Abstract

BACKGROUND

The current options for the treatment of acne vulgaris present many mechanisms of action. For several times, dermatologists try topical agents combinations, looking for better results.

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the efficacy, tolerability and safety of a topical, fixed-dose combination of adapalene 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris in the Brazilian population.

METHODS

This is a multicenter, open-label and interventionist study. Patients applied 1.0 g of the fixed-dose combination of adapalene 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel on the face, once daily at bedtime, during 12 weeks. Lesions were counted in all of the appointments, and the degree of acne severity, overall improvement, tolerability and safety were evaluated in each visit.

RESULTS

From 79 recruited patients, 73 concluded the study. There was significant, fast and progressive reduction of non-inflammatory, inflammatory and total number of lesions. At the end of the study, 75.3% of patients had a reduction of >50% in non-inflammatory lesions, 69.9% in inflammatory lesions and 78.1% in total number of lesions. Of the 73 patients, 71.2% had good to excellent response and 87.6% had satisfactory to good response. In the first week of treatment, erythema, burning, scaling and dryness of the skin were frequent complaints, but, from second week on, these signals and symptoms have reduced.

CONCLUSION

The fixed-dose combination of adapalene 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel is effective, safe, well tolerated and apparently improves patient compliance with the treatment.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris; Benzoyl peroxide; Combined modality therapy; Dermatology; Drug therapy, combination; Multicenter Study; Propionibacterium acnes; Skin diseases; Treatment outcome

INTRODUCTION

Acne vulgaris is a chronic skin disease that affects a lot of people, especially adolescents and young adults.1,2 It is known that about 85% of population between 12 and 24 years suffer from this disease. Lesions can persist into adulthood, affecting about 12% of women and 3% of men over 25 years. 2

The following factors are responsible for acne physiopathology: sebaceous hypersecretion, follicular hyperkeratinization, colonization of the hair follicle by the bacterium Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) and inflammatory response.3

The usual treatments for acne include topical antimicrobial agents, topical retinoids, oral and topical antibiotics, hormonal therapy and oral retinoids in the more severe cases. The isolated use of topical antibiotics should be limited because of the increased risk of bacterial resistance. Each of these classes of agents has a different mechanism of action, which leads the dermatologist to use combined therapies, seeking to achieve a better therapeutic result. 4

Adapalene (6-[3-(1-adamantyl)-4-methoxypheny l]-2-naphthoic acid), a retinoid derivative of naphthoic acid, is a highly effective comedolytic and anticomedogenic agent, which reverses the abnormal follicular "hyperkeratinization" process and microcomedones formation.5,6,7 It also antagonizes the action of P. acnes, reducing the expression of toll-like receptors 2 (TLR2), one of the responsible for the activation and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.8,9,10 Another action of the molecule is to modulate the immune response by altering the expression of CD1d and IL-10, causing the antimicrobial activity of the immune system itself to increase.10,11

Benzoyl peroxide (BPO; C14H10O4) is an agent with keratolytic properties and important antimicrobial and bactericidal action, which, unlike antibiotics, do not produce bacterial resistance.12,13 A meta-analysis performed with the pooled results of 3 randomized trials, comprising a total of 3855 patients, compared the efficacy of isolated adapalene, isolated BPO, vehicle and association of the 2 molecules in gel. It was observed the effect of BPO in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions, when used alone, with reduction of 46% in inflammatory lesions and 52% in non-inflammatory lesions after 12 weeks of treatment.14 This mechanism could be partly explained by the fact that BPO acts against P. acnes. This bacterium, by stimulating the release of IL-1 by follicular keratinocytes, would lead to hyperproliferation of keratinocytes, thus contributing to the appearance of comedones.12

In clinical practice, use of combined therapy has been shown to be more effective than monotherapies. 4 Currently the only commercially available combination of a retinoid and a BPO is adapalene 0.1% and BPO 2.5% gel. The efficacy of this combination proved to be higher than that of both molecules used separately in various studies in North America and Europe. 14,15-18 Tolerability and safety were comparable to those of adapalene and BPO monotherapy.19

The objective of this study is to observe the efficacy, safety and tolerability of this association in the Brazilian population.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design and duration:

This is a descriptive, open and interventionist study with participation of 6 Brazilians dermatological centers with experience in clinical research. Patients were instructed to apply over the entire face a thin layer (approximately 1 g of the product, which would be equivalent to the size of a pea) of the association of adapalene 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel, once daily at bedtime for 12 weeks. Patients were evaluated at weeks 0, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12

Study population:

The study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice. All participating patients signed the Informed Consent, prepared according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee corresponding to each center. Selected patients were male and female, aged between 12 and 35 years, affected by papular-pustular acne with the following characteristics:

- 20-50 inflammatory lesions (papules or pustules) and up to one nodule or a cyst on the face, except in the nose region;

- 30-100 comedones, open and closed, on the face, except in the nose region.

Patients in reproductive age used an appropriate contraceptive method during the study. Women who were planning pregnancy or breast-feeding were excluded from the study. Patients with photosensitizing diseases or requiring the use of topical and systemic medications that could interfere directly in the evaluating criteria of the results were not included. Patients using previous treatment for acne or other topical treatments on the face that could impact the results were instructed to discontinue the medication for at least 2 weeks before the start of the study. Patients using systemic retinoids were included only if their use preceded the start of the study in 6 months.

Treatment effectiveness measures:

Reduction of the number of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions on the face at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12.

Percentage of patients who achieved reduction of at least 50% in the number of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions in week 12.

Assessment of severity of acne according to the score recommended by this protocol at week 0, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12 (Chart 1).

Analysis of overall improvement by the investigator at week 12, as follows: excellent: >75%; good: 51-75%; satisfactory: 26-50%; low: ≤25%; no improvement: 0%.

Evaluation of improvement and satisfaction according to the patient at week 12.

Chart 1.

Acne severity scale

| Facial acne was evaluated following the scale below: | |

|---|---|

| 0 | No lesions, just presenting erythema or residual hyperpigmentation |

| 1 | Presence of a few comedones and a few small papules and pustules |

| 2 | Presence of some comedones, papules and pustules. No nodules present |

| 3 | Presence of many comedones, papules and pustules. One nodule may be present |

| 4 | Covered whth comedones, numerous papules and pustules. Presence of few nodules and cysts |

| 5 | Highly infammatory acne covering the face, with nodules and cysts present |

Safety and tolerability measure:

To assess tolerability, were observed at all visits: erythema, dryness, burning and scaling on the face according to the intensity, according to the table: 0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe. It was registered the presence or absence of adverse events during each visit.

Statistical analysis:

Exploratory data analysis was performed through summary measures (mean, standard deviation, minimum, median, mode, maximum, frequency and percentage) and graphics. Comparison between weeks of the severity of facial acne and number of lesion was performed using non-parametric Friedman test - Nemenyi procedure. Comparison between the presence or absence of adverse events (erythema, dryness, burning and scaling) was performed using the Cochran Q test with Marascuilo multiple comparison procedure.

Normality of the variables was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test k.

Analysis of overall improvement at week 12, percentage of patients with reduction of at least 50% in the number of lesion and other safety and tolerability assessments were performed using descriptive statistics.

Level of statistical significance was 5%. The software for statistical analysis was XLSTAT 2011.

RESULTS

-Population:

The study enrolled a total of 79 patients. Of these, 5 did not return until the last visit and one did not accept to keep a contraceptive method during the study and therefore they were excluded and disregarded from the analysis. The total final sample comprised 73 patients, of which 47 (64%) were men and 26 (36%) were women.

Patients' ages ranged from 12.2 to 35.3 years. Mean age was 18.3 years (SD ± 4.5).

Most patients (71%) were Caucasians and 29% were brown or black. Predominant phototype on the sample was type III (46.6%), followed by phototype II (21.9%), IV (19.2%), and V (9.6%). Only one patient was phototype I and one was phototype VI.

- Efficacy parameters:

• Number of lesions:

Number of inflammatory, noninflammatory and total lesions on the face (except in the nose region) was counted at all visits. Descriptive statistical measures used to analyze the evolution of the number of lesions according to the visits were median and percentage of change of median in relation to the baseline visit. Reduction of inflammatory and total lesions were significant as early as week 1 (Friedman; p <0.001). From the second week, there was a significant reduction in non-inflammatory lesions. (Figure 1A).

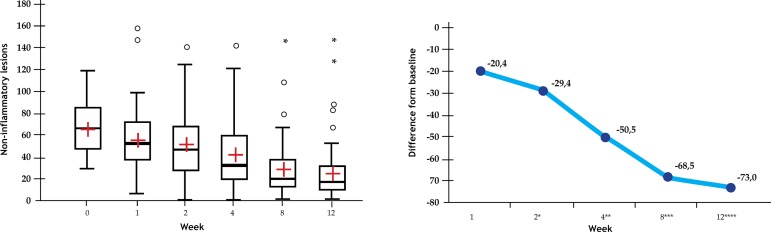

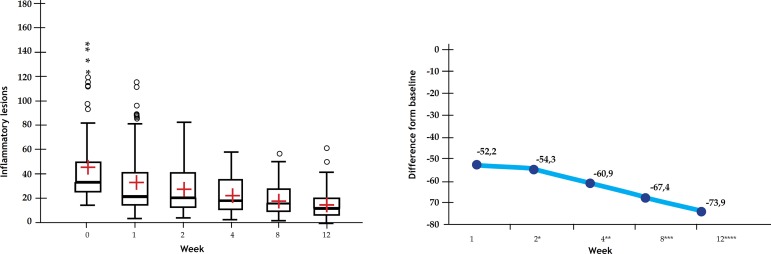

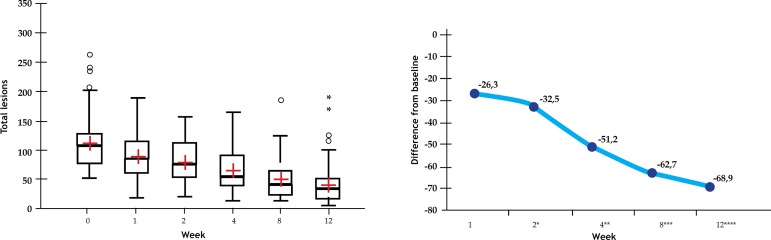

Figure 1.

Effect of combined therapy on the number of lesions. a.Chart showing the reduction in the number of noninflammatory lesions. b.Chart illustrating the reduction in the number of inflammatory lesions. c.Chart illustrating the reduction in the number of total lesions

1A.

Box-plots (chart on the left) and percentage of median change from baseline (chart on the right) in the number of noninflammatory lesions

1B.

Box-plots (chart on the left) and percentage of median change from baseline (chart on the right) in the number of inflammatory lesions.

1C.

Box-plots (chart on the left) and percentage of median change from baseline (chart on the right) in the number of total lesions

* Statistically significant differences when compared with results at week 0

** Statistically significant differences when compared with results at week 0 and 1.

*** Statistically significant differences when compared to results from week 0 to 2 .

**** Statistically significant differences when compared to results from week 0 to 4 (Friedman; p < 0.001).

There was gradual reduction in non-inflammatory lesions in relation to the initial visit: in week 2 the median decreased by 29.4%; at week 4 the decrease was of 50.5%; at week 8, 68.5%; and at week 12, around 73% (Figure 1A).

Considering inflammatory lesions, at week 1 the median of lesions decreased 52.2%; in week 2, the median decreased 54.3%; in week 4, 60.9%; in week 8, 67.4%; and in the last week, 73.7% (Figure 1B).

Regarding total number of lesions, in the first week there was a reduction of 26.3%; in the second week, the reduction was of 32.5%; in the fourth week, 51.2%; in the eighth week, 62.7%; and in the last week, 68, 9% (Figure 1C).

• Percentage of patients with reduction of at least 50% in the number of lesion:

Frequency and percentage of patients achieving reduction of at least 50% of inflammatory, noninflammatory and total lesions at week 12 were calculated. Fifty-five patients (75.3%) had a reduction of >50% in noninflammatory lesions; 51 patients (69.9%) in inflammatory lesions; and 57 patients (78.1%) in total lesions.

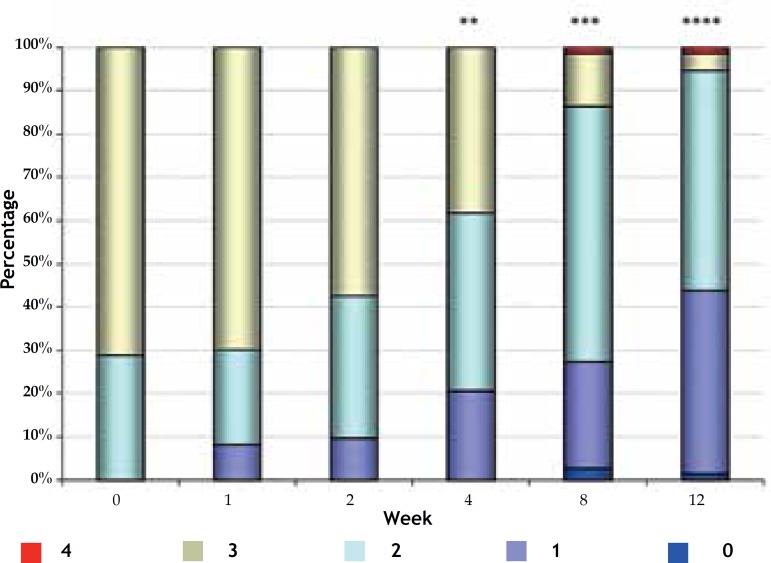

- Severity of facial acne:

At baseline, the maximum degree of severity was 3, observed in 52 patients (71.2%). From the second week, there was a significant decrease in the severity of acne (Friedman; p <0.001) (Figure 2). It was observed a greater reduction already from week 4, with 38.4% of patients with grade 3 acne, reaching just 4.1% (3 patients) at week 12.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the severity of acne (distribution of patients in percentage) in weeks of treatment

Facial acne severity was eva;uated fpllowing the scale below:

0 No lesions, just presenting erythema or residual hyperpigmentation

1 Presence of a few comedones and a few small papules and pustules

2 Presence of some comedones, papules and pustules. No nodule present

3 Presence of many comedones, papules and pustules. One nodule may be present

4 Covered with comedones, numerous papules and pustules. Presence of few nodules and cysts

5 Highly infammatory acne covering the face, with nodules and cysts present

* Statistically significant differences when compared with results at week 0.

** Statistically significant differences when compared with results at week 0 and 1.

*** Statistically significant differences when compared with results from week 0 to 2 .

**** Statistically significant differences when compared with results from week 0 to 4 (Friedman; p <0.001)

- Assessment of overall improvement according to the investigator:

Of the 73 patients, 64 (87.6%) had an improvement from satisfactory to excellent: 26 (35.6%) were excellent, 26 (35.6%) were good and 12 (16.4%) were satisfactory. Considering these results, 52 patients (71.2%) showed improvement from good to excellent. Moreover, the number of patients who had low or no improvement was 9 (12.4%): 8 had improvement <25% and only one showed no change from baseline.

- Evaluation of improvement and satisfaction according to the patient:

To the question asked in the week 12 "how do you feel from the start of the treatment?", 54 patients (74%) responded "much better", 15 (20.5%) answered "a little better", 4 (5.5 %) patients answered "equal" and no patient declared feeling worse.

Of the 73 patients, 69 (94.5%) were satisfied or very satisfied with the treatment. Only 4 participants (5.5%) declared to feel a little satisfied or dissatisfied.

- Safety and tolerability assessment:

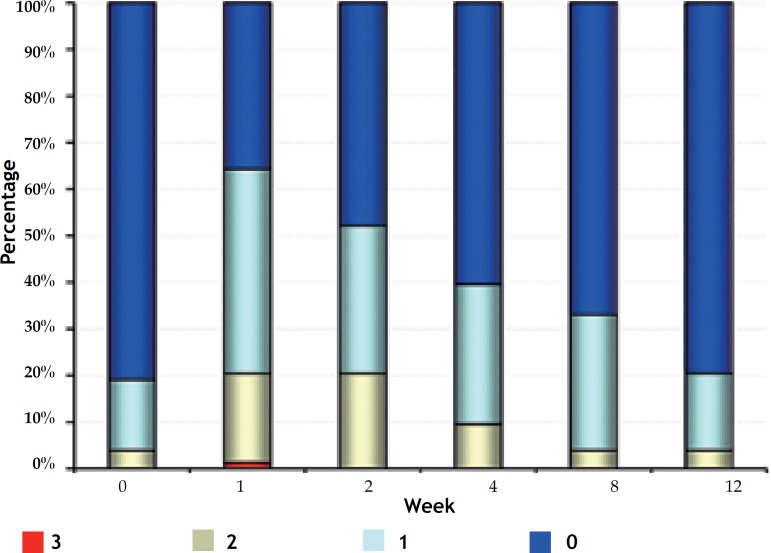

Erythema:

At baseline, most of the 59 patients (80.8%) had no erythema, 11 (15.1%) had mild erythema and 3 (4.1%) had moderate erythema.

In week 1, proportions changed, and an increase in the number of patients with erythema was observed: mild in 32 (43.8%), moderate in 14 (19.2%) and severe in 1 (1.4%) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients for the evaluation of A. Erythema; B. Burning; C. Dryness C; D. Scaling

Figure 3A.

Erythema evaluation

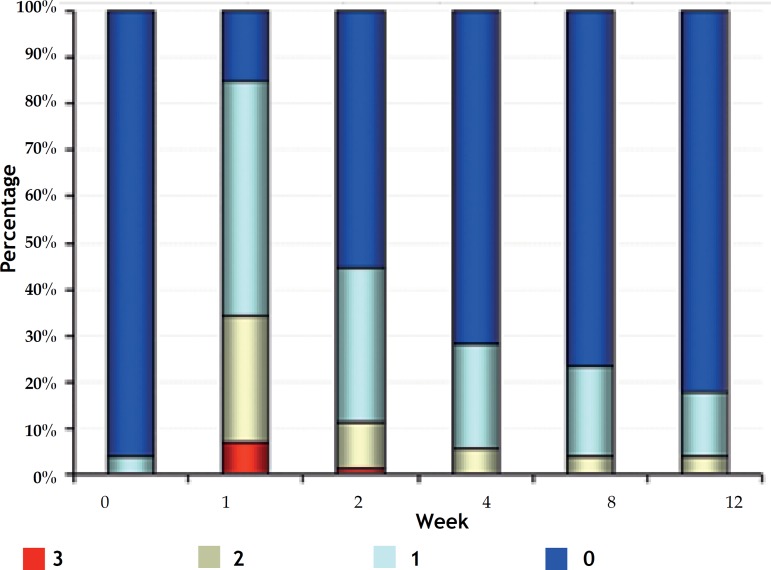

Figure 3B.

Burning evaluation

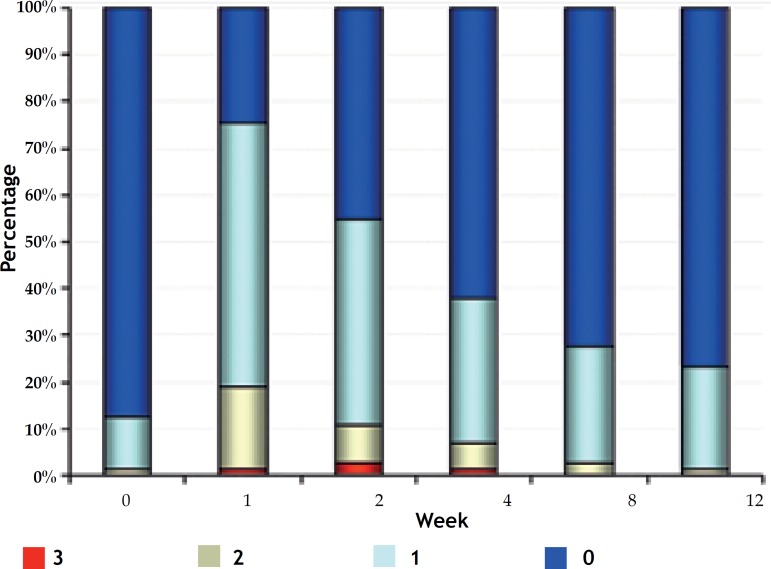

Figure 3C.

Dryness evaluation

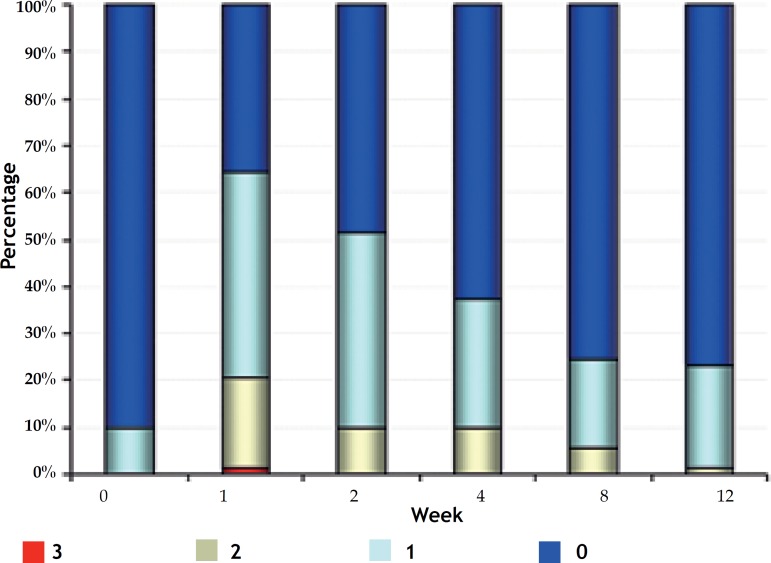

Figure 3D.

Scaling evaluation

From week 2, the number of patients with erythema decreased progressively, and it was observed, at week 12, only 3 (4.1%) patients with moderate erythema, 12 (16.4%) with mild and, what is more important, 58 (79.5%) with no erythema: values very similar to the baseline visit.

Presence of erythema at weeks 0 and 12 were significantly lower than at weeks 1 and 2, and erythema at weeks 4 and 8 was significantly lower compared to week 1 (Q Cochran; p <0.001).

Burning:

We observed that, at week 0, 70 patients (95.9%) did not report burning and only 3 (4.1%) reported mild burning. But at week 1, after starting the treatment, the number of patients with burning increased: 37 (50.7%) described as mild; 20 (27.4%) as moderate; and 5 (6.8%) as severe. (Figure 3B). Presence of burning at weeks 2, 4, 8 and 12 was significantly lower than in week 1 (Q Cochran; p <0.001). At weeks 8 and 12, percentage of patients without burning reached 80% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequencies and percentages for the evaluation of erythema, burning sensation, dryness and peeling

| Variable | Category | Week | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0** | 1 | 2 | 4* | 8* | 12** | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Erythema | Absent | 59 | 80.8 | 26 | 35.6 | 35 | 47.9 | 44 | 60.3 | 49 | 67.1 | 58 | 79.5 |

| Present | 14 | 19.2 | 47 | 64.4 | 38 | 52.1 | 29 | 39.7 | 24 | 32.9 | 15 | 20.5 | |

| Total | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | |

| 0 | 1 | 2* | 4* | 8* | 12* | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Burning | Absent | 70 | 95.9 | 11 | 15.1 | 40 | 55.6 | 51 | 71.8 | 56 | 76.7 | 60 | 82.2 |

| Present | 3 | 4.1 | 62 | 84.9 | 32 | 44.4 | 20 | 28.2 | 17 | 23.3 | 13 | 17.8 | |

| Total | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 72 | 100.0 | 71 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | |

| 0** | 1 | 2 | 4* | 8** | 12** | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Dryness | Absent | 64 | 87.7 | 18 | 24.7 | 33 | 45.2 | 44 | 62.0 | 53 | 72.6 | 56 | 76.7 |

| Present | 9 | 12.3 | 55 | 75.3 | 40 | 54.8 | 27 | 38.0 | 20 | 27.4 | 17 | 23.3 | |

| Total | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 71 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | |

| 0* | 1 | 2 | 4* | 8* | 12* | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Scaling | Absent | 65 | 90.3 | 26 | 35.6 | 35 | 48.6 | 45 | 62.5 | 55 | 75.3 | 56 | 76.7 |

| Present | 7 | 9.7 | 47 | 64.4 | 37 | 51.4 | 27 | 37.5 | 18 | 24.7 | 17 | 23.3 | |

| Total | 72 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 72 | 100.0 | 72 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | |

Statistically significant differences when compared with the results in week 1

Statistically significant differences when compared with the results in week 1 and 2 (Cochran test).

Dryness:

At baseline, of the 73 patients, 8 (11%) had mild dryness, 1 (1.4%) had moderate dryness and most patients, 64 (87.7%), had no dryness. A week after the beginning of the treatment, the number of patients with mild dryness increased to 41 (56.2%); 13 (17.8%) patients presented moderate dryness; and 1 (1.4%) patient had severe dryness (Figure 3C). Presence of dryness at weeks 0, 8 and 12 was significantly lower compared to weeks 1 and 2. At week 4, dryness was statistically lower than at week 1 (Q Cochran; p <0.001).

• Scaling:

Similar to burning, dryness and erythema at baseline, most of patients, 65 (89%) showed no scaling, and 7 (9.6%) had mild scaling. At week 1, the number of patients with scaling increased: 32 (43.8%) patients presented mild scaling, 14 (19.2%) had moderate and 1 (1.4%) had severe scaling (Figure 3D). Equally to the other parameters evaluated, there was a reduction in the number of patients with scaling along the weeks, and the decrease was statistically significant at weeks 0, 4, 8 and 12 when compared with week 1 (Q Cochran; p <0.001).

• Satisfaction questionnaire:

- To the question, "were you uncomfortable with the adverse events of the treatment?": 38 patients (52.1%) answered "not at all uncomfortable", 34 (46.6%) answered "a little uncomfortable" and 1 (1.4 %) answered "uncomfortable".

- To the question, "was it easy to incorporate the treatment regimen in your daily life": 43 patients (58.9%) strongly agreed, 28 (38.4%) agreed and 2 (2.7%) disagreed.

- Compared with other treatments for acne used by patients, 52 (75.4%) found the study treatment "much better", 13 (18.8%) "a little better", 3 (4.3%) "equal", and 1 (1.4%) "a little worse".

- 69 patients (94.5%) stated they would like to use this treatment again and 4 (5.5%) declared they would not like.

• Adverse events:

More than half of the sample - 45 patients (61.6%) - presented some adverse event. All events were defined as not serious and no patient discontinued treatment because of this. Only 2 patients had events related to the study: the first presented bruise on the face and the second, eczema. Both have improved completely without sequelae. Among other adverse events, the most frequent were headache and common cold, but they were unrelated to therapy.

DISCUSSION

In several studies, the association of adapalene 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel was more effective in reducing noninflammatory, inflammatory and total lesions compared with both in monotherapy.15,16 The association of the 2 molecules shown to be synergistic (the efficacy score of the combination was higher than the sum of the efficacy scores of each one in monotherapy). 14,17,20 In these studies, the onset of action was fast, resulting in a significant reduction in the number of noninflammatory, inflammatory and total lesions, from week 1 of treatment.14,15,16,17 In our case series, we observed that the decrease in inflammatory and total lesions was also significant from week 1, but for the noninflammatory lesions, the reduction was seen only from week 2.

As described in the literature, we found that the percentage of reduction in the number of lesions (noninflammatory, inflammatory and total) is maintained and progressive over the 12 weeks, reaching 73.9% for inflammatory, 73% for noninflammatory and 68.9% for total lesions in the last visit (Figures 4, 5 and 6). Thus, at week 12 the number of lesions was still decreasing. To obtain the proportion of patients who would have a good response to treatment in terms of efficacy, we calculated the percentage of patients with a reduction ≥50% in the number of noninflammatory, inflammatory and total lesions in week 12. We observed that 75.3% of patients had a reduction ≥50% in noninflammatory lesions, 69.9% patients had a reduction in inflammatory lesions and 78% had a reduction in total lesions, which confirms the results obtained from the percentage of patients who had an overall improvement from good to excellent (71.2%).

Figure 4.

Patient photographed at baseline and at week 12 after initiation of treatment

Figure 5.

Patient photographed at baseline and at 12 weeks after initiation of treatment

Figure 6.

Patient photographed at baseline and at 12 weeks after initiation of treatment

In accordance with the studies in the literature, the drug was well tolerated and safe. 19 Erythema, burning, scaling and dryness emerged during the first week of treatment, and they were mild in most patients, with a progressive reduction from week 2. No patient discontinued treatment or left the study because of these adverse events. Considering the patient satisfaction questionnaire, these effects did not cause interference in the treatment and only had little or no discomfort. Most patients reported being satisfied with the results. The proposed regimen was easy to be incorporated into daily lives for most patients (98%) and 94.5% of patients would like to continue the therapy.

Acne is a multifactorial disease, with a major psychosocial impact. Dermatologists often have to prescribe several medications at the same time to achieve better results. However, the difficulty in properly following a medical prescription is frequent, due to lack of time or difficulty with the schedule, making the results to be not as expected in terms of effectiveness, leading to interruption and abandonment of treatment. All this may affect self-esteem, often leading to psychological problems.21

The fact that the association of adapalene and benzoyl peroxide gel is synergistic increases the therapeutic efficacy, which seems to allow an improvement in patient adherence to treatment, as suggested by our case series, since we had 92.4% of included patients still participating in the end of the study. Thus, with rapid results, patient is encouraged to comply with the treatment, making the benefits of therapy greater. A good clinical response and patient satisfaction with the treatment positively influence adherence to treatment. 22

In this study, it is evident the efficacy of the association of adapalene and benzoyl peroxide gel. This therapy proved to be a well-tolerated and safe option for the treatment of acne vulgaris in the Brazilian population. Other studies with longer follow-up and more patients will be important to observe the impact of this therapy in the quality of life of patients.

Footnotes

Study performed at Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual de São Paulo (HSPE); KOLderma Instituto de Pesquisa Clínica Ltda.; Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas; Hospital De Clínicas - Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPA); Serviço de Dermatologia do Ambulatório Magalhães Neto do Complexo HUPES - Universidade Federal da Bahia; Instituto de Dermatologia e Estética do Brasil Ltda. (IDERJ); Instituto da Pele, Goiânia/ GO.

Financial Support: Galderma do Brasil was the financial sponsor of the study.

Conflict of interest: Researchers received financial support from the company Galderma.

How to cite this article: Sittart JAS, Costa A, Mulinari-Brenner F, Follador I, Azulay-Abulafia L, Castro LCM. Multicenter study for efficacy and safety evaluation of a fixed-dose combination gel with adapalen 0,1% and benzoyl peroxide 2,5% (Epiduo) for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Brazilian population. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(6 Suppl 1):S01-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prevalence, morbidity, and cost of dermatologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:395–401. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12541101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunliffe WJ, Gould DJ. Prevalence of facial acne vulgaris in late adolescence and in adults. Br Med J. 1979;1:1109–1110. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6171.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawin H, Beylot C, Chivot M, Faure M, Poli F, Revuz J, et al. Physiopathology of acne vulgaris:recent data, new understanding of the treatments. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leyden JJ. A review of the use of combination therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S200–S210. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brogden RN, Goa KE. Adapalene: a review of its pharmacological properties and clinical potential in the management of mild to moderate acne. Drugs. 1997;53:511–519. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michel S, Jomard A, Démarchez M. Pharmacology of adapalene. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:3–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.1390s2003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waugh J, Noble S, Scott LJ. Adapalene: a review of its use in the treatament of acne vulgaris. Drugs. 2004;64:1465–1478. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464130-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiboutot D. Regulation of human sebaceous glands. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2004.t01-2-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jugeau S, Tenaud I, Knol AC, Jarrousse V, Quereux G, Khammari A, et al. Induction of tol-like receptors by P. Acnes. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1105–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenaud I, Khammari A, Dreno B. In vitro modulation of TLR-2, CD1d and IL-10 by adapalene on normal human skin and acne inflammatory lesions. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:500–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bikowsk JB. Mechanisms of the comedolytic and anti-inflamatory properties of topical retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tangetti E. The evolution of BPO therapy. Cutis. 2008;82:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leyden JJ. Current issues in antimicrobial therapy for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:51–55. doi: 10.1046/j.0926-9959.2001.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan J, Gollnick HP, Loesche C, Ma YM, Gold LS. Synergistic efficacy of adapalene 0,1% benzoyl peroxide 2,5% in the treatment of 3855 acne vulgaris patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:197–205. doi: 10.3109/09546631003681094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pariser DM, Westmoreland P, Morris A, Gold MH, Liu Y, Graeber M. Longterm safety and efficacy of a new fixed-dose combination of adap 0,1% and BPO for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:899–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiboutot DM, Weiss J, Bucko A, Eichenfield L, Jones T, Clark S, et al. Adapalenebenzoyl peroxide, a new fixed dose combination for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Results of a randomized, multicenter double-blind controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gollnick HP, Draelos Z, Glenn MJ, Rosoph LA, Kaszuba A, Cornelison R, Adapalene-BPO study group et al. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide, a unique fixeddose combination topical gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a transatlantic, randomized, double blind controlled study in 1670 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1180–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold LS, Tan J, Cruz-Santana A, Papp K, Poulin Y, Schlessinger J, et al. A North American study of adapalene-benzoyl peroxide combination gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2009;84:110–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loesche C, Pernin C, Poncet M. Adapalene0,1% and benzoyl peroxide 2,5% as fixed-dose combination gel is as well tolerated as the individual components in terms of cumulative irritancy. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:524–526. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kircicik LH. Synergy and its clinical relevance in topical acne therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:30–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaghloul SS, Cunliffe WJ, Goodfield MJ. Objective assessment of compliance with treatments in acne. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1015–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dréno B, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Finlay AY, Layton A, Leyden JJ, et al. Large-scale worldwide observational stugy of adherence with acne therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:448–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]