D) The protein levels of target genes of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 antisense (left). The mRNA levels (mean ± SD) of target genes of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-221/222 antisense for 72 hr then treated with or without TNFα (10 ng/ml), IL-1β (20 ng/ml), and IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for 6 hr (right).

(E) The protein (upper panel) and mRNA (bottom panel) (mean ± SD) levels of target genes of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways in HCT116 cells treated with miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 mimics.

(F) mRNA levels (mean ± SD) of IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 antisense (left) or mimics (right) for 72 hr.

Intriguingly, we found that miR-221/222 also regulated the transactivity of STAT3, another critical transcription factor in human CRCs. Introduction of inhibitors of both miRNAs suppressed basal or IL-6-activated STAT3 activity (Figure 1C). To confirm the above findings, we determined the basal and cytokine-induced expression of downstream target genes of the two pathways. Consistently, miR-221 and miR-222 inhibitors, or mimics did affect expression of the downstream target genes of both pathways (Figure 1D and E). Of note, among the targets, IL-6, IL-1β and/or TNFα produced by tumor cells were regulated by miR-221 and/or miR-222 (Figure 1F). Additionally, our results also showed that both miRNAs exhibited synergistic effects, to some extent, in regulating the activities of NF-κB and STAT3.

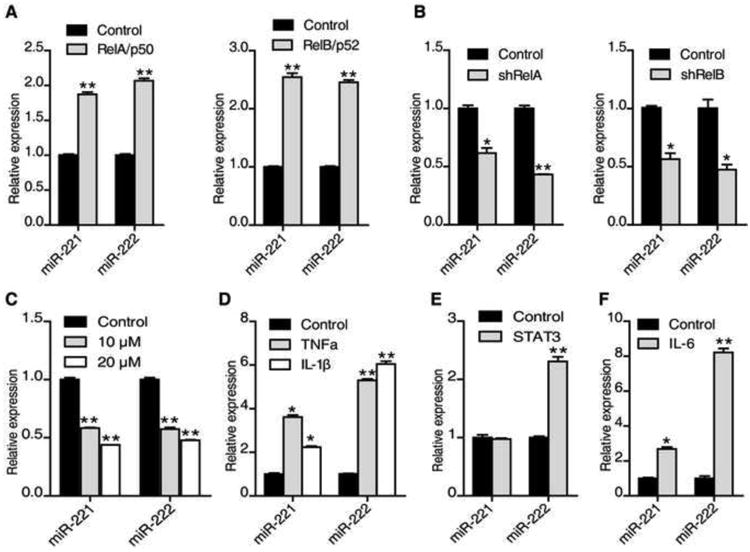

Activation of both NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways induces miR-221/222

We examined whether the expression of both miR-221 and miR-222 is regulated by NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways. First, we observed that overexpression of RelA/p50 and RelB/p52 markedly upregulated the expression of miR-221/222 in HCT116 cells (Figure 2A). Second, depletion of RelA or RelB using specific shRNAs to block NF-κB pathway decreased miR-221/222 expression (Figure 2B). miR-221/222 expression was also repressed by the NF-κB inhibitor Bay-117082 (Figure 2C). Third, stimulation with IL-1β or TNFα dramatically induced miR-221/222 expression (Figure 2D). Similarly, STAT3 overexpression or IL-6 stimulation also profoundly induced miR-221/222 expression in HCT116 cells (Figure 2E and F). Consistent with previous reports 14, the two miRNAs were highly expressed in human cancer colorectal tissues versus their normal counterparts (Figure S10 and 7A). These results collectively demonstrate that miR-221/222 positively regulate both NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways, which in return induce the expression of both miRNAs, creating a miR-221/222-mediated positive feedback loop.

Figure 2. Both NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways regulate miR-221/222 expression.

(A) miR-221 and miR-222 expression levels (mean ± SD) in HCT116 cells transfected with or without RelA/p50 or RelB/p52 plasmids for 48 hr.

(B) miR-221 and miR-222 expression levels (mean ± SD) in HCT116 cells transfected with or without shRelA or shRelB for 48 hr.

(C) miR-221 and miR-222 expression levels (mean ± SD) in HCT116 cells treated with 10μM, 20 μM BAY 11-7082 for 24 hr.

(D) miR-221 and miR-222 expression levels (mean ± SD) in HCT116 cells treated with or without TNFα (10 ng/ml) or IL-1β (20 ng/ml) for 24 hr.

(E and F) miR-221 and miR-222 expression levels (mean ± SD) in HCT116 cells transfected with or without STAT3 plasmid for 48 hr (E) or treated with IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for 6 hr (F). The data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

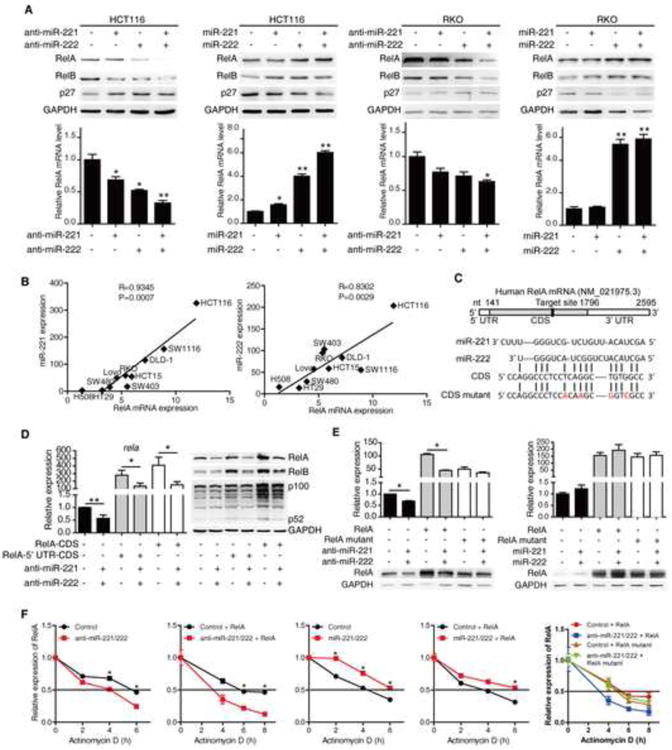

miR-221/222 stabilize RelA mRNA by binding to its coding region

To investigate how miR-221/222 positively regulate NF-κB activity, we introduced mimics or inhibitors of miR-221 or/and miR-222 in colon cancer cell lines and examined the expression of mRNAs and proteins associated with NF-κB signaling. Surprisingly, introduction of inhibitors of miR-221 or miR-222, or both markedly decreased RelA and RelB expression at mRNA and protein levels (Figure 3A). In contrast, elevated mRNA and protein levels of RelA and RelB were observed in HCT116 and RKO cells introduced with both miRNA mimics (Figure 3A). As expected, p27, the known target gene of miR-221/222 was increased. In addition, high correlation was observed between miR-221/222 and RelA mRNA in multiple human colorectal cancer cell lines (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. miR-221/222 regulate NF-κB signaling by upregulating RelA.

(A) The protein (upper panels) and mRNA (bottom panels) levels of RelA, RelB, and p27 in HCT116 cells and RKO cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 antisense or mimics for 72 hr.

(B) miR-221(left), miR-222 (right) and RelA levels in the indicated cell lines and correlation coefficients (R) were shown.

(C) The predicted binding sites of miR-221/222 in RelA coding region.

(D) mRNA (left) and protein (right) levels of RelA in HCT116 cells transfected RelA CDS with or without its 5′ UTR in the presence or absence of miR-221/222 antisense.

(E) mRNA (upper panels) and protein (bottom panels) levels of RelA in HCT116 cells (left) and 293T cells (right) transfected with wild-type RelA or RelA CDS mutant as well as 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense (left) or mimics (right) for 48 hr.

(F) RelA mRNA levels in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221/222 antisense or mimics for 48 hr then treated with actinomycin D (10 μg/ml) for indicated time. mRNA levels RelA in HCT116 cells transfected with wild-type RelA or RelA CDS mutant as well as with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr then treated actinomycin D (10 μg/ml) for indicated time (right).

In order to determine whether miR-221/222 regualte NF-κB signaling by RelA or RelB, we showed that both mRNA and protein of RelB were positively regulated by RelA in HCT116 cells and Lovo cells (Figure S2). RelA overexpression restored the level of RelB reduced by introduction of miR-221/222 inhibitors (Figure 3D and S3). Therefore, we hypothesized that miR-221/222 might directly regulate RelA expression, which in turn affects expression of RelB. To test our hypothesis, we first searched RelA mRNA sequence for putative binding sites of both miRNAs using computational tools (RNA22, http:/cbcsrv.watson.ibm.com/rna22.html). One predicted binding site of miR-221/222 was found only within the coding region of rela mRNA (Figure 3C). miRNAs have previously been reported to positively regulate gene expression by directly binding to the 5′ UTR or the promoter or coding region, in addition to the 3′UTR of target genes 21-23. The luciferase reporter assay showed that only the RelA coding region but not the 5′UTR was required for modulation by inhibitors or mimics of miR-221/222 on rela luciferase expression (Figure S4A and B). We then transfected plasmids expressing RelA cDNAs with or without its 5′UTR into HCT116 cells in the presence or absence of miR-221/222, and examined mRNA and protein expression of RelA. As expected, inhibitors of miR-221/222 dramatically inhibited mRNA and protein expression of RelA without 5′UTR (Figure 3D). In addition, the dependence of miR-221/222 regulation of mRNA and protein expression on the coding region is restricted to RelA but not RelB or IKKβ, both of which are highly homologous to RelA but do not contain the predicted binding sequence of miR-221/222 (Figure S5).

To confirm direct binding of miR-221/222 to the coding region of rela mRNA, we constructed plasmid of RelA with silent mutations in the predicted binding site that changed four nucleic acids but did not result in amino acid changes (Figure 3C). Mutations of the putative binding sequence attenuate the effects of the inhibitors or mimics of miR-221/222 on RelA mRNA and protein as compared to wild type (Figure 3E).

To test whether RelA CDS directly regulate gene transcription as an enhancer, we cloned an 800bp fragment of RelA containing the putative binding site of miR-221/222 into upstream of the promoter in the enhancer luciferase report construct. Partial RelA CDS containing miR-221/222 binding site did not affect gene transcription with or without inhibitors of miR-221/222 (Figure S4C). We therefore determined whether miR-221/222 might regulate RelA by affecting its mRNA stability. Indeed, the mRNA stability of endogenous or exogenous wild-type RelA was changed with introduction of inhibitors or mimics of both miR-221 and miR-222. Conversely, the mRNA stability of mutated RelA was not affected (Figure 3F). Collectively these results indicate that miR-221/222 upregulate rela mRNA levels by binding to its coding region and increasing its stability.

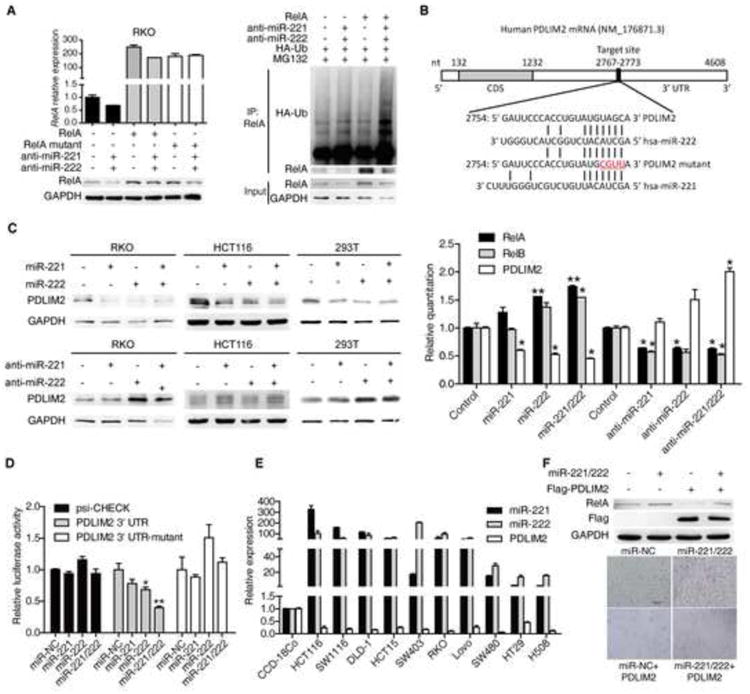

miR-221/222 regulate RelA protein ubiquitination by regulating PDLIM2

Our above data showed that miR-221/222 upregulated RelA protein expression by increasing rela mRNA stability in HCT116 cells. Interestingly, we also found that mutant RelA protein was still decreased by introducing the inhibitors of miR-221/222, whereas mRNA level basically remained unchanged in RKO cells (Figure 4A). Introduction of miR-221/222 inhibitors profoundly increased RelA polyubiquitination (Figure 4A), indicating that ubiquitination-dependent degradation of RelA was involved in miR-221/222 regulation of RelA protein expression.

Figure 4. miR-221/222 regulate RelA protein by regulating PDLIM2.

(A) mRNA (upper panel) and protein (bottom panel) levels of RelA in RKO cells separatively transfected with wild type or mutated RelA CDS as well as 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr (left). RelA ubiquitination level in RKO cells co-transfected with HA-Ub and 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense as well as RelA plasmid for 72 hr then 6 hr posttreatment with 5 μM MG132 (right).

(B) The predicted binding sites of miR-221/222 in PDLIM2 3′ UTR.

(C) PDLIM2 protein levels in RKO, HCT116 and 293T cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 mimics (upper panels) or antisense (bottom panels) for 48 hr (left). mRNA levels of RelA, RelB and PDLIM2 in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 mimics or antisense for 48 hr (right).

(D) The luciferase activity of PDLIM2 3′ UTR reporter in 293T cells transfected with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 mimics as well as 200 ng psiCHECK-PDLIM2 3′ UTR reporter plasmid, its mutant reporter plasmid and control plasmid for 48 hr.

(E) miR-221, miR-222, and PDLIM2 mRNA levels in different CRC cell lines. Normal colon fibroblast cell line CCD-18Co was used as control.

(F) RelA and PDLIM2 (Flag) protein levels (upper panel) and cell number (bottom panel) in RKO cells transfected with miR-NC or miR-221/222 mimics together with or without Flag-PDLIM2 plasmid for 48 hr.

Previous studies have demonstrated that SOCS1 and PDLIM2 are the E3 ligase for polyubiquitination and degradation of RelA protein to avoid over-activation of NF-κB under cytokine stimulation 7, 24. Analysis with bioinformatic prediction tool Miranda 25 shows that the 3′-UTR of SOCS1 and PDLIM2 contains a putative target site for miR-221/222 binding (Figure 4B). We found that introduction of inhibitors or mimics for miR-221/222 markedly affected the mRNA and protein expression of PDLIM2 but not SOCS1 (Figure 4C, data not shown). We then performed luciferase report assay of 3′UTR of pdlim2 gene to see if pdlim2 is directly regulated by miR-221/222. Indeed reduced luciferase activity was observed when a reporter construct of 3′UTR region of the PDLIM2 gene containing the predicted binding site of miR-221/222 was transfected with miR-221/222 mimics. And introduction of four point mutations in target sites was sufficient to diminish this effect (Figure 4D). In agreement, pdlim2 mRNA levels were significantly decreased while miR-221/222 levels were elevated in colon cancer cell lines, compared with those in CCD-18Co, a normal colon fibroblast cell line (Figure 4E).

Overexpression of PDLIM2 in RKO cells dramatically decreased RelA protein but not its mRNA, leading to reduced expression of its target genes (Figure S6A and B). To further examine if PDLIM2 is involved in miR-221/222 regulation of RelA protein, we overexpressed PDLIM2 in RKO cells and treated with miR-221/222 mimics. As shown in Figure 4F, PDLIM2 mitigated the effect of miR-221/222 mimics on RelA protein expression. In addition, expression of PDLIM2 was restored by introduction of miR-221/222 inhibitors rather than methylation inhibitor (Figure S7).

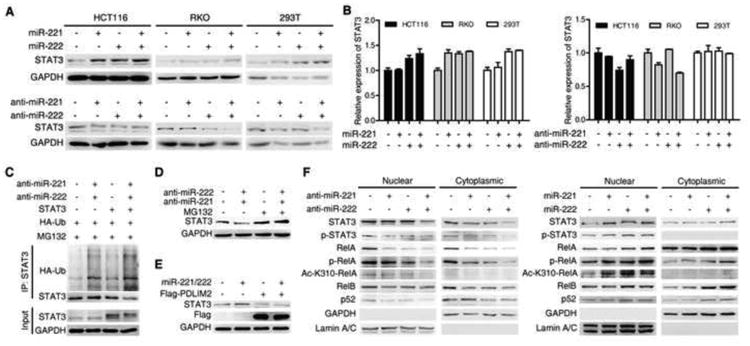

miR-221/222 regulate STAT3 and RelA acetylation by regulating PDLIM2-STAT3 regulatory axis

To investigate how miR-221/222 regulate STAT3 activity, we examined STAT3 protein and mRNA expression under the influence of miR-221/222. We found that miR-221/222 affected STAT3 protein but not mRNA (Figure 5A and B). Inhibitors of both miRNAs indeed resulted in increased ubiquitination of STAT3 (Figure 5C). In addition, MG132 treatment fully restored STAT3 protein levels reduced by inhibitors of miR-221/222 (Figure 5D), suggesting that miR-221/222 regulated STAT3 protein through ubiquitination-dependent mechanism. PDLIM2 has recently been shown to physically interact with STAT3 and mediate the ubiquitination and degradation of STAT3 in T cells 26. Given that PDLIM2 is a target of miR-221/222, it is plausible that PDLIM2 may be involved in miR-221/222 regulation of STAT3 protein. As shown in Figure S6A, overexpression of PDLIM2 also decreased STAT3 protein in RKO cells. Moreover, overexpression of PDLIM2 also fully diminished the induction of STAT3 protein by miR-221/222 mimics (Figure 5E). These data indicate that miR-221/222 regulate STAT3 protein via directly targeting PDLIM2. Additionally, STAT3 has been reported to increase RelA protein retention in the nucleus by promoting phosphorylation and acetylation of RelA. Clearly introduction of miR-221/222 inhibitors decreased STAT3 protein, and decreased level of RelA in cytoplasm as well as phosphorylated/acetylated and total nuclear RelA (Figure 5F). Conversely, overexpression of miR221/222 dramatically increased STAT3 protein, correspondently, not only leading to increased amount of RelA in cytoplasm, but also phosphorylated/ acetylated and total nuclear RelA (Figure 5F). We observed higher STAT3 protein expression in most human CRC cell lines compared to normal human colon fibroblast cell lines (Figure S8). Together, these data indicate that miR-221/222 suppress the polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of RelA and STAT3 by targeting PDLIM2, and increase phosphorylation and acetylation of RelA via PDLIM2-STAT3 axis, leading to constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 pathways.

Figure 5. miR-221/222 regulate STAT3 signaling by regulating PDLIM2.

(A and B) STAT3 protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels in HCT116, RKO and 293T cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 mimics or antisense for 48 hr.

(C) STAT3 ubiquitination in RKO cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisenses and HA-Ub plasmid with or withou STAT3 plasmid for 72 hr, then 6 hr posttreatment with MG132 (5 μM).

(D) STAT3 protein levels in RKO cells transfected with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr then treated with or without MG132 (5 μM) for 6 hr.

(E) STAT3 and PDLIM2 (Flag) protein levels in RKO cells treated with 100 Nm miR-NC or miR-221/222 mimics together with or without PDLIM2 plasmid for 48 hr.

(F) Nuclear or cytoplasmic protein levels of RelA, STAT3 and non-canonical NF-κB pathway related genes in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 antisense for 72 hr (left). Nuclear or cytoplasmic protein levels of RelA, STAT3 and non-canonical NF-κB pathway related genes in RKO cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 mimics for 72 hr (right).

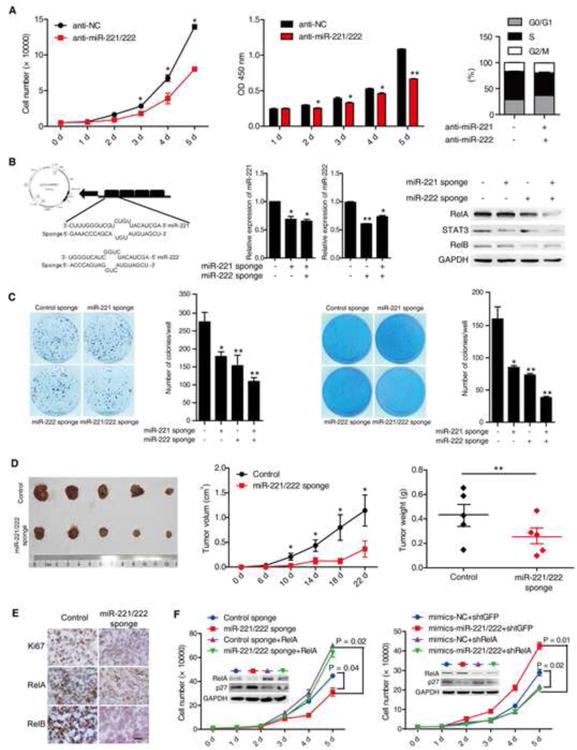

miR-221/222 mediated positive feedback loop is critical for cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo

NF-κB and STAT3 signaling are essential for cell growth and prevention from apoptosis 18, 27. To address whether the miR-221/222-mediated positive feedback loop plays a critical role in human CRC cell growth in vitro and in vivo, we blocked the feedback loop using sponge method to inhibit miR-221/222 or using RelA specific shRNAs to knock down RelA. HCT116 cell growth in vitro was significantly inhibited, marked by reduced cell number and cell viability, cell cycle arrest at the G1/S phase transition and decreased colony formation (Figure 6A and C, and S9A-S9E). To determine whether miR-221/222 regulates tumor growth in vivo, we used a miRNA sponge technique 28 to construct miR-221/222 sponge vector to inhibit their expression stably (Figure 6B). miR-221/222, RelA, RelB and STAT3 were decreased in these cells (Figure 6B). Block of the positive feedback loop with the sponge technique led to reduced tumor volume and weight, as well as fewer Ki67 positive cells in tumors (Figure 6D and E). The reduced expressions of RelA, RelB, NIK, p100, c-Myc, SKP2 and miR-221/222, as well as elevated expression of p27 were observed in tumor cells (Figure S9I-S9L). Taken together, our results indicate that the block of the miRNA-NF-κB positive feedback inhibits human CRC cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Although overexpression of miR-221/222 resulted in dramatic reduction in direct targets of miR-221/222 including p27, RelA knockdown completely reversed the phenotype of cell growth promotion by overexpression of miR-221/222 (Figure 6F). On the other hand, in the sponged HCT116 cell line, reduced miR-221/222 induced p27, but overexpression of RelA is still capable of driving cell growth (Figure 6F). These data indicate that the miR-221/222-NF-κB positive feedback loop mediating constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling plays a dominant role in promoting tumor cell growth.

Figure 6. miR-221/222 inhibitors suppress colon cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo.

(A) The growh curve of HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense in indicated days (left). The MTT results of HCT116 cells with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense in indicated days (middle). Anti-miR-221/222 blocked HCT116 cells in S phage (right).

(B) The diagrammatic sketch of miR-221/222 sponge construct (left). The expression of miR-221, miR-222 in HCT116 cells stably expressing scramble or miR-221/222 sponge (middle). RelA, STAT3, and RelB protein levels in HCT116 cells stably expressing scramble or miR-221/222 sponge (right).

(C) Colony formation assay of HCT116 cells stably expressing scramble or miR-221/222 sponge. Colony numbers were counted after 10 days (left). Soft agar colony formation assay of HCT116 cells stably expressing scramble or miR-221/222 sponge. Colony numbers were counted after 28 days (right).

(D) Tumor growth in mice injected with HCT116 cells stably expressing scramble or miR-221/222 sponge (left). Tumor volume (middle) and weight (right) in mice injected with HCT116 cells stably expressing scramble or miR-221/222 sponge (n = 5).

(E) The immunohistochemistry results of Ki67, RelA and RelB in tumors with HCT116 cells stably expressing scramble or miR-221/222 sponge.

(F) The growth curve of HCT116 cells stably expressing with control or miR-221/222 sponge with or without RelA overexpression (left). The growth curve of HCT 116 cells transfected with miR-NC or miR-221/222 mimics with or without RelA knockdown (right).

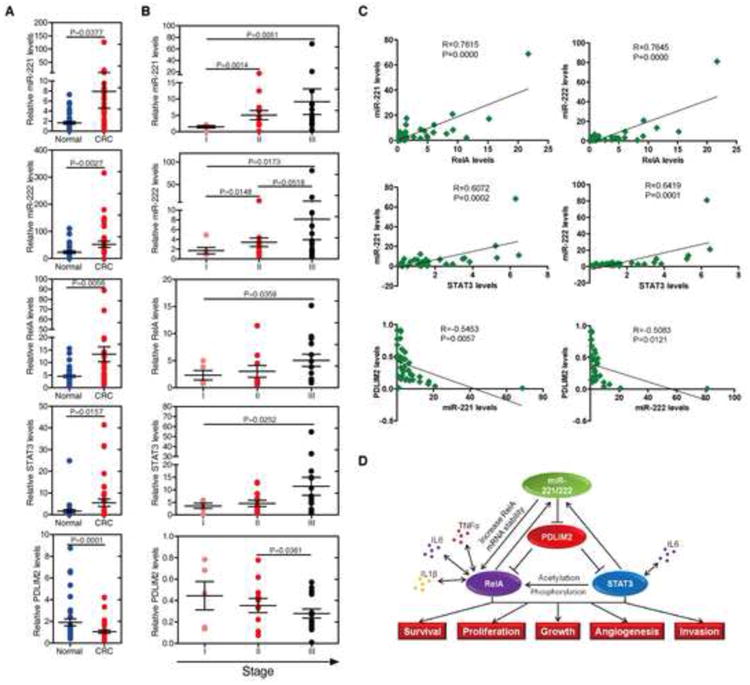

miR-221/222 are positively correlated with RelA and STAT3, but negatively correlated with PDLIM2 in human CRCs

To address the relevance of miR-221/222-mediated positive feedback loop to human CRCs we examined the expression of miR-221, miR-222, RelA, STAT3 and PDLIM2 in 37 paired human normal and cancer colorectal tissues. We found that the mRNA levels of miR-221, miR-222, RelA and STAT3 were higher, whereas that of PDLIM2 is much lower in cancer tissues than in their normal counterparts (Figure 7A and S10).

Figure 7. The relevance of miR-221/222-NF-κB-STAT3 circuit in human colon cancer development and progression.

(A) Assessment of miR-221, miR-222, RelA, STAT3, and PDLIM2 levels (mean ± SD) by real-time PCR analysis in total RNAs derived from 37 paired normal colon tissues and colorectal carcinomas.

(B) Assessment of miR-221/222, RelA, STAT3, and PDLIM2 levels in total RNAs derived from 37 colorectal carcinomas, according to their tumor stage. The experiments have been performed in triplicate, and data are shown as mean ± SD.

(C) Correlation between the expression levels of miR-221/222, RelA, STAT3, and PDLIM2 in above clinical samples. For the correlation between STAT3 and miR-221 or miR-222, STAT3 protein levels of 32 colorectarl carcinomas was used for analysis. Each data point represents an individual colon tissue sample, and a correlation coefficient (R) is shown.

(D) Schematic representation of the proposed miR-221/222-NF-κB-STAT3 feedback circuit in human CRC development and progression.

Furthermore, we were interested in identifying whether miR-221/222-NF-κB-STAT3 positive feedback loop plays a role during colon cancer progression. We found that miR-221, miR-222, RelA, and STAT3 levels increase progressively with progression of tumors, whereas PDLIM2 levels keep decreasing during CRC progression (Figure 7B and S10). In addition, a positive correlation between RelA or STAT3 and miR-221 or miR-222 levels, and an inverse relationship between PDLIM2 and miR-221 or miR-222 levels were observed (Figure 7C and S10). Together, these data strongly suggest that the, miR-221/222- NF-κB-STAT3 positive feedback loop is relevant to and important for the progression of human CRCs.

Discussion

Constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling has been reported to contribute to abnormal cell proliferation and inhibition of apoptotic cell death in cancers including acute T-lymphocyte leukemia, diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Hodgkin lymphoma, breast cancer, prostate cancer and others 29. Identification of master regulators for both signaling pathways will lead to further understanding of molecular pathology of tumorigenesis. We show that the miR-221/222-mediated positive feedback loop is critical for maintaining constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 pathways in human CRCs. miR-221/222 regulate NF-κB and STAT3 signaling by direct binding to rela coding region and stabilizing rela mRNA. Besides, miR-221/ 222 upregulate both RelA and STAT3 protein through binding to the 3′UTR of PDLIM2, an E3 ligase for both RelA and STAT3.

miR-221/222 have been shown to regulate cancer cell proliferation by targeting p27Kip1, RECK, c-Kit, TIMP3 and PTEN 30-34. Reciprocal rescuing experiments (Figure 6F) emphasized the importance of miR221/222 regulation on RelA expression in CRC cell growth, although downregulation of other targets by miR-221/ 222 also contributes to CRC cell growth. Nevertheless, the critical role of miR-221/222 in cancer cell growth renders it a promising therapeutic target in human CRCs.

miRNAs have been shown to regulate multiple signaling pathways. For example, miR-199a regulates IKKβ in tumour inflammatory microenvironment 35. miR-301a down-regulates NF-κB repressing factor gene expression 36. Polycomb-mediated loss of miR-31 activates NIK-dependent NF-κB pathway in adult T cell leukemia and other cancers 19. In addition, microRNAs might mediate inflammatory signaling circuit composed of miR-200c, p65, JNK2, HSF1 and IL-6, triggering the transformation of epithelial cells and mammary cell tumorigenesis37. Here we identify a miR-221/222- mediated positive feedback loop which functions to maintain constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling in human CRCs. Indeed, the miR-221/222-mediated loop may exist in other cancers, particularly in inflammation-associated cancers.

We provide several lines of evidence that miR-221/222 regulate RelA and STAT3 expression. Firstly, miR-221/222 directly bind to rela coding region and stabilize rela mRNA. Secondly, after being activated, RelA and STAT3 translocate into the nucleus where both proteins are polyubiquitinated by PDLIM2 38. miR-221/222 directly bind to 3′UTR of PDLIM2 and downregulate its mRNA and protein expression, and hence reduce the ubiquitination and degradation of RelA and STAT3 proteins. Thirdly, elevated STAT3 increases acetylation and nuclear retention of RelA protein. The duo mode of regulation of RelA by miR-221/222 is differentially adopted in different colorectal cell lines. For instance, in HCT116 cells, miR-221/222 regulate RelA mainly by affecting its mRNA stability through binding to its coding region (Figure 3), while in RKO cells, miR-221/222 regulate RelA through both mechanisms (Figure 4). PDLIM2 expression may be regulated by multiple mechanisms in human colorectal cell lines with various phenotypes. A recently study showed that suppression of PDLIM2 is DNA methylation-dependent 39. In our study, however, expression of PDLIM2 was restored by introduction of miR-221/222 inhibitors rather than methylation inhibitor (Figure S7), indicating a novel mechanism of PDLIM2 regulation by miR-221/222 in human CRCs.

In addition to downregulation of mRNA translation through binding to the mRNA 3′UTR, miRNAs have been shown to enhance mRNA translation by binding to the 5′UTR or complementary promoter sequences of target genes 22, 39, 40. miRNAs binding to the coding regions to reduce mRNA translation have been reported previously 41, 42. But we demonstrated that miR-221/222 increase rela mRNA stability by interacting with RelA coding region rather than the 5′ UTR or 3′ UTR. Enhancer reporter assay indicated that miR-221/222 were unlikely to enhance gene transcription as an enhancer (Figure S4). Silent mutations of the RelA CDS at the putative binding site of miR-221/222 diminished the effects of miR-221/222 on RelA protein expression, indicating direct binding of miR-221/222 to rela mRNA. The exact mechanisms by which miRNAs stabilize mRNA need to be further investigated. Nevertheless, this adds to the complexity of the spectrum of miRNA regulation on protein expression.

In summary, we show that there is a miR-221/222-mediated positive feedback loop, which plays important roles in maintaining constitutive activation of NF-κB and STAT3 pathways. The relevance of the positive feedback loop in inflammation-associated human CRC development and progression will provide a link between inflammatory signaling and oncogenic addiction. Disruption of the feedback loop with miR-221/222 inhibitors suppresses tumor cell growth, thus providing a potential new therapeutic approach for human CRCs.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Both canonical and non-canonical NF-κB were constitutively activated in colon cancer

(A-B) Immunohistochemical staining for RelA and RelB were performed using multiple tissue microarrays containing paired human colorectal normal and cancer tissues from 40 patients. Representative images of RelA and RelB staining in normal and cancer tissues were shown in (A), and a summary of the results was shown in (B).

(C) Correlation between the expression levels of RelA and RelB derived from 40 colorectal carcinoma.

(D-E) RelA and RelB protein (D) and mRNA (E) levels in different CRC cell lines. Normal colon cell line CCD-18Co was used as control.

Figure S2. The activation of non-canonical NF-κB pathway partially depends on canonical NF-κB pathway in CRC cells

(A) RelA, RelB, TRAF2, NIK, and p100/p52 protein levels in three stable shRelA HCT116 cells.

(B-F) Nuclear protein (B), total protein (C and D) and mRNA (E and F) levels of RelA, RelB, and non-canonical NF-κB related genes in HCT116 cells (C and E) or Lovo cells (D and F) overexpressing or knocking down RelA.

Figure S3. Reduced expression of RelB with miR-221/222 antisense was mediated by RelA

RelB mRNA in HCT116 cells (A) and RelB protein in 293T cells (B) after transfected with or without miR-221/222 and wild type or mutated RelA for 48 hours.

Figure S4. RelA transcription was not regulated by miR-221/222

(A) RelA 5′ UTR luciferase activity in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 mimics or antisense for 48 hr.

(B) RelA CDS luciferase activity in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense or mimics for 48 hr.

(C) Luciferase activity of pGL3-promoter-RelA CDS (800bp) in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-221/222 mimics for 48 hr.

Figure S5. miR-221/222 specifically regulate RelA rather than RelB or IKKβ

mRNA (upper panel) and protein (bottom panel) levels of RelA, RelB and IKKβ in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr.

Figure S6. RelA, STAT3 and their target genes were negatively regulated by PDLIM2

(A and B) The protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels of RelA, STAT3, and their target genes in RKO cells transfected with or without Flag-PDLIM2 plasmid for 72 hr.

Figure S7. PDLIM2 was restored by miR-221/222 inhibitor rather than methylation inhibitor

PDLIM2 mRNA levels in RKO cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr then treated with or without 5 aza-dC (5 μM) for 24 hr.

Figure S8. STAT3 level was elevated in colon cancer cells

(A) STAT3, Phospho-RelA (S536) (p-RelA), and acetylated RelA (K310) (Acy-RelA) in different colon cancer cell lines.

(B) STAT3 mRNA levels in different colon cancer cell lines. Normal colon fibroblast cell line CCD-18Co was used as control.

Figure S9. RelA knockdown inhibits colorectal cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo

(A)The growth curve of HCT116 cells with shRelA and shTGFP.

(B) The MTT results of shRelA and shTGFP in HCT116 cell line.

(C) shRelA blocked the HCT116 cell mitosis in S phase.

(D) Colony formation assay in HCT116 cells stably expressing shTGFP or shRelA. Colonies were counted after 10 days.

(E) Soft agar colony formation assay in HCT116 cells stably expressing shTGFP or shRelA. Colonies were counted after 28 days.

(F) Tumor growth in mice injected with HCT116 cells stably expressing shTGFP or shRelA.

(G-H) Tumor volume (G) and weight (H) in mice injected with HCT116 cells stably expressing shTGFP or shRelA (n = 5).

(I) Expression of related genes in shTGFP or shRelA tumor cells. (J) miR-221/222 expression in shTGFP or shRelA tumor cells.

(K) The immunohistochemistry results of Ki67, RelA and RelB in shTGFP or shRelA tumor cells, bar = 50μm.

(L) The protein levels of RelA, RelB, p100/p52 and p27 in shTGFP or shRelA tumor cells.

Figure S10. miR-221, miR-222, RelA, STAT3 and PDLIM2 levels in human colorectal cancer and normal tissues

(A) Assessment of miR-221, miR-222 levels (mean ± SD) by real-time PCR analysis in total RNAs and RelA, STAT3, and PDLIM2 protein levels by Western blot in 23 paired normal colon tissues and colorectal carcinomas, according to their tumor stage.

(B) Assessment of miR-221, miR-222 levels (mean ± SD) by real-time PCR analysis in total RNAs and RelA, STAT3, and PDLIM2 protein levels by Western blot derived from 9 paired normal colon tissues and colorectal carcinomas, according to their tumor stage.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (90919017 and 30972695), the National Basic Research Program (2011CB946102), Knowledge Innovation Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX1-YW-22), and National Key Programs on Infectious Disease (2008ZX10002-014). We would like to thank Drs. B. Li, Q. Zhai, Z. Lou, Y. Chen, J Han and A Chariot for antibodies and plasmids, Y. Liu and H. Wei for discussions, Q. Jing for support.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Extended Experimental Procedures, ten figures, and one table.

References

- 1.Grivennikov S, Karin M. Autocrine IL-6 signaling: a key event in tumorigenesis? Cancer cell. 2008;13:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terzić J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, et al. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2101–2114. e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karin M. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2009. NF-κB as a critical link between inflammation and cancer; p. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. Article| PDF (271 K) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-κB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka T, Grusby MJ, Kaisho T. PDLIM2-mediated termination of transcription factor NF-κB activation by intranuclear sequestration and degradation of the p65 subunit. Nature immunology. 2007;8:584–591. doi: 10.1038/ni1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H, Herrmann A, Deng JH, et al. Persistently activated Stat3 maintains constitutive NF-κB activity in tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qu Z, Yan P, Fu J, et al. DNA Methylation–Dependent Repression of PDZ-LIM Domain–Containing Protein 2 in Colon Cancer and Its Role as a Potential Therapeutic Target. Cancer research. 2010;70:1766–1772. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, et al. IKKβ links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu T, Sathe SS, Swiatkowski SM, et al. Secretion of cytokines and growth factors as a general cause of constitutive NFκB activation in cancer. Oncogene. 2003;23:2138–2145. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heneghan HM, Miller N, Kerin MJ. Systemic microRNAs: novel biomarkers for colorectal and other cancers? Gut. 2010;59:1002–1004. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng EK, Chong WW, Jin H, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer: a potential marker for colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2009;58:1375–1381. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.167817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kojima M, Morisaki T, Sasaki N, et al. Increased nuclear factor-kB activation in human colorectal carcinoma and its correlation with tumor progression. Anticancer research. 2004;24:675–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaked H, Hofseth LJ, Chumanevich A, et al. Chronic epithelial NF-κB activation accelerates APC loss and intestinal tumor initiation through iNOS up-regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:14007–14012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211509109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu HG, Yu LL, Yang Y, et al. Increased expression of RelA/nuclear factor-κB protein correlates with colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncology. 2003;65:37–45. doi: 10.1159/000071203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu HG, Zhong X, Yang YN, et al. Increased expression of nuclear factor-κB/RelA is correlated with tumor angiogenesis in human colorectal cancer. International journal of colorectal disease. 2004;19:18–22. doi: 10.1007/s00384-003-0494-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamagishi M, Nakano K, Miyake A, et al. Polycomb-mediated loss of miR-31 activates NIK-dependent NF-κB pathway in adult T cell leukemia and other cancers. Cancer cell. 2012;21:121. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chauhan D, Singh AV, Brahmandam M, et al. Functional interaction of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with multiple myeloma cells: a therapeutic target. Cancer cell. 2009;16:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo F, Tänzer S, Busslinger M, et al. Lack of nuclear factor-κB2/p100 causes a RelB-dependent block in early B lymphopoiesis. Blood. 2008;112:551–559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-125930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henke JI, Goergen D, Zheng J, et al. microRNA-122 stimulates translation of hepatitis C virus RNA. The EMBO journal. 2008;27:3300–3310. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pineau P, Volinia S, McJunkin K, et al. miR-221 overexpression contributes to liver tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:264–269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907904107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strebovsky J, Walker P, Lang R, et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) limits NFκB signaling by decreasing p65 stability within the cell nucleus. The FASEB Journal. 2011;25:863–874. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-170597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka T, Yamamoto Y, Muromoto R, et al. PDLIM2 inhibits T helper 17 cell development and granulomatous inflammation through degradation of STAT3. Science signaling. 2011;4:ra85. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collett GP, Campbell FC. Overexpression of p65/RelA potentiates curcumin-induced apoptosis in HCT116 human colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1285–1291. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nature methods. 2007;4:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prasad S, Ravindran J, Aggarwal BB. NF-κB and cancer: how intimate is this relationship. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2010;336:25–37. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felicetti F, Errico MC, Bottero L, et al. The promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger-microRNA-221/-222 pathway controls melanoma progression through multiple oncogenic mechanisms. Cancer research. 2008;68:2745–2754. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galardi S, Mercatelli N, Giorda E, et al. miR-221 and miR-222 expression affects the proliferation potential of human prostate carcinoma cell lines by targeting p27Kip1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:23716–23724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garofalo M, Di Leva G, Romano G, et al. miR-221&222 regulate TRAIL resistance and enhance tumorigenicity through PTEN and TIMP3 downregulation. Cancer cell. 2009;16:498–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.le Sage C, Nagel R, Egan DA, et al. Regulation of the p27Kip1 tumor suppressor by miR-221 and miR-222 promotes cancer cell proliferation. The EMBO journal. 2007;26:3699–3708. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li N, Tang B, Zhu ED, et al. IIncreased miR-222 in H. pylori-associated gastric cancer correlated with tumor progression by promoting cancer cell proliferation and targeting RECK. FEBS letters. 2012;586:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen R, Alvero A, Silasi D, et al. Regulation of IKKβ by miR-199a affects NF-κB activity in ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:4712–4723. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Z, Li Y, Takwi A, et al. miR-301a as an NF-κB activator in pancreatic cancer cells. The EMBO journal. 2010;30:57–67. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rokavec M, Wu W, Luo JL. IL6-mediated suppression of miR-200c directs constitutive activation of inflammatory signaling circuit driving transformation and tumorigenesis. Molecular Cell. 2012;45:777–789. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka T, Soriano MA, Grusby MJ. SLIM is a nuclear ubiquitin E3 ligase that negatively regulates STAT signaling. Immunity. 2005;22:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Place RF, Li LC, Pookot D, et al. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:1608–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orom UA, Nielsen FC, Lund AH. MicroRNA-10a binds the 5′ UTR of ribosomal protein mRNAs and enhances their translation. Molecular Cell. 2008;30:460–471. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forman JJ, Legesse-Miller A, Coller HA. A search for conserved sequences in coding regions reveals that the let-7 microRNA targets Dicer within its coding sequence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:14879–14884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803230105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, et al. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Both canonical and non-canonical NF-κB were constitutively activated in colon cancer

(A-B) Immunohistochemical staining for RelA and RelB were performed using multiple tissue microarrays containing paired human colorectal normal and cancer tissues from 40 patients. Representative images of RelA and RelB staining in normal and cancer tissues were shown in (A), and a summary of the results was shown in (B).

(C) Correlation between the expression levels of RelA and RelB derived from 40 colorectal carcinoma.

(D-E) RelA and RelB protein (D) and mRNA (E) levels in different CRC cell lines. Normal colon cell line CCD-18Co was used as control.

Figure S2. The activation of non-canonical NF-κB pathway partially depends on canonical NF-κB pathway in CRC cells

(A) RelA, RelB, TRAF2, NIK, and p100/p52 protein levels in three stable shRelA HCT116 cells.

(B-F) Nuclear protein (B), total protein (C and D) and mRNA (E and F) levels of RelA, RelB, and non-canonical NF-κB related genes in HCT116 cells (C and E) or Lovo cells (D and F) overexpressing or knocking down RelA.

Figure S3. Reduced expression of RelB with miR-221/222 antisense was mediated by RelA

RelB mRNA in HCT116 cells (A) and RelB protein in 293T cells (B) after transfected with or without miR-221/222 and wild type or mutated RelA for 48 hours.

Figure S4. RelA transcription was not regulated by miR-221/222

(A) RelA 5′ UTR luciferase activity in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-221/222 mimics or antisense for 48 hr.

(B) RelA CDS luciferase activity in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC or miR-221/222 antisense or mimics for 48 hr.

(C) Luciferase activity of pGL3-promoter-RelA CDS (800bp) in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-221/222 mimics for 48 hr.

Figure S5. miR-221/222 specifically regulate RelA rather than RelB or IKKβ

mRNA (upper panel) and protein (bottom panel) levels of RelA, RelB and IKKβ in HCT116 cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr.

Figure S6. RelA, STAT3 and their target genes were negatively regulated by PDLIM2

(A and B) The protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels of RelA, STAT3, and their target genes in RKO cells transfected with or without Flag-PDLIM2 plasmid for 72 hr.

Figure S7. PDLIM2 was restored by miR-221/222 inhibitor rather than methylation inhibitor

PDLIM2 mRNA levels in RKO cells treated with 100 nM miR-NC, miR-221/222 antisense for 48 hr then treated with or without 5 aza-dC (5 μM) for 24 hr.

Figure S8. STAT3 level was elevated in colon cancer cells

(A) STAT3, Phospho-RelA (S536) (p-RelA), and acetylated RelA (K310) (Acy-RelA) in different colon cancer cell lines.

(B) STAT3 mRNA levels in different colon cancer cell lines. Normal colon fibroblast cell line CCD-18Co was used as control.

Figure S9. RelA knockdown inhibits colorectal cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo

(A)The growth curve of HCT116 cells with shRelA and shTGFP.

(B) The MTT results of shRelA and shTGFP in HCT116 cell line.

(C) shRelA blocked the HCT116 cell mitosis in S phase.

(D) Colony formation assay in HCT116 cells stably expressing shTGFP or shRelA. Colonies were counted after 10 days.

(E) Soft agar colony formation assay in HCT116 cells stably expressing shTGFP or shRelA. Colonies were counted after 28 days.

(F) Tumor growth in mice injected with HCT116 cells stably expressing shTGFP or shRelA.

(G-H) Tumor volume (G) and weight (H) in mice injected with HCT116 cells stably expressing shTGFP or shRelA (n = 5).

(I) Expression of related genes in shTGFP or shRelA tumor cells. (J) miR-221/222 expression in shTGFP or shRelA tumor cells.

(K) The immunohistochemistry results of Ki67, RelA and RelB in shTGFP or shRelA tumor cells, bar = 50μm.

(L) The protein levels of RelA, RelB, p100/p52 and p27 in shTGFP or shRelA tumor cells.

Figure S10. miR-221, miR-222, RelA, STAT3 and PDLIM2 levels in human colorectal cancer and normal tissues

(A) Assessment of miR-221, miR-222 levels (mean ± SD) by real-time PCR analysis in total RNAs and RelA, STAT3, and PDLIM2 protein levels by Western blot in 23 paired normal colon tissues and colorectal carcinomas, according to their tumor stage.

(B) Assessment of miR-221, miR-222 levels (mean ± SD) by real-time PCR analysis in total RNAs and RelA, STAT3, and PDLIM2 protein levels by Western blot derived from 9 paired normal colon tissues and colorectal carcinomas, according to their tumor stage.