To the Editor

For many patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs), bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is curative with healthy donor-derived immunity.1 Patients with PID often develop pulmonary complications secondary to recurrent infections2; however, those with severe lung disease have been ineligible for even reduced-intensity conditioning because of the high risk of mortality. In parallel, patients with PID with lung failure have been ineligible for bilateral orthotopic lung transplant (BOLT) because of futility concerns of recurrent infections destroying the new lungs. Below, we describe a novel strategy that we designed for a teenager in pulmonary failure due to combined immunodeficiency disease. We hypothesized that persistent engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells from an immunocompetent lung donor would result in the establishment of donor-derived cellular immunity that would prevent recurrent infections and may also enable lifelong tolerance.

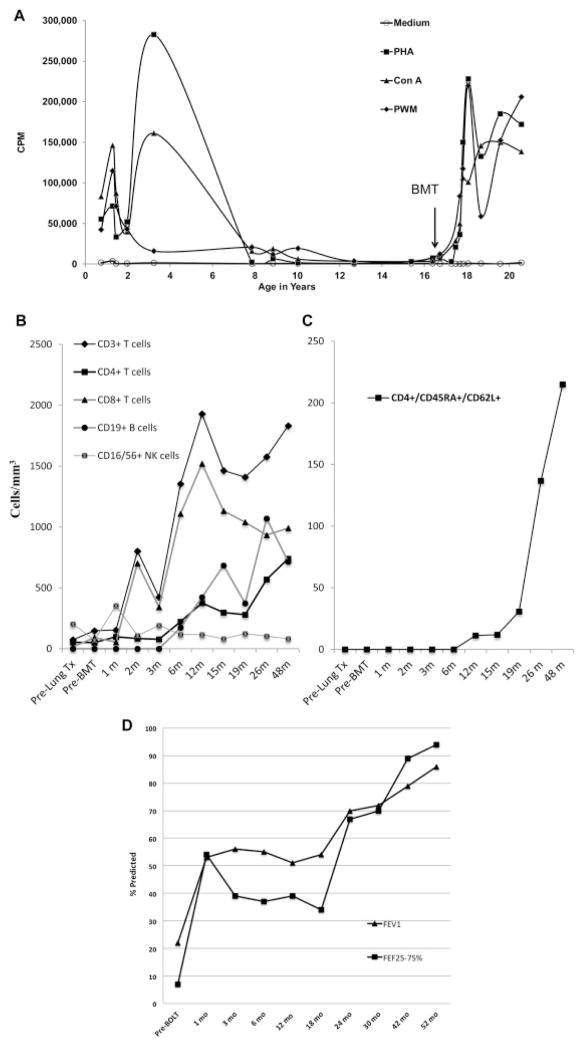

A 16-year-old girl was diagnosed with T-cell lymphopenia after birth when she was tested as a possible BMT donor for her older brother suffering from combined immunodeficiency disease. She had low but significant proliferative response to mitogens (Fig 1, A), normal levels of IgG and IgM, but undetectable levels of IgA (not shown). She developed recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections at age 9 years. Pulmonary function tests revealed forced vital capacity (FVC) of 75%, FEV1 of 66%, and forced expiratory flow at 25% to 75% of FVC of 61% of predicted. Recognizing her declining immune competence and early bronchiectasis, BMT was recommended but not pursued in the absence of suitable donors. The genetic diagnosis of her PID is pending by whole exome sequencing.

Fig 1.

A, T-cell immunity as assessed by mitogen responses on a chronological scale. The y-axis shows counts per minute (CPM) following 3 H-thymidine incorporation and measured as previously described.6 PBMCs were stimulated with PHA, pokeweed mitogen (PWM), concanavalin A (ConA), or medium alone as negative control. B, Lymphocyte reconstitution. Absolute numbers of lymphocyte subsets per μL/mm3 were measured as previously described7 from whole blood. C,Tempo of thymopoiesis is depicted by the absolute number of CD4+ T cells over time that display the combinatorial markers of “naive” T-cell immunophenotype (CD45RA/CD62L coexpression). D, Pulmonary function tests before and after BOLT. FEV1 and forced expiratory flow rates at 25% to 75% of FVC (FEF25-75) as measured by standard spirometry.

Despite rotating prophylactic antibiotics and intravenous imunoglobulin, she developed Pseudomonas bronchitis at age 11 years. She developed Pneumococcal pneumonia at age 13 years, and her sputum grew Aspergillus fumigatus and Mycobacterium avium intracellulare. Recurrent gastroenteritis and growth failure necessitated total parental nutrition at age 15 years. At age 16 years, the patient presented to us in a wheelchair with severe respiratory distress and a year history of oxygen dependence (1–2 L/min) along with FEV1 of 20% and forced expiratory flow at 25% to 75% of FVC of 6% of predicted. Bronchoscopy revealed tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia. Cultures grew multidrug-resistant Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. She had molluscum contagiosum, Microsporidia infection, and recurrent varicella-zoster virus. A single patient protocol proposing BOLT and BMT from the same donor with a minimum of 2 of 6 HLA match was approved by the local institutional review board and the Food and Drug Administration in November 2009. An ABO-matched, 5 of 10 HLA-matched (see Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org), cytomegalovirus (CMV)-seropositive, African American female donor was identified in 4 weeks through the United Network of Organ Sharing. Before solid organ procurement, the beating-heart donor underwent external iliac crest marrow harvest. A total of 700 mL of bone marrow underwent CD3/CD19 T-cell and B-cell depletion (CliniMACS, Miltenyi Biotec, Cambridge, Mass) and 13 × 109 total nucleated cells with 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg and 2 × 104 CD3+ T cells/kg was cryopreserved. Rituximab was administered monthly (375 mg/m2/dose) starting pre-BOLT until a month after BMT to prevent HLA sensitization and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. She received standard immunosuppression including methylprednisone (500 mg/dose × 2) before reperfusion of each lung, basiliximab (days 0 and 4), and azathioprine (1 month) along with tacrolimus and prednisone with standard taper. One week after lung transplantation she was discharged on room air. Her pulmonary function tests have steadily improved ever since (Fig 1, D). Three months after BOLT, having also undergone Nissen fundoplication for acid reflux after BOLT, she was medically cleared to start BMT conditioning while continuing daily tacrolimus and post-BOLT antimicrobial prophylaxis. First, hydroxyurea (30 mg/kg/dose) was administered daily between days −27 and −3 to induce cycling and chemosensitization of the stem cell pool.3 As rejection prophylaxis before a T-cell–depleted graft, a single dose of alemtuzumab (0.5 mg/kg) was given on day −10 to deplete host natural killer cells. Further doses were not given to avoid lymphodepleting levels post-BMT. The patient was admitted on day −4 and horse antithymocyte globulin (30 mg/kg/dose) was given on days −3, −2, 1, and +1 for maximum host and donor T-cell depletion in the multiple HLA-mismatched setting. Hematopoietic stem cell toxic therapy was limited to thiotepa (200 mg/m2) on day −2 followed by a single fraction of total body irradiation (200 cGy) with lung shielding on day −1. On day 0, freshly thawed bone marrow was infused.

Because of Stenotrophomonas colonization, during the predicted neutropenia she received prophylactic maternal granulocytes. She was discharged fully ambulatory on day +20 on room air with 100% donor chimerism. Serial surveillance lung biopsies have found no evidence of immune rejection and she has continued with 100% donor chimerism in whole blood, CD3+/T-cell, and CD33+/myeloid fractions over 4 years post-BMT. During the first months after BMT, she had low-grade CMV reactivation. She became total parental nutrition and gastrojejunal feed independent; however, stage IV gut graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) developed 4.5 months post-BMT after contracting Norovirus gastroenteritis, which abruptly resulted in undetectable tacrolimus levels. GVHD rapidly resolved after a single dose of infliximab and low-dose steroids (1 mg/kg/d of methylprednisone × 5 days followed by aggressive taper). After months without GVHD, tacrolimus wean was initiated and completed 16 months post-BMT (June 2011). With CMV-specific T-cell immunity present (see below) and undetectable virus, CMV prophylaxis was discontinued 8 months after BMT without subsequent reactivation. Molluscum resolved by 1 year and fungal, pneumocystis, and varicella-zoster virus prophylaxis was stopped 18 months post-BMT. She has been attending college, running 5k races, and has been free from immunosuppression for more than 3 years.

Natural killer and CD8+ T cells normalized4 and 5 by 1 to 2 months after BMT while CD4+ T-cell recovery was delayed until 6 months (Fig 1, B). Nevertheless, CMV-specific T-cell responses were detectable by 4.5 months post-BMT with a stimulation index of 61 and robust IFN-γ, TNF-α secretion (536.5 pg/mL and 11.4 pg/mL, respectively). Post rituximab, there was a gradual recovery of CD19+ B cells (Fig 1, B). Serum immunoglobulin levels normalized by 6 months (IgM, 107 mg/dL; IgA, 64 mg/dL; IgE, 5 IU/mL). Besides normal isohemagglutinins, vaccination resulted in protective antibody titers against diphtheria (0.21 IU/mL) and tetanus (1.19 IU/mL). By flow cytometry, recent thymic emigrants were absent for over a year post-BMT ( Fig 1, C). T-cell receptor excision circles were undetectable pre-BMT until 18 months post-BMT, when they measured 1036 signal-joint T-cell receptor excision circles/105 T cells. De novo thymopoiesis was confirmed when the severely restricted/oligoclonal pre-BMT T-cell receptor Vβ repertoire (see Fig E1, A, in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org) was replaced with a polyclonal repertoire at 18 months (Fig E1, B). 8 and 9

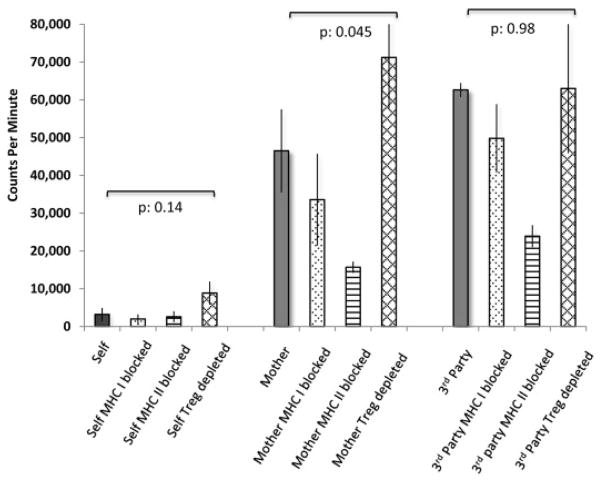

We used in vitro functional assays to probe for mechanisms of tolerance. Purified donor T cells 12 months post-BMT demonstrated decreased proliferation and inflammatory cytokine secretion against host-derived EBV/lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL), sharply contrasting with the strong alloreactivity against haplotype-mismatched maternal or third-party donor. Neither HLA-class-I nor class-II blockade or regulatory T-cell depletion by IL-2 immunotoxin affected antirecipient hyporeactivity of cytokine production and T-cell proliferation, while IL-10 level was unmeasurable ( Fig 2; see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). These data support central clonal deletion in the context of a T-cell–depleted stem cell graft. In sum, we report the first successful case of cadaveric lung transplantation with long-term graft survival, independent of any immunosuppression. The novel BMT reduced-intensity conditioning regimen is well tolerated after BOLT and can lead to durable multilineage engraftment. Prospective clinical trials will be able to test the translational applicability of our novel conceptual framework of cryopreserved T-cell–depleted cadaveric BMT with a flexible timing following solid organ transplant for tolerance induction in other diseases and organs as a result of donor-derived immunocompetence.

Figure 2.

Proliferative responses and cytokine secretion of donor T cells. Negatively selected (Easysep, Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Calif) >95% pure CD3+ T cells (1 × 10−5 cells/well) isolated from the recipient (100% donor) 1 year after BMT (in vivo tacrolimus levels ~3–4 ng/dL range) were cocultured for 5 days with 1 × 10−4 cells/well of EBV/LCL from the indicated sources. To analyze restriction elements in alloreactivity, EBV/LCLs were opsonized at 2 μg/mL with MHC class-I or class-II–blocking antibodies (clones W632 and L243, Bio-Legend Leaf, San Diego, Calif) before coculture. The impact of regulatory T-cell removal was assayed by depleting CD25+ cells among responders with IL-2 immunotoxin as previously described.7 Lung/marrow donor-derived EBV/LCL was not available to be tested as antigen-presenting cells. Culture supernatant was collected and cryopreserved for batched cytokine analysis by luminex assay on a Bio-Plex 200 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif) (see Table E2). Immediately thereafter, T-cell proliferation was quantitated (counts per minute) by 3 H-thymidine incorporation7 and depicted on the y-axis. Significance was tested as indicated by paired 2-tailed Student t test.

Pretransplant immunoscope and sjTREC monitoring was performed in the Duke Human Vaccine Institute Host Response Monitoring Shared Resource Facility (Durham, NC). Post-transplant immunoscope analysis was performed in part at the Genomics and Proteomics Core Laboratories, University of Pittsburgh. We are indebted to the dedicated work of Stem Cell Lab technologists and clinical staff at Duke University Medical Center. We appreciate the critical reading of the manuscript by Mark Vander Lugt.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to P.S. (grant no. 1RO1HL091749).

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: P. Szabolcs has received research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. R. H. Buckley is employed by Duke University Medical Center. J. Voynow is employed by Virginia Commonwealth University and has received research support from the National Institutes of Health and the Virginia Commonwealth Health Research Board. D. W. Zaas has received royalties from UpToDate. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Szabolcs P, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Fischer A, Veys P. Bone marrow transplantation for primary immunodeficiency diseases. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:207–237. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Notarangelo LD, Plebani A, Mazzolari E, Soresina A, Bondioni MP. Genetic causes of bronchiectasis: primary immune deficiencies and the lung. Respiration. 2007;74:264–275. doi: 10.1159/000101784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchida N, Friera AM, He D, Reitsma MJ, Tsukamoto AS, Weissman IL. Hydroxyurea can be used to increase mouse c-kit+Thy-1. 1(lo)Lin-/loSca-1(+) hematopoietic cell number and frequency in cell cycle in vivo. Blood. 1997;90:4354–4362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comans-Bitter WM, de Groot R, van den Beemd R, Neijens HJ, Hop WC, Groeneveld K, et al. Immunophenotyping of blood lymphocytes in childhood: reference values for lymphocyte subpopulations. J Pediatr. 1997;130:388–393. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shearer WT, Rosenblatt HM, Gelman RS, Oyomopito R, Plaeger S, Stiehm ER, et al. Lymphocyte subsets in healthy children from birth through 18 years of age: the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1009 study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckley RH, Schiff SE, Sampson HA, Schiff RI, Markert ML, Knutsen AP, et al. Development of immunity in human severe primary T cell deficiency following haploidentical bone marrow stem cell transplantation. J Immunol. 1986;136:2398–2407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szabolcs P, Park KD, Marti L, Deoliveria D, Lee YA, Colvin MO, et al. Superior depletion of alloreactive T cells from peripheral blood stem cell and umbilical cord blood grafts by the combined use of trimetrexate and interleukin-2 immunotoxin. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:772–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis CC, Marti LC, Sempowski GD, Jeyaraj DA, Szabolcs P. Interleukin-7 permits Th1/Tc1 maturation and promotes ex vivo expansion of cord blood T cells: a critical step toward adoptive immunotherapy after cord blood transplantation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5249–5258. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Barfield R, Benaim E, Leung W, Knowles J, Lawrence D, et al. Prediction of T-cell reconstitution by assessment of T-cell receptor excision circle before allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in pediatric patients. Blood. 2005;105:886–893. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.