Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine agreement between self-reported and medically recorded self-harm, and investigate whether the prevalence of self-harm differs in questionnaire responders vs. non-responders. A total of 4,810 participants from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) completed a self-harm questionnaire at age 16 years. Data from consenting participants were linked to medical records (number available for analyses ranges from 205–3,027). The prevalence of self-harm leading to hospital admission was somewhat higher in questionnaire non-responders than responders (2.0 vs. 1.2%). Hospital attendance with self-harm was under-reported on the questionnaire. One third reported self-harm inconsistently over time; inconsistent reporters were less likely to have depression and fewer had self-harmed with suicidal intent. Self-harm prevalence estimates derived from self-report may be underestimated; more accurate figures may come from combining data from multiple sources.

Keywords: agreement, ALSPAC, consistency, data linkage, self-harm, suicide attempt

INTRODUCTION

Community studies of self-harm are vital as the majority of self-harm episodes do not present to clinical services (Hawton, Rodham, Evans, & Weatherall, 2002; Kidger, Heron, Lewis, Evans, & Gunnell, 2012; Ystgaard et al., 2009). However, such studies are subject to a number of limitations such as misreporting and non-response (Grimes & Schulz, 2002), which can lead to bias in estimates of prevalence and measures of association. The extent to which this occurs in the case of self-harm is not currently known.

Non-response and loss to follow-up occur more frequently among individuals with particular characteristics (Kidger et al., 2012; Wolke et al., 2009). For example, in the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology Study (Christl, Wittchen, Pfister, Lieb, & Bronisch, 2006), participation rates at follow-up were lower among those who had attempted suicide compared to those without suicidal thoughts or attempts. This skewed pattern of participation would have led to underestimates of the prevalence of suicide attempts.

In addition, as information on self-harm is typically collected retrospectively via self-report, the accuracy of responses may be affected by issues such as denial, reinterpretation, problems with recall, current mood, or by misinterpretation of the study questions (Velting, Rathus, & Asnis, 1998). There is also evidence to suggest that concerns over social desirability may encourage under-reporting, as adolescents have been found to report suicide attempts two to three times more frequently under conditions of anonymity (Safer, 1997).

The agreement between different sources of data on self-reported self-harm in adolescents has previously been investigated (Bjärehed, Pettersson, Wångby-Lundh, & Lundh, 2013; O'Sullivan & Fitzgerald, 1998; Ougrin & Boege, 2013; Ross & Heath, 2002; Velting et al., 1998). Most have focused on suicide attempts, which comprise only a portion of episodes (Hawton et al., 2002; Kidger et al., 2012; Muehlenkamp & Gutierrez, 2004). Studies have reported inconsistency across different self-report methods, e.g., interviews vs. questionnaires (Bjärehed et al., 2013; O'Sullivan & Fitzgerald, 1998; Ougrin & Boege, 2013; Ross & Heath, 2002; Velting et al., 1998), and also when using the same self-report method across repeated assessments (Christl et al., 2006; Hart, Musci, Ialongo, Ballard, & Wilcox, 2013). However, the absence of a gold standard means it is not possible to tell which measure/assessment is more accurate (see Table 1 for a summary of studies). There is some evidence to suggest that individuals with more severe psychopathology are more likely to report self-harm consistently over time (Christl et al., 2006; Eikelenboom, Smit, Beekman, Kerkhof, & Penninx, 2014).

TABLE 1. Studies Investigating Consistency in Self-Harm Reports: Across Different Measures or Over Time.

| Publication | Country | Sample | Measure | Comparison of different measures | Consistency in reports over time | Other design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent samples | |||||||

| Ougrin and Boege (2013) | United Kingdom | Adolescent inpatients and outpatients n = 100, 12–17 years |

Self-harm | Yes Self-report questionnaire and clinical record (reported during the clinical assessment) |

No | No | 3 (3%) indicated in the clinical record they had self-harmed but did not report self-harm on the questionnaire. 20 (20%) reported at least one episode of self-harm on the questionnaire that was not recorded in the clinical record |

| Hart et al. (2013) | United States | Longitudinal community sample of adolescents n = 678, Assessed annually between age 12 and 22 years |

Suicide attempts | No | Yes Also examined characteristics associated with discrepant reporting |

No | 88.5% inconsistently reported a suicide attempt at some point during the study; 65.3% were inconsistent the year following the self-harm event Consistent and inconsistent reporters did not differ on clinical or demographic variables, but consistent reporters had higher lifetime suicidal ideation |

| Bjärehed et al. (2013) | Sweden | Adolescent community sample n = 1,052, from grade 7 (mean age 13.7 years) and 8 (mean age 14.7 years) |

Non-suicidal self-injury | Yes Self-report questionnaire and follow-up interview |

No | No | 97 adolescents were selected for interview. 32/66 (48%) participants who reported self-harm on the questionnaire did not disclose self-harm during the follow-up interview. |

| Kidger et al. (2012) | United Kingdom | Adolescent community sample n = 4810, 16 years |

Suicide attempts | No | No | Yes Examined suicidal thoughts among those with suicidal self-harm |

Approximately 10% of those who reported wanting to die during the most recent episode of self-harm said they had never had thoughts of killing themselves |

| Christl et al. (2006) | Germany | Longitudinal community sample of adolescents/young adults n = 3021, 14–24 years at baseline |

Suicide attempts | No | Yes Also examined characteristics associated with discrepant reporting |

Yes Compared drop-out rates among those with and without suicidal behaviour |

One third of baseline suicide attempters (n = 15/45), did not report a suicide attempt at follow-up 4 years later 81% of discrepant reporters were female and 59% were aged 14–17 at baseline. Greater consistency in reporting was associated with a higher number of psychiatric disorders Those with a suicide attempt at baseline were at least 1.6 times more likely to drop out of the study then those without suicide attempts or ideas |

| Ross and Heath (2002) | Not specified | Adolescent community sample n = 440 (from 2 schools), average age 14–15 years |

Self-mutilation (defined as deliberate alteration or destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent) | Yes Self-report screening questionnaire and follow-up interview |

No | No | School sample 1: 38.8% who reported self-harm on the questionnaire were not classified as having self-harmed following the interview (19/49) School sample 2: 24.4% who reported self-harm on the questionnaire were not classified as having self-harmed following the interview (10/41) |

| Velting et al. (1998) | United States | Adolescent outpatients n = 48, 12–20 years, mean 15.3 years |

Suicide attempts | Yes Self-report questionnaire and interview Also investigated explanations and characteristics associated with discrepant reporting |

No | No | Discrepancies in reporting were found amongst 50% of the sample (24/48). Discrepancies primarily due to confusion with the operational definition of suicidal behaviour (i.e., confused attempt and ideation or confused attempt and gesture). The discrepant and non-discrepant groups were comparable on measures of suicidal intent, ideation, and hopelessness and on their diagnostic profiles |

| O'Sullivan and Fitzgerald (1998) | Ireland | Adolescent community sample n = 88 age 13–14 years |

Suicide attempt | Yes Self-report screening questionnaire and follow-up interview |

No | No | 45 adolescents completed a follow-up interview. 5/7 (71%) participants who reported a suicide attempt on the questionnaire did not disclose self-harm during the follow-up interview. |

| Adult samples | |||||||

| Eikelenboom et al. (2014) | The Netherlands | Longitudinal cohort of adults with depressive or anxiety disorders n = 1973, aged 18–65 years at baseline, (mean age 42.4 years) |

Suicide attempts | No | Yes Also examined characteristics associated with discrepant reporting |

No | 23% of baseline suicide attempters, did not report their attempt at follow-up 2 years later (63/274) Consistent reporting was associated with a greater number of suicide attempts, and more severe current psychopathology. No differences were found for recency of the event, age, sex, or education |

| Morthorst et al. (2011) | Denmark | Patients admitted to hospital following a suicide attempt n = 243, age 12+, mean age 31 years |

Suicide attempts, assessed 1 year after baseline | Yes Self-report (telephone interview) and hospital records |

No | No | Seven suicide attempts listed in the hospital records were not reported by participants. Nine patients reported a suicide attempt that was not listed in the hospital records |

| Plöderl et al. (2011) | Austria | Adult community sample n = 1385, age 18–84 years, Mean 37.8 years |

Suicide attempts | No | No | Yes Examined intent to die among those reporting suicidal self-harm |

One quarter (15/60) of individuals reporting a suicide attempt were false positives (lacked intent or attempt aborted) 0.8% (n = 11) were identified as false negatives (reported no suicide attempt on the screen question but reported a self-harm event with intent to die in follow-up questions). 2/11 (18%) false negatives resulted in injuries requiring hospital treatment There were no differences between true positives and false positives regarding age or education or lethality of method |

| Linehan et al. (2006) | United States | Adult clinical sample: Five cohorts, three with borderline personality disorder | Self-harm | Yes Self-report interview and 1) therapist notes 2) participant diary cards 3) medical records |

No | No | Agreement with therapist notes (presence/absence of self-harm) was 83% Good agreement with diary cards (mean 4.5 acts at interview vs. mean 4.3 acts on diary cards) 82% of episodes reported by participants as being medically treated had a corresponding medical record. There were no false negatives —all medically treated episodes were reported by participants. |

| Nock and Kessler (2006) | United States | Predominately Adult community sample n = 5,877, aged 15–54 years |

Suicide attempts | No | No | Yes Examined intent to die among those reporting suicidal self-harm |

112/268 (42%) of those reporting a lifetime history of suicide attempt reported no intent to die |

Whereas previous studies have typically compared self-report questionnaire and interview responses, the present study compares self-reported self-harm with data from medical records. This data is external and objective, although it cannot be considered to be free from error. We linked data from medical records with data reported by participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a longitudinal population-based birth cohort (Boyd et al., 2013). Our aims were to:

Investigate whether the prevalence of self-harm recorded in medical records differs between responders and non-responders to the self-harm questionnaire.

Investigate the level of agreement between self-report and medically recorded self-harm events.

Examine consistency in the reporting of self-harm in ALSPAC over time, by comparing questionnaire responses at age 16 and 18 years.

Identify characteristics associated with inconsistent reporting of self-harm over time.

We hypothesize that the prevalence of self-harm recorded in medical records will be higher among questionnaire non-responders than responders, and that recall of self-harm episodes over time will be most consistent in individuals with more severe mental health problems/self-harm.

METHODS

Sample

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)

ALSPAC is a population-based birth cohort study examining influences on health and development across the lifecourse. The ALSPAC core enrolled sample consists of 14,541 pregnant women resident in the former county of Avon in South West England (United Kingdom), with expected delivery dates between April 1, 1991 and December 31, 1992 (Boyd et al., 2013). Of the 14,062 live births, 13,798 were singletons/first-born of twins and were alive at 1 year of age. Participants have been followed up since recruitment through regular questionnaires and research clinics. Detailed information about ALSPAC is available on the study website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac), which includes a fully searchable data-dictionary of available data (http://www.bris.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/data-access/data-dictionary). Self-harm was assessed via self-report questionnaire at age 16 years (mean age of respondents 16 years 8 months, standard deviation [SD] approximately 3 months). The postal questionnaire was sent to 9,383 participants of whom 4,855 (51.7%) returned it and 4,810 completed the self-harm items (Kidger et al., 2012). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Law and Ethics committee and local research ethics committees (NHS Haydock REC: 10/H1010/70).

Linkage

The Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) linked ALSPAC participants with the NHS Central Register, with a 99% match rate (Boyd et al., 2013); this was done on the basis of NHS ID number, name, date of birth, and postcode using deterministic linkage.

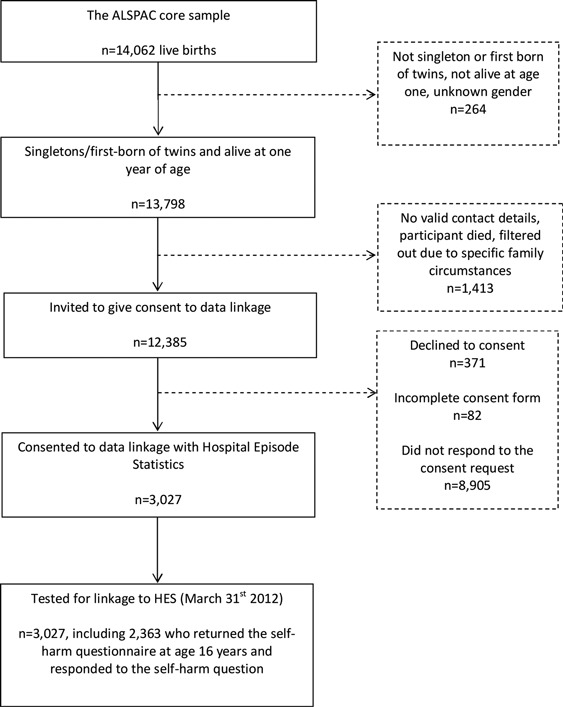

When the ALSPAC children reached adulthood (age 18), they were invited to enroll in the study in their own right and to consent to the extraction and use of their health records. Through the Project to Enhance ALSPAC through Record Linkage (PEARL) http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/participants/playingyourpart/ information and consent forms were posted to 12,385 of the participants eligible to be included in this investigation (singletons/first born twins from the ALSPAC core enrolled sample who were alive at 1 year. See Figure 1). Of those invited to consent (n = 12,385), 3,027 (24.4%) consented to data linkage by the study cut-off date, 8,905 (71.9%) did not respond to the consent request, and 82 (0.7%) returned an incomplete consent form. Only 371 (3.0%) declined to consent.

FIGURE 1.

Flow-chart of linkage between the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) birth cohort and the Hospital Episode Statistics database (HES).

The Hospital Episode Statistics Database (HES)

The HES database (Copyright © 2012, re-used with the permission of The Health and Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved) contains information about hospital presentations and admissions for all NHS hospitals in England; it contains admissions data from 1989 onwards, outpatient data from 2003 onwards and A&E data from 2007 onwards (http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes). Of the 3,027 individuals who consented to data linkage (see above) 2,957 individuals (97.7%) had an existing linkage to the NHS central register, which in turn provided a means to identify the individuals’ secondary care records contained in the HES database. The remaining 70 cases were linked to HES using NHS ID number, name, and date of birth. In this scenario “linkage” refers to the process of testing if the ALSPAC participants had any HES records rather than the actual identification and extraction of a record. We make this distinction as some individuals will genuinely not have any HES records, while others may have a HES record which we failed to identify during the linkage process. In March 2013 the NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) extracted the hospital admissions records of 2,988 participants, although we consider the denominator to be the 3,027 cases tested for linkage.

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD)

The CPRD is an anonymized database of primary care records of around 5 million (∼8%) patients in the UK. Linkage between ALSPAC and the CPRD was conducted by the NHS Information Centre (NHS IC) as a trusted third party. With approval from the NIGB Ethics and Confidentiality Committee, the NHS IC identified ALSPAC eligible individuals who also appeared in the CPRD, and sent an anonymized linking dataset to be stored securely at the CPRD where the data were merged and analyzed. This particular linkage does not require consent above and beyond the consent obtained for participation in ALSPAC. However, any participants who did not agree to their health records being extracted (via the PEARL consent request described above) were excluded (n = 3).

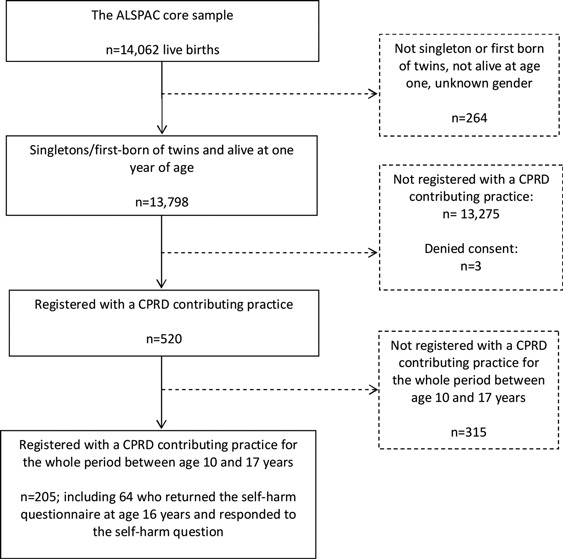

Of the live births linked by the NHS IC that appeared in the CPRD, 520 were in the sub-sample eligible for this investigation (singletons/first born twins from the ALSPAC core enrolled sample who were alive at 1 year). The sample was further restricted to individuals who were registered with a CPRD-contributing practice for the entire period between age 10 and 17 years (n = 205) (Figure 2), to ensure that there were no breaks in the patients’ records. We did not examine CPRD records before the age of 10 years, as self-harm before this age is rare.

FIGURE 2.

Flow-chart of linkage between the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) birth cohort and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD).

Measures

History of self-harm was assessed in the ALSPAC cohort, the Hospital Episode Statistics Database (Secondary Care) and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (Primary Care). The methods of assessment for each data source are described below. Data on psychosocial characteristics were also collected in ALSPAC.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)

The self-harm questions used in the age 16 self-report questionnaire were based on those used in the CASE study (Madge et al., 2008). Participants who responded positively to the item “have you ever hurt yourself on purpose in any way (e.g., by taking an overdose of pills or by cutting yourself)?” were classified as having a lifetime history of self-harm.

Those who answered “yes” to having self-harmed were then asked further closed response questions, including how long ago they last hurt themselves (in the last week, more than a week ago but in the last year, more than a year ago), the reasons for self-harm the last time they hurt themselves on purpose (six response categories), and whether they had ever seriously wanted to kill themselves when self-harming (Kidger et al., 2012). Participants were classified as having a lifetime history of suicidal self-harm if they selected “I wanted to die” as a reason for harming themselves on the most recent occasion, or if they reported they had ever seriously wanted to kill themselves when self-harming (Mars et al., 2014).

The same question was used to assess lifetime self-harm at age 18 years, using the self-administered computerized version of the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R) (Lewis, Pelosi, Araya, & Dunn, 1992). There is close agreement between the self-administered computerized version and the interviewer administrated versions of the CIS-R (Bell, Watson, Sharp, Lyons, & Lewis, 2005; Lewis, 1994; Patton et al., 1999).

Psychosocial Characteristics

We examined key psychosocial characteristics assessed previously in ALSPAC to identify factors associated with inconsistencies in reporting self-harm over time. The following variables were used: (1) participant's gender, (2) ethnicity, (3) parent social class (professional/managerial or other occupations; the highest of maternal or paternal social class was used), (4) highest maternal educational attainment (less than O-level, O-level, A-level, or university degree) measured during pregnancy (O-levels and A-levels are school qualifications taken around age 16 and 18 years respectively), (5) child IQ assessed using the Wechsler intelligence test for children (WISC-III) (Wechsler, 1991) at age 8 years (6) depression symptoms, assessed at age 16 and 18 years using the short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ), a score of 11 or more on the SMFQ was taken as indicative of depressive symptoms (Patton et al., 2008) and (7) depressive disorder, assessed at age 18 years using the CIS-R.

The Hospital Episode Statistics Database (HES)

We used an extract of the HES data including hospital admissions for self-harm (ICD 10 codes Y10–Y34, X60–X84 and X40–X49), A&E attendances for self-harm (A&E diagnostic codes 141/142 “poisoning (inc overdose) due to prescriptive/proprietary drugs,” or reason for A&E attendance coded as “deliberate self-harm”) and hospital admissions for a mental health condition(s) (ICD-10 codes F00–F99). Further details can be found in Appendix 1. While X40–X49 are coded as accidental poisoning, previous studies indicate that they are also used for self-harm. The date of hospital attendance was cross-referenced with the date of questionnaire completion to identify whether events occurred before or after completion of the self-harm questionnaire. Although A&E data is recorded in HES, it is only available from 2007 onwards and is likely to be under-reported. For example, in the extracted data, all but two self-harm hospital admissions were recorded as having come via A&E (the remaining two admissions were emergency referrals by GP); however, two-thirds of hospital admissions had no corresponding A&E record for self-harm. For this reason, we have focused primarily on hospital admissions data in this paper, as this is known to be more complete. The findings for A&E only data are also presented, but need to be interpreted with caution.

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD)

Cases of self-harm occurring in the CPRD until December 31, 2011 were identified using appropriate Read codes for attempted suicide and self-harm (see Appendix 2) (Thomas et al., 2013).

Analysis Plan

Non-Response

We examined whether there was an association between questionnaire response and medically recorded self-harm by comparing the prevalence of self-harm in HES and the CPRD among those who completed and did not complete the self-harm questionnaire at age 16 years.

Agreement Between Self-Report and Medically Recorded Self-Harm Events

We compared self-reported self-harm episodes with events recorded in HES and the CPRD, in order to identify instances in which self-harm was inconsistently reported.

Consistency in Self-Report Over Time

We investigated inconsistency in reporting of lifetime self-harm over time between age 16 and 18 years in ALSPAC cohort. Participants who reported no self-harm, or reported self-harm for the first time at age 18 years were excluded from these analyses.

Characteristics associated with inconsistent reporting of self-harm over time were also examined using logistic regression.

RESULTS

Self-Harm

HES

Of the 3,027 ALSPAC participants tested for linkage with HES (hospital records), 54 (1.8%) had one or more self-harm events recorded in HES, including 41 participants with at least one recorded hospital admission for self-harm, and 18 (0.6%) with at least one recorded “A&E only” attendance for self-harm (i.e., A&E attendance without subsequent hospital admission). It is notable that 66% of individuals who were admitted to hospital following self-harm had no corresponding A&E record for self-harm. Eighty-two (2.7%) had at least one hospital admission for a mental health condition recorded in HES. Of the 3,027 individuals tested for linkage, 2,363 (78.1%) completed the self-harm questionnaire at age 16 years.

CPRD

Of the 205 ALSPAC participants registered with a CPRD contributing practice between age 10 and 17 years, 64 (31.2%) completed the self-harm questionnaire at age 16 years. Only 6 participants (2.9%) had a relevant self-harm Read code recorded in the CPRD.

Non-Response

HES

The prevalence of hospital admissions for self-harm and mental health conditions recorded in HES was higher among those who did not complete the self-harm questionnaire at age 16 years than among those who did (Table 2) (self-harm hospital admissions: 2.0% in non-responders vs. 1.2% in responders, difference = 0.8%, 95% CI −0.4–1.9%, P = 0.128; mental health hospital admissions 4.8 vs. 2.1%, difference = 2.7%, 95% CI 1.0–4.4%, P < 0.001). The same pattern of results was found for A&E only self-harm attendances (1.1 vs. 0.5%, difference =0.6%, 95% CI −0.2–1.4%, P = 0.081).

TABLE 2. Differences In Prevalence of Hospital Admissions For Self-Harm and Mental Health Conditions in the Hospital Episode Statistics Database Among Those Who Completed vs. Those Who Did Not Complete the Age 16 Year Self-Harm Questionnaire.

| Self-harm questionnaire data n = 2,363 N (%) | No self-harm questionnaire data n = 664 N (%) | Difference (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admitted to hospital for self-harm | 28 (1.2%) | 13 (2.0%) | 0.8% (−0.4%, 1.9%) | 0.128 |

| Admitted to hospital for mental health problem | 50 (2.1%) | 32 (4.8%) | 2.7% (1.0%, 4.4%) | <0.001 |

CPRD

Two of the 6 individuals with a self-harm Read code recorded in the CPRD completed the age 16 self-harm questionnaire. There was no evidence of a difference in prevalence between questionnaire responders and non-responders (2.8% in non-responders vs. 3.1% in responders, difference = 0.3%, 95% CI −4.8–5.4%, P = 0.910). These findings need to be interpreted with caution, given the small number of ALSPAC individuals with a self-harm Read code recorded in the CPRD (n = 6).

Agreement Between Self-Report and Medical Records

HES

Of the 2,363 individuals tested for linkage who completed the self-harm questionnaire at age 16 years, 419 (17.7%) reported a history of self-harm. Only 12 (2.9%; 95% CI 1.5–5.9%) of these episodes were recorded in HES.

There were 15 self-harm hospital attendances recorded in HES prior to completion of the self-harm questionnaire (12 admissions and 3 A&E only attendances). Three (20%; 95% CI 4–48%) of these episodes were not reported by ALSPAC participants on the questionnaire (1/12 admissions and 2/3 A&E only attendances).

CPRD

Both of the self-harm events recorded in the CPRD were reported by participants on the self-harm questionnaire; however, neither participant reported having sought help for self-harm from their GP (a consultation with the GP would be necessary in order for a self-harm Read code to be recorded in the CPRD).

Consistency of Reporting of Self-Harm Over Time

Five hundred and eighty nine individuals reported lifetime self-harm at age 16 years and provided information on self-harm at age 18 years. Of these, 385 (65.4%) reported self-harm consistently at both time points, and 204 individuals (34.6%) reported self-harm inconsistently, i.e., reported lifetime self-harm at age 16 years but not at age 18 years.

Characteristics Associated With Consistency in Reporting of Self-Harm Over Time

Compared with those who reported self-harm consistently over time, those who reported self-harm inconsistently were less likely to have evidence of depression at age 16 and 18 years, were less likely to have self-harmed in the year prior to the age 16 year questionnaire, and were less likely to have harmed with suicidal intent by age 16 years (Table 3). There was little evidence for differences according to gender, social class, IQ, maternal education or ethnicity (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Psychosocial Characteristics Associated With Inconsistent Reporting of Self-Harm Episodes Over Time.

| Self-harm reported consistently (n = 385) | Self-harm reported inconsistently (n = 204) | OR [95%CI] | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, n (%) | 312 (81.0%) | 162 (79.4%) | 0.90 [0.59, 1.38] | 0.636 |

| Parental social class, (pregnancy), n (%) | ||||

| Other | 131 (36.1%) | 62 (32.5%) | ||

| Professional/managerial | 232 (63.9%) | 129 (67.5%) | 0.85 [0.59, 1.23] | 0.395 |

| Mother's education (pregnancy), n (%)a | ||||

| <O-level | 60 (15.9%) | 29 (14.6%) | ||

| O-level | 141 (37.4%) | 69 (35.2%) | ||

| Degree/A level | 176 (46.7%) | 100 (50.2%) | 0.91 [0.72, 1.16] | 0.441 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 361 (96.8%) | 190 (96.5%) | ||

| Non-white | 12 (3.2%) | 7 (3.5%) | 0.90 [0.34, 2.33] | 0.832 |

| IQ, age 8 years, mean (SD) | 108.7 (15.6) | 110.6 (14.5) | 1.01 [1.00, 1.02] | 0.166 |

| Depression symptoms: SMFQ score 11+, age 16 years, n (%) | 167 (44.2%) | 62 (30.7%) | 0.56 [0.39, 0.80] | 0.002 |

| Depression symptoms: SMFQ score 11+, age 18 years, n (%) | 159 (46.4%) | 59 (31.1%) | 0.52 [0.36, 0.76] | 0.001 |

| Depressive disorder: CIS-R, age 18 years | 83 (21.6%) | 15 (7.4%) | 0.29 [0.16, 0.52] | <0.001 |

| Past year self-harm, age 16 years | 237 (61.9%) | 99 (49.3%) | 0.60 [0.42, 0.84] | 0.003 |

| Lifetime self-harm with suicidal intent, age 16 years | 154 (40.2%) | 42 (20.9%) | 0.39 [0.26, 0.58] | <0.001 |

Note. SMFQ: Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; CIS-R: Clinical Interview Schedule revised.

aOR for maternal education assumes a linear trend across the education categories.

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

This study is, as far as we are aware, the first to examine whether the prevalence of medically recorded self-harm differs from prevalence determined by questionnaire response in a community-based sample of adolescents. We also investigated the level of agreement between self-reported self-harm history and data obtained from medical records.

We found some evidence for both selective non-participation of individuals with self-harm, and for discrepancies between self-reported and medically recorded self-harm episodes; approximately one-fifth of self-harm events recorded in HES (hospital admissions or A&E presentations) were not reported by participants on the questionnaire. Taken together, these findings suggest that prevalence estimates derived from self-report may underestimate the true rate of adolescent self-harm in the community.

We additionally examined the consistency of self-reported self-harm over time and found that over a third of respondents who reported self-harm at age 16 years said they had never self-harmed when asked at age 18 years. Those who reported self-harm inconsistently over time were less likely to have to have depressive disorder, less likely to have harmed in the year prior to the age 16 year questionnaire and were less likely to have self-harmed with suicidal intent.

Strengths and Limitations

ALSPAC is a large, population-based study, which is important, given that less than 20% of adolescents who self-harm present to medical services (Hawton et al., 2002; Kidger et al., 2012). We investigated the level of agreement in reports of self-harm both across different sources (self-report and medical records) and over time.

The findings need to be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, we were only able to compare reports among those who had been admitted to hospital or had consulted with their GP. We were also only able to examine self-harm hospital admissions among those who had consented to data linkage (24% of the sub-sample invited to consent) and GP events for those in the CPRD between age 10 and 17 years (1.5% of the sub-sample of 13,798 included in this investigation). These sub samples with available linked records may not be representative of the whole ALSPAC cohort. The issue of required consent has the potential to induce bias in our findings, however using questionnaire data we found little evidence of an association between self-harm and consent to data linkage and so this is unlikely to be a problem in this study. Second, it is likely that cultural differences influence self-reporting of self-harm. The degree of stigma associated with mental illness and self-harm varies around the world (Abdullah & Brown, 2011; Evans-Lacko, Brohan, Mojtabai, & Thornicroft, 2012; Reynders, Kerkhof, Molenberghs, & Van Audenhove, 2014), therefore findings from our study may not be generalizable outside a UK context.

Third, the number of individuals with self-harm recorded in their medical records was small, particularly in the CPRD. This precluded our ability to examine characteristics associated with inconsistent reporting, and limited power to detect differences between questionnaire responders and non-responders. Findings therefore need to be interpreted with caution, and require replication in a larger sample. It is possible that some episodes of self-harm may not have been recorded in the CPRD (Thomas et al., 2013), or may have been missed (i.e., if documented as a free text response rather than a Read code). Fourth, when extracting data from the HES database, we included codes related to accidental poisoning (ICD 10 codes X40–X49) as these codes are often used to indicate self-harm. While some may be true instances of accidental self-poisoning, this is unusual in adolescence.

Finally, self-harm in ALSPAC was assessed via self-report questionnaire at age 16 years and via a self-administered computerized assessment at age 18 years. Although the question used at both time points was identical, the difference in setting may have contributed to the discrepancies in reporting found in this study.

Comparison With Previous Research

Previous studies investigating inconsistency in reporting of self-harm have typically relied on comparisons between interview and questionnaire responses (Bjärehed et al., 2013; Ougrin & Boege, 2013; Ross & Heath, 2002; Velting et al., 1998). Lower rates of self-harm are usually found when using interview as opposed to questionnaire measures (Evans, Hawton, Rodham, Psychol, & Deeks, 2005). However, the absence of a gold standard assessment for self-harm means that it is not possible to identify which of these measurement approaches is more accurate—the ability to ask additional clarification questions could help to eliminate false positives that arise from inaccurate self-reports (Hawton et al., 2002; Ross & Heath, 2002; Velting et al., 1998), but it is also possible that the loss of anonymity found with interview assessments may result in under-reporting of self-harm (Safer, 1997).

In the Early Developmental stages of Psychopathology Study, Christl et al. (2006) found some evidence for selective non-response as those who reported suicide attempts at baseline were at least 1.6 times more likely to drop out of the study than those without suicidal thoughts or behavior. The use of data linkage allows us to extend this work by objectively comparing the prevalence of self-harm among questionnaire responders and non-responders. There was also some evidence for inconsistency between self-reported and medically recorded self-harm. Possible reasons for discrepancies include concerns over stigma, denial, or problems with recall. Individuals may also suppress painful memories such as self-harm or suicidal ideation, which has been suggested as a possible adaptive defensive mechanism (Goldney, Winefield, Winefield, & Saebel, 2009; Klimes-Dougan, Safer, Ronsaville, Tinsley, & Harris, 2007).

Our finding that a third of adolescents were discrepant in their reporting of lifetime self-harm over time is lower than the proportion found by Hart et al. (2013) (approximately two thirds disrepant 1 year after reporting a self-harm event) but similar to findings of other previous longitudinal research (Eikelenboom et al., 2014, Christl et al., 2006), all of which investigated reporting of suicide attempts. Inconsistent reporting has also been shown for other stigmatized behaviors such as drug use (Percy, McAlister, Higgins, McCrystal, & Thornton, 2005). We extend this research by examining consistency in reporting of self-harm regardless of suicidal intent, and by examining various characteristics associated with discrepant reporting. Similar to Christl et al. (2006) and Eikelenboom et al. (2014), we found greater consistency in reporting among those with psychopathology. We also found individuals were more likely to report self-harm consistently if they had harmed with suicidal intent during their lifetime, and if they had self-harmed in the year prior to questionnaire completion. This could suggest that more severe self-harm episodes and those that are more recent are more likely to be recalled by participants and may be less subject to reinterpretation. However, in their investigation of suicide attempts in adults, Eikelenboom et al. (2014) found no association between consistency in reporting and the recency of self-harm at baseline. It is also possible that individuals with psychopathology and those who have harmed with suicidal intent may be more likely to continue to self-harm as adults. The reasons for discrepant reporting require further investigation and could include denial, errors in recall, or reinterpretation of the self-harm event. Reports may also be influenced by current mood state, for example depressed mood could lead to enhanced recall of negative events, such as self-harm. Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine in this, or other studies, which of the assessments is more accurate (i.e., whether the first reporting of self-harm is a false positive or whether the second reporting is a false negative).

It is also important to note that while selective non-participation of those with self-harm and inconsistent reporting could result in distorted prevalence estimates, this does not necessarily lead to biased estimates of associations between self-harm and exposure variables (Wolke et al., 2009). Further research is planned to investigate this issue in more detail within the ALSPAC cohort.

CONCLUSION

In our analyses of the ALSPAC cohort, we have shown that self-harm prevalence estimates derived from self-report are affected by non-response and inconsistent reporting, and likely underestimate the true level of adolescent self-harm in the community. Our findings require replication, but suggest benefits of combining self-report self-harm data with data from medical records. To maximize the potential for this approach would require complete coverage of medical records for the sample in question. In practice achieving this may be restricted by governance requirements based on concerns around the protection of privacy with regard to sensitive information in the situation where individuals have not provided explicit consent. Such concerns may be offset by evidence that data-linkage as we describe here can improve the validity of medical research and thus enhance the potential of research to improve the public good.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no conflict of interests

Biographies

Becky Mars, Rosie Cornish, Jon Heron, Andy Boyd, Catherine Crane, Keith Hawton, Glyn Lewis, Kate Tilling, John Macleod, and David Gunnell

Rosie Cornish, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Jon Heron, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Andy Boyd, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Catherine Crane, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Keith Hawton, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Glyn Lewis, Mental Health Sciences Unit, University College London, London, UK.

Kate Tilling, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

John Macleod, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

David Gunnell, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

APPENDIX 1

List of. ICD-10 Codes Used to Identify Hospital Admissions for Non-fatal Self-harm in the Hospital Episodes Statistics database (HES).

| ICD-10 code | Description |

|---|---|

| X40 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics |

| X41 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, antiparkinsonism and psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified |

| X42 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics [hallucinogens], not elsewhere classified |

| X43 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other drugs acting on the autonomic nervous system |

| X44 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances |

| X45 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to alcohol |

| X46 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to organic solvents and halogenated hydrocarbons and their vapors |

| X47 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapors |

| X48 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to pesticides |

| X49 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified chemicals and noxious substances |

| X60 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics |

| X61 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, antiparkinsonism and psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified |

| X62 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics [hallucinogens], not elsewhere classified |

| X63 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to other drugs acting on the autonomic nervous system |

| X64 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances |

| X65 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to alcohol |

| X66 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to organic solvents and halogenated hydrocarbons and their vapors |

| X67 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapors |

| X68 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to pesticides |

| X69 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified chemicals and noxious substances |

| X70 | Intentional self-harm by hanging, strangulation and suffocation |

| X71 | Intentional self-harm by drowning and submersion |

| X72 | Intentional self-harm by handgun discharge |

| X73 | Intentional self-harm by rifle, shotgun and larger firearm discharge |

| X74 | Intentional self-harm by other and unspecified firearm discharge |

| X75 | Intentional self-harm by explosive material |

| X76 | Intentional self-harm by smoke, fire and flames |

| X77 | Intentional self-harm by steam, hot vapors and hot objects |

| X78 | Intentional self-harm by sharp object |

| X79 | Intentional self-harm by blunt object |

| X80 | Intentional self-harm by jumping from a high place |

| ICD-10 code | Description |

| X81 | Intentional self-harm by jumping or lying before moving object |

| X82 | Intentional self-harm by crashing of motor vehicle |

| X83 | Intentional self-harm by other specified means |

| X84 | Intentional self-harm by unspecified means |

| Y10 | Poisoning by and exposure to nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics, undetermined intent |

| Y11 | Poisoning by and exposure to antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, antiparkinsonism and psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified, undetermined intent |

| Y12 | Poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics [hallucinogens], not elsewhere classified, undetermined intent |

| Y13 | Poisoning by and exposure to other drugs acting on the autonomic nervous system, undetermined intent |

| Y14 | Poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances, undetermined intent |

| Y15 | Poisoning by and exposure to alcohol, undetermined intent |

| Y16 | Poisoning by and exposure to organic solvents and halogenated hydrocarbons and their vapors, undetermined intent |

| Y17 | Poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapors, undetermined intent |

| Y18 | Poisoning by and exposure to pesticides, undetermined intent |

| Y19 | Poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified chemicals and noxious substances, undetermined intent |

| Y20 | Hanging, strangulation and suffocation, undetermined intent |

| Y21 | Drowning and submersion, undetermined intent |

| Y22 | Handgun discharge, undetermined intent |

| Y23 | Rifle, shotgun and larger firearm discharge, undetermined intent |

| Y24 | Other and unspecified firearm discharge, undetermined intent |

| Y25 | Contact with explosive material, undetermined intent |

| Y26 | Exposure to smoke, fire and flames, undetermined intent |

| Y27 | Contact with steam, hot vapors and hot objects, undetermined intent |

| Y28 | Contact with sharp object, undetermined intent |

| Y29 | Contact with blunt object, undetermined intent |

| Y30 | Falling, jumping, or pushed from a high place, undetermined intent |

| Y31 | Falling, lying, or running before or into moving object, undetermined intent |

| Y32 | Crashing of motor vehicle, undetermined intent |

| Y33 | Other specified events, undetermined intent |

| Y34 | Unspecified event, undetermined intent |

APPENDIX 2

List of. Read Codes Used to Identify Suicides and Non-fatal Self-harm in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD).

| Read code | Description |

|---|---|

| SL..14 | Overdose of biological substance |

| SL..15 | Overdose of drug |

| SLHz.00 | Drug and medicament poisoning not otherwise specified |

| TK..00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury |

| TK..11 | Cause of overdose—deliberate |

| TK..12 | Injury—self-inflicted |

| TK..13 | Poisoning—self-inflicted |

| TK..14 | Suicide and self-harm |

| TK..15 | Attempted suicide |

| TK..17 | Para-suicide |

| TK0.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by solid/liquid substances |

| TK00.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by analgesic/antipyretic |

| TK01.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by barbiturates |

| TK01000 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by amylobarbitone |

| TK01100 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by barbitone |

| TK01400 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by phenobarbitone |

| TK02.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by other sedatives/hypnotics |

| TK03.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning tranquillizer/psychotropic |

| TK04.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by other drugs/medicines |

| TK05.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by drug or medicine not otherwise specified |

| TK06.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by agricultural chemical |

| TK07.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by corrosive/caustic substance |

| TK0z.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by solid/liquid substance not otherwise specified |

| TK1.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by gases in domestic use |

| TK10.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by gas via pipeline |

| TK11.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by liquefied petrol gas |

| TK1y.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted poisoning by other utility gas |

| TK1z.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by domestic gases not otherwise specified |

| TK2.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by other gases and vapors |

| TK20.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by motor vehicle exhaust gas |

| TK21.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted poisoning by other carbon monoxide |

| TK2z.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted poisoning by gases and vapors not otherwise specified |

| TK3.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury by hang/strangulate/suffocate |

| TK30.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by hanging |

| TK31.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury by suffocation by plastic bag |

| TK3y.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury by other means than hang/strangle/suffocate |

| TK3z.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury by hang/strangle/suffocate not otherwise specified |

| TK4.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by drowning |

| TK5.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by firearms and explosives |

| TK51.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by shotgun |

| TK52.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by hunting rifle |

| TK54.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by other firearm |

| TK5z.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by firearms/explosives not otherwise specified |

| TK6.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by cutting and stabbing |

| TK60.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by cutting |

| TK60100 | Self-inflicted lacerations to wrist |

| TK60111 | Slashed wrists self-inflicted |

| TK61.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by stabbing |

| TK6z.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by cutting and stabbing not otherwise specified |

| TK7.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by jumping from high place |

| TK70.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury—jump from residential premises |

| TK71.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury—jump from other manmade structure |

| TK72.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury—jump from natural sites |

| TK7z.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury—jump from high place not otherwise specified |

| TKx.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by other means |

| TKx0.00 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury—jump/lie before moving object |

| TKx0000 | Suicide + self-inflicted injury—jumping before moving object |

| TKx1.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by burns or fire |

| TKx2.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by scald |

| TKx3.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by extremes of cold |

| TKx4.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by electrocution |

| TKx5.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by crashing motor vehicle |

| TKx6.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by crashing of aircraft |

| TKx7.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury caustic substance, excluding poison |

| TKxy.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by other specified means |

| TKxz.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury by other means not otherwise specified |

| TKy.00 | Late effects of self-inflicted injury |

| TKz.00 | Suicide and self-inflicted injury not otherwise specified |

| U2..00 | [X]Intentional self-harm |

| U2..11 | [X]Self-inflicted injury |

| U2..12 | [X]Injury—self-inflicted |

| U2..13 | [X]Suicide |

| U2..14 | [X]Attempted suicide |

| U2..15 | [X]Para-suicide |

| U20.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to noxious substances |

| U20.11 | [X]Deliberate drug overdose/other poisoning |

| U200.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to non-opioid analgesic |

| U200.11 | [X]Overdose—paracetamol |

| U200.12 | [X]Overdose—ibuprofen |

| U200.13 | [X]Overdose—aspirin |

| U200000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to non-opioid analgesic at home |

| U200100 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning non-opioid analgesic at residential institution |

| U200400 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning non-opioid analgesic in street/highway |

| U200500 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning non-opioid analgesic trade/service area |

| U200y00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning non-opioid analgesic other specified place |

| U200z00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning non-opioid analgesic unspecified place |

| U201.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to antiepileptic |

| U201000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to antiepileptic at home |

| U201z00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning antiepileptic unspecified place |

| U202.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to sedative hypnotic |

| U202.11 | [X]Overdose—sleeping tablets |

| U202.12 | [X]Overdose—diazepam |

| U202.13 | [X]Overdose—temazepam |

| U202.15 | [X]Overdose—nitrazepam |

| U202.16 | [X]Overdose—benzodiazepine |

| U202.17 | [X]Overdose—barbiturate |

| U202.18 | [X]Overdose—amobarbital |

| U202000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning /exposure to sedative hypnotic at home |

| U202400 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning sedative hypnotic in street/highway |

| U202y00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning sedative hypnotic other specified place |

| U202z00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning sedative hypnotic unspecified place |

| U204.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to psychotropic drug |

| U204.11 | [X]Overdose—antidepressant |

| U204.12 | [X]Overdose—amitriptyline |

| U204.13 | [X]Overdose—SSRI |

| U204000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning /exposure to psychotropic drug at home |

| U204100 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning psychotropic drug at residential institution |

| U204y00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning psychotropic drug other specified place |

| U204z00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning psychotropic drug unspecified place |

| U205000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to narcotic drug at home |

| U205y00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning narcotic drug other specified place |

| U205z00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning narcotic drug unspecified place |

| U206.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to hallucinogen |

| U206400 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning hallucinogen in street/highway |

| U207.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to other autonomic drug |

| U207000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to other autonomic drug at home |

| U207z00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning other autonomic drug unspecified place |

| U208.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to other/unspecified drug/medicament |

| U208400 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning other/unspecified drug/medication in street/highway |

| U208y00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning other/unspecified drug/medication other specified place |

| U208z00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning other/unspecified drug/medication unspecified place |

| U20A.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning organic solvent, halogen hydrocarbon |

| U20A.11 | [X]Self-poisoning from glue solvent |

| U20A000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning organic solvent, halogen hydrocarbon, home |

| U20A400 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning organic solvent, halogen hydrocarbon, in highway |

| U20Az00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning organic solvent, halogen hydrocarbon, unspecified place |

| U20B.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to other gas/vapor |

| U20B.11 | [X]Self carbon monoxide poisoning |

| U20B000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to other gas/vapor at home |

| U20B200 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning other gas/vapor school/public admin area |

| U20By00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning other gas/vapor other specified place |

| U20Bz00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning other gas/vapor unspecified place |

| U20C.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to pesticide |

| U20C.11 | [X]Self-poisoning with weedkiller |

| U20C.12 | [X]Self-poisoning with paraquat |

| U20C000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to pesticide at home |

| U20Cy00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning pesticide other specified place |

| U20y.00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to unspecified chemical |

| U20y000 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning/exposure to unspecified chemical at home |

| U20y200 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning unspecified chemical school/public admin area |

| U20yz00 | [X]Intentional self-poisoning unspecified chemical unspecified place |

| U21.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by hanging/strangulation/suffocation |

| U210.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by hanging/strangulation/suffocation at home |

| U211.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by hanging/strangulation/suffocation occurrence at residential institution |

| U21y.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by hanging/strangulation/suffocation other specified place |

| U21z.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by hanging/strangulation/suffocation unspecified place |

| U22.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by drowning and submersion |

| U221.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by drowning/submersion occurrence at residential institution |

| U22y.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by drowning/submersion occurrence at other specified place |

| U22z.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by drowning/submersion occurrence at unspecified place |

| U24.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by rifle shotgun/larger firearm discharge |

| U241.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by rifle shotgun/larger firearm discharge occurrence at residential institution |

| U242.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by rifle shotgun/larger firearm discharge in school/public admin area |

| U25.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by other/unspecified firearm discharge |

| U250.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm other/unspecified firearm discharge occurrence at home |

| U26.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by explosive material |

| U27.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by smoke, fire and flames |

| U270.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by smoke fire/flames occurrence at home |

| U274.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by smoke fire/flame occurrence in street/highway |

| U27z.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by smoke fire/flames occurrence in unspecified place |

| U28.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by steam hot vapors/hot objects |

| U280.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by steam hot vapors/hot objects occurrence at home |

| U28z.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by steam hot vapors/hot objects occurrence in unspecified place |

| U29.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by sharp object |

| U290.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by sharp object occurrence at home |

| U291.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by sharp object occurrence at residential institution |

| U294.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by sharp object occurrence in street/highway |

| U29y.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by sharp object occurrence at other specified place |

| U29z.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by sharp object occurrence at unspecified place |

| U2A.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by blunt object |

| U2A0.00 | [X]Intentional self -arm by blunt object occurrence at home |

| U2A1.00 | [X]Intentional self -arm by blunt object occurrence at residential institution |

| U2A3.00 | [X]Intentional self -arm by blunt object occurrence at sports/athletic area |

| U2B.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping from a high place |

| U2B0.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping from high place occurrence at home |

| U2B4.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping from high place occurring in street/highway |

| U2B6.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping from high place industrial/construction area |

| U2By.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping from high place occurrence other specified place |

| U2Bz.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping from high place occurrence unspecified place |

| U2C.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping/lying before moving object |

| U2C1.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping/lying before moving object occurrence at residential institution |

| U2C4.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping/lying before moving object occurrence in street/highway |

| U2Cy.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by jumping/lying before moving object occurrence other specified place |

| U2D.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by crashing of motor vehicle |

| U2D0.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by crashing of motor vehicle occurrence at home |

| U2D4.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by crashing of motor vehicle occurrence in street/highway |

| U2D6.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by crashing of motor vehicle occurrence industrial/construction area |

| U2E.00 | [X]Self-mutilation |

| U2y.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by other specified means |

| U2y0.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by other specified means occurrence at home |

| U2y1.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by other specified means occurrence at residential institution |

| U2yz.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by other specified means occurrence at unspecified place |

| U2z.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by unspecified means |

| U2z0.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by unspecified means occurrence at home |

| U2z2.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by unspecified means occurrence school/institution/public administrative area |

| U2zy.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by unspecified means occurrence other specified place |

| U2zz.00 | [X]Intentional self-harm by unspecified means occurrence at unspecified place |

| U30.11 | [X]Deliberate drug poisoning |

| U41.00 | [X]Hanging strangulation + suffocation undetermined intent |

| U44.00 | [X]Rifle shotgun + larger firearm discharge undetermined intent |

| U45.00 | [X]Other + unspecified firearm discharge undetermined intent |

| U4B.00 | [X]Falling jumping/pushed from high place undetermined intent |

| U4Bz.00 | [X]Fall jump/push from high place undetermined intent occurring at unspecified place |

| U72.00 | [X]Sequelae of intentional self-harm assault + event of undetermined intent |

| U720.00 | [X]Sequelae of intentional self-harm |

| ZRLfC12 | Health of the Nation Outcome Scales item 2—non-accidental self-injury |

| ZX..00 | Self-harm |

| ZX..11 | Self-damage |

| ZX1.00 | Self-injurious behavior |

| ZX1.12 | SIB—self-injurious behavior |

| ZX1.13 | Deliberate self-harm |

| ZX11.00 | Biting self |

| ZX11.11 | Bites self |

| ZX12.00 | Burning self |

| ZX13.00 | Cutting self |

| ZX13.11 | Cuts self |

| ZX15.00 | Drowning self |

| ZX18.00 | Hanging self |

| ZX19.00 | Hitting self |

| ZX19100 | Punching self |

| ZX19200 | Slapping self |

| ZX1B.00 | Jumping from height |

| ZX1B100 | Jumping from building |

| ZX1B200 | Jumping from bridge |

| ZX1B300 | Jumping from cliff |

| ZX1C.00 | Nipping self |

| ZX1E.00 | Pinching self |

| ZX1G.00 | Scratches self |

| ZX1H.00 | Self-asphyxiation |

| ZX1H100 | Self-strangulation |

| ZX1H200 | Self-suffocation |

| ZX1I.00 | Self-scalding |

| ZX1J.00 | Self-electrocution |

| ZX1K.00 | Self-incineration |

| ZX1K.11 | Setting fire to self |

| ZX1K.12 | Setting self alight |

| ZX1L.00 | Self-mutilation |

| ZX1L100 | Self-mutilation of hands |

| ZX1L200 | Self-mutilation of genitalia |

| ZX1L300 | Self-mutilation of penis |

| ZX1L600 | Self-mutilation of ears |

| ZX1LD00 | [X]Self-mutilation |

| ZX1M.00 | Shooting self |

| ZX1N.00 | Stabbing self |

| ZX1Q.00 | Throwing self in front of train |

| ZX1Q.11 | Jumping under train |

| ZX1R.00 | Throwing self in front of vehicle |

| ZX1S.00 | Throwing self onto floor |

REFERENCES

- Abdullah T. & Brown T. L. (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 934–948. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell T., Watson M., Sharp D., Lyons I. & Lewis G. (2005). Factors associated with being a false positive on the General Health Questionnaire. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40, 402–407. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0881-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjärehed J., Pettersson K., Wångby-Lundh M. & Lundh L.-G. (2013). Examining the acceptability, attractiveness, and effects of a school-based validating interview for adolescents who self-injure. The Journal of School Nursing, 29, 225–234. doi: 10.1177/1059840512458527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A., Golding J., Macleod J., Lawlor D. A., Fraser A., Henderson J., … Smith G. D. (2013). Cohort profile: The ‘Children of the 90s'—The index offspring of the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42, 111–127. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christl B., Wittchen H.-U., Pfister H., Lieb R. & Bronisch T. (2006). The accuracy of prevalence estimations for suicide attempts. How reliably do adolescents and young adults report their suicide attempts? Archives of Suicide Research, 10, 253–263. doi: 10.1080/13811110600582539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikelenboom M., Smit J. H., Beekman A. T. F., Kerkhof A. J. F. M. & Penninx B. W. J. H. (2014). Reporting suicide attempts: Consistency and its determinants in a large mental health study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23, 257–266. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E., Hawton K., Rodham K., Psychol C. & Deeks J. (2005). The prevalence of suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35, 239–250. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko S., Brohan E., Mojtabai R. & Thornicroft G. (2012). Association between public views of mental illness and self-stigma among individuals with mental illness in 14 European countries. Psychological Medicine, 42, 1741–1752. doi: 10.1017/s0033291711002558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldney R. D., Winefield A. H., Winefield H. R. & Saebel J. (2009). The benefit of forgetting suicidal ideation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39, 33–37. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes D. A. & Schulz K. F. (2002). Bias and causal associations in observational research. The Lancet, 359, 248–252. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07451-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart S. R., Musci R. J., Ialongo N., Ballard E. D. & Wilcox H. C. (2013). Demographic and clinical characteristics of consistent and inconsistent longitudinal reporters of lifetime suicide attempts in adolescence through young adulthood. Depression and Anxiety, 30, 997–1004. doi: 10.1002/da.22135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K., Rodham K., Evans E. & Weatherall R. (2002). Deliberate self harm in adolescents: Self report survey in schools in England. British Medical Journal, 325, 1207–1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidger J., Heron J., Lewis G., Evans J. & Gunnell D. (2012). Adolescent self-harm and suicidal thoughts in the ALSPAC cohort: A self-report survey in England. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 69. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-12-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B., Safer M. A., Ronsaville D., Tinsley R. & Harris S. J. (2007). The value of forgetting suicidal thoughts and behavior. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 431–438. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.4.431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G. (1994). Assessing psychiatric disorder with a human interviewer or a computer. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 48, 207–210. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.2.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G., Pelosi A. J., Araya R. & Dunn G. (1992). Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: A standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychological Medicine, 22, 465–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. M., Comtois K. A., Brown M. Z., Heard H. L. & Wagner A. (2006). Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII): development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychological Assessment, 18(3):303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madge N., Hewitt A., Hawton K., de Wilde E. J., Corcoran P., Fekete S. & Ystgaard M. (2008). Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: Comparative findings from the Child & Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 667–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars B., Heron J., Crane C., Hawton K., Kidger J., Lewis G. & Gunnell D. (2014). Differences in risk factors for self-harm with and without suicidal intent: Findings from the ALSPAC cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 168, 407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp J. J. & Gutierrez P. M. (2004). An investigation of differences between self-injurious behavior and suicide attempts in a sample of adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34, 12–23. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.12.27769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morthorst B., Krogh J., Erlangsen A., Alberdi F. & Nordentoft M. (2011). Effect of assertive outreach after suicide attempt in the AID (assertive intervention for deliberate self harm) trial: randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;345:e4972-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock M. K. & Kessler R. C. (2006). Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts versus suicide gestures: analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(3):616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan M. & Fitzgerald M. (1998). Suicidal ideation and acts of self-harm among Dublin school children. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 427–433. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ougrin D. & Boege I. (2013). Brief report: The self harm questionnaire: A new tool designed to improve identification of self harm in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton G. C., Coffey C., Posterino M., Carlin J. B., Wolfe R. & Bowes G. (1999). A computerised screening instrument for adolescent depression: Population-based validation and application to a two-phase case-control study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34, 166–172. doi: 10.1007/s001270050129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton G. C., Olsson C., Bond L., Toumbourou J. W., Carlin J. B., Hemphill S. A. & Catalano R. F. (2008). Predicting female depression across puberty: A two-nation longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 1424–1432. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3181886ebe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percy A., McAlister S., Higgins K., McCrystal P. & Thornton M. (2005). Response consistency in young adolescents’ drug use self-reports: A recanting rate analysis. Addiction, 100, 189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plöderl M., Kralovec K., Yazdi K. & Fartacek R. A. (2011). Closer Look at Self-Reported Suicide Attempts: False Positives and False Negatives. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynders A., Kerkhof A. J. F. M., Molenberghs G. & Van Audenhove C. (2014). Attitudes and stigma in relation to help-seeking intentions for psychological problems in low and high suicide rate regions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 231–239. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0745-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S. & Heath N. (2002). A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Safer D. J. (1997). Self-reported suicide attempts by adolescents. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 9, 263–269. doi: 10.3109/10401239709147808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K. H., Davies N., Metcalfe C., Windmeijer F., Martin R. M. & Gunnell D. (2013). Validation of suicide and self-harm records in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 76, 145–157. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velting D. M., Rathus J. H. & Asnis G. M. (1998). Asking adolescents to explain discrepancies in self-reported suicidality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 28, 187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (1991). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (3rd ed.). London, UK: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D., Waylen A., Samara M., Steer C., Goodman R., Ford T. & Lamberts K. (2009). Selective drop-out in longitudinal studies and non-biased prediction of behaviour disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195, 249–256. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ystgaard M., Arensman E., Hawton K., Madge N., van Heeringen K., Hewitt A. & Fekete S. (2009). Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: Comparison between those who receive help following self-harm and those who do not. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 875–891. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]