Abstract

Vitamin K (VK) is a fat-soluble vitamin whose deficiency disrupts coagulation and may disturb bone and cardiovascular health. However, the scale and systems affected by VK deficiency in pediatric populations remains unclear. We conducted a study of the plasma proteome of 500 Nepalese children 6–8 years of age (male/female ratio = 0.99) to identify proteins associated with VK status. We measured the concentrations of plasma lipids and protein induced by VK absence-II (PIVKA-II) and correlated relative abundance of proteins quantified by mass spectrometry with PIVKA-II. VK deficiency (PIVKA-II >2 μg/L) was associated with a higher abundance of low-density lipoproteins, total cholesterol, and triglyceride concentrations (p < 0.01). Among 978 proteins observed in >10% of the children, five proteins were associated with PIVKA-II and seven proteins were differentially abundant between VK deficient versus sufficient children, including coagulation factor-II, hemoglobin, and vascular endothelial cadherin, passing a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 10% (q < 0.10). Among 27 proteins associated with PIVKA-II or VK deficiency at a less stringent FDR (q < 0.20), a network comprised of hemoglobin subunits and erythrocyte anti-oxidative enzymes were highly and positively correlated each other (all r > 0.7). Untargeted proteomics offers a novel systems approach to elucidating biological processes of coagulation, vascularization, and erythrocyte oxidative stress related to VK status. The results may help elucidate subclinical metabolic disturbances related to VK deficiency in populations.

Introduction

Vitamin K (VK) is a fat-soluble micronutrient, known primarily for its function in blood coagulation (FAO/WHO, 2002). Relatively little public health attention has been paid to vitamin K status and its health effects, mainly because hemorrhaging, a clinical manifestation of vitamin K deficiency (VKD), is rare in healthy populations (Suttie, 2009). However, there is evidence that young infants have a risk of VKD bleeding, especially among exclusively breast-fed infants not receiving VK prophylaxis at birth in disadvantaged populations (Shearer, 2009).

A growing number of studies have shown that low vitamin K intake or plasma concentration is associated with increased risk of aging-related health outcomes including cardiovascular diseases, hip fractures, insulin resistance, inflammation, and cognitive impairment in adult and elderly populations (Booth, 2009; Ferland, 2012a, 2012b; McCann and Ames, 2009). In addition, a sufficient number of studies have reported an association of VK status with markers of bone metabolism and bone mineral content, suggesting a role in bone health in growing children (Cashman, 2005; Kalkwarf et al., 2004; O'Connor et al., 2007). These findings collectively suggest that suboptimal VK status may be a public health problem that affects diverse health outcomes across the life stages beyond its classical functions in coagulation.

Vitamin K exerts its functions through a unique mechanism. Different from other fat-soluble vitamins, it serves as a cofactor of ϒ-glutamyl carboxylase that converts glutamic acid (Glu) residues into ϒ-carboxyglutamate (Gla) residues, allowing calcium-dependent conformational changes of VK-dependent proteins (VKDPs) (Stenflo et al., 1974; Suttie, 1980). The Gla residues have a profound role in the biological activity of VKDPs, as this post-translational modification promotes VKDP localization and binding to membranes where they exert their functions (Presnell and Stafford, 2002).

Of at least 15 VKDPs identified, 7 proteins are either blood coagulants (factor II, X, VII, and IX) or anti-coagulants (Protein C, S, and Z), all carboxylated in the liver (McCann and Ames, 2009). Some extrahepatic VKDPs are extracellular matrix proteins functioning as regulators of bone mineral maturation and inhibitors of calcification of smooth muscle or vascular endothelium, but the physiological functions of others remain elusive (Ferland, 2012a; McCann and Ames, 2009).

Among hepatic VKDPs, prothrombin (factor II) is the most well-characterized and abundant in circulation (Suttie, 2009). When the liver storage of VK is depleted, it secretes under-carboxylated prothrombin into plasma, which is called “protein induced by vitamin K absence-II” (PIVKA-II) (Hemker et al., 1970). Because prothrombin has 10 Gla residues, PIVKA-II can be in different forms, and only a few un-carboxylated glutamate residues can substantially reduce the coagulant activity of prothrombin (Esnouf and Prowse, 1977). This biologically nonfunctional form of prothrombin can be detected before the physiological function of the pro-coagulant pathway is disrupted, suggesting more sensitivity to subclinical VK status than prothrombin time, which is used to test blood clotting time (Suttie, 1992). Thus, plasma PIVKA-II has been used as an indicator of suboptimal vitamin K status (Dituri et al., 2012).

The plasma proteome may provide a unique opportunity to explore biological roles of vitamin K in populations. It is the most comprehensive proteome among human body fluid proteomes, containing not only classic proteins synthesized by the liver and secreted into the circulation, but also proteins leaked from many different types of extrahepatic tissues (Anderson and Anderson, 2002). We have previously shown that plasma proteomics reliably discerns proteins known to circulate in association with vitamin A, E, and D, selenium and copper and may uncover nutrient-associated biological pathways that to date have not been appreciated (Cole et al., 2013; Schulze et al., 2015; West et al., 2015). Although there is no known plasma carrier protein for vitamin K (Olson, 1984), a plasma proteome may reflect changes in VKDPs or homeostatic changes in the local tissue environment in response to suboptimal functions of VKDPs.

In this study, we attempted to identify proteins associated with subclinical VKD assessed by elevated plasma PIVKA-II. We previously reported that subclinical VKD exists in approximately 20% of undernourished, but otherwise relatively healthy, children living in rural Nepal where multiple micronutrient deficiencies are common (Schulze et al., 2014). The results of this study may help elucidate the biological processes and potential health consequences related to suboptimal vitamin K status in healthy populations.

Methods

Study design, participation, and sample collection

In 1999–2001, we carried out a community-based, cluster-randomized controlled trial of antenatal micronutrient supplementation to improve birth size and to reduce risk of low birth weight in the southern plains district of rural Sarlahi, Nepal (ClinicalTrials.gov:NCT0011527) (Christian et al., 2003). In 2006–2008, 3524 children 6–8 years of age, born to mothers who participated in the trial were followed-up for growth, nutrition, and health assessment. Details of the follow-up have been described elsewhere (Stewart et al., 2009a; Stewart et al., 2009b).

The following information was collected by field workers during home visits: ethnicity, household socioeconomic characteristics, child 7-day morbidity (number of days with particular symptoms), literacy, and past week dietary intake (frequency of consumption of key foods). Trained anthropometrists measured height, weight, and mid-upper arm circumference using previously reported methods (Stewart et al., 2009a). Early morning venous blood samples (10 mL in sodium heparin-containing tubes without preservatives or antioxidants) were collected by phlebotomists, brought to a field laboratory and centrifuged. Blood plasma was aliquoted, immediately frozen under liquid nitrogen, shipped to the Johns Hopkins University Center for Human Nutrition, and stored at −80°C for future laboratory analysis.

Details of specimen selection for proteomics assessment protocol have been described (Cole et al., 2013; West et al., 2015). Of the 3305 children whose blood samples were obtained, 2130 children had the full four aliquots of plasma specimens, birth weight measured within 72 hours after birth, and complete epidemiological data from both the original trial and follow-up study. Among them, 1000 children were randomly sampled for micronutrient assessment. Finally, 500 of those children—balanced across maternal intervention groups—were randomly selected for the proteomics analysis.

Ethics, consent and permissions

Study field staff explained the research purpose, activities and risks of participation to mothers of eligible children and obtained oral informed consent during the child follow-up household visits (Stewart et al., 2009a; 2009b). The follow-up study including biospecimen collection and laboratory assessments received ethical approval from the institutional review board (IRB) at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA and the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Assessment of protein induced by Vitamin K absence-II (PIVKA-II), lipids, and inflammatory markers

PIVKA-II in plasma samples was quantified using an adaptation of a commercial enzyme immunoassay (i.e., more low concentration standards were added to improve resolution at low concentrations) (ASSERACHROM, Diagnostica Stago, France). The inter-assay coefficient of variability (CV) was 15.0% for a quality control pool at 3.3 μg/L, designed to be close to the cutoff for VKD. PIVKA-II concentration values less than 0.001 μg/L were undetectable (n = 26), leaving 474 plasma samples available for analysis with a continuous outcome. Details of lipid profiles (total cholesterol, high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides) and inflammation markers (C-reactive protein and α-1-acid glycoprotein) assessment have been reported elsewhere (Schulze et al., 2014; Stewart et al., 2009b).

Plasma proteomics assays

Quantitative proteomic analysis of these plasma samples has been reported in detail elsewhere (Cole et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2015; West et al., 2015). Briefly, plasma samples from each of the 500 participants randomly chosen for proteomics evaluation were immunoaffinity-depleted of six high abundance proteins using a Multiple Affinity Removal System LC column-Human 6 (Agilent Technologies). Depleted protein extracts went through overnight trypsin digestion and were labeled in random order with isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) 8-plex reagents (AB Sciex).

The samples were mixed and fractionated by strong cation exchange chromatography and analyzed on a LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (MS) (ThermoScientific, www.thermo.com/orbitrap). MS/MS spectra were extracted using Thermo Scientific Xtract software. All spectra data was searched with Proteome Discoverer software (v1.3, Thermo Scientific) against the RefSeq database using the Mascot search algorithm (Matrix Science, v2.1). Data were obtained from 72 iTRAQ experiments and the average number of proteins per experiment was 589. A total of 4705 proteins were detected with varying missing values.

Statistical analysis

Estimation of relative abundance of proteins has been documented in detail elsewhere (Cole et al., 2013; Herbrich et al., 2013). Briefly, log 2 base transformed-reporter ion intensities were median normalized in a single iTRAQ experiment. We applied linear mixed effects models (LME) to combine the proteomics data from different experiments and to estimate the association of protein relative abundances with plasma PIVKA-II concentration. Because the distribution of PIVKA-II data was skewed to the right, we used log 2 base transformed plasma PIVKA-II data in the analysis. We fitted univariate random intercept models with PIVKA-II as a dependent variable and protein as an independent variable. Parameters were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood estimation.

From the LME model, the fixed effect of the slope of the PIVKA-II and protein association was summarized in tables and interpreted as percentage change in PIVKA-II associated with doubling of relative abundance of protein. The strength of association was denoted by p value. A false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected p value was computed and denoted as q in tables (Stroey, 2002). We considered proteins with q < 0.10 to be significantly associated with PIVKA-II or VKD. R2 refers to the proportion of variance explained by the fitted values of the nutrient:protein regression models (Robinson, 1991).

In addition, we categorized children into VKD (PIVKA-II >2 μg/L) and sufficient groups (PIVKA-II ≤2 μg/L) to identify proteins that may not be linearly associated with PIVKA-II concentration, but differentially abundant by VK status (Schulze et al., 2014). We built a correlation matrix with proteins associated with PIVKA-II or VKD passing a relaxed threshold of q less than 0.20 to explore potential biological pathways or metabolic networks among proteins associated with VK status. Correlation coefficients of pairwise protein:protein were calculated within each iTRAQ experiment and the averaged coefficients across iTRAQ experiments were used to construct a correlation matrix. The dataset of plasma PIVKA-II concentrations and relative abundance of proteins is available in Supplementary Table S1 (supplementary material is available online at www.liebertpub.com/omi). All analyses were carried out using in-house-developed open source software implemented in the statistical environment R (R Development Core Team, 2013).

Results

The median (interquartile range) of plasma PIVKA-II concentration was 1.31 (0.83, 1.87), ranging from 0 to 13.0 μg/L. Demographic, anthropometric, household, dietary, and health characteristics and lipid and inflammatory profiles of children are compared by vitamin K status of children (PIVKA-II > or ≤2 μg/L) in Table 1. There were no significant differences in most characteristics including gender and ethnicity between the two groups, except that children with VKD were slightly younger (p = 0.001) and reported a higher prevalence of fever in the previous week (p = 0.010) than children with vitamin K sufficiency. For lipid profiles, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), total cholesterol, and triglyceride concentrations were significantly higher in children with VKD (all p < 0.01); high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol did not differ by groups (p = 0.588). Prevalence of elevated concentrations of inflammation biomarkers such as C-reactive protein and α-1-acid glycoprotein were not different by groups.

Table 1.

Demographic, Anthropometric, Household, Dietary, and Health Characteristics of Nepalese Children by Vitamin K Statusa,b

| Child characteristics | Deficient (n = 100) | Sufficient (n = 400) | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Male, % | 50.0 | 49.8 | 1.000 |

| Age, years | 7.3 (0.5) | 7.5 (0.4) | 0.001 |

| Anthropometric measurements | |||

| Weight, kg | 18.3 (3.6) | 18.3 (2.3) | 0.912 |

| Height, cm | 113.8 (7.5) | 114.2 (5.5) | 0.640 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 14.1 (1.5) | 14.0 (1.0) | 0.498 |

| MUAC, cm | 15.4 (1.5) | 15.5 (1.1) | 0.768 |

| Undernutritiond % | |||

| Stunting (HAZ< −2) | 37.0 | 39.5 | 0.731 |

| Underweight (WAZ< −2) | 44.0 | 49.5 | 0.383 |

| Low BMI (BMIZ< −2) | 15.0 | 16.8 | 0.786 |

| Education% | |||

| Ever sent to school | 62.0 | 68.0 | 0.462 |

| Literacy | 18.0 | 17.3 | 0.977 |

| Ethnicity of household % | 0.791 | ||

| Pahadi | 30.0 | 31.3 | |

| Madheshi | 70.0 | 68.7 | |

| Economic of household % | |||

| Electricity | 50.0 | 51.3 | 0.911 |

| Land ownership | 71.0 | 78.5 | 0.144 |

| Diet, any intake in the past week % | |||

| Milk | 70.0 | 68.3 | 0.828 |

| Chicken | 20.0 | 19.8 | 1.000 |

| Fish | 20.0 | 22.0 | 0.765 |

| Other meat | 31.0 | 32.5 | 0.867 |

| Eggs | 14.0 | 18.8 | 0.335 |

| Dark green leafy vegetable | 74.0 | 72.0 | 0.783 |

| Morbidity, any symptom reported in the past week % | |||

| Poor appetite | 12.0 | 12.3 | 1.000 |

| Fever | 15.0 | 6.5 | 0.010 |

| Diarrhea | 2.0 | 3.5 | 0.657 |

| Any symptome | 24.0 | 24.3 | 1.000 |

| Lipid profilesf | |||

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 0.71 (0.57, 0.88) | 0.73 (0.60, 0.88) | 0.588 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.97 (1.79, 2.20) | 1.84 (1.58, 2.10) | 0.008 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 3.29 (2.94, 3.50) | 3.10 (2.80, 3.37) | 0.007 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.13 (0.88, 1.58) | 1.02 (0.78, 1.31) | 0.006 |

| Infection/inflammation, % | |||

| CRP >5 mg/L | 6.0 | 6.0 | 1.000 |

| AGP >1 g/L | 35.0 | 28.5 | 0.251 |

AGP, α-1-acid glycoprotein; BMI, body mass index; BMIZ, body mass index z score; CRP, C-reactive protein; HAZ, height-for-age z score; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PIVKA-II, protein induced vitamin K absence-II; WAZ, weight-for-age z score.

Children were divided into vitamin K deficient (PIVKA-II >2 μg/L) and sufficient (PIVKA-II ≤2 μg/L) groups.

Data are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated.

P value for group difference using t-test for continuous variables with normal distributions, Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables with skewed distributions, and chi-square test for categorical variables.

Anthropometric Z-scores were calculated based on the WHO reference for children 5–19 years of age.

Any symptom was defined as any symptom of poor appetite, vomiting, high fever, diarrhea, blood or white mucus in stool, productive cough, rapid breathing, blood in sputum, or painful urination in the past week.

Data are missing for HDL (n = 39), LDL (n = 176), total cholesterol (n = 149), and triglyceride (n = 28).

Among 978 plasma proteins identified and quantified in >10% of children (i.e. n > 50 children), five proteins were significantly associated with plasma concentration of PIVKA-II with at q < 0.10 (Table 2). Prothrombin or coagulation factor-II (F2) was most strongly associated with PIVKA-II, with a 137.5% increase in PIVKA-II concentration per 100% increase in relative abundance of F2. We also identified and quantified all seven hepatic pro- (coagulant factor II,VII, IX, and X) and anti-coagulation (protein C, S, and Z) VKDPs, but none were associated with PIVKA-II. Hemoglobin delta unit (HBD) was positively associated with PIVKA-II concentration with an 11.7% increase in PIVKA-II per 100% increase in relative abundance of HBD.

Table 2.

Plasma Proteins Associated with Plasma PIVKA-II in Nepalese Children 6–8 Years of Age (q < 0.10)

| Protein (Gene symbol)a | Accession | nb | Percent changec | Pd | qe | R2,f | Molecular/Biological function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prothrombin or coagulation factor II (F2) | 4503635 | 474 | 137.5 (50.1, 275.8) | 0.0002 | 0.0556 | 0.29 | Blood coagulation |

| Cadherin 5, type 2 (vascular endothelium) (CDH5) | 166362713 | 474 | −39.8 (−54.6, −20.1) | 0.0004 | 0.0649 | 0.29 | Control intercellular junctions |

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, alpha 2/delta1 (CACNA2D1) | 54112390 | 200 | −46.0 (−61.7, −23.8) | 0.0005 | 0.0649 | 0.30 | Mediate Ca2+ influx |

| Gelsolin (GSN) | 4504165 | 467 | −38.6 (−53.8, −18.6) | 0.0007 | 0.0895 | 0.30 | Regulate and severe actin filaments |

| Hemoglobin, delta (HBD) | 4504351 | 211 | 11.7 (4.7, 19.1) | 0.0008 | 0.0921 | 0.27 | Transport O2 |

Ca, calcium; O2, oxygen; PIVKA-II, protein induced vitamin K absence-II.

Putative prostaglandin E synthase 3-like (PTGES3; Protein GI accession number: 217416407) was also detected in 67 subjects (R2 = 0.36, p < 1 × 10−5, q < 0.01).

Maximum number of observation was 474 (n = 26 zero values were dropped due to log2 transformation of plasma PIVKA-II).

Percent change in PIVKA-II concentration with doubling (100% increase) of relative abundance of protein.

P value for hypothesis testing of a null association between PIVKA-II concentration and relative abundance of protein using a linear mixed model.

Multiple hypothesis testing was corrected using false discovery rate.

Variance in PIVKA-II concentration explained by protein.

For negative correlates, a 40%–45% decrease in PIVKA-II was associated with a 100% increase in relative abundance of vascular endothelium cadherin 5 (CDH5), voltage-dependent calcium channel α2δ1 (CACNA2D1), and gelsolin (GSN). Individually, these proteins each explained about 30% of variability in PIVKA-II concentration in plasma. Another fifteen proteins were positively and negatively associated with PIVKA-II when a relaxed discovery threshold (q < 0.20) was applied, including α-1-B glycoprotein (A1BG), another hemoglobin subunit α1 (HBA1), endogenous antioxidative enzymes (catalase [CAT] and peroxiredoxin 2 [PRDX2]), carbonic anhydrase 2 (CA2), and cytoplasm/intracellular organelle proteins (Supplementary Table S2).

Seven proteins were differentially abundant by vitamin K status of children at q < 0.10 (Table 3). Endoplasmic reticulum protein 44, F2, inhibin beta E, zinc finger protein 645, heparin cofactor, and A1BG were approximately 4% ∼30% more abundant and CDH5 was 6% less abundant in the plasma of children with elevated PIVKA-II (>2 μg/L) relative to children with normal PIVKA-II concentration (≤2 μg/L). Another five proteins were differentially abundant by vitamin K status under a relaxed discovery threshold of q < 0.20, summarized in Supplementary Table S3.

Table 3.

Differentially Abundant Plasma Proteins Between Children with Vitamin K Deficiency and Sufficiency (q < 0.10)a

| Protein (Gene symbol) | Accession | nb | Percent differencec | Pd | qe | Molecular/Biological function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoplasmic reticulum protein 44 (ERP44) | 52487191 | 97 | 28.0 (14.2, 43.5) | 2.16 × 10−5 | 0.0228 | Control oxidative protein folding |

| Cadherin 5, type 2 (vascular endothelium) (CDH5) | 166362713 | 500 | −6.2 (−9.0, −3.4) | 2.86 × 10−5 | 0.0228 | Control intercellular junctions |

| Coagulation factor II (F2) | 4503635 | 500 | 3.6 (1.7, 5.5) | 0.0002 | 0.0612 | Blood coagulation |

| Inhibin, beta E (INHBE) | 13899338 | 97 | 30.4 (13.4, 50.0) | 0.0002 | 0.0612 | Regulate pituitary reproductive hormone secretion |

| Zinc finger protein 645 (ZNF645) | 22749189 | 388 | 10.4 (4.7,16.4) | 0.0003 | 0.0671 | Testis-specific E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| Heparin cofactor (SERPIND1) | 73858566 | 500 | 5.6 (2.5,8.8) | 0.0003 | 0.0671 | Thrombin inhibitor |

| Alpha-1-B glycoprotein (A1BG) | 21071030 | 500 | 3.6 (1.6, 5.6) | 0.0004 | 0.0758 | Unknown |

PIVKA-II, protein induced vitamin K absence-II.

Vitamin K deficiency and sufficiency were defined as PIVKA-II concentration > and ≤2 μg/L, respectively.

Maximum number of observation was 500.

Percent difference in protein abundance in children with vitamin K deficiency relative to children with vitamin K sufficiency.

P value for hypothesis testing of no difference in relative protein abundance between two groups.

Multiple hypothesis testing was corrected using false discovery rate.

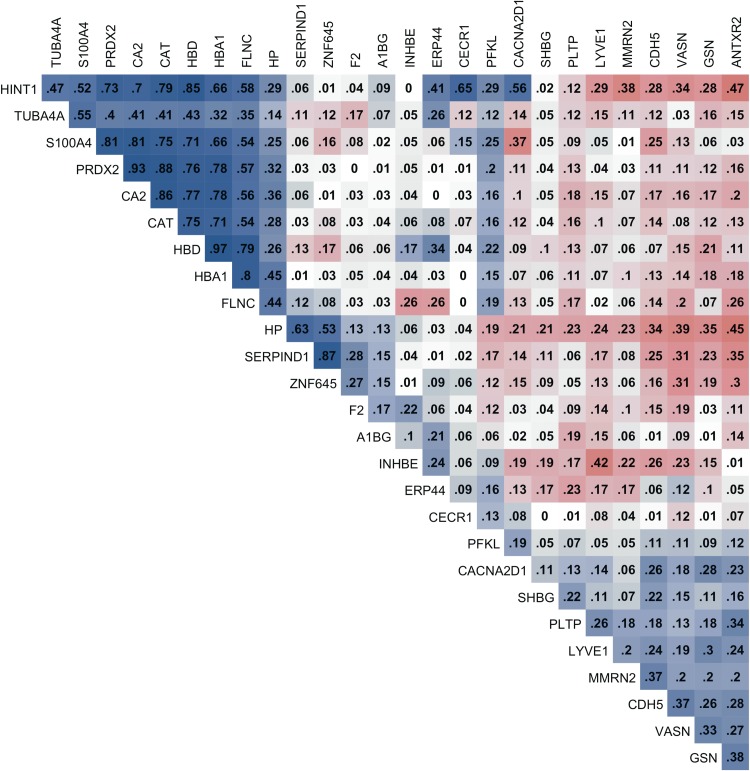

The correlation matrix of proteins associated with PIVKA-II or VKD (PIVKA-II >2 μg/L) showed that there are prominent, strong positive correlations among hemoglobin subunits and endogenous enzymes such as HBD, HBA1, CAT, CA2, and PRDX2 (all correlation coefficients >0.7) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Correlation matrix of relative abundance of plasma proteins associated with vitamin K status. Plasma proteins were associated with plasma protein induced vitamin K absence-II (PIVKA-II) concentration or differentially abundant by vitamin K status (PIVKA-II> or ≤2 μg/L), passing a relaxed discovery threshold, q < 0.20 (n = 27). Blue and red colors depict positive and negative correlation coefficients, respectively, and darker colors represent stronger correlation. Correlation coefficients less than ±0.01 were denoted as 0.

Discussion

Vitamin K status in children has not been frequently discussed as a public health issue except regarding its role in bone health and prevention of infant bleeding disorders. This study explored the plasma proteome in children living in rural Nepal in association with subclinical VKD, assessed by plasma concentration of PIVKA-II, an indicator of hepatic vitamin K depletion. Because our measurement of VK status was indirect, and because VK has no known carrier proteins, we did not expect to find a strong VK proteome, unlike the case for other nutrients we have explored (Cole et al., 2013; Schulze et al., 2015; West et al., 2015).

Nonetheless, five proteins moderately predicted plasma concentration of PIVKA-II at a threshold that limited the chance of a false positive to below 10% (q < 0.10). One was a hepatic blood coagulation protein, validating the proteomics approach, while others were extrahepatic in origin, including erythrocytes, suggesting there may be a spectrum of potential biological responses to subclinical vitamin K deficiency.

Few population estimates of vitamin K status exist in low-income countries. In this rural setting of Nepal, 20% of early school-aged children were mildly vitamin K-deficient (PIVKA-II >2 μg/L), a prevalence that is comparable in magnitude to other co-existing micronutrient deficiencies in this population (Schulze et al., 2014), but exhibiting a far narrower and lower range of abnormal PIVKA-II values (i.e., 99% of PIVKA-II values ranged from 0 to 4 μg/L) than observed in children with hepato-billiary or inflammatory bowel diseases (Dougherty et al., 2010; Mager et al., 2006; Nowak et al., 2014; Strople et al., 2009). This implies that changes in relative abundance of plasma proteins corresponding to PIVKA-II concentration may be reflecting diverse homeostatic responses to subclinical vitamin K status in a generally undernourished pediatric population.

In this study, a positive association was observed between PIVKA-II, measured by an immunoassay specific for abnormal prothrombin, and coagulation cofactor-II (or prothrombin, F2), measured by mass spectrometry. The MS-based proteomic abundance data of F2 probably reflects total prothrombin, including heterogeneous forms of under-carboxylated prothrombin, as well as completely carboxylated prothrombin. As far as we know, no comparable studies have examined the relationship between PIVKA-II and total prothrombin in healthy children.

Based on experimental or clinical studies, warfarin (vitamin K antagonist) or prenatal anticonvulsants can induce VKD, determined by an increased PIVKA-II, but only slightly decrease total prothrombin (Bach et al., 1996; Howe et al., 1999; Motohara et al., 1985). It is likely that the mild VKD in children observed in this study resulted in slightly increased abnormal forms of prothrombin rather than altering hepatic synthesis and release of normal prothrombin. This is supported by the result of proteomics data showing that MS-based total prothrombin (F2) was only 3.6% more abundant in children with VKD relative to children with vitamin K sufficiency (Table 3). Notably, none of the detected hepatic pro- and anti-coagulating VKDPs, other than F2, were associated with PIVKA-II, suggesting that suboptimal VKD status did not affect abundance of other hepatic-derived vitamin K-dependent clotting factors possibly due to their higher affinities with ϒ-glutamyl carboxylase than prothrombin (Stanley et al., 1999).

Proteins of extrahepatic origins were negatively associated with PIVKA-II. Vascular endothelial cadherin 5 (CDH5) is a calcium-dependent cell adhesion protein, controlling the vascular integrity or permeability of intercellular tight junctions in blood vessels (Dejana et al., 2009; Vestweber, 2008). Voltage-dependent calcium channel α2/δ1 (CACNA2D1) is a subunit of a transmembrane calcium channel that mediates intracellular Ca2+ influx and initiates diverse physiological events, including muscular contraction, excitation of neurons, and release of hormones or neurotransmitters (Hofmann et al., 1999). This subunit is expressed in excitable cells of diverse tissues including brain, heart, and skeletal muscle (Klugbauer et al., 2003).

Gelsolin (GSN) is a Ca2+-dependent protein that regulates actin filament assembly or disassembly in cytoplasm and efficiently severs actin present in plasma (Furukawa et al., 1997; Lind et al., 1986). A low level of GSN is associated with pathological conditions such as hemolysis, endothelial injury, apoptosis, and inflammation with poor clinical outcomes (Li et al., 2012). Mechanisms are not clear by which abundance of these calcium dependent proteins inversely associate with PIVKA-II. It can be postulated that they may involve changes in local tissue environments induced by disturbed functions of extrahepatic VKDPs. For example, some VKDPs, such as osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein (MGP), localize in bone, cartilage, vessels and smooth muscle where they regulate mineralization and calcification of extracellular matrix (Ferland, 2012a; Krueger et al., 2009; Shea and Holden, 2012; Theuwissen et al., 2012). Still, more studies are warranted to examine these relationships.

Unexpectedly, proteins primarily of red blood cell origin (hemoglobin subunits alpha1, delta, and beta) were positively associated with PIVKA-II (all q < 0.22). Hemoglobin is the most abundant protein in erythrocytes and is released into plasma when red cells undergo intravascular hemolysis (Schaer et al., 2013). Cell-free plasma hemoglobin is cytotoxic, inducing endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress (Rother et al., 2005). Endogenous erythrocyte antioxidative enzymes, peroxiredoxin 2 (PRX2) and catalase (CAT), and carbonic anhydrase II (CA2), an enzyme that catabolizes carbon dioxide and adjusts blood pH, were also positively associated with PIVKA-II (Backman, 1981; Han et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2005; Kuo et al., 2005; Lehenkari et al., 1998). Strong correlations among hemoglobin subunits and endogenous enzymes (all r > 0.7 in Fig. 1) suggest that these proteins may be closely co-regulated in a common biological process.

Limited studies have examined the link between vitamin K status and the stability of red blood cells. A study reported that long-term warfarin (vitamin K antagonist) intake induced cytokine expression in peripheral granulocytes and erythrocyte CAT activity in rats, suggesting VKD induced inflammation in immune cells and oxidative-stressed erythrocytes (Belij et al., 2012). Although we did not find evidence of systemic inflammation in our study (Table 1), moderate positive associations between PIVKA-II and PRX2, CAT and CA2 suggest that VKD may be indirectly related to oxidative stress and hemolysis in the intravascular compartment.

Risk factors of elevated PIVKA-II concentration in this study population are unclear. There were no apparent differences in intakes of dark green leafy vegetables, a major source of vitamin K, or other food groups between vitamin K sufficient and deficient children. Interestingly, children with elevated PIVKA-II showed higher concentrations of triglyceride and LDL/total cholesterol than children with a normal PIVKA-II, suggesting lipid metabolism could be associated with elevated PIVKA-II. After intestinal uptake, vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) is mainly transported by triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL) to the liver and extrahepatic tissues (Sadowski et al., 1989; Shearer et al., 1974; Yan et al., 2005).

Some studies suggest that different genotypes of apolipoprotein E, a ligand for TRL or LDL receptors, is responsible for the extent of cellular uptake of lipoproteins, ultimately influencing hepatic or extrahepatic vitamin K status (Kohlmeier et al., 1995; Weintraub et al., 1987). While mechanisms remain unclear, variations in lipid/cholesterol metabolism may increase risk of subclinical VKD in children (Booth and Rajabi, 2008).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to take a systematic -omics approach to explore biological responses to vitamin K status in a free-living population of children. We previously reported plasma proteins associated with some micronutrients and inflammation biomarkers (Cole et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2015; Schulze et al., 2015; West et al., 2015), but distinct proteins associated with PIVKA-II from the plasma proteins of other micronutrients and health indicators suggest that plasma proteomics can identify proteins or biological processes specific to vitamin K status.

Quantitative multiplex proteomics enabled us to profile approximately 980 plasma proteins and generate hypotheses on molecular roles of vitamin K. Within a mildly elevated, narrow range of PIVKA-II, our mass spectrometric approach with large sample size was able to detect subtle, but potentially physiologically significant differences in plasma protein abundance. Among the limitations were the cross-sectional design and sole reliance on plasma PIVKA-II concentration, which is not specific to vitamin K status, and can vary with hepatic or other pathological conditions (Liebman et al., 1984). Relatively high variability in the PIVKA-II assay may lead to misclassification of children's vitamin K status and limit our ability to identify some plasma proteins differentially abundant by vitamin K status.

We were also unable to detect extrahepatic VKDPs, such as osteocalcin and MGP, which are sensitive markers of suboptimal vitamin K status (Booth et al., 2003; Schurgers et al., 2007). Based on the triage theory by McCann and Ames, extrahepatic VKDPs are more likely to be vitamin K-depleted prior to alterations in hepatic VKDPs because dysfunction in blood coagulation can be fatal (McCann and Ames, 2009). It is possible that extrahepatic VKDPs are low in abundance and were out of the detectable range of mass spectrometry.

Conclusions

This study revealed that plasma proteomics can identify proteins revealing known and novel biological variation to suboptimal vitamin K status in healthy children. Because vitamin K deficiency likely co-exists with lipid metabolic conditions and have public health consequence, there is an increased need to assess and monitor vitamin K status in populations. Identified protein biomarkers in this study may improve understanding of potential health risks of childhood vitamin K deficiency, especially in undernourished populations.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- A1BG

α-1-B glycoprotein

- CA2

carbonic anhydrase 2

- CACNA2D1

voltage-dependent calcium channel alpha/delta1

- CAT

catalase

- CDH5

vascular endothelium cadherin 5

- F2

prothrombin or coagulation factor II

- FDR

false discovery rate

- Gla

ϒ-carboxyglutamate

- Glu

glutamic acid

- GSN

gelsolin

- HBA1

hemoglobin subunit A1

- HBD

hemoglobin delta unit

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- iTRAQ

isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LME

linear mixed effects models

- MGP

matrix Gla protein

- MS

mass spectrometry

- PIVKA-II

protein induced by vitamin K absence-II

- PRDX2

peroxiredoxin 2

- TRL

triglyceride-rich lipoproteins

- VK

vitamin K

- VKD

vitamin K deficiency

- VKDPs

vitamin K dependent proteins

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA, U.S.A. through Grants OPP5241, “Assessment of Micronutrient Status by Nutriproteomics” (Senior Program Offcer: Yiwu He) for laboratory work and GH614 “Global Control of Micronutrient Deficiency” (Senior Program Officer: Ellen Piwoz) for field work. The original Nepal Nutrition Intervention Project Sarlahi trial was also supported through the Micronutrients for Health Cooperative Agreement (HRN-A-00-97-00015-00) between Johns Hopkins University and the Office of Health, Infectious Diseases and Nutrition, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Washington D.C. with additional support from the Sight and Life Global Nutrition Research Institute, Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.

We thank the Johns Hopkins Nutriproteomics Research Team, in addition to co-authors, including Margia Arguello, Raghothama Chaerkady, Hongie Cui, Lauren R. DeVine, Jaime Johnson, Robert O'Meally, Subarna K. Khatry, Ashika Nanayakkara-Bind, Hee-Sool Rho, and Fredrick Van Dyke. We thank Ingo Ruczinski for his proteomics modeling and analytic guidance and C. Conover Talbot, Jr. for assistance with the HUGO gene annotation. We acknowledge the significant contributions of all local members of the Nepal Nutrition Intervention Project-Sarlahi and study subjects and their families in the District of Sarlahi, Nepal.

Author contributions: KPW, RNC, KJS, JDY, JG, and PC designed research. RNC and KJS supervised laboratory work. LSFW managed dataset. SEL analyzed data. KPW, LSFW, and PC conducted the original field study. SEL drafted the manuscript, and had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Anderson NL, and Anderson NG. (2002). The human plasma proteome: History, character, and diagnostic prospects. Mol Cell Proteomics 1, 845–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach AU, Anderson SA, Foley AL, Williams EC, and Suttie JW. (1996). Assessment of vitamin K status in human subjects administered “minidose” warfarin. Am J Clin Nutr 64, 894–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman L. (1981). Binding of human carbonic anhydrase to human hemoglobin. Eur J Biochem 120, 257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belij S, Miljkovic D, Popov A, et al. (2012). Effects of subacute oral warfarin administration on peripheral blood granulocytes in rats. Food Chem Toxicol 50, 1499–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth SL. (2009). Roles for vitamin K beyond coagulation. Annu Rev Nutr 29, 89–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth SL, Martini L, Peterson JW, Saltzman E, Dallal GE, and Wood RJ. (2003). Dietary phylloquinone depletion and repletion in older women. J Nutr 133, 2565–2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth SL, and Rajabi AA. (2008). Vitamin K: Determinants of Vitamin K Status in Humans. Elsevier Science, San Diego, CA, pp. 1–16 [Google Scholar]

- Cashman KD. (2005). Vitamin K status may be an important determinant of childhood bone health. Nutr Rev 63, 284–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian P, Khatry SK, Katz J, et al. (2003). Effects of alternative maternal micronutrient supplements on low birth weight in rural Nepal: Double blind randomised community trial. BMJ 326, 571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RN, Ruczinski I, Schulze K, et al. (2013). The plasma proteome identifies expected and novel proteins correlated with micronutrient status in undernourished Nepalese children. J Nutr 143, 1540–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejana E, Tournier-Lasserve E, and Weinstein BM. (2009). The control of vascular integrity by endothelial cell junctions: Molecular basis and pathological implications. Dev Cell 16, 209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dituri F, Buonocore G, Pietravalle A, et al. (2012). PIVKA-II plasma levels as markers of subclinical vitamin K deficiency in term infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 25, 1660–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty KA, Schall JI, and Stallings VA. (2010). Suboptimal vitamin K status despite supplementation in children and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Am J Clin Nutr 92, 660–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnouf MP, and Prowse CV. (1977). The gamma-carboxy glutamic acid content of human and bovine prothrombin following warfarin treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta 490, 471–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO, 2002. Chapter 10. Vitamin K. Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements. FAO/WHO, Rome, pp. 133–150 [Google Scholar]

- Ferland G. (2012a). Present Knowledge in Nutrition: Vitamin K, 10th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, pp. 230–247 [Google Scholar]

- Ferland G. (2012b). Vitamin K and the nervous system: An overview of its actions. Adv Nutr 3, 204–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald WT, Levy RI, and Fredrickson DS. (1972). Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 18, 499–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Fu W, Li Y, Witke W, Kwiatkowski DJ, and Mattson MP. (1997). The actin-severing protein gelsolin modulates calcium channel and NMDA receptor activities and vulnerability to excitotoxicity in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 17, 8178–8186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YH, Kim SU, Kwon TH, et al. (2012). Peroxiredoxin II is essential for preventing hemolytic anemia from oxidative stress through maintaining hemoglobin stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 426, 427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemker HC, Muller AD, and Loeliger EA. (1970). Two types of prothrombin in vitamin K deficiency. Thromb Diath Haemorrh 23, 633–637 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbrich SM, Cole RN, West KP Jr., et al. (2013). Statistical inference from multiple iTRAQ experiments without using common reference standards. J Proteome Res 12, 594–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Lacinova L, and Klugbauer N. (1999). Voltage-dependent calcium channels: From structure to function. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 139, 33–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe AM, Oakes DJ, Woodman PD, and Webster WS. (1999). Prothrombin and PIVKA-II levels in cord blood from newborn exposed to anticonvulsants during pregnancy. Epilepsia 40, 980–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Goyette G, Jr., Ravindranath Y, and Ho YS. (2005). Hemoglobin autoxidation and regulation of endogenous H2O2 levels in erythrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 39, 1407–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkwarf HJ, Khoury JC, Bean J, and Elliot JG. (2004). Vitamin K, bone turnover, and bone mass in girls. Am J Clin Nutr 80, 1075–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klugbauer N, Marais E, and Hofmann F. (2003). Calcium channel alpha2delta subunits: differential expression, function, and drug binding. J Bioenerg Biomembr 35, 639–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeier M, Saupe J, Drossel HJ, and Shearer MJ. (1995). Variation of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) concentrations in hemodialysis patients. Thromb Haemost 74, 1252–1254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger T, Westenfeld R, Schurgers L, and Brandenburg V. (2009). Coagulation meets calcification: The vitamin K system. Int J Artif Organs 32, 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH, Yang SF, Hsieh YS, Tsai CS, Hwang WL, and Chu SC. (2005). Differential expression of carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes in various types of anemia. Clin Chim Acta 351, 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, West KP, Jr., Cole RN, et al. (2013). Plasma proteome biomarkers of inflammation in school aged children in Nepal. PLoS One 10, e0144279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehenkari P, Hentunen TA, Laitala-Leinonen T, Tuukkanen J, and Vaananen HK. (1998). Carbonic anhydrase II plays a major role in osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption by effecting the steady state intracellular pH and Ca2+. Exp Cell Res 242, 128–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GH, Arora PD, Chen Y, McCulloch CA, and Liu P. (2012). Multifunctional roles of gelsolin in health and diseases. Med Res Rev 32, 999–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman HA, Furie BC, Tong MJ, et al. (1984). Des-gamma-carboxy (abnormal) prothrombin as a serum marker of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 310, 1427–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind SE, Smith DB, Janmey PA, and Stossel TP. (1986). Role of plasma gelsolin and the vitamin D-binding protein in clearing actin from the circulation. J Clin Invest 78, 736–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager DR, McGee PL, Furuya KN, and Roberts EA. (2006). Prevalence of vitamin K deficiency in children with mild to moderate chronic liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 42, 71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann JC, and Ames BN. (2009). Vitamin K, an example of triage theory: Is micronutrient inadequacy linked to diseases of aging? Am J Clin Nutr 90, 889–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motohara K, Kuroki Y, Kan H, Endo F, and Matsuda I. (1985). Detection of vitamin K deficiency by use of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for circulating abnormal prothrombin. Pediatr Res 19, 354–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak JK, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U, Landowski P, et al. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of vitamin K deficiency in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Rep 4, 4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor E, Molgaard C, Michaelsen KF, Jakobsen J, Lamberg-Allardt CJ, and Cashman KD. (2007). Serum percentage undercarboxylated osteocalcin, a sensitive measure of vitamin K status, and its relationship to bone health indices in Danish girls. Br J Nutr 97, 661–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson RE. (1984). The function and metabolism of vitamin K. Annu Rev Nutr 4, 281–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presnell SR, and Stafford DW. (2002). The vitamin K-dependent carboxylase. Thromb Haemost 87, 937–946 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team, 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- Robinson GK. (1991). That BLUP is a good thing: The estimation of random effects. Stat Sci 6, 15–32 [Google Scholar]

- Rother RP, Bell L, Hillmen P, and Gladwin MT. (2005). The clinical sequelae of intravascular hemolysis and extracellular plasma hemoglobin: A novel mechanism of human disease. JAMA 293, 1653–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski JA, Hood SJ, Dallal GE, and Garry PJ. (1989). Phylloquinone in plasma from elderly and young adults: Factors influencing its concentration. Am J Clin Nutr 50, 100–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaer DJ, Buehler PW, Alayash AI, Belcher JD, and Vercellotti GM. (2013). Hemolysis and free hemoglobin revisited: Exploring hemoglobin and hemin scavengers as a novel class of therapeutic proteins. Blood 121, 1276–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze KJ, Christian P, Wu LS, et al. (2014). Micronutrient deficiencies are common in 6- to 8-year-old children of rural Nepal, with prevalence estimates modestly affected by inflammation. J Nutr 144, 979–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze KJ, Cole RN, Chaerkady R, et al. (2015). Plasma selenium protein P isoform 1 (SEPP1): A predictor of selenium status in Nepalese children detected by plasma proteomics. Int J Vitam Nutr Res (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurgers LJ, Spronk HM, Skepper JN, et al. (2007). Post-translational modifications regulate matrix Gla protein function: Importance for inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J Thromb Haemost 5, 2503–2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea MK, and Holden RM. (2012). Vitamin K status and vascular calcification: Evidence from observational and clinical studies. Adv Nutr 3, 158–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer MJ. (2009). Vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) in early infancy. Blood Rev 23, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer MJ, McBurney A, and Barkhan P. (1974). Studies on the absorption and metabolism of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in man. Vitam Horm 32, 513–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley TB, Jin DY, Lin PJ, and Stafford DW. (1999). The propeptides of the vitamin K-dependent proteins possess different affinities for the vitamin K-dependent carboxylase. J Biol Chem 274, 16940–16944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenflo J, Fernlund P, Egan W, and Roepstorff P. (1974). Vitamin K dependent modifications of glutamic acid residues in prothrombin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71, 2730–2733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CP, Christian P, Leclerq SC, West KP, Jr., and Khatry SK. (2009a). Antenatal supplementation with folic acid + iron + zinc improves linear growth and reduces peripheral adiposity in school-age children in rural Nepal. Am J Clin Nutr 90, 132–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CP, Christian P, Schulze KJ, Leclerq SC, West KP, Jr., and Khatry SK. (2009b). Antenatal micronutrient supplementation reduces metabolic syndrome in 6- to 8-year-old children in rural Nepal. J Nutr 139, 1575–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroey JD. (2002). A direct approach to false discovery rates. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat 64, 479–498 [Google Scholar]

- Strople J, Lovell G, and Heubi J. (2009). Prevalence of subclinical vitamin K deficiency in cholestatic liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 49, 78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttie JW. (1980). Mechanism of action of vitamin K: Synthesis of gamma-carboxyglutamic acid. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 8, 191–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttie JW. (1992). Vitamin K and human nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc 92, 585–590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttie JW. (2009). Vitamin K in health and disease. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- Theuwissen E, Smit E, and Vermeer C. (2012). The role of vitamin K in soft-tissue calcification. Adv Nutr 3, 166–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestweber D. (2008). VE-cadherin: The major endothelial adhesion molecule controlling cellular junctions and blood vessel formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28, 223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub MS, Eisenberg S, and Breslow JL. (1987). Dietary fat clearance in normal subjects is regulated by genetic variation in apolipoprotein E. J Clin Invest 80, 1571–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West KP, Jr., Cole RN, Shrestha S, et al. (2015). A plasma alpha-tocopherome can be identified from proteins associated with Vitamin E status in school-aged children of Nepal. J Nutr 145, 2646–2656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Zhou B, Nigdikar S, Wang X, Bennett J, and Prentice A. (2005). Effect of apolipoprotein E genotype on vitamin K status in healthy older adults from China and the UK. Br J Nutr 94, 956–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerfas AJ. (1975). The insertion tape: A new circumference tape for use in nutritional assessment. Am J Clin Nutr 28, 782–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.