Abstract

Objective

Performance monitoring deficits have been proposed as a cognitive marker involved in the development of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but it is unclear whether these deficits cause impairment when established action sequences conflict with environmental demands. The current study applies a novel data-analytic technique to a well-established sequence learning paradigm to investigate reactions to disruption of learned behavior in ADHD.

Method

Children (ages 8–12) with and without ADHD completed a serial reaction time task in which they implicitly learned an 8-item sequence of keypresses over the course of 5 training blocks. The training sequence was replaced with a novel sequence in a transfer block, and returned in two subsequent recovery blocks. Response time data were fit by a Bayesian hierarchical version of the linear ballistic accumulator model which permitted the dissociation of learning processes from performance monitoring effects on RT.

Results

Sequence-specific learning on the task was reflected in the systematic reduction of the amount of evidence required to initiate a response, and was unimpaired in ADHD. When the novel sequence onset, typically-developing children displayed a shift in their attentional state while children with ADHD did not, leading to worse subsequent performance compared to controls.

Conclusions

Children with ADHD are not impaired in learning novel action sequences, but display difficulty monitoring their implementation and engaging top-down control when they become inadequate. These results support theories of ADHD that highlight the interactions between monitoring processes and changing cognitive demands as the cause of self-regulation and information-processing problems in the disorder.

Keywords: ADHD, serial reaction time, motor learning, evidence accumulation model, performance monitoring

The capacity to learn a complex sequence of motor responses allows for the automatization of myriad everyday processes. Activities that initially require intensive attentional resources, from handwriting, to playing piano, to riding a bike, can eventually be implemented with minimal awareness or cognitive effort. Yet, even after a task has been mastered, optimal performance requires ongoing monitoring of the action sequence (Botvinick et al., 2001) and an ability to dynamically modify it when conflicts arise (Ridderinkhof, Forstmann, Wylie, Burle & van den Wildenberg, 2011: Ridderinkhof, van den Wildenberg, Segalowitz & Carter, 2004).

Influential theoretical models of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (e.g. Albrecht et al., 2008; Barkley, 1997; Sergeant, 2000, 2005; Shiels & Hawk, 2010) have suggested that performance monitoring, a neurocognitive process implemented by the anterior cingulate cortex which alerts cognitive control systems to conflicts between action sequences and goals (Botvinick et al., 1999; 2004; van Veen and Carter, 2002), is an important cognitive mechanism involved in the development of the disorder. Supporting this view, children with ADHD show impairments in their ability to utilize feedback in the context of structured learning paradigms (Huang-Pollock, Maddox & Tam 2014), do not slow down after committing an error (Balogh & Czobor, 2014; Schachar et al., 2004; Sergeant & van der Meere, 1988; Shiels, Tamm & Epstein, 2012; Wiersema et al., 2005), show reduced event-related potential (ERP) responses to auditory conflict during a Stroop paradigm (van Mourik et al., 2011), and show lower error-related negativity, an ERP signature associated with the detection of errors and conflict monitoring processes (Geburek et al., 2013; Groen et al., 2008; Liotti, Pliszka, Perez, Kothmann, & Woldorff, 2005; van Meel, Heslenfeld, Oosterlaan, & Sergeant, 2007; Albrecht et al., 2008). At the same time, a number of studies have also found evidence for either intact or better performance monitoring among children with ADHD, both within the ERP (Burgio-Murphy et al., 2007; Jonkman et al., 2007; Wiersema et al., 2005) and post-error slowing literatures (Jonkman et al., 2007; van Meel et al., 2007). Thus, although evidence exists for such a deficit, this evidence is not consistent.

A more fundamental issue is that the rules and contingencies for performance on tasks typically used in this literature (e.g. go-no-go and stop signal reaction time tasks; Shiels & Hawk, 2010) tend to remain constant throughout the course of the task. In contrast, on a day to day basis, performance monitoring is most critical when complex action sequences must be learned and changed when environmental contingencies require adaptation. Indeed, Nigg and Casey (2005), in their discussion of implicit learning and ADHD, point out that many behavioral problems children with ADHD face could be attributed to a failure to adapt their behavior to rapidly shifting environmental demands. Thus, a significant limitation of the prior literature is that conflict and performance monitoring in ADHD has not been assessed in situations where children must use feedback to improve or tailor their behavior to suit rapidly changing environmental demands.

In the current study, we examine the implicit learning and monitoring of complex motor sequences in children with ADHD using as motor sequence learning paradigm, the Serial Reaction Time (SRT) task (Nissen & Bullemer, 1987). In this paradigm, participants are presented with a stimulus within one of four boxes aligned horizontally on a computer screen and indicate its location by pressing the corresponding button on a four-choice response box. Unbeknownst to participants, the stimuli appear in a regular spatial sequence throughout several blocks of a “training phase” (Schwarb & Schumaker, 2012). Good performance on the SRT task therefore requires participants to learn the sequence of presented visual stimuli, to select the appropriate response key, and to program the muscle movements to make the response (Howard et al., 1992; Mayr, 1996: Willingham, 1999). Response time (RT) improvements seen throughout the training blocks are due to general practice effects associated with increased familiarity with the task, as well as to sequence specific learning effects (Janacsek & Nemeth, 2013). In sequence specific learning, implicit associations develop between trial n and n+1, such that trial n eventually comes to serve as a predictive cue for the identity of the subsequent target, leading to earlier response initiation (Nixon & Passingham, 2001). Although there is some debate about whether a pure dissociation between explicit/effortful and implicit/automatic processes in learning is possible (Shanks, 2010), participants typically cannot produce the sequence on their own following the task, suggesting that sequence-specific learning on the task is implicit (Robertson, 2007; Schwarb & Schumaker, 2012).

Motor skill learning on the SRT is supported by neural circuitry that includes the motor cortical areas, the subcortical striatum, and cerebellum (Keele et al., 2003; Robertson, 2007). In a manner consistent with behavioral observations of performance, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) studies have demonstrated that during the initial stages of motor sequence learning, when attentional demands are greatest, areas involved in planning and cognitive control, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and premotor regions, are activated (Jueptner et al., 1997; Keele et al., 2003; Lohse et al., 2014; Poldrack et al., 2005). However, as the motor sequence becomes established and overlearned, explicit attentional demands decrease, as indexed by reduced activation in these areas (Jueptner et al., 1997; Keele et al., 2003; Poldrack et al., 2005). Concurrent increases are seen in a sensorimotor network (composed of the supplementary and primary motor cortex), areas which are responsible for movement control and the implementation of motor sequences (Jueptner et al., 1997; Lohse et al., 2014). Thus, as the sequence becomes increasingly automatic, areas of the brain responsible for performance shift from those that support effortful, attention-demanding task performance to those which support an automatic motoric representation of the sequence.

Most important to the goal of assessing how children with ADHD respond to changes in their environment, however, is the introduction of a “transfer” block. In this block, an alternate or random sequence is presented without the participants’ knowledge. The strength of the sequence specific learning effect has typically been measured by taking a difference in mean RT (MRT) between the last training block and the transfer block. In the current study, the transfer block provides a unique opportunity to observe what happens when a learned behavior suddenly conflicts with environmental demands; because the learned sequence differs from the novel sequence, an attention-demanding conflict occurs. Indeed, negative ERP responses to SRT stimuli that deviate from the learned sequence are similar to those elicited by errors (Eimer, Goschke, Schlaghecken & Sturmer, 1996; Ferdinand, Mecklinger & Kray, 2008), suggesting that the onset of an unlearned sequence is processed similarly to other conflicts between actions and task demands. Thus, when participants enter the transfer block, conflict monitoring processes must alert other nodes in the action control network (Ridderinkhof et al., 2004) to weight a strategy that emphasizes the allocation of focused attention to the task once again.

Because children with ADHD have difficulty acquiring skilled performance and automaticity for complex cognitive processes (Huang-Pollock & Karalunas, 2010; Huang-Pollock, Maddox & Tam 2014), impaired initial acquisition of a complex motor sequence during training, particularly in light of well-known fine motor deficits in that population (Pitcher, Piek, & Hay, 2003; Rommelse et al., 2009) would not be unexpected. However, several previous studies have found no abnormalities in SRT performance or in reactions to conflict on the transfer block, as indexed by mean RTs, in this population (Karatekin et al., 2009; Laasonen et al., 2014; Vloet et al., 2010; but see Barnes et al., 20101). This is likely in part because the standard performance measure used in SRT is MRT.

Dependence on MRT alone is problematic because RT is made up of multiple component processes, including the speed of the perceptual decision process, stimulus encoding, speed-accuracy trade-off effects, and the initiation and coordination of the motor response (Ratcliff & McKoon, 2008). Examination of MRT alone may obscure the presence of true group effects if these separate coordinating processes have opposite effects on RT, or may lead to incorrect conclusions about group differences if assumptions about the cause of RT differences are incorrect. For example, although longer RTs in older adults have long been assumed to reflect slower information processing with age, studies using novel data-analytic techniques revealed that these slowdowns are, instead, largely due to more cautious responding in older adults (Ratcliff, Thapar, Gomez & McKoon, 2004; Ratcliff, Thapar, & McKoon, 2011; 2001; Ratcliff, Thapar & McKoon, 2003). Thus, linking poor conflict monitoring to deficits in performance is contingent upon being able to isolate the specific sub-process that is adjusted when conflict is detected, making MRT a poor measure for this task.

Recent progress in the development and implementation of formal models for choice RT has allowed researchers to tease apart these processes. These “evidence accumulation” models, which frame simple decisions as a race between information accumulated in favor of each choice, have been extraordinarily successful at accounting for the shape and properties of human choice RT distributions (Smith & Ratcliff, 2004). Two such models, the Ratcliff drift diffusion model (DDM: Ratcliff, 1978; Ratcliff & McKoon, 2008) and the linear ballistic accumulator (LBA: Brown & Heathcote, 2008), have been applied to explore the impact of variables as diverse as aging (Ratcliff, Thapar, & McKoon, 2011), early development (Ratcliff, Love, Thompson & Opfer, 2012), adolescent depression (Ho et al., 2014) and childhood ADHD (Huang-Pollock, Karalunas, Tam & Moore, 2012; Karalunas, Huang-Pollock & Nigg, 2012; Karalunas & Huang-Pollock, 2013; Weigard & Huang-Pollock, 2014) on components that make up RT. Recently-developed hierarchical Bayesian versions of both models (Turner, Sederberg, Brown & Steyvers, 2013; Wiecki, Sofer & Frank, 2013) increase statistical power and stability of parameter estimates by the simultaneous estimation of individual and group mean parameters, while also allowing for Bayesian hypothesis testing.

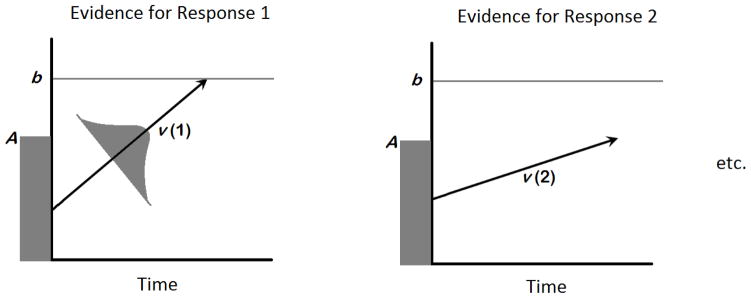

Although the LBA and DDM tend to produce similar estimates of psychologically meaningful parameters when applied to the same dataset (Donkin, Brown, Heathcote & Wagenmakers, 2011) a unique and instrumental feature of the LBA is its ability to be applied to multiple choice tasks (Brown & Heathcote, 2008). This feature makes the LBA, but not DDM, amenable to modeling the SRT task. The LBA frames decisions as a race between two or more information accumulators (Figure 1), each of which corresponds to a possible response, towards a response boundary that, when reached, allows the “winning” response to be initiated (Brown & Heathcote, 2008). The average speed of evidence accumulation in favor of each response is reflected in the model parameter drift rate (v). While this speed is determined by individual ability and the quality of the stimulus itself, it can also be determined by an individual’s level of arousal or attentional state (Ho et al., 2012; Karalunas, Geurts, Konrad, Bender & Nigg, 2014; Kelly & O’Connell, 2013; Rae, Heathcote, Donkin, Averall & Brown, 2014; Smith, Ratcliff & Wolfgang, 2004). The amount of perceptual evidence an individual requires to initiate a motor response is reflected by the response boundary (b) parameter. The model parameter of nondecision time (t0) accounts for the amount of time in an RT that is taken up by processes other than accumulating evidence for the decision. This includes the time it takes low-level perceptual processes to encode the stimuli, as well as the time it takes for an individual to execute the motor response. Modulating each of these parameters affects behavioral performance in distinct ways, and this allows the parameters’ distinct contributions to be estimated from behavioral data. All other parameters remaining equal, reducing v leads to slower and more variable RTs and decreased accuracy rates. Reducing b speeds RT, but at the cost of increasing error rates. Reducing t0 speeds RT, but does not affect accuracy or the variance of the RT distributions.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Linear Ballistic Accumulator model (Brown & Heathcote, 2008); Evidence for each response accumulates separately until one “winning” accumulator terminates at the response boundary (b). The start point of each accumulator for a given trial is sampled from a uniform distribution bounded at 0 and A, and the rate of evidence accumulation for that trial is sampled from a normal distribution with a mean of v.

With these parameters in mind, we would therefore expect that in an SRT task, the learned associations between trial n and n+1 would lead to earlier response initiation of the n+1 keypress, and that this would be reflected in the boundary separation parameter. Decreases in boundary separation would be seen throughout the training trials, would increase during the transfer block (because the benefits of that learning disappear), and would decrease again on recovery. An unpublished investigation of the SRT task in typical young adults with the LBA model did, in fact, find that RT changes could almost entirely be attributed to changes in the boundary parameter (Marshall & Visser, in preparation) supporting the latter possibility. If children with ADHD demonstrate deficits in learning the motor sequence, then a group x block interaction on the boundary parameter during training trials would be expected.

With respect to drift rate, we might reasonably expect that as the motor sequence becomes overlearned and explicit attentional demands decrease, drift rate, as an index of attentional engagement, would decrease over training blocks. Subsequent increases in drift would be expected on the transfer block after the conflict between the learned and transfer sequences is detected. If children with ADHD are impaired in their performance monitoring of learned action sequences, they would be expected to display a smaller increase in drift rate on the transfer block relative to their typically developing peers, and worse subsequent task performance. It is this reaction to the perturbation of the transfer block and performance following this block that we are most interested in understanding.

With respect to t0, previous studies have found that “task general” improvements in motor coordination based on simple familiarization with the task (as opposed to sequence specific) show up as reductions in t0 (e.g., Dutilh et al., 2009, 2011; Weigard & Huang-Pollock, 2014). Because these improvements are not sequence specific, t0 would not be expected to display transfer or recovery effects. To the extent that children with ADHD have deficits in fine motor coordination (Pitcher, Piek, & Hay, 2003; Rommelse et al., 2009), slower t0 overall would be expected.

In summary, the application of the LBA model to data from the SRT task provides a perfect opportunity to simultaneously examine the learning of novel action sequences and how performance monitoring of these sequences contributes to the adaptation of behavior to changing environmental demands. By breaking performance down into its specific constituents, the LBA allows for better characterization of these effects in typically-developing children, and thus can help pinpoint exactly where these processes may break down in ADHD. Given the previous research outlined above, we predict:

In both groups, reductions in boundary will explain the sequence-specific learning effect in RT. That is, boundary will decrease over the training phase, increase on the transfer block, and decrease again in the recovery phase, and consistent with the majority of the prior research on the SRT task in ADHD populations, there will be no group differences in learning effects as indexed by the boundary parameter, indicating intact motor sequence learning in the disorder.

As the task becomes overlearned, and attentional demands decrease, drift rate is expected to decrease. Drift rate is expected to increase on the transfer block after detection of the conflict between the learned and novel sequences. Due to inadequate performance monitoring, children with ADHD will display a diminished or absent increase in drift rate on the transfer block, and worse subsequent performance.

As t0 is expected to index improvements in task-general, but not sequence-specific, processes, this parameter is expected to show reductions during the training phase, but not to show transfer or recovery effects. Given prior research showing weak or no effects of ADHD on this parameter, group differences in t0 are not expected.

Methods

Participants

Children ages 8–12, with (N=66; 36 male) and without (N=66; 31 male) ADHD were recruited from local schools, newspaper ads, radio ads, and distributed flyers in the Centre and Dauphin county areas of Pennsylvania. The sample ethnicity was as follows (reflecting demographics of the region): 71.2% Caucasian/non-Hispanic, 3.8% Caucasian/Hispanic, 1.5% other Hispanic, 9.8% African American, 2.3% Asian, 7.6% mixed and 3.8% unknown/missing. Exclusion criteria included (a) current non-stimulant medication treatment, (b) pervasive developmental disorder, intellectual or sensorimotor disability, psychosis, or other parent-reported neurological disorder, and (c) estimated Full Scale IQ (FSIQ)≤80 based on a 2-subtest short-form (vocabulary and matrix reasoning, test-retest reliability=0.93, predictive validity=0.87) of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for (WISC-IV: Wechsler, 2003). The presence of anxiety, depression, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder was not exclusionary in either group.

Children with ADHD

Children identified as having ADHD met DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994) for ADHD including age of onset, duration, cross situational severity, and impairment as determined by parental report on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-IV (DISC-IV) (Shaffer, Fisher, & Lucas, 1997). At least one parent and one teacher report of behavior on the Attention, Hyperactivity, or ADHD subscales of the Behavioral Assessment Scale for Children (BASC-2: Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) or the Conners’ Rating Scales (Conners’: Conners, 2001) was required to exceed the 93rd percentile (T-score>65). Following DSM-IV field trials (Lahey et al., 1994), an “or” algorithm integrating parent report on the DISC and teacher report on the ADHD Rating-Scale (DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulos, & Reid, 1998) was used to determine symptom count and subtype (see Table 1). Children prescribed psychostimulant medication (N=18, 27%) were asked to discontinue medication use for 24–48 hours prior to the study (mean washout time =50 hours, median=41 hours).

Table 1.

Description of groups. Means, with standard deviation in parentheses. All ratings scales reported in T-scores unless otherwise noted.

| Control | ADHD | |

|---|---|---|

| N(Males:Females) | 66(36:30) | 66(39:33) |

| #Subtypes (H,I,C) | 5,24,37 | |

| Age | 10.18(1.31) | 9.96(1.21) |

| Estimated FSIQ | 107.95(10.66) | 104.86(12.16) |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | ||

| Total # of symptoms | 0.30(.63) | 6.06(3.01)*** |

| Parent BASC-2 | 43.69(5.89) | 66.00(13.04)*** |

| Parent Conners | 46.24(2.87) | 68.60(13.62)*** |

| Teacher BASC-2 | 43.71(4.17) | 64.28(13.36)*** |

| Teacher Conners | 45.68(2.85) | 63.95(12.31)*** |

| Inattention | ||

| Total # of symptoms | 0.83(1.24) | 7.97(1.47)*** |

| Parent BASC-2 | 44.39(5.67) | 67.00(5.31)*** |

| Parent Conners | 46.00(3.84) | 72.80(11.18)*** |

| Teacher BASC-2 | 43.71(5.68) | 63.65(6.39)*** |

| Teacher Conners | 46.14 (4.33) | 61.56(12.08)*** |

| Comorbidity (DISC: past year) | ||

| MDD | 0 | 1 |

| GAD | 1 | 6 |

| ODD/CD | 1/0 | 28/9 |

p<.05,

p<.001, H = primarily hyperactive subtype, I = primarily inattentive subtype, C = Combined subtype

Non-ADHD Controls

Controls did not meet criteria for ADHD on the DISC-IV, had T-scores below the 80th percentile (T-score≤58) on all listed rating scales, had ≤ 2 inattentive symptoms and ≤ 2 hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, and < 3 total symptoms combined between parent “or” teacher report. They had never been previously diagnosed or treated for ADHD. To equate IQ levels between groups, controls with IQs ≥ 130 were excluded.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics. Comparisons of symptom counts indicated that children with ADHD displayed more inattentive, t(130)=−31.3, p<.001, and hyperactive/ impulsive, t(130)= −14.37, p<.001, symptoms than controls. There were no statistically significant group differences in FSIQ, t(130)=1.56, p=.12, or age, t(130)=.977, p=.33.

Procedures

The experimental task was completed as part of a larger battery of experimental and standardized measures that took place over two three-hour sessions on separate days. All data were collected in compliance with human subjects’ approval from the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board (IRB#32126). Informed written consent from parents and verbal assent from children were obtained prior to participation. Children received a small prize for participation while parents received monetary compensation and informal clinical feedback.

Serial Reaction Time Paradigm

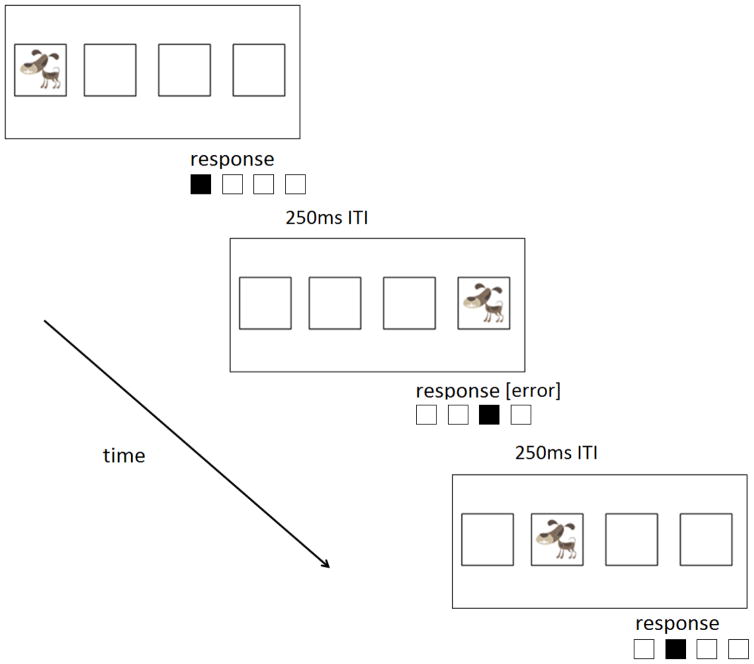

The experimental paradigm followed standard, well-accepted methodological guidelines for implementation of a SRT task. On each trial, an image of a dog was presented in one of four locations aligned horizontally in the middle of a computer monitor (Figure 2). Children were asked to catch the dog by pressing one of four keys on a serial response box that corresponded to the dog’s location. The next stimulus location appeared 250 ms after the child’s response. An auditory tone followed any incorrect response. Children were trained on one of two 8-item training sequences (S1: 34231241 or S2: 43142132, with 1 being the leftmost key). Children were not told that an underlying predictable sequence was present, and each block of trials during the training period started at a different point in the sequence to hide the fact that a repeating structure was present. Both sequences were composed entirely of second order conditionals (in which the target location can only be determined by the previous two, rather than previous one, location), were matched in terms of location, transition, reversal, rate of full coverage, and rate of transition usage (Reed & Johnson, 1994), and neither contained runs of items of length greater than two (e.g. 123 or 4321).

Figure 2.

Example stimulus moving in 3 steps of a sequence. “ITI” represents the interstimulus interval between each trial.

Children completed 5 blocks of training trials (each block contained 20 repetitions of the 8-item sequence), followed by a transfer block in which a novel sequence was presented, and ending with two blocks of the original sequence. Children were not informed of the sequence switches. Half of the children in each diagnostic group were presented with S1 during training blocks 1–5, and recovery blocks 7–8. During the transfer block 6, those children were presented with S2. The other half of the children were presented the reverse: S2 on blocks 1–5, and 7–8, with S1 on block 6. There were no main effects of sequence on RT or accuracy (both p>0.09, both η2<.0.02), no sequence x block interactions (both p>0.57, both η2<. 0.01), and there were no significant two or three way interactions with ADHD status (all p>.23, all η2<. 02). Training sequences were therefore collapsed for analyses.

Linear Ballistic Accumulator Model Analysis

Response times (RT) for correct and error trials <300ms and >5000ms (<4% of trials in each group) were excluded to eliminate fast guesses and outliers (Luce, 1986; Ratcliff & Tuerlinckx, 2002). Remaining trials were formatted in seconds and fit to an LBA model for a 4-choice task. As described by Turner, Sederberg, Brown and Steyvers (2013), the Bayesian hierarchical version of the LBA allows for the sampling from posterior distributions of the mean parameter values for each group in an analysis, as well as parameter estimates for all individuals in the groups that are informed by these group-level distributions. This method uses Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations to obtain posteriors for group level parameter values, which were truncated normal distributions defined by two hyper-parameters, a mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ), based on RTs from all participants within the group. Broad and relatively uninformative priors are posited for these parameters. The prior distributions assigned for the μ parameters were also truncated normal distributions, defined by two fixed prior parameters (another μ and σ). The prior distributions for the group-level σ parameters are gamma distributions, defined by two fixed prior parameters (a shape, and rate). Posterior distributions of true parameter values for each individual (θ) are then estimated using the group level posterior distributions as prior distributions, and thus only sampling values for individuals that are plausible given the group-level fits (i.e., “shrinkage”). Because the method increases the accuracy of parameter estimates by pooling the RTs of many participants, it is optimal for situations in which there are few trials at the individual level, or small RT distributions for one condition or type of response at this level (e.g., low error rates).

Fitting Procedure

Parameters of the LBA are often correlated, which can be highly problematic when using MCMC simulations because proposed moves for the Markov chains, which generally come from an uncorrelated Gaussian distribution, may be far from the target distribution, leading to high rejection rates and inefficient sampling. The differential evolution (DE-MCMC; Turner et al., 2013) method addresses this issue by generating proposals for a given Markov chain that are the difference between the current state of two other chains, chosen at random, rather than using an uncorrelated Gaussian kernel. The proposals generated from this method have been demonstrated to have rejection rates that are not affected by correlations between model parameters (Turner et al., 2013).

DE-MCMC simulations to improve sampling efficiency were implemented in R (R Core Team, 2013) to obtain group-level and individual level posterior distributions of the following parameter values for each block: drift rate to correct responses (vc), drift rate to errors (ve), response boundary settings (b), and non-decision time (t0). The starting point distribution (A) and variability in drift rate to errors (sv.e) parameters were also estimated, though assumed to be fixed between blocks, while the variability in drift to correct (sv.c) was fixed at 1 as a scaling parameter (Donkin, Brown & Heathcote, 2009). A “contaminant mixture” assumption (Ratcliff & Tuerlinckx, 2002) that 5% of trials were not related to the decision process, but contaminating RTs, uniformly distributed across the RT distributions, was also applied to stabilize estimates of t0 and b. Group and individual-level parameters were each estimated using 50 sampling chains. A burn-in period of 4400 iterations per chain was necessary for the chains to converge on stable distributions. Following this period, 800 iterations of the simulation were used to obtain posterior distributions of 40,000 samples for each parameter. Means of the individual posteriors were used to estimate individual parameter values.

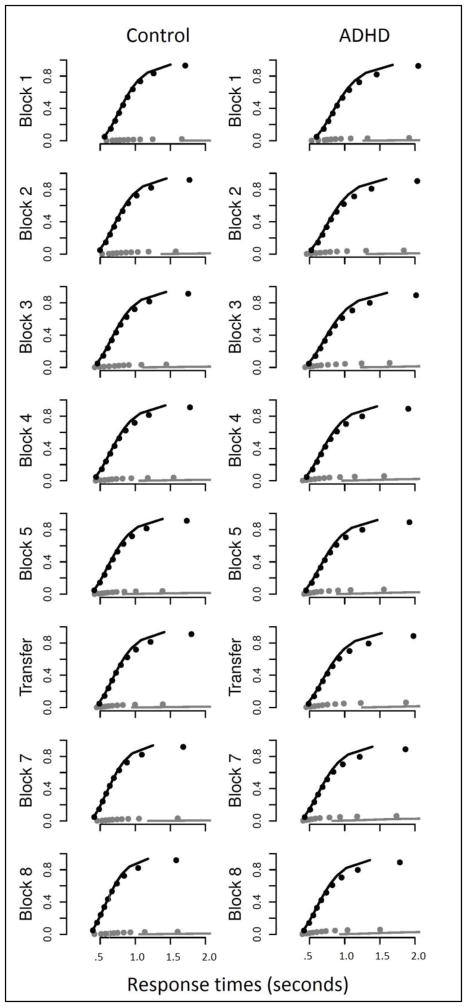

Model Fit

Model fit was investigated by inspection of plots comparing the predicted and actual data. Figure 3 displays plots comparing predicted and actual response time quantiles for the group-level parameters. Model fits to the correct response times were highly accurate, while fits to error RTs were poor in comparison. This was due to the low number of error trials relative to correct trials which caused the likelihood function to be influenced to a much greater degree by how well the correct trials, rather than error trial were described by the model parameters. Because of this, all model parameter estimates were considered valid except for drift rates for the error accumulators and their standard deviations, which were not further analyzed.

Figure 3.

Plots of actual response time quantiles (dots) compared with those predicted by fitted model parameters (lines) for group-level fits. Black = correct, Gray = errors

Data Analysis Plan and Hypothesis Testing

Effects for MRT and accuracy were evaluated using traditional null hypothesis significance testing (NHST) analyses (repeated-measures ANOVAs). However, the generation of posterior distributions for the group-level estimates (μ) of the mean parameter values in each group allowed us to conduct Bayesian hypothesis testing on the LBA parameters of interest. Because the individual parameter values from the hierarchical model violate the assumption of independence, these data are inappropriate for NHST analyses. Therefore, Bayesian inference was used as the primary analysis method for this data. Although Bayesian and NHST analyses on the parameter data converged for the most part, we note any minor discrepancies between these two modes of inference in footnotes below.

Bayesian inference was conducted using odds ratios (OR) calculated from the group posterior distributions for the parameter values. Random samples were drawn exhaustively from these distributions and instances in which the value for a distribution exceeded that from the comparison distribution, and vice versa, were counted. Following this, the larger count was divided by the smaller count to yield a ratio, relative to 1, of the likelihood that the true distributions are different. For example, an OR of 12:1 indicates that there is a 12 to 1 chance that true means within the population are different, while an OR of 2:1 is, in contrast, very ambiguous evidence for a difference (Kass & Raftery, 1995; Wagenmakers et al., 2014). For the current study, a cutoff of 3:1, as recommended by Kass & Raftery (1995), was adopted for determining whether there was sufficient positive evidence for a given effect. While traditional NHST analyses evaluate whether the data are unlikely under the null hypothesis, Bayesian inference provides an indication of whether the hypothesized difference actually exists and allows readers to judge the likelihood of the effect based both on the degree of evidence provided and prior likelihood (Wagenmakers et al., 2014).

Three types of within-subjects effects were investigated: Training effects (blocks 1–5), Transfer effects (blocks 5–6) and Recovery effects (blocks 6–8). While NHST analyses used repeated-measures ANOVAs which included data from all blocks in each effect, Bayesian analyses were only concerned with whether there was a net effect in each phase (e.g., block 5 being lower than block 1 in the training phase) rather than parametric effects at each step (block 2 is less than block 1 and block 3 is less than block 2, etc.). Thus, ORs for differences in the mean (μ) of the parameters were tested in the following way; the Training effects test compared Blocks 1 and 5, the Transfer effects test compared blocks 5 and 6, and the Recovery effects test compared Blocks 6 and 8. Interactions of these effects with ADHD status were tested by calculating differences between samples from the distributions of interest in each group and sampling from the difference score distributions to calculate an OR. Between-group main effects in each phase were tested by performing sample counts for between-group differences at each block within the phase (e.g., Block 1 ADHD vs. Block 1 Control, Block 2 ADHD vs. Block 2 control, etc.), summing the samples for which each group had a higher value, and using these summary counts to produce an OR.

Results

Traditional Performance Indices

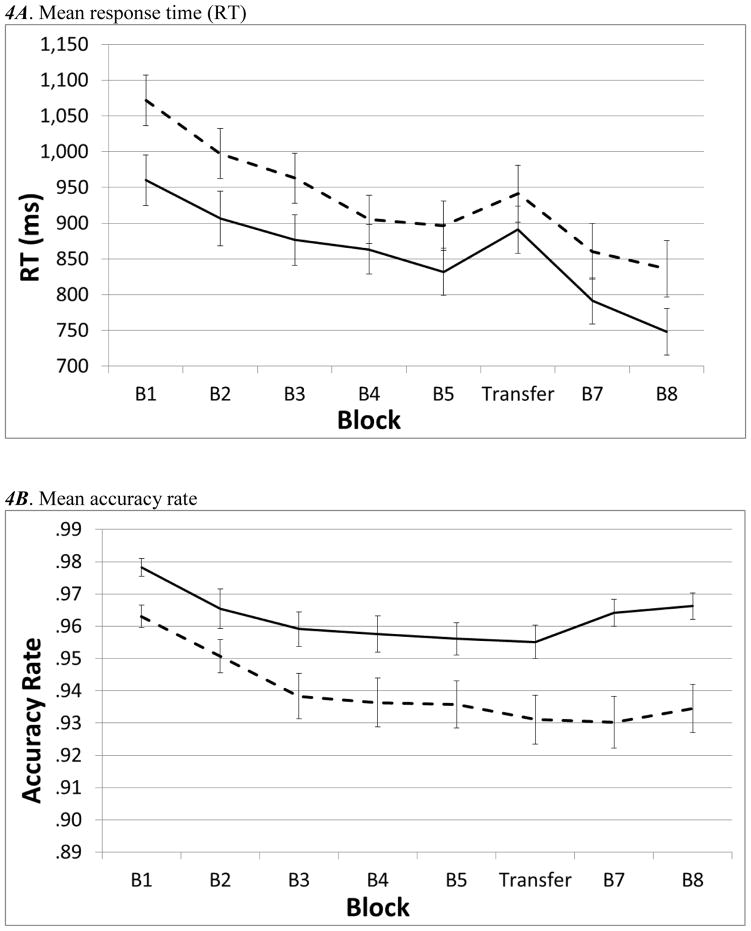

In RT, main effects of block were significant in the training, F(4,520)=46.24,η2=.26, p< .001, transfer, F(1,130)=22.34,η2=.15, p< 001, and recovery, F(2,260)=67.79,η2=.34, p<.001, phases of the task, and were in directions consistent with what would be expected if participants were displaying sequence-specific learning (see Figure 4A). Although visual inspection of the data (Figure 4A) appeared to indicate that children with ADHD were slower than controls on several blocks, no main effects of group or group x block interactions were detected (all p > .057, all η2 < .02), indicating that these differences were not strong or consistent. Accuracy decreased over training blocks, F(4,520)= 17.03, η2=.12p<.001, but did not display transfer, F(1,130)= 1.11, η2<.01p=.30, or recovery, F(2,260)= 2.74, η2=.02, p=.066, effects (Figure 4B). Children with ADHD were less accurate during training, F(1,130)= 7.51, η2=.06, p=.007, transfer, F(1,130)=6.62, η2=.05, p=.011 and recovery, F(1,130)=13.35, η2=.09, p<.001. Although no group x block interactions for accuracy were significant, (all p > .26, all η2 < .01), post-hoc analyses were conducted in the recovery phase because visual inspection of post-transfer accuracy scores indicated that participants in the control group may have displayed an increase in accuracy (see Figure B). These analyses revealed that controls displayed a large increase in accuracy during the recovery phase, F(2,130)=7.77,η2=.11, p=.001, while children with ADHD did not, F(2,130)=.342,η2<.001, p=.71.

Figure 4.

Learning effects in mean response times (ms) and accuracy. For all charts: dotted lines = ADHD, solid lines = controls. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Response Boundary

Boundaries (Figure 5A) decreased over training (OR>40,000:1), increased on the transfer block (OR=8.51:1), and decreased again in the recovery phase (OR=73.02:1), as would be expected if learning on the task reflected anticipatory responding to n+1 following the n trial. No significant group differences in response boundary were detected in any phase of the task (all OR<2.48:1) and there were no group x block interactions in the training, transfer or recovery phases (all OR<1.66:1)2.

Figure 5.

Learning effects in means of individual LBA parameters. For all charts: dotted lines = ADHD, solid lines = controls. Error bars represent standard error of the mean for parameter values across subjects.

Drift Rate

Drift rate to correct stimuli (Figure 5B) decreased over training (OR=485.21:1), increased during the transfer block (OR=5.57:1), and continued to increase in the recovery phase (OR=21.4:1). Reductions in vc over training suggest that controlled attention to the decision task is reduced as the learned sequence becomes automatic. Although there were no group differences in the training (OR=2.18:1) or transfer (OR=1.71:1) phases, children with ADHD had slower drift rates than controls in the recovery phase (OR=3.73:1).

During training, a significant group x block interaction was detected (OR=5.18:1), in which controls reduced their vc (OR=799:1), to a greater degree than children with ADHD (OR=171.41:1), suggesting that children with ADHD either have more difficulty acquiring automaticity, or their generally lower drift rate prevents them from reducing attention, without negatively affecting performance, to the same degree as controls. Crucially, a significant group x block interaction was also detected in the recovery phase (OR=3.8:1), in which the control group increased their vc between blocks 5–6 (OR=9.69:1), but children with ADHD did not (OR=1.44:1). This suggests that, consistent with prior work on conflict monitoring deficits in ADHD, children with ADHD are impaired in their ability to detect the conflict between the learned and transfer sequences, and are subsequently less capable of returning their full attention to the task. Because drift rate remained lower than controls during recovery, the performance of children with ADHD remained less accurate even after the originally trained sequence was returned. No group x block interaction was detected during the recovery phase (OR=2.82:1).

Nondecision Time

Nondecision time (Figure 5C) slightly decreased over training (OR=3.3:1), and slightly increased in the transfer phase (OR=3.3:1), but did not display a recovery effect (OR=1.24:1). Observation of the effect size and OR indicates that, relative to the effect in b, t0 makes minimal, if any, contribution to the RT effects observed in the training and transfer phases. These results are most consistent with the idea that t0 primarily represents RT improvement due to general task familiarity rather than sequence-specific learning. There were no effects of group or group x block interactions at any phase for this parameter (all OR < 2.77:1) 3.

Discussion

Even after complex behaviors have been mastered, the ability to monitor learned action sequences remains critical for adequate performance, because in everyday life, rapid changes in environmental demands are the rule. But despite the fact that performance monitoring processes have been implicated in prominent theories of ADHD (Albrecht et al., 2008; Barkley, 1997; Sergeant, 2000, 2005; Shiels & Hawk, 2010), such processes have typically been examined using tasks that do not index how complex behaviors are acquired, or later adapted. In addition, previous research has been dependent on traditional outcome variables to index performance like mean RT, which is an agglomeration of multiple component processes, including the speed of the perceptual decision making, stimulus encoding, speed-accuracy trade-off effects, and the initiation and coordination of the motor response. Using the LBA model, a well-validated formal model of RT that quantifies how multiple cognitive subprocesses interact during task performance, we found that children with ADHD demonstrated similar learning, transfer, and recovery effects over the course of a motor sequence learning paradigm (SRT) to those of non-ADHD controls. However, when the learned sequence was suddenly altered during a transfer block of trials, children with ADHD did not show the increase in attention to the task that characterized the response of their typically-developing peers. This later lead to poorer performance even after the return of the original learned sequence.

Response Boundary

More specifically, in non-human primate research, motor learning-related improvements in performance results from the earlier initiation of motor responses to predictable sensory events, rather than reductions in the speed of the motor response itself (Nixon & Passingham, 2001). Consistent with that body of work, and replicating a previous application of the LBA to the SRT task in young adults (Marshall & Visser, in preparation), we found that the boundary parameter (b) revealed strong sequence-specific learning effects. In both groups, b decreased consistently over the training phase, increased on the transfer phase, and decreased again during the recovery blocks, mirroring the changes in RT. As no group or group x block effects on response boundary were found, the acquisition of implicit motor sequence learning is unimpaired in ADHD, consistent with previous studies utilizing standard indices of performance (Karatekin et al., 2009; Laasonen et al., 2014; Vloet et al., 2010). These findings, combined with earlier findings of normal implicit contextual cueing (Weigard & Huang-Pollock, 2014) suggest that, despite compelling theoretical arguments to the contrary (e.g. Nigg & Casey, 2005; Sagvolden et al., 2005), the self-regulation deficits seen in ADHD are unlikely to be driven by an inability to learn/acquire implicit associations to help guide behavior.

That children with ADHD were capable of adjusting their response boundaries as flexibly as controls was somewhat surprising in light of research documenting the relative inflexibility of boundary adjustment when given explicit instructions to emphasize either response speed or accuracy (Mulder et al., 2010) and when altering response boundaries would lead to performance benefits (Weigard & Huang-Pollock, 2014). However, if boundary reductions in SRT reflect enhanced motor preparation for a specific, learned response on the n+1 trial rather than a general strategy to respond on less evidence, it is possible that the changes in response boundary in this context are not caused by the same mechanisms as those in previous studies. Strategic reductions in response thresholds are hypothesized to occur when fronto-striatal control systems release their tonic inhibition of motor systems (Bogacz et al., 2010; Forstmann et al., 2008; 2010), priming them to initiate responses earlier. Impairment in the strategic adjustment of response thresholds in ADHD, then, may reflect problems with the fronto-striatal systems that provide top-down influence on motor regions, while response threshold reductions linked to motor learning may be unimpaired because the motor systems themselves are intact. Regardless, further investigation into children with ADHD’s ability to adjust response boundaries in different situations is warranted in light of these findings.

Nondecision Time

Although nondecision time (t0) also decreased from the first training block to the final training block, the majority of this decrease took place between the first and second blocks (see Figure 5C), and there were no group differences. Furthermore, t0 displayed a marginal transfer effect, and no recovery effect, which serve as probes for the presence of sequence-specific learning. Therefore, unlike changes in b, changes in t0 likely reflect RT decreases in the early part of training due to general task familiarity. Task-general improvements in this parameter have also been shown in other learning paradigms that utilize a diffusion model framework (Dutilh et al., 2009, 2011; Weigard & Huang-Pollock, 2014). Because the SRT task is generally thought of as a motor learning task (Roberson, 2007; Schwarb & Schumacher, 2012), it might have been intuitive to expect that the t0 parameter which reflects, in part, the speed of the motor response (Brown & Heathcote, 2008), to demonstrate sequence specific effects. However, nondecision parameters capture the amount of time it takes to coordinate a motor response after the decision to initiate the response has already been made (Ratcliff & McKoon, 2008). In contrast, response boundaries determine how soon a motor process is initiated (Bogacz et al., 2010).

Drift Rate

Drift rate decreased substantially over the training phase in both groups, indicating that as the motor sequence became overlearned during the training phase, the allocation of controlled attention to the task decreased. These findings are consistent with PET and fMRI studies of motor sequence learning that brain activity in cortical regions mediating attention and cognitive control are reduced with learning (Jueptner et al., 1997; Poldrack et al., 2005). The loss of attention (i.e. vigilance decrements) commonly seen during sustained attention tasks (e.g. CPT) is distinct from situations in which attentional control is reduced as a complex process becomes automatic. In the former, ongoing attentional control is critical to the detection of rare targets, and the loss of that control leads to worse performance (Parasuraman & Davies, 1976; Parasuraman, 1979; Riccio et al., 2002). In the latter, the absence of that control does not impair performance (indeed, in such cases, engaging control is often disruptive to performance: Beilock, Carr, MacMahon, & Starkes, 2002; Beilock, Bertenthal McCoy, & Carr, 2004). As a complex motor learning task, the SRT falls into this latter category. Thus, the group x block interaction for drift during training trials, in which the reduction in drift rate was steeper over time for controls than ADHD, supports previous work demonstrating that children with ADHD have more difficulty developing automaticity for complex tasks (Huang-Pollock & Karalunas, 2010).

The slowing of drift rate during training is somewhat discrepant with prior literature on learning effects using evidence accumulation model parameters. Those studies reported increases in drift with practice (in which stimulus aspects of trial n predict the accurate response in trial n) (Dutilh et al., 2009: 2011; Weigard & Huang-Pollock, 2014). However, unlike the learning tasks previously under investigation, learning in the context of an SRT task is indexed by changes in boundary separation (in which trial n predicts trial n+1, leading to an earlier initiation of the response) rather than by drift rate. Any improvements in trial-specific drift rate that might have been seen in an SRT task would be offset by the much larger attention-related reductions in drift rate as the sequence became overlearned.

On the transfer block, when the learned SRT sequence was replaced with a novel sequence, and recognition of the deviations were critical for good performance, typically-developing children increased their attention to the task, which was reflected as an increase in drift rate. This response to the introduction of a novel sequence was absent among children with ADHD and lead to worse performance (i.e. lack of increases in accuracy) even after the learned sequence was returned in the recovery block.

Our results are consistent with a recent application of Aston-Jones and Cohen’s (2005) model of norepinephrine functioning to ADHD (i.e. Karalunas et al., 2014). Aston-Jones and Cohen (2005) have argued that as a neuroanatomical structure critical to performance monitoring (Botvinick et al., 2004; van Veen & Carter, 2002), the anterior cingulate modulates the phasic release of NE in response to external input about task performance. The phasic increase in NE in turn creates a temporal attentional filter that facilitates the processing of task-relevant stimuli. In describing how phasic NE optimizes performance, Aston-Jones and Cohen (2005) utilized the drift diffusion model to formally characterize the cognitive processes that contribute to performance. Applied to the current study, this would mean that the failure of children with ADHD to show a temporal increase in attention during the transfer block, as indexed by slow drift rate in that block, reflects an impairment in NE signaling, or in the monitoring processes that modulate that signaling.

Results could also be consistent with a recent model of ADHD which suggests that the slow, variable, and error prone performance, reflected by slow drift rates (e.g. Huang-Pollock, Karalunas, Tam & Moore, 2012; Karalunas, Huang-Pollock & Nigg, 2012; Karalunas & Huang-Pollock, 2013; Metin et al., 2013; Weigard & Huang-Pollock, 2014, in review), arise from a fundamental inability to meet the metabolic demands of firing neurons (Killeen, 2013; Killeen, Russell & Sergeant, 2013; Huang-Pollock, Ratcliff, McKoon, Shapiro, Weigard, & Galloway-Long, in review). Here, the mean drift rate among children with ADHD was non-significantly slower during training blocks, but when the cognitive (and presumably metabolic) demands of the task increased with the advent of the transfer block, strong group differences in drift appeared. The two models of ADHD presented here are not necessarily mutually exclusive; it remains possible that neuronal fatigue in the anterior cingulate or other relevant functional units could result in impaired NE signaling.

Limitations

Our interpretations of these data and their implication for our understanding of the mechanisms involved in the development of ADHD are accompanied by the following limitations. First, we interpret changes in drift rate as changes in attention, which is consistent with recent findings suggesting that a more attentive or aroused state can speed evidence accumulation (Kelly & O’Connell, 2013; Rae et al., 2014). However, future research utilizing psychophysiological measures of the construct are needed to provide converging evidence for this interpretation of performance on the SRT task. Second, accuracy was high for both groups, which probably lead to poor model fit for errors because the likelihood function at each set of the sampling was influenced to a much greater degree by how well the correct, rather than error, trials were described by the model. This is not a significant concern for the current study because model parameters directly constrained by correct RTs were used in analyses. However, data interpretation could be impacted if, for some reason, errors are more generally not well explained by the competing accumulator model framework. Reassuringly, this remains a distant possibility because the LBA has been repeatedly validated for multiple-choice tasks (Brown & Heathcote, 2008; Donkin, Averall, Brown & Heathcote, 2009; Ho, Brown & Serences, 2009; van Maanan et al., 2012), including the SRT task itself (Marshall & Visser, in preparation). However, it is recommended that future replications vary trial difficulty in the SRT to produce a larger range of errors.

Conclusion

Performance monitoring during the execution of otherwise automatic action sequences is essential for making adjustments to behavior when changes in the environment make learned behaviors inappropriate. By applying the LBA model to data from a learning task that is well established in the cognitive neuroscience literature, we have shown that although children with ADHD were able to implicitly learn a sequence of motor responses, they displayed a diminished reaction to a change in the task that eliminated the benefits of the learned sequence. Specifically, they did not demonstrate the quick reorientation of attention to the task that their typically developing peers appeared to, resulting in worse subsequent performance. These results extend previous research on performance monitoring in ADHD, highlight the roles of conflict monitoring and attention in the execution of implicitly learned behavior, provide converging evidence for explanations of slowed information processing in the disorder that emphasize monitoring and changes in cognitive demands, and demonstrate the utility of applying cutting edge evidence accumulation models to clinical data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH084947 to Cynthia Huang-Pollock. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. We also thank the parents, teachers, and children who participated, and the tireless research assistants who helped in the conduct of the study.

Footnotes

Barnes et. al. (2010) used a non-standard “alternating” variation on the SRT that created very different task demands than the more commonly used paradigms in the literature.

Although NHST analyses for the Group x Block interaction in the transfer phase indicated a significant effect F(4,520)=5.87,η2=.04, p=.017, the OR was unconvincing (OR=1.66:1), reinforcing interpretation that there are no ADHD-related group differences in the implicit learning of motor sequences.

For the main effect of Block in the transfer phase, the NHST result was marginally non-significant, F(4,520)=3.40, η2=03, p=.068, while the OR was weak, but positive, (3.3:1). The overall impression, however, is that t0 makes little contribution to sequence specific learning on the SRT task.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Alexander Weigard, The Pennsylvania State University.

Cynthia Huang-Pollock, The Pennsylvania State University.

Scott Brown, The University of Newcastle, Australia.

References

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, D.C: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht B, Brandeis D, Uebel H, Heinrich H, Mueller UC, Hasselhorn M, … Banaschewski T. Action monitoring in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, their nonaffected siblings, and normal control subjects: Evidence for an endophenotype. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64(7):615–625. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annual Reviews of Neuroscence. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogh L, Czobor P. Post-Error Slowing in Patients With ADHD A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1087054714528043. 1087054714528043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(1):65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes KA, Howard JH, Jr, Howard DV, Kenealy L, Vaidya CJ. Two forms of implicit learning in childhood ADHD. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35(5):494–505. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2010.494750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilock SL, Bertenthal BI, McCoy AM, Carr TH. Haste does not always make waste: Expertise, direction of attention, and speed versus accuracy in performing sensorimotor skills. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2004;11(2):373–379. doi: 10.3758/bf03196585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilock SL, Carr TH, MacMahon C, Starkes JL. When paying attention becomes counterproductive: impact of divided versus skill-focused attention on novice and experienced performance of sensorimotor skills. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2002;8(1):6. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.8.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogacz R, Wagenmakers EJ, Forstmann BU, Nieuwenhuis S. The neural basis of the speed–accuracy tradeoff. Trends in Neurosciences. 2010;33(1):10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review. 2001;108(3):624. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, Carter CS. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8(12):539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Nystrom LE, Fissell K, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring versus selection-for-action in anterior cingulate cortex. Nature. 1999;402(6758):179–181. doi: 10.1038/46035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Heathcote A. The simplest complete model of choice response time: Linear ballistic accumulation. Cognitive Psychology. 2008;57(3):153–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio-Murphy A, Klorman R, Shaywitz SE, Fletcher JM, Marchione KE, Holahan J, … Shaywitz BA. Error-related event-related potentials in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, reading disorder, and math disorder. Biological Psychology. 2007;75(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners’ Rating Scales—Revised Technical Manual. NY: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Destrebecqz A, Cleeremans A. Can sequence learning be implicit? New evidence with the process dissociation procedure. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2001;8(2):343–350. doi: 10.3758/bf03196171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin C, Averell L, Brown S, Heathcote A. Getting more from accuracy and response time data: Methods for fitting the linear ballistic accumulator. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(4):1095–1110. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin C, Brown SD, Heathcote A. The overconstraint of response time models: Rethinking the scaling problem. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16(6):1129–1135. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul G, Power T, Anastopoulos A, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. New York: Guildford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dutilh G, Krypotos AM, Wagenmakers EJ. Task-related versus stimulus-specific practice: A diffusion model account. Experimental Psychology. 2011;58(6):434. doi: 10.1027/1618-3169/a000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutilh G, Vandekerckhove J, Tuerlinckx F, Wagenmakers EJ. A diffusion model decomposition of the practice effect. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16(6):1026–1036. doi: 10.3758/16.6.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin C, Brown SD, Heathcote A. The overconstraint of response time models: Rethinking the scaling problem. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16(6):1129–1135. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin C, Brown S, Heathcote A, Wagenmakers EJ. Diffusion versus linear ballistic accumulation: different models but the same conclusions about psychological processes? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2011;18(1):61–69. doi: 10.3758/s13423-010-0022-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimer M, Goschke T, Schlaghecken F, Stürmer B. Explicit and implicit learning of event sequences: evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1996;22(4):970. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.22.4.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand NK, Mecklinger A, Kray J. Error and deviance processing in implicit and explicit sequence learning. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20(4):629–642. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstmann BU, Anwander A, Schäfer A, Neumann J, Brown S, Wagenmakers EJ, … Turner R. Cortico-striatal connections predict control over speed and accuracy in perceptual decision making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(36):15916–15920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004932107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstmann BU, Dutilh G, Brown S, Neumann J, Von Cramon DY, Ridderinkhof KR, Wagenmakers EJ. Striatum and pre-SMA facilitate decision-making under time pressure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(45):17538–17542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805903105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geburek AJ, Rist F, Gediga G, Stroux D, Pedersen A. Electrophysiological indices of error monitoring in juvenile and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—A meta-analytic appraisal. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2013;87(3):349–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groen Y, Wijers AA, Mulder LJ, Waggeveld B, Minderaa RB, Althaus M. Error and feedback processing in children with ADHD and children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder: an EEG event-related potential study. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008;119(11):2476–2493. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang-Pollock CL, Karalunas SL. Working memory demands impair skill acquisition in children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(1):174. doi: 10.1037/a0017862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang-Pollock CL, Karalunas SL, Tam H, Moore AN. Evaluating vigilance deficits in ADHD: a meta-analysis of CPT performance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(2):360. doi: 10.1037/a0027205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang-Pollock CL, Maddox WT, Tam H. Rule-Based and Information- Integration Perceptual Category Learning in Children With Attention- Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuropsychology. 2014;28(4):594–604. doi: 10.1037/neu0000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang-Pollock CL, Ratcliff R, McKoon G, Shapiro S, Weigard A, Galloway-Long H. Using the diffusion decision model to explain cognitive deficits in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0151-y. in review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TC, Brown S, Abuyo NA, Ku EHJ, Serences JT. Perceptual consequences of feature-based attentional enhancement and suppression. Journal of Vision. 2012;12(8):15. doi: 10.1167/12.8.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TC, Brown S, Serences JT. Domain general mechanisms of perceptual decision making in human cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(27):8675–8687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5984-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TC, Yang G, Wu J, Cassey P, Brown SD, Hoang N, … Yang TT. Functional connectivity of negative emotional processing in adolescent depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;155:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JH, Mutter SA, Howard DV. Serial pattern learning by event observation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1992;18(5):1029. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.18.5.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby LL. A process dissociation framework: Separating automatic from intentional uses of memory. Journal of Memory and Language. 1991;30(5):513–541. [Google Scholar]

- Janacsek K, Nemeth D. Implicit sequence learning and working memory: correlated or complicated? Cortex. 2013;49(8):2001–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman LM, van Melis JJ, Kemner C, Markus CR. Methylphenidate improves deficient error evaluation in children with ADHD: an event-related brain potential study. Biological Psychology. 2007;76(3):217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jueptner M, Stephan KM, Frith CD, Brooks DJ, Frackowiak RSJ, Passingham RE. Anatomy of motor learning. I. Frontal cortex and attention to action. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77(3):1313–1324. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalunas SL, Geurts HM, Konrad K, Bender S, Nigg JT. Annual Research Review: Reaction time variability in ADHD and autism spectrum disorders: measurement and mechanisms of a proposed trans-diagnostic phenotype. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55(6):685–710. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalunas SL, Huang-Pollock CL. Integrating Impairments in Reaction Time and Executive Function Using a Diffusion Model Framework. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(5):837–850. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9715-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalunas SL, Huang-Pollock CL, Nigg JT. Decomposing Attention- Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)-Related Effects in Response Speed and Variability. Neuropsychology. 2012;26(6):684–694. doi: 10.1037/a0029936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatekin C, White T, Bingham C. Incidental and intentional sequence learning in youth-onset psychosis and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Neuropsychology. 2009;23(4):445. doi: 10.1037/a0015562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90(430):773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Keele SW, Ivry R, Mayr U, Hazeltine E, Heuer H. The cognitive and neural architecture of sequence representation. Psychological Review. 2003;110(2):316. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SP, O’Connell RG. Internal and external influences on the rate of sensory evidence accumulation in the human brain. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33(50):19434–19441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3355-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR. Absent without leave; a neuroenergetic theory of mind wandering. Frontiers in psychology. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR, Russell VA, Sergeant JA. A behavioral neuroenergetics theory of ADHD. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37(4):625–657. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laasonen M, Väre J, Oksanen-Hennah H, Leppämäki S, Tani P, Harno H, … Cleeremans A. Project DyAdd: Implicit learning in adult dyslexia and ADHD. Annals of Dyslexia. 2014;64(1):1–33. doi: 10.1007/s11881-013-0083-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, McBurnett K, Biederman J, Greenhill L, … Hynd GW, et al. DSM-IV field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1673–1685. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotti M, Pliszka SR, Perez R, Kothmann D, Woldorff MG. Abnormal brain activity related to performance monitoring and error detection in children with ADHD. Cortex. 2005;41(3):377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse K, Wadden K, LAB Motor skill acquisition across short and long time scales: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging data. Neuropsychologia. 2014;59:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce RD. Response Times. 8. Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall T, Visser I. Digging deeper in Implicit Learning: An LBA decomposition of the Serial Reaction Time Task. 2009 Manuscript in revision. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr U. Spatial attention and implicit sequence learning: Evidence for independent learning of spatial and nonspatial sequences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1996;22(2):350. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.22.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metin B, Roeyers H, Wiersema JR, van der Meere JJ, Thompson M, Sonuga-Barke E. ADHD performance reflects inefficient but not impulsive information processing: A diffusion model analysis. Neuropsychology. 2013;27(2):193–200. doi: 10.1037/a0031533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder MJ, Bos D, Weusten JM, van Belle J, van Dijk SC, Simen P, … Durston S. Basic impairments in regulating the speed-accuracy tradeoff predict symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(12):1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Casey BJ. An integrative theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on the cognitive and affective neurosciences. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17(03):785–806. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen MJ, Bullemer P. Attentional requirements of learning: Evidence from performance measures. Cognitive Psychology. 1987;19(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon PD, Passingham RE. Predicting sensory events. Experimental Brain Research. 2001;138(2):251–257. doi: 10.1007/s002210100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman R. Memory load and event rate control sensitivity decrements in sustained attention. Science. 1979;205(4409):924–927. doi: 10.1126/science.472714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman R, Davies DR. Decision theory analysis of response latencies in vigilance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1976;2(4):578. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.2.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher TM, Piek JP, Hay DA. Fine and gross motor ability in males with ADHD. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2003;45(8):525–535. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Sabb FW, Foerde K, Tom SM, Asarnow RF, Bookheimer SY, Knowlton BJ. The neural correlates of motor skill automaticity. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(22):5356–5364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3880-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rae B, Heathcote A, Donkin C, Averall L, Brown S. The hare and the tortoise: Emphasizing speed can change the evidence used to make decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition. 2014;40:1226–1243. doi: 10.1037/a0036801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R. A theory of memory retrieval. Psychological Review. 1978;85(2):59. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.95.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Love J, Thompson CA, Opfer JE. Children Are Not Like Older Adults: A Diffusion Model Analysis of Developmental Changes in Speeded Responses. Child Development. 2012;83(1):367–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Thapar A, Gomez P, McKoon G. A diffusion model analysis of the effects of aging in the lexical-decision task. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):278. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Thapar A, Mckoon G. A diffusion model analysis of the effects of aging on brightness discrimination. Perception & Psychophysics. 2003;65(4):523–535. doi: 10.3758/bf03194580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, McKoon G. The diffusion decision model: theory and data for two-choice decision tasks. Neural Computation. 2008;20(4):873–922. doi: 10.1162/neco.2008.12-06-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Thapar A, McKoon G. Effects of aging and IQ on item and associative memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2011;140(3):464. doi: 10.1037/a0023810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Thapar A, McKoon G. The effects of aging on reaction time in a signal detection task. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16(2):323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Thapar A, Gomez P, McKoon G. A diffusion model analysis of the effects of aging in the lexical-decision task. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):278. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Tuerlinckx F. Estimating parameters of the diffusion model: Approaches to dealing with contaminant reaction times and parameter variability. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2002;9(3):438–481. doi: 10.3758/bf03196302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed J, Johnson P. Assessing implicit learning with indirect tests: Determining is learned about sequence structure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1994;20(3):585. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. Behavior Assessment for Children, (BASC-2) Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Riccio CA, Reynolds CR, Lowe P, Moore JJ. The continuous performance test: a window on the neural substrates for attention? Archives of clinical neuropsychology. 2002;17(3):235–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof KR, Forstmann BU, Wylie SA, Burle B, van den Wildenberg WP. Neurocognitive mechanisms of action control: resisting the call of the Sirens. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2011;2(2):174–192. doi: 10.1002/wcs.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof KR, van den Wildenberg WP, Segalowitz SJ, Carter CS. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: the role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward-based learning. Brain and Cognition. 2004;56(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson EM. The serial reaction time task: implicit motor skill learning? The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(38):10073–10075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2747-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelse NN, Altink ME, Fliers EA, Martin NC, Buschgens CJ, Hartman CA, … Oosterlaan J. Comorbid problems in ADHD: degree of association, shared endophenotypes, and formation of distinct subtypes. Implications for a future DSM. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(6):793–804. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9312-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagvolden T, Johansen EB, Aase H, Russell VA. A dynamic developmental theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and combined subtypes. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28(3):397–418. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachar RJ, Chen S, Logan GD, Ornstein TJ, Crosbie J, Ickowicz A, Pakulak A. Evidence for an error monitoring deficit in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2004;32(3):285–293. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000026142.11217.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedek F, Oberauer K, Wilhelm O, Süß HM, Wittmann WW. Individual differences in components of reaction time distributions and their relations to working memory and intelligence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2007;136(3):414. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarb H, Schumacher EH. Generalized lessons about sequence learning from the study of the serial reaction time task. Advances in Cognitive Psychology. 2012;8(2):165. doi: 10.2478/v10053-008-0113-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant J. The cognitive-energetic model: an empirical approach to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant JA. Modeling attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a critical appraisal of the cognitive-energetic model. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1248–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant JA, Van der Meere J. What happens after a hyperactive child commits an error? Psychiatry Research. 1988;24(2):157–164. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas R. NIMH Diagnostic INterview Schedule for Children- IV. New York: Ruane Center for Early Diagnosis, Division of Child Psychiatry, Columbia University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shanks DR. Learning: From Association to Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:273–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels K, Hawk LW., Jr Self-regulation in ADHD: The role of error processing. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(8):951–961. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels K, Tamm L, Epstein JN. Deficient post-error slowing in children with ADHD is limited to the inattentive subtype. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2012;18(03):612–617. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PL, Ratcliff R. Psychology and neurobiology of simple decisions. Trends in Neurosciences. 2004;27(3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PL, Ratcliff R, Wolfgang BJ. Attention orienting and the time course of perceptual decisions: Response time distributions with masked and unmasked displays. Vision research. 2004;44(12):1297–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol J, Voss A, Bowen HJ, Grady CL. Motivational incentives modulate age differences in visual perception. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(4):932. doi: 10.1037/a0023297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BM, Sederberg PB, Brown SD, Steyvers M. A method for efficiently sampling from distributions with correlated dimensions. Psychological Methods. 2013;18(3):368. doi: 10.1037/a0032222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Maanen L, Grasman RP, Forstmann BU, Keuken MC, Brown SD, Wagenmakers EJ. Similarity and number of alternatives in the random-dot motion paradigm. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2012;74(4):739–753. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0267-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]