Abstract

The incidence of traffic accidents in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) is high in the USA. However, the characteristics of patients, including dietary habits, differ between Japan and the USA. The present study investigated the incidence of traffic accidents in CLD patients and the clinical profiles associated with traffic accidents in Japan using a data-mining analysis. A cross-sectional study was performed and 256 subjects [148 CLD patients (CLD group) and 106 patients with other digestive diseases (disease control group)] were enrolled; 2 patients were excluded. The incidence of traffic accidents was compared between the two groups. Independent factors for traffic accidents were analyzed using logistic regression and decision-tree analyses. The incidence of traffic accidents did not differ between the CLD and disease control groups (8.8 vs. 11.3%). The results of the logistic regression analysis showed that yoghurt consumption was the only independent risk factor for traffic accidents (odds ratio, 0.37; 95% confidence interval, 0.16–0.85; P=0.0197). Similarly, the results of the decision-tree analysis showed that yoghurt consumption was the initial divergence variable. In patients who consumed yoghurt habitually, the incidence of traffic accidents was 6.6%, while that in patients who did not consume yoghurt was 16.0%. CLD was not identified as an independent factor in the logistic regression and decision-tree analyses. In conclusion, the difference in the incidence of traffic accidents in Japan between the CLD and disease control groups was insignificant. Furthermore, yoghurt consumption was an independent negative risk factor for traffic accidents in patients with digestive diseases, including CLD.

Keywords: road traffic accident, liver cirrhosis, dietary habits, nutrition, subclinical hepatic encephalopathy

Introduction

The development of antiviral treatment, anticancer therapy and endoscopic treatment for esophageal varix, along with nutritional care has significantly improved the prognosis of chronic liver disease (CLD) (1–3). Thereby, management of complications of CLD in addition to liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices is important. Infection and diabetes mellitus are major complications of CLD (2,4). In addition, cognitive dysfunction is frequently observed in patients with CLD (5–7), as ammonia and proinflammatory cytokines affect the central nervous system through the liver-brain axis (8).

Cognitive dysfunction occurs without signs of hepatic encephalopathy, and affects daily function and health-related quality of life, and causes falls in CLD patients (9,10). Additionally, cognitive dysfunction has been reported to be associated with poor driving performance (11). Disease-related traffic accident is a serious social issue worldwide (12), and the incidence of traffic accidents is high in patients with liver cirrhosis in the USA (13,14). However, traffic conditions and the characteristics of CLD patients, including age and etiology of CLD, in Japan differ from those of CLD patients in the USA. Thus, the impact of CLD on traffic accidents in Japan remains to be elucidated.

Cognitive function is regulated by various factors. Alcohol consumption, starvation, malnutrition, advanced liver cirrhosis, constipation and psychotropic medication are known risk factors for cognitive dysfunction in patients with CLD (10,12,15). By contrast, supplementation with branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) and treatment with lactulose for hyperammonemia alleviate cognitive dysfunction in patients with CLD (12,16). Furthermore, habitual consumption of coffee or yoghurt enhances attention (17–20). Although these factors are thought to affect the occurrence of traffic accidents, limited information is available on the impact of these dietary factors on traffic accidents in patients with CLD.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the incidence of traffic accidents in patients with CLD in Japan. In addition, the risk factors and the clinical profiles associated with traffic accidents were investigated.

Subjects and methods

Ethics

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in the prior approval of the Institutional Review Board of Kurume University (Kurume, Fukuoka, Japan; approval no. 12142). Written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from each subject. None of the subjects were institutionalized.

Study design

Between August 2012 and June 2015, a cross-sectional case-control study was performed to investigate the impact of CLD on the incidence of traffic accidents in Japan.

Subjects

Inclusion criteria were patients: i) With CLD (case) or other digestive diseases [disease control (disease CON)], ii) whose performance status was 0 or 1, iii) who regularly drive any type of vehicle (car, motorcycle or bicycle), and iv) who agreed with the study protocol. Exclusion criteria were patients with hepatic encephalopathy, active alcohol intake (in the 3 months before the study), epilepsy, syncope, severe hypoglycemia, severe sleep disorder, manic-depressive psychosis and dementia. Severe hypoglycemia was defined as a blood glucose level <50 mg/dl or symptoms that promptly resolve with oral carbohydrate or intravenous glucose, as previously described (21). Severe sleep disorder was defined as sleep episodes that are present daily and at times of physical activities that require mild to moderate attention, as previously described (22). According to the International Classification of Disease 10th revision, dementia was defined as a disorder with deterioration in memory and thinking, which is sufficient to impair personal activities of daily living (23).

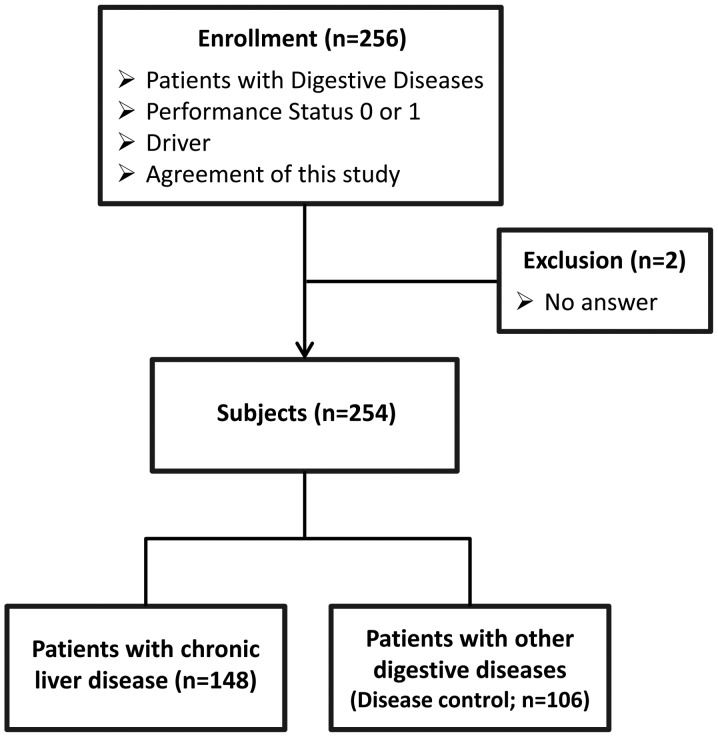

A total of 256 patients were enrolled and, of these, 2 patients were excluded as they did not provide answers to questions regarding traffic accidents (Fig. 1). In total, 254 patients were classified into the following two groups: i) The CLD group (total n=148; hepatitis C virus, n=91; hepatitis B virus, n=18; alcoholic liver disease, n=13; nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, n=4; others, n=22) and ii) the disease CON group (total n=106; pancreatic malignancy, n=20; gastric cancer, n=18; colon polyp, n=16; bile duct cancer, n=11; esophageal cancer, n=6; bile duct stone, n=6; ulcerative colitis, n=5; colitis, n=3; pancreatitis, n=2; others, n=19). The diagnoses of CLD and digestive diseases were based on the results of clinical examination, serological examination, imaging and histological examination.

Figure 1.

Study design. A total of 256 patients with digestive diseases were enrolled. Of these, 2 patients were excluded as they did not provide answers to questions regarding traffic accidents. The remaining 254 patients were classified into the chronic liver disease (CLD) group (n=148) or disease control (disease CON) group (n=106).

Clinical characteristics and lifestyle

Data regarding the clinical characteristics and lifestyle factors of the subjects, including age, gender, sleep disturbance, constipation, muscle cramp, habitual coffee consumption and habitual yoghurt consumption, were collected prior to any invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2).

Definition of habitual coffee and yoghurt consumptions

Habitual coffee consumption was defined as drinking ≥1 cup of coffee/day (>180 ml/day) (24). Habitual yoghurt consumption was defined as consuming ≥1 cup of yoghurt/day (>100 g/day) (25).

Laboratory examinations

Venous blood samples were collected in the morning after a 12-h overnight fast. Platelet count; prothrombin activity; serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine levels; and blood glucose, urea nitrogen, and ammonia levels were measured using standard clinical methods (Department of Clinical Laboratory, Kurume University Hospital). The stage of liver fibrosis was assessed by the AST-to-platelet ratio index (APRI): Serum AST level (U/l)/upper limit of normal AST (33 U/l) × 100/platelet count (×104/ml) (26). Patients with APRI values of ≤1.5 were diagnosed with chronic hepatitis, and those with APRI values >1.5 were diagnosed with liver cirrhosis (26).

Medications

Data regarding the use of psychotropic medication, BCAA-related medication or lactulose were collected from the medical records of the patients.

Erroneous stepping on the accelerator and brake, near miss of a traffic accident, and traffic accident

Among the subjects who drive a car, the experience of erroneous stepping on the accelerator and brake was investigated using a questionnaire sheet. For all the subjects, the experience of a near miss of a traffic accident and a traffic accident was investigated using a questionnaire sheet. A near miss of a traffic accident was defined as the experience for avoidance of any type of traffic accidents, including property damage. A traffic accident was defined as the experience of any type of traffic accidents, including property damage.

Statistical analysis

Non-parametric comparisons were made using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and categorical comparisons were made using Fisher's exact test. A logistic regression model was used for multivariate stepwise analysis to identify any independent variables that were associated with traffic accidents, as previously describe (27). A decision-tree algorithm was constructed to identify profiles associated with traffic accidents, as previously described (28,29).

A stratification analysis was also performed for patients with CLD. Multivariate stepwise and decision-tree analyses were performed to identify any independent variables that were associated with traffic accidents. All the statistical analyses were conducted using JMP Pro version 11.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data are expressed as number or median (range). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table I. Age, male-to-female ratio, BMI and prevalence of muscle cramp were significantly higher in the CLD group compared to the disease CON group. However, no significant difference was identified between the CLD and disease CON groups in the prevalence of sleep disturbance, constipation and use of psychotropic medication. No significant difference was apparent between the CLD group and the disease CON group in the prevalence of habitual coffee, yoghurt and alcohol consumption (Table I).

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | CLD group | Disease CON group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 148 | 106 | |

| Median age, years (range) | 71 (17–85) | 65 (24–86) | 0.0006 |

| Male/female, n | 103/45 | 60/46 | 0.0332 |

| Median body mass index, kg/m2 (range) | 23.2 (15.8–35.7) | 21.6 (15.0–34.1) | 0.0023 |

| Lifestyle, n | |||

| Sleep, hypersomnia/good/insomnia | 8/120/20 | 4/89/13 | 0.7848 |

| Constipation, yes/no | 1/147 | 6/100 | 0.0167 |

| Muscle cramp, yes/no | 71/75 | 34/72 | 0.0085 |

| Use of psychotropic medication, yes/no | 18/129 | 10/95 | 0.4980 |

| Habitual coffee consumption, yes/no | 80/68 | 69/37 | 0.0781 |

| Habitual yoghurt consumption, yes/no | 101/46 | 65/41 | 0.2223 |

| History of alcohol consumption, yes/no | 14/134 | 10/96 | 0.5848 |

| Median biochemical examinations (range) | |||

| AST, IU/l | 48 (13–693) | 24 (8–550) | <0.0001 |

| ALT, IU/l | 37 (5–473) | 20 (3–637) | <0.0001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 0.93 (0.15–18.58) | 0.74 (0.05–23.18) | 0.0019 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.53 (2.23–4.85) | 4.00 (1.7–5.04) | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.72 (0.30–8.84) | 0.71 (0.33–2.43) | 0.2002 |

| Prothrombin activity, % | 81 (21–140) | 103 (22–140) | <0.0001 |

| Platelet count, ×103/mm3 | 11.1 (3.6–40.3) | 21.6 (4.5–64.3) | <0.0001 |

| CLD-related variables | |||

| Presence of liver cirrhosis, n (yes/no) | 81/67 | N/A | N/A |

| Median APRI (range) | 1.64 (0.19–8.37) | N/A | N/A |

| Median ammonia, μg/dl (range) | 51 (15–200) | N/A | N/A |

| Use of BCAA-related medication, n (yes/no) | 54/94 | N/A | N/A |

| Use of lactulose, n (yes/no) | 16/132 | N/A | N/A |

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; N/A, not applicable; APRI, AST-to-platelet ratio index; BCAA, branched-chain amino acid; CLD group, chronic liver disease group; disease CON group, disease control group.

The results of biochemical examinations showed a significant elevation in the serum AST, ALT and total bilirubin levels in the CLD group, as compared to the levels in the disease CON group. The serum albumin level, prothrombin activity and platelet count were significantly lower in the CLD group compared to the corresponding values in the disease CON group (Table I).

In the CLD group, the prevalence of liver cirrhosis was 54.7% (81/148) and the median blood ammonia level was 51 µg/dl. Use of BCAA-related medication and lactulose was observed in 36.5% (54/148) and 10.8% (16/148) of the patients in the CLD group, respectively (Table I).

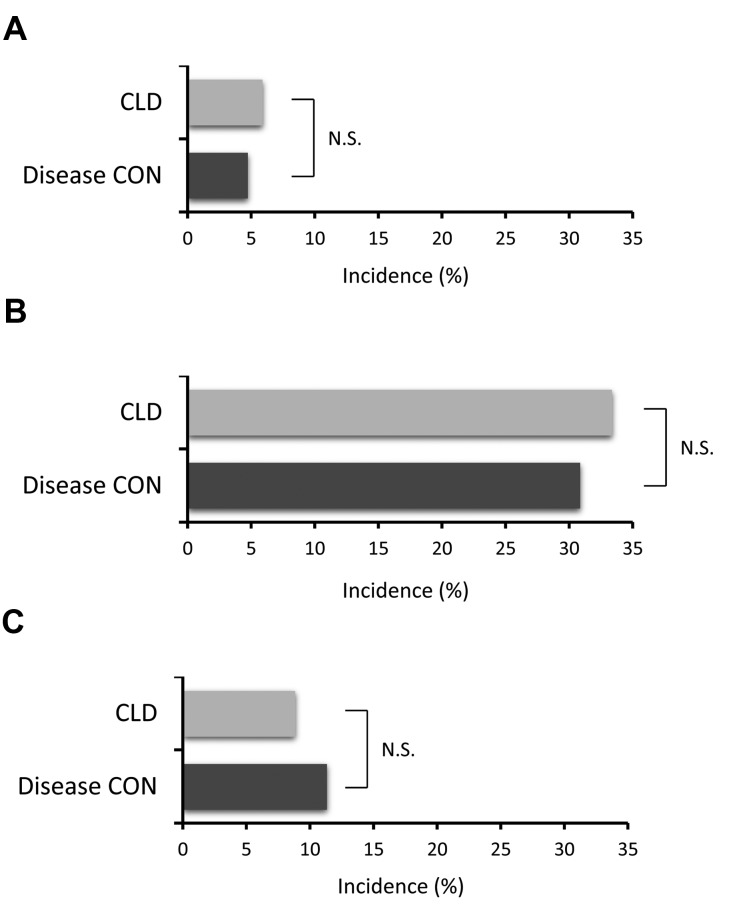

Driving status and incidence of traffic accidents

No significant difference was observed between the CLD and disease CON groups in the type of vehicle and driving time (Table II). In the CLD group, the incidence of erroneous stepping on the accelerator and brake was 5.6% (7/119; Fig. 2A), and that of a near miss of a traffic accident was 25.0% (37/111; Fig. 2B). These incidence rates did not differ from those in the disease CON group (Fig. 2A and B). The incidence of traffic accidents was 8.8% (13/148) in the CLD group, and did not differ from that in the disease CON group (Fig. 2C).

Table II.

Driving status.

| Driving variables | CLD group | Disease CON group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Car/motorcycle/bicycle, n | 124/4/20 | 89/3/14 | 0.9959 |

| Median driving time, min (range) | 60 (5–540) | 60 (10–540) | 0.6648 |

CLD group, chronic liver disease group; CON, control group.

Figure 2.

Incidence of (A) erroneous stepping on the accelerator and brake, (B) a near miss of a traffic accident and (C) traffic accidents. CLD, chronic liver disease; CON, control.

Logistic regression analysis for the incidence of traffic accidents

In a logistic regression analysis for traffic accident incidences, age, gender, sleep status, constipation, muscle cramp or use of psychotropic medication were not identified as independent factors associated with traffic accidents. Furthermore, CLD, liver cirrhosis or a history of alcohol consumption were not identified as independent factors associated with traffic accidents. Habitual yoghurt consumption was the only independent negative risk factor for traffic accidents [odds ratio (OR), 0.37; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.16–0.85; P=0.0197)] (Table III).

Table III.

Logistic regression analysis for the incidence of traffic accidents and habitual yoghurt consumption.

| Logistic regression analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

| Habitual yoghurt consumption | 0.37 | 0.16–0.85 | 0.0197 |

CI, confidence interval.

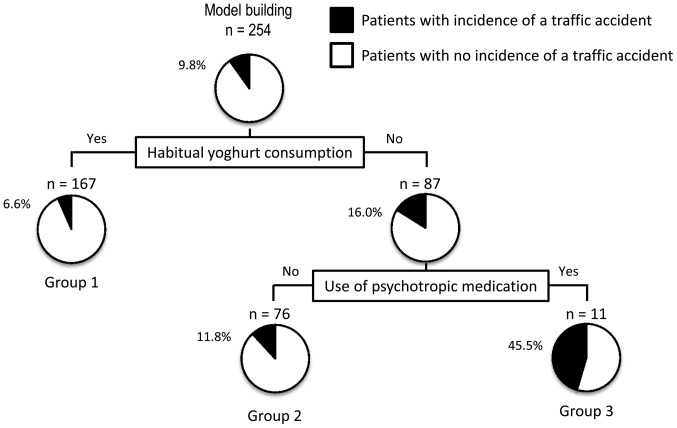

Decision-tree algorithm for traffic accidents

To clarify the profile associated with traffic accidents, a decision-tree algorithm was created using 2 divergence variables and classified the patients into three groups (Fig. 3). Habitual yoghurt consumption was the initial divergence variable. The traffic accident incidence in patients with habitual yoghurt consumption was 6.6% (group 1 in Fig. 3), whereas that in patients with no habitual yoghurt consumption was 16.0%. Among patients with no habitual yoghurt consumption, use of psychotropic medication was the variable for the second classification. Thus, in patients with no habitual yoghurt consumption and no use of psychotropic medication, the traffic accident incidence was 11.8% (group 2 in Fig. 3). By contrast, in patients with no habitual yoghurt consumption and use of psychotropic medication, the traffic accident incidence was 45.5% (group 3 in Fig. 3). In this analysis, neither CLD nor liver cirrhosis was identified as a divergence variable for the incidence of traffic accidents.

Figure 3.

A decision-tree algorithm for the incidence of traffic accidents. The subjects were classified according to the indicated variables. The pie graphs indicate the proportion of patients with no incidence of a traffic accident (white) and those with an incidence of a traffic accident (black) in each group.

Stratification analysis according to CLD

In the CLD group, the incidence of traffic accidents did not significantly differ between patients with chronic hepatitis and those with liver cirrhosis (Table IV). Furthermore, no significant difference was identified between BCAA-related medication, lactulose, HCV-infection and muscle cramp and the incidence of traffic accidents (Table IV). By contrast, the incidence of traffic accidents was significantly higher in CLD patients with a history of alcohol consumption compared to those with no history of alcohol consumption.

Table IV.

Stratification analysis according to hepatic fibrosis, branched-chain amino acids (BCAA)-related medication, lactulose use and alcohol consumption for the incidence of traffic accidents in patients with chronic liver disease.

| Traffic accidents, n | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Incidence | No incidence | P-value |

| Chronic hepatitis | 7 | 60 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 6 | 75 | 0.5154 |

| Use of BCAA-related medication | 0.4484 | ||

| Use | 6 | 48 | |

| No use | 7 | 87 | |

| Lactose | 0.7046 | ||

| Use | 1 | 15 | |

| No use | 12 | 120 | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.006 | ||

| History | 4 | 10 | |

| No history | 9 | 125 | |

In the CLD group, logistic regression and decision analyses were performed to clarify the independent factor and the profile associated with traffic accidents. In the logistic regression analysis, use of psychotropic medication was the only independent risk factor for traffic accidents (OR, 5.81; 95% CI, 1.57–20.3; P=0.0100) (Table V). In this analysis, liver cirrhosis, etiology of liver disease, blood ammonia level, use of BCAA-related medication, or lactulose use were not identified as independent factors associated with traffic accidents (Table V).

Table V.

Logistic regression analysis for the incidence of traffic accidents in patients with chronic liver disease and use of psychotropic medication.

| Logistic regression analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

| Use of psychotropic medication | 5.81 | 1.57–20.3 | 0.0100 |

CI, confidence interval.

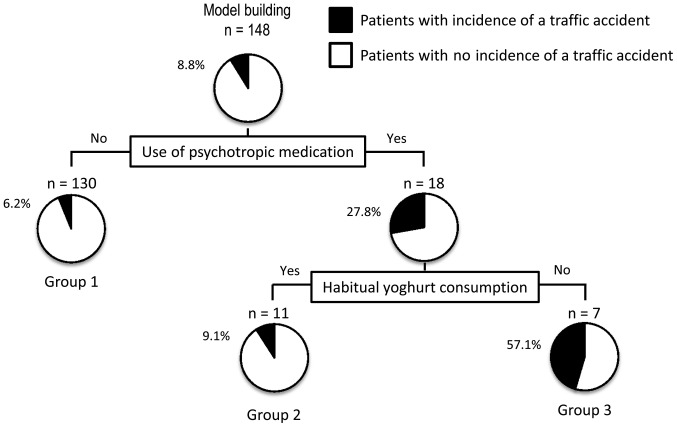

In this stratification analysis, a decision-tree algorithm was created using 2 divergence variables to classify the patients into three groups (Fig. 4). Use of psychotropic medication was the initial classification variable. In CLD patients who were not administered psychotropic medication, the traffic accident incidence was 6.2% (group 1 in Fig. 4), whereas in those who were administered psychotropic medication, the traffic accident incidence was 27.8%. Among patients who were administered psychotropic medication, habitual yoghurt consumption was the variable for the second classification. Thus, in patients who were administered psychotropic medication and habitually consumed yoghurt, the traffic accident incidence was 9.1% (group 2 in Fig. 4), whereas in patients who used psychotropic medication and did not habitually consume yoghurt, the traffic accident incidence was 57.1% (group 3 in Fig. 4). In this analysis, liver cirrhosis, etiology of liver disease, blood ammonia level, use of BCAA-related medication or lactulose use were not identified as divergence variables for the incidence of traffic accidents.

Figure 4.

A decision-tree algorithm for the incidence of traffic accidents in patients with CLD. The subjects were classified according to the indicated variables. The pie graphs indicate the proportion of patients with no incidence of a traffic accident (white) and those with an incidence of a traffic accident (black) in each group.

Discussion

In the present study, no significant difference was observed between the incidence of traffic accidents in CLD patients from that in patients with other digestive diseases. In addition, CLD was not an independent risk factor for the incidence of traffic accidents. Habitual yoghurt consumption was also found to be an independent negative risk factor for traffic accidents.

In the present study, the incidence of traffic accidents was 8.8% in CLD patients, and no significant difference was identified for this incidence and for that in patients with other digestive diseases. By contrast, as reported by Bajaj et al (14,30), 17.0% of patients with liver cirrhosis experience traffic accidents in the USA, and this incidence is significantly higher compared to that in their control group. The reason for the difference in the incidence of traffic accidents between the previous studies and the present study remains to be elucidated. In the present study, the disease CON group included patients with pancreatic malignancy and ulcerative colitis. These diseases have poor health-related quality of life, suggesting that the incidence of traffic accidents may be high due to these diseases. The incidence of traffic accidents in the area is 1.23% (41,618 accidents/3,329,884 automobiles owned in the area) according to Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in Japan (31). Although there is no data for age and physical condition in automobile owners of the area, the incidence of traffic accidents in CLD patients may be higher than that in the healthy population.

Liver cirrhosis was not identified as an independent risk factor or a divergence variable for traffic accidents in the present study. According to the previous studies, liver cirrhosis may influence the incidence of traffic accidents (14,30) and the possible explanations for the present observation are the differences in the medication for liver cirrhosis and etiology of CLD between Japan and the USA. In the present study, 50.6% of patients with liver cirrhosis were treated with BCAA-related medication. Nutritional management, including treatment with BCAA, has been reported to alleviate minimal hepatic encephalopathy 5, which is a neurocognitive dysfunction associated with traffic accidents (15,32). In addition, alcohol consumption was observed in 24.6% of patients with liver cirrhosis in a previous study (14). By contrast, alcohol consumption was observed in 9.5% of the subjects in the present study. Alcohol consumption is the main factor in traffic accident fatalities (33,34). In the present study, a history of alcohol consumption in CLD patients was significantly associated with the incidence of traffic accident; this finding suggests that the incidence of traffic accident is associated with the alcohol consumption.

The present study examined the current factor(s) associated with the incidence of traffic accidents in Japan, and found that habitual yoghurt consumption was an independent negative risk factor for traffic accidents, according to the results of the logistic regression analysis. Similarly, habitual yoghurt consumption was the initial divergence variable in the decision-tree algorithm for traffic accidents. Furthermore, in CLD patients, habitual yoghurt consumption was the second divergence variable followed by the use of psychotropic medication in the decision-tree algorithm for traffic accidents. A decision tree analysis was also performed for near-miss of a traffic accident. However, as opposed to clinical profile of traffic accidents, gender is the initial divergence variable and habitual yoghurt consumption was not identified as a variable associated with near-miss of a traffic accident (data not shown). Patients with experience of near-miss of a traffic accident could avoid traffic accidents. This data also implies that habitual yoghurt consumption is a specific factor associated with the incidence of traffic accidents.

A causal association between habitual yoghurt consumption and traffic accidents could not be examined in this study, and none of the previous studies have reported an association between yoghurt consumption and traffic accidents. However, the impact of the gut-brain axis on human health and disease is apparent. Yoghurt consumption is known to affect the activity of brain regions that control the central processing of emotion and sensation (20). In addition, yogurt supplementation is known to alleviate minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis (35). Gut microbiota regulates circulating tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ levels through mucosal immune mechanisms (36,37). Gut microbiota also regulates the metabolism of tryptophan and short-chain fatty acids (38,39). These microbiota-associated factors are known to alter hippocampal expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (37), a modulator of cognitive function (40). In addition to this mechanism, gut microbiota influences the brain function through neuroactive substances and enterochromaffin cell-mediated vagal activation (39). Taken together, the previous findings and the present results suggest that habitual yoghurt consumption inhibits cognitive dysfunctions and thereby has a beneficial role in traffic accidents.

Various types of yoghurts are now commercially available. Although the present study did not evaluate the type of probiotic bacteria in yoghurt, Bravo et al (41) reported that the Lactobacillus strain directly regulates brain function via reduction of GABA (Aα2) mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Certain Japanese diets and supplementations contain the Lactobacillus species, including Miso, a Japanese traditional fermented soybean paste, and lactic acid supplementation. Thus, a dietary survey may provide further beneficial information for prevention of traffic accidents.

In conclusion, no significant difference was identified in the incidence of traffic accidents between CLD patients and patients with digestive diseases. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that habitual yoghurt consumption was an independent negative risk factor for traffic accidents in patients with digestive diseases and those with CLD.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CLD

chronic liver disease

- BCAA

branched-chain amino acids

- CON

control

- BMI

body mass index

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- APRI

AST to platelet ratio index

References

- 1.Shiratori Y, Shiina S, Teratani T, Imamura M, Obi S, Sato S, Koike Y, Yoshida H, Omata M. Interferon therapy after tumor ablation improves prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis C virus. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:299–306. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawaguchi T, Shiraishi K, Ito T, Suzuki K, Koreeda C, Ohtake T, Iwasa M, Tokumoto Y, Endo R, Kawamura NH, et al. Branched-chain amino acids prevent hepatocarcinogenesis and prolong survival of patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1012–1018.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minami T, Tateishi R, Shiina S, Nakagomi R, Kondo M, Fujiwara N, Mikami S, Sato M, Uchino K, Enooku K, et al. Comparison of improved prognosis between hepatitis B- and hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2015;45:E99–E107. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawaguchi T, Izumi N, Charlton MR, Sata M. Branched-chain amino acids as pharmacological nutrients in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1002/hep.24412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato A, Tanaka H, Kawaguchi T, Kanazawa H, Iwasa M, Sakaida I, Moriwaki H, et al. Nutritional management contributes to improvement in minimal hepatic encephalopathy and quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis: A preliminary, prospective, open-label study. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:452–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawaguchi T, Taniguchi E, Sata M. Effects of oral branched-chain amino acids on hepatic encephalopathy and outcome in patients with liver cirrhosis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013;28:580–588. doi: 10.1177/0884533613496432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kappus MR, Bajaj JS. Covert hepatic encephalopathy: Not as minimal as you might think. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butterworth RF. The liver-brain axis in liver failure: Neuroinflammation and encephalopathy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:522–528. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel AV, Wade JB, Thacker LR, Sterling RK, Siddiqui MS, Stravitz RT, et al. Cognitive reserve is a determinant of health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis, independent of covert hepatic encephalopathy and model for end-stage liver disease score. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:987–991. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soriano G, Román E, Córdoba J, Torrens M, Poca M, Torras X, Villanueva C, Gich IJ, Vargas V, Guarner C. Cognitive dysfunction in cirrhosis is associated with falls: A prospective study. Hepatology. 2012;55:1922–1930. doi: 10.1002/hep.25554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, Hammeke TA. Patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy have poor insight into their driving skills. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1135–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.025. quiz 1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawaguchi T, Taniguchi E, Sata M. Motor vehicle accidents: How should cirrhotic patients be managed? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2597–2599. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i21.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patidar KR, Bajaj JS. Covert and overt hepatic encephalopathy: Diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2048–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Schubert CM, Hafeezullah M, Franco J, Varma RR, Gibson DP, Hoffmann RG, Stravitz RT, Heuman DM, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy is associated with motor vehicle crashes: The reality beyond the driving test. Hepatology. 2009;50:1175–1183. doi: 10.1002/hep.23128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bajaj JS. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy matters in daily life. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3609–3615. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kachaamy T, Bajaj JS. Diet and cognition in chronic liver disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:174–179. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283409c25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Abbadi NH, Dao MC, Meydani SN. Yogurt: Role in healthy and active aging. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(Suppl 5):1263S–1270S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.073957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikic PM, Andric BR, Stojimirovic BB, Trbojevic-Stankovic J, Bukumiric Z. Habitual coffee consumption enhances attention and vigilance in hemodialysis patients. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:707460. doi: 10.1155/2014/707460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Barulli MR, Bonfiglio C, Guerra V, Osella A, Seripa D, Sabbà C, Pilotto A, Logroscino G. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and prevention of late-life cognitive decline and dementia: A systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:313–328. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0563-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, Jiang Z, Stains J, Ebrat B, Guyonnet D, Legrain-Raspaud S, Trotin B, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1394–1401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. 1401.e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonds DE, Kurashige EM, Bergenstal R, Brillon D, Domanski M, Felicetta JV, et al. ACCORD Study Group: Severe hypoglycemia monitoring and risk management procedures in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(12A):80i–89i. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Sleep Medicine: International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Darien, IL: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization (WHO): ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. WHO, Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima K, Hirose K, Ebata M, Morita K, Munakata H. Association between habitual coffee consumption and normal or increased estimated glomerular filtration rate in apparently healthy adults. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:149–152. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sayón-Orea C, Bes-Rastrollo M, Martí A, Pimenta AM, Martín-Calvo N, Martínez-González MA. Association between yogurt consumption and the risk of metabolic syndrome over 6 years in the SUN study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:170. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1518-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taniguchi E, Kawaguchi T, Sakata M, Itou M, Oriishi T, Sata M. Lipid profile is associated with the incidence of cognitive dysfunction in viral cirrhotic patients: A data-mining analysis. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:418–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otsuka M, Uchida Y, Kawaguchi T, Taniguchi E, Kawaguchi A, Kitani S, Itou M, Oriishi T, Kakuma T, Tanaka S, et al. Fish to meat intake ratio and cooking oils are associated with hepatitis C virus carriers with persistently normal alanine aminotransferase levels. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:982–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taniguchi E, Kawaguchi T, Otsuka M, Uchida Y, Nagamatsu A, Itou M, Oriishi T, Ishii K, Imanaga M, Suetsugu T, et al. Nutritional assessments for ordinary medical care in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:192–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, Saeian K. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: A vehicle for accidents and traffic violations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1903–1909. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.http://www.mlit.go.jp/road/road/traffic/sesaku/data.html. [2015];Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in Japan: Traffic accident data collection. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wein C, Koch H, Popp B, Oehler G, Schauder P. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy impairs fitness to drive. Hepatology. 2004;39:739–745. doi: 10.1002/hep.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynaud M, Le Breton P, Gilot B, Vervialle F, Falissard B. Alcohol is the main factor in excess traffic accident fatalities in France. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1833–1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gómez-Restrepo C, Gómez-García MJ, Naranjo S, Rondón MA, Acosta-Hernández AL. Alcohol consumption as an incremental factor in health care costs for traffic accident victims: Evidence in a medium sized Colombian city. Accid Anal Prev. 2014;73:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Christensen KM, Hafeezullah M, et al. Probiotic yogurt for the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1707–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbanska AM, Paul A, Bhathena J, Prakash S. Suppression of tumorigenesis: modulation of inflammatory cytokines by oral administration of microencapsulated probiotic yogurt formulation. Int J Inflam. 2010;2010:894972. doi: 10.4061/2010/894972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reigstad CS, Salmonson CE, Rainey JF, III, Szurszewski JH, Linden DR, et al. Gut microbes promote colonic serotonin production through an effect of short-chain fatty acids on enterochromaffin cells. FASEB J. 2015;29:1395–1403. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-259598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zelante T, Iannitti RG, Cunha C, De Luca A, Giovannini G, Pieraccini G, Zecchi R, D'Angelo C, Massi-Benedetti C, Fallarino F, et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity. 2013;39:372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaynman S, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Hippocampal BDNF mediates the efficacy of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2580–2590. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]