Abstract

South Africa has among the highest rates of HIV infection in the world, with women disproportionately affected. Alcohol-serving venues, where alcohol use and sexual risk often intersect, play an important role in HIV risk. Previous studies indicate alcohol use and gender inequity as drivers of this epidemic, yet these factors have largely been examined using person-level predictors. We sought to advance upon this literature by examining venue-level predictors, namely men’s gender attitudes, alcohol and sex behavior to predict women’s risks for HIV. We recruited a cohort of 554 women from twelve alcohol venues (6 primarily Black African, and 6 primarily Coloured [i.e., mixed race] venues) in Cape Town, who were followed for one year across 4 time points. In each of these venues, men’s (N=2,216) attitudes, alcohol use and sexual behaviors were also assessed. Men’s attitudes and behaviors at the venue level were modeled using multilevel modeling to predict women’s unprotected sex over time. We stratified analyses by venue race. As predicted, venue-level characteristics were significantly associated with women’s unprotected sex. Stratified results varied between Black and Coloured venues. Among Black venues where men reported drinking alcohol more frequently, and among Coloured venues where men reported meeting sex partners more frequently, women reported more unprotected sex. This study adds to the growing literature on venues, context, and HIV risk. The results demonstrate that men’s behavior at alcohol drinking venues relate to women’s risks for HIV. This novel finding suggests a need for social-structural interventions that target both men and women to reduce women’s risks.

Introduction

South Africa has the greatest number of people living with HIV/AIDS with more than 1 in 6 adults aged 15–49 infected (UNAIDS, 2011) and the highest HIV incidence rate in the world (HSRC, 2012). Among adults aged 15–49, HIV prevalence for women is over 23% compared to 13% among men, a gender difference of more than 10%. Women age 15 to 24 have an HIV incidence rate more than 4 times that of men, with a 4.5% incidence of HIV among Black African women (HSRC, 2012). Thus far, research has focused more on individual influences of HIV infections, rather than social-structural drivers. For example, it is well documented that individuals who consume more alcohol are at greater risk for HIV (Kalichman, Simbayi, Kaufman, Cain, & Jooste, 2007). As such, alcohol-serving venues (e.g., bars, taverns, or informal drinking places called “shebeens”) in South Africa represent settings where processes related to sexual risk taking, alcohol use, and gender intersect to potentially compound risk. As many as 94% of the places where South Africans meet new sex partners are places that serve alcohol (Weir, Morroni, Coetzee, Spencer, & Boerma, 2002). Not only is alcohol use a robust predictor of sexual risk for HIV (Kalichman et al., 2007), South Africans who drink alcohol consume it at a rate among the highest in the world (Parry et al., 2005). In addition, controlling for alcohol use, mere attendance at drinking venues is associated with greater sexual risk for HIV (Cain et al., 2012). These findings suggest that in order to best explain sexual risk, there are additional, critical venue related factors that must be examined.

Compared to men, alcohol-serving venues may be especially risky places for women, as men often direct and control women’s drinking and sexual behavior in such venues (Townsend et al., 2011; Watt et al., 2012). Further, in cases where sexual advances are not reciprocated, violence may ensue and may at times be seen as justifiable (Watt et al., 2012). This research suggests that men drive women’s risks in the context of alcohol-serving venues in South Africa. Based on prior literature, we know that South African women who attend alcohol-drinking venues are at elevated risk for HIV due to multiple factors. Yet, to our knowledge there is no previous research that has taken a multilevel modeling approach to understanding women’s sexual risks in relation to the social context of alcohol venues. Guided by Social Action Theory, which posits that at one level venues and settings serve as action contexts, and at a second level social interactions and interpersonal relationships influence health behaviors (Ewart, 1991, 2004, 2009), the current study addresses the research gap by examining the role of venue-level factors in influencing individual sexual risk behavior among women in alcohol venues in South Africa.

According to Social Action Theory, health protective behaviors, such as reducing numbers of sex partners and using condoms, are in part influenced by social interactions in social settings. Furthermore, existing gender inequalities mean that women are less able to dictate power to influence their own sexual health-related actions. HIV risks for women in male dominated contexts, such as drinking venues in South Africa, will therefore be predicted by the attitudes and actions of men in those environments. For example, in venues where men have more sexist attitudes, gender dynamics should be more restrictive or oppressive for women, which may translate into lower condom use for women. In venues where men report consuming more alcohol, women should also report less condom use. Studying social contextual factors that influence individuals’ behaviors therefore requires multilevel approaches to begin to unpack these complex social processes. Like gender, race plays a role in HIV risk, and is a critical factor in South Africa’s HIV epidemic (Gilbert & Walker, 2002; Kenyon, Buyze, & Colebunders, 2013).

Black Africans make up the majority of the South African population (79%) and have an HIV prevalence of 19.9%, while individuals of historically mixed race (i.e., “Coloured”) make up 9% of the population and have an HIV prevalence of 3.2%. During apartheid the two groups were geographically segregated from Whites and from each other. Blacks and Coloureds have historically differed in terms of culture, language, and status in South Africa. Although communities today are more racially integrated, it is not uncommon for Blacks and Coloureds to live in different areas of the same community, and to attend different social establishments (Christopher, 2001; Tredoux & Dixon, 2009). Accordingly, the venues included in our study were systematically selected based on their attendance by primarily Black or Coloured patrons. Our overall aim in the current study is to examine the multilevel association between venue-level social factors – specifically the gender-related attitudes, substance use, and sex behaviors of the male patrons – and female patrons’ condom unprotected sex across twelve alcohol-serving venues in Cape Town, South Africa. We hypothesized that in venues where men have more sexist attitudes and higher substance use and sexual risk behaviors, the women in those venues would report less condom use. Results of this study have the potential to inform interventions aimed to target men’s behaviors in alcohol venues in order to reduce women’s risks for HIV.

Method

Study Overview

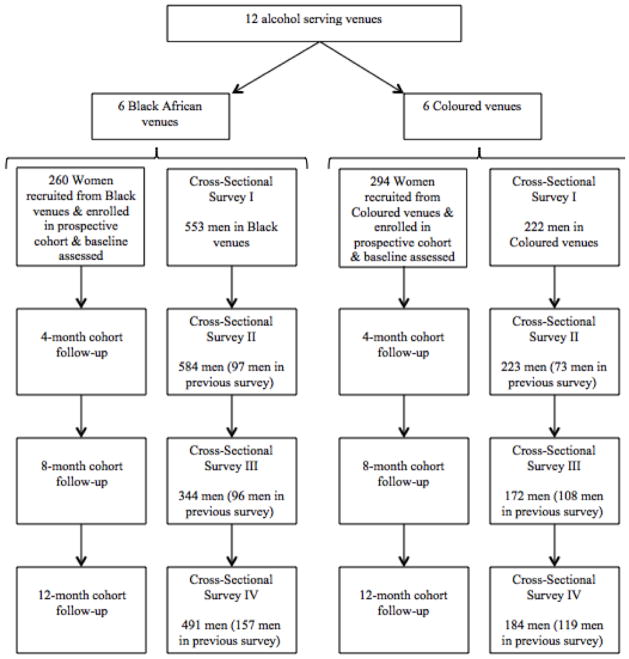

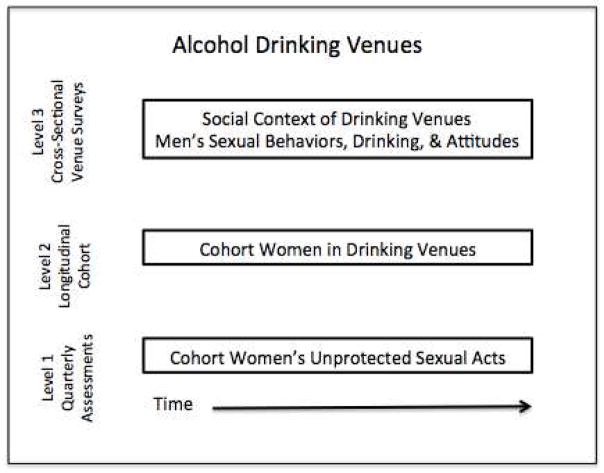

Data collection took place between October 2009 and May 2012 in a peri-urban township located within 20 kilometers of Cape Town, South Africa. The township consists of Coloureds and Black Africans living in separate adjacent areas. Participants included a prospective cohort of 560 women recruited from 12 different alcohol-serving venues who were assessed four times over the course of one year. In addition to prospective cohort assessments, during the course of the study we also surveyed patrons in the 12 venues. As part of the overall research project both male and female patrons were surveyed, however for the purpose of this study we focus on venue surveys collected from male patrons only. Figure 1 portrays the general design of the current study, participant flow, and data sources. These data were structured at three levels used in multilevel modeling: measures of women’s sexual behavior across 4 time points were modeled at Level 1, the individual women were modeled at Level 2, and social contextual factors derived from surveys of men in venues were modeled at Level 3.

Figure 1.

Participant flow and data sources

Venue Selection

Using an adaptation of the Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts (PLACE) community mapping methodology (Weir et al., 2002), we located and defined alcohol serving establishments in the township for the current study. Alcohol serving venues in the township were systematically identified by approaching a total of 509 members of the community at public places such as bus stands and markets, and asking them to identify places where people go to drink alcohol. Identified venues included both small unlicensed venues (i.e., shebeens), and larger licensed venues (i.e., taverns). The research team visited 172 identified venues to assess for study eligibility. Venues were eligible if they had space for patrons to sit and drink, reported at least 50 unique patrons per week, had a minimum of 10% female patrons, and were willing to have the research team visit over the course of a year. Forty venues were identified as eligible and were ranked on the number of patrons, proportion of female patrons, and primary racial composition; 12 were selected that represented both small and large venues geographically dispersed throughout the township. Managers at each venue issued permission for the study activities. The 12 identified venues included six predominantly attended by Coloured patrons and six predominantly attended by Black African patrons. A fieldwork team of six South Africans (two Black African women, one Black African man, two Coloured women, and one Coloured man) collected all study data. Field workers were matched to the venues by race and language. Individual field workers approached venue patrons upon entering the venue.

Women’s Cohort Recruitment and Procedures

Following a week of ethnographic observations, we invited female patrons in the venue to be part of a cohort study to examine drinking and sexual behavior over the course of one year. Fifty women from each venue were invited to participate, with greater than 95% agreement. Written informed consent was obtained from those interested in participating. Women were eligible for the study if they were (a) at least 18 years of age; (b) drank in the venue; and (c) lived in the township. Project staff located in a research field office established in the township conducted screening. A total of 604 women were approached to participate and given an appointment card to come to the study office to provide informed consent and complete an initial assessment. Almost all (560, 92.7%) came for the initial appointment and enrolled in the study.

Women’s Measures Collected in Cohort

Measures were administered using audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) delivered in the participants’ preferred language – English, Xhosa, and Afrikaans, the three languages spoken by persons in the township. Research has shown that ACASI procedures yield reliable responses in sexual behavior interviews (Gribble, Miller, Rogers, & Turner, 1999; Turner, Ku, Sonenstein, & Pleck, 1996). Participants were given a grocery store voucher (150ZAR, or approximately 20USD) at each time point.

We collected women’s age, education level, and race (participant identified as Coloured, Black, White, Indian, or other). Participants also indicated their marital status and current employment status (yes or no), and indicated yes or no to three indicators of socioeconomic status: having electricity, tap water, and/or a refrigerator in the home. We were interested in these variables in order to describe the sample.

Primary Outcome: Women’s Unprotected Sex (Level 1)

For our primary outcome measure, we assessed women’s sexual behavior. Participants used an open-response format to report the number of the following sexual acts during the past 4 months: number of unprotected vaginal sex acts (i.e., without condoms), number of protected vaginal sex acts (i.e., with condoms), unprotected anal sex acts, and protected anal sex acts. We used this format and time-frame to provide optimal recall and to avoid anchored responses (Napper, Fisher, Reynolds, & Johnson, 2010). We created the variable proportion unprotected sex by dividing total number of condom unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse acts by total number of protected and unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse acts. Women in the cohort completed assessments at four time points, at Time 0, and at 4, 8, and 12 months after the initial assessment. Therefore, in the multilevel models measurements of the outcome across time were modeled at Level 1.

Men’s Venue Recruitment and Procedures

At the same time points and from the same venues where women were recruited for the prospective cohort, field staff visited each of the twelve venues to administer cross-sectional anonymous surveys a total of four times over the course of the study. All the men and women were invited to complete a 9-page survey questionnaire, which took an average of 10–15 minutes to complete. Verbal consent was obtained. Participants were ensured privacy by being given a semi-private place to sit and complete the survey in the venue. When assistance was required (<5%), participants were read the survey questions and responded on their own survey forms. Participants were given a small token of appreciation for completing surveys, such as a keychain or coffee mug. A question on the survey asked whether the participants had taken the survey previously (redundant surveys were removed), but no identifiers linked the surveys over time.

Men’s Measures Collected at Venues (Level 3/Venue Predictors)

Venue-level variables were computed using data from the cross-sectional surveys given to male patrons in the 12 venues. Specifically, we surveyed the men on their sociodemographics, bar (venue) behaviors, alcohol use, drug use, gender attitudes, and sexual risk behavior. Then, we aggregated the men’s data within each venue and time point to compute the venue-level variables/predictors of women’s unprotected sex. For example, at each venue we computed men’s average alcohol consumption, and proportion of men who have met a new sex partner at the bar. Thus, the sample size for venue-level characteristics data were 48 (12 venues at 4 time points).

In terms of the specific venue-level variables, men were asked about their years of education (1 = grade 7 or less, 2 = grade 8–11, 3 = grade 12, and 4 = beyond grade 12). We computed variables that indicated the proportion of men who were surveyed relative to women, and men’s average education level. Men in the venues were also asked how often they came to that bar. Response options were: “This is my first time;” “A few times a year;” “Monthly;” “Weekly;” and “Almost daily.” In separate items participants were also asked to indicate “yes” or “no” to whether: they came to the bar to find a new sex partner, they have ever met a new sex partner at the bar, they used a condom the last time they met a sex partner at the bar, and whether they ever had sex on the bar premises. We computed venue variables that indicated the proportion of men who reported coming to the bar at least weekly, the proportion of men who came to find a sex partner, the proportion of men who have ever met a new sex partner there, the proportion who used a condom the last time they met a sex partner there, and the proportion of men who reported ever having sex on the bar premises.

Men in the venues were asked about their frequency and quantity of alcohol use and frequency of binge drinking using the consumption index on the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). Drinking frequency: Participants were asked to report how often they have a drink containing alcohol; response choices were 1 = never, 2 = monthly or less, 3 = 2–4 times a month, 4 = 2–3 times a week, and 5 = more than 4 times a week. Alcohol consumption quantity: Participants reported how many drinks containing alcohol they have on a typical day when they are drinking; response choices were 1 = I don’t drink, 2 = 1–2 drinks, 3 = 3–4 drinks, 4 = 5–6 drinks, 5 = 7–9 drinks and 6 = 10 or more. Binge drinking frequency: Participants were asked how often they have six or more drinks on a single drinking occasion; response choices were 1 = never, 2 = less than monthly, 3 = monthly, 4 = weekly, and 5 = daily or almost daily. We computed venue variables that indicated men’s average drinking frequency, quantity, and binge drinking frequency. Participants were also asked whether they used marijuana (i.e., cannabis or dagga) or methamphetamine (i.e., meth, Tik) in the past 4 months in separate items. Response choices were 1 = never, 2 = a few times, 3 = weekly, and 4 = daily. We computed venue variables that indicated the proportion of men in each venue who reported using any marijuana in the past 4 months and did the same for meth use.

To assess gender attitudes, men were asked to indicate agreement (yes=1 or no=0) with seven items about women that we developed and have used in previous research in South Africa (Kalichman et al., 2005). An example item is, “A woman who talks disrespectful to a man in public should expect trouble.” For each participant we summed the number of items to which they agreed. We computed a venue variable indicating the average of men’s sexist attitudes.

Sexual behaviors in men were assed using open-response formats to report the number of sex partners they had in the past 4 months, and the number of acts of unprotected vaginal sex, protected vaginal sex, unprotected anal sex, and protected anal sex they had in the same time period. We summed the total number of sex acts (protected or unprotected), total number of protected acts, and total number of unprotected acts. For each participant we created a variable proportion unprotected sex by dividing the total number of condom unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse by total protected and unprotected vaginal and anal acts. We computed venue variables that indicated men’s average number of sex partners, sex acts, unprotected sex acts, and proportion of unprotected sex. We also created the venue variable proportion unprotected men to include men who did not report any recent sex, in such cases men were coded as 0% unprotected. Our previous research has demonstrated that the variables described above play important roles in HIV risk among alcohol venue patrons in South Africa and were therefore carefully selected (Kalichman, Simbayi, Vermaak, Jooste, & Cain, 2008; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2012).

Statistical Analyses

Of the 560 women recruited into the cohort, six women (1%) completed only the initial assessment and were excluded from the current study. Towards the end of the data collection one of the venues experienced legal problems associated with their alcohol licensing status and was shut down before the 12-month cross-sectional patron surveys could be collected. Thus, venue 12 had missing data from men at the 12-month assessment. For each of the venue-level variables, we imputed the mean of the venue’s first three assessments to replace this venue’s missing data.

We examined descriptive statistics of the cohort women and of the venues. Specifically, we used SPSS version 19 to conduct one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables to examine demographics, alcohol use, and sexual behaviors among the cohort, and venue characteristics using male patron survey data. Given previous research suggesting different HIV risk and sexual behaviors between Coloureds and Blacks in South Africa, we stratified by venue race (i.e., Coloured and Black venues) to test the role of venue characteristics on cohort sexual risk behaviors over time. We also used multilevel modeling to account for the nesting structure of the data, which is displayed in Figure 2. Data at Level 3 were venue-level variables that characterized men’s attitudes and behaviors from the 12 venues (Coloured venues n=6, Black venues n = 6). Nested within that were the individual cohort women (Level 2; Coloured venues n=294, Black venues n=260). Data at Level 1 were measurements of the women’s sexual risk behavior across time (nested within persons) (Coloured venues n=1176, Black venues n=1040). All models were stratified by venue race. We tested univariate models of individual venue factors predicting women’s proportion of unprotected sex. We then tested for independent predictors of women’s unprotected sex in two multivariate models, one for Coloured and the other for Black venue participants. A total of 32 models were tested; 15 univariate models for each venue-level predictor for both Coloured and Black venues, and the two multivariate models. Multilevel modeling was conducted in Hierarchical Linear Modeling version 7 (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2001).

Figure 2.

Multilevel data structure

Thus, for our primary analyses, stratifying by venue race, we conducted multilevel models to test the association between venue-level variables and women’s sexual risk behavior over time. Time was coded as (0, 1, 2, 3) and was un-centered in the modeling. Venue-level variables were centered around the grand mean. The univariate regression models at each level that were tested for each model run were:

Level 1 Model: Women’s proportion of condom unprotected sex = Ψ0 + Ψ1 (Time) + error (This model tests whether the outcome varied across time)

-

Level 2 Models: Ψ0 = π00 + e0.

Ψ1 = π10 (These models are necessarily included to define the woman at Level 2)

-

Level 3 Models: π00 = β000 + β001(Venue-level variable) + r00

π10 = β100 (These models test the venue-level predictors on the outcome)

Thus, the composite multilevel regression model (after substituting terms) is:

Women’s proportion of condom unprotected sex = β000 + β001(Venue-level variable) + β100(Time) + e0 + r00 + error. Where β000 represents the grand intercept, or mean level of women’s proportion of condom unprotected sex at baseline when the venue-level variable is at the mean across venues, β001 represents the regression coefficient for the venue-level variable, and β100 represents the regression coefficient for time. The remaining terms represent remaining variance and error variance.

We did not enter Level 2 or 3 predictors of the effect of time (e.g., if venue-level factors moderated the impact of time on women’s unprotected sex). We made this decision because time-only models showed that there was no significant effect of time on women’s unprotected sex. We ultimately did not include Level 2 predictors to maximize power and because the focus was on venue-level predictors of individual risk. Predictors (or potential confounders) that were significant at p < .05 in univariate models were included in the multivariate models to determine independent correlates of women’s unprotected sex. We determined collinear variables by examining inter-correlations among predictors (see below) and removed them from the multivariate models.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics of Women in the Cohort

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of the women in the prospective cohort overall and differences by venue race. On average, the women were about 34 years of age (SD = 11.6), a quarter (26%) of the women were employed, and a quarter (27%) reported being married. The majority of women were Coloured (61%) or Black (36%). A total of 294 women were recruited from Coloured venues and 260 were recruited from Black venues. Compared to women from Black venues, women recruited from Coloured venues were on average older, were less educated, and more were married. In terms of HIV-related risk, a greater proportion of women in Black venues reported ever being tested for HIV, and a greater proportion of women in Black venues reported being HIV positive compared to women in Coloured venues.

Table 1.

Women in the longitudinal cohort: demographics and sexual risk at baseline overall and by venue race

| Total Sample (n=554) | Coloured Venues (n = 294) | Black Venues (n = 260) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t | |

| Sociodemographics | |||||||

| Age | 33.92 | 11.63 | 35.48 | 12.00 | 32.15 | 10.96 | 3.41*** |

| Education | 5.34 | 2.18 | 4.82 | 2.10 | 5.92 | 2.13 | −6.15*** |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 | |

|

|

|||||||

| Race | 263.49*** | ||||||

| Coloured | 340 | 61.4 | 272 | 92.5% | 68 | 26.2% | |

| Black | 201 | 36.3 | 16 | 5.4% | 185 | 71.2% | |

| White | 11 | 2.0 | 5 | 1.7% | 6 | 2.3% | |

| Indian | 2 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.4% | |

| Employed | 143 | 25.8 | 78 | 26.5% | 64 | 24.6% | 0.24 |

| Married | 150 | 27.1 | 102 | 34.7% | 48 | 18.5% | 18.41*** |

| Electricity | 536 | 96.8 | 287 | 97.6% | 249 | 95.8% | 1.50 |

| Tap Water | 496 | 89.5 | 260 | 88.4% | 236 | 90.8% | 0.80 |

| Refrigerator | 446 | 80.5 | 243 | 82.7% | 203 | 78.1% | 1.84 |

|

| |||||||

| HIV Risk | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Total number of sex partners in past 4 mo. | M= 1.41 | SD= 2.15 | M= 1.24 | SD= 1.95 | M= 1.60 | SD= 2.34 | t= −1.94† |

|

| |||||||

| Ever HIV tested | 453 | 81.8 | 229 | 78.9 | 224 | 86.2 | 6.32* |

|

| |||||||

| HIV positivea | 58 | 10.5 | 20 | 6.8 | 38 | 14.6 | 6.87** |

Notes:

t = t-test statistic;

p<.001, M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, N=cell size;

among those ever HIV tested;

Educated coded as 0 = no schooling, 1 = up to standard 1 or grade 3, 2 = standard 2–4 or grade 4–6, 3 = standard 5 or grade 7, 4 = standard 6 or grade 8, 5 = standard 7 or grade 9, 6 = standard 8 or grade 10, 7 = standard 9 or grade 11, 8 = standard 10 or grade 12, 9 = certificate or diploma with grade 12, 10 = Bachelor’s degree, and 11 = post graduate degree

Descriptive Characteristics of Men in the Venues

We surveyed male patrons from each of the 12 venues across the four time points to characterize the venues across time. Table 2 summarizes the venue characteristics overall and by venue race. Across the venues about half of the men surveyed reported coming to that bar at least weekly (54%). About 14% of the men reported coming to the bar to find a sex partner at the time they were surveyed. About one-quarter (23%) of the men reported ever meeting a sex partner at the bar, and of those men about one-quarter (24%) reported using a condom the last time they met a sex partner at the bar.

Table 2.

Men’s cross-sectional assessments: Venue-level characteristics overall and by race, and effects of venue adjusting for time

| All 12 Venues (n=48) | Coloured Venues (n=24) | Black Venues (n=24) | Venue Race Difference (n=48) | Venue Effect in Coloured Venues (n=24) | Venue Effect in Black Venues (n=24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t | F | F | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Average proportion of men | 0.54 (.16) | 0.45 (.15) | 0.64 (.11) | −4.74*** | 12.30*** | 1.61 |

| Men’s average education | 2.55 (.38) | 2.28 (.27) | 2.83 (.25) | −7.36*** | 2.90* | 17.49*** |

| Bar (Venue) Behaviors | ||||||

| Average proportion of men who came to bar at least weekly | 0.54 (.10) | 0.57 (.12) | 0.52 (.07) | 1.75† | 2.21† | 0.14 |

| Average proportion of men who came to find a sex partner | 0.14 (.06) | 0.13 (.05) | 0.16 (.06) | −1.88† | 0.33 | 2.52† |

| Average proportion of men who have ever met a new sex partner at the bar | 0.23 (.11) | 0.17 (.08) | 0.30 (0.09) | −5.43*** | 3.21* | 10.43*** |

| Average proportion of men who used a condom last time they met a new sex partner at the bar | 0.24 (.10) | 0.18 (.08) | 0.30 (.08) | −5.56*** | 0.54 | 4.59** |

| Average proportion of men who have ever had sex on bar premises | 0.07 (.04) | 0.06 (.04) | 0.08 (.03) | −1.24 | 1.53 | 0.90 |

| Alcohol Use | ||||||

| Men’s average alcohol consumption frequency | 3.27 (.25) | 3.32 (.29) | 3.22 (.20) | 1.44 | 5.03** | 1.53 |

| Men’s average alcohol consumption quantity | 3.79 (.35) | 3.86 (.35) | 3.72 (.23) | 1.68 | 5.74** | 0.93 |

| Men’s average frequency of binge drinking | 3.15 (.21) | 3.20 (.23) | 3.10 (.16) | 1.81† | 4.80** | 1.29 |

| Drug Use | ||||||

| Proportion of men who used marijuana past 4 mo. | 0.25 (.13) | 0.32 (.14) | 0.19 (0.07) | 4.33*** | 8.76*** | 5.11** |

| Proportion of men who used meth past 4 mo. | 0.09 (.08) | 0.14 (.08) | 0.04 (.03) | 5.26*** | 3.54* | 2.04 |

| Gender Attitudes | ||||||

| Average of sexist or traditional attitudes towards women | 2.68 (0.40) | 2.42 (.32) | 2.89 (.36) | −4.40*** | 4.23** | 4.59** |

| Sexual Risk Behavior | ||||||

| Men’s average number of sex partners past 4 mo. | 2.72 (1.41) | 2.31 (1.52) | 3.13 (1.19) | −2.06* | 1.05 | 3.99* |

| Men’s average number of sex acts past 4 mo. | 11.11 (5.13) | 11.55 (6.09) | 10.67 (4.05) | 0.59 | 1.03 | 0.61 |

| Men’s average number of unprotected sex acts past 4 mo. | 6.48 (4.87) | 8.03 (5.94) | 4.93 (2.87) | 2.31* | 0.91 | 1.42 |

| Men’s average proportion of unprotected sex past 4 mo. | 0.51 (.14) | 0.60 (.11) | 0.41 (.09) | 6.48*** | 0.32 | 3.73* |

| Average proportion of unprotected men past 4 mo. | 0.34 (.10) 0.34 (.10) |

0.40 (.10) | 0.28 (.06) | 4.86*** | 0.56 | 1.76 |

Notes: t= t-test statistic, F = F-test statistic;

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001;

M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation; The maximum n in these analyses is 48, which is a function of the 12 (6 Black and 6 Coloured) venues studied at 4 different time points; Education was coded as 1 = grade 7 or less, 2 = grade 8–11, 3 = grade 12, and 4 = beyond grade 12

As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences between Black and Coloured venues in male patron alcohol use. In terms of drug use, on average a quarter (25%) of men surveyed reported using marijuana in the past 4 months, and about 9% of men reported using meth in the past 4 months. Coloured venues had more men who recently used marijuana (32% vs. 19%) and meth (14% vs. 4%) compared to Black venues. For gender attitudes, Black venues (M = 2.89, SD = 0.36) had men who reported more sexist gender attitudes than Coloured venues (M = 2.42, SD = 0.32).

The average number of sex partners men reported in the previous 4 months was 2.72 (SD =1.41), with an average of about 11.1 (SD =5.13) sex acts, and 6.48 (SD =4.87) unprotected sex acts. Men’s average proportion of unprotected sex was 0.51 (SD =0.14). Including men who did not report recent sex, the average proportion of men reporting unprotected sex was 0.34. Although Black venues had men who reported more sex partners (M = 3.13, SD = 1.19 vs. M = 2.31, SD = 1.52), Coloured venues had significantly more sexual risk behavior in terms of male patrons’ lack of condom use. Specifically, men in Coloured venues reported a higher proportion of unprotected sex (M = 0.60, SD = 0.11 vs. 0.41, SD = 0.09).

Venue Effects

As preliminary tests to examine whether the twelve venues significantly differed from each other on the venue-level characteristics, we conducted ANOVA with time entered as a covariate. The columns on the right in Table 2 summarize the ANOVA results. Among both Coloured and Black venues, the venues significantly differed on several factors. Notably, whereas there were no differences among the Black venues in alcohol use, there were significant differences among the Coloured venues in alcohol consumption frequency (F = 5.03, p < .01) and quantity (F = 5.74, p < .01), and frequency of binge drinking (F = 4.80, p < .01). These tests allowed us to determine the variables that do not appear to systematically vary between venues in either Coloured or Black venues, and therefore could be eliminated as venue-level predictors of women’s unprotected sex in our multivariate models.

Multilevel Models

Before testing venue-level predictors of women’s unprotected sex, we examined the latter over time. In this model, time is entered as the sole predictor. Stratifying by race, we found that in Coloured venues women’s proportion of unprotected sex at initial assessment was 0.40, which was significantly different from zero (t=17.63, p <.001) and this did not change over time (B= −0.01, t = −0.98, 0.33). In Black venues women’s proportion of unprotected sex at initial assessment was 0.27, also significantly different from zero (t=13.92, p <.001), and this also did not change over time (B= 0.01, t = 1.19, 0.23).

Results for Coloured Venues

Table 3 summarizes results for the univariate multilevel models, which showed significant associations between unprotected sex among women in the prospective cohort and characteristics of men surveyed in their venues. In Coloured venues, women had a higher proportion of unprotected sex when they were recruited from venues with the following characteristics: greater proportion of men relative to women; men with higher education; more men who reported meeting a new sex partner at the bar; and men who reported lower sexist gender attitudes. The first two variables (proportion men and education) were very strongly related (r = .70, p < .001) and were also both strongly related to proportion meeting a new sex partner at the bar (r’s > .40, p’s < .01). Therefore we excluded proportion of men surveyed in the venues and men’s average education to avoid multicollinearity in the multivariate model.

Table 3.

Univariate multilevel model results predicting cohort women’s proportion of unprotected sex in the past 4 months, adjusting for time, stratified by venue race

| Coloured Venues (Level-1 n=1176, Level-2 n=294, Level-3 n=6) | Black Venues (Level-1 n=1040, Level-2 n=260, Level-3 n=6) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B | S.E. | t | B | S.E. | t | |

|

|

||||||

| Average proportion of men | 0.71 | 0.21 | 3.44* | −0.43 | 0.05 | −8.55*** |

| Men’s average education | 0.19 | 0.06 | 3.09* | −0.07 | 0.04 | −1.80 |

| Average proportion of men who have ever met a new sex partner at the bar | 0.42 | 0.07 | 5.69** | −0.16 | 0.10 | −1.67 |

| Average proportion of men who used a condom last time they met a new sex partner at the bar | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.97 | −0.26 | 0.07 | −3.71* |

| Men’s average alcohol consumption frequency | −0.07 | 0.06 | −1.18 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 5.32** |

| Men’s average alcohol consumption quantity | 0.12 | 0.04 | 2.71† | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Men’s average frequency of binge drinking | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.49 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 2.68† |

| Proportion of men who used marijuana past 4 mo. | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.86 | −0.27 | 0.16 | −1.71 |

| Proportion of men who used meth past 4 mo. | 0.51 | 0.35 | 1.44 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.64 |

| Average of sexist or traditional attitudes towards women | −0.91 | 0.26 | −3.56* | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.48 |

| Men’s average number of sex partners past 4 mo. | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.91 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.30 |

| Men’s average proportion of unprotected sex past 4 mo.a | −0.41 | 0.40 | −1.02 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 1.40 |

| Average proportion of unprotected men past 4 mo.b | −0.37 | 0.31 | −1.21 | −0.00 | 0.14 | −0.02 |

Notes:

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001;

B = unstandardized regression coefficient, S.E. = Standard Error, t = t-test statistic

computed among men who reported recent sex;

computed among all men, with men who did not report recent sex coded as 0% unprotected

Table 4 shows the results from the multivariate model for Coloured venues. In venues where there was a higher proportion of men ever meeting a new sex partner at the bar, women engaged in more unprotected sex (B = 0.35, p < .05).

Table 4.

Multivariate multilevel model results predicting cohort women’s proportion of unprotected sex in the past 4 months, adjusting for time: Coloured Venues (Level-1 n=1176, Level-2 n=294, Level-3 n=6)

| B | S.E. | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Average proportion of men who have ever met a new sex partner at the shebeen | 0.35 | 0.11 | 3.11* |

| Average of sexist or traditional attitudes towards women | −0.05 | 0.02 | −2.29 |

Notes:

p<.05;

B = unstandardized regression coefficient, S.E. = Standard Error, t = t-test statistic

Results for Black Venues

Models for women recruited from Black venues showed that women reported a higher proportion of unprotected sex when they were recruited from venues with the following characteristics (Table 3): a lower proportion of men relative to women; less men who reported using a condom the last time they met a sex partner at the bar; men who drank alcohol more frequently; and men had reported fewer protected sex acts. Proportion of men was strongly related to proportion using a condom last time they met a sex partner (r = 0.42, p < .01), and therefore we excluded the former from the multivariate model.

Table 5 shows results from the multivariate model for Black venues. In Black venues that had men who reported drinking more frequently, women reported a higher proportion of unprotected sex (B = 0.33, p < .01).

Table 5.

Multivariate multilevel model results predicting cohort women’s proportion of unprotected sex in the past 4 months, adjusting for time: Black Venues (Level-1 n=1040, Level-2 n=260, Level-3 n=6)

| B | S.E. | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Average proportion of men who used a condom last time they met a new sex partner at the shebeen | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.41 |

| Men’s average alcohol consumption frequency | 0.33 | 0.04 | 8.58** |

Notes:

p<.01;

B = unstandardized regression coefficient, S.E. = Standard Error

Discussion

Previous research has suggested that social and structural contexts are important in influencing HIV risk behavior. Research has also shown how alcohol-drinking venues in South Africa may be particularly risky places for women, especially to the extent that men in these venues engage in higher alcohol-related and sexual risk behavior. We systematically studied venue characteristics, operationalized as men’s drinking and sex behavior in the venues, as predictors of sexual risk behavior among women attending the same drinking venues in South Africa. We found that women’s unprotected sex was indeed associated with venue-level characteristics, namely the proportion of men who have met sex partners at the bar, and the amount of men’s drinking.

In contrast to previous research, our approach is novel in a number of ways. It is a well-known finding that alcohol use, or other individual-level characteristics, like HIV-related knowledge or condom use self-efficacy, are related to sexual risk behavior. The current study demonstrates that social contextual factors are also critical predictors of women’s risks for HIV. Guided by previous research, we conceptualized contextual factors of the venue as the attitudes and behaviors of their male patrons. Although we did not study physical or geographic aspects as other potential venue-level predictors of HIV-related risk, our focus on the social structural context is valuable and consistent with previous research and theory (Kincaid, 2004; Latkin, Hua, & Davey, 2004). As sex is inherently relational and alcohol use is heavily associated with social and sexual behaviors in South Africa, we systematically examined the role of venue-level predictors on individual-level risk behavior, and necessarily accounted for the nested data.

Consistent with data from nationally representative surveys in South Africa on race differences, we found that more women in Black venues (19.9%) reported being HIV positive than women in Coloured venues (6.8%), although women in Black venues were also more likely to report ever being tested for HIV. Whereas 93% of the women recruited in Coloured venues reported being Coloured, 71% of the women recruited in Black venues reported being Black, suggesting that the “Black venues” were more racially integrated than the Coloured venues. This may be a feature of the township in which we conducted the current research, in that generally speaking the Black areas may be more integrated than Coloured areas.

Our study used a prospective design, allowing us to understand whether women’s sexual risk behavior changed through time. Our findings indicated that the women’s proportion of unprotected sex remained stable throughout the course of a year. Women’s unprotected sex was associated with venue-level characteristics, namely the behavior of men in the bars. Yet, the direction of this relationship is potentially bidirectional. Specifically, women’s risk behavior is influenced by social structural factors of these male dominated drinking venues. When women attend alcohol-drinking venues where men engage in higher alcohol and sexual risk behavior, their own sexual risk behavior may increase. It may also be the case that women who engage in risky sexual behavior prefer to attend venues where the men are also more risky. In either case, higher risk behaviors among women are occurring in venues dominated by men who drink more heavily and meet sex partners at the venue, suggesting the need to target multiple levels that encompass women, men, and their social interactions as venue factors in HIV interventions.

Findings from the current study should be viewed in light of their limitations. Results are limited to men and women attending shebeens in one South African township and my not generalize to other areas in South Africa. Findings related to substance use and sex behaviors are likely to vary between people who do and do not attend shebeens, suggesting that these findings should not be extended to non-drinking social venues. Participants with partners were not linked in the study, which precludes us from the ability to draw dyadic level conclusions with the current data. Other venues, such as shacks, community halls, salons, and night clubs, have also been documented as places where men and women go to meet sex partners and therefore understanding reasons for choosing these venues may offer important information for understanding disease transmission patterns. Although our study used a prospective design, the findings are correlational and thus we are unable to make causal inferences about the significant associations. Given the correlational design, the inclusion of established confounders of the association between men’s attitudes and behaviors with women’s sexual risk behavior in the multivariate models would help rule out alternative explanations. Unfortunately, given that this study is the first of its kind (e.g., to test men’s alcohol use on women’s unprotected sex) no known confounders exist. We therefore relied on associations in available data to identify potential covariates. Future research with a larger sample and more statistical power may be interested in examining the role of other variables that might relate to both men’s drinking behaviors and women’s sexual risk, namely individual alcohol expectancies and intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization. Both sets of variables have been shown to relate to sexual risk behavior among female patrons in drinking settings in South Africa (Pitpitan et al., 2012). Finally, we relied on self-report to measure socially sensitive behaviors. Although we used anonymous and confidential data collection strategies and undertook every effort to increase candid responding, our data nevertheless likely represent lower-bound estimates of substance use and sexual behaviors. With these limitations in mind, our findings have important implications for HIV prevention with women and men in South African drinking venues.

Among women attending drinking venues in South Africa, it will be necessary to design interventions that target venue characteristics to support and sustain women’s sexual risk reduction efforts (Kincaid, 2004) However, there have been few studies of sexual risk reduction programs for women in drinking venues. One multilevel intervention that targeted women sex workers in bars, discos, and night clubs in the Philippines demonstrated promising outcomes (Morisky, Stein, Chiao, Ksobiech, & Malow, 2006). This intervention incorporated peer counseling to deliver HIV risk education, condom use skills, and sexual communication strategies. At a second level, the intervention enlisted the managers of the drinking places to attend trainings to implement a continuum of HIV prevention policies and practices in their venues. Results showed that the combination of peer counseling and manager training demonstrated significant reductions in subsequent STI over the observation period compared to venues that delivered only a single intervention. Research is needed to test whether multilevel interventions can change the social environment of drinking venues in South Africa, particularly the attitudes and behaviors of men in the venues, as a means of protecting women from HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01AA018074 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health. Preparation of this manuscript was supported by grant K01DA036447 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics.

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All individual participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. Institutional review boards at participating institutions approved all consent and study procedures. This study was supported by grant R01AA018074 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Cain D, Pare V, Kalichman SC, Harel O, Mthembu J, Carey MP, … Mwaba K. HIV risks associated with patronizing alcohol serving establishments in South African Townships, Cape Town. Prevention Science. 2012;13(6):627–634. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0290-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher AJ. Urban Segregation in Post-apartheid South Africa. Urban Studies. 2001;38(3):449–466. [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. American Psychologist. 1991 doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK. How Integrative Behavioral Theory Can Improve Health Promotion and Disease Prevention 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK. Changing our unhealthy ways: Emerging perspectives from Social Action Theory. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. 2009;2:359–389. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L, Walker L. Treading the path of least resistance: HIV/AIDS and social inequalities—a South African case study. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;54(7):1093–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble JN, Miller HG, Rogers SM, Turner CF. Interview mode and measurement of sexual behaviors: Methodological issues. The Journal of Sex Research. 1999 doi: 10.1080/00224499909551963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Sciences Research Council. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Cherry C, Jooste S, Mathiti V. Gender attitudes, sexual violence, and HIV/AIDS risks among men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(4):299–305. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research. 2007;8(2):141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Jooste S, Cain D. HIV/AIDS risks among men and women who drink at informal alcohol serving establishments (Shebeens) in Cape Town, South Africa. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research. 2008;9(1):55–62. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Buyze J, Colebunders R. HIV Prevalence by Race Co-Varies Closely with Concurrency and Number of Sex Partners in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINCAID DL. From Innovation to Social Norm: Bounded Normative Influence. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9(sup1):37–57. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Hua W, Davey MA. Factors Associated with Peer HIV Prevention Outreach in Drug-Using Communities. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(6):499–508. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.6.499.53794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Stein JA, Chiao C, Ksobiech K, Malow R. Impact of a social influence intervention on condom use and sexually transmitted infections among establishment-based female sex workers in the Philippines: A multilevel analysis. Health Psychology. 2006;25(5):595–603. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Johnson ME. HIV Risk Behavior Self-Report Reliability at Different Recall Periods. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):152–161. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CDH, Plüddemann A, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R. Alcohol use in South Africa: findings from the first Demographic and Health Survey (1998) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(1):91–97. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Cain D, Sikkema KJ, Skinner D, Pieterse D. Gender-based violence, alcohol use, and sexual risk among female patrons of drinking venues in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9423-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. Sage Publications Incorporated; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Addiction (Abingdon, England) 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, Carey KB, Cain D, Harel O, Mehlomakulu V, … Kalichman SC. Patterns of alcohol use and sexual behaviors among current drinkers in Cape Town, South Africa. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(4):492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend L, Ragnarsson A, Mathews C, Johnston LG, Ekström AM, Thorson A, Chopra M. “Taking care of business”: alcohol as currency in transactional sexual relationships among players in Cape Town, South Africa. Qualitative Health Research. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1049732310378296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredoux CG, Dixon JA. Mapping the Multiple Contexts of Racial Isolation: The Case of Long Street, Cape Town. Urban Studies. 2009;46(4):761–777. [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Sonenstein FL, Pleck JH. Impact of ACASI on reporting of male-male sexual contacts: Preliminary results from the 1995 National Survey of Adolescent Males. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. 1996:171. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. n.d:364. [Google Scholar]

- Watt MH, Aunon FM, Skinner D, Sikkema KJ, Kalichman SC, Pieterse D. “Because he has bought for her, he wants to sleep with her”: Alcohol as a currency for sexual exchange in South African drinking venues. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Morroni C, Coetzee N, Spencer J, Boerma JT. A pilot study of a rapid assessment method to identify places for AIDS prevention in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(Suppl 1):i106–113. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]