Abstract

A central resistance mechanism in solid tumors is the maintenance of epithelial junctions between malignant cells that prevent drug penetration into the tumor. Human adenoviruses (Ads) have evolved mechanisms to breach epithelial barriers. For example, during Ad serotype 3 (Ad3) infection of epithelial tumor cells, massive amounts of subviral penton-dodecahedral particles (PtDd) are produced and released from infected cells to trigger the transient opening of epithelial junctions, thus facilitating lateral virus spread. We show here that an Ad3 mutant that is disabled for PtDd production is significantly less effective in killing of epithelial human xenograft tumors than the wild-type Ad3 virus. Intratumoral spread and therapeutic effect of the Ad3 mutant was enhanced by co-administration of a small recombinant protein (JO; produced in Escherichia coli) that incorporated the minimal junction opening domains of PtDd. We then demonstrated that co-administration of JO with replication-competent Ads that do not produce PtDd (Ad5, Ad35) resulted in greater attenuation of tumor growth than virus injection alone. Furthermore, we genetically modified a conditionally replicating Ad5-based oncolytic Ad (Ad5Δ24) to express a secreted form of JO upon replication in tumor cells. The JO-expressing virus had a significantly greater antitumor effect than the unmodified AdΔ24 version. Our findings indicate that epithelial junctions limit the efficacy of oncolytic Ads and that this problem can be address by co-injection or expression of JO. JO has also the potential for improving cancer therapy with other types of oncolytic viruses.

Introduction

A series of DNA and RNA viruses have been used in wild-type or modified forms for oncolytic therapy. This includes vesicular stomatitis virus, Maraba virus, poliovirus, reovirus, measles virus, Newcastle disease virus (NDV), coxsackievirus A21, parvovirus, vaccinia virus, herpes simplex virus type 1, and adenovirus (Ad).1–3 The theoretical premise for oncolytic virotherapy is that, after systemic or local administration, viruses preferentially infect and replicate in tumor cells, resulting in cell lysis and release of de novo-produced virions. Progeny virions will then infect neighboring tumor cells and thus spread throughout the tumor. Among the obstacles to efficient oncolytic virotherapy are antivirus immune responses, inefficient tumor cell infection, and physical barriers to intratumoral viral spread. The latter is the focus of our study.

Greater than 80% of all cancer cases are carcinomas, formed by the malignant transformation of epithelial cells. One of the key features of epithelial tumors is the presence of intercellular junctions, which link tumor cells to one another.4–7 Epithelial junctions act as barriers to the penetration of molecules with a molecular weight of >400 Da and therefore serve as a basic resistance mechanism that protects tumor cells from host antibody- or cell-mediated antitumor immune responses.8–10 Notably, for most carcinomas, progression to malignancy is accompanied by a loss of epithelial differentiation and a shift toward a mesenchymal phenotype through an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT).11 EMT increases migration and invasiveness and is often one of the prerequisites for metastasis. However, after metastasis, cells that have undergone EMT are thought to revert to a well-differentiated epithelial phenotype through mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), thereby regaining epithelial junctions.12,13 Epithelial junctions are therefore also a barrier for drugs in metastatic lesions.

Epithelial junctions in solid tumors also represent barriers to penetration of tumor therapy agents, including monoclonal antibodies and chemotherapy drugs.14–16 A series of studies demonstrated that, because of epithelial junctions, intravenously injected drugs penetrate only a few cell layers from the blood vessel into the tumor.7,17,18 This implies that more distant tumor cells are exposed to lower drug concentrations that are noncytotoxic. It is thought that this triggers the formation of cancer cells with stem cell features that later drive cancer recurrence.19–21

Here we postulate that epithelial junctions in solid tumors represent a barrier to the intratumoral spread of oncolytic viruses, specifically oncolytic Ads. Ads have a protein capsid with a diameter of ∼90–100 nm. The receptor-interacting domain in the Ad capsid is called the fiber. Most oncolytic Ads are based on species C serotype 5 (Ad5), which uses the coxsackie-Ad receptor (CAR) for infection. A number of Ad5-derived oncolytic viruses have been or are being tested in clinical trials.2,3 CG0070, a GM-CSF-expressing conditionally replicating oncolytic Ad5 virus, is currently tested in phase III in patients with invasive epithelial bladder cancer after intravesicular infusion with a detergent to breach epithelial barriers.22 Oncolytic Ad5 viruses containing RGD peptide ligands in their capsids to expand the cell tropism are used in glioma (DNX2401) and metastatic melanoma (ICOVIR-5) trials. ONCOS102 is an Ad5/3 capsid chimeric oncolytic virus armed with GM-CSF, which has been tested in patients with refractory solid tumors.2 For most of these viruses, conditional viral replication in tumor cells is achieved, in part, by the use of an E1A mutant with a 24 bp deletion in the pRb-binding domain (Ad5Δ24). Among these viruses is VCN-01, an Ad5Δ24 virus that expressed hyaluronidase to break down tumor stroma proteins and increase viral spread.23

Whereas Ad5 viruses use CAR for infection, we recently discovered that human species B Ad serotypes, including Ad3, 7, 11, and 14, infect cells through desmoglein 2 (DSG2).24–26 DSG2 is a calcium-binding transmembrane glycoprotein belonging to the cadherin protein family. In epithelial cells of the respiratory, gastro-intestinal, and urinary tracts, DSG2 is a component of the cell–cell adhesion structure.27 DSG2 is overexpressed in epithelial cancer.4,5,19

In general, during Ad infection, the penton base and fiber proteins are produced in excess and assemble in the cytosol to form fiber–penton base hetero-oligomers called pentons.28,29 In the case of DSG2-interacting Ads, specifically Ad3, Ad14, and Ad14P1, 12 pentons self-assemble into dodecamers (penton-dodecahedral particles [PtDd]) with a diameter of ∼30 nm that are released from infected cells early during infection before cell lysis.30,31 Recently, we demonstrated that the ability of Ad3 to produce PtDd is critically important for viral spread in epithelial tumors.31 Specifically, we showed that PtDd interaction with DSG2 triggers intracellular signaling that culminates in transient opening of epithelial junctions, thus facilitating later spread of de novo-produced Ad3 virions.24,32

To capitalize on the mechanism that DSG2-interacting Ads have evolved to breach epithelial barriers, we developed a small recombinant protein that encompasses the minimal structural domain of PtDd required for junction opening (JO).19,33–35 JO is a self-dimerizing recombinant protein derived from the Ad3 fiber protein.35 It can be easily produced in Escherichia coli and purified by affinity chromatography. In JO, the C-terminal fiber protein domain, the so-called fiber knob, is modified to increase its affinity to DSG2. JO binds with picomolar affinity to DSG2 and causes clustering of several DSG2 molecules, which in turn triggers intracellular signaling that culminates in junction opening. This mechanism involves the phosphorylation of MAP kinases triggering the activation of the matrix-metalloproteinase ADAM17. ADAM17 in turn cleaves the extracellular domain of DSG2 that links epithelial cells together. The shed DSG2 domain can be detected in cell culture supernatant and also in serum of mice with established human xenograft tumors after intravenous JO injection.32

We have shown in over 25 xenograft models that the intravenous injection of JO increased the efficacy of cancer therapies, including many different monoclonal antibodies and chemotherapy drugs, in a broad range of epithelial tumors.19,33 Intravenous injection of JO was safe and well-tolerated in toxicology studies carried out in human DSG2-transgenic mice and macaques.36 Notably, in normal epithelial tissues, which display a strict apical basal polarization, DSG2 is trapped in lateral junctions and not readily accessible to intravenously injected ligands. In contrast, in epithelial tumors this polarization is lost and DSG2 can be found on all membrane sides of tumor cells.34 JO therefore acts preferentially on junctions in tumors.

We plan to test JO in patients with progressive ovarian cancer in combination with PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) and have started clinical manufacturing and IND-enabling studies.36

Here we demonstrate that recombinant JO increases the antitumor effect of replication-competent Ads that do not use DSG2 as a primary receptor. Furthermore, we have armed a conditionally replicating oncolytic Ad with the gene of a secreted form of JO and demonstrated increased oncolytic activity of this vector.

Materials and Methods

Proteins

JO was produced in E. coli with an N-terminal 6-His tag, using the pQE30 expression vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and purified by Ni-NTA agarose chromatography as described elsewhere.37 JO preparations used in animals were depleted of bacterial endotoxin using Endotrap blue 1/1 columns (Hyglos GmbH, Bernried, Germany).

Cell lines

293 cells (Microbix, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and HeLa, HT29, and A549 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM L-glutamine (Glu), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (pen-strep). CHO cells were cultured as above with additional nonessential amino acids.

Adenoviruses

Propagation and purification of Ads were performed as described elsewhere.38 wt-Ad3GFP is a wild-type Ad3-based vector containing a CMV-GFP expression cassette inserted into the E3 region.24 mu-Ad3GFP is based on wt-Ad3GFP but contains D100R and R425E mutations in the penton base gene that disable the virus to produce PtDd.31 ColoAd1 is a chimeric Ad11/Ad3 virus.39 Ad3-hTERT-E1A is a fully serotype 3-based oncolytic Ad (provided by Akseli Hemminki, University of Helsinki, Finland).40

Construction of wt-Ad5GFP and wt-Ad35GFP

The E3 regions of wild-type Ad5 and Ad35 genomes were partially substituted with the GFP expression cassette. Notably, in Ad5, the E3 region is thought not to be essential for virus replication. For the construction of wt-Ad5GFP, wt-Ad5-containing plasmid pFG14041 was digested with BstZ17I to generate two fragments (14,783 and 23,238 bp), and the smaller fragment was self-ligated to generate plasmid pFG140BstZ17I. The GFP expression cassette containing the CMV promoter, GFP coding sequence, and the bGH poly A signal was amplified by PCR using template pWEA-Ad3GFP and primers 5′-GGCCCTCGAG TTGACATTGA TTATTGACTA GTTATTAATA G-3′ and 5′-GATGCTTTAT TATTTTTTTT TATTAGTTCA TAGAGCCCAC CGCATCC-3′.24,34 A 297 bp adapter fragment was amplified by PCR using pFG140 as the template with primers 5′-GGATGCGGTG GGCTCTATGA ACTAATAAAA AAAAATAATA AAGCATC-3′ and 5′-GGCCACCGGT TTCCGTGTCA TATGGATACA CGG-3′. The GFP expression frame was fused with the adapter by overlap extension PCR to generate a product of 1954 bp in length.42 The 1954 bp PCR product was digested with XhoI/AgeI and inserted into the corresponding sites of pFG140BstZ17I to generate pFG140BstZ17IG (15,516 bp). pFG140BstZ17IG was digested with BstZ17I, treated with CIP, and ligated with the 23,238 bp fragment to generate pFG140GFP plasmid (38,754 bp). Because pFG140 was an Ad5 genome-containing plasmid in which antibiotic-resistance gene and plasmid replication origin sequence were inserted into the XbaI site of the E1 region,41 pFG140GFP was digested with XbaI (2210 and 36,544 bp), and 36,544 bp fragment was recovered and self-ligated to restore the integrity of the E1 region. pFG140GFP/XbaI DNA was mixed with pcDNA3, which served as a stuffer DNA to meet the DNA mass requirement of gene transfection, and was used to transfect 293 cells to rescue GFP-carrying replication-competent Ad5 (wt-Ad5GFP). For the construction of wt-Ad35GFP, pGEM-Ad3543 (a generous gift from Dr. Hiroyuki Mizuguchi, Osaka University) was digested with EcoRV, and the 5754 and 32,003 bp fragments were recovered separately. Plasmid backbone (kanamycin-resistant gene and replication origin) was amplified by PCR using pSh41CMV as the template with primers of 5′-ccgggatatc cgatcccg agcggtatca gctc-3′ and 5′-CCGGGATATC AAACTGGA ACAACACTCA ACCCTATC-3′.44 The PCR product (2488 bp) was digested with EcoRV, treated with CIP, and ligated with the 5754 bp fragment to generate pKAd35EV (8228 bp). GFP expression frame was amplified by PCR using pWEA-Ad3GFP as the template with primers of 5′- GGCCGGTACC TTGACATTGA TTATTGACTA GTTATTAAT-3′ and 5′- GGCCACGCGT CATAGAGCCC ACCGCATCCC-3′.24,34 The GFP-containing fragment was digested with KpnI/MluI, and inserted into the corresponding sites of pKAd35EV to generate pKAd35GFP-EV (9118 bp). pKAd35GFP-EV was digested with EcoRV (2474 and 6644 bp), and the 6644 bp fragment was ligated with the 32,003 bp fragment to generate pGEM-Ad35GFP (38,647 bp). pGEM-Ad35GFP was digested with NotI/SbfI to release the virus genome (35,688 bp), which was used to transfect 293 cells to rescue GFP-carrying replication-competent Ad35 (wt-Ad35GFP).

Generation of Ad5Δ24-JO

The plasmid pF5-IRES-Luc contains the coding sequence for the Ad5 fiber followed by an IRES site, followed by a firefly luciferase gene. Here, the luciferase gene was replaced by a sequence encoding a His-tagged JO that is preceded by an Igκ leader. The F5-IRES-His-JO cassette was PCR-amplified using the primers E3-fwd (ACGACAGTAATACCACCGGACACCGC) and E4-rev (AGGTGGCAGGTTGAATACTAGGG). For recombineering, SW102 bacteria45 were transformed with the BAC BAdVK500-galK, containing the Ad5 genome with delta24 and deltaE3 modifications as well as a galK cassette encoding for both a galacto kinase and a ampicillin resistance (both kindly provided by Michael Behr and Dirk Nettelbeck, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany). Rescued bacteria containing the above BAC were then transformed with the F5-IRES-His-JO1 cassette and the heat-shock-inducible recombination machinery is activated to replace the galK cassette with F5-IRES-His-JO. Bacteria that successfully performed recombination and deleted the galK cassette were then selected on minimal agar plates containing deoxy-galactose (DOG). In case of unsuccessful recombination, the galacto kinase would metabolize DOG into a toxic end product. The resulting BAC BAdVK500-F5-IRES-His-JO was amplified and digested with PacI to release the viral genome. The viral genome was then transfected into low-passage 293 cells and after occurrence of CPE, the virus, Ad5-Δ24-ΔE3-F5-IRES-His-JO (Ad5Δ24-JO), was amplified and purified using cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation.

Viruses were amplified in 293 cells and purified by CsCl gradient ultracentrifugation. Viral particle (vp) concentrations were determined by spectrophotometric measurement of the optical density at 260 nm (OD260).

Animal studies

All experiments involving animals were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines set forth by the University of Washington. The University of Washington is an Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AALAC)–accredited research institution and all live animal work conducted at this university is in accordance with the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) Public Health Assurance (PHS) policy, USDA Animal Welfare Act and Regulations, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the University of Washington's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) policies. The studies were approved by the University of Washington IACUC (Protocol No. 3108-01). Immunodeficient NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/J (CB17) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed in specific-pathogen-free facilities. A549 and HT-29 xenograft tumors were established by subcutaneous injection of 2 × 106 cells. Ad (4 × 1010 vp/mouse) was injected either intratumorally or intravenously. JO (50 μg/mouse) was injected intratumorally or intravenously as indicated in the figure legends. Tumor volumes were measured as described previously.46 Animals were sacrificed and the experiment terminated when tumors reached a volume of 1000 mm3 or when tumors displayed ulceration.

For analysis of tumor cell suspensions, tumors were digested with collagenase/dispase as described earlier.47 GFP expression in tumor cell suspensions was analyzed by flow cytometry.

qPCR for viral genome copy numbers

Subcutaneous A549 xenograft tumors were implanted into CB17-SCID mice. Animals received intratumoral virus injections. Animals were sacrificed one and three days after the second injection, and the tumors were resected and snap-frozen. Genomic DNA of tumor samples was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's specifications. The presence of viral genomes in the gDNA samples (diluted 1:1000) was determined via quantitative PCR (qPCR) using the Ad hexon-specific primers Ad-hexon-fwd (GCCCCAGTGGTCATACATGCA) and Ad-hexon-rev (GCCACGGTGGGGTTTCTAAAC). Dilutions of Ad viral genomic DNA were used to generate a standard curve. Per virus and time point, three animals were analyzed.

JO ELISA

The ELISA consisted of a polyclonal rabbit antibody directed against the Ad3 fiber knob as capture antibody and a mouse monoclonal ant-Ad3 fiber knob antibody (clone 2-1) as detection antibody.48 The sensitivity of the ELISA was 0.5 ng/ml.

DSG2 ELISA

ELISA was performed using a goat polyclonal anti-DSG2 antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and the mouse monoclonal antibody 6D8 directed against ECD3 (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC). The detection limit of the DSG2 ELISA was 0.5 ng/ml.

JO Western blot

For JO detection, monoclonal antibody clone 1-2 was used as described previously.24

Serum transaminase levels

ALT and AST levels were measured by a kit from Biotron Diagnostics Inc. (Hermes, CA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of in vivo data was analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log-rank test (GraphPad Prism Version 4). Statistical significance of in vitro data was calculated by the two-sided Student's t-test (Microsoft Excel). p-Values >0.05 were considered not statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

An Ad3 mutant that is disabled for junction opening has a decreased antitumor efficacy

Previously, based on the 3D structure of Ad3 PtDd, we introduced a double mutation (D100R and R425E) into the penton base sequence of Ad3 that would break up the salt bridge between two neighboring pentons and prevent the assembly of PtDd.31 The penton base mutant (mut-Ad3GFP) is identical to its wild-type counterpart (wt-Ad3GFP) in the efficiency of progeny virus production; however, it is disabled in the production of PtDd. Both viruses contain an identical GFP expression cassette to follow transduced cells. Wt-Ad3 and mut-Ad3 were tested for their antitumor effect in pre-established tumors derived from the human lung cancer cell line A549. A549 tumors form epithelial junctions. This is exemplified by immunofluorescence analysis of A549 tumor sections for the junction proteins E-cadherin and DSG2 (Fig. 1A). Viruses were injected intratumorally into subcutaneous A549 tumors. Two days after injection, tumors were harvested and single-cell suspensions were analyzed for GFP-positive tumor cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 1B). The percentage of GFP-positive cells was comparable for both viruses, indicating that the tumor cell transduction efficacy was similar. To measure viral genome replication in tumors, we performed qPCR using Ad-specific primers on tumor samples harvested at day 1 and 3 after virus injection (Fig. 1C). This study showed a similar increase of viral DNA copy numbers from day 1 to 3, indicating that the initial rounds of viral replication were comparable for both viruses. A functional marker of JO-mediated junction opening in vivo in tumors is shedding of the extracellular domain of DSG2 from the tumor.32 The shed human DSG2 can be measured in the serum by ELISA. In wt-Ad3GFP- and mut-Ad3GFP-injected mice, serum DSG2 levels were comparable for both viruses at 3 hours after intratumoral injection, reflecting some degree of junction opening by the incoming virus (Fig. 1D). However, starting from day 1 p.i., serum DSG2 levels increased significantly faster in mice injected with wt-Ad3GFP compared with mut-AdGFP-injected mice. This supports a direct link between the abilities to produce PtDd and to open epithelial junctions in tumors in vivo. We then tested both viruses for their ability to attenuate tumor growth (Fig. 1E and F). Compared with PBS-injected tumors, both wt-Ad3GFP and mut-Ad3GFP slowed tumor growth to a similar degree during the first two weeks after injection. This is mostly likely because of killing of tumor cells that were transduced by the injected virus. However, at later time points the antitumor effect of mut-Ad3GFP was significant less (p < 0.05) based on the log-rank test of Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Fig. 1F). Based on this, we conclude that the ability to open epithelial junctions correlates with the antitumor efficacy of Ad3.

Figure 1.

Comparison of wt-Ad3GFP and mut-Ad3GFP after intratumoral injection into subcutaneous A549 tumors. (A) Epithelial junctions in A549 tumors. Tumor sections were stained with antibodies specific to the adherens junction protein E-cadherin (red) and the desmosomal junction protein DSG2 (green). Note the characteristic “chicken-wire” staining of membranes with epithelial junctions. The scale bar is 20 μm. (B) Comparison of initial tumor transduction. Two days after intratumoral injection of 4 × 1010 vp of wt-Ad3GFP or mut-Ad3GFP, tumors were harvested and digested with collagenase/dispase, and tumor cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP expression. N = 3. The difference between the two groups is not significant. (C) Comparison of viral genome replication. Tumors were harvested at days 1 and 3 after Ad injection and genomic DNA was isolated. Viral genome copy numbers were measured by qPCR with primers specific to sequences within the viral hexon gene that are conserved between Ad serotypes.63 N = 3 (tumors per group). The differences between the two viruses were not significant. (D) Comparison of DSG2 shedding as a biomarker for Ad3-mediated junction opening. Serum was harvested before Ad injection (“pre”) and 3 hours and 1, 2, and 3 days after Ad injection, and human DSG2 concentrations were measured using antibodies that specifically recognize the shed extracellular domain of DSG2. Background (pre-injection) DSG2 levels were subtracted from the levels measured after Ad injection. N = 3, p < 0.05 starting from day 1. (E and F) Comparison of antitumor effect. When tumors reached a volume of ∼200 mm3, they were injected with PBS, wt-Ad3GFP (4 × 1010 vp), or mut-Ad3GFP (4 × 1010 vp) on day 18 after tumor cell implantation (indicated by vertical arrow). Tumor volumes were measured regularly. (E) Tumor volumes in individual mice. Each line is one animal. (F) Kaplan–Meier survival plot using the day when tumors reached a volume of 750 mm3 as the endpoint. (G) Spread and oncolysis mediated by wt-Ad3GFP and mut-Ad3GFP. Three days after intratumoral injection of 4 × 1010 vp of wt-Ad3GFP or mut-Ad3GFP, tumors were harvested and sections were analyzed for GFP expression (green) and stained with anti-DSG2 antibodies (red). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). The scale bars are 50 μm. Representative sections are shown. Lysis foci were measured by image morphometry. The area of foci in wt-Ad3GFP-injected tumors was significantly larger (p = 0.04).

To visualize oncolysis and the effect on junctions we performed immunofluorescence analysis of tumor sections three days after intratumoral Ad injection (Fig. 1G). Lysis foci in wt-Ad3GFP-injected tumors were significantly larger compared with mut-AdGFP. DSG2 signals between infected (GFP-positive cells) as well as between cells adjacent to the lysis foci were absent in wt-Ad3GFP-injected tumors, indicating PtDd-mediated effects. In contrast, DSG2 signals in mut-Ad3GFP-injected tumor were maintained in cells surrounding the infected area. This underscores that PtDd production is required for junction opening and lateral virus spread.

Recombinant JO enhances antitumor effect of an Ad3 mutant that is disabled for junction opening

To support the hypothesis that long-term tumor control relies on junction opening and intratumoral spread of de novo-produced virions, we co-administered recombinant JO to enhance the antitumor efficacy of mut-Ad3GFP (Fig. 2A and B). Because JO can compete with Ad3 virus transduction, JO was given 1 hour after mut-Ad3GFP injection on three consecutive days. JO injection alone had no significant antitumor effect compared with PBS injection. In mice treated with mut-Ad3GFP plus JO, tumor growth was delayed and survival was significantly prolonged compared with mice that were injected with mut-Ad3GFP only (p < 0.01). In two out of four mice that received the combination treatment, tumors disappeared after day 20, but relapsed 1 week later, suggesting that not all tumor cells had been killed. In contrast, mut-Ad3GFP injection without JO did not stop tumor growth. This study indicates that junction opening is important for antitumor efficacy of Ad3 and that JO can enhance the therapeutic efficacy of mu-Ad3GFP that is disabled to produce PtDd and spread in tumors.

Figure 2.

Effect of JO on antitumor effect of mut-Ad3GFP. When tumors reached a volume ∼100 mm3, PBS, JO (50 μg), mut-Ad3GFP (4 × 1010 vp), or mut-Ad3GFP (4 × 1010 vp) plus JO (50 μg) were injected intratumorally on days 6, 7, and 8 after tumor cell implantation. For the combination treatment, JO was given one hour after mut-Ad3GFP injection. (A) Tumor volumes in individual mice. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival plot using the day when tumors reached a volume of 1000 mm3 as the endpoint. The difference between PBS and JO curves are not significant. The difference between the mut-Ad3GFP and mutAd3GFP + JO groups is significant (p < 0.01).

Effect of recombinant JO on antitumor efficacy of Ads that do not use DSG2 as a receptor

In the Ad3 model, JO competes with the injected virus and de novo-produced virus progeny for the same receptor, DSG2. To further study the effect of JO on oncolytic Ads, we used a replication-competent Ad5 virus containing a CMV-GFP expression cassette (wt-Ad5GFP). Ad5 uses CAR as a receptor and Ad5 transduction is not blocked by JO.24 Furthermore, as outlined above, most clinically used oncolytic Ads are derived from Ad5.

Wt-Ad5GFP was injected either alone or mixed with JO intratumorally into A549 tumor-bearing mice. As expected, wt-Ad5GFP delayed tumor growth (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3A and B). The effect was greatly enhanced when wt-Ad5GFP was combined with JO (p < 0.01; Fig. 3B wt-Ad5GFP vs. wt-Ad5GFP+JO). In this cohort of mice, all of the tumors disappeared for more than 2 weeks after injection. To show that the increased antitumor effect was because of better viral transduction and spread, we harvested tumors 4 days after virus injection and evaluated GFP expression on tumor sections (Fig. 3C). Sections of tumors from mice injected with wt-Ad5GFP + JO showed larger foci with central necrosis and GFP expression than tumors from wt-Ad5GFP-injected animals. Staining of tumor sections for E-cadherin (Fig. 3C, red signals) suggested that junctions around wt-Ad5GFP + JO-infected cells were absent, whereas they were visible as yellow E-cadherin/GFP co-staining in tumors injected with wt-Ad5GFP only. Intravenous injection of wt-Ad5GFP was not possible because of Ad5 liver tropism and potential severe hepatoxicity.

Figure 3.

Effect of JO on antitumor activity of replication-competent wt-Ad5GFP virus injected intratumorally. When A549 tumors reached a volume of ∼200 mm3, JO (50 μg), wt-Ad5GFP (4 × 1010 vp), or wt-Ad5GFP (4 × 1010 vp) plus JO (50 μg) were injected intratumorally on days 8, 9, and 10 after tumor cell implantation. (A) Tumor volumes in individual mice. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival plot using the day when tumors reached a volume of 500 mm3 as the endpoint. The difference between the wt-Ad5GFP and wtAd5GFP + JO groups is significant (p < 0.01). (C) GFP fluorescence (green) on section of tumors harvested at day 4 after the last injection. Sections were also stained for the junction protein E-cadherin (red). Representative sections are shown. The scale bar is 20 μm.

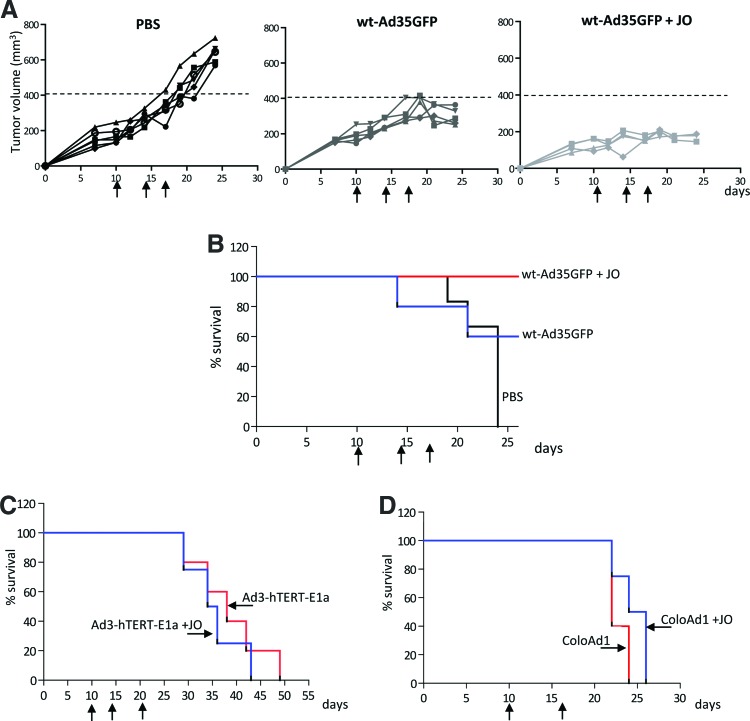

The species B Ad serotype 35 (Ad35) uses CD46 as a receptor49 and is also not blocked by JO. Furthermore, Ad35 can be safety injected intravenously. Mizuguchi's group has shown that intravenous injection of an Ad35 vector caused only minimal transduction (only detectable by PCR) of tissues, including the liver, in human CD46 transgenic mice50 and nonhuman primates.51 A potential explanation for this is that Ad5 entry into hepatocytes is mediated by Ad5 hexon protein interaction with coagulation factor X.52,53 This pathway is, however, inefficient if Ads contain short fibers such as Ad3, Ad35, or Ad11, most likely because of a sterical block of the factor X-interacting domains within the Ad hexon.54 We applied a replication-competent, GFP-expressing Ad35 virus (wt-Ad35GFP) intravenously in mice with pre-established A549 tumors (Fig. 4A and B). In the combination cohort, JO was given intravenously one hour before wt-Ad35GFP based on previous intravenous treatment protocols used for monoclonal antibodies and chemotherapy drugs.19,33 As seen in the wt-Ad5GFP study, JO significantly increased the antitumor efficacy of intravenously injected wt-Ad35GFP (p < 0.01; Fig. 4B wt-Ad35GFP vs. wt-Ad35GFP+JO).

Figure 4.

Effect of JO on antitumor activity of replication-competent wt-Ad35GFP and conditionally replicating Ad3-hTERT-E1A and ColoAd1 after intravenous injection. (A and B) Studies with wt-Ad35GFP. Mice with pre-established A549 tumors (∼200 mm3) were intravenously injected with JO (50 μg) followed 1 hr later by wt-Ad35GFP (4 × 1010 vp) or with wt-Ad35GFP alone. The treatment cycle was repeated 4 and 7 days later. (A) Tumor volumes in individual mice. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival plot using the day when tumors reached a volume of 400 mm3 as the endpoint. The difference between the wt-Ad35GFP and wtAd35GFP + JO groups is significant (p < 0.01). (C) Studies with a conditionally replication Ad3 serotype-based vector (Ad3-hTERT-E1A) in mice with subcutaneous A549 tumors. Ad3 uses DSG2 as a receptor. Treatment was performed as described for wt-Ad35GFP. Shown is the Kaplan–Meier survival plot using the day when tumors reached a volume of 1000 mm3 as the endpoint. The difference between the two groups is not significant. (D) Studies with a conditionally replicating chimeric Ad3-Ad11 virus (ColoAd1). When colon cancer HT-29 tumors reached a volume of 200 mm3, JO followed by ColoAd1 (4 × 1010 vp) or ColoAd1 alone (4 × 1010 vp) were injected intravenously. Treatment was repeated 7 days later. Shown is the Kaplan–Meier survival plot using the day when tumors reached a volume of 1000 mm3 as the endpoint. The difference between the two groups is not significant. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum

Effect of recombinant JO on antitumor efficacy of conditionally replicating Ads that do use DSG2 as a receptor

While the studies with wt-Ad5GFP and wt-Ad35GFP showed that JO increases the oncolytic efficacy of Ads that do not use DSG2 as a receptor, we also performed the reverse experiment, that is, a combination of JO with DSG2-interacting Ads after intravenous injection. We used two conditionally replicating oncolytic viruses. The first virus, Ad3-hTERT-E1A, is a fully serotype 3-based oncolytic Ad containing an hTERT promoter inserted in front of the Ad3 E1A gene to restrict viral replication to tumor cells.40 Ad3-hTERT-E1A was intravenously injected alone or in combination with JO into mice with pre-established A549 tumors (Fig. 4C). There was no significant difference in survival between the two groups, which is explicable on the basis that junction opening is already optimal in Ad3-hTERT-E1A. The second virus, ColoAd1, is a chimeric Ad11/Ad3 virus developed using a direct evolution technology on colon cancer cells.39 ColoAd1 contains Ad11 fibers that target the virus to two receptors, CD46 and DSG2.24,38,49 We used a subcutaneous tumor model derived from colon cancer HT-29 cells and found no significant differences between the groups after intravenous treatment. We speculate that similar to wt-Ad3 and wt-Ad11,31 ColoAd1 also forms PtDd that enable junction opening.

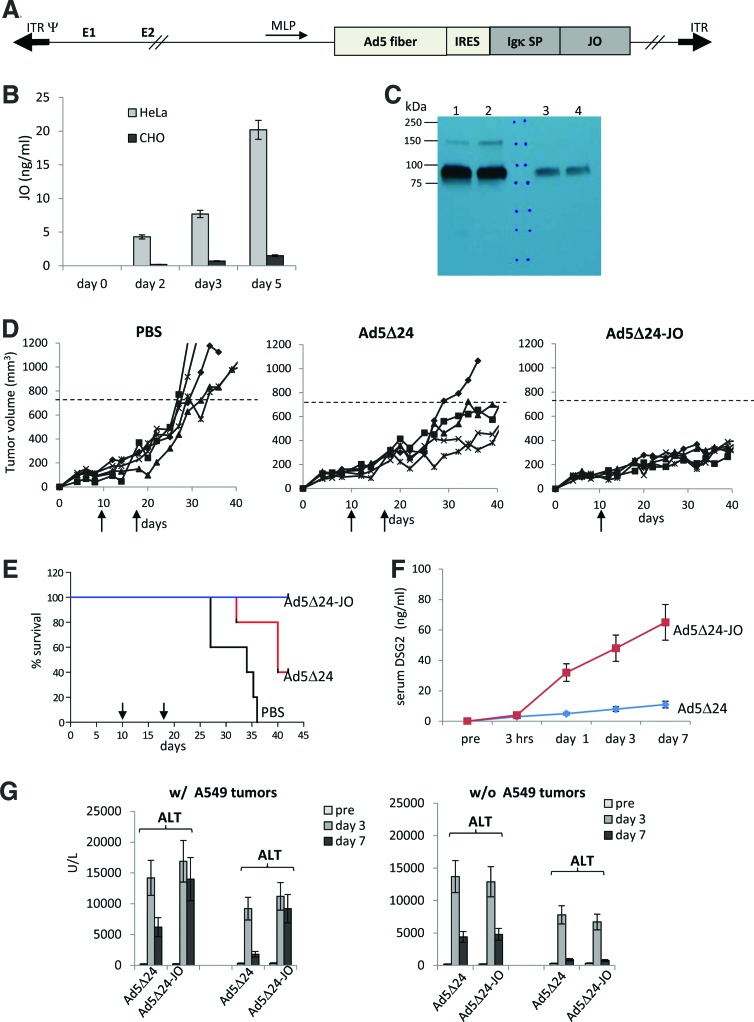

Generation and functional evaluation of an Ad5-based oncolytic virus expressing a secreted form of JO upon replication in tumor cells

To further prove that JO-mediated junction opening improves the efficacy of oncolytic Ads, we genetically modified a conditionally replicating Ad5 vector to express JO. Modifications were based on the Ad5Δ24 virus, which has been widely used in preclinical and clinical studies.55–57 We inserted the coding sequence of a secretable JO linked to an IRES downstream of the fiber gene (Fig. 5A). Upon viral DNA replication, the fiber gene and the other late coding regions are transcribed from the major late promoter (MLP) as a single large mRNA, which is subsequently processed by differential poly A sites utilization and alternative splicing into distinct mRNAs.58 The JO sequence was inserted into the Ad5Δ24 genome so that it would be produced as one bicistronic fiber-JO mRNA. The IRES confers the separate production of JO and fiber proteins. The latter is important for efficient virion assembly. The JO reading frame contained an Igκ signal peptide allowing for JO secretion. Because it is controlled by the MLP, JO is produced only late in the infection cycle, and therefore potential JO cytotoxicity should not greatly affect virus production. In support of this, we found similar production yields in 293 cells for the parental Ad5Δ24 virus and for Ad5Δ24-JO.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of Ad5Δ24-JO. (A) Schematic genome structure of Ad5Δ24-JO. ITR-, Ad inverted terminal repeats; Ψ-, Ad packaging signal; E1, E2-early regions; MLP, major late promoter; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; Igκ-SP, immunoglobulin kappa light chain signal peptide; JO, JO reading frame comprising the K-coil dimerization domain and the affinity-enhanced Ad3 fiber knob.34,64 (B) JO concentrations in culture supernatant of transduced cells. Ad5 replication-permissive HeLa cells and non-replication-permissive CHO cells were transduced with Ad5Δ24-JO at an MOI of 100 vp/cell and JO concentrations were measured in filtered culture supernatant. Note that this MOI did not cause cytopathic effect in HeLa cells before day 4 postinfection. N = 3. (C) Western blot analysis of JO using recombinant DSG2 as a probe. HeLa cells and culture medium were collected at day 3 after infection. A total of 20 μl of cell lysate (of 106 cells in 1 ml) and 20 μl of culture supernatant was used for Western blot. Lanes 1 and 2: cell lysate; lanes 3 and 4: culture supernatant. (D and E) Antitumor effect of Ad5Δ24-JO. At day 10 after tumor cell implantation, when A549 tumors reached a volume of ∼100 mm3, Ad5Δ24-JO (4 × 1010 vp) was injected intravenously. Serum samples were collected before injection and 3 hours, and 1, 3, and 7 days after injection. After the last serum collection, a second injection of Ad5Δ24-JO (4 × 1010 vp) was given. (D) Tumor volumes in individual mice. (E) Kaplan–Meier survival plot using the day when tumors reached a volume of 750 mm3 as the endpoint. (F) Serum concentrations of shed DSG2. DSG2 was measured by ELISA. N ≥ 4. (G) Serum levels of liver alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). N ≥ 4. p < 0.01 for day 7 Ad5Δ24 versus Ad5Δ24-JO. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum

Replication-dependent production of secreted JO was studied in HeLa cells, that is, a human cancer cell line that supports replication of Ad5 and in Chinese hamster ovarian cells (CHO cells), that is, cells that are not permissive for Ad5 replication.59,60 Cells were infected at a low MOI of 100 vp/cell and secreted JO was measured by ELISA in filtered culture supernatant (Fig. 5B). Transduction rates of both cell lines were comparable based on qPCR titering of Ad genomes in infected cells at day 1 after infection (data not shown). JO concentrations in the supernatant increased in infected HeLa cells over time to a greater degree than in infected CHO cells. Western blot analysis of HeLa cell lysates and supernatants with Ad3-fiber knob-specific monoclonal antibodies showed signals that corresponded to the expected molecular weight of JO (Fig. 5C).

We then tested Ad5Δ24 and Ad5Δ24-JO after two intravenous injections (on day 10 and 17 after tumor cell implantation) in mice with pre-established subcutaneous A549 tumors (Fig. 5D and E). This treatment protocol was based on clinical trials in which an oncolytic Ad was given in repeatedly.61 Our study demonstrated significantly stronger antitumor efficacy of Ad5Δ24-JO. We also used the animals from this study to collect serum samples before and 3 hr and 1, 3, and 7 days after the first virus injection. Serum concentrations of shed DSG2 were significantly higher in mice that received Ad5Δ24-JO, indicating JO-mediated junction opening (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, serum samples were analyzed for liver transaminase levels to assess the safety profile of the two viruses (Fig. 5G, left panel). Both vectors triggered hepatocellular damage. However, the transaminase levels at day 7 were significantly higher after Ad5Δ24-JO injection. We previously showed that JO does not increase drug uptake in the liver, indicating that it does not act on hepatocellular junctions.36 We therefore speculate that the continuing liver damage seen in Ad5Δ24-JO-injected animals is because of more efficient production/spread and release into the blood stream of de novo-produced virions that then infect the liver. This suggests that the improved antitumor efficacy of Ad5Δ24-JO comes at the price of more severe liver damage. To support this conclusion, we injected Ad5Δ24-JO and Ad5Δ24 into mice without A549 xenograft tumors (Fig. 5G, right panel). This study also showed comparable virus-associated liver toxicity at day 3, but no greater transaminase levels for Ad5Δ24-JO at day 7.

We conclude that Ad serotypes or derivatives that produce PtDd or JO but do not transduce liver (e.g., Ad3, 11, 14) might be more suitable as platforms for new oncolytic Ads. In this context, a study with an oncolytic vector based on Ad3 is notable.62 In this study, 25 patients with chemotherapy refractory cancer were treated intravenously with a fully serotype 3-based oncolytic Ad Ad3-hTERT-E1A. The only grade 3 adverse reactions observed were self-limiting cytopenias. Neutralizing antibodies against Ad3 increased in all patients. Signs of possible efficacy were seen in 11/15 (73%) patients evaluable for tumor markers. Particularly promising results were seen in breast cancer patients and especially those receiving concomitant trastuzumab. The latter might suggest that Ad3 acts in a similar way to JO on tumor junctions and increases drug penetration.

Our finding that co-administration of recombinant JO increases the antitumor efficacy of Ads is relevant for the virotherapy of epithelial tumors with other classes of oncolytic viruses, including HSV1, measles virus, reovirus, vaccinia virus, or coxsackie A21 virus.

Recently, there has been increasing attention on oncolytic viruses as a primer for antitumor immune responses.1,2 The idea is that local application of oncolytic viruses mediates tumor cell lysis, thus releasing tumor antigens. In the context of the proinflammatory local cytokine milieu triggered by the virus, this can activate systemic immune responses that target the primary tumor as well as metastatic sites. There is the opinion that the immunostimulatory effect of viral oncolysis does not require intratumoral viral spread. This opinion, however, does not consider the phenotypic heterogeneity and genetic instability of tumor cells in a given tumor, which implies that the spectrum of tumor-related antigenic epitopes varies between tumor cells or tumor cell clones and that the lysis of tumor cells in different areas of the tumor is required to achieve a broad antitumor immune response.63,64 Our preliminary data indicate that JO has also the potential to improve antitumor immune responses by unmasking tumor antigens that are trapped in epithelial junctions and by facilitating intratumoral penetration of immune cells.33 Therefore, JO co-therapy might increase the activation of antitumor immune responses triggered by oncolytic viruses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 CA080192 (A.L.) and R01 HLA078836 (A.L.), and the Pacific Ovarian Cancer Research Consortium/Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Ovarian Cancer Grant P50 CA83636, a grant from BRIM Biotechnology, Inc., and a grant from Samyang Biopharmaceuticals Corporation.

Author Disclosure

A.L. and D.C. are co-owners of Compliment Corp., a start-up company that is involved in the clinical development of the JO technology.

References

- 1.Uusi-Kerttula H, Hulin-Curtis S, Davies J, Parker AL. Oncolytic adenovirus: Strategies and insights for vector design and immuno-oncolytic applications. Viruses 2015;7:6009–6042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamarin D, Pesonen S. Replication-competent viruses as cancer immunotherapeutics: Emerging clinical data. Hum Gene Ther 2015;26:538–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turnbull S, West EJ, Scott KJ, et al. Evidence for oncolytic virotherapy: Where have we got to and where are we going? Viruses 2015;7:6291–6312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biedermann K, Vogelsang H, Becker I, et al. Desmoglein 2 is expressed abnormally rather than mutated in familial and sporadic gastric cancer. J Pathol 2005;207:199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harada H, Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, et al. Abnormal desmoglein expression by squamous cell carcinoma cells. Acta Derm Venereol 1996;76:417–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leech AO, Cruz RG, Hill AD, Hopkins AM. Paradigms lost-an emerging role for over-expression of tight junction adhesion proteins in cancer pathogenesis. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi IK, Strauss R, Richter M, et al. Strategies to increase drug penetration in solid tumors. Front Oncol 2013;3:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2001;46:3–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavin SR, McWhorter TJ, Karasov WH. Mechanistic bases for differences in passive absorption. J Exp Biol 2007;210:2754–2764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green SK, Karlsson MC, Ravetch JV, Kerbel RS. Disruption of cell-cell adhesion enhances antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity: Implications for antibody-based therapeutics of cancer. Cancer Res 2002;62:6891–6900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turley EA, Veiseh M, Radisky DC, Bissell MJ. Mechanisms of disease: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-does cellular plasticity fuel neoplastic progression? Nat Clin Pract 2008;5:280–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christiansen JJ, Rajasekaran AK. Reassessing epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a prerequisite for carcinoma invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res 2006;66:8319–8326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiery JP, Lim CT. Tumor dissemination: An EMT affair. Cancer Cell 2013;23:272–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fessler SP, Wotkowicz MT, Mahanta SK, Bamdad C. MUC1* is a determinant of trastuzumab (Herceptin) resistance in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;118:113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveras-Ferraros C, Vazquez-Martin A, Cufi S, et al. Stem cell property epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a core transcriptional network for predicting cetuximab (Erbitux) efficacy in KRAS wild-type tumor cells. J Cell Biochem 2011;112:10–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CM, Tannock IF. The distribution of the therapeutic monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and trastuzumab within solid tumors. BMC Cancer 2010;10:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tannock IF, Lee CM, Tunggal JK, et al. Limited penetration of anticancer drugs through tumor tissue: A potential cause of resistance of solid tumors to chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:878–884 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:583–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beyer I, Cao H, Persson J, et al. Coadministration of epithelial junction opener JO-1 improves the efficacy and safety of chemotherapeutic drugs. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:3340–33451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyle AH, Baker JH, Gandolfo MJ, et al. Tissue penetration and activity of camptothecins in solid tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther 2014;13:2727–2737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mugabe C, Matsui Y, So AI, et al. In vivo evaluation of mucoadhesive nanoparticulate docetaxel for intravesical treatment of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:2788–2798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramesh N, Memarzadeh B, Ge Y, et al. Identification of pretreatment agents to enhance adenovirus infection of bladder epithelium. Mol Ther 2004;10:697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vera B, Martinez-Velez N, Xipell E, et al. Characterization of the antiglioma effect of the oncolytic adenovirus VCN-01. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Li ZY, Liu Y, et al. Desmoglein 2 is a receptor for adenovirus serotypes 3, 7, 11 and 14. Nat Med 2011;17:96–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Excoffon KJ, Bowers JR, Sharma P. Alternative splicing of viral receptors: A review of the diverse morphologies and physiologies of adenoviral receptors. Recent Res Dev Virol 2014;9:1–24 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam E, Falck-Pedersen E. Unabated adenovirus replication following activation of the cGAS/STING-dependent antiviral response in human cells. J Virol 2014;88:14426–14439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chitaev NA, Troyanovsky SM. Direct Ca2+-dependent heterophilic interaction between desmosomal cadherins, desmoglein and desmocollin, contributes to cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol 1997;138:193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trotman LC, Achermann DP, Keller S, et al. Non-classical export of an adenovirus structural protein. Traffic 2003;4:390–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greber UF. Virus assembly and disassembly: The adenovirus cysteine protease as a trigger factor. Rev Med Virol 1998;8:213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fender P, Boussaid A, Mezin P, Chroboczek J. Synthesis, cellular localization, and quantification of penton-dodecahedron in serotype 3 adenovirus-infected cells. Virology 2005;340:167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu ZZ, Wang H, Zhang Y, et al. Penton-dodecahedral particles trigger opening of intercellular junctions and facilitate viral spread during adenovirus serotype 3 infection of epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Ducournau C, Saydaminova K, et al. Intracellular signaling and desmoglein 2 shedding triggered by human adenoviruses Ad3, Ad14, and Ad14P1. J Virol 2015;89:10841–10859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beyer I, van Rensburg R, Strauss R, et al. Epithelial junction opener JO-1 improves monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Cancer Res 2011;71:7080–7090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Beyer I, Persson J, et al. A new human DSG2-transgenic mouse model for studying the tropism and pathology of human adenoviruses. J Virol 2012;86:6286–6302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Li Z, Yumul R, et al. Multimerization of adenovirus serotype 3 fiber knob domains is required for efficient binding of virus to desmoglein 2 and subsequent opening of epithelial junctions. J Virol 2011;85:6390–6402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richter M, Yumul R, Wang H, et al. Preclinical safety and efficacy studies with an affinity-enhanced epithelial junction opener and PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2015;2:15005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Liaw YC, Stone D, et al. Identification of CD46 binding sites within the adenovirus serotype 35 fiber knob. J Virol 2007;81:12785–12792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuve S, Wang H, Ware C, et al. A new group B adenovirus receptor is expressed at high levels on human stem and tumor cells. J Virol 2006;80:12109–12120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuhn I, Harden P, Bauzon M, Hermiston T. ColoAd1, a chimeric Ad11/Ad3 oncolytic virus for the treamtment of colon cancer. Mol Ther 2005;11:S124 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hemminki O, Bauerschmitz G, Hemmi S, et al. Preclinical and clinical data with a fully serotype 3 oncolytic adenovirus Ad3-hTERT-E1A in the treatment of advanced solid tumors.. Mol Ther 2010;18:S74 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bett AJ, Krougliak V, Graham FL. DNA sequence of the deletion/insertion in early region 3 of Ad5 dl309. Virus Res 1995;39:75–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong AS, Yao QH, Peng RH, et al. A simple, rapid, high-fidelity and cost-effective PCR-based two-step DNA synthesis method for long gene sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2004;32:e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakurai F, Mizuguchi H, Yamaguchi T, Hayakawa T. Characterization of in vitro and in vivo gene transfer properties of adenovirus serotype 35 vector. Mol Ther 2003;8:813–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu ZZ, Zou XH, Dong LX, et al. Novel recombinant adenovirus type 41 vector and its biological properties. J Gene Med 2009;11:128–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warming S, Costantino N, Court DL, et al. Simple and highly efficient BAC recombineering using galK selection. Nucleic Acids Res 2005;33:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tuve S, Chen BM, Liu Y, et al. Combination of tumor site-located CTL-associated antigen-4 blockade and systemic regulatory T-cell depletion induces tumor-destructive immune responses. Cancer Res 2007;67:5929–5939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strauss R, Li ZY, Liu Y, et al. Analysis of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in ovarian cancer reveals phenotypic heterogeneity and plasticity. PLoS One 2011;6:e16186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richter M, Yumul R, Wang H, et al. Preclinical safety and efficacy studies with an affinity-enhanced epithelial junction opener and PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin. Mol Ther 2015;2:15005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaggar A, Shayakhmetov D, Lieber A. CD46 is a cellular receptor for group B adenoviruses. Nat Med 2003;9:1408–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakurai F, Kawabata K, Koizumi N, et al. Adenovirus serotype 35 vector-mediated transduction into human CD46-transgenic mice. Gene Ther 2006;13:1118–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakurai F, Nakamura S, Akitomo K, et al. Transduction properties of adenovirus serotype 35 vectors after intravenous administration into nonhuman primates. Mol Ther 2008;16:726–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shayakhmetov DM, Gaggar A, Ni S, et al. Adenovirus binding to blood factors results in liver cell infection and hepatotoxicity. J Virol 2005;79:7478–7491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waddington SN, McVey JH, Bhella D, et al. Adenovirus serotype 5 hexon mediates liver gene transfer. Cell 2008;132:397–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y, Wang H, Yumul R, et al. Transduction of liver metastases after intravenous injection of Ad5/35 or Ad35 vectors with and without factor X-binding protein pretreatment. Hum Gene Ther 2009;20:621–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fueyo J, Gomez-Manzano C, Alemany R, et al. A mutant oncolytic adenovirus targeting the Rb pathway produces anti-glioma effect in vivo. Oncogene 2000;19:2–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cascallo M, Alonso MM, Rojas JJ, et al. Systemic toxicity-efficacy profile of ICOVIR-5, a potent and selective oncolytic adenovirus based on the pRB pathway. Mol Ther 2007;15:1607–1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nokisalmi P, Pesonen S, Escutenaire S, et al. Oncolytic adenovirus ICOVIR-7 in patients with advanced and refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:3035–3043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shenk T. Adenoviridea. In: Fields Virology, vol. 2 Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. (Lippincott-Raven Publisher, Philadelphia: ). 1996; pp. 2111–2148 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bernt K, Liang M, Ye X, et al. A new type of adenovirus vector that utilizes homologous recombination to achieve tumor-specific replication. J Virol 2002;76:10994–11002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steinwaerder DK, Carlson CA, Lieber A. DNA replication of first-generation adenovirus vectors in tumor cells. Hum Gene Ther 2000;11:1933–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vassilev L, Ranki T, Joensuu T, et al. Repeated intratumoral administration of ONCOS-102 leads to systemic antitumor CD8 T-cell response and robust cellular and transcriptional immune activation at tumor site in a patient with ovarian cancer. Oncoimmunology 2015;4:e1017702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hemminki O, Diaconu I, Cerullo V, et al. Ad3-hTERT-E1A, a fully serotype 3 oncolytic adenovirus, in patients with chemotherapy refractory cancer. Mol Ther 2012;20:1821–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fox EJ, Loeb LA. Cancer: One cell at a time. Nature 2014;512:143–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalaora S, Barnea E, Merhavi-Shoham E, et al. Use of HLA peptidomics and whole exome sequencing to identify human immunogenic neo-antigens. Oncotarget 2016;7:5110–5117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]