Abstract

BACKGROUND

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of visual loss among the elderly. A key cell type involved in AMD, the retinal pigment epithelium, expresses a G protein–coupled receptor that, in response to its ligand, L-DOPA, up-regulates pigment epithelia–derived factor, while down-regulating vascular endothelial growth factor. In this study we investigated the potential relationship between L-DOPA and AMD.

METHODS

We used retrospective analysis to compare the incidence of AMD between patients taking vs not taking L-DOPA. We analyzed 2 separate cohorts of patients with extensive medical records from the Marshfield Clinic (approximately 17,000 and approximately 20,000) and the Truven MarketScan outpatient and databases (approximately 87 million) patients. We used International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes to identify AMD diagnoses and L-DOPA prescriptions to determine the relative risk of developing AMD and age of onset with or without an L-DOPA prescription.

RESULTS

In the retrospective analysis of patients without an L-DOPA prescription, AMD age of onset was 71.2, 71.3, and 71.3 in 3 independent retrospective cohorts. Age-related macular degeneration occurred significantly later in patients with an L-DOPA prescription, 79.4 in all cohorts. The odds ratio of developing AMD was also significantly negatively correlated by L-DOPA (odds ratio 0.78; confidence interval, 0.76–0.80; P <.001). Similar results were observed for neovascular AMD (P <.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Exogenous L-DOPA was protective against AMD. L-DOPA is normally produced in pigmented tissues, such as the retinal pigment epithelium, as a byproduct of melanin synthesis by tyrosinase. GPR143 is the only known L-DOPA receptor; it is therefore plausible that GPR143 may be a fruitful target to combat this devastating disease.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), GPR143, L-DOPA, Movement disorder, Parkinson’s disease, Retrospective study, Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)

Developing a new drug costs more than $2 billion and takes 13.5 years from discovery to market. Drug repositioning does not require anywhere near these costs and has been successfully used for more than a dozen drugs.1 Electronic medical records (EMRs) offer a powerful tool to examine the effects of a drug on conditions for which it was not originally prescribed.2 Indeed, long-term EMRs can be mined for retrospective data to develop a “virtual prospective” drug repurposing study. Here we use EMR analysis to determine whether L-DOPA, a drug used for movement disorders, is a candidate for treatment of an unrelated disease, age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness in developed nations,3–6 even accounting for 10% of blindness in Sudan.7 Despite years of intensive research efforts, we do not know the cause of AMD. Patients with AMD typically experience a gradual loss of central vision over years. Most patients develop geographic atrophy, a progressive loss of the region of highest visual acuity, the macula. When this atrophy involves the center of the macula, visual acuity drops precipitously. The other form of AMD includes the development of abnormal blood vessels, or neovascularization, leading to “wet” or “exudative” AMD. These abnormal blood vessels, if left untreated, result in progressive leakage, bleeding, and irreversible scarring of the macula.8 Wet AMD tends to develop suddenly and progress rapidly, resulting in catastrophic vision loss.9–15 Although wet AMD only occurs in 10%–15% of AMD cases, it is responsible for most blindness due to AMD.16

The impact of AMD on Americans is staggering. Age-related macular degeneration affects patients of all ethnicities, but vision loss due to AMD is most common among Caucasians and is approximately 5-fold less common among those of African descent, with intermediate risk in Hispanic and Asian populations.4,6,17 Approximately 9 million people in the United States have moderate to severe AMD, and this is projected to increase to more than 16 million by the year 2020.12,18 Approximately 1.75 million of these people have vision loss or immediate vision-threatening disease (wet AMD or geographic atrophy).18

The cost associated with AMD will only increase as the number of people over the age of 65 years increases. For those patients with vision loss due to AMD through geographic atrophy, there is no treatment at all, only vitamin supplements that may slow vision loss.19,20 Recent progress in the use of agents that inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has significantly improved the outcomes of patients who develop wet AMD.21–24 These treatments have been successful in preserving vision, but this comes at a cost of significant discomfort, inconvenience, and expense. The most successful treatment involves repeated injections of VEGF inhibitors directly into the eye. Although successful, these drugs can be incredibly expensive.25 The cost of this treatment strategy in 2010 through Medicare Part B was just under $2 billion.26

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE.

Patients prescribed L-DOPA are less likely to develop age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

In patients taking L-DOPA who did develop AMD, the age of onset was significantly delayed.

L-DOPA may both prevent and delay AMD in aged patients.

We have previously discovered a G protein–coupled receptor that binds to and is activated by L-DOPA.27 This receptor, GPR143, is expressed in the retinal pigment epithelium, a primary support tissue for the neurosensory retina. Further, we have shown that GPR143 controls trophic factor release by the retinal pigment epithelium,27,28 such that GPR143 signaling may protect from AMD. Herein we test this novel hypothesis to investigate whether L-DOPA may be repositioned as an AMD preventative drug, using EMRs in a virtual prospective clinical trial.

METHODS

We used International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes 362.50, 362.51, 362.52, and 362.57 to capture all AMD diagnoses from each database. We used prescription history of L-DOPA, rather than Parkinson’s disease diagnosis (PD: ICD-9 332), because many with Parkinson’s disease do not take L-DOPA, and individuals without Parkinson’s disease are prescribed L-DOPA for other movement disorders. Because our real question related to L-DOPA and AMD, regardless of why they were prescribed L-DOPA, this creates an unbiased observation.

Statistical analysis included t test analysis and binomial testing for the Marshfield Clinic Cohort (equation below) to examine the population distribution. For the Truvan MarketScan Cohort we limited our analysis to those with a record of Ophthalmology, for any reason (15,215,458 individuals). This allows for selecting patients with access to ophthalmologists or other healthcare providers diagnosing ophthalmic conditions without affecting the potential relationship between L-DOPA use and AMD. The prevalence of AMD in this selected population was 4.5%, indicating that AMD was not overrepresented by including individuals who had an ophthalmology history.

For comparisons, using SPSS (version 22; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill), an independent-samples t test was used to compare the age difference between the groups, and multinomial regression analysis was used to control for potential confounding variables (age and gender) and to evaluate the association between L-DOPA use and diagnosis of AMD by calculating odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P-values.

RESULTS

Marshfield Clinic Cohorts

To determine the possible relationship between L-DOPA and AMD, we examined clinical data from the Marshfield Clinic’s Personalized Medicine Research Project (PMRP) (N = approximately 20,000),29 plus an additional non-overlapping group of approximately 17,000 patients with long-term nearly complete electronic health records in the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area.30 Institutional review board approval was obtained. In the PMRP cohort, AMD was present in 5.7% of the subjects (n = 1142), and Parkinson’s disease (ICD-9 332) was present in 0.85% of the subjects (n = 170). However, AMD and Parkinson’s disease were found together in 0.21% of the subjects (n = 43), 4 times the expected rate if they are independent variables, not unexpected because both AMD and Parkinson’s disease are disorders of aging and may even share some common etiology. However, the etiologies of the 2 diseases have not previously been shown to intersect, and they do not share any known risk factors. In fact, one of the main risk factors for AMD, smoking,31 may protect from Parkinson’s disease.32,33

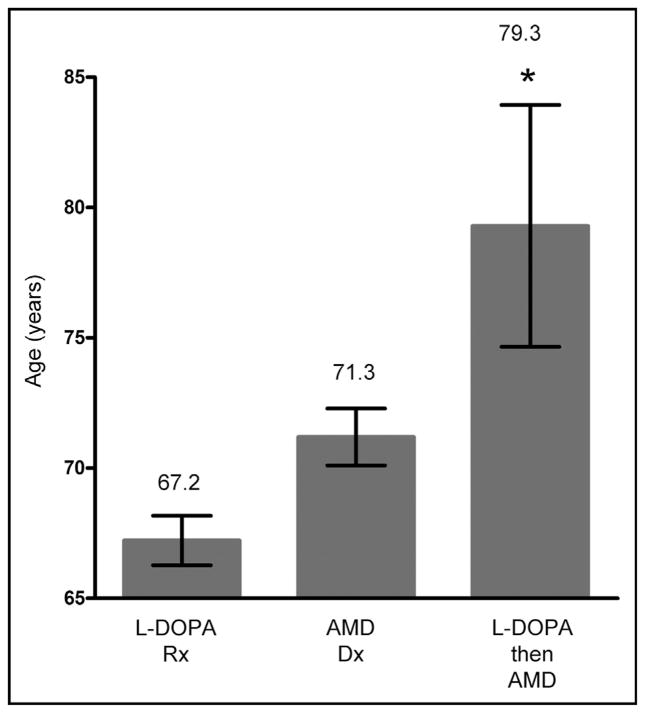

Because we are primarily interested in determining the effect of L-DOPA on AMD and because only 67% of the Parkinson’s disease patients in PMRP have been given L-DOPA (and other patients are prescribed L-DOPA), subsequent analyses included all patients taking L-DOPA (1.1% of PMRP, n = 229) with or without Parkinson’s disease. We found that an AMD diagnosis (Dx) and L-DOPA prescription (Rx) also occurred together in the EMR 3 times more frequently than expected (in 0.2% of subjects, n = 39), even after stratifying for age. To control for this, we examined the 39 patients with both an AMD Dx and L-DOPA Rx in their EMR. Because the average age of L-DOPA Rx is 67.1 years, and the average age of onset of AMD in the PMRP cohort is 71.2 years, we would expect a bias that L-DOPA Rx appears in the EMR earlier then AMD Dx in patients with both in their EMR. However, the opposite trend was found. Of the 39 patients in PMRP with both AMD and L-DOPA in their EMR, 30 received L-DOPA after the AMD diagnosis; 4 received L-DOPA in the same year; and 5 received L-DOPA before the AMD diagnosis. This same trend was noted within the major age brackets: ages 65–70 years: 9 LDOPA after AMD, 1 L-DOPA before AMD; ages 70–75 years: 10 L-DOPA after AMD, 1 same year; ages 75–80 years: 4 L-DOPA after AMD, 2 L-DOPA before AMD, 2 same year; ages 80–85 years: 3 LDOPA after AMD, 1 L-DOPA before AMD. We also examined an independent patient cohort, a subset of the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area (approximately 100,000 people), consisting of approximately 17,500 individuals with more complete EMRs. The same trends were noted in the 20 patients in this cohort with both AMD and L-DOPA in their EMR: 14 received L-DOPA after the AMD diagnosis; 1 received L-DOPA in the same year; and 5 received L-DOPA before the AMD diagnosis. Figure 1 summarizes the combined data for patients from both cohorts, PMRP and the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area subset (n = approximately 37,500). Thus, our study shows that AMD and Parkinson’s disease (or L-DOPA Rx) occur more frequently together than if they were independent, even after stratifying for age. As illustrated in Figure 1, for our combined cohorts, the average L-DOPA Rx age is 67.2 years, 4 years younger than the average AMD Dx age (71.3 years), similar to other studies. Just as in the PMRP subset, the expectation is that we should see more individuals with an L-DOPA Rx before an AMD Dx in individuals who have AMD and have taken L-DOPA at any time. However, again the opposite pattern is seen: the vast majority have taken L-DOPA only after an AMD Dx (Z score 4.627; P <.001), implying that L-DOPA is protective against AMD. Most intriguingly, shown in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 1, the AMD Dx age is significantly skewed in the 10 people who had an L-DOPA Rx before the AMD Dx (79.3) compared with the 44 people who had L-DOPA after the AMD Dx (71.3), demonstrating that the AMD Dx was significantly delayed in people taking L-DOPA before getting AMD (t test: 3.567; P <.01).

Figure 1.

Age distribution of subjects in the Marshfield Clinic Cohorts. The data summarize the age distributions for a first prescription (Rx) for L-DOPA (n = 314), diagnosis (Dx) of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (n = 1795), or a record of L-DOPA before a diagnosis of AMD (n = 10). Errors bars represent the 95% confidence interval. *P <.01 by t test analysis.

Table 1.

Age of Onset Summary

| Study Group | Individuals | Age of L-DOPA Prescription (y) | Age (y) of AMD Without L-DOPA (n) | Age (y) of AMD With L-DOPA (n) | Age (y) of Neovascular AMD Without L-DOPA | Age (y) of Neovascular AMD With L-DOPA | Age (y) of AMD With Dopaminergic Agonists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMRP | 20,000 | 67.1 | 71.2 (1,142) | 79.3 (10) | |||

| MESA | 17,500 | 67.2 | 71.3 | ||||

| TruvanMarket Scan | 15,215,458 | 68 | 71.4 (679,574) | 79.3 (12,387) | 75.8 | 80.8 | 73.9 |

AMD = age-related macular degeneration; MESA = Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area; PMRP = Marshfield Clinic’s Personalized Medicine Research Project.

Our age distribution of AMD Dx and L-DOPA Rx fits the known national pattern,34,35 and so we expect to see more individuals with an L-DOPA Rx before an AMD Dx. We performed a binomial test (Equation 1) with a conservative null model assumption in which only half of L-DOPA Rx cases will be before AMD Dx. We also conservatively assumed that only 44 of the 54 individuals had the L-DOPA Rx after the AMD Dx (ie: we categorized the 7 individuals for whom the L-DOPA Rx date was effectively indistinguishable from the AMD Dx). The resulting conservative P-value for observing 44 or more individuals from the 54 total under these assumptions was 1.7E-06, which is highly significant. We conclude that because the actual P-value of the data is more highly significant than the conservative one calculated, these data offer compelling evidence that there is substantial skewing of AMD Dx dates to later than the L-DOPA Rx dates than one would expect.

| (1) |

Equation 1 Binomial test equation used to determine significance of age distribution for Marshfield Clinic datasets.

Truven MarketScan cohort

To further examine the possible protective role for DOPA on AMD, we performed a similar retrospective analysis using the Truven MarketScan outpatient databases from the years 2007–2011 (Truven Health Analytics). These are the largest insurance claim-based proprietary databases in the United States, containing medical insurance claim records of more than 87 million unique individuals. The de-identified and anonymized data provided by MarketScan databases include demographic and medical diagnosis information. The Outpatient Prescription Drug databases provide data regarding the medications used (both generic and brand) by each patient (in the form of National Drug Codes) and the dates in which medications were dispensed to patients. Figure 2 summarizes our statistical analysis of the MarketScan cohort. In the subset of patients with a record of ophthalmology-related diagnosis, we found that the mean age at first recorded AMD diagnosis in patients not treated with L-DOPA (n = 679,574) was 71.4 years, in agreement with both cohorts from Marshfield Clinic and in agreement with AMD incidence statistics.34 Thus, although we do not have complete medical records, this cross-sectional cohort matches other population-based AMD incident characteristics. We also examined the mean age of L-DOPA prescription in all of MarkestScan databases to determine whether that matched population-based statistics and the Marshfield databases, and found the average age of L-DOPA prescription was 68 years, again similar to the Marshfield Clinic cohort and national averages. These data are summarized in Table 1.

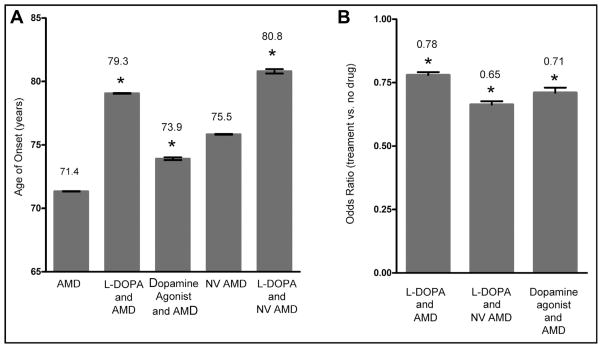

Figure 2.

Data from the Truven MarketScan database illustrates that L-DOPA both delays age-related macular degeneration (AMD) onset and reduces the risk of developing AMD. (A) Data represent the age of AMD onset in several groups, with error bars representing the 95% confidence interval. The AMD group represents our control individuals that had no record of movement disorder prescription history. The L-DOPA AMD group represents all individuals with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) code for AMD that also had a prescription history for L-DOPA. Neovascular (NV) AMD represents individuals with the specific ICD-9 code 362.52 but no history of L-DOPA prescriptions. The L-DOPA and NV AMD group is similar except that the individuals had a history of L-DOPA prescriptions. The dopamine agonist group represents individuals who had a prescription history for various movement disorder drugs, largely dopamine agonists. All groups were significantly different from the AMD control. *P <.001. (B) Odds ratio analysis to determine whether the drugs alter the probability of developing AMD. All values below 1, representing the control, AMD with no L-DOPA or movement disorder prescription history, indicating a reduction in the probability risk of developing AMD, either in general or specifically NV AMD. Each reduction in risk was significant. *P <.001.

Having verified that both AMD age of onset and L-DOPA prescription ages match expectations, we investigated the intersection of those populations. As illustrated in Figure 2, the mean age of first AMD diagnosis in patients with an L-DOPA prescription record was 79.3 years (n = 12,387), and this was significantly later than in individuals without an L-DOPA prescription, 71.4 years (P <.001). Using multinomial logistic regression, we found that after controlling for age and gender, patients with a prescription history of L-DOPA were significantly less likely to have a diagnosis of AMD (OR 0.78; CI, 0.76–0.80; P <.001). Importantly, this finding was also carried through with diagnoses of neovascular AMD (ICD-9 362.52). After controlling for age and gender, and excluding patients with a record of neovascular AMD before an L-DOPA prescription history, we found that age of onset of wet AMD without L-DOPA was 75.8 years, whereas neovascular AMD onset in those with an L-DOPA prescription history was 80.8 years, and this difference was significant, P <.001. Further, the OR suggests that patients with a record of L-DOPA were significantly less likely to have a diagnosis of neovascular AMD (OR 0.65; 95% CI, 0.65–0.69; P <.001). Although we suspect that the positive trophic environment developed by increasing retinal pigment epithelium secretion of pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) may account for protection from AMD via GPR143 signaling, a corresponding decrease in VEGF secretion from the retinal pigment epithelium is also possible.28 The combined effect of increased PEDF, a potent antiangiogenesis factor,36–38 and decreased secretion of VEGF may act together to reduce neovascular AMD.

We also examined whether this effect was specific for L-DOPA by testing for a potential relationship between patients taking other movement disorder drugs. These drugs are dopamine receptor agonists, largely targeted at the D2 dopamine receptor. As shown in Figure 2, we found a small but significant delay in AMD onset in this group, which developed AMD at 73.9 years (CI, 73.73–74.10 years; P < .05). The OR for this group is 0.71 (CI, 0.70–0.73; P <.001). When compared with the age of onset with no drug (71.34 years) or L-DOPA (79.26 years), this was significantly different than both (P <.05). In our previous studies of GPR143, we showed that dopamine and L-DOPA, closely related molecules, compete for the same GPR143 binding site,27 suggesting that dopamine receptor agonists developed for movement disorders may cross-react with GPR143. However, it is also possible that other dopamine receptors are participating in the effect we observed. We also examined this in the Marshfield databases but found no effect on AMD onset or OR for any other movement disorder therapies.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study of 3 independent cohorts, we show for the first time that, of patients with a history of both AMD and L-DOPA use, most received L-DOPA after an AMD diagnosis, in contrast to the expected opposite trend given that the mean age of L-DOPA prescription is years earlier than AMD onset. Furthermore, those who went on to have AMD were diagnosed with AMD at a significantly later age than those who had no record of taking L-DOPA. These results were the same for both dry AMD and neovascular AMD. These data strongly support a protective role for L-DOPA in AMD pathogenesis. Our experimental design does not allow us to specifically assess the mechanism of action of L-DOPA on AMD incidence. GPR143 is the only known receptor for L-DOPA,27,28,39 and signaling through GPR143 simultaneously increases PEDF secretion while decreasing VEGF, providing a plausible biological explanation for the ameliorating effect of L-DOPA on the retina. Normal aging in the retina includes both reduced pigmentation,40,41 the source of L-DOPA, and retinal PEDF.42 Our results may also explain the racial differences in AMD frequency and suggest that pigmentation, a surrogate for GPR143 activity, may be protective from AMD. Pigment epithelium-derived factor levels are significantly lower in vitreous and Bruch’s membrane of eyes with neovascular AMD,43–45 further suggesting an imbalance between retinal pigment epithelium secretion of PEDF and VEGF as part of AMD pathology.45–47 Importantly, our data suggest that GPR143 signaling, a component of both pigmentation and PEDF/VEGF pathways, could be manipulated pharmaceutically to prevent or delay AMD pathogenesis. Finally, the drug to manipulate GPR143 signaling exists, has been used by millions for 50 years, is safe, and is available as a low-cost generic. Our data indicate prospective clinical trials to determine whether L-DOPA can prevent AMD are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was partially supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants UL1TR000427 and 1U01HG006389-01, The Wisconsin Genome Initiative and the Marshfield Clinic (Marshfield Clinic); P30EY001931, UL1TR000055, The Edward N. & Della L. Thome Memorial Foundation, (Medical College of Wisconsin); NIH Center Core Grant P30EY014801 (Bascom Palmer Eye Institute); BrightFocus Foundation and unrestricted grants from Research to Prevent Blindness to the University of Arizona and Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.

The authors thank Jeff Joyce for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: BSM is an inventor on an approved patent for the use of L-DOPA to treat or delay age-related macular degeneration, and has received no income from this patent.

Authorship: All authors participated and approved this submission.

References

- 1.Li YY, Jones SJ. Drug repositioning for personalized medicine. Genome Med. 2012;4:27. doi: 10.1186/gm326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roden DM, Xu H, Denny JC, Wilke RA. Electronic medical records as a tool in clinical pharmacology: opportunities and challenges. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:1083–1086. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya’ale D, et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:844–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, Ianchulev S, Adamis AP. Age-related macular degeneration: etiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:257–293. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handa JT. New molecular histopathologic insights into the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:15–50. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e31802bd546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jager RD, Mieler WF, Miller JW. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2606–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngondi J, Ole-Sempele F, Onsarigo A, et al. Prevalence and causes of blindness and low vision in southern Sudan. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bressler SB, Munoz B, Solomon SD, West SK Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) Study Team. Racial differences in the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) Project. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:241–245. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rein DB. Vision problems are a leading source of modifiable health expenditures. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:ORSF18–ORSF22. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner LD, Rein DB. Attributes associated with eye care use in the United States: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1497–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frick KD, Kymes SM, Lee PP, et al. The cost of visual impairment: purposes, perspectives, and guidance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1801–1805. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Zhang X, et al. Forecasting age-related macular degeneration through the year 2050: the potential impact of new treatments. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:533–540. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rein DB, Saaddine JB, Wittenborn JS, et al. Technical appendix: cost-effectiveness of vitamin therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:e13–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rein DB, Saaddine JB, Wittenborn JS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of vitamin therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1319–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rein DB, Zhang P, Wirth KE, et al. The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1754–1760. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maguire MG. Comparing treatments for age-related macular degeneration: safety, effectiveness and cost. LDI Issue Brief. 2012;17:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein R, Klein BE, Knudtson MD, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in 4 racial/ethnic groups in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein R, Chou CF, Klein BE, Zhang X, Meuer SM, Saaddine JB. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:75–80. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E and beta carotene for age-related cataract and vision loss: AREDS report no. 9. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1439–1452. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Writing Group for the AREDS2 Research Group. Bonds DE, Harrington M, et al. Effect of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and lutein + zeaxanthin supplements on cardiovascular outcomes: results of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:763–771. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heimes B, Lommatzsch A, Zeimer M, et al. Long-term visual course after anti-VEGF therapy for exudative AMD in clinical practice evaluation of the German reinjection scheme. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:639–644. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer CH, Holz FG. Preclinical aspects of anti-VEGF agents for the treatment of wet AMD: ranibizumab and bevacizumab. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:661–672. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovach JL, Schwartz SG, Flynn HW, Jr, Scott IU. Anti-VEGF treatment strategies for wet AMD. J Ophthalmol. 2012;2012:786870. doi: 10.1155/2012/786870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amoaku WM, Chakravarthy U, Gale R, et al. Defining response to anti-VEGF therapies in neovascular AMD. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:1397–1398. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmier JK, Halpern MT, Covert DW, Delgado J, Sharma S. Impact of visual impairment on service and device use by individuals with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:1331–1337. doi: 10.1080/09638280600621436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levinson DR. Medicare Payments for Drugs Used to Treat Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration (OEI-03-10) Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of The Inspector General; 2012. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez VM, Decatur CL, Stamer WD, Lynch RM, McKay BS. L-DOPA is an endogenous ligand for OA1. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falk T, Congrove NR, Zhang S, McCourt AD, Sherman SJ, McKay BS. PEDF and VEGF-A output from human retinal pigment epithelial cells grown on novel microcarriers. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:278932. doi: 10.1155/2012/278932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarty CA, Wilke RA, Giampietro PF, Wesbrook SD, Caldwell GM. Marshfield Clinic Personalized Medicine Research Project (PRMP): design, methods and recruitment for a large population-based biobank. Personalized Med. 2005;2:49–79. doi: 10.1517/17410541.2.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenlee RT. Measuring disease frequency in the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area (MESA) Clin Med Res. 2003;1:273–280. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.4.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seddon JM, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and age-related macular degeneration in women. JAMA. 1996;276:1141–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Mark M, Nijssen PC, Vlaanderen J, et al. A case-control study of the protective effect of alcohol, coffee, and cigarette consumption on Parkinson disease risk: time-since-cessation modifies the effect of tobacco smoking. PloS One. 2014;9:e95297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thacker EL, O’Reilly EJ, Weisskopf MG, et al. Temporal relationship between cigarette smoking and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;68:764–768. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256374.50227.4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomany SC, Wang JJ, Van Leeuwen R, et al. Risk factors for incident age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from 3 continents. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1280–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rascol O, Brooks DJ, Korczyn AD, De Deyn PP, Clarke CE, Lang AE. A five-year study of the incidence of dyskinesia in patients with early Parkinson’s disease who were treated with ropinirole or levodopa. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1484–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machalinska A, Safranow K, Mozolewska-Piotrowska K, Dziedziejko V, Karczewicz D. PEDF and VEGF plasma level alterations in patients with dry form of age-related degeneration–a possible link to the development of the disease. Klin Oczna. 2012;114:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haurigot V, Villacampa P, Ribera A, et al. Long-term retinal PEDF overexpression prevents neovascularization in a murine adult model of retinopathy. PloS One. 2012;7:e41511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boehm BO, Lang G, Volpert O, et al. Low content of the natural ocular anti-angiogenic agent pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) in aqueous humor predicts progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia. 2003;46:394–400. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Locke CJ, Congrove NR, Dismuke WM, Bowen TJ, Stamer WD, McKay BS. Controlled exosome release from the retinal pigment epithelium in situ. Exp Eye Res. 2014;129:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiter JJ, Delori FC, Wing GL, Fitch KA. Retinal pigment epithelial lipofuscin and melanin and choroidal melanin in human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarna T, Burke JM, Korytowski W, et al. Loss of melanin from human RPE with aging: possible role of melanin photooxidation. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tombran-Tink J, Shivaram SM, Chader GJ, Johnson LV, Bok D. Expression, secretion, and age-related downregulation of pigment epithelium-derived factor, a serpin with neurotrophic activity. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4992–5003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04992.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuoka M, Ogata N, Otsuji T, Nishimura T, Takahashi K, Matsumura M. Expression of pigment epithelium derived factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in choroidal neovascular membranes and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:809–815. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.032466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holekamp NM, Bouck N, Volpert O. Pigment epithelium-derived factor is deficient in the vitreous of patients with choroidal neovascularization due to age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:220–227. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhutto IA, McLeod DS, Hasegawa T, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in aged human choroid and eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pons M, Marin-Castano ME. Cigarette smoke-related hydroquinone dysregulates MCP-1, VEGF and PEDF expression in retinal pigment epithelium in vitro and in vivo. PloS One. 2011;6:e16722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pons M, Marin-Castano ME. Nicotine increases the VEGF/PEDF ratio in retinal pigment epithelium: a possible mechanism for CNV in passive smokers with AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3842–3853. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]