Abstract

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a common, locally invasive epithelial malignancy of skin and its appendages. Every year, close to 10 million people get diagnosed with BCC worldwide. While the histology of this lesion is mostly predictable, some of the rare histological variants such as cystic, adenoid, morpheaform, infundibulocystic, pigmented and miscellaneous variants (clear-cell, signet ring cell, granular, giant cell, adamantanoid, schwannoid) are even rarer, accounting for <10% of all BCC's. Adenoid BCC (ADBCC) is a very rare histopathological variant with reported incidence of only approximately 1.3%. The clinical appearance of this lesion can be a pigmented or non-pigmented nodule or ulcer without predilection for any particular site. We share a case report of ADBCC, a rare histological variant of BCC that showed interesting features not only histologically but also by clinically mimicking a benign lesion.

Background

Adenoid basal cell carcinoma (ADBCC) is one of the rare, differentiated and low-grade malignancies usually reported at various sites including the axillae, back, leg, inner canthus of the eye, chin, forehead and rarely even the cervix and prostate. The rarity of this lesion can be ascertained by the paucity of material available in the literature. An awareness of its histology helps in making an accurate diagnosis as it often mimics cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (CACC) and primary cribriform apocrine carcinoma (CAC), which are also rare skin lesions. Making the correct diagnosis is crucial because of the prognostic differences of these conditions. We report a case of this rare lesion, which was initially diagnosed as benign based on the clinical history and appearance, but later, on histopathological assessment, surprisingly turned out to be malignant. By writing up this case we hope to contribute further details about ADBCC, in particular the rare facet that showed a benign clinical course and the challenging histopathological diagnosis, which reinforces the need for the differentiation from its mimickers.

Case presentation

A 32-year-old woman presented with a growth near the lateral canthus of her left eye, which had been slowly evolving for 8 years. She also gave a history of pigmentation beside the growth since birth. Initially, the growth had been small, but it had gradually increased to the present size. The patient had no significant medical history and no family member reported any such growth. On skin examination, an irregular brownish-black pigmented growth was seen arising from the skin around the lateral canthus of the left eye, measuring approximately 1.5 cm×1.0 cm in diameter (figure 1). On palpation, the growth was non-tender, non-fluctuant and firm in consistency, with no noticeable discharge. The pigmentation around the growth was in the form of an irregularly shaped melanotic patch arising approximately 1.5 cm above the lateral canthus of the left eye, measuring approximately 1.5 cm×3.5 cm, and extending posteriorly to end 3 cm short of the tragus of the left ear. As it was an apparently benign looking soft tissue lesion, the patient was advised excisional biopsy to confirm the histopathological diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Clinical picture shows irregular pigmented growth along with a melanotic patch near the lateral canthus of the left eye.

All the required preoperative investigations were carried out and opinion regarding proper medical fitness was obtained from the physician. First the extension of the lesion was marked using Carmalin indigo dye (figure 2). Excisional biopsy was carried out under general anaesthesia (figure 3) and the entire specimen obtained; it was then fixed, processed, stained with H&E staining procedure and observed under a light microscope. Microscopically, the sections showed groups of proliferating epithelial cells in the form of islands infiltrating into the connective tissue. The lesional tissue was arranged in a lobular pattern, showing communication with the epidermis along with secondary appendages of the skin (figure 4). The epithelial cells were basaloid, showing peripheral palisading with pleomorphism and mitotic activity. The basaloid cells showed arrangement in a cribriform pattern along with presence of mucin in the ductal spaces (figure 5). Melanin deposition was also seen in these islands (figure 5). Correlating clinically and radiologically, the histopathological features were suggestive of an adenoid pattern of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Postoperative 1-month, 3-month and 6-month, and 1–2 year follow-up was uneventful as seen in (figure 6).

Figure 2.

Clinical picture shows presurgical marking of the margins, using Carmalin indigo dye.

Figure 3.

Clinical picture shows excision of the lesion in toto.

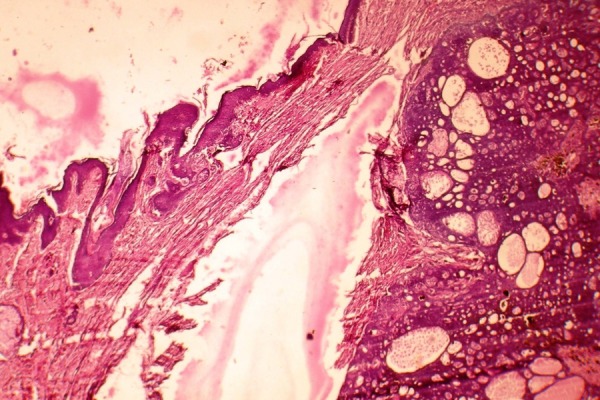

Figure 4.

Microscopic picture showing epidermis, secondary appendages and lesional tissue arranged in a lobular pattern (H&E stain, ×10 magnification).

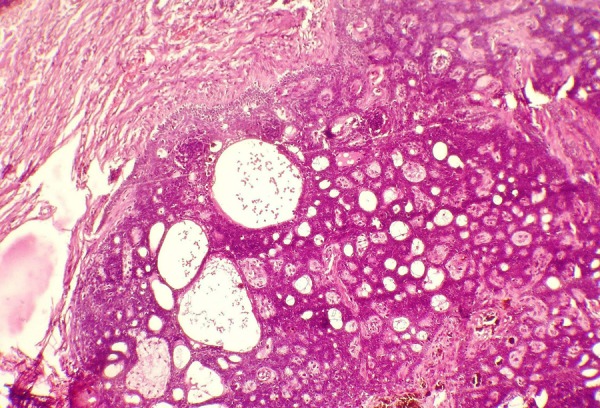

Figure 5.

Microscopic picture showing melanin deposition within lesional tissue and cribriform arrangement of basaloid cells along with mucin-filled ductal spaces (H&E stain, ×20 magnification).

Figure 6.

Clinical picture showing postoperative healed site after excision of the lesion.

Investigations

Haematological examination (haemoglobin 13.5 g, bleeding time 4 min, clotting time 3 min, random blood sugar 135 mg/dL)

Excisional biopsy

Immunohistochemical staining of cytokeratin 7 (CK 7), S-100, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

Lateral cephalogram

As part of preoperative assessment, haematological investigations were carried out, which were within normal parameters. An excisional biopsy was taken under general anaesthesia and the tissue sent for histopathological examination.

On gross examination, the specimen was irregular in shape, approximately 1.5 cm at maximum diameter, brownish-black in colour and firm in consistency. The overlying surface was smooth with focal ulceration. There was no discharge apparent.

Finally, to rule out any other lesion that may have been mimicking ADBCC, supplementary immunohistochemistry was carried out.

A lateral cephalogram of the left side was performed, which did not reveal involvement of the underlying bones (figure 7).

Figure 7.

Lateral cephalogram reveals no involvement of underlying bone.

Differential diagnosis

Clinical differential diagnosis

On the basis of clinical appearance, the differential diagnosis includes the lesions cited in table 1.1 2

Table 1.

Clinical differential diagnosis

| Pathological lesion | Clinical manifestation |

|---|---|

| Pigmented naevus |

|

| Melanoma |

|

| Pigmented basal cell carcinoma |

|

| Pigmented seborrhoeic keratosis |

|

To differentiate among these lesions histopathological investigation was carried out.

Histopathological diagnosis

Microscopic examination showed the presence of atypical cells invading into connective tissue, which excluded the possibility of a benign lesion but suggested malignancy instead.

However, the presence of islands of basaloid cells excluded the possibility of Melanoma and nudged the diagnosis towards BCC.

The presence of mucin-filled ductal spaces along with cribriform arrangement of basaloid cells implied the diagnosis of adenoid variant of BCC which is a rare variant of BCC.

Supplementary immunohistochemical analysis

CACC is a rare malignant neoplasm of the salivary gland that arises directly in the skin and shows a histopathological picture similar to that of ADBCC. Immunohistochemical analysis needs to be conducted to check for the expression of certain markers specific to CACC in order to differentiate these two lesions. The various markers suggesting a tumour of salivary gland origin are given in table 2.3 4

The expression of all the above markers was found negative, which excluded the possibility of CACC and confirmed the diagnosis of ADBCC.

BerEp4 expression is positive in nuclear and cytoplasmic staining of normal adnexal epithelium and in a number of cutaneous tumours with adnexal differentiation. BerEp4 was first established as a helpful marker for distinguishing cutaneous BCC from other tumours and has also proven useful in the identification of BCC masked by inflammation. Another marker that can be effectively used in differentiating various subtypes of BCC is CK 17. The positive staining with this marker can be reliably used to determine the adequacy of surgical margins of BCC. However, neither of the expressions of these markers were studied in this particular case.

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical marker positivity in salivary gland cells

| Immunohistochemical marker | Positivity in salivary gland parenchymal cells |

|---|---|

| EMA | Ductal and acinar cell marker; apical staining pattern |

| CEA | Ductal and acinar cell marker |

| S-100 | Myoepithelial cell marker |

| Cytokeratin 7 | Strong positivity with luminal cells while less staining with acinar, basal and myoepithelial cells |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen.

Treatment

The lesion was, surprisingly, confirmed to be malignant in nature, which was in stark contrast to its clinical behaviour and appearance. The treatment of ADBCC is excision or removal of the lesion to avoid further extension and deeper penetration, along with regular follow-up to check for recurrence and postsurgical complications. The entire lesion was removed during the excisional biopsy and, for that, a V-Y plasty and Z plasty were performed with split skin graft under general anaesthesia.

Outcome and follow-up

Follow-up of this patient was very important to check for recurrence. Postoperatively, the patient recovered well, and the surgical site healed uneventfully with no signs of persistent neurosensory deficit and no other complications (figure 6). Recall check-ups were carried out at regular intervals of 3 months for a 2-year duration, to check for recurrence of the lesion. There was no recurrence and the patient was asymptomatic at the end of the 2-year follow-up.

Discussion

Initially described as ‘ulcus rodens’ by Jacob, in 1827, the current terminology of BCC was proposed by Krompecher in 1903.5 BCC represents approximately 70% of all malignant diseases of the skin, close to 75% of non-melanoma skin cancers and around 65% of epithelial tumours.6–8 Gross differences are noted in the percentage of BCC in blacks (1–2%) and Asians (2–4%) compared with in Caucasians (70–80%).9 10 Although the incidence of BCC is lower in India than in the Western world, the absolute number of cases may be significant due to this country's large population. However, because of the lack of clinical studies with statistical analysis, the existing literature on BCC is scant in India; also, with this population's considerable melanin pigmentation, which protects from sunlight, BCC is less seen in India.11

The prevalence of BCC increases after the fourth decade of life, reaching its peak incidence at around the sixth decade. Males are much more commonly affected than females.8 The site predilection is almost exclusively on sun-exposed and hair bearing skin, especially of the face.12 A vast majority of the lesions (80%) are found on the head and neck with a clinical presentation that varies from a nodular lesion or erythaematous plaque to an ulcerated destructive lesion (rodent ulcer).13 While considering the histology, BCC can be divided into two classes, undifferentiated and differentiated. The differentiated type may be further subdivided into a circumscribed and infiltrative type, depending on the structure the cells differentiate into. The variants that show a differentiation towards hair structures are called keratotic BCCs, while those that differentiate into sebaceous glands are called BCC with sebaceous differentiation. Another form that shows differentiation into tubular glands is called ADBCC.14 In a recent study, the distribution of morphological subtypes of BCC was reported as 49% for nodular, 29% for mixed patterns, 13% for infiltrating, 7% for adenoid, 3% for micronodular, 1% for superficial and 1% for basosquamous, of the 103 lesions.15 In our case, the lesion occurred on the lateral canthus of the left eye region in a 32-year-old woman.

ADBCC is a rare histopathological type of BCC that shows tubular differentiation histologically, while not showing any specific site predilection clinically. Histopathology of this rare variant shows small uniform cells with peripheral palisading of the nucleus arranged in nests and cords with intertwining strands and sometimes radially around islands of connective tissue, resulting in a tumour with a lace-like pattern. An eosinophilic substance that may be colloidal in nature or amorphous granular material is sometimes seen within the lumen of the tubular structures. The true nature of this material and the secretory activity of the cells lining the lumina cannot be delineated even using histochemical methods.8

Other rare lesions that may present with similar histopathological features are trichoadenoma and CACC. Trichoadenoma is a rare solitary tumour that varies in size from 3–15 mm in diameter, and usually presents as a nodular lesion that commonly occurs on the face and buttocks. An ulcerated variant may clinically mimic BCC. Microscopically, numerous horn cysts are present throughout the dermis, and are often surrounded by eosinophilic cells. Certain cases also show a single layer of flattened granular cells interpolated between the horn cysts and surrounding eosinophilic cells.14

CACC is another rare lesion that commonly affects middle-aged and elderly individuals. Excluding the external auditory canal, the most common site of occurrence is the scalp, which accounts for almost 40% of all cases. Some other sites that may get affected by this lesion are the chest, abdomen, back, eyelid and perineum. Commonly, the lesion presents as a firm, slowly growing, ill-defined nodule that may present with symptoms including tenderness, pruritus and secondary alopecia; however, it may sometimes be asymptomatic.16 Histological features of this lesion are characterised by basaloid cells populated in the mid to deep dermis. The cells are arranged in cords and islands forming tubular structures and cribriform patterns that occasionally do not show a connection to the overlying epidermis or adnexal structures. At times, the lesion may also show cystic spaces containing mucinous material that stains positively for hyaluronic acid. The lumina of the tubular structures and the surrounding stroma may contain mucin or eosinophilic necrotic cells. True lumina are surrounded by prominent basement membrane material that is periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant.17 18

The general clinical behaviour of BCCs is generally favourable but, occasionally, lesions may grow aggressively and infiltrate into the surrounding structures.19 Infiltrative and micronodular variants are considered more aggressive due to the higher recurrence rate, which may in part be attributed to incomplete excision.20 Surgery is the most preferred treatment option for BCC. Other options may include topical 5% imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, curettage, cryotherapy and electrodesiccation.21 22

Patient's perspective.

I came to the hospital because of an aesthetically displeasing swelling on the eyelid for 2 years. After being operated on I am all right and the swelling has completely subsided.

Learning points.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is an established malignancy of the skin and its appendages that is diagnosed clinically by certain of its established clinical features. The lesion mimics a benign lesion, which is a rare phenomenon, made dangerous by the false sense of security it may afford the clinician as well as the patient.

Histologically, BCC has certain established variants. Adenoid BCC is a rare variant accounting for only 1.3% of the total cases. A perusal of the literature does not reveal much information about this particular variant.

Adenoid BCC can have a few unique features, such as a large sized lesion and tendency to involve unexposed parts such as the back and axilla.

Adenoid BCC needs to be differentiated from cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma since the prognosis and outcome of these lesions differ greatly.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their special thanks to the non-teaching staff of the Department of Oral Pathology at Yenepoya Dental College and College of Dental Science, Amargadh (Bhavnagar), India.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Alawi F. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity: an update. Dent Clin North Am 2013;57:699–710. 10.1016/j.cden.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kauzman A, Pavone M, Blanas N et al. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity: review, differential diagnosis, and case presentation. J Can Dent Assoc 2004;70:682–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagao T, Sato E, Inoue R et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of salivary gland tumors: application for surgical pathology practice. Acta Histochem Cytochem 2012;45:269–82. 10.1267/ahc.12019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namboodiripad PC. A review: immunohistochemical markers for malignant salivary gland tumors. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2014;4:127–34. 10.1016/j.jobcr.2014.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abulafia J. Epiteliomas cutaneos ensayo de classificacion histogenetica. An Bras Dermatol 1963;38:14–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panda S. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in India: current scenario. Indian J Dermatol 2010;55:373–8. 10.4103/0019-5154.74551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samarasinghe V, Madan V. Nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2012;5:3–10. 10.4103/0974-2077.94323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tambe SA, Ghate SS, Jerajani HR. Adenoid type of basal cell carcinoma: rare histopathological variant at an unusual location. Indian J Dermatol 2013;58:159 10.4103/0019-5154.108080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asuquo M, Nwagbara V, Omotos J. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: clinical pattern and challenges of treatment. Eur J Plast Surg 2011;34:459–64. 10.1007/s00238-011-0555-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs 2009;21:170–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deo SV, Hazarika S, Shukla NK et al. Surgical management of skin cancers: experience from a regional cancer centre in north India. Indian J Cancer 2005;42:145–50. 10.4103/0019-509X.17059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betti R, Bruscagin C, Inselvini E et al. Basal cell carcinomas of covered and unusual sites of the body. Int J Dermatol 1997;36:503–5. 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jetley S, Jairajpuri ZS, Rana S et al. Adenoid basal cell carcinoma and its mimics. Indian J Dermatol 2013;58:244 10.4103/0019-5154.110874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elder D, Elenitsas R, Johnson B et al. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 10th edn Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott William & Wilkins, 2009:830p. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koyuncuer A. Histopathological evaluation of non-melanoma skin cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2014;12:159 10.1186/1477-7819-12-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Hinshaw M, Longley B et al. Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma with perineural invasion treated by Mohs micrographic surgery—a case report with literature review. J Oncol 2010;2010:469049 10.1155/2010/469049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Headington JT, Teears R, Niederhuber JE et al. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of skin. Arch Dermatol 1978;114:421–4. 10.1001/archderm.1978.01640150057018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper PH, Adelson GJ, Holthaus WH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 1984;120:774–7. 10.1001/archderm.1984.01650420084023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rippey JJ. Why classify basal cell carcinomas? Histopathology 1998;32:393–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrett TL, Smith KJ, Hodge JJ et al. Immunohistochemical nuclear staining for p53, PCNA, and Ki-67 in different histologic variants of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37:430–7. 10.1016/S0190-9622(97)70145-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Love WE, Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Topical imiquimod or fluorouracil therapy for basal and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol 2009;145:1431–8. 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman B. Scientific rationale: combining imiquimod and surgical treatments for basal cell carcinomas. J Drugs Dermatol 2008;7(Suppl 1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]