Abstract

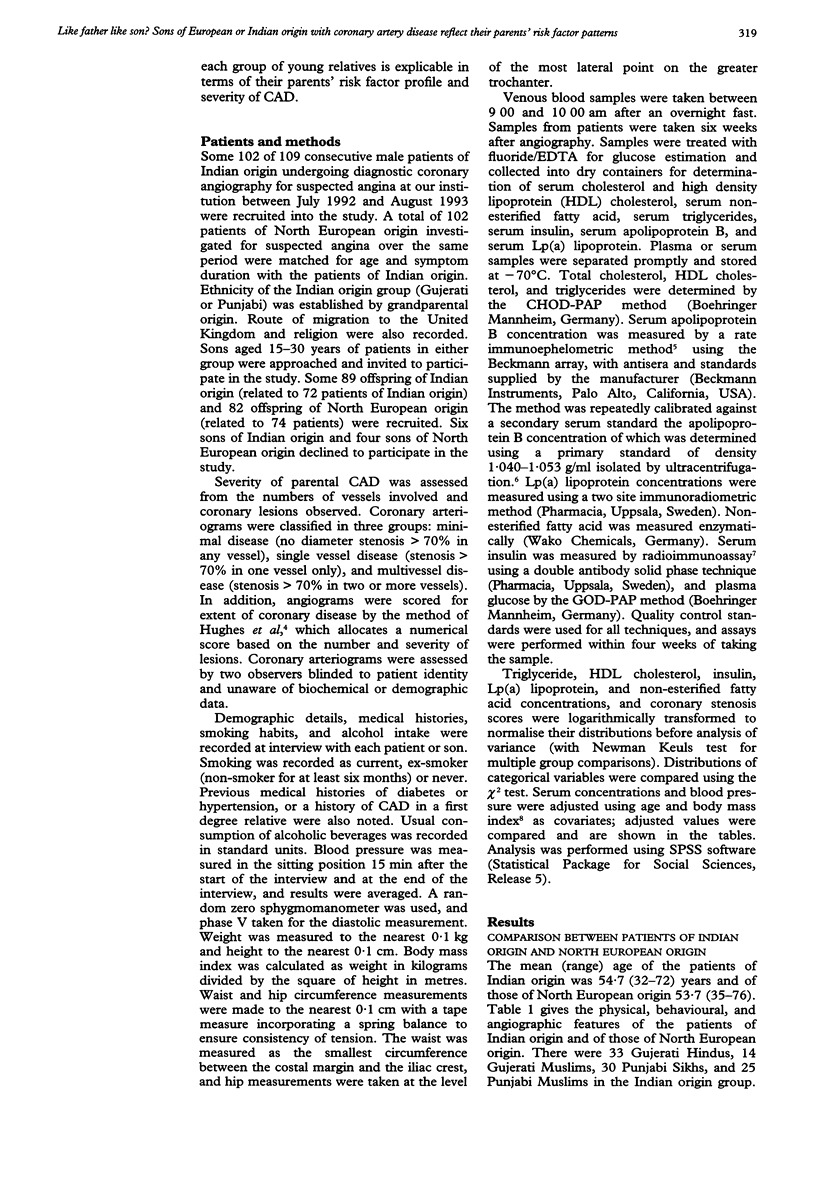

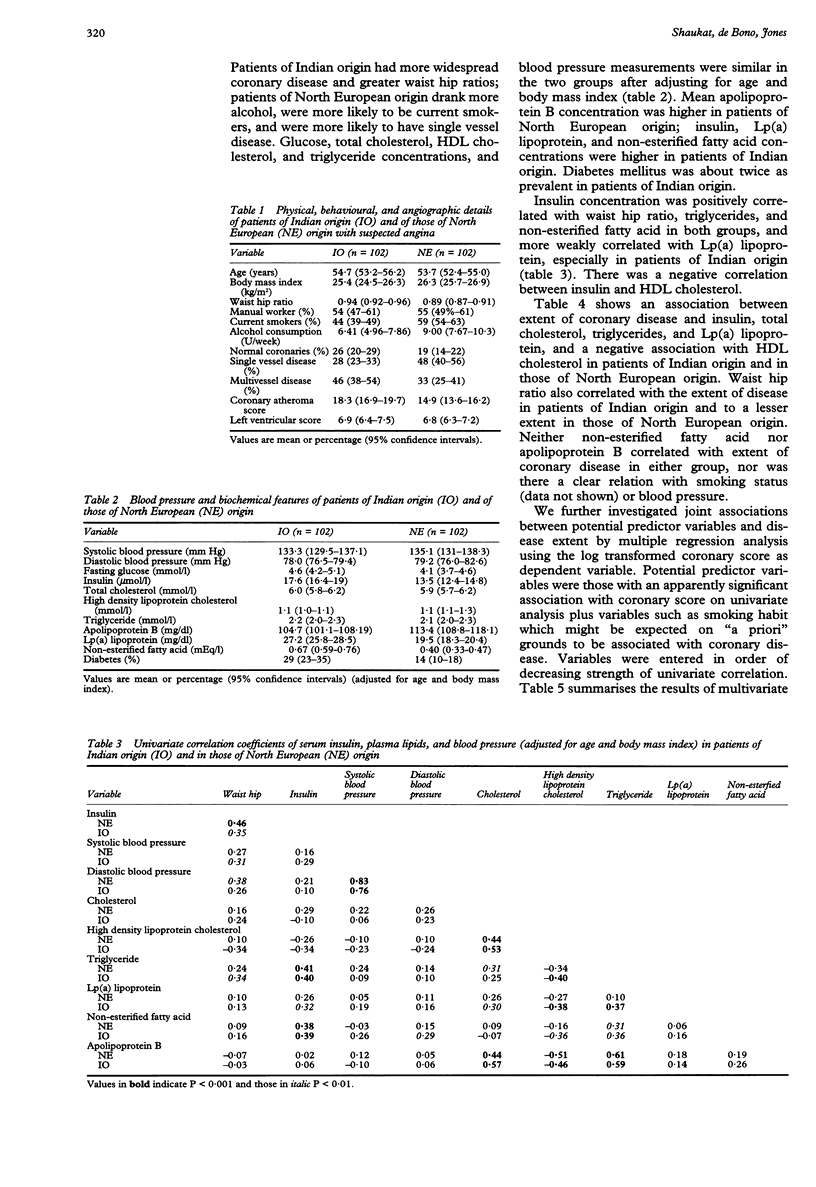

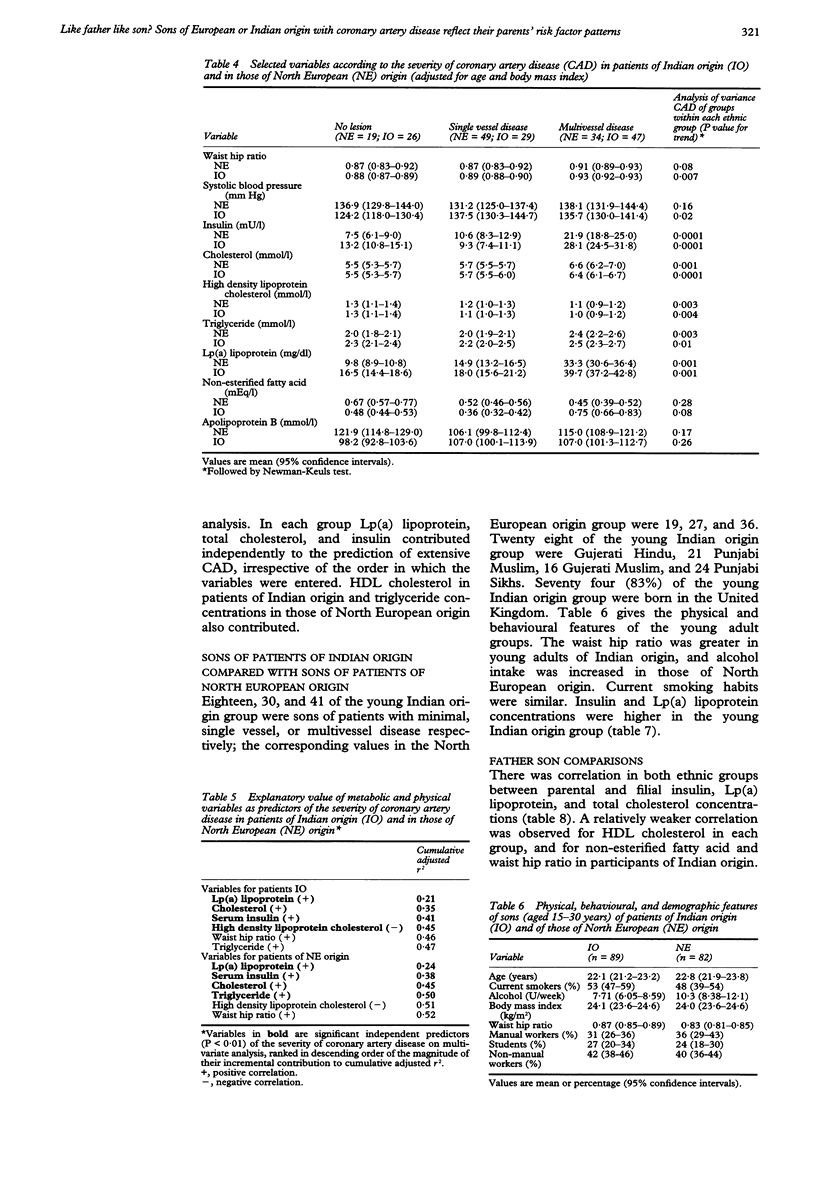

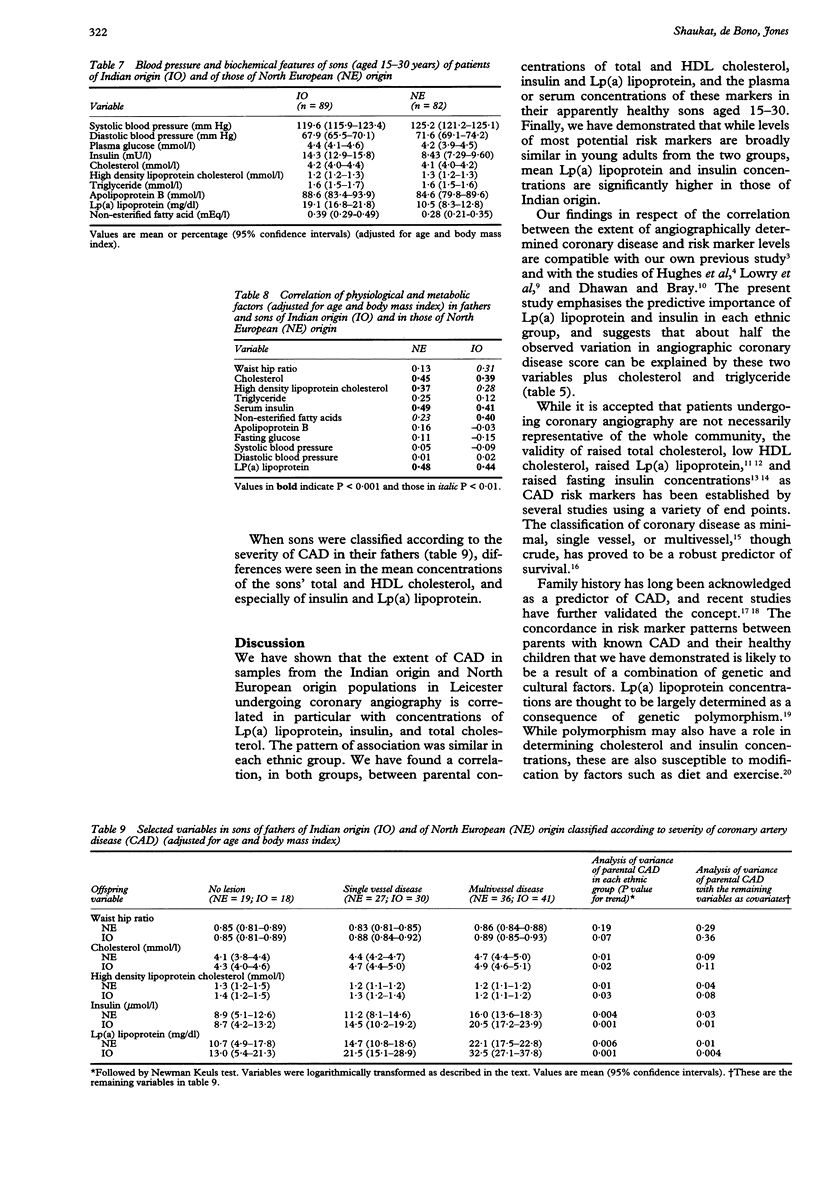

OBJECTIVE--To investigate the extent to which risk factor patterns associated with coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients of Indian origin and in those of North European origin undergoing coronary angiography for suspected angina were reflected in their apparently healthy sons aged 15-30 years. DESIGN--Prospective study in which risk markers were measured in patients of Indian origin and in matched European patients undergoing angiography and in their sons. SETTING--Patients attending a regional cardiac centre and their families. PATIENTS--102 consecutive male patients of Indian origin undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography for suspected angina and 89 of their sons aged between 15 and 30 years; 102 age matched male European patients and 82 sons. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Father son correlations for risk markers predicting the severity of parental CAD; differences in mean levels of these markers between young males of Indian origin and those of North European origin. RESULTS--Lp(a) lipoprotein, total cholesterol, and serum insulin were independent predictors of the severity of CAD in patients of Indian origin and in those of North European origin. In both groups, there was strong correlation between paternal and filial serum insulin (r = 0.41 Indian origin, r = 0.49 North European, P < 0.001), Lp(a) lipoprotein (r = 0.44 Indian origin, r = 0.48 North European, P < 0.001), and total cholesterol (r = 0.39 Indian origin, r = 0.45 North European, P < 0.001) concentrations, and the risk factor profiles of the sons were predictive of CAD severity in their fathers. Sons of patients of Indian origin had significantly higher serum insulin (Indian origin 14.3 mU/l v North European 8.4 mU/l, P = 0.002) and Lp(a) lipoprotein (Indian origin 19.1 mmol/l v North European 10.5 mmol/l, P = 0.001) concentrations than sons of patients of North European origin. CONCLUSIONS--Apparently healthy young men aged 15-30 years from either ethnic community already reflect risk marker patterns associated with coronary artery disease in their parents, both for genetically determined factors such as Lp(a) lipoprotein and environmentally influenced factors such as insulin and cholesterol. Health promotion measures aimed at reducing the prevalence of CAD should include the adolescent and young adult populations, particularly those with a family history of CAD, or who are from ethnic communities in which this diagnosis is prevalent.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adolphson J. L., Albers J. J. Comparison of two commercial nephelometric methods for apoprotein A-I and apoprotein B with standardized apoprotein A-I and B radioimmunoassays. J Lipid Res. 1989 Apr;30(4):597–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balarajan R. Ethnic differences in mortality from ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease in England and Wales. BMJ. 1991 Mar 9;302(6776):560–564. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6776.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen G. H., Guyton J. R., Attar M., Farmer J. A., Kautz J. A., Gotto A. M., Jr Association of levels of lipoprotein Lp(a), plasma lipids, and other lipoproteins with coronary artery disease documented by angiography. Circulation. 1986 Oct;74(4):758–765. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.4.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan J., Bray C. L. Relationship between angiographically assessed coronary artery disease, plasma insulin levels and lipids in Asians and Caucasians. Atherosclerosis. 1994 Jan;105(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimsdale J. E. Familial aggregation of coronary heart disease and its relation to known genetic risk factors. Am J Cardiol. 1983 Jun;51(10):1804–1804. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayna D. T., Hegele R. A., Hass P. E., Emi M., Wu L. L., Eaton D. L., Lawn R. M., Williams R. R., White R. L., Lalouel J. M. Genetic linkage between lipoprotein(a) phenotype and a DNA polymorphism in the plasminogen gene. Genomics. 1988 Oct;3(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrington P. N., Whicher J. T., Warren C., Bolton C. H., Hartog M. A comparison of methods for the immunoassay of serum apolipoprotein B in man. Clin Chim Acta. 1976 Aug 16;71(1):95–108. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(76)90280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C., Yates A. P., Davies D. Evidence for a direct action of exogenous insulin on the pancreatic islets of diabetic mice: islet response to insulin pre-incubation. Diabetologia. 1985 May;28(5):291–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00271688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes L. O., Wojciechowski A. P., Raftery E. B. Relationship between plasma cholesterol and coronary artery disease in Asians. Atherosclerosis. 1990 Jul;83(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(90)90125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto V. A., Yki-Järvinen H., DeFronzo R. A. Physical training and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1986;1(4):445–481. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610010407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry P. J., Glover D. R., Mace P. J., Littler W. A. Coronary artery disease in Asians in Birmingham. Br Heart J. 1984 Dec;52(6):610–613. doi: 10.1136/hrt.52.6.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy A. G., Woods K. L., Botha J. L. The effects of demographic shift on coronary heart disease mortality in a large migrant population at high risk. J Public Health Med. 1991 Nov;13(4):276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeigue P. M., Ferrie J. E., Pierpoint T., Marmot M. G. Association of early-onset coronary heart disease in South Asian men with glucose intolerance and hyperinsulinemia. Circulation. 1993 Jan;87(1):152–161. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeigue P. M., Shah B., Marmot M. G. Relation of central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes prevalence and cardiovascular risk in South Asians. Lancet. 1991 Feb 16;337(8738):382–386. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91164-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai A., Miyahara T., Fujimoto N., Matsuda M., Kameyama M. Lp(a) lipoprotein as a risk factor for coronary heart disease and cerebral infarction. Atherosclerosis. 1986 Feb;59(2):199–204. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(86)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfit W. L., Bruschke A. V., Sones F. M., Jr Natural history of obstructive coronary artery disease: ten-year study of 601 nonsurgical cases. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1978 Jul-Aug;21(1):53–78. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(78)80004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen A. M., Nikkilä E. A. Coronary artery disease and its risk factors in families of young men with angina pectoris and in controls. Br Heart J. 1977 Aug;39(8):875–883. doi: 10.1136/hrt.39.8.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S., Walton R. J., Clark P. M., Barker D. J., Hales C. N., Osmond C. The relation of fetal growth to plasma glucose in young men. Diabetologia. 1992 May;35(5):444–446. doi: 10.1007/BF02342441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat N., de Bono D. P., Cruickshank J. K. Clinical features, risk factors, and referral delay in British patients of Indian and European origin with angina matched for age and extent of coronary atheroma. BMJ. 1993 Sep 18;307(6906):717–718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6906.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]