Abstract

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) is a rare, aggressive type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma that is characterised by extranodal disease, with infiltration and proliferation of malignant T-cells within the liver, spleen and bone marrow. The authors report the case of a young immunocompetent man, who was admitted to the hospital with a history of prolonged, unexplained fever, fatigue and weight loss. Initial blood work showed mild pancytopaenia and imaging studies revealed hepatosplenomegaly. The diagnosis was challenging, initially mimicking infectious disease, and it required an extensive investigation that ultimately revealed the characteristic clinical, histopathological and cytogenetic features of HSTCL. The clinical course was aggressive, and despite multiagent chemotherapy, the patient died 4 months after the diagnosis. This case highlights the difficulty of diagnosing HSTCL and the importance of considering it in a differential diagnosis of hepatosplenomegaly in young men who present with constitutional symptoms and no lymphadenopathy.

Background

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) is a rare, aggressive T-cell lymphoma that accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas. It is characterised by hepatosplenic and bone marrow sinusoidal infiltration of cytotoxic T-cells, usually of γ-δ T-cell receptor type. HSTCL is more common among young men and occurs more frequently in immunocompromised patients, especially those receiving long-term immunosuppressive therapy.

The majority of patients have liver, spleen and bone marrow involvement at presentation. As a result, they tend to be anaemic and jaundiced, and have prominent hepatosplenomegaly, with no or minimal lymphadenopathy, and with constitutional or ‘B’ symptoms. The predominant laboratory findings include pancytopaenia and abnormal liver chemistry with elevated alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase.

The diagnosis is usually established from the combination of clinical findings, histological features and immunophenotypic analysis from biopsy specimens, although cytogenetic and molecular studies are occasionally needed.

HSTCL exhibits a very aggressive clinical course with a poor response to currently available therapies, and a median overall survival of 11 months.

In this case report, we highlight the clinicopathological features of HSTCL and emphasise the importance of considering diagnosis of this rare T-cell neoplasm in patients presenting with hepatosplenomegaly, B symptoms and no lymphadenopathy.

Case presentation

A young, previously healthy man presented to the emergency department, with a 6-week history of fever, fatigue and non-quantified weight loss. He denied close contact with animals, recent foreign travel and eating raw meat or drinking unpasteurised milk. He had no history of drug ingestion including supplements or illicit drugs, alcohol consumption or high-risk behaviour. His family medical history was irrelevant. On physical examination, he was febrile (40.2°C) and tachycardic (125 bpm), with palpable tender spleen, 3 cm below the left costal margin, in the absence of hepatomegaly and peripheral lymphadenopathy.

Investigations

Initial laboratory work revealed pancytopaenia (haemoglobin 11.8 g/dL, white cell count 2.2×109/L with 11% activated lymphoid cells, platelet count 98×109/L) and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate at 51 mm/h. His prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time were prolonged (56% and 19.2 s, respectively). C reactive protein level was increased at 14.6 mg/dL, with normal procalcitonin level of 0.23 ng/mL. Lactic dehydrogenase was slightly elevated 268 U/L, whereas renal and liver function tests were within normal limits.

Serology tests for mycoplasma; brucella; legionella; Q fever; cytomegalovirus; hepatitis A, B and C; and parvovirus B19 were all negative. Infectious Mononucleosis, Rapid Test, Serum (MONOS) was negative, but antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen were positive, suggesting previous infection. Screening tests for HIV, leishmaniasis, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, and common metabolic and autoimmune disorders were negative, as well as the rest of the blood, urine and stool cultural examinations.

Echocardiography showed normal ventricular function and no valvular abnormalities. A bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed but the results, including multiple cultures for different infectious diseases, were inconclusive and did not yield a diagnosis. Abdominal CT scan revealed liver and spleen within the upper limits of normal; there were no enlarged lymph nodes and no other significant alterations.

Presuming a bacterial infectious disease, a broad-spectrum antibiotic was initiated with a rapid and substantial improvement of the patient's condition during the next few days. His fever subsided and blood counts rose, and he was discharged from the hospital after 10 days with normal blood tests.

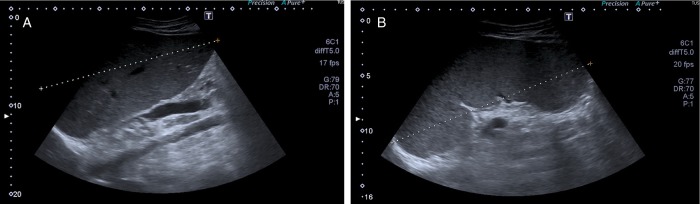

Four weeks later, the patient developed recurrent fever, malaise and progressive abdominal distension with peripheral oedema. He was readmitted to the hospital and his laboratory studies showed pancytopaenia (haemoglobin 8.6 g/dL, white cell count 2.3×109/L and platelet count 109×109/L), hypoalbuminaemia of 2.7 g/dL and elevated liver function tests at three to four times the normal values, with hyperbilirubinaemia of 3.3 mg/dL; septic work up was negative. Abdominal ultrasound (US) scan showed hepatosplenomegaly that was absent on the US executed during his previous hospital admission (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasound in a patient with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma showing: (A) enlarged homogeneous liver (long axis 20 cm) and (B) splenomegaly (long axis 19 cm) with slightly heterogeneous structure. There is no peritoneal effusion.

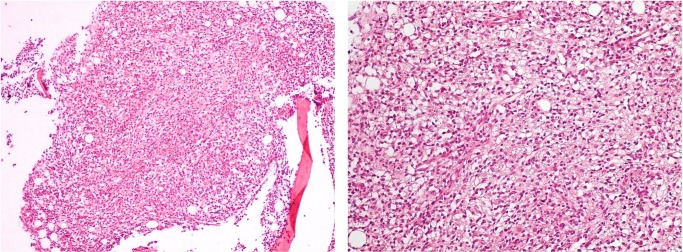

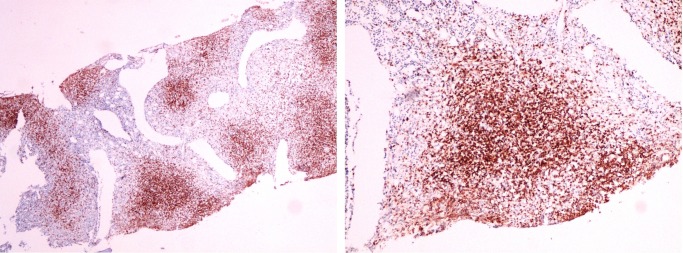

New CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing a homogeneously enlarged liver (long axis, 21 cm) and massive splenomegaly (20 cm), with hypodensities in the anterior and posterior aspects of the spleen, most likely representing lymphomatous involvement; there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy (figure 2). A second bone marrow sample was collected, which showed a hypercellular marrow with an extensive infiltration by small mature T-lymphocytes mostly in a nodular pattern (figure 3). Flow cytometry revealed tumour cells that expressed CD2, CD3 and CD7 positivity, but lacked expression of CD4, CD5 and CD8 (figure 4). In addition, malignant cells expressed the natural killer (NK) cell marker CD56, but were negative for B-cell-associated markers (CD19, CD20, CD22 and CD23).

Figure 2.

Abdominal CT demonstrates massive hepatosplenomegaly (long axis 21 and 20 cm, respectively) in a patient with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; there are no enlarged lymph nodes.

Figure 3.

Bone marrow biopsy revealing hypercellular marrow with an extensive infiltration by small mature T-lymphocytes (H&E staining at ×100 and ×200 magnification).

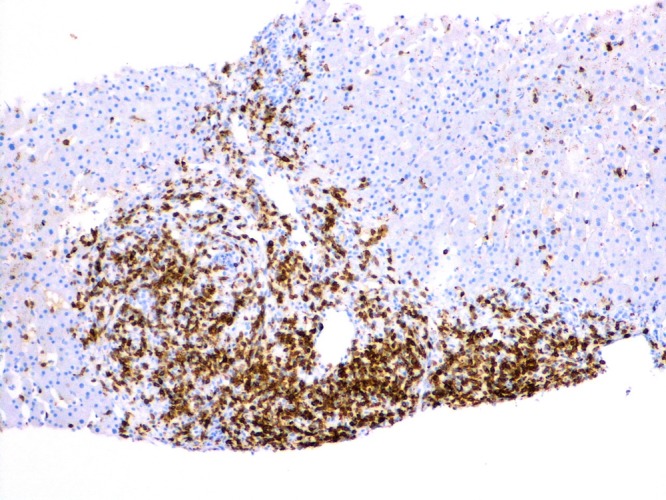

Figure 4.

CD3 immunohistochemical staining on the bone marrow biopsy specimen showing tumour cell infiltrates, mostly in a nodular pattern (magnification ×40 and ×100).

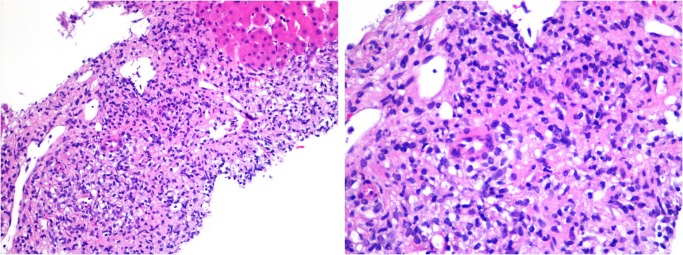

As the patient's symptoms continued to progress, a transjugular liver biopsy was performed, revealing portal and sinusoidal infiltration by small-to-medium sized lymphocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei, some of which showed atypical mitoses (figure 5). A few small non-caseating granulomas were seen within the hepatic lobules. There were no iron deposits and no haemophagocytosis present in the biopsy specimen. Immunohistochemical stains showed positive staining for CD3, CD7, CD56, TIA1 and Granzyme B (figure 6), similar to that seen within the bone marrow.

Figure 5.

Histology and immunohistochemistry of a transjugular liver biopsy showing portal and sinusoidal infiltration by atypical small-to-medium sized lymphocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei and low mitotic activity, similar to that seen within the sinusoids of the bone marrow (H&E staining at ×200 and ×400 magnification).

Figure 6.

CD3 immunohistochemical staining on a liver biopsy specimen at ×100 magnification.

Differential diagnosis

As a differential diagnosis, we considered infectious diseases, haematological malignancies including leukaemia, lymphoma and mieloproliferative disorders, and infiltrative diseases such as amyloidosis and sarcoidosis.

Treatment

As soon as the diagnosis was established, the patient was initiated on chemotherapy with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxy doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) in association with methotrexate, with a transitory response. Autologous stem cell transplant (SCT) was considered.

Outcome and follow-up

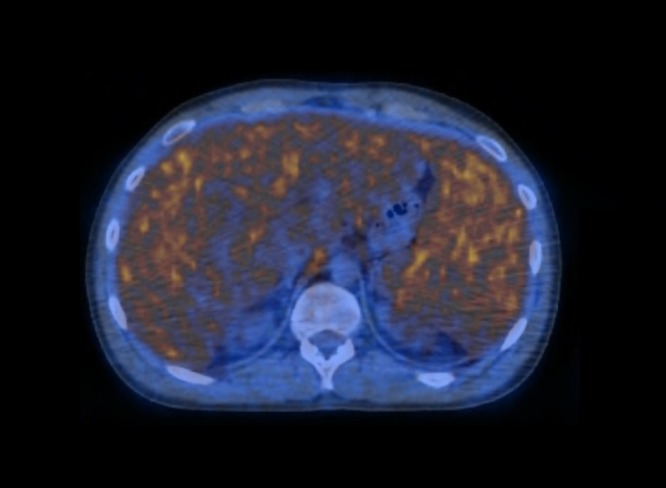

Positron emission tomography scan executed after the fourth cycle of chemotherapy showed lymphoproliferative disease with high metabolic activity in the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and supradiaphragmatic and infradiaphragmatic lymph nodes (figure 7). Despite the aggressive treatment with four cycles of multiagent chemotherapy, remission was not achieved and the patient died 4 months after the diagnosis.

Figure 7.

A positron emission tomography scan of the patient with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma demonstrates high metabolic activity in the liver, spleen and bone marrow.

Discussion

HSTCL is a rare subset of the peripheral T-cell lymphomas, accounting for less than 1% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas and about 3% of all T-cell lymphomas/leukaemias.1 2 The exact incidence is unknown and fewer than 100 patients have been reported in the literature.3 It was first described as a distinct clinicopathological entity in the 1990 REAL (Revised European American Lymphoma) Classification and it is characterised by extranodal infiltration and proliferation of malignant T cells within the sinusoids of the liver, sinuses and red pulp of the spleen, and the sinuses of the bone marrow.1 4 5 The median age at diagnosis is approximately 35 years (range 15–65 years), and there appears to be a male predominance, with a male to female ratio of about 9:1.3–7

Although the pathogenesis of HSTCL is poorly understood, it has been postulated that chronic antigen stimulation in the setting of immune deficiency or dysregulation might be important.8 Ten per cent to 20% of patients have a history of chronic immune suppression, such as that associated with treatment for a lymphoproliferative disorder, prior solid organ transplantation or inflammatory bowel disease.9 10 Regarding the latter, there has been an association between the development of HSTCL with the use of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, thiopurine, and the anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies infliximab and adalimumab in young patients with Crohn's disease.11–13 While the possibility of an infectious connection has been explored, and a few HSTCLs, including in our patient, were positive for EBV, there is no proven association between EBV infection and HSTCL.14–16

Patients with HSTCL typically present with hepatosplenomegaly, minimal or no peripheral lymphadenopathy, and with constitutional or ‘B’ symptoms, including fever, weight loss and night sweats. Thrombocytopaenia is commonly seen, although this may be part of a broader pancytopaenia. The cause of the cytopaenias is multifactorial: marrow infiltration, splenic sequestration, haemolytic anaemia, immune-mediated thrombocytopaenia or haemophagocytic syndrome, either alone or in combination.7 8 Although peripheral lymphocytosis is uncommon, a small population of circulating neoplastic lymphocytes may be seen at initial presentation in approximately 50% of patients with HTCSL. With disease progression, the number and size of the malignant T-cells may increase and they may undergo ‘blastic evolution’, resembling acute leukaemia at the terminal stage.7 Since the blood smear changes in patients with HSTCL are unremarkable, diagnosis is generally based on biopsy specimens of bone marrow, liver and/or spleen. Histologically, small-to-intermediate sized T lymphocytes infiltrate the sinusoids of the liver and the splenic red pulp, while the bone marrow is involved in approximately two-thirds of patients at presentation. Flow cytometry and immunophenotyping of biopsy specimens are essential for diagnosis. The tumour cells usually express CD2, CD3, CD7 and CD 26, but are mostly CD4, CD5 and CD8 negative, and express a clonally restricted γ–δ (or less commonly α–β) T-cell receptor.17–20 NK cell-associated markers CD16, CD56 and CD57 are frequently expressed.14 An isochromosome of the long arm of chromosome 7 (i(7)(q10)) is a recurrent genetic abnormality described in HSTCL, either in isolation or in association with trisomy 8 and a loss of a sex chromosome.21–24

The diagnosis of HSTCL may be overlooked initially because of its rarity, and must be distinguished from other lymphoid neoplasms (NK-cell leukaemia, T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukaemia, T-lymphoblastic leukaemia type II, splenic marginal zone lymphoma, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and primary cutaneous γ-δ T-cell lymphoma), myelodysplasic syndrome, and infiltrative and infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, leishmaniasis and mononucleosis.7 25–29 In addition to extensive immunophenotypic analysis, cytogenetic and molecular studies are occasionally needed for establishing a definitive diagnosis.30

HSTCL has a dismal clinical course with poor prognosis, and a reported median overall survival of 6–11 months.14 31 32 To date, the most common therapeutic strategies have been CHOP and HyperCVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone), alternating with high-dose methotrexate and cytorabine, followed by autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.3 7 14 While some patients initially respond to chemotherapy, relapse is seen in most cases, and the majority of patients die from disease progression within 2 years of diagnosis.7 Recent reports have suggested improved outcome and survival with intensive induction chemotherapy followed by early high-dose therapy and haematopoietic SCT; however, additional data to support these aggressive strategies are needed.33–36

Our case confirmed that HSTCL should be considered in young male immunocompetent patients presenting with hepatosplenomegaly, systemic symptoms and abnormal blood findings, but no substantial lymphadenopathy. Diagnostic challenges may occasionally arise, especially in the setting of inconclusive examinations, requiring repeated radiological and invasive procedures (biopsies) for establishing a definitive diagnosis. A prompt recognition of this rare T-cell neoplasm is important, so that patients can be managed aggressively in order to induce remission followed eventually by early SCT. Additionally, portrayal of more cases with new clinical and biological features is required with the aim of developing novel therapeutic strategies in the near future.

Learning points.

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) is a very rare and aggressive form of peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The diagnosis is usually established from the combination of clinical findings, histological features and immunophenotypic analysis from biopsy specimens of bone marrow, liver and/or spleen.

The clinical course is aggressive with an unsatisfactory response to currently available therapies, and a median overall survival of 1 year.

HSTCL should be considered in young men presenting with hepatosplenomegaly, systemic symptoms and abnormal peripheral blood findings, with no substantial lymphadenopathy.

A prompt recognition of this rare neoplasm is important, so that patients can be managed aggressively in order to induce remission followed eventually by early stem cell transplantation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of the Pathologist, Dr Carlos Abrantes, who carefully selected and provided photographs to enrich this paper. They would also like to thank Dr Elsa Gaspar and Dr Diana Mota, who were involved in the patient's care and treatment. A special thanks to Dr David Donaire for his help with the radiology images presented here.

Footnotes

Contributors: MP was the assistant physician responsible for the patient's diagnosis and also for gathering data and writing the manuscript. MMG and JPNC were responsible for diagnosing the patient and editing the manuscript. JPdM was the head of the medical team and was responsible for the revision of the manuscript and for giving the final approval.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 1994;84:1361–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL et al. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical application. Blood 2011;117:5019–32. 10.1182/blood-2011-01-293050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falchook GS, Vega F, Dang NH et al. Hepatosplenic gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma: clinicopathological features and treatment. Ann Oncol 2009;20:1080–5. 10.1093/annonc/mdn751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farcet JP, Gaulard P, Marolleau JP et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: sinusal/sinusoidal localization of malignant cells expressing the T-cell receptor gamma delta. Blood 1990;75:2213–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J et al. The World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting, Airlie House, Virginia, November, 1997. Ann Oncol 1999;10:1419–32. 10.1023/A:1008375931236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D, International T-Cell Lymphoma Project. International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4124–30. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y, Wang E. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic review with an emphasis on diagnostic differentiation from other T-cell/natural killer-cell neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015;139:1173–80. 10.5858/arpa.2014-0079-RS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashmore P, Patel M, Vaughan J et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a case series. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 2015;8:78–84. 10.1016/j.hemonc.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross CW, Schnitzer B, Sheldon S et al. Gamma/delta T-cell posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder primarily in the spleen. Am J Clin Pathol 1994;102:310–15. 10.1093/ajcp/102.3.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.François A, Lesesve JF, Stamatoullas A et al. Hepatosplenic gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma: a report of two cases in immunocompromised patients, associated with isochromosome 7q. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:781–90. 10.1097/00000478-199707000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackey AC, Green L, Liang LC et al. Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma associated with infliximab use in young patients treated for inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;44:265–7. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31802f6424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotlyar DS, Osterman MT, Diamond RH et al. A systematic review of factors that contribute to hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:36–41. 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beigel F, Jürgens M, Tillack C et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in a patient with Crohn's disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;6:433–6. 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weidmann E. Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma. A review on 45 cases since the first report describing the disease as a distinct lymphoma entity in 1990. Leukemia 2000;14:991–7. 10.1038/sj.leu.2401784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parakkal D, Sifuentes H, Semer R et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients receiving TNF-α inhibitor therapy: expanding the groups at risk. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;23:1150–6. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834bb90a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothenberg ME, Weber WE, Longtine JA et al. Cytotoxic gamma delta I lymphocytes associated with an Epstein-Barr virus-induced posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1996;80:266–72. 10.1006/clin.1996.0122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alsohaibani FI, Abdulla MA, Fagih MM. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2011;27:39–42. 10.1007/s12288-010-0051-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizvi MA, Evens AM, Tallman MS et al. T-cell non-Hodgikin lymphoma: review article. Blood 2006;107:1255–64. 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suarez F, Wlodarska I, Rigal-Huguet F et al. Hepatosplenic alphabeta T-cell lymphoma: an unusual case with clinical, histologic, and cytogenetic features of gammadelta hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1027–32. 10.1097/00000478-200007000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macon WR, Levy NB, Kurtin PJ et al. Hepatosplenic alphabeta T-cell lymphomas: a report of 14 cases and comparison with hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:285–96. 10.1097/00000478-200103000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wlodarska I, Martin-Garcia N, Achten R et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization study of chromosome 7 aberrations in hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: isochromosome 7q as a common abnormality accumulating in forms with features of cytologic progression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2002;33:243–51. 10.1002/gcc.10021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonveaux P, Daniel MT, Martel V et al. Isochromosome 7q and trisomy 8 are consistent primary, non-random chromosomal abnormalities associated with hepatosplenic T gamma/delta lymphoma. Leukemia 1996;10:1453–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conventry S, Punnett HH, Tomczak EZ et al. Consistency of isochromosome 7q and trisomy 8 in hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphoma: detection by fluorescence in situ hybridization of a splenic touch preparation from a pediatric patient. Pediatr Dev Pathol 1999;2:478–83. 10.1007/s100249900152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shetty S, Mansoor A, Roland B. Ring chromosome 7 with amplification of 7q sequences in a pediatric case of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2006;167:161–3. 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nosari A, Oreste PL, Biondi A et al. Hepatosplenic γδ T-cell lymphoma: a rare entity mimicking the hemophagocytic syndrome. Am J Hematol 1999;60:61–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooke CB, Krenacs L, Stetler-Stevenson M et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity of cytotoxic gamma delta T-cell origin. Blood 1996;88:4265–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arps DP, Smith LB. Classic versus type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: diagnostic considerations. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013;137:1227–31. 10.5858/arpa.2013-0242-CR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YH, Peterson L. Differential diagnosis of CD4-/CD8- γδ T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;137:496–7. 10.1309/AJCPCOPRE1HGD0FC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamini O, Jain P, Konoplev SN et al. CD4(-)/CD8(-) variant of T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia or hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic dilemma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2013;13:610–13. 10.1016/j.clml.2013.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad E, Kingma DW, Jaffe ES et al. Flow cytometric immuno-phenotypic profiles of mature gamma delta T-cell malignancies involving peripheral blood and bone marrow. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2005;67:6–12. 10.1002/cyto.b.20063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belhadj K, Reyes F, Farcet JP et al. Hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphoma is a rare clinicopathologic entity with poor outcome: report on a series of 21 patients. Blood 2003;102:4261–9. 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lladó AC, Tomé AL, Henrique M et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a rare cause of hepatosplenomegaly. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:pii bcr2013009423 10.1136/bcr-2013-009423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voss MH, Lunning MA, Maragulia JC et al. Intensive induction chemotherapy followed by early high-dose therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation results in improved outcome for patients with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a single institution experience. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2013;13:8–14. 10.1016/j.clml.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chanan-Khan A, Islam T, Alam A et al. Long-term survival with allogeneic stem cell transplant and donor lymphocyte infusion following salvage therapy with anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody (Campath) in a patient with alpha/beta hepatosplenic T-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2004;45:1673–5. 10.1080/10428190310001609924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konuma T, Ooi J, Takahashi S et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2007;48:630–2. 10.1080/10428190601126941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ooi J, Iseki T, Adachi D et al. Successful allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for hepatosplenic gammadelta T cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2001;86:E25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]