Abstract

Objective

This paper aims to (1) assess whether promotion of tax-free sales among Internet cigarette vendors (ICVs) changed between 2009 and 2011, (2) determine which types of ICVs are most likely to promote tax-free sales (e.g., US-based, international, or mixed location ICVs), and (3) compare the price of cigarettes advertised in ICVs to prices at brick-and-mortar retail outlets.

Methods

We analyzed data from the 200 most popular ICVs in 2009, 2010, and 2011 to assess promotion of tax-free sales and the price of Marlboro cigarette cartons. We used Nielsen scanner data from 2009, 2010, and 2011 to measure the price of Marlboro cartons in US grocery stores.

Findings

The odds of ICVs claiming tax-free status were higher in 2011 than in 2009 (odds ratio (OR)=1.58, p<.01). Mixed location and international vendors had higher odds of promoting tax-free sales than US-based ICVs (OR=4.95 and 6.23 respectively, both p<.001). In 2011, the average price of one Marlboro carton was $35.27 online, compared to $52.73 in US grocery stores. We estimated that in 2011, a pack-a-day smoker living in an area with high cigarette prices would save $1,508 per year buying cigarettes online.

Conclusions

ICVs commonly promote tax-free sales, and cigarettes are cheaper online compared to US grocery stores. Better enforcement of the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act is needed to address tax-free cigarette sales among ICVs.

Keywords: Economics, illegal tobacco products, price, taxation

INTRODUCTION

US Internet cigarette vendors (ICVs) often neglect to pay cigarette excise taxes, depriving governments of tax revenue and undermining the public health benefit of higher taxes.[1] To curtail Internet cigarette sales, the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking (PACT) Act went into effect in 2010. In addition to requiring age verification for online cigarette sales, the PACT Act sought to strengthen the 1949 Jenkins Act, which requires cigarette vendors that ship products over state lines to report sales information to the receiving states.[2] The PACT Act includes stronger penalties for ICVs that fail to pay taxes and provides enforcement tools to state and federal agencies responsible for monitoring ICV cigarette sales.[3, 4] Finally, the PACT Act prohibits cigarettes and smokeless tobacco from being mailed through the US Postal Service, UPS, FedEx, and DHL.[4] Enforcing the PACT Act among international ICVs may be difficult as international vendors often claim to sell cigarettes from so-called “duty-free” zones.[1, 5] Native American-run ICVs present an additional challenge because they have been known to export tax-free cigarettes off of sovereign lands to non-Native consumers.[6]

Passage of the PACT Act coincided with cigarette tax increases at the state and federal level. In 2009, state cigarette taxes increased in 15 states[7] and the federal cigarette tax increased to $1.01.[8] Cigarette tax increases may motivate price-sensitive smokers to seek low-tax or tax-free cigarettes, despite restrictions put in place by the PACT Act.[9] Monitoring trends in cigarette prices and promotion of tax-free sales among ICVs can augment our understanding of tobacco control policies, such as the PACT Act and cigarette tax increases. This study aims to (1) assess whether promotion of tax-free cigarette sales among ICVs changed between 2009 and 2011, (2) determine which types of ICVs were most likely to promote tax-free sales, and (3) compare the price of cigarettes at ICVs to the price in grocery stores.

METHODS

Website Identification and Coding

We used automated searches with manual screening to identify the 200 most visited English-language ICVs in 2009, 2010, and 2011, based on visitor traffic data. Twenty-eight sites appeared in one year, 133 sites appeared in two years, and 39 sites appeared in all three years. Two raters independently coded offline archival copies of websites; discrepancies were resolved by senior staff. The study’s methodology has been described in detail elsewhere.[1, 10, 11]

Measures

Four variables assessed promotion of tax-free sales: whether ICVs claimed that they (1) do not pay federal or state taxes, (2) do not comply with the Jenkins Act, (3) sold or shipped cigarettes from a duty-free zone, or (4) had tax-free status. We then created a composite variable representing whether ICVs promoted tax-free sales (i.e., coded as exhibiting any of the four tax variables).

We classified vendor location into three categories: international-only (vendors located outside the US), US-only (vendors with no international affiliation), and mixed location (vendors with Native American affiliation or with US-based and international components). These vendor types were combined into the “mixed location” category because they had some features (e.g., phone number) indicating they were located in the US, while having other features (e.g., shipping products from overseas or sovereign Native American land) indicating they may consider themselves to be outside US jurisdiction.

Price analyses examined the price of Marlboro cigarettes as this is the leading cigarette brand among US smokers.[12] We first calculated the price of one carton of Marlboro cigarettes plus shipping for each ICV. Then, we used Scantrack™ data from the Nielsen Company to measure the average price of Marlboro cartons sold in grocery stores. Nielsen price data were adjusted for inflation using 2011 as the reference. Nielsen collects scanner data in 52 designated market areas (DMAs), which are collections of counties around a metropolitan area. Although most smokers buy cigarettes from convenience stores, we used grocery store prices because smokers buying cigarettes at grocery stores are more likely to purchase cartons (vs. packs) than smokers who buy cigarettes at convenience stores; thus grocery prices are a more appropriate comparison to cartons purchased online.[13] Moreover, Nielsen grocery store data were available for all 52 DMAs whereas convenience store data were only available for 30 DMAs.

Analysis

We conducted logistic regression using generalized estimating equations to account for the non-independence of websites in multiple waves.[14] The model estimated whether the odds of promoting tax-free sales varied by year and vendor location. We calculated the mean Marlboro carton price in the lowest quartile of ICVs to reflect the fact that the online environment readily enables smokers to find a lower-than-average price by comparison shopping. We calculated the median price of Marlboro cartons in grocery stores. Then, we divided the Nielsen DMAs into quartiles based on the mean price of one Marlboro carton in each DMA, and computed the mean Marlboro carton price in the lowest and highest quartiles. The lowest quartile represents areas with low cigarette prices (e.g., St. Louis, Missouri), and the highest quartile represents areas with high prices (e.g., New York City, New York). Finally, we estimated the amount of money that a pack-a-day smoker would save annually buying cigarettes online, rather than in a grocery store.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics for vendor type and prevalence of tax variables can be found in Appendix 1 and 2. After controlling for vendor location, the odds of ICVs claiming tax-free status were higher in 2010 and 2011, compared to 2009 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Generalized estimating equations predicting odds of promoting tax-free sales among Internet cigarette vendors, by year and location

| Year | Website claims that vendor sells from duty free zone |

Website claims that vendor does not pay federal/state taxes |

Website claims that vendor does not abide by Jenkins Act1 |

Website claims tax- free status |

Website promotes tax-free sales2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 (ref) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2010 | 1.12 | 1.38 | 1.09 | 1.58** | 1.39 |

| 2011 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 1.45* | 0.96 |

| US vendors (ref) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

|

Mixed location vendors |

N/A | 2.39 | 3.29** | 6.62*** | 4.95*** |

|

International vendors |

N/A | 2.94* | 3.46** | 5.37** | 6.23*** |

Notes: overall n=600 (200 sites per year)

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<.001

Models specified an exchangeable working correlation structure

US law requiring cigarette vendors that ship products over state lines to report sales information to the receiving state’s tax department

Composite of the first four variables in this table

-- indicates reference category

N/A indicates that comparison could not be made because none of the US vendors reported selling from duty free zones

Controlling for year of data collection, mixed location and international vendors were more likely to promote tax-free sales than US ICVs. Mixed location ICVs had higher odds of claiming noncompliance of the Jenkins Act and tax-free status than US ICVs. Compared to US vendors, international vendors had higher odds of claiming that they do not pay federal/state taxes, do not abide by the Jenkins Act, and have tax-free status.

In 2009, 2010 and 2011, the mean Marlboro carton prices in the lowest ICV price quartile were $22.09, $25.28, and $28.64, respectively (Appendix 3 contains more price data). Marlboro prices were higher at grocery stores; in 2009, the mean price in the lowest quartile was $40.46 and $61.33 in the highest quartile. In 2010, the mean price in the lowest price quartile was $43.06 and $69.09 in the highest quartile. In 2011, the mean price in the lowest quartile was $42.74 and $70.53 in the highest quartile. A pack-a-day smoker living in an area with high cigarette prices buying cigarettes online could save $1,412 in 2009, $1,577 in 2010, and $1,508 in 2011. Even consumers living in areas with the lowest cigarette prices could see substantial savings, as much as $661 in 2009, $640 in 2010, and $508 in 2011.

CONCLUSIONS

ICVs were more likely to claim tax-free status in 2010 and 2011 than in 2009. Mixed location and international ICVs were much more likely to promote tax-free sales than US-based vendors. Our estimate of the percentage of ICVs claiming tax-free status in 2011 (33%) is identical to the estimate from a 1999 study of 88 ICVs.[15] Duty-free sales appear to have marginally declined in the past 15 years; the 1999 study found that 22% of ICVs promoted duty-free sales, compared to 18% in the current study.[15]

We also found that cigarette prices were substantially higher at US grocery stores than at ICVs; a pack-a-day smoker could save more than $1,500 per year buying cigarettes online. Prior studies have suggested that cigarettes are cheaper online than at brick-and-mortar retailers. Hodge et al. (2004) found that the price of one Marlboro carton ranged from $26.00 to $36.85 among 33 ICVs, compared to $46.99 in grocery stores.[16] Pesko et al. (2014) analyzed data from the 2009–2010 National Adult Tobacco Survey,[17] finding that smokers who bought cigarettes online at least once in the previous year saved $5.70 per carton on their most recent purchase; however, this purchase may or may not have been from an ICV.[17]

Although we did not examine the reasons for changes in tax-free claims over time, our data indicate that ICVs commonly promote tax-free cigarette sales and sell cigarettes at cheaper prices than retail outlets. The sale of untaxed cigarettes not only deprives governments of tax revenue but also poses a threat to public health as higher cigarette prices reduce cigarette consumption.[18] However, smokers may avoid excise taxes in areas with high cigarette taxes, as demonstrated in a longitudinal study of US smokers.[19] As Internet access becomes ubiquitous,[20] price-sensitive smokers may seek cheaper cigarettes online in response to tax increases. Indeed, one study found a large increase in tax avoidance-related Google searches the week of the 2009 federal tax increase, including a 557% increase in searches for “free cigarettes online”.[9] Our study underscores the need for better enforcement of the PACT Act to prevent the illegal sale of untaxed cigarettes online.

This study has several limitations. First, the study only covers a three-year time span without controlling for secular trends. Changes in the make-up of the ICVs included in the study could potentially explain the observed time trends. Finally, the observational study design precluded us from drawing causal inferences about the impact of tobacco control policies on the study outcomes.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

Previous research has found that US Internet cigarette vendors (ICVs) neglect to pay cigarette excise taxes.

Recent trends in ICVs’ promotion of tax-free cigarette sales and cigarette prices have not yet been explored.

We found that ICVs were more likely to claim tax-free status in 2010 and 2011 than in 2009, and that international ICVs and mixed location ICVs were more likely to promote tax-free sales than US-based ICVs.

Marlboro cigarettes were substantially cheaper on the Internet than at US grocery stores.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jason Derrick, Daniel Dench, and J. Michael Bowling for their guidance and help with data analysis and management.

FUNDING

Effort for M. G. Hall was supported by grant number 5R01CA169189-02 from NCI, and grant number 64747 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Substance Abuse Policy Research Program.

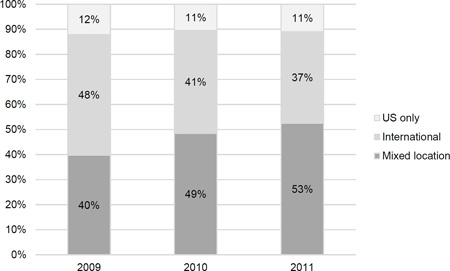

Appendix 1. Location attributes of Internet Cigarette Vendors, 2009–2011 (n=200)

Note. Mixed location vendors are those with Native American affiliation or with US-based and international components.

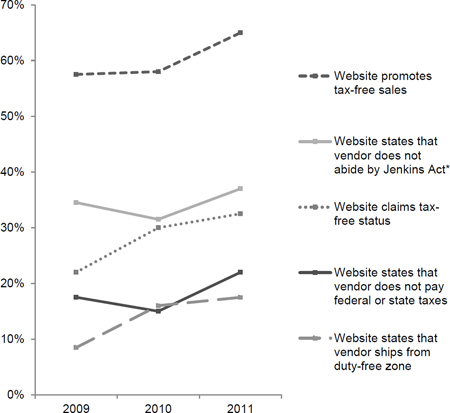

Appendix 2. Percentage of Internet cigarette vendors that promoted tax-free status in 2009, 2010, and 2011

* The Jenkins Act is a US law requiring cigarette vendors that ship products over state lines to report sales information to the receiving state’s tax department

Appendix 3. Price (USD) of one Marlboro carton purchased online, compared to prices at grocery stores from 2009–2011

| Year | Internet cigarette vendorst |

US grocery stores | Projected annual savings if purchased online* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean of lowest quartile |

Median | Mean of lowest quartile |

Median | Mean of highest quartile |

Compared to mean price of lowest quartile at grocery stores |

Compared to median price at grocery stores |

Compared to mean price of highest quartile at grocery stores |

|

| 2009 | $22.09 | $40.08 | $40.46 | $49.18 | $61.33 | $661.32 | $975.24 | $1,412.64 |

| 2010 | $25.28 | $44.00 | $43.06 | $54.20 | $69.09 | $640.08 | $1,041.12 | $1,577.16 |

| 2011 | $28.64 | $35.27 | $42.74 | $52.73 | $70.53 | $507.60 | $867.24 | $1,508.04 |

We calculated the projected annual savings for someone who purchased cigarettes online at the mean price of the lowest quartile, compared to the mean price of the highest quartile at US grocery stores because individuals in higher tax jurisdictions have the greatest incentive to purchase cigarettes online.

n=126 in 2009, 117 in 2010, and 105 in 2011

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTORS

MGH helped formulate the research, analyzed the data and drafted the paper. RSW formulated the research, oversaw data collection, drafted sections of the paper, and edited multiple drafts of the paper. DGG analyzed price data and edited multiple drafts of the paper. KMR formulated the research and edited multiple drafts of the paper.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This study did not involve human subjects research and was thus exempt from ethical review.

COMPETING INTEREST

In the past, Dr. Kurt M. Ribisl has served as an Expert Consultant in litigation against Internet tobacco vendors for violating taxation and youth access laws.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ribisl KM, Kim AE, Williams RS. Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine; 2007. Sales and marketing of cigarettes on the internet: Emerging threats to tobacco control and promising policy solutions. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Public Laws. Jenkins Act of 1949. 15 U.S. Code 375. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickey B. The PACT Act: Preventing illegal Internet sales of cigarettes & smokeless tobacco. Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Public Laws. Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act of 2010; 111th Congress. Public Law 111-154. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Free-trade zone. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderman J. Strategies to combat illicit tobacco trade. St. Paul, Minnesota: Tobacco Control Legal Consortium; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State cigarette excise taxes-United States, 2009. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2010;59(13):385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Public Laws. Children’s health insurance program reauthorization act of 2009; 111th Congress. Public Law 111-3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Ribisl KM, et al. Digital detection for tobacco control: online reactions to the 2009 U. S. cigarette excise tax increase. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2014;16(5):576–583. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribisl KM, Williams RS, Gizlice Z, et al. Effectiveness of state and federal government agreements with major credit card and shipping companies to block illegal Internet cigarette sales. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Internet Cigarette Vendor Compliance With Credit Card Payment and Shipping Bans. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco brand preferences. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emery S, White MM, Gilpin E, et al. Was there significant tax evasion after the 1999 50 cent per pack cigarette tax increase in California? Tob Control. 2002;11(2):130–134. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribisl KM, Kim AE, Williams RS. Web sites selling cigarettes: how many are there in the USA and what are their sales practices? Tob Control. 2001;10(4):352–359. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodge FS, Geishirt Cantrell BA, Struthers R, et al. American Indian internet cigarette sales: another avenue for selling tobacco products. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):260–261. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pesko MF, Xu X, Tynan MA, et al. Per-pack price reductions available from different cigarette purchasing strategies: United States, 2009–2010. Prev Med. 2014;63:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaloupka FJ. Macro-social influences: the effects of prices and tobacco-control policies on the demand for tobacco products. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 1999;1(Suppl 1):S105–S109. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornelius ME, Driezen P, Hyland A, et al. Trends in cigarette pricing and purchasing patterns in a sample of US smokers: findings from the ITC US surveys (2002–2011) Tob Control. 2014 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Census Bureau. Computer and internet use in the United States. 2013. [Google Scholar]