Abstract

Autoimmune muscle diseases (myositis) comprise a group of complex phenotypes influenced by genetic and environmental factors. To identify genetic risk factors in patients of European ancestry, we conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of the major myositis phenotypes in a total of 1710 cases, which included 705 adult dermatomyositis; 473 juvenile dermatomyositis; 532 polymyositis; and 202 adult dermatomyositis, juvenile dermatomyositis or polymyositis patients with anti-histidyl tRNA synthetase (anti-Jo-1) autoantibodies, and compared them with 4724 controls. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms showing strong associations (P < 5 × 10−8) in GWAS were identified in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region for all myositis phenotypes together, as well as for the four clinical and autoantibody phenotypes studied separately. Imputation and regression analyses found that alleles comprising the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) 8.1 ancestral haplotype (AH8.1) defined essentially all the genetic risk in the phenotypes studied. Although the HLA DRB1*03:01 allele showed slightly stronger associations with adult and juvenile dermatomyositis, and HLA B*08:01 with polymyositis and anti-Jo-1 autoantibody-positive myositis, multiple alleles of AH8.1 were required for the full risk effects. Our findings establish that alleles of the AH8.1haplotype comprise the primary genetic risk factors associated with the major myositis phenotypes in geographically diverse Caucasian populations.

Keywords: polymyositis, dermatomyositis, adult, juvenile, anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies, HLA 8.1 ancestral haplotype

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of high-throughput, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and imputation analyses have revolutionized our capacity to perform large, economically feasible, and statistically robust analyses of complex human diseases. Such large-scale GWAS have played an essential role in refining our understanding of genetic contributions to complex immune-mediated pathologies, including many human autoimmune diseases (AID) 1. To date, strong genetic associations of AID with various allelic variants of genes from the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region on chromosome 6p21.3 have been confirmed, and links to many additional non-HLA, immunoregulatory genes have been proposed2.

The myositis syndromes, or idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM), are a heterogeneous group of systemic connective tissue diseases with a presumed autoimmune etiology based on the presence of many disease-specific autoantibodies and self-directed lymphocyte responses in patients 3. Myositis patients and their close relatives are more likely to develop other autoimmune diseases, suggesting shared genetic architectures 4,5. Moreover, early candidate-gene, case-control studies of the IIM in Caucasians demonstrated strong, reproducible associations with the HLA 8.1 ancestral haplotype (AH8.1) and the DRB1 03:01 allele in particular, although, with the exception of sporadic inclusion body myositis in which recombinant mapping suggests a susceptibility region spanning 172 kb and encompassing HLA-DRB3, HLA-DRA and BTNL2 6, the independent impact of alleles comprising AH8.1 has not been determined 7,8. It was also not certain whether these genes themselves or others in linkage disequilibrium (LD) were primarily responsible for these findings 7,8. Similar genetic associations with the DRB1 03:01 allele have been reported for other AID (e.g., systemic lupus, celiac disease, dermatitis herpetiformis, type 1 diabetes and Grave’s disease), suggesting common mechanisms of immune dysregulation 9.

The AH8.1 (also known as the HLA A1-B8-DR3-DQ2 haplotype) remains an interesting and unresolved feature of our genome. It has an extremely long (> 4 megabases) conserved combination of alleles and is found in a significant fraction of the Caucasian population 10. It is usually defined by the combination of the core alleles HLA-A*01:01, -C*07:01, -B*08:01, -DRB1*03:01, -DQA1*05:01, and -DQB1*02:01, and it represents an evolutionarily highly conserved haplotype that contains hundreds of immunologically important genes. High LD within the AH8.1 region poses challenges in defining independent associations for the individual HLA variant loci using traditional molecular genetic techniques. Previous reports of associations in the HLA region were often confounded because the haplotypic complexity of AH8.1 was not taken into consideration. New genotyping methods and access to large cohorts with defined HLA genotypes allow for new approaches to resolving the AH8.1 puzzle.

The IIM include different phenotypes defined by various clinical, laboratory, autoantibody, and immunopathologic features 3,11. Among these, adult-onset dermatomyositis (DM), juvenile-onset dermatomyositis (JDM), and adult-onset polymyositis (PM) are the most prevalent and recognizable clinical phenotypes, and the anti-histidyl-tRNA synthetase autoantibodies (anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies) are the most prevalent disease-specific autoantibody phenotype in myositis 3. Because the IIM are relatively rare, with most prevalence estimates ranging from 10–20 cases per 100,000 12, progress in genetic mapping studies has been limited. As part of an international myositis genetics consortium (MYOGEN), we recently published the first GWAS in adult and juvenile DM, a clinical phenotype of the IIM readily identified by characteristic rashes and other cutaneous features. In that study, we confirmed that the MHC region contributes most of the risk for DM and identified non-MHC genetic associations that are shared among DM and other autoimmune diseases 13.

Here, we evaluated, at a genome-wide level, risk factors for the development of the most prevalent myositis phenotypes, i.e., IIM or all myositis, DM, JDM, PM, and a subset of DM, JDM or PM cases with anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies. We also sought to identify the MHC components that define the primary genetic risks for myositis and expand our analysis of HLA-associated risk factors by using GWAS single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mapping in the largest myositis population studied to date that includes the major phenotypes. Using a large, SNP-HLA allele reference panel from the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium database (n=12,893 subjects), we combined HLA allele imputation with haplotype phasing to enhance the statistical power of the IIM data analysis. Our findings provide strong evidence that, in myositis patients from the four different northern and western European populations and Americans of European descent, the primary genetic risks for IIM and its major phenotypes are the combined alleles of the AH8.1.

RESULTS

The MHC region contributes the major genetic risk for all myositis phenotypes studied

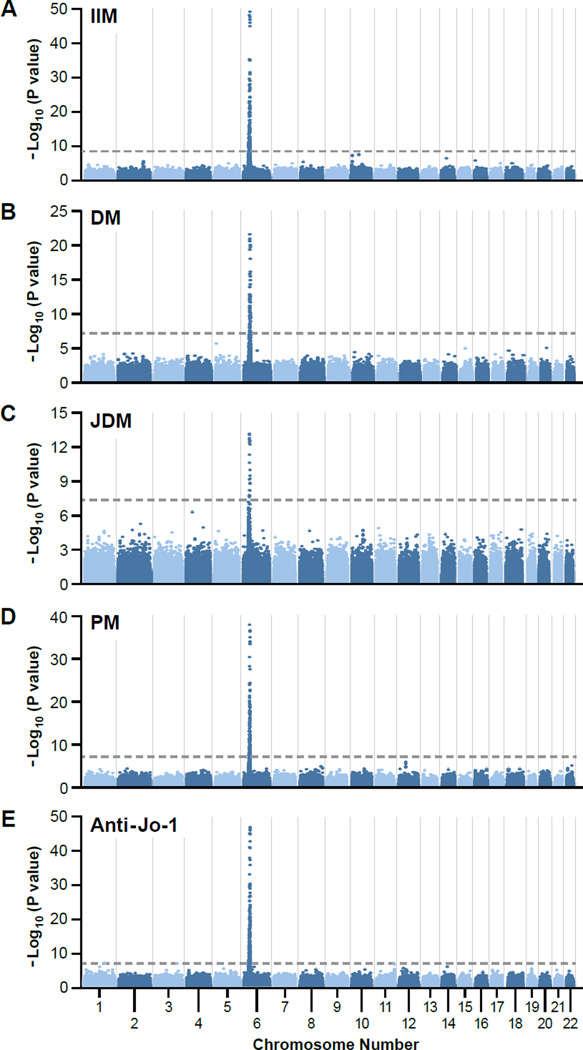

This GWAS of 1710 myositis cases and 4724 controls (Table 1) 14,15,16 showed GWAS-level significance (P< 5×10−8) at a number of genotyped SNPs across the MHC region when all myositis cases were considered together (IIM, Figure 1A).The same finding was also true for each of the four major phenotypes (DM, JDM, PM and anti-Jo-1, Figure 1B–E respectively).These findings are consistent with prior candidate gene studies that associated this region with multiple myositis phenotypes 17,18 and extend those findings to show that no other genomic region contains genes with a similar strength of association. The analysis has 90% power to detect an allele conferring an increased risk of 1.4 on the log additive scale.

Descriptive characteristics of analyzed data sets.

| Population | JDM Cases | DM Cases | PM Cases | Anti-Jo-1 Cases* |

Controls | Source | Genome-wide association study |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % Female |

N | % Female |

N | % Female |

N | % Female |

N | % Female |

Typed SNPs |

CV | λ | |||

| US | 283 | 70% | 287 | 76% | 195 | 71% | 72 | 71% | 1152 | 71% | NYCP14 | 237155 | PS | 1.176 | 1.077 |

| UK | 159 | 70% | 149 | 66% | 151 | 74% | 61 | 67% | 2415 | 48% | WTCCC215 | 236039 | none | 1.009 | 1.011 |

| Czech/Hungarian | 23 | 78% | 178 | 71% | 118 | 71% | 48 | 77% | 256 | 57% | CZ/HU | 242530 | PS | 1.016 | 1.008 |

| Swedish/Dutch | 4 | 75% | 48 | 69% | 68 | 81% | 8 | 88% | 642 | 72% | EIRA16 | 242644 | PS | 1.028 | 1.023 |

| Spanish | 4 | 50% | 43 | 81% | 0 | N/A | 13 | 77% | 259 | 66% | Spain | 242871 | PS | 1.015 | 1.01 |

| Meta-analysis | 473 | 70% | 705 | 72% | 532 | 73% | 202 | 71% | 4724 | 58% | 241502 | PS | 1.058 | 1.073 | |

Abbreviations: US, United States; UK, United Kingdom; N: number of subjects; JDM, juvenile-onset dermatomyositis; DM, adult-onset dermatomyositis; PM, polymyositis; anti-Jo-1 cases, myositis patients with autoantibodies to histidyl-tRNA synthetase; CV, Covariates; λ, Genomic inflation factor; NYCP, New York Cancer Project controls from the North American Rheumatoid Arthritis Consortium; WTCCC2, Welcome Trust Case Control Consortium2; CZ/HU, healthy Czech and Hungarian volunteers from the Institute of Rheumatology, Prague, Czech Republic or the University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary; EIRA, Epidemiological Investigation of risk factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis; Spain, blood bank volunteers in Granada, Spain; PS, Population on Structure.

Anti-Jo-1 cases are those JDM, DM and PM cases from prior columns who have anti-histidyl-tRNA synthetase autoantibodies

1.037 without MHC region

Figure 1.

Results of genome-wide association analyses of major myositis phenotypes: (A) all myositis (IIM, n=1710); (B) adult dermatomyositis (DM, n=705); (C) juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM, n=473); (D) polymyositis (PM, n= 532); and (E) anti-histidyl-tRNA synthetase autoantibodies (Anti-Jo-1, n=202) – all plotted on a genomic scale (Manhattan plot) showing P values for successfully genotyped single nucleotide polymorphisms. The dotted line represents the genome-wide level of significance (P = 5 × 10−8).

GWAS identified alleles of the AH8.1 as the major genetic risk factors for all myositis cases combined

We next determined the genes in the MHC region that contributed the major genetic risks noted above. Imputation analyses of the loci that had HLA typing data available (Table S1) showed excellent imputation accuracy (imputation R2>0.8) for HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, -DQA1, -DQB1, and -DPB1 alleles (supplemental methods). Association analyses of the IIM (i.e., all myositis cases combined) identified the strongest associations with AH8.1 alleles, notably HLA-DRB1*03 (P=9.7 × 10−47, OR=2.25), HLA-DRB1*03:01 (P=7.9 × 10−46, OR=2.23), HLA-DQB1*02:01 (P=7.7 × 10−45, OR=2.18), and HLA-B*08:01 (P=7.7× 10−44, OR=2.21) (Table 2). The strength of associations did not vary substantially among the geographic groups for these loci. However, there was evidence of heterogeneity at the HLA-C*07:01 and HLA-DQA1*05:01 loci in the total population (Table 2). The Swedish/Dutch (SWNL, OR=2.64) and United Kingdom (UK, OR=1.92) populations had higher risk values compared with other groups for HLA-C*07:01, and similarly for HLA-DQA1*05:01 (OR=2.02 and OR=1.66, respectively) , suggesting a North-South gradient in risk for these variants (Table S2).

Table 2.

Analyses of imputed HLA types from all myositis GWAS data - 1710 IIM cases compared to 4724, controls

| HLA Alleles | BP | Meta Analysis | HLA Allele Frequencies | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | OR(R) | P | P(R) | Q | I | US Cases |

US Controls |

UK Cases |

UK Controls |

CZHU Cases |

CZHU Controls |

SP Cases |

SP Controls |

SWNL Cases |

SWNL Controls |

||

| DRB1*03 | 32552080 | 2.25 | 2.26 | 9.69×10−47 | 2.81×10−42 | 0.371 | 6 | 0.215 | 0.124 | 0.263 | 0.142 | 0.218 | 0.106 | 0.234 | 0.126 | 0.313 | 0.143 |

| DRB1*03:01 | 32552080 | 2.23 | 2.25 | 7.94×10−46 | 5.98×10−38 | 0.337 | 12 | 0.214 | 0.125 | 0.263 | 0.142 | 0.218 | 0.106 | 0.223 | 0.124 | 0.313 | 0.143 |

| DQB1*02:01 | 32630854 | 2.18 | 2.18 | 7.68×10−45 | 2.71×10−44 | 0.402 | 0.8 | 0.214 | 0.125 | 0.268 | 0.146 | 0.221 | 0.106 | 0.223 | 0.127 | 0.308 | 0.143 |

| B*08:01 | 31323319 | 2.21 | 2.21 | 7.74×10−44 | 7.74×10−44 | 0.499 | 0 | 0.211 | 0.119 | 0.253 | 0.141 | 0.219 | 0.107 | 0.128 | 0.064 | 0.296 | 0.133 |

| B*08 | 31323319 | 2.20 | 2.20 | 1.82×10−43 | 1.82×10−43 | 0.468 | 0 | 0.208 | 0.119 | 0.253 | 0.140 | 0.219 | 0.107 | 0.128 | 0.064 | 0.296 | 0.133 |

| C*07:01 | 31238219 | 1.77 | 1.84 | 8.79×10−28 | 7.10×10−10 | 0.026 | 64 | 0.242 | 0.180 | 0.282 | 0.174 | 0.262 | 0.178 | 0.202 | 0.133 | 0.329 | 0.162 |

| DPB1*01:01 | 33050588 | 2.07 | 2.07 | 4.03×10−21 | 4.03×10−21 | 0.811 | 0 | 0.092 | 0.051 | 0.117 | 0.058 | 0.092 | 0.049 | 0.085 | 0.041 | 0.138 | 0.060 |

| DQA1*05:01 | 32608306 | 1.45 | 1.43 | 1.45×10−15 | 2.56×10−4 | 0.007 | 72 | 0.308 | 0.257 | 0.351 | 0.246 | 0.370 | 0.324 | 0.298 | 0.307 | 0.367 | 0.229 |

| DPA1*01:03 | 33036900 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 9.11×10−13 | 9.11×10−13 | 0.870 | 0 | 0.234 | 0.180 | 0.243 | 0.183 | 0.230 | 0.166 | 0.287 | 0.209 | 0.229 | 0.152 |

| DPA1*02:01 | 33036900 | 1.48 | 1.48 | 2.02×10−12 | 2.02×10−12 | 0.591 | 0 | 0.190 | 0.142 | 0.194 | 0.145 | 0.198 | 0.129 | 0.245 | 0.180 | 0.196 | 0.111 |

| DRB1*15 | 32552080 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 4.53×10−9 | 4.53×10−9 | 0.447 | 0 | 0.096 | 0.153 | 0.107 | 0.136 | 0.083 | 0.117 | 0.075 | 0.102 | 0.117 | 0.149 |

| DRB1*15:01 | 32552080 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 5.96×10−9 | 5.96×10−9 | 0.826 | 0 | 0.090 | 0.139 | 0.096 | 0.131 | 0.075 | 0.104 | 0.064 | 0.089 | 0.113 | 0.146 |

Abbreviations: BP, base pair position of the center of the gene; OR, odds ratio; R, random effects; P, P-value; Q, Q-statistic measure of heterogeneity; I, percent variability among studies; US, United States; UK, United Kingdom; CZHU, Czech/Hungarian; SP, Spanish; SWNL, Swedish/Dutch.

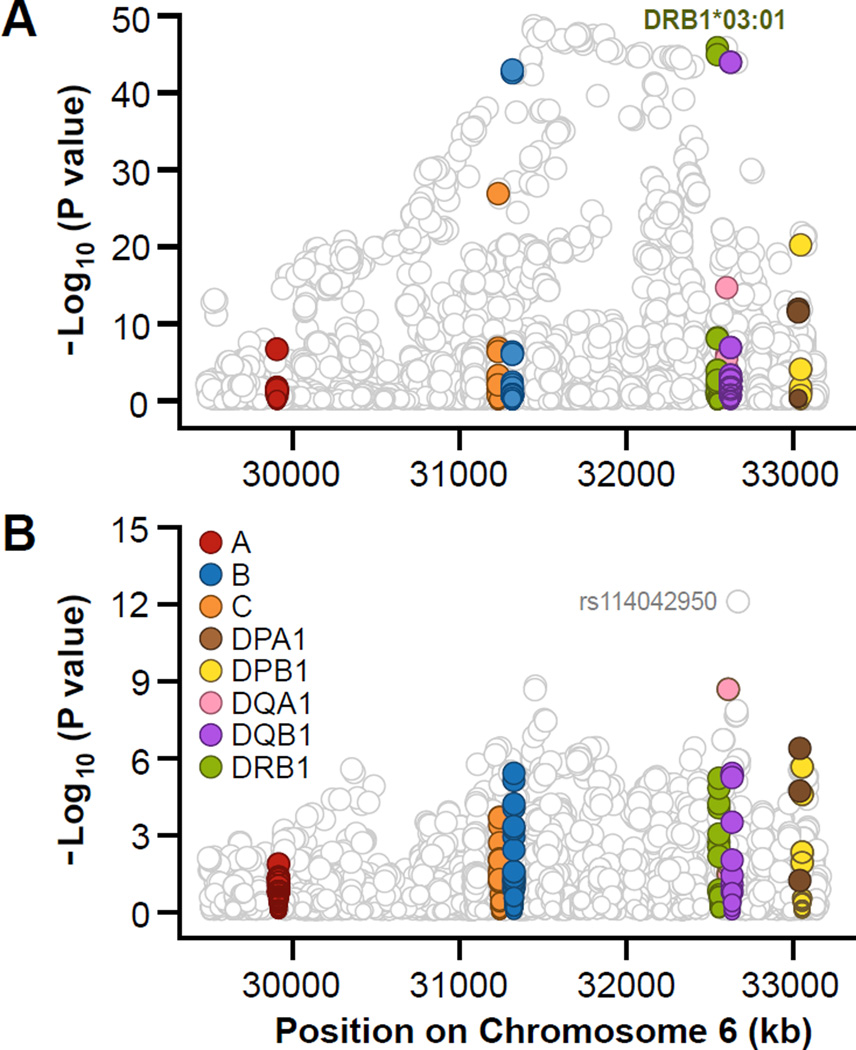

An analysis of SNP and HLA associations conditioned on the HLA-DRB1*03:01 allele resulted in the decrease of the strength of the associations of most SNPs but several SNPs still reached the genome-wide significant level. There was a residual effect for SNPs rs114042950 (and rs114388793, which is in strong LD with rs114042950) (OR=1.51, P=3.9 × 10−11), with minor allele G frequencies ranging from 0.092 to 0.19 (Figure 2 and Table S3) that are in moderate LD with DQB1*03:02 (R2=0.65). However the random effect P value in meta-analysis was not significant indicating the fixed effect P value was significant due to heterogeneity thus consistent with this finding being a false-positive. The genome-wide significant SNPs and HLA variants before and after conditioning (Table S3) on the most significant HLA variant DRB1*03:01 for IIM in the meta-analysis of five geographical groups, are also shown in Figure 2 Panels A and B, respectively. Most of these SNPs are not associated with known functions but the closest genes and locations relative to these SNPs are listed in Table S3. Other residual effects came from SNPs rs114771815 (P=9.0 × 10−11, OR=1.70), rs116662199 (P=1.7 × 10−10, OR=1.69), rs114050967 (P=5.6 × 10−10, OR=1.71), and several other SNPs (Table S3).

Figure 2.

Association plots for the analyzed variants and HLA gene variants showing regional distributions for all SNPs and HLA alleles in the MHC region for all 1710 myositis cases compared to 4724 controls: A) shows unconditioned data; and B) shows data conditioned on DRB1*03:01.

To assess whether SNPs might be tagging an extended haplotype of HLA alleles rather than reflecting the independent effect of the SNP on myositis risk, we conducted a haplotype-based analysis in which we tested at each point whether adding SNPs or HLA alleles yielded the most parsimonious haplotype-based model to explain variability in risk. The individual test of significance for effect from DRB1*03:01 yielded a P-value of 8.41 × 10−42. Further testing for the haplotype of DRB1*03:01 with DQB1*02:01 led to a P-value of 3.4 × 10−51 (), whereas the combination of AH8.1 alleles DRB1*03:01, B*08:01, and DQB1*02:01 led to a P-value of 2.5 × 10−61(), giving the best fit to the data when only HLA types were included in the analysis (Table 3). The haplotype that included alleles at these three loci fit the data better than a haplotype with two loci (P=3.4 × 10−13, ) (Table 3). The presence of a haplotype with all three risk alleles occurred in 18.2% of cases compared with 9.7% of controls (P=3.4 × 10−40), whereas the presence of a haplotype without all three risk alleles occurred in 71.5% of cases compared with 83.1% of controls (P=1.46 × 10−47). A prior study 19 found that the DPB1*01:01 allele subdivided assocations of the 8.1 haplotype according to auto anti-Jo-1 status but we did not see an overall decrease in the significance when adding the DPB1*01:01 to haplotype based analysis. Although the alleles of rs114771815 were more significant than any individual HLA allele, adding this SNP to the extended AH8.1 haplotype led to a less significant model suggesting that variability in risk for myositis is most parsimonious with effects from classic HLA alleles alone.

Table 3.

Haplotype analysis of all 1710 myositis cases compared to 4724 controls showing that multiple members of the 8.1 haplotype contribute to overall genetic risk.

| Haplotype | Frequency | CHISQ | DF | P-value | HLA Alleles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | |||||

| 2 | 0.235 | 0.135 | 184 | 1 | 8.41×10−42 | DRB1*03:01 |

| 2 | 0.237 | 0.138 | 180 | 1 | 5.14×10−41 | DQB1*02:01 |

| 2 | 0.227 | 0.128 | 188 | 1 | 8.70×10−43 | B*08:01 |

| 2 | 0.262 | 0.172 | 129 | 1 | 5.76×10−30 | C*07:01 |

| 2 | 0.102 | 0.055 | 85 | 1 | 2.75×10−20 | DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS* | — | — | 237 | 3 | 3.43×10−51 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 302 | 7 | 2.54×10−61 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 323 | 15 | 9.71×10−60 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 339 | 28 | 4.79×10−55 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ C*07:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

Abbreviations: CHISQ, chi-square; DF, degrees of freedom; —, not available

The omnibus test evaluates the joint association of all haplotypes with variability in disease risk

We determined the LD and gene-gene correlations and interactions among all SNPs and HLA alleles. Among genome-wide significant HLA alleles, the following HLA variant pairs were in moderate to strong LD: HLA-DRB1*03:01 and -DQB1*02:01 (R2=0.93); HLA-DRB1*15:01 and DQB1*06:02 (R2=0.76); HLA-C*07:01 and -B*08:01 (R2=0.65); and HLA-DRB1*03:01 and HLA-B*08:01 (R2=0.52). We also observed a surprising correlation between DPA1*01:03 and DPA1*02:01 (R2 =0.76). This region contains multiple insertions and duplications with, for example 16 different copy number variants influencing the DPA1 gene as noted by Pinto et al. 20.

Because prior studies suggested a possible role for the AH8.1-associated tumor necrosis factor 2 (TNF2) allele of the TNFα gene in myositis 21, we assessed the related SNP (rs1800629) for associations with myositis Before conditioning on HLA alleles, the association of rs1800629 with risk for myositis yielded an OR of 1.96 (P=6.4 × 10−34) but after conditioning on DRB1*03:01, the residual association yielded an OR of 1.43 (P=1.1 × 10−7) and the association was further reduced to an OR of 1.19 (P=0.051) after conditioning on DRB1*03:01, DPB1*02:01 and B*08:01. No significant (P<1 × 10−5) gene-gene interactions for risk of myositis were identified (data not shown).

GWAS identified alleles of the AH8.1 as the major genetic risk factors for the most common individual myositis phenotypes

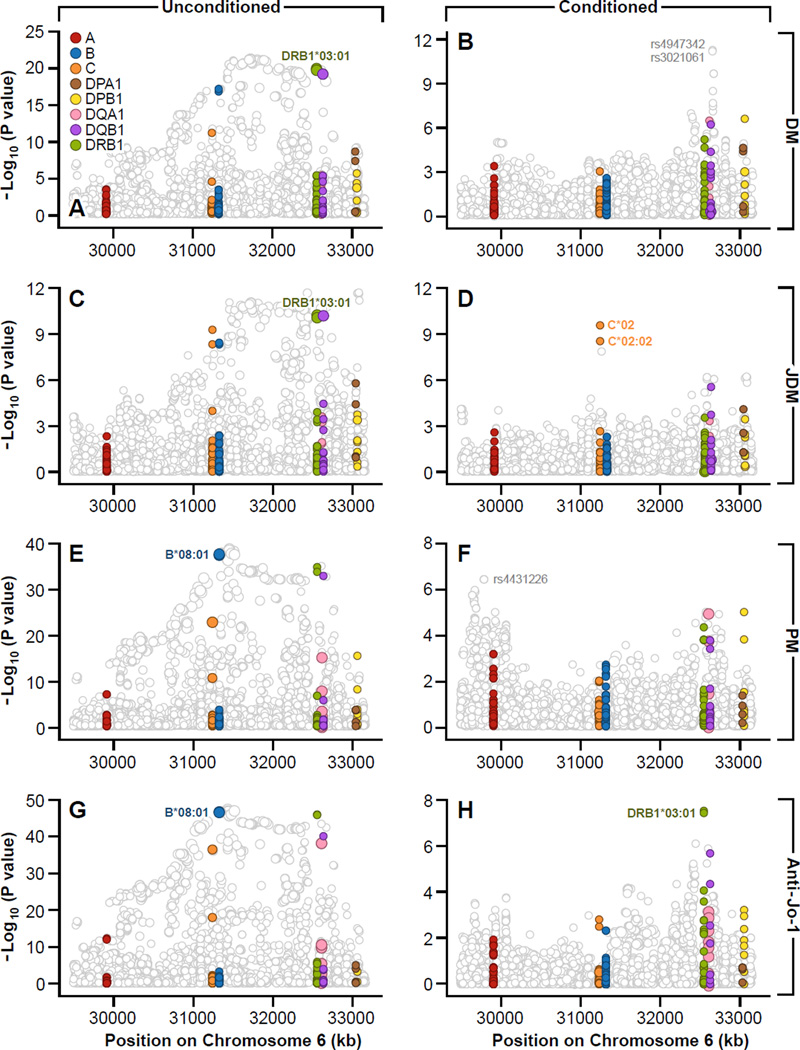

Similar analyses were performed for each of the major myositis phenotypes (DM, JDM, PM, and anti-Jo-1 autoantibody–positive myositis cases), and similar results were obtained (Figures 1 and 3). Remarkably, for these phenotypes the highest genetic risks in the MHC were seen in the smallest population, myositis patients with anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies (Figure 1), supporting the concept that myositis autoantibody phenotypes are more genetically homogeneous, as they are more clinically homogeneous, than clinically defined phenotypes 22–25. For each phenotype, however, virtually all of the significant genome-wide SNPs were eliminated after conditioning on AH8.1 alleles, with a few exceptions. For example: in DM, the most significant residual SNPs were rs4947342 and rs3021061, which had an OR of 1.61 (P=1.5 × 10−9); in JDM, HLA-C*02 (OR=2.55, P=3.0 × 10−11) and HLA-C*02:02 (OR=2.47, P=3.2 ×10−10) remained significant after conditioning on other alleles of the AH8.1; and in PM and in anti-Jo-1 autoantibody–positive cases; no other SNPs remained significant (Figure 3). Of interest, imputation analyses revealed that HLA-DRB1*03:01 was the strongest genetic risk factor for DM and JDM and that HLA-B*08:01 was the strongest genetic risk factor for PM and myositis with anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies. In all the myositis phenotypes, however, the highest genetic risk was seen when alleles at multiple loci of the AH8.1 were considered together (Tables 4–7). As was the case for all myositis phenotypes combined, our results largely eliminate effects of the -308 TNF2 allele from playing a significant role in any one of the phenotypes studied, after allowing for HLA alleles (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Association plots for the analyzed SNP and HLA gene variants showing regional distributions in the MHC region for dermatomyositis (A, B), juvenile dermatomyositis (C, D), polymyositis (E,F) and anti-Jo-1 autoantibody (G, H) cases, unconditioned and conditioned on the most significant HLA 8.1 AH alleles, respectively. The most significant HLA 8.1 AH alleles are labeled in the unconditioned plots.

Table 4.

Haplotype analysis of 705 adult dermatomyositis cases compared to 4724 controls.

| Haplotype | Frequency | CHISQ | DF | P-value | HLA Alleles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | |||||

| 2 | 0.220 | 0.135 | 70 | 1 | 5.22×10−17 | DRB1*03:01 |

| 2 | 0.221 | 0.138 | 68 | 1 | 1.55×10−16 | DQB1*02:01 |

| 2 | 0.205 | 0.128 | 61 | 1 | 7.33×10−15 | B*08:01 |

| 2 | 0.250 | 0.172 | 51 | 1 | 9.32×10−13 | C*07:01 |

| 2 | 0.094 | 0.055 | 32 | 1 | 1.64×10−08 | DPB1*01:01 |

| 2 | 0.206 | 0.141 | 41 | 1 | 1.35×10−10 | DPA1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS* | — | — | 92 | 3 | 7.83×10−20 | DRB1*03:01_DQB1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 77 | 3 | 1.63×10−16 | DRB1*03:01_B*08:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 77 | 3 | 1.28×10−16 | DRB1*03:01_DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 129 | 7 | 1.16×10−24 | DRB1*03:01_DQB1*02:01_B*08:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 157 | 15 | 8.57×10−26 | DRB1*03:01_DQB1*02:01_B*08:01_DPA1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 100 | 7 | 1.23×10−18 | DRB1*03:01_DQB1*02:01_DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 122 | 13 | 8.50×10−20 | DRB1*03:01_DQB1*02:01_DPB1*01:01_DPA1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 94 | 7 | 2.32×10−17 | DRB1*03:01_B*08:01_DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 117 | 15 | 6.36×10−18 | DRB1*03:01_B*08:01_DPB1*01:01_DPA1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 147 | 15 | 9.84×10−24 | DRB1*03:01_DQB1*02:01_B*08:01_DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 173 | 27 | 3.07×10−23 | DRB1*03:01_DQB1*02:01_B*08:01_DPB1*01:01_DPA1*02:01 |

Abbreviations: CHISQ, chi-square; DF, degrees of freedom; —, not available

The omnibus test evaluates the joint association of all haplotypes with variability in disease risk

Table 7.

Haplotype analysis of 202 myositis cases with anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies compared to 4724 controls.

| Haplotype | Frequency | CHISQ | DF | P-value | HLA Alleles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | |||||

| 2 | 0.418 | 0.128 | 270 | 1 | 9.72×10−61 | B*08:01 |

| 2 | 0.426 | 0.135 | 260 | 1 | 1.44×10−58 | DRB1*03:01 |

| 2 | 0.408 | 0.138 | 225 | 1 | 8.59×10−51 | DQB1*02:01 |

| 2 | 0.443 | 0.172 | 191 | 1 | 1.99×10−43 | C*07:01 |

| 2 | 0.156 | 0.055 | 70 | 1 | 5.10×10−17 | DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS* | — | — | 306 | 3 | 4.20×10−66 | B*08:01 _ DQB1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 316 | 3 | 3.50×10−68 | B*08:01 _ DRB1*03:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 401 | 7 | 1.20×10−82 | B*08:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ DRB1*03:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 407 | 13 | 6.85×10−79 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 415 | 24 | 5.67×10−73 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ C*07:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

Abbreviations: CHISQ, chi-square; DF, degrees of freedom; —, not available

The omnibus test evaluates the joint association of all haplotypes with variability in disease risk

Logistic association tests were used to assess females (n=1232) and males (n=478) and did not show any significant SNP or HLA allele frequency differences, which suggests that it is unlikely there are significant differences in genetic risk factors between female and male myositis patients. Similarly, results did not show significant differences between anti-Jo-1-positive DM (n=94) and anti-Jo-1-positive PM (n=108) cases (data not shown). We also did not detect any significant differences between known anti-Jo-1-negative DM (n=132) and anti-Jo-1-negative PM (n=81) cases. Assessments of gene-gene interactions for all alleles associated with all the myositis phenotypes showed no evidence of significant interactions (data not shown). We also applied two different machine learning tools – Random Forests and Classification Trees – to check for additional genotypic combinations among HLA alleles that might better model risk than analysis of alleles and extended haplotypes but these analyses did not extend our existing findings. Finally, we applied Fastphase26 to exhaustively search for any additional haplotypic combinations that significantly improved our risk assessment beyond that of extended haplotype analyses here presented but did not identify any additional associations.

We further evaluated risk from homozygous and heterozygous risk alleles by disease grouping. In all phenotype groups, the results showed that there was no significant difference between the dominant and general models and that the recessive model was rejected (Table S4). The additive model was rejected for all phenotype groups except JDM. For all phenotype groups combined, the dominant model gave the best fit to the data. Odds ratios show striking effects from some HLA alleles on risk for development of myositis (Table S5). For HLA DRB1*03:01,the risks are 2.63 for IIM, 2.41 for DM and 2.61 for JDM, while the risk associated with HLA B*08:01 are 3.66 for PM and 11.10 for anti-Jo-1 positive myositis.

DISCUSSION

These findings, which to our knowledge include the first GWAS of PM and myositis patients with anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies, are consistent with previous targeted studies suggesting that the MHC is an important genetic region associated with myositis overall and with many individual myositis phenotypes 17,18. However, we have extended prior studies via imputation analyses and statistical regression of the HLA data to show that gene variants within AH8.1 explain nearly all the genetic risk in the major myositis phenotypes in Caucasians. Although the strongest individual allelic associations are HLA-DRB1*03:01 for DM and JDM and HLA-B*08:01 for PM and anti-Jo-1 autoantibody–positive myositis, it is clear that multiple alleles of AH8.1 contribute to the risk for myositis. While specific HLA alleles on the AH8.1 were most strongly associated with myositis, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that they might also be tagging additional variation on the haplotype that cannot be observed except via extensive resequencing studies.

The AH8.1, traditionally defined by HLA-A1, -B8, -Cw7, -DRB1*03:01, -DQA1*05:01, and -DQB1*02:01, is, at 4.7 million nucleotides, the second longest haplotype identified within the human genome and is the haplotype most commonly associated with immune-mediated diseases 27. That it is the most common haplotype in Caucasian populations also suggests that it might have been advantageous in past environments. It is also remarkably stable, being resistant to recombination, and appears to have been positively selected over millennia 28. Although several AH8.1-associated immune-mediated diseases are more prevalent in women than men (e.g., myositis and systemic lupus erythematosus), AH8.1 is also prevalent in elderly men 27. Therefore, its persistence in the population may be due to the advantages that AH8.1 exerts on males, which outweigh the disadvantages conferred in females. Another form of myositis, which is uniquely seen more commonly in men than women, is sporadic inclusion body myositis. It is interesting that for this disease, recombination studies suggest that a common AH8.1-specific susceptibility region, spanning 172 kb and encompassing three genes--HLA-DRB3, HLA-DRA and BTNL2–is likely important in pathogenesis6.

Our analyses suggest that TNF alleles are not playing a significant role in influencing risk independent of the 8.1 haplotype. 29 We cannot exclude however the possibility that other alleles associated with AH8.1 may contribute to disease risk beyond that conferred by the classical HLA alleles identified in this study as the strongest genetic risk factors.

While the IIM, like other autoimmune diseases, are thought to develop as a consequence of chronic inflammation resulting from environmental exposures in genetically susceptible individuals, few examples of such gene-environment interactions have been reported 30,31, and none have explained the strong association between AH8.1 and the different myositis phenotypes. The facts that HLA genes: (a) are important in responses to many infectious and noninfectious environmental exposures 32; and (b) determine one’s capacity to produce antibodies including many autoantibodies 33, could explain why specific combinations of HLA alleles are important to the pathogenesis of myositis. The mechanisms underlying HLA associations in AID, however, are not clearly understood.

A traditional view suggests that there is a breakdown in immunological tolerance to self-antigens through aberrant HLA presentation of self-peptides or homologous foreign peptides to autoreactive T lymphocytes. Therefore, it is possible that certain MHC alleles determine the targeting of particular autoantigens, resulting in the observed disease-specific associations. Other explanations, however, have been suggested, including: (a) that specific HLA alleles result in altered thymic selection in which high-affinity self-reactive T cells escape negative selection; or (b) that genetic polymorphisms play a significant role in determining the transcriptional response to differing innate immune stimuli in a context-specific manner .

AH8.1 also plays a role in interactions with and functional alterations of many immune functions that could contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases 27. For example, individuals with AH8.1 tend to have higher levels of autoantibodies, peripherally activated T cells, circulating immune complexes, and lymphocyte apoptosis, and lower levels of blood lymphocytes, natural killer cell activity, and antibody responses to Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B virus, and influenza virus 27,34,35. Furthermore, the microbiome has been shown to influence both physiology and disease risk because of the role it plays in modulating immune responses. Intestinal microbiota have been found to be influenced by specific HLA alleles that are also risk factors for certain autoimmune diseases, which might provide another possible explanation for HLA associations with IIM 36,37. Given our limited understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms in myositis as well as the specific functions of allelic variants of genes associated with autoimmunity, additional studies are needed to understand the functional implications of our data.

The limitations of this study include its moderate statistical power, despite being the largest study ever conducted on this rare disease spectrum, and heterogeneity in the clinical groups resulting from multiple autoantibody phenotypes for which genetic associations sometimes vary from the clinical phenotypes 18. These issues should all be addressed in larger, confirmatory studies.

Taken together, our findings suggest that AH8.1 and its component HLA alleles impart the major genetic risk for myositis and its main phenotypes. An enhanced appreciation for the role of these HLA variants in the autoimmune pathogenesis of myositis, as well as mechanistic studies and identification and confirmation of additional genetic and environmental risk factors, should ultimately enable the development of molecular profiles that could allow for novel diagnostics and therapeutics.

MATERIALS, SUBJECTS and METHODS

Study populations

Investigators in the United States, United Kingdom, Czeck Republic, Hungary, Sweden, the Netherlands and Spain with collections of DNA samples from cohorts of myositis patients collected from several different studies formed an international collaboration called the Myositis Genetics Consortium (MYOGEN) with the goal of identifying genetic factors associated with myositis. The general approach was to include subjects who had given consent for studies that had been reviewed by appropriate IRB boards using predefined criteria the DM subjects in our prior publication 13. Here we extended our study to include the major clinical phenotypes, adult and juvenile DM and PM, as well as the most common serologic phenotype, namely, that of anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies 11. The criteria for inclusion of PM cases were predetermined to be probable or definite PM as defined by proximal weakness, myopathy on electromyography, muscle biopsy consistent with IIM or elevated serum muscle enzymes, and the criteria for DM were the same plus the presence of Gottron’s papules/sign or heliotrope rash, with exclusion of other causes of muscle disease in all cases, per Bohan and Peter criteria 38. The probable or definite DM criteria, but with age at onset of less than 18 years defined JDM. Anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies were defined by reactivity to histidyl-tRNA synthetase, as determined by validated immunoprecipitation methods 24,39. In order to optimize case-control matching, we utilized separate control groups for each geographic cohort 13. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and this investigation has been approved by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/ National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Institutional Review Board (protocol 94-E-0165). The subjects included in this study are detailed in Table 1.

Genotyping and quality control

Genotyping of cases was carried out using various Illumina GWAS arrays at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York, USA, as reported previously 13. Only SNPs that were present on all platforms were evaluated. SNPs that yielded P > 0.001 in association tests comparing only cases genotyped on different chips within each geographic group were dropped in the final results (n=1372 in GWAS) to eliminate any variation in genotyping quality among arrays.

All data underwent quality control before merging and final statistical analyses. The following data were excluded: SNPs with a call rate of less than 95% on any platform, individuals with more than 10% missing rates in genotypes, and SNPs of minor allele frequency ≤0.01 or Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in controls with a P-value ≤ 10−5. Merged data were separated into five groups according to geographic region (US, UK, Swedish/Dutch, Czech/Hungarian, and Spanish). Relatedness was checked by estimating the identity-by-descent coefficient in PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/) 40. Principal components analysis was performed separately using PLINK on each of the major groups of study participants listed in Table 1 as previously reported13. We removed any outliers more than 10−5 standard deviations from the centroid.

HLA alleles and imputation

HLA data, provided by Dr. Steve Rich from T1DGC in 2012, were used as the reference panel for the imputation of complete or additional HLA alleles and SNPs in the MHC region. The T1DGC HLA data contain 7135 SNPs in the HLA region (with 610 duplicated positions of same or opposite allele reading) and 408 HLA alleles in 4-digit coding (i.e., higher resolution) from 8 HLA genes (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DPA1, and HLA-DPB1) typed on 12,893 people from 3329 T1DGC families. In order to impute the HLA alleles with 2-digit coding (i.e., lower resolution) for HLA-A, -C, -B, and -DRB1 in the genotyped myositis cases and controls, we collapsed the 4-digit coding of T1DGC HLA data for these 4 genes to 82 alleles with 2-digit coding and included them in the reference panel for imputation.

Briefly, the SNP genotyping data of T1DGC were lifted to build 37 positions by using UCSC’s liftOver tool based on dbSNP134. Then the SNP genotyping data were aligned to the forward strand by checking them against 1000 Genomes Phase I V2 Northern Europeans from Utah (CEU) data using Beagle’s utility programs (http://www.stat.auckland.ac.nz/~browning/beagle/strand_switching/strand_switching.html; http://faculty.washington.edu/browning/beagle_utilities/utilities.html) and flipping to forward if necessary. A total of 6362 unique SNPs in the T1GDC data were successfully aligned and then merged with 408 4-digit HLA alleles and 82 2-digit HLA alleles coded as diallelic markers, as follows: 2 2 = two copies of the specific allele; 1 2 = one copy of the specific allele, 1 copy of another HLA allele; 1 1 = two copies of other HLA alleles; 0 0 = missing all HLA alleles; 0 2 = missing one HLA allele and 1 copy of a specific allele; and 0 1 = missing one HLA allele and 1 copy of another HLA allele. The SNPs were then assigned the physical positions around the center position of each HLA gene to standardize alignment. Lastly, we used 6852 markers (SNPs or HLA alleles) of two alleles from 12,983 people as reference data in HLA imputation 41–43. After imputation and filtering to remove SNPs with minor allele frequencies of <0.05 and imputation accuracy >80%, 231 HLA alleles were available for analysis. Detailed information about HLA imputations are described in the supplemental methods section.

Statistical analyses

For genomic analyses, we required genome-wide significance levels (5×10−8) for consideration of allelic effects while allowing for genome-wide correction for multiple tests. Power was set to detect an allelic relative risk ratio of at least 1.3 per allele using a log additive model and assuming the prevalence of myositis is 14 per million44. Power was calculated using the genetic power calculator45. Subtype analyses for which specific hypotheses were considered, we required the traditional p-value of 0.05 for significance. All p-values derive from chi-square tests which are evaluated two-sided hypotheses.

Meta-analyses were conducted using PLINK, which performs fixed-effects analysis using inverse variance weighting to combine the studies 46. We also present results from a meta-analysis calculated using a random effects model 47, which adjusts for the heterogeneity of effects among studies, when that is present. Also presented are Cochrane’s Q statistic as a measure of heterogeneity among studies and the I2 index, which indicates the percent of variation among studies (ranging from no heterogeneity to 100%).

We applied meta-analysis to the logistic regression tests of the five geographical studies. The number of SNP signals were dramatically reduced after conditioning on the most significant HLA allele (HLA-DRB1*03:01 for all cases, adult DM, and JDM; HLA-B*08:01 for PM and anti-Jo-1-positive myositis). We further conditioned on the most significant SNP signals and/or HLA alleles together with the most significant HLA allele until there were no more signals of genome-wide significance. The logistic regression tests with adjustment of covariates and meta-analyses were performed using PLINK.

We performed haplotype analyses that included the most significantly associated HLA alleles. To evaluate effects of haplotypes, we performed an Omnibus test implemented in PLINK that compares the joint distribution in cases of haplotypes to the joint distribution in controls and performs a χ2 test with degrees of freedom one less than the number of haplotypes fitted. In these analyses, we added SNPs if the omnibus test for haplotypes significantly improved the fit of a model compared to a model without a specific variant, starting with analysis of HLA-DRB1*03:01, then sequentially adding HLA-B*08:01 and HLA-DQB1*02:01, as these markers improved the omnibus fit when comparing the difference in chi-square tests as haplotypes were extended.

In addition, we determined whether there were significant differences between female and male cases, anti-Jo-1-positive DM and anti-Jo-1-positive PM cases, and anti-Jo-1-negative DM and anti-Jo-1-negative PM cases. Assessments of gene-gene interactions for all alleles associated with myositis in the whole group were performed using PLINK.

To identify the relationship between genotypes and risk, we applied a Mantel-Haenszel test in which the strata were formed by the five different population groups. Odds ratios were calculated treating the homozygous non-risk genotype as referent and comparing risk for heterozygous and homozygous carriers of risk alleles. To identify the best fitting genetic model, we used unconditional logistic regression, treating the population sites as categorical covariates and contrasted a general model in which additive and dominant effects were jointly modeled (with two degrees of freedom for genotype) to either additive models with the risk increasing log linearly with number of risk alleles, dominant (in which risk was identical for heterozygous and homozygous carriers) or recessive models (in which risk was only increased for homozygous carriers). Tests were constructed by comparing the log likelihood ratio for the general model to the three restricted models, forming a test that was distributed as a chi-squared variate with one degree of freedom.

Supplementary Material

Table 5.

Haplotype analysis of 473 juvenile dermatomyositis cases compared to 4724 controls.*

| Haplotype | Frequency | CHISQ | DF | P-value | HLA Alleles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | |||||

| 2 | 0.212 | 0.135 | 41 | 1 | 1.35×10−10 | DRB1*03:01 |

| 2 | 0.215 | 0.138 | 42 | 1 | 1.06×10−10 | DQB1*02:01 |

| 2 | 0.198 | 0.128 | 36 | 1 | 2.11×10−09 | B*08:01 |

| 2 | 0.230 | 0.172 | 20 | 1 | 8.04×10−06 | C*07:01 |

| 2 | 0.892 | 0.945 | 42 | 1 | 7.57×10−11 | DPB1*01:01 |

| 2 | 0.081 | 0.041 | 31 | 1 | 2.83×10−08 | C*02:02 |

| OMNIBUS* | — | — | 122 | 3 | 3.37×10−26 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 48 | 3 | 1.99×10−10 | DRB1*03:01 _ B*08:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 71 | 3 | 3.13×10−15 | DRB1*03:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 77 | 3 | 1.54×10−16 | DRB1*03:01 _ C*02:02 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 171 | 7 | 1.50×10−33 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 213 | 13 | 3.22×10−38 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ C*02:02 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 150 | 7 | 4.25×10−29 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 199 | 14 | 8.46×10−35 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ DPB1*01:01 _ C*02:02 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 80 | 7 | 1.34×10−14 | DRB1*03:01 _ B*08:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 126 | 13 | 1.21×10−20 | DRB1*03:01 _ B*08:01 _ DPB1*01:01 _ C*02:02 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 204 | 14 | 1.02×10−35 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 255 | 24 | 1.94×10−40 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ DPB1*01:01 _ C*02:02 |

Abbreviations: CHISQ, chi-square; DF, degrees of freedom; —, not available

The omnibus test evaluates the joint association of all haplotypes with variability in disease risk

Table 6.

Haplotype analysis of 532 polymyositis cases compared to 4465 controls.

| Haplotype | Frequency | CHISQ | DF | P-value | HLA Alleles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | |||||

| 2 | 0.283 | 0.132 | 172 | 1 | 3.43×10−39 | B*08:01 |

| 2 | 0.275 | 0.136 | 144 | 1 | 3.00×10−33 | DRB1*03:01 |

| 2 | 0.276 | 0.138 | 140 | 1 | 2.22×10−32 | DQB1*02:01 |

| 2 | 0.305 | 0.174 | 106 | 1 | 6.30×10−25 | C*07:01 |

| 2 | 0.106 | 0.056 | 41 | 1 | 1.25×10−10 | DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS* | — | — | 186 | 3 | 3.60×10−40 | B*08:01 _ DQB1*02:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 184 | 3 | 1.35×10−39 | B*08:01 _ DRB1*03:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 224 | 7 | 8.01×10−45 | B*08:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ DRB1*03:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 230 | 13 | 8.33×10−42 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

| OMNIBUS | — | — | 249 | 24 | 2.67×10−39 | DRB1*03:01 _ DQB1*02:01 _ B*08:01 _ C*07:01 _ DPB1*01:01 |

Abbreviations: CHISQ, chi-square; DF, degrees of freedom; —, not available

The omnibus test evaluates the joint association of all haplotypes with variability in disease risk

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by: the Intramural Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS Z01ES101074); European Community’s FP6, AutoCure LSHB CT-2006-018661; Myositis UK; Arthritis Research UK (18474 and 20164); The Cure JM Foundation; the European Science Foundation in the framework of the Research Networking Programme European Myositis Network (EuMyoNet); Association Francaise Contre Les Myopathies (AFM), the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at ICH/GOSH; the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit; the Wellcome Trust; Action Medical UK; Great Ormond Street Children’s Charity; the National Institute for Health Research Translational Research Collaboration on rare diseases; and the Swedish Research Council. The Czech cohort was partially supported by the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic (No. 00023728).

We are indebted to Dr. Javier Martin (Instituto de Parasitología y Biomedicina, Granada, Spain) for supplying Spanish control data, Dr. Peter Novota (Institute of Rheumatology, Prague, Czech Republic) for supplying Czech controls and Dr. Lars Alfredsson (Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden) for Swedish control data. We thank Dr. Younghun Han (Dartmouth College) for statistical support, Miss Hazel Platt and Mrs. Fiona Marriage (Centre for Integrated Genomic Medical Research, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) and Drs. Maryam Dastmalchi and Eva Jemseby (Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden) for technical support, Mr. Paul New (Salford Royal Foundation Trust, Salford, UK) for ethical and technical support, Sue Edelstein (Image Associates, Inc., Durham, NC) for graphics support, and Lisa Maroski for assistance in manuscript preparation.

We thank Dr. Elaine Remmers (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Bethesda, MD) and Dr. Douglas Bell (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, NC) of the National Institutes of Health for their critical review of the manuscript.

We thank the other study investigators of the Myositis Genetics Consortium: Drs. Christopher Denton (Royal Free Hospital, London, UK), David Hilton-Jones (John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK), Patrick Kiely (St. George’s Hospital, London, UK), Paul H. Plotz, Mark Gourley (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and Hemlata Varsani (University College London, London, UK).

We thank members of the UK Adult Onset Myositis Immunogenetic Collaboration who recruited and enrolled subjects: Drs. Yasmeen Ahmed (Llandudno General Hospital), Raymond Armstrong (Southampton General Hospital), Robert Bernstein (Manchester Royal Infirmary), Carol Black (Royal Free Hospital, London), Simon Bowman (University Hospital, Birmingham), Ian Bruce (Manchester Royal Infirmary), Robin Butler (Robert Jones & Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital, Oswestry), John Carty (Lincoln County Hospital), Chandra Chattopadhyay (Wrightington Hospital), Easwaradhas Chelliah (Wrightington Hospital), Fiona Clarke (James Cook University Hospital, Middlesborough), Peter Dawes (Staffordshire Rheumatology Centre, Stoke on Trent), Joseph Devlin (Pinderfields General Hospital, Wakefield), Christopher Edwards (Southampton General Hospital), Paul Emery (Academic Unit of Musculoskeletal Disease, Leeds), John Fordham (South Cleveland Hospital, Middlesborough), Alexander Fraser (Academic Unit of Musculoskeletal Disease, Leeds), Hill Gaston (Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge), Patrick Gordon (King’s College Hospital, London), Bridget Griffiths (Freeman Hospital, Newcastle), Harsha Gunawardena (Frenchay Hospital, Bristol), Frances Hall (Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge), Beverley Harrison (North Manchester General Hospital), Elaine Hay (Staffordshire Rheumatology Centre, Stoke on Trent), Lesley Horden (Dewsbury District General Hospital), John Isaacs (Freeman Hospital, Newcastle), Adrian Jones (Nottingham University Hospital), Sanjeet Kamath (Staffordshire Rheumatology Centre, Stoke on Trent), Thomas Kennedy (Royal Liverpool Hospital), George Kitas (Dudley Group Hospitals Trust, Birmingham), Peter Klimiuk (Royal Oldham Hospital), Sally Knights (Yeovil District Hospital, Somerset), John Lambert (Doncaster Royal Infirmary), Peter Lanyon (Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham), Ramasharan Laxminarayan (Queen’s Hospital, Burton Upon Trent), Bryan Lecky (Walton Neuroscience Centre, Liverpool), Raashid Luqmani (Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, Oxford), Jeffrey Marks (Steeping Hill Hospital, Stockport), Michael Martin (St. James University Hospital, Leeds), Dennis McGonagle (Academic Unit of Musculoskeletal Disease, Leeds), Neil McHugh (Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath), Francis McKenna (Trafford General Hospital, Manchester), John McLaren (Cameron Hospital, Fife), Michael McMahon (Dumfries & Galloway Royal Infirmary, Dumfries), Euan McRorie (Western General Hospital, Edinburgh), Peter Merry (Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital, Norwich), Sarah Miles (Dewsbury & District General Hospital, Dewsbury), James Miller (Royal Victoria Hospital, Newcastle), Anne Nicholls (West Suffolk Hospital, Bury St. Edmunds), Jennifer Nixon (Countess of Chester Hospital, Chester), Voon Ong (Royal Free Hospital, London), Katherine Over (Countess of Chester Hospital, Chester), John Packham (Staffordshire Rheumatology Centre, Stoke on Trent), Nicolo Pipitone (King’s College Hospital, London), Michael Plant (South Cleveland Hospital, Middlesborough), Gillian Pountain (Hinchingbrooke Hospital, Huntington), Thomas Pullar (Ninewells Hospital, Dundee), Mark Roberts (Salford Royal Foundation Trust), Paul Sanders (Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester), David Scott (King’s College Hospital, London), David Scott (Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital, Norwich), Michael Shadforth (Staffordshire Rheumatology Centre, Stoke on Trent), Thomas Sheeran (Cannock Chase Hospital, Cannock, Staffordshire), Arul Srinivasan (Broomfield Hospital, Chelmsford), David Swinson (Wrightington Hospital), Lee-Suan Teh (Royal Blackburn Hospital, Blackburn), Michael Webley (Stoke Manderville Hospital, Aylesbury), Brian Williams (University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff), and Jonathan Winer (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham).

We thank members of the UK Juvenile Dermatomyositis Research Group who recruited and enrolled subjects: Dr. Kate Armon, Mr. Joe Ellis-Gage, Ms. Holly Roper, Ms. Vanja Briggs, and Ms. Joanna Watts (Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals); Dr. Liza McCann, Mr. Ian Roberts, Dr. Eileen Baildam, Ms. Louise Hanna, and Ms. Olivia Lloyd (The Royal Liverpool Children’s Hospital, Alder Hey, Liverpool); Dr. Phil Riley and Ms. Ann McGovern (Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Manchester); Dr. Clive Ryder, Mrs. Janis Scott, Mrs. Beverley Thomas, Professor Taunton Southwood, and Dr. Eslam Al-Abadi (Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham);Dr. Sue Wyatt, Mrs. Gillian Jackson, Dr. Tania Amin, Dr. Mark Wood, Dr. Vanessa Van Rooyen, and Ms. Deborah Burton (Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds);Dr. Joyce Davidson, Dr. Janet Gardner-Medwin, Dr. Neil Martin, Ms. Sue Ferguson, Ms. Liz Waxman, and Mr. Michael Browne (The Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Yorkhill, Glasgow);Dr. Mark Friswell, Professor Helen Foster, Mrs. Alison Swift, Dr. Sharmila Jandial, Ms. Vicky Stevenson, Ms. Debbie Wade, Dr. Ethan Sen, Dr. Eve Smith, Ms. Lisa Qiao, and Mr. Stuart Watson (Great North Children’s Hospital, Newcastle); Dr. Helen Venning, Dr. Rangaraj Satyapal, Mrs. Elizabeth Stretton, Ms. Mary Jordan, Dr. Ellen Mosley, Ms. Anna Frost, Ms. Lindsay Crate, and Dr. Kishore Warrier (Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham);Professor Lucy Wedderburn, Dr. Clarissa Pilkington, Dr. N. Hasson, Mrs. Sue Maillard, Ms. Elizabeth Halkon, Ms. Virginia Brown, Ms. Audrey Juggins, Dr. Sally Smith, Mrs. Sian Lunt, Ms. Elli Enayat, Mrs. Hemlata Varsani, Miss Laura Kassoumeri, Miss Laura Beard, Miss Katie Arnold, Mrs. Yvonne Glackin, Miss Stephanie Simou, and Dr. Beverley Almeida (Great Ormond Street Hospital, London); Dr. Kevin Murray (Princess Margaret Hospital, Perth, Western Australia); Dr. John Ioannou and Ms. Linda Suffield (University College London Hospital); Dr. Muthana Al-Obaidi, Ms. Helen Lee, Ms. Sam Leach, and Ms. Helen Smith (Sheffield’s Children’s Hospital); and Dr. Nick Wilkinson, Ms. Emma Inness, Ms. Eunice Kendall, and Mr. David Mayers (Oxford University Hospitals).

We thank the following members of the US Childhood Myositis Heterogeneity Study Group who recruited and enrolled subjects: Drs. Barbara S. Adams (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), Catherine A. Bingham (Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA), Gail D. Cawkwell (All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, FL), Terri H. Finkel (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA), Steven W. George (Ellicott City, MD), Harry L. Gewanter (Richmond, VA), Ellen A. Goldmuntz (Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC), Donald P. Goldsmith (St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA), Michael Henrickson (Children’s Hospital, Madera, CA), Lisa Imundo (Columbia University, New York, NY), Ildy M. Katona (Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD), Carol B. Lindsley (University of Kansas, Kansas City), Chester P. Oddis (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA), Judyann C. Olson (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee), David Sherry (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA), Scott A. Vogelgesang (Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC), Carol A. Wallace (Children’s Medical Center, Seattle, WA), Patience H. White (George Washington University, Washington, DC), and Lawrence S. Zemel (Connecticut Children’s Hospital, Hartford).

Footnotes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Table S1. Loci with HLA typing data available.

Table S2. Heterogeneity of HLA-C*07:01 and HLA-DQA1*05:01 alleles among the five geographic groups.

Table S3 Genome-wide significant SNPs after conditioning on DRB1*03:01 in meta-analysis of five geographical groups for all myositis cases and controls as shown in Figure 2, Panel B. Results from before conditioning are also listed for comparison.

Table S4. Genotypic effects of the most significant loci for myositis phenotypes.

Table S5. Risk estimates from dominant models for myositis phenotypes.

References

- 1.Parkes M, Cortes A, van Heel DA, Brown MA. Genetic insights into common pathways and complex relationships among immune-mediated diseases. Nat.Rev.Genet. 2013;14(9):661–673. doi: 10.1038/nrg3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricano-Ponce I, Wijmenga C. Mapping of immune-mediated disease genes. Annu.Rev.Genomics Hum.Genet. 2013;14:325–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rider LG, Miller FW. Deciphering the clinical presentations, pathogenesis, and treatment of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305(2):183–190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginn LR, Lin JP, Plotz PH, et al. Familial autoimmunity in pedigrees of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy patients suggests common genetic risk factors for many autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(3):400–405. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199803)41:3<400::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niewold TB, Wu SC, Smith M, Morgan GA, Pachman LM. Familial aggregation of autoimmune disease in juvenile dermatomyositis. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1239–e1246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott AP, Laing NG, Mastaglia F, et al. Recombination mapping of the susceptibility region for sporadic inclusion body myositis within the major histocompatibility complex. J Neuroimmunol. 2011 Jun;235(1–2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Hanlon TP, Carrick DM, Targoff IN, et al. Immunogenetic Risk and Protective Factors for the Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies: Distinct HLA-A, -B, -Cw, -DRB1, and -DQA1 Allelic Profiles Distinguish European American Patients With Different Myositis Autoantibodies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85(2):111–127. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000217525.82287.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chinoy H, Salway F, Fertig N, et al. In adult onset myositis, the presence of interstitial lung disease and myositis specific/associated antibodies are governed by HLA class II haplotype, rather than by myositis subtype. Arthritis Res.Ther. 2006;8(1):R13. doi: 10.1186/ar1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trowsdale J, Knight JC. Major histocompatibility complex genomics and human disease. Annu.Rev.Genomics Hum.Genet. 2013;14:301–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horton R, Gibson R, Coggill P, et al. Variation analysis and gene annotation of eight MHC haplotypes: the MHC Haplotype Project. Immunogenetics. 2008;60(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0262-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller FW. Inflammatory Myopathies: Polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and related conditions. In: Koopman W, Moreland L, editors. Arthritis and Allied Conditions, A Textbook of Rheumatology. Vol. 15. Philadelphia: Lippincott: Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1593–1620. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer A, Meyer N, Schaeffer M, Gottenberg JE, Geny B, Sibilia J. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory myopathies: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54(1):50–63. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller FW, Cooper RG, Vencovsky J, et al. Genome-wide association study of dermatomyositis reveals genetic overlap with other autoimmune disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(12):3239–3247. doi: 10.1002/art.38137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell MK, Gregersen PK, Johnson S, Parsons R, Vlahov D New York Cancer P. The New York Cancer Project: rationale, organization, design, and baseline characteristics. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2004 Jun;81(2):301–310. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wellcome Trust Case Control C. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, et al. TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis--a genomewide study. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(12):1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Hanlon TP, Miller FW. Genetic risk and protective factors for the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Curr Rheumatol.Rep. 2009;11(4):287–294. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinoy H, Lamb JA, Ollier WE, Cooper RG. Recent advances in the immunogenetics of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Arthritis Res.Ther. 2011;13(3):216. doi: 10.1186/ar3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinoy H, Payne D, Poulton KV, et al. HLA-DPB1 associations differ between DRB1*03 positive anti-Jo-1 and anti-PM-Scl antibody positive idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(10):1213–1217. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinto D, Darvishi K, Shi X, et al. Comprehensive assessment of array-based platforms and calling algorithms for detection of copy number variants. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29(6):512–520. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassan AB, Nikitina-Zake L, Sanjeevi CB, Lundberg IE, Padyukov L. Association of the proinflammatory haplotype (MICA5.1/TNF2/TNFa2/DRB1*03) with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(3):1013–1015. doi: 10.1002/art.20208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love LA, Leff RL, Fraser DD, et al. A new approach to the classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: myositis-specific autoantibodies define useful homogeneous patient groups. Medicine (Baltimore) 1991;70(6):360–374. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199111000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller FW. Myositis-specific autoantibodies Touchstones for understanding the inflammatory myopathies. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270(15):1846–1849. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.15.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rider LG, Shah M, Mamyrova G, et al. The myositis autoantibody phenotypes of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2013;92(4):223–243. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31829d08f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casciola-Rosen L, Mammen AL. Myositis autoantibodies. Curr.Opin.Rheumatol. 2012;24(6):602–608. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328358bd85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheet P, Stephens M. A fast and flexible statistical model for large-scale population genotype data: applications to inferring missing genotypes and haplotypic phase. Am J Hum Genet. 2006 Apr;78(4):629–644. doi: 10.1086/502802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Candore G, Lio D, Colonna RG, Caruso C. Pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases associated with 8.1 ancestral haplotype: effect of multiple gene interactions. Autoimmun.Rev. 2002;1(1–2):29–35. doi: 10.1016/s1568-9972(01)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price P, Witt C, Allcock R, et al. The genetic basis for the association of the 8.1 ancestral haplotype (A1, B8, DR3) with multiple immunopathological diseases. Immunol.Rev. 1999;167:257–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chinoy H, Salway F, John S, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha single nucleotide polymorphisms are not independent of HLA class I in UK Caucasians with adult onset idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(9):1411–1416. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chinoy H, Adimulam S, Marriage F, et al. Interaction of HLA-DRB1*03 and smoking for the development of anti-Jo-1 antibodies in adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: a European-wide case study. Ann.Rheum.Dis. 2012;71(6):961–965. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothwell S, Cooper RG, Lamb JA, Chinoy H. Entering a new phase of immunogenetics in the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Curr.Opin.Rheumatol. 2013;25(6):735–741. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000434676.70268.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaslow RA, Shaw S. The role of histocompatibility antigens (HLA) in infection. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1981;3:90–114. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie Z, Chang C, Zhou Z. Molecular mechanisms in autoimmune type 1 diabetes: a critical review. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2014;47(2):174–192. doi: 10.1007/s12016-014-8422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Candore G, Campagna AM, Cuppari I, Di CD, Mineo C, Caruso C. Genetic control of immune response in carriers of the 8.1 ancestral haplotype: correlation with levels of IgG subclasses: its relevance in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1110:151–158. doi: 10.1196/annals.1423.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Candore G, Balistreri CR, Campagna AM, et al. Genetic control of immune response in carriers of ancestral haplotype 8.1: the study of chemotaxis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1089:509–515. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olivares M, Laparra JM, Sanz Y. Host genotype, intestinal microbiota and inflammatory disorders. British Journal of Nutrition. 2013;109(Suppl 2):S76–S80. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512005521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivares M, Neef A, Castillejo G, et al. The HLA-DQ2 genotype selects for early intestinal microbiota composition in infants at high risk of developing coeliac disease. Gut. 2014 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bohan A, Peter JB, Bowman RL, Pearson CM. Computer-assisted analysis of 153 patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977;56:255–286. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Targoff IN, Trieu EP, Miller FW. Reaction of anti-OJ autoantibodies with components of the multi- enzyme complex of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in addition to isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;91:2556–2564. doi: 10.1172/JCI116493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rich SS, Concannon P, Erlich H, et al. The Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1079:1–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1375.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erlich HA, Lohman K, Mack SJ, et al. Association analysis of SNPs in the IL4R locus with type I diabetes. Genes Immun. 2009;10(Suppl 1):S33–S41. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Concannon P, Chen WM, Julier C, et al. Genome-wide scan for linkage to type 1 diabetes in 2,496 multiplex families from the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium. Diabetes. 2009;58(4):1018–1022. doi: 10.2337/db08-1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mastaglia FL, Needham M, Scott A, et al. Sporadic inclusion body myositis: HLA-DRB1 allele interactions influence disease risk and clinical phenotype. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2009;19(11):763–765. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003 Jan;19(1):149–150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analysis methods for genome-wide association studies and beyond. Nat.Rev.Genet. 2013;14(6):379–389. doi: 10.1038/nrg3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Begum F, Ghosh D, Tseng GC, Feingold E. Comprehensive literature review and statistical considerations for GWAS meta-analysis. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40(9):3777–3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.