Abstract

Background/Aims

Tempol is a protective antioxidant against ischemic injury in many animal models. The molecular mechanisms are not well understood. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) is a master transcription factor during oxidative stress, which is enhanced by activation of protein kinase C (PKC) pathway. Another factor, tubular epithelial apoptosis, is mediated by activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (PKB, Akt) signaling pathway during renal ischemic injury. We tested the hypothesis that tempol activates PKC or PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathways to transcribe many genes that coordinate endogenous antioxidant defense.

Methods

The right renal pedicle was clamped for 45 minutes and the left kidney was removed to study renal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in C57BL/6 mice. The response was assessed from serum parameters, renal morphology and renal expression of PKC, phosphorylated-PKC (p-PKC), Nrf2, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), Akt, phosphorylated-Akt (p-Akt), pro-caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 in groups of sham and I/R mice given vehicle, or tempol (50 or 100 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection).

Results

The serum malondialdehyde (MDA, marker of reactive oxygen species) doubled and the BUN and creatinine increased 5- to 10-fold after I/R injury. Tempol (50 or 100 mg/kg) prevented the increases in MDA but only tempol (50 mg/kg) lessened the increases in BUN and creatinine and moderated the acute tubular necrosis. I/R did not change expression of PKC or p-PKC but reduced renal expression of Nrf2, p-Akt, HO-1 and pro-caspase-3 and increased cleaved caspase-3. Tempol (50 mg/kg) prevented these changes produced by I/R whereas tempol (100 mg/kg) had lesser or inconsistent effects.

Conclusion

Tempol (50 mg/kg) prevents lipid peroxidation and attenuates renal damage after I/R injury. The beneficial pathway apparently is not dependent on upregulation or phosphorylation of PKC, at lower tempol doses, does implicate upregulation of Akt with expression of Nrf2 that could account for the increase in the antioxidant gene HO-1 and a reduction in the cleavage of the cellular damage marker pro-caspase-3.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Ischemia reperfusion, Tempol, Nrf2

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common and catastrophic complication in hospitalized patients [1, 2]. Although AKI has been studied extensively, the intracellular signaling pathways that are involved in AKI remain unclear [3].

Renal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury is a common cause of AKI. It initiates a complex and interrelated sequence of events within the kidney that culminate in renal injury and death of renal cells [4]. Endothelial dysfunction and tubular cell injury through ATP depletion, accumulation of intracellular Ca2+, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proinflammatory cytokines, and apoptotic pathway have all been implicated [5, 6]. Of these, the excessive generation of ROS causes damage and death of renal tubular epithelial cells [7]. The role of ROS in the pathophysiology of I/R injury is supported by increased formation of lipid peroxidation and other toxic products following renal injury [8, 9].

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) is a master regulator of antioxidant defense gene [10] and a master transcription factor released during oxidative stress [11]. The accumulated Nrf2 in the nucleus binds to antioxidant response elements (ARE) on the genes for phase 2 enzyme that upregulate many proteins involved in the metabolism of ROS during I/R injury [12-14]. Therefore, we hypothesize that upregulation of Nrf2 signaling may reduce renal damage and enhance repair after I/R injury.

Activation of the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway enhances Nrf2 expression and can protect kidney against I/R damage [15, 16]. However, tubular epithelial apoptosis is another factor that is induced by renal I/R injury and could account for acute tubular necrosis. Indeed, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt (PI3K/Akt) pathway can mediate cell survival in many cell types [17], including renal cells [18]. This pathway was originally recognized to play a critical role in regulating cell growth and survival [19] and more recently has been implicated in the protection of liver and kidney against I/R injury by moderating the inflammatory response [20, 21]. This may involve in activation of Nrf-2 but its specific role is not established. Renal cell injury culminates in regeneration and repair, or in renal cell apoptosis.

The redox-cycling antioxidant tempol has been much studied. It can act both as a superoxide dismutase (SOD) and as a catalase member[22], thereby reducing tissue levels of both superoxide (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Indeed, a mouse model of chronic kidney disease (reduced renal mass/high salt diet) excreted > 6-fold more 8-isoprostane F2α (generated by interaction of O2•− and arachidonate) and 2-fold more H2O2 [23]. All of these were almost restored to levels of sham operated mice by tempol administration. Tempol can protect the kidneys against acute inflammation by restoring hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1a) expression, increasing renal parenchymal PO2 and down-regulating transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) expression [24]. Unbalance among oxygen, NO, and ROS is an important component of the pathogenesis of I/R-induced AKI. Indeed, tempol can improve tissue NO and PO2, reduce TGFβ and the associated inflammation and protect the kidney from I/R-induced injury [25-28]. However, the mechanism has not been well elucidated. Thus, the aim of the present investigation is to investigate the protective role of tempol in renal I/R injury and its interaction with the PKC and/or PI3K/Akt pathways.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Experimental Animals and Protocols

Male C57BL/6 mice weighing 24-28 g (12 weeks old) were obtained from Zhejiang Medical Animal Centre (Hangzhou, China). Mice were housed under climate-controlled conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle and provided with standard food and water. All experimental protocols and animal handling procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH, USA) guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Committees for Animal Experiments at Zhejiang University in China. Tempol (50 or 100 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) was administered at 60 minutes prior to the renal I/R injury [29, 30].

Kidney ischemia/reperfusion model

Mice were randomly divided into four groups: (1) sham; (2) I/R group (vehicle group); (3) I/R + tempol (50 mg/kg) group; and (4) I/R + tempol (100 mg/kg) group. To induce I/R model, mice were anesthetized with 3% chloral hydrate. The right renal pedicle clamped for 45 minutes and left nephrectomy performed to produce severe renal injury. Thereafter, the clamp was released to allow reperfusion. Sham-operated mice were dissected as above, but with no occlusion of the renal pedicle. The rectal temperature was monitored throughout and maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C with a heating blanket. All mice were sacrificed by decapitation at 24 h after reperfusion, and the kidneys were dissected and collected for further analysis.

Determination of serum creatinine, BUN and MDA

Before euthanatized, blood was sampled from the inferior vena cava and centrifuged at 3000 rpm, 4°C for 15 min. Serum creatinine and BUN were measured by an automatic biochemical analyzer. Serum Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration was measured by a Kit (Lipid Peroxidation MDA Assay Kit, Beyotime Biotechnology, China).

Morphology

Renal tissue fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde was processed by dehydration and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 4 μm intervals and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) for histological assessment by a designated pathologist blinded to the experimental groups.

Immunoblotting analysis

After euthanatized, the kidneys were dissected and stored at −80°C. Frozen kidney tissue samples were homogenized in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.5% Triton X-100, 4 mM EGTA, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 50 μg/mL leupeptin, 30 μg/mL aprotinin and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The homogenate was centrifuged 5 min at 10,000 g at 4°C. The insoluble pelleted nuclei were resuspended in ice-cold buffer; and nuclear protein fractions were prepared as described previously [31].

Cell lysates or nuclear extracts from kidney tissue containing equivalent amounts of protein were analyzed by 10-13.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDSPAGE) as described previously [32-34]. Proteins were transferred to an immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for 1h at 50 V. Membranes were blocked in 20 mM Tris-HCl (PH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 5% fat-free milk powder for 1 h and immunodetected with antibodies to Nrf2 (polyclonal antibody; 1:2000), Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (monoclonal antibody; 1:2000), PKC (polyclonal antibody; 1:2000), p-PKC (monoclonal antibody; 1:2000), β-actin (monoclonal antibody; 1:5000) (Abcam Cambridge, UK), Akt (polyclonal antibody; 1:2000), p-Akt (ser473 monoclonal antibody; 1:2000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) and lamin B1 (monoclonal antibody; 1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). After incubation, membranes were incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000). Immunoreactivity was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, UK) in an automated imaging analysis system (Tanon 5200 Multi, Tanon Science & Technology Inc, Shanghai, China).

Statistical analysis

The significance of the differences between the different groups was determined using a one-way ANOVA and considered to be significant at P < 0.05. All data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Results

Effects of tempol on renal function after I/R injury

The serum BUN and creatinine increased 5- to 10-folds in mice after renal I/R injury (vehicle group) and were significantly, but modestly, reduced by tempol (50 mg/kg), but not by tempol (100 mg/kg) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of tempol on renal functional parameters at 24 h reperfusion after transient renal ischemia

| Experimental group | Serum BUN (mmol/L) |

Serum creatinine (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Sham | 12.8 ± 0.7 | 20.9 ± 3.8 |

| Vehicle | 67.3 ± 3.9 ** | 211.3 ± 17.5 ** |

| Vehicle+Tempol, 50mg/kg | 59.9 ± 4.6 **# | 172.4 ± 29.1 **# |

| Vehicle+Tempol, 100mg/kg | 63.8 ±6.3** | 224.7 ± 14.8 ** |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD from seven independent animals ( n=7).

p < 0.01 vs sham group;

p < 0.05 vs vehicle group

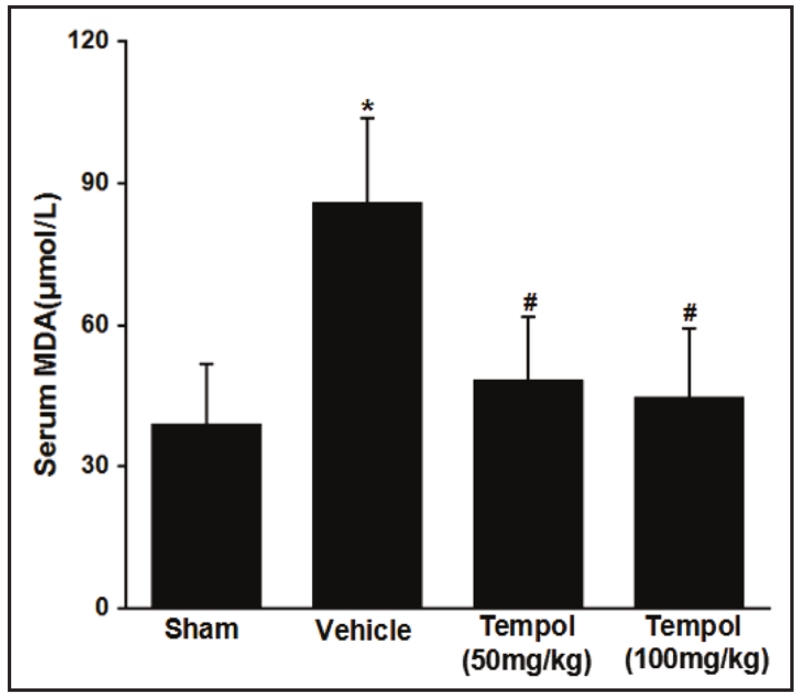

Effect of tempol on lipid peroxidation after I/R injury

MDA is a convenient and stable marker of lipid peroxidation [35, 36]. Serum MDA doubled in mice after I/R injury but this was prevented by tempol (50 or 100 mg/kg) (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of renal I/R injury and tempol on serum MDA. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from 7 independent animals (n=7). * p <0.05 vs sham group; # p <0.05 vs vehicle group.

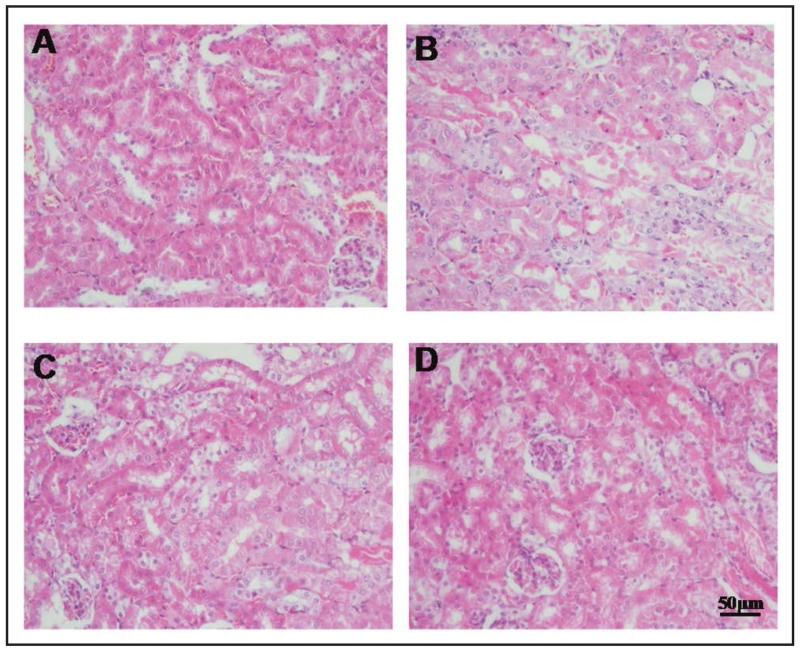

Effects of tempol on renal morphology after I/R injury

Renal I/R led to widespread disruption of the tubular architecture, tubule dilation, swelling and necrosis, and luminal congestion with loss of brush border [37] (Figure 2 A and B). These changes were markedly reduced in mice pretreated with tempol (50 and 100 mg/kg) (Figure 2 C and D).

Fig. 2.

Tempol attenuates the morphologic changes of I/R injury. Representative H&E staining kidney sections taken from sham-operated group (A), I/R group (vehicle group) (B) and I/R pretreated with tempol (50 and 100 mg/kg) (C and D). Figures are representative of at least three experiments performed on different groups (n=3).

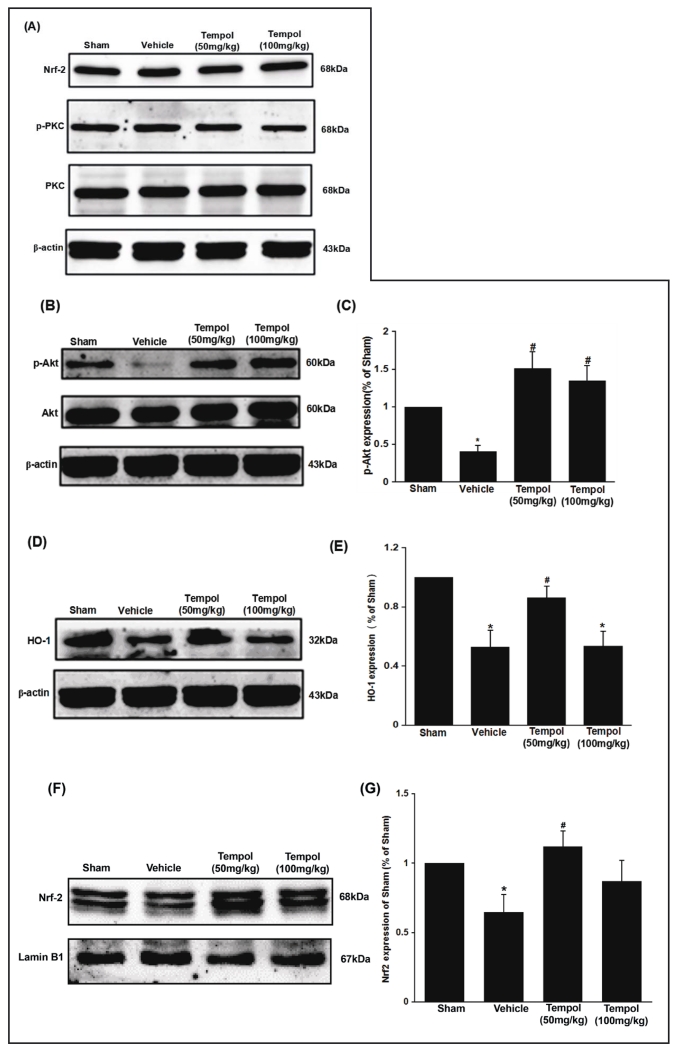

Effect of tempol on the expression of PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 and PKC/Nrf2 pathway proteins after renal I/R injury

Renal I/R injury did not change the cytoplasmic expression of Nrf-2, PKC or p-PKC (Figure 3A) but reduced p-Akt (Figure 3 B and C) and HO-1 (Figure 3 D and E) and nuclear expression of Nrf-2 (Figure 3 F and G). Pretreatment with the lower dose of tempol (50 mg/kg) did not change the expression of cytoplasmic Nrf-2, PKC or p-PKC but restored the reduced p-Akt, HO-1 and the nuclear Nrf2 expression in I/R mouse kidneys. The high dose of tempol (100 mg/kg) failed to restore HO-1 or nuclear Nrf-2 expression.

Fig. 3.

Effect of tempol on the expression of PKC/Nrf2 and PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathways induced by ischemia/reperfusion. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from 5 independent animals (n=5). * p <0.05 vs sham group; # p <0.05 vs vehicle group.

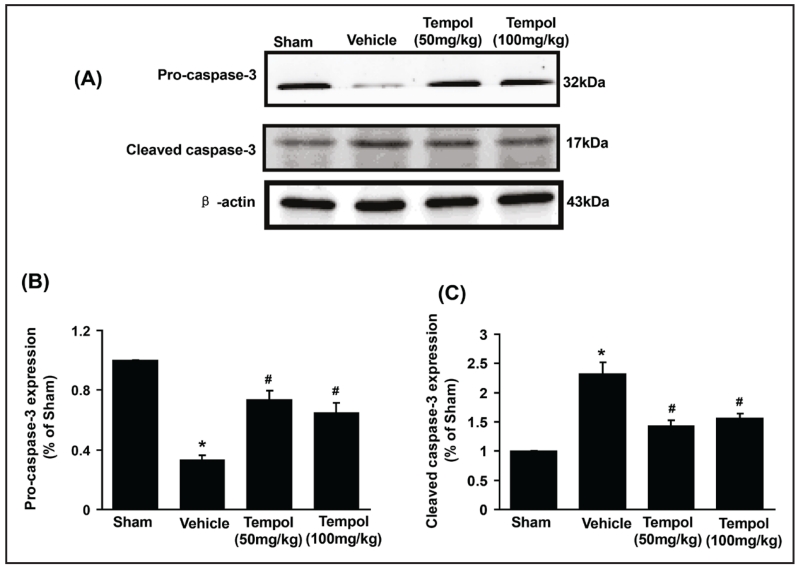

Effect of tempol on expression of apoptotic signaling pathway proteins after renal I/R injury

Caspase-3 is an important marker of cell and tissue apoptosis. The expression of pro-caspase was reduced, and cleaved caspase-3 increased after I/R injury (Figure 4A, B and C). Both doses of tempol moderated these markers of renal cell apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

Effect of tempol on the expression of caspase-3 pathway in renal I/R injury. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from 5 independent animals (n=5). * p <0.05 vs sham group; # p <0.05 vs vehicle group.

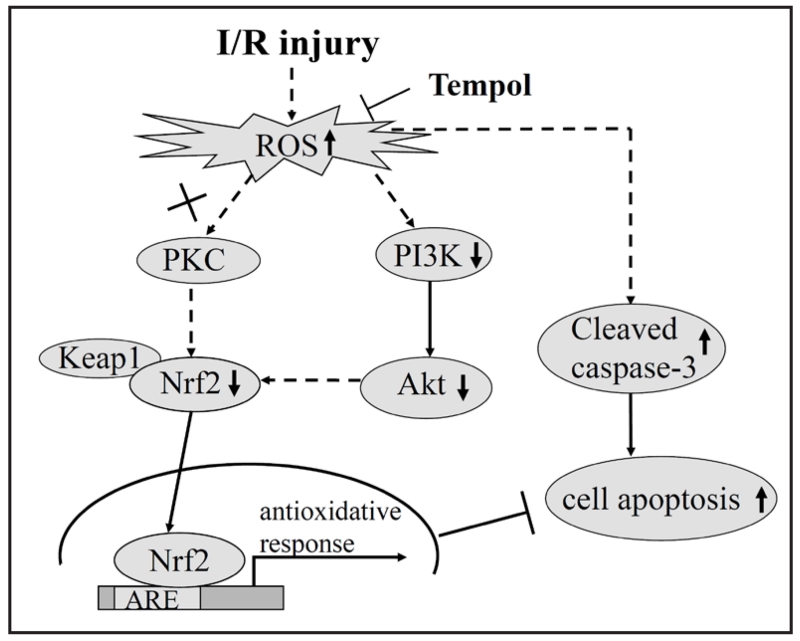

Schematic illustration of the potential mechanisms of tempol on I/R injury induced oxidative stress and apoptotic signaling

These data suggest that I/R injury increases ROS that down-regulate the expression of Akt and Nrf2, thereby reducing its antioxidant responses, promoting activation of caspase-3 and culminating in renal cell death and dysfunction. Pharmacological inhibition of ROS formation by tempol, especially at the lower dose, reduced or prevented these effects.

Discussion

AKI causes a high mortality [38]. Its primary causes are renal ischemia, hypoxia or nephrotoxicity [39, 40]. I/R injury increases renal ROS and decreases endogenous antioxidants [41]. I/R injury occurs in many clinical circumstances in which kidney damage can be some causes of renal transplantation, shock, and vascular surgery and administration of radiology contrast agents. However, therapeutic modalities that prevent acute kidney injury are still extremely limited. The pathophysiological mechanism of I/R injury includes endothelial dysfunction, generation of ROS and pro-inflammatory cytokines and activation of apoptotic pathways [42]. Signal pathways activated by I/R injury include PKC, Nrf2, PI3K/Akt, inflammation and apoptosis [43-46].

Our results confirm reports that tempol protects the kidney from ischemic damage [25-28], but shows a complex and dose-dependent mechanism. Although there were some inconsistent results between the doses of tempol used, the current study demonstrated the following findings: (1) I/R renal injury increases lipid peroxidation (a marker of ROS). (2) Both doses of tempol reduced the morphologic renal damage and corrected the activation of the apoptotic pathway (from the expression of caspase and pro-caspase). (3) The lower dose of tempol restored Nrf2 activation (from nuclear expression), downstream signaling (from HO-1 expression) and upstream activation (from p-Akt expression), but paradoxically the high dose of tempol was not effective. The PKC, p-PKC was not activated by I/R injury, nor was the cytoplasmic Nrf2 expression altered.

Oxidative stress is involved in acute kidney injury due to ischemia-reperfusion and chemotherapy-induced nephrotoxicity. Tempol can directly metabolize ROS, including both superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. However, tempol has also been shown to reset the endogenous anti-oxidant defense system so as to provide additional, and more prolonged, anti-oxidant effect [22, 28]. This study demonstrates that one important mechanism of cellular defense after tempol involves upregulation of Nrf2 and its downstream genes, including HO-1. However, this pathway was only activated after lower dose of tempol. On the other hand, low and high doses of tempol prevented lipid peroxidation, activated Akt, and prevented cellular apoptosis and renal damage. This suggests that there may be multiple, dose-dependent effects of tempol to alleviate oxidative stress and its consequences in the kidney that may underline some previous inconsistent reports in the literatures [25]. The data suggested that the renal injury induced by ischemia/reperfusion was related to oxidative stress and that tempol restored the expression of Nrf2-dependent cytoprotective pathways and that blocked ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis.

Conclusion

Our findings using the ischemia model demonstrated that tempol effectively prevented against I/R-induced renal injury through PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 and caspase-3, not PKC/Nrf2 signaling pathway.

Fig. 5.

Diagrammatic representation of the effect of tempol on the oxidative stress-mediated the changes of PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 and apoptotic signaling in renal I/R injury.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants to En Yin Lai and Huiping Wang from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31471100) and Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. LY13H070002); to Renjun Wang from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81202527); to Christopher S. Wilcox from The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK-49870 and DK-36079) and The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-68686), and to Ruisheng Liu from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK098582 and DK099276).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors of this manuscript state that they do not have any conflict of interests and nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Edelstein CL, Ling H, Wangsiripaisan A, Schrier RW. Emerging therapies for acute renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:S89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly KJ, Molitoris BA. Acute renal failure in the new millennium: Time to consider combination therapy. Semin Nephrol. 2000;20:4–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreucci M, Michael A, Kramers C, Park KM, Chen A, Matthaeus T, Alessandrini A, Haq S, Force T, Bonventre JV. Renal ischemia/reperfusion and atp depletion/repletion in llc-pk(1) cells result in phosphorylation of fkhr and fkhrl1. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1189–1198. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosieradzki M, Rowinski W. Ischemia/reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: Mechanisms and prevention. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:3279–3288. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonventre JV, Zuk A. Ischemic acute renal failure: An inflammatory disease? Kidney Int. 2004;66:480–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu D, Chen X, Ding R, Qiao X, Shi S, Xie Y, Hong Q, Feng Z. Ischemia/reperfusion induce renal tubule apoptosis by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and l-type ca2+ channel opening. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:487–499. doi: 10.1159/000113107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patschan D, Patschan S, Muller GA. Inflammation and microvasculopathy in renal ischemia reperfusion injury. J Transplant. 2012;2012:764154. doi: 10.1155/2012/764154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCord JM. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan Q, Hong S, Han S, Zeng L, Liu F, Ding G, Kang Y, Mao J, Cai M, Zhu Y, Wang QX. Preconditioning with physiological levels of ethanol protect kidney against ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F, Pu C, Zhou P, Wang P, Liang D, Wang Q, Hu Y, Li B, Hao X. Cinnamaldehyde prevents endothelial dysfunction induced by high glucose by activating nrf2. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:315–324. doi: 10.1159/000374074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li G, Li CX, Xia M, Ritter JK, Gehr TW, Boini K, Li PL. Enhanced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition associated with lysosome dysfunction in podocytes: Role of p62/sequestosome 1 as a signaling hub. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:1773–1786. doi: 10.1159/000373989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonard MO, Kieran NE, Howell K, Burne MJ, Varadarajan R, Dhakshinamoorthy S, Porter AG, O’Farrelly C, Rabb H, Taylor CT. Reoxygenation-specific activation of the antioxidant transcription factor nrf2 mediates cytoprotective gene expression in ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 2006;20:2624–2626. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5097fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah ZA, Li RC, Thimmulappa RK, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Biswal S, Dore S. Role of reactive oxygen species in modulation of nrf2 following ischemic reperfusion injury. Neuroscience. 2007;147:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Hu X, Xie J, Xu W, Jiang H. Beta-1-adrenergic receptors mediate nrf2-ho-1-hmgb1 axis regulation to attenuate hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocytes injury in vitro. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:767–777. doi: 10.1159/000369736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H, Park YH, Jeon YT, Hwang JW, Lim YJ, Kim E, Park SY, Park HP. Sevoflurane post-conditioning increases nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor and haemoxygenase-1 expression via protein kinase c pathway in a rat model of transient global cerebral ischaemia. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114:307–318. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buelna-Chontal M, Guevara-Chavez JG, Silva-Palacios A, Medina-Campos ON, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Zazueta C. Nrf2-regulated antioxidant response is activated by protein kinase c in postconditioned rat hearts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;74:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hausenloy DJ, Tsang A, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. Ischemic preconditioning protects by activating prosurvival kinases at reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H971–976. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00374.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joo JD, Kim M, D’Agati VD, Lee HT. Ischemic preconditioning provides both acute and delayed protection against renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3115–3123. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fry MJ. Structure, regulation and function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1226:237–268. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravingerova T, Carnicka S, Nemcekova M, Ledvenyiova V, Adameova A, Kelly T, Barlaka E, Galatou E, Khandelwal VK, Lazou A. Ppar-alpha activation as a preconditioning-like intervention in rats in vivo confers myocardial protection against acute ischaemia-reperfusion injury: Involvement of pi3k-akt. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;90:1135–1144. doi: 10.1139/y2012-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sano T, Izuishi K, Hossain MA, Kakinoki K, Okano K, Masaki T, Suzuki Y. Protective effect of lipopolysaccharide preconditioning in hepatic ischaemia reperfusion injury. HPB (Oxford) 2010;12:538–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilcox CS, Pearlman A. Chemistry and antihypertensive effects of tempol and other nitroxides. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:418–469. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai EY, Luo Z, Onozato ML, Rudolph EH, Solis G, Jose PA, Wellstein A, Aslam S, Quinn MT, Griendling K, Le T, Li P, Palm F, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Effects of the antioxidant drug tempol on renal oxygenation in mice with reduced renal mass. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F64–74. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00005.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roson MI, Della Penna SL, Cao G, Gorzalczany S, Pandolfo M, Toblli JE, Fernandez BE. Different protective actions of losartan and tempol on the renal inflammatory response to acute sodium overload. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224:41–48. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilcox CS. Effects of tempol and redox-cycling nitroxides in models of oxidative stress. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126:119–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujii T, Takaoka M, Ohkita M, Matsumura Y. Tempol protects against ischemic acute renal failure by inhibiting renal noradrenaline overflow and endothelin-1 overproduction. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:641–645. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chatterjee PK, Cuzzocrea S, Brown PA, Zacharowski K, Stewart KN, Mota-Filipe H, Thiemermann C. Tempol, a membrane-permeable radical scavenger, reduces oxidant stress-mediated renal dysfunction and injury in the rat. Kidney Int. 2000;58:658–673. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aksu U, Ergin B, Bezemer R, Kandil A, Milstein DM, Demirci-Tansel C, Ince C. Scavenging reactive oxygen species using tempol in the acute phase of renal ischemia/reperfusion and its effects on kidney oxygenation and nitric oxide levels. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2015;3:57. doi: 10.1186/s40635-015-0057-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuzzocrea S, McDonald MC, Mazzon E, Filipe HM, Centorrino T, Lepore V, Terranova ML, Ciccolo A, Caputi AP, Thiemermann C. Beneficial effects of tempol, a membrane-permeable radical scavenger, on the multiple organ failure induced by zymosan in the rat. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:102–111. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200101000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuzzocrea S, McDonald MC, Mazzon E, Siriwardena D, Costantino G, Fulia F, Cucinotta G, Gitto E, Cordaro S, Barberi I, De Sarro A, Caputi AP, Thiemermann C. Effects of tempol, a membrane-permeable radical scavenger, in a gerbil model of brain injury. Brain Res. 2000;875:96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shioda N, Han F, Moriguchi S, Fukunaga K. Constitutively active calcineurin mediates delayed neuronal death through fas-ligand expression via activation of nfat and fkhr transcriptional activities in mouse brain ischemia. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1506–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han F, Shirasaki Y, Fukunaga K. Microsphere embolism-induced endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression mediates disruption of the blood-brain barrier in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2006;99:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang GS, Tian Y, Huang JY, Tao RR, Liao MH, Lu YM, Ye WF, Wang R, Fukunaga K, Lou YJ, Han F. The gamma-secretase blocker dapt reduces the permeability of the blood-brain barrier by decreasing the ubiquitination and degradation of occludin during permanent brain ischemia. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2013;19:53–60. doi: 10.1111/cns.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang GS, Ye WF, Tao RR, Lu YM, Shen GF, Fukunaga K, Huang JY, Ji YL, Han F. Expression profiling of ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent signaling molecules in the rat dorsal and ventral hippocampus after acute lead exposure. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2012;64:619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rybak LP, Husain K, Whitworth C, Somani SM. Dose dependent protection by lipoic acid against cisplatininduced ototoxicity in rats: Antioxidant defense system. Toxicol Sci. 1999;47:195–202. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/47.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Del Rio D, Stewart AJ, Pellegrini N. A review of recent studies on malondialdehyde as toxic molecule and biological marker of oxidative stress. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;15:316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharples EJ, Patel N, Brown P, Stewart K, Mota-Philipe H, Sheaff M, Kieswich J, Allen D, Harwood S, Raftery M, Thiemermann C, Yaqoob MM. Erythropoietin protects the kidney against the injury and dysfunction caused by ischemia-reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2115–2124. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000135059.67385.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rewa O, Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury-epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:193–207. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basile DP, Anderson MD, Sutton TA. Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:1303–1353. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arakelyan K, Cantow K, Hentschel J, Flemming B, Pohlmann A, Ladwig M, Niendorf T, Seeliger E. Early effects of an x-ray contrast medium on renal t(2) */t(2) mri as compared to short-term hyperoxia, hypoxia and aortic occlusion in rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2013;208:202–213. doi: 10.1111/apha.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palipoch S. A review of oxidative stress in acute kidney injury: Protective role of medicinal plants-derived antioxidants. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2013;10:88–93. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i4.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munshi R, Hsu C, Himmelfarb J. Advances in understanding ischemic acute kidney injury. BMC Med. 2011;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rong S, Hueper K, Kirsch T, Greite R, Klemann C, Mengel M, Meier M, Menne J, Leitges M, Susnik N, Haller H, Shushakova N, Gueler F. Renal pkc-epsilon deficiency attenuates acute kidney injury and ischemic allograft injury via tnf-alpha-dependent inhibition of apoptosis and inflammation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;307:F718–726. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00372.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu QQ, Wang Y, Senitko M, Meyer C, Wigley WC, Ferguson DA, Grossman E, Chen J, Zhou XJ, Hartono J, Winterberg P, Chen B, Agarwal A, Lu CY. Bardoxolone methyl (bard) ameliorates ischemic aki and increases expression of protective genes nrf2, ppargamma, and ho-1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F1180–1192. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00353.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang L, Zhu Z, Liu J, Hu Z. Protective effect of n-acetylcysteine (nac) on renal ischemia/reperfusion injury through nrf2 signaling pathway. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2014;34:396–400. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2014.908916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El Eter EA, Aldrees A. Inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines by sch79797, a selective protease-activated receptor 1 antagonist, protects rat kidney against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shock. 2012;37:639–644. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182507774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]