Abstract

Fluorescence is utilized as the output for a range of assay formats used in high-throughput screening (HTS). Interference with these assays from the compounds in libraries utilized in HTS is a well-recognized phenomenon, particularly for assays relying on UV excitation such as for direct detection of the oxidoreductase cofactors NADH or NADPH. In this study, we discuss these interference challenges and highlight the specific case of the diaphorase/resazurin system that can be coupled to enzymes utilizing NADH or NADPH. We review the utilization of this assay system in the literature and argue that the diaphorase/resazurin system is underutilized in assay development. It is the authors' hope that this Perspective and the accompanying Technical Brief in this issue will stimulate interest in a robust and sensitive coupling system to avoid assay fluorescence interference.

Fluorescence as a spectroscopic phenomenon is utilized as the output for a range of assay formats used in high-throughput screening (HTS). These include readouts such as fluorescence polarization (FP), analyte quantitation, cell viability, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, and high-content imaging applications. While the wavelength at which light emitted in many fluorescence-based assays can be “tuned”, many small molecules in a small molecule library are optically active and can interfere with assay performance. This interference can be either by absorbing and emitting light in the same window as the assay resulting in false-positive signal (fluorescing) or absorbing light at either the excitation or emission wavelengths resulting in attenuated intensity of signal (quenching).1 An HTS can utilize library compound concentrations at the upper end of 20–50 μM, well above the concentration of the fluorescent reporter in an assay (discussed by Dahlin et al.).2 To account for these artifacts, assessment of compound interferences using orthogonal and counter assays is critical to ensure that HTS hits are not due to the optical properties of the molecule. Following triage of false positives, “true” assay hits can be assessed with further biologically relevant assays.3,4

Understanding the extent of compound fluorescence within a library, and the spectroscopic window in which it occurs, can inform assay design and aid in avoiding significant false positives during the HTS phase. For example, Simeonov et al. profiled a library containing >70,000 compounds across a number of spectral regions that are regularly utilized in HTS.5 Fluorescence was compared against a range of fluorophore standards. For example, the standard dyes 4-MU (4-methylumbelliferone, hymecromone) and Alexa Fluor 350 excite at 340 nm and emit at 450 nm (Fig. 1). Of those compounds assessed, 5% (about 3,500 compounds) of the library produced fluorescence equivalent to 10 nM 4-MU or Alexa Fluor 350, and almost 2% of compounds (about 1,000) produced signal equivalent to 100 nM of the fluorophore standards–these are concentrations regularly utilized in fluorescent-based assays. At longer wavelengths, a far lower proportion of library was fluorescent (0.01%–0.1%), demonstrating that “redshifting” the fluorophore reporter during assay development can aid in reducing the number of false positives that arise due to spectroscopic artifacts from test compounds.

Fig. 1.

Spectral profiling of library compounds excited at 340 nm and fluorescing at 450 nm (the 4-MU/Alexa Fluor 350 spectral window). (A) Cumulative spectroscopic profiling results for >70,000 compounds on a well-by-well basis, showing a strong concentration-dependent increase in fluorescent signal (i.e., greater fluorescence at higher concentrations of a given compound). Fluorescent samples are shown in purple, inconclusive samples (weakly fluorescent) are shown in orange, and nonfluorescent samples are shown in gray. (B) Compound library SOM based on the structural similarity of compounds in the library, with fluorescent activity in the 4-MU window, is overlaid. The hexagons (clusters) in each SOM are colored by the enrichment level of fluorescent compounds in that cluster. A cluster with a dark color is significantly enriched in fluorescent compounds compared to the library average, and a green cluster has no fluorescent compounds. It can be seen that groups of structurally similar compounds in the library are likely to fluoresce, suggesting that the chemotype clustering in HTS hit analysis can point to “repeat offenders” in an HTS compound library. (C) A fluorescence profile across 39 quantitative HTS assays is shown, where the fraction of fluorescent compounds out of all actives identified in each screen is plotted. Reprinted with permission from Ref.5 Blue-fluorescent compounds represent about 5% of the library assessed, but in assays run in the blue window (4-MU window, excitation = 340 nm and emission = 450), nearly 50% of the active compounds were fluorescent, which is nearly a 10-fold enrichment. HTS, high-throughput screening; SOM, self-organizing map; 4-MU, 4-methylumbelliferone.

The relevance of the data relating to 4-MU and Alexa Fluor 350 lies in the fact that it is the same optical window used to measure the fluorescence of the common substrates NADH and NADPH in biochemical assays. The seminal work of Britton Chance and colleagues from the 1950s onward demonstrated that tissues and cells excited by UV light emit blue fluorescence (termed tissue autofluorescence) and that this is due to NADH and NADPH (predominately in the mitochondria).6 NADH and NADPH (collectively termed NAD(P)H) share almost identical excitation (340 ± 30 nm) and emission (460 ± 50 nm) windows,7 and just as importantly, NAD+ and NADP+ are not optically active in the same window. As NAD(P)H are cofactors for a range of oxidoreductases, one can readily identify probes modulating enzymatic activity through the measurement of consumption or production NAD(P)H (depending on the direction of the biochemical reaction),8 and in kinetic mode or at an endpoint. A number of advantages to this strategy exist, including the fact that the native biochemical reaction can be performed without modification.

Based on the issue with blue-shifted screening library probes discussed above, one might anticipate that directly measuring NAD(P)H in an HTS produces a significant number of false-positive hits, and just as worrying, might produce false-negative data that results in loss of potentially tractable hits. This is indeed the case. In their analysis, Simeonov et al. examined 39 screens that had previously been performed at their center and assessed the fraction of active compounds likely to have been fluorescent, which was particularly significant for fluorescence-based assays that excited in the UV range.5 For example, an oxidoreductase biochemical assay that measured the production of NADH (gain of fluorescence) produced a series of 28 compounds that shared a core structure. However, it was found that 23 of these hits (80%) were fluorescent upon excitation with UV light. Similar compounds ranked as inactive in the HTS were not fluorescent (or were weakly fluorescent), and orthogonal assays against the same target revealed that the initial fluorescent assay hits were indeed inactive false positives. This is a significant issue when one considers the range of oxidoreductases screened using this assay strategy. A sample list of dehydrogenases and enzymes coupled to dehydrogenases is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reported High-Throughput Screening Campaigns and Assays that Incorporated the Diaphorase/Resazurin Reaction for the Assay Readout

| Enzyme | Reaction direction | Couple | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1) | NADP+ to NADPH | Diaphorase | 16,25 |

| Mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase (mIDH1) | NADPH to NADP+ | Diaphorase | 16,25 |

| Plasmodium falciparum glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase 6-phosphogluconolactonase | NADP+ to NADPH | Diaphorase | 15 |

| Giardia lamblia fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (FBPA) | NAD+ to NADH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, triose phosphate isomerase, Diaphorase | 26 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) | NADPH to NADP+ | Diaphorase | 27 |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) | NADP+ to NADPH | Diaphorase | 28 |

| Glucokinase (GCK) | NADP+ to NADPH | Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, Diaphorase | 17 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | NAD+ to NADH | Diaphorase | 29 |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase 5A1 (ALDH5A1) | NADP+ to NADPH | Diaphorase | 30 |

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | NAD+ to NADH | Diaphorase | 31 |

| Phosphomannose isomerase | NADP+ to NADPH | Phosphoglucose isomerase, Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, Diaphorase | 32 |

For each enzyme target, the reaction direction of the coupling enzyme is listed (reaction direction). The “Couple” for each assay lists any enzymes used for coupling between the target enzyme and the final fluorescence readout.

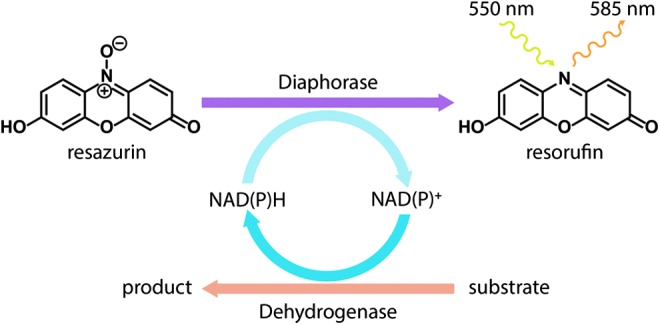

In this issue, Davis et al. provide a detailed protocol for coupling a given NAD(P)H-dependent enzyme of interest to a second enzyme reporter system, diaphorase/resazurin, to quantify the concentration of NAD or NADPH present in a biochemical assay (Fig. 2).9 In effect, this strategy redshifts the assay, avoiding the optical activity of a significant proportion of the screening library. The term “diaphorase” is a generic term for any oxidoreductase enzyme that can utilize either NADH or NADPH to catalyze the reduction of dyes (chromogenic electron acceptors),10 including commonly used cell-based viability reporters such as MTT and methylene blue. The form of diaphorase commonly utilized in HTS assays is purified from Clostridium kluyveri, although other diaphorases have been purified and reported also.11 Diaphorase was first reported to reduce the weakly-fluorescent resazurin (also known as Alamar Blue) to the highly fluorescent resorufin as a means of measuring the activity of dehydrogenases by Guilbalt and Kramer in 1964 and 1965.12,13 One possible advantage of coupling diaphorase in an oxidoreductase HTS is that if NAD(P)H is the product it is consumed by diaphorase and this prevents the enzyme running in the “reverse” direction. Despite the advantages of redshifting NAD(P)H detection, the diaphorase/resazurin assay does not appear to have been greatly utilized over the past 50 years (only 29 articles appear in PubMed with the terms “diaphorase” and “resazurin”).

Fig. 2.

Schematic conveying diaphorase/resazurin coupling in HTS assays. A generic dehydrogenase converts substrate to product, converting NAD+ to NADH or NADP+ to NADPH. Diaphorase utilizes the resulting NADH or NADPH (excitation 340 nm, emission 460 nm) as the electron source for reducing resazurin (weakly fluorescent) to the fluorescent product resorufin (excitation 550 nm, emission 585 nm), allowing the excitation and emission to be “redshifted.”

The diaphorase/resazurin assay has been adopted for HTS in a number of ways, and the first example in HTS appears to have been reported in 2005.14 Direct coupling of diaphorase was reported in an HTS for inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase 6-phosphogluconolactonase to measure production of NADPH as a result of the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to 6-phosphoglucono-δ-lactone produced.15 Conversely, mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1 R132H) consumes NADPH in converting α-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate, measuring the loss of NADPH over time monitored using diaphorase.16 Diaphorase can also be used as a reporter for a nondehydrogenase biochemical assay, by enzymatic coupling to the enzyme of interest. For example, glucokinase (GCK) is a diabetes target that converts glucose to glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), and its activity is tightly regulated by glucokinase regulatory protein (GKRP). To link to diaphorase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) that converts G6P and NAD+ to 6-phosphogluconate and NADH, respectively, was used. The NADH produced is then detected using the diaphorase/resazurin system.17

In each of the three HTS cases mentioned above, orthogonal assays with HTS hits screened against the diaphorase/resazurin alone were needed to triage false-positive compounds that inhibited/interfered with the reporter assay. While few compounds in a high-quality screening library would share resorufin's optical properties, this can be easily assessed when following up on hits by performing a “preread” after pin-transferring compound, but before initiating the biochemical reaction. The opposite risk is that hits are quenching fluorescence signal (through absorbing, exciting, or emitting light), and assessing the hit compounds in the presence of resorufin alone can identify these false-positive compounds. Anecdotally, it appears that the false-negative hit rate is relatively low compared with direct measurement of NAD(P)H levels. A systematic profiling effort of an HTS library against diaphorase/resazurin needs to be carried out, similar to those reported for other assay readouts such as luciferase and fluorescence,5,18 to fully understand library interference for this assay.

Other fluorescence assay artifacts also exist that are equally confounding and not so readily resolved through assay modification. Library compounds can interfere with fluorescence signal through the “inner filter effect” by absorbing emitted light, particularly at higher concentrations. The library compound inner filter effect can be mitigated by performing a “preread” measuring the absorbance of the compounds at the excitation and emission wavelengths of the fluorophore used in the assay to identify possible interference.19 Fluorophores with conjugated planar systems can also confound assay design through dimer (and multimer) formation.1 The rhodamine dyes are such a family that can form dimers through noncovalent self-association.20,21 Dimerization results in a spectral shift, with a consequent change in fluorescence intensity. FP assays also meet with interferences,22 including spectral interference (interference with the detection of fluorescence polarized light signal), particularly when low concentrations of labeled ligand are used in an assay. FP assays can be redshifted during assay development by assessing dyes that avoid blue-shifted assay library interference. For example, a study developing inhibitors for the interaction between Vitamin D Receptor and Steroid Receptor Coactivator 2 utilized an Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated peptide specifically to avoid library fluorescence interference.23,24 It is important to emphasize that fluorescent compounds may indeed be active in an HTS; an FP study seeking inhibitors of calcium-bound S100B reexamined fluorescent hits that were initially triaged, and found that they were in fact active in orthogonal assays.

All fluorescence assays have their own unique challenges for assay design that can generally be accounted for thorough careful consideration of counter screens and orthogonal assays. In our experience, the diaphorase/resazurin system for measuring NAD(P)H levels appears to be a highly useful coupling strategy that improves assay quality by decreasing library interference and improving sensitivity. It should be pointed out that while diaphorase is now being incorporated into HTS protocols, no systematic data exists to make the conclusion that the diaphorase assay is superior to the direct NAD(P)H assay in practice, although the accompanying protocol in this issue does partially address this issue. Furthermore, the reagents are not exceedingly costly, and so can be adopted relatively easily. It is our hope that the information in this perspective and the accompanying protocol will encourage its utilization in other screening centers.

Abbreviations Used

- 4-MU

4-methylumbelliferone

- FP

fluorescence polarization

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- SOM

self-organizing map

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kyle Brimacombe for designing Figure 2. This work was supported by the NCATS Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Simeonov A, Davis MI: Interference with fluorescence and absorbance. In: Assay Guidance Manual. Sittampalam GS, Coussens NP, Nelson H, et al. (eds.) Bethesda, MD, 2015: Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343429 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahlin JL, Nissink JW, Strasser JM, et al. : PAINS in the assay: chemical mechanisms of assay interference and promiscuous enzymatic inhibition observed during a sulfhydryl-scavenging HTS. J Med Chem 2015;58:2091–2113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, et al. : Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:11473–11478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jadhav A, Ferreira RS, Klumpp C, et al. : Quantitative analyses of aggregation, autofluorescence, and reactivity artifacts in a screen for inhibitors of a thiol protease. J Med Chem 2010;53:37–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Thomas CJ, et al. : Fluorescence spectroscopic profiling of compound libraries. J Med Chem 2008;51:2363–2371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croce AC, Bottiroli G: Autofluorescence spectroscopy and imaging: a tool for biomedical research and diagnosis. Eur J Histochem 2014;58:2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Ruyck J, Famerée M, Wouters J, Perpète EA, Preat J, Jacquemin D: Towards the understanding of the absorption spectra of NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ as a common indicator of dehydrogenase enzymatic activity. Chem Phys Lett 2007;450:119–122 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowry OH, Roberts NR, Kapphahn JI: The fluorometric measurement of pyridine nucleotides. J Biol Chem 1957;224:1047–1064 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MI, Shen M, Simeonov A, Hall MD: Diaphorase coupling protocols for red-shifting dehydrogenase assays. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2016;14:207–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boethling RS, Weaver TL: A new assay for diaphorase activity in reagent formulations, based on the reduction of thiazolyl blue. Clin Chem 1979;25:2040–2042 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horie S: Advances in research on DT-diaphorase—catalytic properties, regulation of activity and significance in the detoxication of foreign compounds. Kitasato Arch Exp Med 1990;63:11–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guilbault GG, Kramer DN: New direct fluorometric method for measuring dehydrogenase activity. Anal Chem 1964;36:2497–2498 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guilbault GG, Kramer DN: Fluorometric procedure for measuring the activity of dehydrogenases. Anal Chem 1965;37:1219–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bembenek ME, Kuhn E, Mallender WD, Pullen L, Li P, Parsons T: A fluorescence-based coupling reaction for monitoring the activity of recombinant human NAD synthetase. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2005;3:533–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Preuss J, Hedrick M, Sergienko E, et al. : High-throughput screening for small-molecule inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase 6-phosphogluconolactonase. J Biomol Screen 2012;17:738–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis MI, Gross S, Shen M, et al. : Biochemical, cellular, and biophysical characterization of a potent inhibitor of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase IDH1. J Biol Chem 2014;289:13717–13725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rees MG, Davis MI, Shen M, et al. : A panel of diverse assays to interrogate the interaction between glucokinase and glucokinase regulatory protein, two vital proteins in human disease. PloS One 2014;9:e89335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auld DS, Southall NT, Jadhav A, et al. : Characterization of chemical libraries for luciferase inhibitory activity. J Med Chem 2008;51:2372–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betzi S, Alam R, Martin M, et al. : Discovery of a potential allosteric ligand binding site in CDK2. ACS Chem Biol 2011;6:492–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burghardt TP, Lyke JE, Ajtai K: Fluorescence emission and anisotropy from rhodamine dimers. Biophys Chem 1996;59:119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernando J, van der Schaaf M, van Dijk EMHP, Sauer M, García-Parajó MF, van Hulst NF: Excitonic Behavior of Rhodamine Dimers: A Single-Molecule Study. J Phys Chem A 2003;107:43–52 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall MD, Yasgar A, Peryea T, et al. : Fluorescence polarization assays in high-throughput screening and drug discovery. Methods Appl Fluorescence 2016;in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandhikonda P, Lynt WZ, McCallum MM, et al. : Discovery of the first irreversible small molecule inhibitors of the interaction between the vitamin D receptor and coactivators. J Med Chem 2012;55:4640–4651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teichert A, Arnold LA, Otieno S, et al. : Quantification of the vitamin D receptor–coregulator interaction. Biochemistry 2009;48:1454–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popovici-Muller J, Saunders JO, Salituro FG, et al. : Discovery of the first potent inhibitors of mutant IDH1 that lower tumor 2-HG in vivo. ACS Med Chem Lett 2012;3:850–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Information: NCfB. PubChem BioAssay Database; AID = 2451, Source = University of Maryland, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioassay/2451#section=Top (Last accessed on Jan. 9, 2016)

- 27.Kumar A, Zhang M, Zhu L, et al. : High-throughput Screening and Sensitized Bacteria Identify an M. tuberculosis Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitor with Whole Cell Activity. PloS One 2012;7:e39961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preuss J, Richardson AD, Pinkerton A, et al. : Identification and characterization of novel human glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase inhibitors. J Biomol Screen 2013;18:286–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li W, Sauve A: NAD+ Content and Its Role in Mitochondria. In: Mitochondrial Regulation. Vol 1241 Palmeira CM, Rolo AP. (eds.), pp. 39–48. Springer, New York, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ippolito JE, Piwnica-Worms D: A fluorescence-coupled assay for gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) reveals metabolic stress-induced modulation of GABA content in neuroendocrine cancer. PloS One 2014;9:e88667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duveau DY, Yasgar A, Wang Y, et al. : Structure-activity relationship studies and biological characterization of human NAD(+)-dependent 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2014;24:630–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahl R, Bravo Y, Sharma V, et al. : Potent, selective, and orally available benzoisothiazolone phosphomannose isomerase inhibitors as probes for congenital disorder of glycosylation Ia. J Med Chem 2011;54:3661–3668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]