Abstract

Purpose

To compare the prevalence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with normal vision and with vision problems not correctable with glasses or contact lenses (vision problems) as determined by parent report in a nationwide telephone survey.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 75,171 children without intellectual impairment ages 4 to 17 participating in the 2011-12 National Survey of Children's Health (NSCH), conducted by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Demographic information and information regarding vision and ADHD status was obtained by parent interview. Questions asked whether they had ever been told by a doctor or health care provider that the child had a vision problem not correctable with glasses or contact lenses, ADHD, intellectual impairment or one of 13 other common chronic conditions of childhood. A follow-up question asked about condition severity. The main outcome measure was current ADHD.

Results

The prevalence of current ADHD was greater (p<0.0001) among children with vision problems (15.6%) compared to those with normal vision (8.3%). The odds of ADHD compared to that of children with normal vision was greatest for those with moderate vision problems (odds ratio (OR) 2.6 (95% CI 1.7, 4.4)) and mild vision problems (OR 1.8, 95% CI1.1, 2.9). Children with severe vision problems had similar odds of ADHD to that of children with normal vision, perhaps owing to the small numbers in this group (OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.8, 3.1). In multivariable analysis adjusting for confounding variables, vision problems remained independently associated with current ADHD (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2, 2.7).

Conclusions

In this large nationally representative sample, the prevalence of ADHD was greater among children with vision problems not correctable with glasses or contacts. The association between vision problems and ADHD remains even after adjusting for other factors known to be associated with ADHD.

Keywords: ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, National Survey of Children's Health, vision problems, vision impairment

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most frequently encountered neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. Among children ages 4 to 15 years in the 1999-2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 8.2% had parent-reported ADHD.1 The National Survey of Children's Health found that 10.1% of children in the 2007 survey 2 and 11% of children in the 2011-12 survey had parent reported ADHD.3 Children with ADHD have difficulty maintaining focus and controlling their behavior; some exhibit hyperactivity. There is no single known cause for ADHD; both genetic and environmental factors are thought to play a role.4

Focus groups of parents of children with vision impairment revealed concerns about ADHD.5 Children with low vision seen in a vision rehabilitation clinic or attending a state school for the blind, both in Alabama, had a 22.9% prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, which is considerably higher than the general population.6 Another study found an increased prevalence of self-reported ADHD among people with vision impairment due to albinism.7

Several studies have elucidated a link between vision problems and ADHD. ADHD has been found to be associated with astigmatic refractive error.8,9 Other groups have found an association between convergence insufficiency and ADHD10, 11. This is a significant finding, as convergence insufficiency is a relatively common condition, affecting between 2.25% and 8.3% of elementary school children.12, 13 Additionally, symptoms of convergence insufficiency are closely related to symptoms of ADHD and those symptoms decreased after vision therapy to improve vergence movements.14 These symptoms include difficulty completing schoolwork and inattentiveness during reading among others.10 The complex relationship of vision to ADHD is further evidenced by the finding of early deficits in visual sensory integration using event-related potentials measured in the visual cortex of children with ADHD15 as well as deficient blue color perception in adults with ADHD.16

The present study sought to utilize the dataset from the NSCH 2011-12 to examine the association between vision problems that are not correctable with glasses or contact lenses and ADHD.17

METHODS

NSCH Design

The NSCH is designed to examine factors related to the physical and emotional well-being of children ages 0-17 years in order to provide both state and national level estimates of child health.17 It is a random digit dialed telephone survey conducted in six languages (English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Vietnamese and Korean) by the National Center for Health Statistics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) using the CDC's State and Local Area Integrated Telephone System (SLAITS). The NSCH sampling is structured to obtain representative populations of children ages 0-17 in each state with a goal of at least 1800 children per state. In multi-child households one child was randomly selected to be the subject of the interview. A parent or guardian living in the household who had the most knowledge about the study child's health and healthcare was interviewed. The 2011-12 NSCH included responses about 95,677 children. Questions were divided into 13 sections: initial demographics, health and functional status, health insurance coverage, health care access and utilization, medical home, early childhood (ages 0-5 years), middle childhood and adolescence (6-17 years of age), family functioning, parental health, neighborhood characteristics, additional demographic characteristics, additional health insurance questions and locating information. Data collection was conducted under contract by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago and adhered strictly to the confidentiality and privacy regulations of the National Center for Health Statistics. Respondents were informed that participation was voluntary, that they may choose not to answer any questions they do not wish to answer and that their privacy is protected by Federal Law, but did not provide written consent. The database is publicly available on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm and contains no personal identifiers.17 None of the authors participated in survey design or data collection. Local Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study.

Study Variables

Questions about a wide range of health conditions and disorders including ADHD and vision problems were asked about all NSCH children aged two years and older. Disorder specific inquiries followed a three-question format. 1) “Has a doctor or health care provider you ever told you your child has [condition] even if they don't have it now?” 2) “Does the child currently have the [condition]?” 3) “Would you describe [his/her] [condition] as mild, moderate or severe?” Definitions of severity were not given during survey administration; responses were based on parent perception. The vision specific question asks about vision problems that cannot be corrected with standard glasses or contact lenses. Children whose parents responded affirmatively to this question were categorized as non-refractive vision problems (hereafter referred to as “vision problems”). The questions are structured similarly for ADHD with accompanying explanatory prompts provided. Within the ADHD series, an additional question asked if the child with current ADHD was taking medication for the condition. Specific wording for Survey questions and responses that were analyzed in this study can be found in the Appendix, available at [LWW insert link]. Children were categorized as having ADHD using parent report of ADHD diagnosed by a doctor or other health care provider. No clinical confirmations of ADHD or vision problems were obtained. A population level estimate of prevalence and a within group estimate of severity (mild, moderate, severe) was created from these questions for ADHD and vision problems.

A number of socio-demographic factors have been associated with ADHD and were included as potential confounders. Age of mother and child was classified by NSCH to the nearest year. Responses to race and ethnicity questions were combined to create four groups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic and Other (comprised of all other responses including mixed race). Children with birth weight less than 88 ounces (2500 grams) were categorized as having low birth weight. Children born more than three weeks early were considered premature. The primary language spoken in the household was dichotomized as English or other language. Family household structure was dichotomized as two parent biological or adoptive households, versus other household types. The total number of children under 18 in the family was classified as a categorical variable of one, two or three or more children. Poverty status (based on income and family size) was categorized into 2 groups based upon income at or above 200% or less than 200% above the federal poverty level. Family member smoking status was dichotomized as at least one smoker in the household or no smokers, highest level of education by either parent or main guardian in the household was dichotomized as high school or less or more than high school. Having health insurance was dichotomized as yes or no. Region of the US was categorized as North East, South, West and Midwest per the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration. Residence in a Metropolitan Statistical Area is determined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. This variable was dichotomized as yes or no.

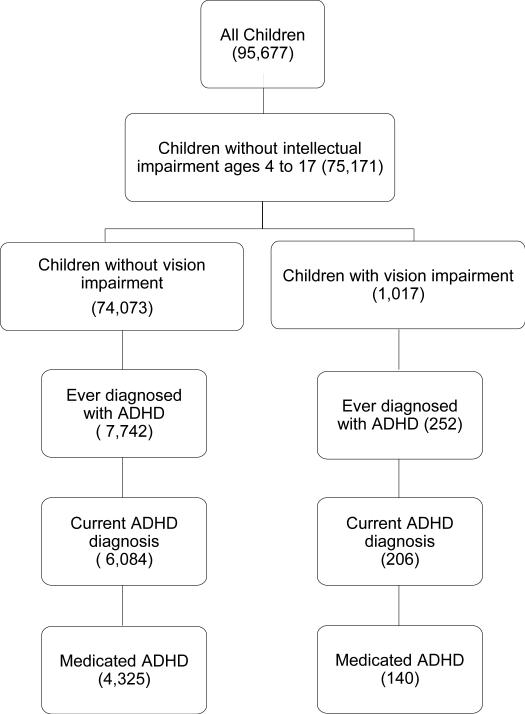

The current study cohort includes 75,151 children aged 4-17 years from the publicly available NSCH 2011-2012 dataset for whom the responding adult denied that a doctor or other health care provider ever told them that the child had intellectual disability or mental retardation (see the Appendix, available at [LWW insert link], for wording of question). The sample included an un-weighted group of 1,017 children with vision problems and 74,073 children without vision problems (Figure 1). Children with intellectual impairment were excluded, as diagnosis of ADHD requires that the behaviors be inappropriate for age, and intellectual impairment could confound the diagnosis.18 Children less than 4 were omitted since the American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline for ADHD evaluation is only established for children 4 to 18 years of age.19

Figure 1.

Description of the un-weighted sample within the National Survey of Children's Health.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted accounting for the sample design and weighting by methods suggested by the National Center for Health Statistics 20 using SAS v9.3 Survey Methods (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Base weighting accounts for the probability of selection of each phone number from others in the bank of numbers. The base weights are adjusted for non-resolution of telephone lines, non-response, sub-sampling by age-eligibility, multiple phone lines and non-coverage of children in households with no land-lines. Next, raking adjustments are used to match each state's weighted survey responses to selected characteristics of the state's population of non-institutionalized children ages 0 to 17 years. As a consequence, estimates reflect the national population of non-institutionalized children. We report un-weighted sample sizes and percentages as well as weighted percentages and weighted 95% confidence intervals. Chi- square and t-tests were used as appropriate. Variance estimates used the Taylor linearization method. “Don't know” and missing responses were denoted as missing and not included in the analysis. Univariate and multivariate logistic or ordinal regression was used to calculate p-values and odds ratios for both dichotomous (vision problems, yes or no) and multi-level (vision problems severity) variables. Weighted t-tests were used in univariate analysis of continuous variables. Adjusted odds ratios were calculated with all statistically significant univariate variables included in the model. Significance was set at α < 0.05.

RESULTS

In the weighted analyses of US children without intellectual disability between 4 and 17 years of age, 1.5% were estimated to have parent-reported vision problems not correctable with standard glasses or contact lenses. Among children in this cohort 8.4% (95% CI 8.0, 8.8) were estimated to have a current diagnosis of ADHD. Children with vision problems account for an estimated 2.7% (95% CI 2.0, 3.4) of children with current ADHD. Children with vision problems were more likely to have a current diagnosis of ADHD than those without vision problems (15.6% vs. 8.3%; p<0.001). Children with vision problems were also more likely to have ever been diagnosed with ADHD (18.6% vs. 10.4%; p<0.001). For those with ADHD, children with vision problems were not more or less likely to receive medication for the condition (64.4% vs. 69.0%; p=0.46).

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for all children, according to vision problem status. The percentage of males was greater in the group with vision problems (58.8% vs. 50.9%; p=0.02). There was no difference in the prevalence of low birth weight between those with or without vision problems, however, those with vision problems were significantly more likely to be born 3 or more weeks prematurely (p<0.001). Families with children who have vision problems appear different in some respects to other US families. Children with vision problems were more likely to have family income less than 200% above the poverty line than children without vision problems (p=0.0002). Children with vision problems were more likely to have a family structure including 2 adoptive or biological parents (p=0.003) and to have at least one smoker in the household (p=0.02). However, they were similar to children without vision problems in many aspects, including race/ethnicity, primary language in the home being English, parental education and region of the U.S. where they resided as well as whether or not they resided in a Metropolitan Statistical Area. In multivariable analysis adjusting for the potential confounding variables in Table 1 (sex, premature birth, family structure, smoker in the family, and poverty level), having a vision problem was independently associated with current ADHD (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2, 2.7).

Table 1.

Association of ADHD and demographic variables with vision problems not correctable with glasses or contact lenses.

| Variable | Children with Vision Problems n = 1,017 | Children without Vision Problems n = 74,073 | Weighted* Estimate for Children with Vision Problems n= 840,922 | Weighted* Estimate for Children without Vision Problems n =56,380,570 | Weighted* t-test or chi-square p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SE) | 11.3 (0.12) | 10.7 (0.02) | 11.4 (0.03) | 10.5 (0.03) | <.001 |

| Male, n (%, SE) | 598 (58.9) | 38,089 (51.5) | 493,490 (58.8, 3.4) | 28,648,022 (50.9, 0.4) | .02 |

| Race | |||||

| Hispanic, n (%, SE) | 135 (13.5) | 9,421 (13.0) | 227,390 (27.2, 3.9) | 12,527,348 (22.8, 0.4) | .24 |

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%, SE) | 663 (66.6) | 48,203 (66.6) | 412,643 (49.4, 3.6) | 29,248,999 (53.3, 0.4) | .28 |

| Non-Hispanic Black, n (%, SE) | 96 (9.6) | 6,958 (9.6) | 96,056 (11.5, 2.0) | 7,635,610 (13.9, 0.3) | .27 |

| Other, n (%, SE) | 110 (11.0) | 7,828 (10.8) | 99,888 (11.9, 2.8) | 5,471,113 (10.0, 0.2) | .44 |

| Low birth weight, n (%,SE) | 219 (21.5) | 9,921 (13.4) | 164,978 (19.5, 2.5) | 8,105,744 (14.4, 0.3) | .21 |

| Premature birth, n (%,SE) | 220 (22.0) | 8,035 (11.0) | 189,689 (22.8, 2.8) | 6,164,764 (11.0. 0.3) | <.001 |

| Family Structure* Two adoptive or biological parents | 295 (29.6) | 17,128 (23.4) | 305,791 (36.6, 3.2) | 14,749,452 (26.5, 0.4) | .003 |

| Number of children in household | |||||

| 1, n (%, SE) | 431 (42.4) | 28,999 (39.2) | 207,225 (24.6, 2.9) | 11,880,345 (21.1, 0.3) | .52 |

| 2, n (%, SE) | 343 (33.7) | 28,612 (38.8) | 252,285 (30.0, 2.8) | 21,846,076 (38.7, 0.4) | .004 |

| 3 or more, n (%, SE) | 243 (23.9) | 16,462 (22.2) | 381,413 (45.4, 3.7) | 22,654,149 (40.2, 0.4) | .16 |

| English primary language in home, n (%, SE) | 70 (6.9) | 5,328 (7.2) | 130,066 (15.5, 2.9) | 8,174,954 (14.5, 0.4) | .74 |

| Mother's age mean, n (mean, SE) | 836 (41.4, 0.26) | 67,292 (41.1, 0.26) | 744,962 (40.6, 0.6) | 51,225,788 (39.1) | .02 |

| Parent attended college or higher, n (%, SE) | 503 (52.3) | 36,218 (50.9) | 460,576 (58.3, 3.5) | 29,424,401 (35.2, 0.4) | .38 |

| Smoker in the family, n (%, SE) | 315 (31.3) | 17,042 (23.2) | 264,490 (31.6, 3.2) | 13,593,074 (24.4, 0.4) | .02 |

| Poverty level <200%, n (%, SE) | 500 (49.2) | 27,838 (37.6) | 509,050 (60.5, 3.3) | 26,051,864 (47.6, 0.4) | <.001 |

| Has health insurance, n (%, SE) | 979 (96.4) | 70,626 (95.5) | 799,863 (95.1, 1.6) | 52,920,979 (94.1, 0.2) | .34 |

| Region of US | |||||

| No East (Regions 1, 2, 3), n (%, SE) | 255 (25.1) | 20,527 (27.7) | 170,910 (20.3, 2.4) | 12,423,828 (20.0, 0.2) | .49 |

| West (Regions 8, 9, 10), n (%, SE) | 257 (25.3) | 20,034 (27.05) | 213,335 (25.4, 3.8) | 13,273,622 (23.5, 0.3) | .62 |

| South (Regions 4, 6)), n (%, SE) | 301 (29.6) | 18,891 (25.5) | 281,258 (33.4, 3.4) | 18,579,623 (32.9, 0.3) | .89 |

| Midwest (Regions 5, 7)), n (%, SE) | 204 (20.1) | 14,621 (19.7) | 175,420 (20.9, 2.4) | 12,103,497 (21.5, 0.2) | .80 |

| Residence in a Metropolitan Statistical Area), n (%, SE) | 187 (25.1) | 10,887 (21.8) | 125,952 (16.3, 2.0) | 7,715,728 (15.5, 0.3) | .68 |

| Ever told has ADHD, n (%, SE) | 252 (24.8) | 7,742 (10.5) | 156,383 (18.6, 2.2) | 5,872,289 (10.4, 0.2) | <.001 |

| Current ADHD, n (%, SE) | 206 (20.4) | 6,084 (8.2) | 130,121 (15.6, 2.0) | 4,660,602 (8.3, 0.2) | <.001 |

| Medicated ADHD, n (% of those with current ADHD, SE) | 140 (68.0) | 4,325 (71.1) | 83,796 (64.4, 6.3) | 3,224,641 (69.0, 1.4) | .46 |

Vision Problems = vision problems not correctable with glasses or contact lenses

Weighting methods used were those provided by the National Center for Health Statistics available at http://www.childhealthdata.org.

The associations of vision problems severity with current ADHD, the severity of ADHD and use of medication for ADHD were also evaluated (Table 2). Children with mild and moderate vision problems have increased odds of having current ADHD (OR 1.8, 95% CI (1.1, 2.9) and OR 2.6, 95% CI (1.6, 4.1), respectively) compared to children without vision problems. Children with severe vision problems were not at increased risk to have current ADHD (OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.8, 3.1). All levels of vision problems had increased odds of being in a more severe ADHD category (as rated by parent report) compared to children without vision problems. The odds of being in a more severe ADHD category were greatest for those with mild vision problems (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2, 3.0) and with moderate vision problems (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.7, 4.4) compared to their peers with normal vision. While children with severe vision problems have increased odds of more severe ADHD level, the difference is not statistically different. No significant associations were found between the severity of vision problems and the use of medication for ADHD.

Table 2.

Unadjusted associations between ADHD and vision problem severity.

| Mild VP OR (95% CI) | Moderate VP OR (95% CI) | Severe VP OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Level ADHD | 1.8 (1.1, 2.9) | 2.6 (1.6, 4.1) | 1.6 (0.8, 3.1) |

| Severity ADHDa | 1.9 (1.2, 3.0) | 2.8 (1.7, 4.4) | 1.6 (0.8, 3.3) |

| Medicated ADHD | 1.4 (0.6, 3.0) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.2) | 1.3 (0.4, 3.4) |

Reference group: No vision problems

Ordinal regression, odds of being in higher ADHD severity category

VP = vision problems not correctable with glasses or contact lenses

Table 3 examines only those children with ADHD and compares the odds ratios for children with vision problems to those without for many factors thought to be associated with ADHD. Children with vision problems and ADHD were similar to their normally sighted peers with ADHD with respect to sex, family member smoking status, language spoken at home, healthcare coverage, and family structure. Children with vision problems and ADHD, however were less likely to report Hispanic and more likely to report “other” as their race/ethnicity compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Adjusting for all factors that were significant at the univariate level yielded similar results.

Table 3.

Odds of Vision Problems among Children with Current ADHD.

| Variable | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (LCL, UCL) | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (LCL, UCL) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.97 (0.90, 1.04) | .41 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female (ref) | 1.0 | |||

| Male | 0.74 (0.43, 1.28) | .28 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Hispanic | 1.71 (0.80, 3.68) | .08 | 0.32 (0.14, 0.77) | .001 |

| African American | 0.32 (0.14, 0.73) | <0.001 | 1.27 (0.64, 2.48) | .28 |

| Other | 2.04 (0.97, 4.26) | .02 | 1.91 (0.87, 4.18) | .02 |

| Low Birth Weight | ||||

| ≥ 2500g (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| < 2500g | 2.50 (1.40, 4.60) | <.001 | 1.83 (0.92, 3.63) | .08 |

| Premature birth | ||||

| > 37 weeks gestation (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| ≤ 37 weeks gestation | 2.80 (1.60, 5.00) | .003 | 2.09 (1.04, 4.20) | .04 |

| Family structure | ||||

| 2 parent biological/ adoptive/step (ref) | 1.0 | |||

| Single mother/father/other | 0.69 (0.41, 1.18) | .18 | ||

| Number of children in household | ||||

| 1 (ref) | 1.0 | |||

| 2 | 0.72 (0.39, 1.33) | .53 | ||

| 3 or more | 0.74 (0.40, 1.37) | .63 | ||

| English primary language at home | ||||

| No (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 3.12 (0.96, 10.14) | .06 | 1.41 (0.41, 4.85) | .58 |

| Mother's age | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | .71 | ||

| Highest education level in household | ||||

| High school or less (ref) | 1.0 | |||

| More than high school | 0.74 (0.44, 1.26) | .27 | ||

| Smoker in the family | ||||

| No (ref) | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 1.25 (0.72, 2.13) | .44 | ||

| Family income | ||||

| > 200% poverty level (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| ≤ 200% poverty level | 1.64 (0.98, 2.76) | 0.6 | 1.63 (0.96, 2.76) | 0.7 |

| Region of US | ||||

| Midwest (Regions 5,6) (ref) | 1.0 | |||

| North East (Regions 1,2,3) | 1.08 (0.50, 2.35) | .61 | ||

| West (Regions 8,9,10) | 0.68 (0.30, 1.52) | .24 | ||

| South (Regions 4,6) | 1.07 (0.59, 1.94) | .53 | ||

| Residence in a Metropolitan Statistical Area | ||||

| No (ref) | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 1.02 (0.56, 1.85) | .46 | ||

| Currently medicated for ADHD | ||||

| No (ref) | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 0.81 (0.47, 1.41) | .46 | ||

LCL: 95% Lower Confidence Limit; UCL: 95% Upper Confidence Limit; ref: reference group

DISCUSSION

Results from this large national survey of children's health suggest an increased risk of ADHD among children with vision problems relative to other children. The prevalence of ADHD among children with vision problems from this national cross-sectional study is similar to that previously reported among children with low vision in a vision rehabilitation clinic in Alabama6 (18.6% vs. 22.9%, respectively). Likewise, the prevalence of ADHD among children without a vision problem is similar to that found in other national studies (8.3% in this study compared to 8.2% in the NHANES). Importantly, diagnosis in the NHANES was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4 criteria and included clinical examination.

Although there were differences between the participants with vision problems and those without vision problems, none of those differences have been established as causes of ADHD. The cause of ADHD is still unknown and likely multi-factorial involving both genetic and environmental influences. Many factors have been found to be associated with ADHD such as maternal and paternal smoking during pregnancy, low birth weight, blood lead level, as well as family history of ADHD.4 Here we provide evidence that vision problems are also independently associated with ADHD. Since the question regarding vision problems was non-specific, it is likely that parents responded affirmatively for many types of vision problems such as monocular vision loss, color vision deficiency or strabismus as well as for conditions resulting in vision impairment, suggesting that many different types of vision problems may be associated with ADHD.

Children with convergence insufficiency have been shown to have an increased prevalence of ADHD.10, 21 Children with ADHD have been shown to have an increased frequency of ametropia and visuoperceptual problems.8 It is probable that some of the children with vision problems whose parents classified their condition as mild had binocular vision anomalies. The odds of ADHD are lower among those with mild vision problems than among children in the moderate vision problems group. Children with obvious signs of vision problems (such as strabismus or nystagmus) would likely be categorized by their parents as having a more severe vision problem. Since vision plays such an important role in acquiring information, it is easy to see how vision problems might impact attention and how more severe vision problems would have a greater effect.

It is likely that some children with vision problems are incorrectly identified as having ADHD. If children are unable to see something, they may not be able to keep their attention focused on it. Similarly, if they are struggling to see their work, they may have difficulty finishing in a timely manner. These problems may incorrectly be interpreted as ADHD. It is surprising and counterintuitive that the children with the most severe vision problems had increased odds of having ADHD but that the increase was not statistically significant (likely due to the small number of children in this category).

One intriguing possible explanation relates to utilization of executive function. Each individual has a finite amount of executive functioning (the higher order cognitive processes that enable people to plan, organize, pay attention and manage time and space).22 Impairment of executive functioning is implicated in ADHD.23 Individuals with a sensory deficit will necessarily need to use more of their executive functioning to compensate for that deficit, leaving less executive function in reserve to change or maintain an attentional state. This theory is supported by the odds of having ADHD as well as the odds of having more severe ADHD being greatest among those with moderate vision problems. Those with moderate vision problems would likely need to use the largest amount of executive functioning to compensate for their vision impairment, while those with mild vision problems would need less. Those with severe vision problems may use other tools in their daily activities such as magnification, Braille or a white cane for mobility and may use less executive function to compensate for their vision impairment.

This study has several limitations common to survey based health research. The NSCH is a telephone survey and although parents were asked to report if a doctor or other healthcare provider had made a diagnosis of ADHD or vision problems, their report was not validated. Additionally, there is no information available on the cause or type of vision problem or about which type of health care provider made the ADHD diagnosis. The PLAY Study (Project to Learn About ADHD in Youth) has shown that case definition has a significant impact when determining ADHD prevalence.24 Thus, the prevalence found in this study is impacted by the varying criteria used by the doctors or health care providers who reportedly made the diagnosis. To further emphasize the difficulty in assessing ADHD prevalence, the PLAY Study found that less than 40% of children medicated for ADHD in one school district in South Carolina and five school districts in Oklahoma actually met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 criteria for ADHD diagnosis.25 However, the opposite was found in a study utilizing data from the NHANES. Only 48% of children meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV criteria for ADHD according to a structured diagnostic interview had a parent-report of an ADHD diagnosis by a healthcare professional.26 There are undoubtedly both false positive and false negative reports of ADHD and/or vision problems in the dataset. The possibility of recall bias or intentional inaccurate reporting also exists.

A strength of this work is that the NSCH is a large national sample that was designed to be representative of non-institutionalized children in the U.S. and thus the results are generalizable. There is also evidence that parent report of ADHD has convergent validity with medical records and well-defined criteria.27 Although it would be preferable to have both psychological and optometric evaluations of the children, this data does strongly suggest that there is an association between vision problems and ADHD that merits further investigation.

In conclusion, there is an independent association between parent reported vision problems not correctable with standard glasses or contact lenses and ADHD even after adjusting for other factors known to be associated with ADHD. This finding suggests that children with vision problems should be monitored for signs and symptoms of ADHD so that this dual impairment of vision and attention can best be addressed. While eye care providers are not trained to diagnose nor treat ADHD, they should be aware that their patients with vision problems are at increased risk of having ADHD. If there is a suspicion of ADHD the primary care provider and/or a specialist in ADHD should be consulted. Future research should be directed toward longitudinal studies examining associations between type and severity of vision impairment and ADHD, the mechanisms underlying the association, as well as determining the most effective treatment strategies.

APPENDIX

Specific wording of questions regarding ADHD and vision problems in the 2011-2012 NSCH. The entire script for the Survey is available as at PDF at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/slaits/2011NSCHQuestionnaire.pdf

| Now I am going to read you a list of conditions. For each condition, please tell me if a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that [child] had the condition, even if [he/she] does not have the condition now. |

| • Intellectual disability or mental retardation? |

| • Attention Deficit Disorder or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; that is, ADD or ADHD? |

| • Vision problems that cannot be corrected with standard glasses or contact lenses? |

| Follow-up questions for ADHD: |

| Earlier you told me that [child] has been diagnosed with ADD/ADHD. |

| • Does [child] currently have ADD/ADHD? |

| YES |

| NO |

| DON'T KNOW |

| REFUSED |

| • Would you describe [his/her] ADD/ADHD as mild, moderate, or severe? |

| MILD |

| MODERATE |

| SEVERE |

| DON'T KNOW |

| REFUSED |

| • Is [child] currently taking medication for ADD or ADHD? |

| YES |

| NO |

| DON'T KNOW |

| REFUSED |

| Follow-up questions for vision problems: |

| Earlier you told me that [child] has been diagnosed with vision problems. |

| • Does [child] currently have vision problems that cannot be corrected with standard glasses or contact lenses? |

| YES |

| NO |

| DON'T KNOW |

| REFUSED |

| • (Asked only if answer to above question is “YES”) Would you describe [his/her] vision problems that cannot be corrected with standard glasses or contact lenses as mild, moderate, or severe? |

| MILD |

| MODERATE |

| SEVERE |

| DON'T KNOW |

| REFUSED |

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Previously presented in part as a poster at the American Academy of Optometry Annual Meeting 2013, Seattle Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braun JM, Kahn RS, Froehlich T, Auinger P, Lanphear BP. Exposures to environmental toxicants and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in U.S. children. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1904–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lingineni RK, Biswas S, Ahmad N, Jackson BE, Bae S, Singh KP. Factors associated with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among US children: results from a national survey. BMC Pediatr. 2012:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Ghandour RM, Perou R, Blumberg SJ. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003-2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:34–46. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, Langley K. Practitioner review: What have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? J Child Psychol Psyc. 2013;54:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decarlo DK, McGwin G, Jr., Bixler ML, Wallander J, Owsley C. Impact of pediatric vision impairment on daily life: results of focus groups. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:1409–16. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318264f1dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeCarlo DK, Bowman E, Monroe C, Kline R, McGwin G, Owsley C. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children, with vision impairment. J AAPOS. 2014;18:10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutzbach B, Summers CG, Holleschau AM, King RA, MacDonald JT. The prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among persons with albinism. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1342–7. doi: 10.1177/0883073807307078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gronlund MA, Aring E, Landgren M, Hellstrom A. Visual function and ocular features in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, with and without treatment with stimulants. Eye. 2007;21:494–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabian ID, Kinori M, Ancri O, Spierer A, Tsinman A, Ben Simon GJ. The possible association of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with undiagnosed refractive errors. J AAPOS. 2013;17:507–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Kulp MT, Scheiman M, Amster D, Coulter R, Fecho G, Gallaway M. Academic behaviors in children with convergence insufficiency with and without parent-reported ADHD. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:1169–77. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181baad13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borsting E, Rouse M, Chu R. Measuring ADHD behaviors in children with symptomatic accommodative dysfunction or convergence insufficiency: a preliminary study. Optometry. 2005;76:588–92. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letourneau JE, Ducic S. Prevalence of convergence insufficiency among elementary school children. Can J Optom. 1988;50:194–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouse MW, Borsting E, Hyman L, Hussein M, Cotter SA, Flynn M, Scheiman M, Gallaway M, De Land PN. Frequency of convergence insufficiency among fifth and sixth graders. The Convergence Insufficiency and Reading Study (CIRS) group. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:643–9. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Moon BY, Cho HG. Improvement of vergence movements by vision therapy decreases K-ARS scores of symptomatic ADHD children. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26:223–7. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nazari MA, Berquin P, Missonnier P, Aarabi A, Debatisse D, De Broca A, Wallois F. Visual sensory processing deficit in the occipital region in children with attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder as revealed by event-related potentials during cued continuous performance test. Neurophysiol Clin. 2010;40:137–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Chen S, Tannock R. Visual function and color vision in adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Optom. 2014;7:22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.optom.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [November 1, 2013];National Survey of Children's Health. 2013 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.

- 18.Antshel KM, Phillips MH, Gordon M, Barkley R, Faraone SV. Is ADHD a valid disorder in children with intellectual delays? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:555–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, Earls M, Feldman HM, Ganiats TG, Kaplanek B, Meyer B, Perrin J, Pierce K, Reiff M, Stein MT, Visser S. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1007–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.2011-2012 National Survey of Children's Health. SAS Code for Data Users: Child Health Indicator and Subgroups; Version 1.0. [November 1, 2013];Sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau. 2013 Available at: http://www.nschdata.org/docs/nsch-docs/sas-codebook_-2011-2012-nsch-v1_05-10-13.pdf?sfvrsn=1.

- 21.Granet DB, Gomi CF, Ventura R, Miller-Scholte A. The relationship between convergence insufficiency and ADHD. Strabismus. 2005;13:163–8. doi: 10.1080/09273970500455436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baddeley A. Exploring the central executive. Q J Exp Psychol (A) 1996;49:5–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rapport MD, Orban SA, Kofler MJ, Friedman LM. Do programs designed to train working memory, other executive functions, and attention benefit children with ADHD? A meta-analytic review of cognitive, academic, and behavioral outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1237–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKeown RE, Holbrook JR, Danielson ML, Cuffe SP, Wolraich ML, Visser SN. The impact of case definition on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder prevalence estimates in community-based samples of school-aged children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolraich ML, McKeown RE, Visser SN, Bard D, Cuffe S, Neas B, Geryk LL, Doffing M, Bottai M, Abramowitz AJ, Beck L, Holbrook JR, Danielson M. The prevalence of ADHD: its diagnosis and treatment in four school districts across two states. J Atten Disord. 2014;18:563–75. doi: 10.1177/1087054712453169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froehlich TE, Lanphear BP, Epstein JN, Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Kahn RS. Prevalence, recognition, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a national sample of US children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:857–64. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.9.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Perou R, Blumberg SJ. Convergent validity of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis: a cross-study comparison. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:674–5. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]