Abstract

Background

The ability to grow in phosphorus-depleted soils is an important trait for rice cultivation in many world regions, especially in the tropics. The Phosphorus Starvation Tolerance 1 (PSTOL1) gene has been identified as underlying the ability of some cultivated rice varieties to grow under low-phosphorus conditions; however, the gene is absent from other varieties. We assessed PSTOL1 presence/absence in a geographically diverse sample of wild, domesticated and weedy rice and sequenced the gene in samples where it is present.

Results

We find that the presence/absence polymorphism spans cultivated, weedy and wild Asian rice groups. For the subset of samples that carry PSTOL1, haplotype sequences suggest long-term selective maintenance of functional alleles, but with repeated evolution of loss-of-function alleles through premature stops and frameshift mutations. The loss-of-function alleles have evolved convergently in multiple rice species and cultivated rice varieties. Greenhouse assessments of plant growth under low- and high-phosphorus conditions did not reveal significant associations with PSTOL1 genotype variation; however, the striking signature of balancing selection at this locus suggests that further phenotypic characterizations of PSTOL1 allelic variants is warranted and may be useful for crop improvement.

Conclusions

These findings suggest balancing selection for both functional and non-functional PSTOL1 alleles that predates and transcends Asian rice domestication, a pattern that may reflect fitness tradeoffs associated with geographical variation in soil phosphorus content.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-016-0783-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Balancing selection, Crop domestication, Gene presence/absence variation (PAV), Phosphorus Starvation Tolerance 1 (PSTOL1), Weedy rice, Abiotic stress

Background

Abiotic stresses, such as drought, high salinity and low soil nutrient levels, negatively impact crop production worldwide and are predicted to increase in coming decades due to climate change [1, 2]. Much work has focused on identifying molecular mechanisms of abiotic stress tolerance in plants with the goal of breeding more tolerant crops [3, 4]. However, the genetic basis of plant adaptation to abiotic stress remains poorly understood, even in genomic model species such as rice. Identification of stress tolerance genes is often limited to mutant lines or a relatively few individuals used in mapping populations, and wider analysis of natural allelic variants in cultivated and wild populations is rare (but see [5–7]).

One factor that may shape the evolution of abiotic stress adaptation is fitness trade-offs in contrasting environments, where genotypes that can tolerate abiotic stress show reduced competitive ability or yields when grown in more favorable conditions. At the genetic level, antagonistic pleiotropy describes genotypes that are adaptive in one environment but that negatively impact fitness in another [8, 9]. Fitness trade-offs for stress tolerance may be especially important for crops such as rice (Oryza sativa), where cultivated varieties show tremendous variation in their agroecological adaptations. In rice this range includes upland, drought-tolerant varieties; deep-water varieties that grow in monsoon-flooded fields; short-season, cold-adapted varieties grown at high elevations and latitudes; and varieties with high tolerance to salinity and nutrient-poor soils [10].

Rice is the primary staple food for over one-third of the world’s population [11], and rice cultivation extends over 80 nations spanning six continents [10]. Soil phosphorus (P) availability varies widely across rice production areas. A large proportion of crop varieties are grown in P-depleted soils, particularly in upland regions of tropical Asia [12, 13]. At the same time, rice is also widely cultivated in P-rich or P-supplemented soils, and the varieties grown in these conditions are typically high yielding but intolerant of nutrient deprivation. This pattern suggests potential fitness trade-offs associated with tolerance of nutrient-poor soils. At the genetic level, if spatial heterogeneity in soil P availability has selected for both low-P-tolerant and -intolerant genotypes, then genes underlying this adaptive variation would be expected to evolve under balancing selection to maintain both allele classes. To the extent that soil nutrient heterogeneity also affects populations of rice’s wild and weedy relatives, non-cultivated Oryza populations could also be subject to balancing selection for low-P tolerance.

Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa) consists of two major subspecies, japonica and indica, which were domesticated from wild rice, O. rufipogon, starting about 8000 years ago [14]. The indica subspecies consists of indica and aus varieties, and the japonica subspecies consists of tropical japonica, temperate japonica, and aromatic varieties. All five cultivated variety groups can be distinguished genetically [15]. In addition to domestication, Asian rice has also undergone de-domestication, leading to conspecific weedy strains that infest crop fields. Several genetically distinct weedy rice populations have been described, including straw-hulled U.S. weeds derived from indica crop progenitors [16], black-hulled U.S. weeds from aus progenitors [16], Korean weeds from indica progenitors [17], Korean weeds from japonica progenitors [17], and Malaysian weeds from indica progenitors [18]. In Africa, an independent domestication event starting about 3500 years ago led to African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima), which is derived from the wild African species Oryza barthii [19, 20]. Both Asian and African domesticated rice belong to the AA genome Oryza species clade, which, in addition to their wild progenitor species, includes the South American species O. glumaepatula, the Australian species O. meridionalis, and the African species O. longistaminata [21].

Phosphorus Starvation Tolerance 1 (PSTOL1) has recently been identified as a major genetic determinant of low-P tolerance in rice [22]. This gene, which encodes a protein kinase conferring P starvation tolerance, was identified in a low-P tolerant aus rice cultivar, Kasalath [23]. Interestingly, PSTOL1 was found to be absent from the rice reference genome (Nipponbare, a temperate japonica variety), where it falls within a ~90 kb insertion-deletion polymorphism (indel) on chromosome 12. Prior to the functional characterization of PSTOL1 by Gamuyao et al., this ~90 kb indel was identified as widely polymorphic across Asian rice varieties; insertions are associated with upland rice grown in poor soil conditions, and deletions are associated with lowland rice grown in favorable soil conditions [13]. Given that the ~90 kb indel likely corresponds to PSTOL1 presence/absence, this pattern suggests that the PSTOL1 presence/absence variation could potentially reflect geographically heterogeneous selection for low-P-tolerant and -intolerant genotypes.

Although PSTOL1 appears to be an important gene underlying adaptation of cultivated rice to poor soil environments, sequence variation at this locus has only been directly examined in a handful of cultivars [22, 24]. In this study we report on PSTOL1 molecular evolution and distribution of the gene presence/absence polymorphism across wild, cultivated and weedy rice. Using these data we address the following questions: 1) What does the distribution of PSTOL1 presence/absence variation across cultivated, weedy and wild rice tell us about long-term evolution of adaptation to low-P soil conditions? 2) For plants that carry PSTOL1, what does the molecular evolution of this gene reveal about mechanisms of selection on functional variation? 3) How does PSTOL1 variation correspond to phenotypic variation for low-P tolerance in rice plants grown under controlled greenhouse conditions? Our results suggest long-term balancing selection at the PSTOL1 locus that predates and transcends rice domestication, with strong and persistent selection to maintain both functional and nonfunctional alleles at this agronomically important gene.

Results

Phylogenetic distribution of the PSTOL1 presence/absence polymorphism

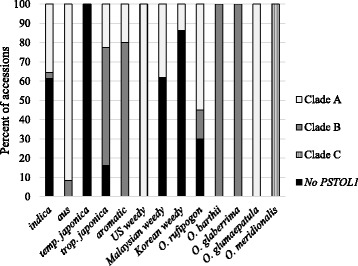

Of the 282 screened plants, 160 (56.7 %) carried PSTOL1 and 122 (43.3 %) were negative for all PCR-genotyping reactions (Fig. 1; Additional file 1: Table S1). Across the six AA genome Oryza species sampled, all accessions of O. barthii, O. glaberrima, O. glumaepatula and O. meridionalis were found to carry the gene. In contrast, the gene was absent in 30 % of O. rufipogon samples and 52 % of O. sativa samples. These patterns suggest that the PSTOL1 presence/absence polymorphism is restricted to Asian cultivated rice and its wild progenitor. Within O. sativa, the presence/absence polymorphism spans both the indica and japonica subspecies. PSTOL1 was present in all aus and aromatic crop samples (belonging to the indica and japonica subspecies, respectively), as well as all US weed accessions (indica subspecies), while it was absent from all temperate japonica samples. Indica and tropical japonica crop varieties were polymorphic, as were Malaysian and Korean weeds (which comprise a combination of indica and japonica strains).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of PSTOL1 presence absence polymorphism and clade type. Absence of PSTOL1 was recorded when no PCR product was produced for any of three sets of primers. Early stop mutations are included in the clade type percentages

Additional loss-of-function mutations at PSTOL1

Although the PSTOL1 presence/absence polymorphism is restricted to O. sativa and O. rufipogon in the sampled accessions, the gene appears to have independently evolved loss-of-function alleles across multiple species through other mutational events (Fig. 2). Among the subset of samples that carry the gene, a 2-bp frameshift deletion at nucleotide positions 381–382 was detected in all six O. meridionalis accessions; this deletion was also detected in one of the five O. glumaepatula accessions. Within O. sativa, a G to A substitution at position 411, which results in a premature stop codon at amino acid position 137, was detected in an indica crop variety and four Korean indica-like weeds. Interestingly, the same codon is altered through an independent premature stop detected in five aus varieties and one O. rufipogon accession; these samples carry a G to A substitution at nucleotide position 410. Thus, the occurrence of both functional and nonfunctional PSTOL1 alleles spans multiple AA genome Oryza species, and the variation in PSTOL1 functionality within O. rufipogon and O. sativa includes both presence/absence variation and loss-of-function mutations. This pattern is consistent with taxonomically- and geographically-widespread selection to maintain polymorphism in PSTOL1 functionality.

Fig. 2.

Location of early stop mutations in PSTOL1 gene. PSTOL1 consists of a single 975 bp exon. Two different nonsense mutations are located in the same codon (bp 410 and 411). The 410 G to A mutation results in early stop in five aus accessions and the 411 G to A mutation results in early stop in one indica and four Korean weed accessions. A two basepair deletion at 381 leads to an early stop in a single O. glumaepatula accession and six O. meridionalis accessions

Evolutionarily diverged PSTOL1 clades and signatures of balancing selection

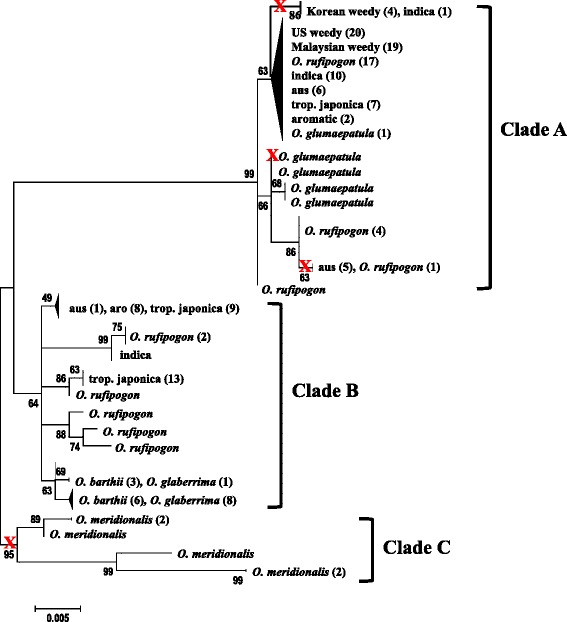

Phylogenetic analysis of PSTOL1 sequences revealed divergence between O. meridionalis, the most distantly related of the sampled AA genome species [21], and the other sampled taxa (Fig. 3, Clade C). For the remaining samples, sequences fell into two well supported and highly diverged clades (Clades A and B), which are separated by 27 mutational steps including 14 nonsynonymous substitutions. Clade distributions among the sampled accessions are shown in Table 1 and in Figs. 1 and 3. Haplotypes of O. glumaepatula and African rice (O. barthii and O. glaberrima) are grouped by species, with O. glumaepatula sequences in Clade A and African rice sequences in Clade B (Fig. 3). In contrast, haplotypes of both wild and domesticated Asian rice are present in both clades. Within O. sativa, three of the four cultivated variety groups that carry PSTOL1 are also present in both clades (indica, aus, tropical japonica), with no apparent correlation between clade divergence and indica/japonica subspecies designation. Given the deep divergence between the two clades and the incongruence of O. rufipogon/sativa haplotypes with known species relationships, these distributions suggest long-term selective maintenance of both the A and B allele classes in Asian rice. Consistent with this inference, frequency spectrum-based tests of neutral equilibrium revealed statistically significant signatures of balancing selection for tropical japonica sequences (Tajima’s D = 2.43, P < 0.001; Fu and Li’s FS = 2.25, P < 0.001), although deviations from neutrality were not significant for aus, aromatic or O. rufipogon samples (Table 1). A statistically significant signature of directional selection was found in indica samples (Tajima’s D = −2.26, P < 0.001; Fu and Li’s FS = 3.08, P < 0.001), likely due to only 1 of 12 accessions possessing the B clade allele.

Fig. 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny of PSTOL1. Parentheses contain numbers of accessions within a group. Bootstrap values are percentages from 10,000 replicates. The red X symbol indicates locations of early stop mutations

Table 1.

Summary statistics of PSTOL1 nucleotide variation by rice group

| Oryza group | Clade | No. accessions | No. Segregating Sites | π | θW | Tajima’s D | Fu & Li’s FS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O. sativa | |||||||

| - indica | A & B | 12 | 38 | 0.0115 | 0.0226 | −2.2578** | 3.0801** |

| - aus | A & B | 12 | 34 | 0.0196 | 0.0276 | −1.3584 | −2.1365* |

| - tropical japonica | A & B | 26 | 34 | 0.0394 | 0.0235 | 2.4304** | 2.2530** |

| - aromatic | A & B | 10 | 34 | 0.0291 | 0.0315 | −0.2841 | 0.7705 |

| All cultivated | A & B | 60 | 47 | 0.0451 | 0.0267 | 2.3701 | 1.0783 |

| - US weedy | A | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| - Malaysian weedy | A | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| - Korean weedy | A | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| All weedy | A | 43 | 2 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| O. rufipogon | A & B | 28 | 56 | 0.0397 | 0.0150 | −0.2705 | −0.1811 |

| O. barthii | B | 9 | 3 | 0.0011 | 0.0018 | 0.0253 | 0.2023 |

| O. glaberrima | B | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | −1.5130* | −1.9338* |

| O. meridionalis | C | 6 | 22 | 0.0202 | - | 0.9752 | 1.0558 |

| O. glumaepatula | A | 5 | 25 | 0.0328 | 0.0369 | −0.9924 | −1.0669 |

Pi and Theta are per base pair at silent sites

10,000 coalescent simulations for significance values

*p-value < 0.05

**p-value < 0.001

It is important to note that BLAST searches using PSTOL1 sequences from each of the major clades revealed no evidence for additional PSTOL1 gene copies in published databases, nor did we ever amplify both Clade A and B haplotypes in the same accession. Thus, the A and B clades appear to be highly diverged alleles of the same gene rather than paralogous and/or pseudogenized gene copies. Interestingly, O. sativa and O. rufipogon sequences with premature stop mutations occur exclusively within Clade A (Fig. 3), which might further point to some difference in functionality between the A and B allele classes.

Comparisons of nucleotide diversity between Asian domesticated rice and its wild progenitor further suggest non-neutral evolution at PSTOL1. Whereas neutrally evolving genes across the rice genome show evidence of a domestication bottleneck, with a lower diversity in the crop compared to O. rufipogon [25], PSTOL1 nucleotide diversity is instead higher in cultivated rice (see π and θW values, Table 1). This pattern suggests that balancing selection has maintained elevated diversity at this locus through the domestication event. Consistent with this finding, we observed a high, albeit non-significant, value for Tajima’s D for all cultivated rice samples pooled (Tajima’s D = 2.37, P > 0.05). In contrast to O. sativa, African domesticated rice (O. glaberrima) showed no evidence of balancing selection at PSTOL1 during domestication; diversity is lower in the crop than its wild progenitor, consistent with neutral evolution during the African rice domestication bottleneck [20].

For weedy rice strains, patterns of nucleotide diversity at PSTOL1 are consistent with demographic bottlenecks that occurred as these weeds evolved from their domesticated progenitors (e.g., [16, 18]). US weeds are fixed for a single, common Clade A haplotype, which is also present in both indica and aus cultivated variety groups (the inferred progenitors to US weeds; [16]) (Fig. 3). All Malaysian weeds also share this common clade A haplotype, consistent with their close relationship to indica crop varieties [18]. The four indica-like Korean weed accessions that carry PSTOL1 are fixed for a different Clade A haplotype; as with the other weedy rice haplotypes, this haplotype is shared with an indica crop accession (Fig. 3).

Greenhouse growth experiments

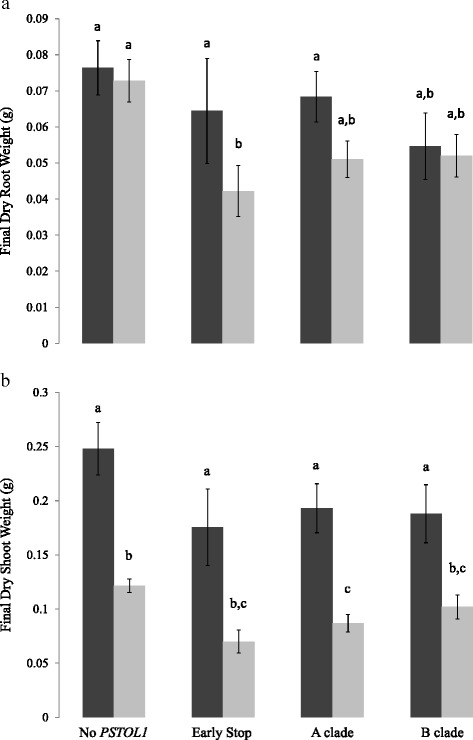

In contrast to the findings of Gamuyao et al. [22], comparisons of genotype performance in low- vs. high-P conditions did not reveal an obvious fitness advantage for plants with functional PSTOL1 gene copies under low-P conditions. Although plants with functional gene copies showed a non-significant trend towards better growth under low-P conditions than those with premature stop mutations, the plants that performed best of all were those that lack the gene altogether; these results were consistent for both root and shoot growth (Fig. 4a, b, Additional file 2: Figure S2 and Additional file 3: Figure S3). We also found no major difference in root or shoot growth between the two major allele classes (Clades A and B) when plants were grown under low-P conditions. Under high-P conditions, plants grew larger shoots than plants grown in low-P conditions regardless of PSTOL1 genotype (Fig. 4b and Additional file 3: Figure S3). Root growth did not show significant differences between high- and low-P conditions for plants other than those with premature stop mutations, where root weight was greater under high-P conditions (Fig. 4a and Additional file 2: Figure S2), and for those that lack PSTOL1, where roots were longer in low-P conditions (Additional file 4: Figure S1). While our greenhouse experiment was modeled on the methods of Gamuyao et al., our failure to detect the phenotypic associations with PSTOL1 variation observed in that study may reflect differences in experimental design, including differences in the developmental stages assayed. Two other recent studies have also reported no clear correlation between PSTOL1 genotypic variation and plant performance in high- vs. low-P conditions [26, 27].

Fig. 4.

Performance of PSTOL1 genotypes in low and high phosphorus conditions. Plants were measured after 21 days in high phosphorus (black) and low phosphorus (grey) media. a dry root weight; b dry shoot weight

Discussion

PSTOL1 is a highly polymorphic gene in AA genome Oryza species. We find evidence for the selective maintenance of the gene presence/absence polymorphism across domesticated Asian rice and its wild progenitor (Fig. 1), independent evolution of loss-of-function alleles though nonsense and frameshift mutations (Fig. 2), and maintenance of two distinct clades of functional alleles in Asian rice that bear clear signatures of balancing selection (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The divergence of these two PSTOL1 clades likely predates Asian rice domestication, as alleles from both clades are found in wild rice (O. rufipogon) accessions (Figs. 1 and 3). There is also evidence of long-term balancing selection to maintain the two separate clades across several cultivated rice groups (Table 1). These findings raise intriguing questions on the selective factors that have maintained this functional variation and its implications for adaptation to high- and low-P environments.

Functional implications of PSTOL1 variation

There is abundant evidence that PSTOL1 confers increased uptake of phosphorus in plants that possess functional copies of the gene. This gene, which encodes a receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase [22], was identified through fine mapping of a major QTL for P uptake, Pup1, which had been found to explain nearly 80 % of the variation in this trait between Kasalath and the Nipponbare [28]. PSTOL1 overexpression in two transgenic lines increased grain yield by more than 60 % under low-P conditions, with improved uptake of P and other nutrients arising through inreased root length and surface area [22]. In addition, a survey of 159 cultivated Asian rice accessions indicated that the Pup1 QTL was differentially represented in varieties adapted to unfavorable, stress-prone growing conditions [13]. Homologs of PSTOL1 have also been implicated in increased P-uptake efficiency in sorghum [29] and maize [30]. All of these findings would suggest that selection should strongly favor PSTOL1 functionality rice plants growing in stressful, low-P soil conditions.

Correspondingly, the phylogenetically and geographically widespread occurrence of loss-of function and gene-deletion alleles can most plausibly be explained as an instance of antagonistic pleiotropy, with energetic tradeoffs or other costs disfavoring PSTOL1 expression in environments with greater P availability. Whereas PSTOL1 has been completely lost in temperate japonica rice, functional copies are present in some indica, aus, tropical japonica and African cultivated rices, indicating that phosphorus starvation tolerance could be beneficial in parts of the regions where the latter varieties are cultivated. Transgenic expression experiments provide additional evidence that PSTOL1 likely has pleiotropic effects. For example, 35S:PSTOL1 overexpression lines cause changes in expression of genes related to root growth and stress response when compared PSTOL1 null lines [22]; affected genes include those involved in drought response and leaf senescence, two traits that are likely under strong selective constraints of their own. Examples of antagonistic pleiotropy are rare in plants, and further experiments with the PSTOL1 polymorphism will be required to definitively confirm that functional alleles are selected against in some environmental conditions.

Just as the polymorphism in PSTOL1 functionality is likely to reflect an adaptive polymorphism, the occurrence of two evolutionarily diverged clades within Asian rice also suggests balancing selection, in this case to maintain two functionally distinct allele classes. Clade A and B haplotypes differ by 14 nonsynonyous subsititutions (4.3 % amino acid divergence), and a subset of these amino acid differences could underlie functional differences in the protein kinase activity. However, the functional differences between Clade A and B alleles, if any, remain to be characterized. The well characterized Kasalath PSTOL1 allele falls within Clade A haplotypes (Additional file 1: Table S1), and studies to date on the phenotypic effects of PSTOL1 variation have either focused specifically on that allele [22, 28] or have assessed the Pup1/PSTOL1 polymorphism without information on underlying sequence variation [13, 26, 27]. Thus, as with the gene presence/absence polymorphism, further work is needed to assess functional differences between the major PSTOL1 haplotype clades.

Pariasca-Tanaka et al. [24] recently described an African rice PSTOL1 sequence that matches the Clade B haplotype we found in the majority of our African rice samples (see Fig. 3). They note that while differing at 6 % of amino acid sites from the Kasalath allele, the sequence is conserved in the kinase catalytic domain. Similarly, all but three accessions in our Clade B haplotypes also have a completely conserved kinase catalytic domain. The exceptions include two O. rufipogon accessions and one indica accession which each contain a single amino acid replacement in that domain. These findings suggest that if there are functional differences in the Clade A and B alleles, they most likely do not arise through alterations of the protein’s catalytic domain.

Given the previously documented evidence that PSTOL1 enhances P uptake under low-P conditions [13, 22, 28, 31] and our evidence of balancing selection at this locus (Fig. 3 and Table 1), it is somewhat surprising that we did not detect any obvious effects of PSTOL1 variation on plant growth in the greenhouse (Fig. 4). On the other hand, at least two other recent studies have also found no clear correlation between PSTOL1 genotypes and plant performance in high- and low-P environments. In a survey of 31 indica rice varieties, Sarkar et al. [27] reported that the Pup1 locus was only present in three of the nine varieties showing greatest efficiency in P uptake in low-and high-P soils. Similarly, Mukherjee et al. [26] found no association between PSTOL1 presence and P-deficiency tolerance in a study of 108 diverse Indian varieties. The latter study also assessed the effects of PSTOL1 presence on low-P tolerance using a panel of 180 recombinant inbred lines and again found no evidence that the gene confers increased P-uptake efficiency. Like all physiological responses to abiotic stress, P uptake efficiency is undoubtedly a complex trait, and as such the phenotypic effects of PSTOL1 would be expected to vary across genetic backgrounds and environments. It seems likely that the variable effects reported for PSTOL1 in different studies are a manifestation of these gene-by-gene and gene-by-environment interactions.

Balancing selection

The phylogenetic distribution of putatively functional and non-functional PSTOL1 alleles suggests that selection has maintained this functional polymorphism across multiple Oryza species (Figs. 1 and 3). Trans-specific polymorphisms are typically established when balancing selection has been acting on a gene for very long periods of time [32], indicating that the same differential selective pressures may have been acting in this genus long before the domestication of Asian rice. Examples of trans-specific polymorphism are rare; self-incompatibility loci provide one of the best examples of long term balancing selection in plants (reviewed by [33]). However, the selective pressures acting on self-incompatibility are due to negative frequency dependent selection, where rare alleles have a selective advantage over common alleles. Balancing selection on abiotic stress genes is instead likely due to differential selection based on variable environmental conditions.

One example of long term balancing selection on abiotic stress genes was found in two species of wild tomato Solanum peruvianum and S. chilense [34]. The C-repeat binding factor (CBF2) is involved in plant responses to cold and drought, environmental conditions that vary across Solanum species ranges. Mboup et al. found trans-species polymorphism at CBF2 that maintains signatures of balancing selection. Environmental heterogeneity is likely driving balancing selection in both CBF2 and PSTOL1, and is likely not limited to these two examples of abiotic stress tolerance genes. Genome-wide studies of polymorphism in plants have identified several genomic regions that have signatures of balancing selection (e.g. [35]), but few studies have looked across species for trans-species polymorphisms in closely related plants.

Conclusions

Agricultural environments exhibit a range of abiotic stresses including drought, low nutrient availability and high salinity. Geographical variation in these stresses can lead to balancing selection at loci that underlie adaptation to these stresses. Our findings for PSTOL1 suggest that adaptive variation at this gene has been a target of environmentally heterogeneous selection not only within cultivated rice, but also on a larger time frame and geographical scale that encompasses multiple AA genome Oryza species. While we did not observe clear phenotypic associations with PSTOL1 molecular variation in the greenhouse, the molecular signature of balancing selection we detect at this locus suggests that functional variation is important in the field — both in cultivated rice and wild Oryza species. It is likely that other genes involved in abiotic stress response will also show signatures of balancing selection in crop plants and their wild relatives.

Methods

PSTOL1 genotyping and sequence analysis

Rice seeds were obtained from germplasm collections of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) or from Dr. Beng Kah Song (Monash University Malaysia), who kindly provided Malaysian weedy rice samples. Plants were grown to the seedling stage (10–20 cm), and young leaf tissue was collected for DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted using Qiagen DNeasy kits or a modified CTAB extraction protocol [36]. DNA quality and quantity were determined using 0.8 % agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. In total, 282 plants were included in the analysis, representing six AA genome Oryza species: O. barthii (N = 9), O. glaberrima (N = 9), O. glumaepatula (N = 5), O. meridionalis (N = 6), O. rufipogon (N = 40), and O. sativa (N = 114 crop varieties, 99 weed accessions) (Additional file 1: Table S1).

The PSTOL1 presence/absence polymorphism was scored using three sets of PCR primers spanning different portions of the gene, which consists of a single exon of 975 bp (Additional file 5: Table S2). PCR amplifications followed standard protocols [36] and were optimized before large scale screening. Plants that yielded a negative PCR result at least twice for all three primer pairs were scored as absent for the PSTOL1 gene. If any of the three primer pairs individually yielded a product while the other two primer pairs were negative, the amplicon was sequenced; however, there were no cases where the resulting product had sequence similarity to PSTOL1, and these plants were therefore scored as negative. PCR cleanup was carried out using Wizard PCR cleanup kits. All amplicons were direct Sanger sequenced in both directions following previously described protocols [36].

PSTOL1 sequences were contiged, aligned and checked for quality using Phred/Phrap and BioLign version 4.0.6.2 (Tom Hall, http://en.bio-soft.net/dna/BioLign.html). Only high quality base calls (quality score of 30 or better) were retained. Alignments were trimmed to the start and stop codon for the PSTOL1 gene. Evidence for heterozygous SNPs (double peaks) was screened by eye and found to be absent in the dataset, consistent with the highly selfing nature of both cultivated and weedy rice.

A Maximum Likelihood tree was constructed using MEGA version 5 [37] with complete deletion of gaps and 10,000 bootstrap replicates. Tree construction employed a GTR plus gamma mutation model, which was selected using Akaike information criteria as implemented in Modeltest [38]. DnaSP version 5 [39] was used to calculate summary statistics for genetic diversity, including numbers of segregating sites, average pairwise nucleotide diversity at silent sites (π) with Jukes-Cantor correction, and Watterson’s estimator of θ at silent sites. Neutral-equilibrium models were tested by estimating Tajima’s D amd Fu’s FS statistics in DnaSP with 10,000 coalescent simulations to assess significance.

Phenotyping for low-phosphorus tolerance

Sensitivity to low-P growing conditions was measured by root growth in low and high phosphorus conditions in the greenhouse following the protocol of Gamuyao et al. [22], as well as by total shoot mass. Twenty-four accessions spanning the taxonomic sampling of the study were included in the experiment (Additional file 1: Table S1). These included six accessions that lack the PSTOL1 gene; four that have the gene but carry premature stop mutations that would be expected to render it nonfunctional (see Results); and fourteen with putatively functional gene copies. Seeds were germinated on wet filter paper, and three seedling replicates per accession were assayed for each phosphorus treatment. Gamuyao, et al. transferred seedlings after 3 days of germination; however, our seedlings had not all germinated until day 10. At 10 days after germination, seedlings were transferred into styrofoam trays suspended in Yoshida growth media [40], which was changed out every 3 days. High- and low-P growth conditions were established by making the concentration of NaH2PO4 in the media either 100 uM or 10 uM. Root length was measured every 3 days, and final dry root and shoot weight was taken after 21 days in growth media.

Ethics

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the results in this article are available in Genbank, KU922566 - KU922725.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by a grant from the NSF Plant Genome Research Program (IOS-1032023) to KMO. We thank Dr. Patrick Vigueira and Zach Arias for assistance in greenhouse experiments and phenotyping, Dr. Beng Kah Song (Monash University Malaysia) for Malaysian weedy rice samples, and members of the Olsen lab group for comments on the manuscript.

Funding

All funds for the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data were provided by NSF IOS-1032023.

Abbreviations

- P

phosphorus

Additional files

Oryza samples used in analyses. (XLSX 21 kb)

Dry Root Weights of PSTOL1 genotypes grown in low and high phosphorus conditions. Plants were measured after 21 days in high phosphorus (black) and low phosphorus (grey) media. (PDF 75 kb)

Dry Shoot Weights of PSTOL1 genotypes grown in low and high phosphorus conditions. Plants were measured after 21 days in high phosphorus (black) and low phosphorus (grey) media. (PDF 72 kb)

Root lengths of PSTOL1 genotypes grown in low and high phosphorus conditions. Plants were measured after 21 days in high phosphorus (black) and low phosphorus (grey) media. (PDF 60 kb)

PSTOL1 primers used in PCR genotyping and sequencing. (XLSX 8 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CV participated in the design of the study, the analysis of the sequence data, the collection and analysis of the greenhouse data, and helped draft the manuscript. LS participated in the collection of the sequence data. KO participated in the design of the study, the analysis of the data, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Cynthia C. Vigueira, Email: cvigueir@highpoint.edu

Linda L. Small, Email: small@wustl.edu

Kenneth M. Olsen, Email: kolsen@wustl.edu

References

- 1.Boyer JS. Plant productivity and environment. Science. 1982;218:443–8. doi: 10.1126/science.218.4571.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiermeier Q. Quest for climate-proof farms. Nature. 2015;523:396–7. doi: 10.1038/523396a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vij S, Tyagi AK. Emerging trends in the functional genomics of the abiotic stress response in crop plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2007;5:361–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins NC, Tardieu F, Tuberosa R. Quantitative trait loci and crop performance under abiotic stress: where do we stand? Plant Physiol. 2008;147:469–86. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Des Marais DL, McKay JK, Richards JH, Sen S, Wayne T, Juenger TE. Physiological Genomics of Response to Soil Drying in Diverse Arabidopsis Accessions. Plant Cell. 2012;24:893–914. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juenger TE. Natural variation and genetic constraints on drought tolerance. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16:274–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh BP, Jayaswal PK, Singh B, Singh PK, Kumar V, Mishra S, Singh N, Panda K, Singh NK. Natural allelic diversity in OsDREB1F gene in the Indian wild rice germplasm led to ascertain its association with drought tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Anderson JT, Willis JH, Mitchell-Olds T. Evolutionary genetics of plant adaptation. Trends Genet. 2011;27:258–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson JT, Lee CR, Rushworth C a, Colautti RI, Mitchell-Olds T. Genetic trade-offs and conditional neutrality contribute to local adaptation. Mol Ecol. 2013;22:699–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GRiSP (Global Rice Science Partnership). Rice almanac. 4th edition. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute; 2013. p. 283.

- 11.Khush GS. Origin, dispersal, cultivation and variation of rice. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;35:25–34. doi: 10.1023/A:1005810616885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobermann A, White PF. Strategies for nutrient management in irrigated and rainfed lowland rice systems. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst. 1999;53:1–18. doi: 10.1023/A:1009795032575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin JH, Lu X, Haefele SM, Gamuyao R, Ismail A, Wissuwa M, Heuer S. Development and application of gene-based markers for the major rice QTL Phosphorus uptake 1. Theor Appl Genet. 2010;120:1073–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Gross BL, Zhao Z. Archaeological and genetic insights into the origins of domesticated rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6190–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308942110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garris AJ, Tai TH, Coburn J, Kresovich S, McCouch S. Genetic structure and diversity in Oryza sativa L. Genetics. 2005;169:1631–8. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.035642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reagon M, Thurber CS, Gross BL, Olsen KM, Jia Y, Caicedo AL. Genomic patterns of nucleotide diversity in divergent populations of U.S. weedy rice. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung JW, Park YJ. Population structure analysis reveals the maintenance of isolated sub-populations of weedy rice. Weed Res. 2010;50:606–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.2010.00810.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song B-K, Chuah T-S, Tam SM, Olsen KM. Malaysian weedy rice shows its true stripes: wild Oryza and elite rice cultivars shape agricultural weed evolution in Southeast Asia. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:5003–17. doi: 10.1111/mec.12922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z-M, Zheng X-M, Ge S. Genetic diversity and domestication history of African rice (Oryza glaberrima) as inferred from multiple gene sequences. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123:21–31. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang M, Yu Y, Haberer G, Marri PR, Fan C, Goicoechea JL, Zuccolo A, Song X, Kudrna D, Ammiraju JSS, Cossu RM, Maldonado C, Chen J, Lee S, Sisneros N, de Baynast K, Golser W, Wissotski M, Kim W, Sanchez P, Ndjiondjop M-N, Sanni K, Long M, Carney J, Panaud O, Wicker T, Machado CA, Chen M, Mayer KFX, Rounsley S, et al. The genome sequence of African rice (Oryza glaberrima) and evidence for independent domestication. Nat Genet. 2014;46:982–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhu T, Xu P-Z, Liu J-P, Peng S, Mo X-C, Gao L-Z. Phylogenetic relationships and genome divergence among the AA- genome species of the genus Oryza as revealed by 53 nuclear genes and 16 intergenic regions. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2014;70:348–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gamuyao R, Chin JH, Pariasca-Tanaka J, Pesaresi P, Catausan S, Dalid C, Slamet-Loedin I, Tecson-Mendoza EM, Wissuwa M, Heuer S. The protein kinase Pstol1 from traditional rice confers tolerance of phosphorus deficiency. Nature. 2012;488:535–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Heuer S, Lu X, Chin JH, Tanaka JP, Kanamori H, Matsumoto T, De Leon T, Ulat VJ, Ismail AM, Yano M, Wissuwa M. Comparative sequence analyses of the major quantitative trait locus phosphorus uptake 1 (Pup1) reveal a complex genetic structure. Plant Biotechnol J. 2009;7:456–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Pariasca-Tanaka J, Chin JH, Dramé KN, Dalid C, Heuer S, Wissuwa M. A novel allele of the P-starvation tolerance gene OsPSTOL1 from African rice (Oryza glaberrima Steud) and its distribution in the genus Oryza. Theor Appl Genet. 2014;127:1387–98. doi: 10.1007/s00122-014-2306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Q, Zheng X, Luo J, Gaut BS, Ge S. Multilocus analysis of nucleotide variation of Oryza sativa and its wild relatives: Severe bottleneck during domestication of rice. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:875–88. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukherjee A, Sarkar S, Chakraborty AS, Yelne R, Kavishetty V, Biswas T, Mandal N, Bhattacharyya S. Phosphate acquisition efficiency and phosphate starvation tolerance locus (PSTOL1) in rice. J Genet. 2014;93:683–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Sarkar S, Yelne R, Chatterjee M, Das P, Debnath S, Chakraborty A, Mandal N, Bhattacharya K, Bhattacharyya S. Screening for phosphorus(P) tolerance and validation of Pup-1 linked markers in indica rice. Indian J Genet Plant Breed. 2011;71:209–13.

- 28.Wissuwa M, Wegner J, Ae N, Yano M. Substitution mapping of Pup1: a major QTL increasing phosphorus uptake of rice from a phosphorus-deficient soil. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;105:890–7. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hufnagel B, de Sousa SM, Assis L, Guimaraes CT, Leiser W, Azevedo GC, Negri B, Larson BG, Shaff JE, Pastina MM, Barros BA, Weltzien E, Rattunde HFW, Viana JH, Clark RT, Falcão A, Gazaffi R, Garcia AAF, Schaffert RE, Kochian L V, Magalhaes J V. Duplicate and conquer: multiple homologs of PHOSPHORUS-STARVATION TOLERANCE1 enhance phosphorus acquisition and sorghum performance on low-phosphorus soils. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:659–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Azevedo GC, Cheavegatti-Gianotto A, Negri BF, Hufnagel B, E Silva L d C, Magalhaes JV, Garcia AAF, Lana UGP, de Sousa SM, Guimaraes CT. Multiple interval QTL mapping and searching for PSTOL1 homologs associated with root morphology, biomass accumulation and phosphorus content in maize seedlings under low-P. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wissuwa M, Ae N. Further characterization of two QTLs that increase phosphorus uptake of rice (Oryza sativa L.) under phosphorus deficiency. Plant Soil. 2001;237:275–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1013385620875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delph LF, Kelly JK. On the importance of balancing selection in plants. New Phytol. 2014;201:45–56. doi: 10.1111/nph.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castric V, Vekemans X. Plant self-incompatibility in natural populations: A critical assessment of recent theoretical and empirical advances. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:2873–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mboup M, Fischer I, Lainer H, Stephan W. Trans-species polymorphism and allele-specific expression in the CBF gene family of wild tomatoes. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:3641–52. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cork JM, Purugganan MD. High-diversity genes in the Arabidopsis genome. Genetics. 2005;170:1897–911. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gross BL, Skare KJ, Olsen KM. Novel Phr1 mutations and the evolution of phenol reaction variation in US weedy rice (Oryza sativa) New Phytol. 2009;184:842–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida S, Forno DA, Cock JH, Gomez KA. Laboratory manual for physiological studies of rice. 3rd edition. Los Banos (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute; 1976. p. 83.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets supporting the results in this article are available in Genbank, KU922566 - KU922725.