Summary

Background

The angiotensin (Ang) converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas receptor pathway is an important component of the renin–angiotensin system and has been suggested to exert beneficial effects in ischemic stroke.

Aims

This study explored whether the ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas pathway has a protective effect on cerebral ischemic injury and whether this effect is affected by age.

Methods

We used three‐month and eight‐month transgenic mice with neural over‐expression of ACE2 (SA) and their age‐matched nontransgenic (NT) controls. Neurological deficits and ischemic stroke volume were determined following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). In oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) experiments on brain slices, the effects of the Mas receptor agonist (Ang1‐7) or antagonist (A779) on tissue swelling, Nox2/Nox4 expression reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and cell death were measured.

Results

(1) Middle cerebral artery occlusion ‐induced ischemic injury and neurological deficit were reduced in SA mice, especially in eight‐month animals; (2) OGD‐induced tissue swelling and cell death were decreased in SA mice with a greater reduction seen in eight‐month mice; (3) Ang‐(1–7) and A779 had opposite effects on OGD‐induced responses, which correlated with changes in Nox2/Nox4 expression and ROS production.

Conclusions

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas axis protects brain from ischemic injury via the Nox/ROS signaling pathway, with a greater effect in older animals.

Keywords: Aging, Angiotensin, Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2, Ischemic stroke, NADPH oxidase

Introduction

Stroke is the fourth leading cause of death, and the number one cause of disability in the world. Its prevention and treatment remains one of the most challenging public health problems Clinical and experimental studies suggest that the angiotensin (Ang) converting enzyme (ACE)/Ang II/AT1 receptor (AT1R) pathway of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) participates in the pathophysiology of ischemic stroke 1. In addition, aging is well known as one of the risk factors for stroke 2, 3. There is emerging evidence to suggest that the Ang II/AT1R pathway plays an important role in age‐related vascular dysfunction 4. The ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas axis, a component of the RAS first described 5, 6, 7 is widely distributed in the brain including cells of the cerebral vasculature, neurons, and glia and exerts its protective effect by counteracting the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis 8. Accumulating evidence indicates that both of these RAS signaling pathways participate in the regulation of cerebrovascular blood flow, blood pressure, and neuroendocrine function 9, 10. Furthermore, a recent report showed that intracerebroventricular injection of Ang‐(1–7) had beneficial effects on ischemic stroke 11. Although the role of the ACE/Ang II/AT1 axis has been well detailed, the complex role of brain ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas pathway in ischemic stroke remains poorly understood.

Transgenic and knockout mouse models have been developed for exploring the role of the RAS in controlling cerebrovascular function 5, 8, 12, 13. It has also been shown by others 14 and us 15 that ischemia‐induced brain damage is exaggerated in human renin and angiotensinogen double‐transgenic mice. Using an ACE2 knockout mouse model, a recent study reported that ACE2 deficiency impairs endothelium‐dependent dilatory function in cerebral arteries and augments age‐related endothelial dysfunction via oxidative stress 16.

Oxidative stress is a condition of increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The NOX family of NADPH oxidases has been shown to induce ROS production in cells of the brain including microglia, neurons, astrocytes, and the various cellular components of the neurovascular system 17. Recent evidence demonstrates that NOX2 and Nox4 appear to be major sources of pathological oxidative stress in the brain such as stroke 14. It has been well established that AngII stimulates NADPH oxidases‐mediated ROS production in the brain 18. We hypothesized that by transforming Ang II into Ang‐(1‐7). ACE2 might reduce AngII‐mediated oxidative stress in the brain and protect brain from ischemic injury. However, the role and mechanism of brain ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas pathway during ischemic injury also deserves more in‐depth investigation.

In this study, three‐month and eight‐month‐old transgenic mice were used. We examined the role of the ACE2/Ang‐(1–7) pathway on brain ischemic injury and its relation with age in these transgenic animals. First, we determined the pathological and behavioral severity of focal ischemic damage induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in mice with neuronal over‐expression of ACE2 (SA) and their age‐match controls (NT). Next, to exclude the effects of hemodynamic factors, we conducted studies on brain slices exposed to oxygen‐glucose deprivation (OGD) coupled with pharmacological activation or blockade of Mas receptors. The underlying mechanism was explored by analyzing Nox expression and ROS production.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals were obtained from Fischer Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Propidium iodide (PI) and dihydroethedium (DHE) were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). The heptapeptide Ang‐(1–7) and the Mas receptor inhibitor A779 were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The Complete Mini protease inhibitors and lysis buffer for protein extraction were ordered from Roche Diagnostics Corporation (Indianapolis, IN, USA). The Bradford protein analysis kit and precast polyacrylamide gels were obtained from Bio‐Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). Primary antibodies for β‐actin (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and for Nox2 and Nox4 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and HRP‐conjugated donkey anti‐rabbit IgG antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) were purchased from commercially vendors.

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of Wright State University and conformed to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Transgenic mice with ACE2 over‐expression in neurons (SA) and their controls (NT) were bred in our laboratory using founders provided by Dr. Eric Lazartigues (Louisiana State University, New Orleans, LA, USA) 15. Animals were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle and provided access to food and water ad libitum. Three‐month and eight‐month‐old mice (male and female) were used for the study.

Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Surgery, Evaluation of Neurological Deficits and Infarct Volume

Permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) surgery was performed in mice anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane inhalation, as previously described 19. Evaluation of neurological deficits was carried out 24 h after MCAO surgery according to a previously described five‐level scoring method 15. The scores ranged from 0 to 4 with the following definitions: 0, no observable neurological deficits; 1, failure to extend right forepaw; 2, circling to the right; 3, falling to the right; and 4, cannot walk spontaneously. The extent of ischemic infarction was evaluated 48 h after MCAO by staining brain sections with 2% 2,3,5‐triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Sigma), followed by analysis with NIH Image J software. The area of infarction was measured in each section by subtracting the stained area on the lesioned ipsilateral hemisphere from the total area of the nonlesioned contralateral hemisphere. The volume of infarction was calculated by summing the area of infarct [mm2] × thickness [1 mm] over all sections 15. The person performing the neurological deficit evaluation and measurement of infarct volume was unaware of animal group information.

Oxygen and Glucose Deprivation on Brain Slices

OGD experiments on brain slices were performed as previously described 15. Brains were rapidly dissected from the cranium, mounted on a block of agar with cyanoacrylate cement, and sectioned in a coronal plane into 400 μm‐thick slices using a Vibratome Section System (Series 1000). Brain slices were incubated in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) bubbled with 95% O2 plus 5% CO2 at room temperature for 1–2 h. After incubation, slices were transferred to an interface‐type recording stage (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) and initially perfused for baseline recording with aCSF at 35°C for 30 min under the same atmosphere. Then, the slices were exposed to control or OGD treatment for 30 min. In experiments that evaluated the role of the Ang‐(1–7)/Mas pathway, the Mas agonist Ang‐(1–7) (10 μm) or the Mas antagonist A779 (10 μm) was added into the perfusing solution at the start of OGD exposure 20, 21.

Assessment of Brain Swelling

As we previously described 15, tissue swelling was determined indirectly by measuring the intrinsic optical signal (IOS). Regions of interest were defined in stratum radiatum of the hippocampal CA1 area and in an equivalent area in the center of the adjacent cerebral cortex. The average light intensities in these areas were calculated and normalized to the average intensity measured in the same region immediately prior to the start of OGD exposure. IOS is expressed as the percent change in light intensity relative to this initial measurement.

Evaluation of Cell Death

Cell death in brain slices was determined using propidium iodide (PI) staining 15. Following the 30‐min treatment with control or OGD, slices were incubated in aCSF with 20 μg/mL PI at room temperature for 15 min and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. PI‐positive cells were visualized using a laser confocal microscope (TCS SP2; Leica, Exton, PA, USA).

Western Blot Analysis

Following the 30‐min treatment with control or OGD, slices were quickly removed from the perfusion chamber and homogenized on ice in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and EDTA. Total protein content of the solution was determined using the Bradford protein assay. Equal amounts (50 μg) of protein were re‐loaded into lanes of a 12% precast gel, separated by electrophoresis and then electrotransferred onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% nonfat dry milk and were probed with primary monoclonal mouse anti‐mouse β‐actin (1:4000), polyclonal rabbit anti‐mouse Nox2 (1:1000), or polyclonal rabbit anti‐mouse Nox4 (1:500) overnight at 4°C. Membranes then were washed and incubated with HRP‐conjugated donkey anti‐rabbit IgG (1:40,000). Blots were probed using enhanced chemiluminescence and visualized using a Fuji film image analyzer (Molecular Dynamics Image Quant, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Nox2, and Nox4 bands were visualized at an apparent molecular weight of 65 kDa and 67 kDa, respectively.

Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species Production

Dihydroethidium (DHE) was used to evaluate the generation of ROS products in slices exposed to control conditions or OGD. After the initial 30 min perfusion with control aCSF at 35°C, slices were perfused with 10 μm DHE for 30 min in control conditions or during OGD. During DHE treatment, the light source illuminating the slice and other room lights were turned off. After this treatment, slices were fixed for at least 1 h with 4% paraformaldehyde in staining buffer consisting of 137 mm NaCl plus 10 mm Na2HPO4 (pH 7.4). They then were washed for 20 min with staining buffer and mounted on glass slides under coverslips using Fluoro‐Gel aqueous mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Services, Hatfield, PA, USA). Photographs of the pyramidal cell layer in the middle of the CA1 region and cerebral cortex immediately superior to this area were captured under epifluorescence illumination (Leica, HBO 100). Three regions of interest were defined at the level of CA1 and cortex in each coronal section (n = 7/group). The intensity of red fluorescence was semiquantitatively analyzed using NIH ImageJ software, and the average intensity in these areas was calculated. The values measured in slices exposed to OGD then were normalized to the average intensity measured in the same region in control slices and the data for slices exposed to OGD expressed as the percent difference in red fluorescence intensity relative to these control measurement.

Data Analysis

Continuous data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed using one‐ or two‐way anova, as appropriate. For comparison between experimental groups, Student's paired or unpaired t‐test was used. Changes in neurological deficit scores were expressed as median (range) and analyzed using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U‐test. For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Neuronal Over‐expression of ACE2 Reduces MCAO‐induced Cerebral Injury with a Greater Effect in Eight‐month‐Old Mice

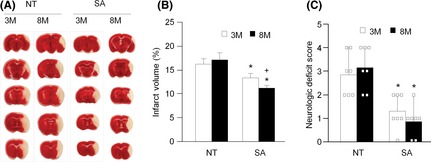

Using MCAO surgery to induce focal ischemic stroke in both NT and SA mice, we found that SA mice had lower neurological deficit scores measured at 24 h and less ischemic stroke volume 48 h after surgery (Figure 1A–C). The protective effect of ACE2 on ischemic stroke volume was greater in eight‐month‐old mice (Figure 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Neuronal over‐expression of ACE2 reduces MCAO‐induced cerebral injury in mice with enhanced efficacy in eight‐month mice. (A): representative TTC staining images of brain sections obtained 48 h after MCAO from NT and SA mice. (B): summarized data of infarct volumes. (C): summarized data of neurological deficit scores. SA: mice with neuronal over‐expression of ACE2; NT: wild‐type control mice; MCAO: middle cerebral artery occlusion; TTC: 2, 3, 5‐triphenyltetrazolium chloride; 3M: three‐month mice; 8M: eight‐month mice. *P < 0.05, NT vs. SA, + P < 0.05, vs. 3M, n = 7/group.

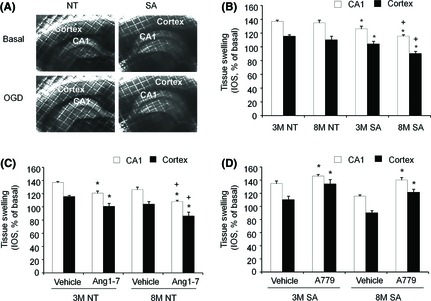

Neuronal Over‐expression of ACE2 Reduces OGD‐induced Brain Tissue Swelling with a Greater Effect in Eight‐month‐Old Mice

To determine blood flow‐ and pressure‐independent effects of ACE2 on cerebral ischemic injury, in vitro OGD experiments on brain slices were conducted. Figure 2A illustrates IOS in cerebral cortex and hippocampal areas as an index of OGD‐induced tissue swelling 15. We found that the IOS of brain slices from SA mice was significantly lower in both three‐month‐old and eight‐month‐old mice (Figure 2B). In addition, for slices from SA mice, but not NT mice, the IOS values in CA1 and cortex areas of were less at eight‐months of age compared with those measured in three‐month‐old mice (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Neural over‐expression of ACE2 or activation of Ang1‐7/Mas receptor pathway protects brain from OGD‐induced tissue swelling with enhanced efficacy in eight‐month mice. (A): Representative figures demonstrate the IOS in alive brain tissue at basal and after OGD. OGD induced tissue swelling was indexed by the increase of IOS in CA1 and cortex. Increase of IOS intensity is indicated by color from black to white. (B): Summarized data of neural over‐expression of ACE2 effect on OGD‐induced brain tissue swelling. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 7/group, *P < 0.05, vs. NT, + P < 0.05, vs. 3M. (C): Summarized data of Ang1–7 (10 μm) effect on OGD‐induced brain tissue swelling. (D): Summarized data of A779 (10 μm) effect on OGD‐induced brain tissue swelling. IOS: intrinsic optical signal; OGD: oxygen and glucose deprivation; 3M: three‐month mice; 8M: eight‐month mice. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 7/group, *P < 0.05, vs. Vehicle, + P < 0.05, vs. 3M.

Activation of the Ang‐(1–7)/Mas Receptor Pathway Protects Brain from OGD‐induced Swelling with a Greater Effect in Eight‐month‐Old Mice

To address the role of the Ang‐(1–7)/Mas pathway for ischemia‐induced brain swelling, either Ang‐(1–7) (10 μm) or A779 (10 μm) was added to the aCSF perfusing NT and SA slices during OGD exposure. While addition of Ang‐(1–7) reduced the magnitude of IOS in slices from NT mice at both three‐months and eight‐months of age, the change due to Ang‐(1–7) treatment was greater in the eight‐month‐old group (Figure 2C). For SA mice, blockade of Mas receptors by A779 increased the magnitude of IOS response in both three‐month‐old and eight‐month‐old mice (Figure 2D).

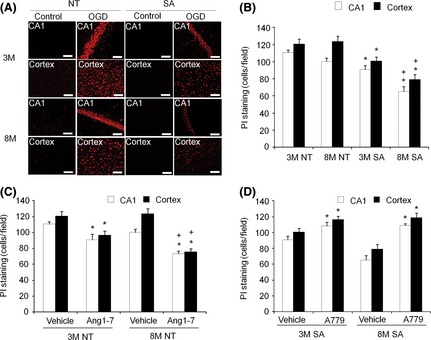

The ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas Pathway Reduces OGD‐induced Cell Death in the Brains of SA mice with a Greater Effect in Eight‐month‐Old Animals

OGD‐induced cell death both in cerebral cortex and the CA1 region of the hippocampus. OGD‐induced cell death was much reduced in SA mice compared with that observed in NT mice. We found that the difference between SA mice and NT mice was more pronounced in eight‐month‐old mice than that was observed in three‐month‐old mice (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

Neural over‐expression of ACE2 or activation of Ang1‐7/Mas receptor pathway protects brain from OGD‐induced cell death with enhanced efficacy in eight‐month mice. (A): Representative figures demonstrate the PI staining in control and OGD brain tissues. OGD‐induced cell death was indexed by the PI ‐positive cells in CA1 and cortex. The scale bars indicate 75 μm. (B): Summarized data of neural over‐expression of ACE2 effect on OGD‐induced brain cell death. Data are mean ±SEM, n = 7/group, *P < 0.05 vs. NT, + P < 0.05 vs. 3M. (C): Summarized data of Ang1–7 (10 μm) effect on OGD‐induced cell death. (D): Summarized data of A779 (10 μm) effect on OGD‐induced cell death. PI: propidium iodide; 3M: three‐month mice; 8M: eight‐month mice, n = 7/group, *P < 0.05 vs. Vehicle, + P < 0.05 vs. 3M.

Ang‐(1–7) treatment during OGD significantly decreased the number of PI‐positive cells in both brain regions of three‐month‐old and eight‐month‐old NT animals. As with ACE2 over‐expression, the effect of Ang‐(1–7) was more apparent in eight‐month‐old, as compared with three‐month‐old mice (Figure 3C). In addition, blockade of Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas signaling by A779 in SA mice increased the numbers of PI‐positive cells in both brain regions of three‐month‐old and eight‐month‐old animals (Figure 3D).

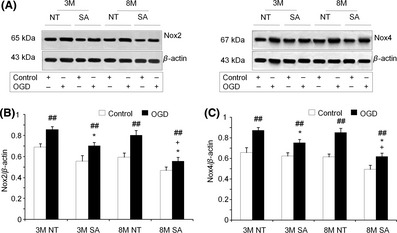

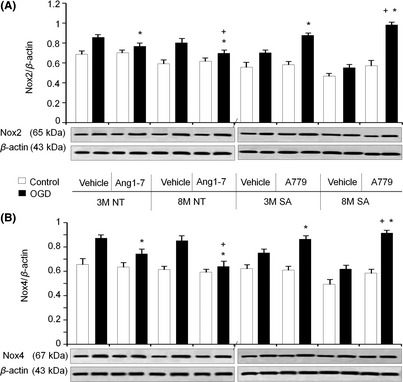

The ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas Pathway Inhibits the Up‐regulation of Brain Nox2 and Nox4 expression following OGD with Greater Effects seen in Eight‐month‐Old Mice

Neuronal over‐expression of ACE2 in SA mice did not change the basal expression of Nox2 and Nox4. In addition, for both animal genotypes, OGD caused an up‐regulation of Nox2 and Nox4 expression in brain tissue of both three‐month‐old and eight‐month‐old mice. However, levels of Nox2 and Nox4 expression in slices from SA mice following OGD exposure were significantly lower for both three‐month‐old and eight‐month‐old animals. This difference in Nox expression between NT and SA animals was greater in eight‐month‐old mice (Figure 4A–C).

Figure 4.

Neural over‐expression of ACE2 decreases OGD‐induced Nox2 and Nox4 up‐regulation with enhanced efficacy in eight‐month mice. (A): Representative figures demonstrate the Nox2 and Nox4 expression in brain tissue in the control and after OGD. OGD‐induced Nox2 and Nox4 expression was indexed by Western Blots. (B, C): Summarized data. 3M: three‐month mice; 8M: eight‐month mice. Mean ± SEM, n = 6/group, *P < 0.05, vs. NT, + P < 0.05, vs. 3M, ## P < 0.01, vs. Control.

In separate experiments, Ang‐(1–7) was added to brain slices from NT animals during OGD exposure. With Ang‐(1–7) treatment during OGD, the increase in expression of Nox2 and Nox4 was smaller at both three‐months and eight‐months of age. A greater effect of Ang‐(1–7) was seen in eight‐month‐old NT mice compared with three‐month‐old animals (Figure 5). In contrast, when the Mas receptor antagonist A779 was applied to brain slices from SA animals during OGD expose, the increase in both Nox2 and Nox4 expression was greater than that observed in the absence of added drug. This effect of A779 was significantly greater in eight‐month‐old SA mice compared with three‐month‐old animals (Figure 5). These data suggest that the control of Ang‐(1–7)/Mas pathway in OGD‐induced Nox over‐expression could be more important in the middle‐aged animals than that in young animals.

Figure 5.

Effect of Ang1‐7/Mas receptor pathway on OGD‐induced brain Nox2 and Nox4 expression. (A): Summarize date of Nox2 expression. (B): Summarize date of Nox4 expression. 3M: three‐month mice; 8M: eight‐month mice. Mean ± SEM, n = 6/group, *P < 0.05, vs. Vehicle, + P < 0.05, vs. 3M.

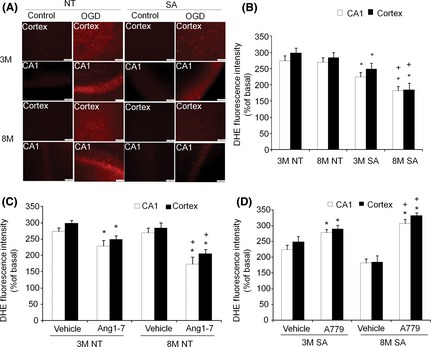

The ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas Pathway Decreases OGD‐induced ROS Production with a Greater Effect in Eight‐month‐Old Mice

To further explore whether the effect of the ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas axis on Nox expression has a functional implication, OGD‐induced ROS production was measured by DHE staining. The DHE fluorescence intensity was greater following OGD treatment for both animal genotypes. This increase was smaller in slices from SA animals than in slices from NT animals. In addition, the difference in DHE fluorescence intensity between SA and NT animals was greater for eight‐month‐old animals compared with three‐month‐old animals (Figure 6A–C). For SA mice, A779 increased the magnitude of ROS production in both brain regions of three‐month‐old and eight‐month‐old animals. This effect of A779 in slices from SA mice was greater in eight‐month‐old mice (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Neuronal over‐expression of ACE2 or activation of Ang1‐7/Mas receptor pathway reduces OGD‐induced ROS production in brain slices with enhanced efficacy in eight‐month mice. (A): Representative figures of DHE staining in the brain slices of 3M and 8M NT and SA mice. The scale bars indicate 100 μm. (B): Summarized data of neural over‐expression of ACE2 effect on OGD‐induced ROS production. n = 7/group, *P < 0.05 vs. NT, + P < 0.05 vs. 3M. (C): Summarized data of Ang1‐7 (10 μm) effect on OGD‐induced ROS production. (D): Summarized data of A779 (10 μm) effect on OGD‐induced ROS production. n = 7/group, *P < 0.05 vs. Vehicle, + P < 0.05 vs. 3M. ROS: reactive oxygen species; 3M: three‐month mice; 8M: eight‐month mice.

Discussion

The ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas axis has been demonstrated to be a functional arm of the RAS that can counteract deleterious effects of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis 8, 22. Mas receptor activation has various physiological functions such as regulating blood pressure 23, attenuating the progress of atherosclerosis through inhibiting vascular smooth muscle‐cell proliferation and restoring endothelial function 8, 24. The protective role of the ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas axis in cardiovascular 25, 26 and cerebrovascular 11, 27 diseases has gained much attention in recent years. Activation of Ang‐(1–7)/Mas signaling attenuates the development of hypertension 28 and the pathologic progress of atherosclerosis 29. However, there is limited information on the role of brain ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas axis in ischemic stroke.

In this study, we found that neuronal over‐expression of ACE2 protects the brain from ischemic injury. This is evidenced by lower neurological deficit scores and smaller stroke volumes following MCAO‐induced stroke in SA mice. Our results are supported by recent studies showing that intracerebroventricular (icv) infusion of Ang‐(1–7) or an ACE2 activatorreduces ischemic injury in rats mediated by a reduction in cerebral blood flow 11, 27. Central administration of Ang‐(1–7) was shown to exert a neuroprotective effect on ischemic injury by inhibiting the NF‐kappaB inflammation pathway 27. To address blood pressure/flow‐independent effects of the brain ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas pathway on ischemic stroke, we measured OGD‐induced swelling and cell death in brain tissue by using methods we previously established 15. We found that brain tissue from SA mice displayed less swelling and cell death in response to OGD. We further observed that application of Ang‐(1–7) reduces OGD‐induced tissue swelling and cell death in NT mice. In contrast, blockade of Mas receptor in SA mice with A779 has opposite impacts. Thus, our data provide the first evidence that activation of ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas pathway can exert a direct neuroprotective action by alleviating ischemia‐induced cell swelling and cell death.

Aging is known as one of the risk factors for cerebrovascular diseases associated with cerebrovascular dysregulation 2, 3, 4, 30, 31. It is suggested that the Ang II/AT1R pathway contributes to dysfunction 4, However, the age‐dependent role and mechanism of the brain ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas pathway for stroke is unclear. Unexpectedly, our in vivo and in vitro data did not show significant differences in MCAO‐induced or OGD‐induced brain injury between three‐month and eight‐month NT mice. These results are different from previous reports showing acute functional outcomes are worse with aging 32, 33, 34. Those studies showed that advanced‐age (15–24 month) increases the inflammatory response 32 and oxidative damage 33 and exacerbates cerebromicrovascular injury and autoregulatory dysfunction 34. Although our eight‐month‐old NT animals had similar infarction volumes and neurological deficits as the three‐month‐old mice, the SA littermates at both ages showed reduced brain injury. We found that the protective effect of ACE2 in the SA mice is greater for the eight‐month‐old animals. This is evidenced by reduced infarct volume following MCAO surgery, and reduced brain slice swelling and cell death following OGD‐induced injury in eight‐month‐old SA mice compared with three‐month‐old SA mice. Our observations seem to be in accord with a recent report showing that ACE2 deficiency augments endothelial dysfunction during aging despite no significant change of ACE2 expression in aged brain 16. Using mice with ages comparable to ours, Miyamoto et al. 35 recently showed an age‐related decline in cyclic AMP response element‐binding protein mediated oligodendrogenesis. Our conclusions are also indirectly supported by recent reports showing that Ang II‐induced cerebromicrovascular injury and neuroinflammation are exacerbated by aging 33 and that the ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas pathway is critical for vasodepressor activity in aorta of aged rats 36. A study also showed that ACE2 deficiency is associated with the age‐dependent increase in BP and autonomic dysfunction 18.

To explore the possible mechanisms underlying the protective effect of the ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas pathway on ischemic stroke and the influence of aging, we measured NADPH oxidase expression and ROS production. Nox2 and Nox4 were significantly up‐regulated in response to OGD. However, these responses were reduced in SA mice. In addition, application of Ang‐(1–7) to NT animals or A779 to SA animals for activation or blockade respectively of the Mas receptor had reciprocal effects on Nox2 and Nox4 expression. These data suggest the ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas pathway is involved in the control of NADPH oxidase expression. Furthermore, the Nox expression data were well correlated with levels of ROS production. These findings are in agreement with previous studies showing ACE2 over‐expression prevents an Ang II‐induced increase in ROS production and NADPH oxidase expression in endothelia 24. In addition, ACE2 inhibition enhances Ang II‐stimulated ROS formation 37. We also found that neuronal ACE2 over‐expression reduced Nox2/Nox4 expression and ROS production to a greater extent in eight‐month‐old mice compared with that seen in three‐month‐old mice. The presence of this mechanism is also indirectly supported by previous reports showing that aging impairs eNOS‐dependent reactivity of cerebral arterioles via an increase in superoxide produced by activation of NADPH oxidase 2, 3.

In addition to Nox2 and Nox4, eNOS may play a role in the RAS‐induced oxidative stress seen during exposure to ODG. A previous study indicates that Ang‐(1–7) stimulates NO release and upregulates eNOS expression in ischemic tissues following stroke in rats 38. A recent report showed that the cerebroprotective properties of the ACE2/Ang‐(1–7)/Mas axis 11. Nox4‐derived hydrogen peroxide enhances eNOS activity and NO signaling 39. On the other hand, Nox4 may act as a potent stimulus for eNOS‐derived superoxide production which initiates eNOS dysfunction and decrease in NO levels in cells treated with Ang II 39. Nox1 and Nox2 have been linked to eNOS uncoupling in vascular pathology 40, 41. Whether the changes of Nox2 and Nox4 in this study might be related to NO and eNOS deserves further investigation.

In summary, this study provides the first evidence that activation of the ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas axis produces a direct protective effect during cerebral ischemic injury by alleviating cell swelling and cell death via decreased Nox expression and resulting lower ROS production. In addition, the protective effect of Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas activation on ischemic injury in the brain shows an age‐dependent trend. Therefore, the ACE2/Ang‐(1‐7)/Mas axis holds a great potential for the development of new targets in the management of ischemic stroke.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interests, financial, or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL‐098637 to YC and JEO; HL‐093178 to EL) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, #81271214).

References

- 1. Veerasingham SJ, Raizada MK. Brain renin‐angiotensin system dysfunction in hypertension: recent advances and perspectives. Br J Pharmacol 2003;139:191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayhan WG, Arrick DM, Sharpe GM, Sun H. Age‐related alterations in reactivity of cerebral arterioles: role of oxidative stress. Microcirculation 2008;15:225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park L, Anrather J, Girouard H, Zhou P, Iadecola C. Nox2‐derived reactive oxygen species mediate neurovascular dysregulation in the aging mouse brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007;27:1908–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Modrick ML, Didion SP, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Role of oxidative stress and AT1 receptors in cerebral vascular dysfunction with aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009;296:H1914–H1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doobay MF, Talman LS, Obr TD, Tian X, Davisson RL, Lazartigues E. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with overexpression of the brain renin‐angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007;292:R373–R381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gallagher PE, Chappell MC, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Distinct roles for ANG II and ANG‐(1‐7) in the regulation of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 in rat astrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006;290:C420–C426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van GH. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 2004;203:631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiang T, Gao L, Lu J, Zhang YD. ACE2‐Ang‐(1‐7)‐Mas axis in brain: a potential target for prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke. Curr Neuropharmacol 2013;11:209–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu P, Sriramula S, Lazartigues E. ACE2/ANG‐(1‐7)/Mas pathway in the brain: the axis of good. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2011;300:R804–R817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ishikawa M, Sekizuka E, Yamaguchi N, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor signaling contributes to platelet‐leukocyte‐endothelial cell interactions in the cerebral microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;292:H2306–H2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mecca AP, Regenhardt RW, O'Connor TE, et al. Cerebroprotection by angiotensin‐(1‐7) in endothelin‐1‐induced ischaemic stroke. Exp Physiol 2011;96:1084–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xia H, Feng Y, Obr TD, Hickman PJ, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor‐mediated reduction of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 activity in the brain impairs baroreflex function in hypertensive mice. Hypertension 2009;53:210–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feng Y, Xia H, Cai Y, et al. Brain‐selective overexpression of human angiotensin‐converting enzyme type 2 attenuates neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res 2010;106:373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inaba S, Iwai M, Tomono Y, et al. Exaggeration of focal cerebral ischemia in transgenic mice carrying human renin and human angiotensinogen genes. Stroke 2009;40:597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen S, Li G, Zhang W, et al. Ischemia‐induced brain damage is enhanced in human renin and angiotensinogen double‐transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009;297:R1526–R1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pena Silva RA, Chu Y, Miller JD, et al. Impact of ACE2 deficiency and oxidative stress on cerebrovascular function with aging. Stroke 2012;43:3358–3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sorce S, Krause KH, Jaquet V. Targeting NOX enzymes in the central nervous system: therapeutic opportunities. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012;69:2387–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xia H, Suda S, Bindom S, et al. ACE2‐mediated reduction of oxidative stress in the central nervous system is associated with improvement of autonomic function. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e22682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen J, Chen S, Chen Y, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cellular membrane microparticles in db/db diabetic mouse: possible implications in cerebral ischemic damage. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011;301:E62–E71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. D'Agostino DP, Putnam RW, Dean JB. Superoxide (*O2‐) production in CA1 neurons of rat hippocampal slices exposed to graded levels of oxygen. J Neurophysiol 2007;98:1030–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shichinohe H, Kuroda S, Yasuda H, et al. Neuroprotective effects of the free radical scavenger Edaravone (MCI‐186) in mice permanent focal brain ischemia. Brain Res 2004;1029:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Pinheiro SV, Sampaio WO, Touyz R, Campagnole‐Santos MJ. Angiotensin‐(1‐7) and its receptor as a potential targets for new cardiovascular drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2005;14:1019–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xia H, Sriramula S, Chhabra KH, Lazartigues E. Brain ACE2 shedding contributes to the development of neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res 2013;113:1087–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lovren F, Pan Y, Quan A, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme‐2 confers endothelial protection and attenuates atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008;295:H1377–H1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Calo LA, Schiavo S, Davis PA, et al. ACE2 and angiotensin 1‐7 are increased in a human model of cardiovascular hyporeactivity: pathophysiological implications. J Nephrol 2010;23:472–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Der SS, Huentelman MJ, Stewart J, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK. ACE2: a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2006;91:163–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jiang T, Gao L, Guo J, Lu J, Wang Y, Zhang Y. Suppressing inflammation by inhibiting the NF‐kappaB pathway contributes to the neuroprotective effect of angiotensin‐(1‐7) in rats with permanent cerebral ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol 2012;167:1520–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feng Y, Xia H, Santos RA, Speth R, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2: a new target for neurogenic hypertension. Exp Physiol 2010;95:601–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tesanovic S, Vinh A, Gaspari TA, Casley D, Widdop RE. Vasoprotective and atheroprotective effects of angiotensin (1‐7) in apolipoprotein E‐deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010;30:1606–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zuliani G, Cavalieri M, Galvani M, et al. Markers of endothelial dysfunction in older subjects with late onset Alzheimer's disease or vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 2008;272:164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Girouard H, Iadecola C. Neurovascular coupling in the normal brain and in hypertension, stroke, and Alzheimer disease. J Appl Physiol 2006;100:328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manwani B, Liu F, Scranton V, Hammond MD, Sansing LH, McCullough LD. Differential effects of aging and sex on stroke induced inflammation across the lifespan. Exp Neurol 2013;249:120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Toth P, Tucsek Z, Sosnowska D, et al. Age‐related autoregulatory dysfunction and cerebromicrovascular injury in mice with angiotensin II‐induced hypertension. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:1732–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosenzweig S, Carmichael ST. Age‐dependent exacerbation of white matter stroke outcomes: a role for oxidative damage and inflammatory mediators. Stroke 2013;44:2579–2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miyamoto N, Pham LD, Hayakawa K, et al. Age‐related decline in oligodendrogenesis retards white matter repair in mice. Stroke 2013;44:2573–2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bosnyak S, Widdop RE, Denton KM, Jones ES. Differential mechanisms of ang (1‐7)‐mediated vasodepressor effect in adult and aged candesartan‐treated rats. Int J Hypertens 2012;2012:192567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gwathmey TM, Pendergrass KD, Reid SD, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Angiotensin‐(1‐7)‐angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 attenuates reactive oxygen species formation to angiotensin II within the cell nucleus. Hypertension 2010;55:166–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang Y, Lu J, Shi J, et al. Central administration of angiotensin‐(1‐7) stimulates nitric oxide release and upregulates the endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression following focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Neuropeptides 2008;42:593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee DY, Wauquier F, Eid AA, et al. Nox4 NADPH oxidase mediates peroxynitrite‐dependent uncoupling of endothelial nitric‐oxide synthase and fibronectin expression in response to angiotensin II: role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 2013;288:28668–28686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dikalova AE, Gongora MC, Harrison DG, Lambeth JD, Dikalov S, Griendling KK. Upregulation of Nox1 in vascular smooth muscle leads to impaired endothelium‐dependent relaxation via eNOS uncoupling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010;299:H673–H679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu J, Xie Z, Reece R, Pimental D, Zou MH. Uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxidase synthase by hypochlorous acid: role of NAD(P)H oxidase‐derived superoxide and peroxynitrite. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006;26:2688–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]