Abstract

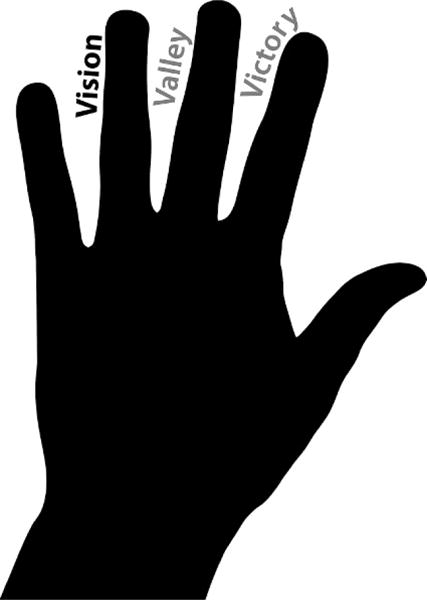

The Vision stage is the development of the agreed-upon framework for the study, including identifying the issue, the community, the stakeholders, and major aspects of the approach. Achieving the Vision requires planning through a Framing Committee, agreeing on a vision by sharing perspectives and identifying commonalities or “win-wins” that hold the partnership together for community benefit, and evaluating the emergence of the Vision and the partnership. Here, we review tools and strategies.

Keywords: Community-Partnered Participatory Research, Community Engagement, Community-Based Research, Action Research

Introduction

Developing a Vision is the first stage of a Community-Partnered Participatory Research project. While all stages are critical to success, in some respects the Vision is the most important because it sets the stage for all that follows: what is to be done, why, and the value of the work from the perspectives of different individuals and agencies. Without agreement on a Vision, individuals and agencies can be at odds or pull in different directions. Given the diversity inherent in community-academic partnerships, the Vision grounds the project, is a cornerstone to resolving tensions, and a source of inspiration for all involved. It is the heart of the project.

A Vision can be defined as the large idea underlying the project. It can also describe its purpose and specific goals. A Vision can include a framework or context for the project by describing: what the issue is; how it came to the attention of the participating partners; the history of the issue in both the community and academic partner institutions; what is known about the issue in the community and the academic literature; and how this particular issue relates to other important concerns of the community and academic partners. The work of the Vision stage is to develop the large idea, ground it in the work and perspectives of the partners, bring additional partners to the table who contribute to its selection and shaping, understand the context for the issue and history for the partners, and outline options for obtaining feedback to refine the issue through partner and broader community input. We refer to this process as framing.

Framing is a complex concept that involves a process of relationship-building, discovery and consensus development and, it is clearly its own work phase. In Community-Partnered Participatory Research, framing is never a simple matter of two or three people deciding on the project in a top-down fashion. The participatory partnership process is central to developing a Vision, and to the overall partnered approach to the project within the Vision stage (and, for that matter, in all stages). If an issue is pre-selected and pre-framed, it can be difficult or impossible to recover a true spirit of equality in decision-making.

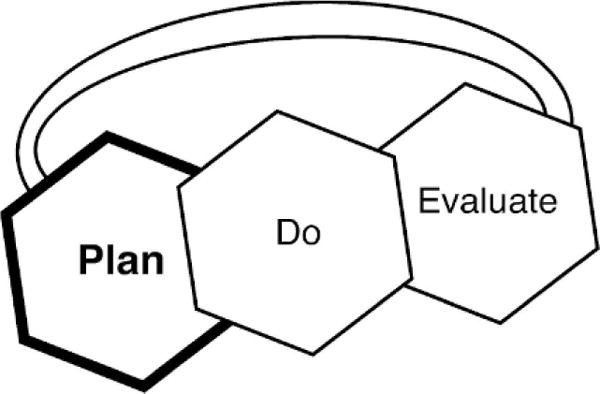

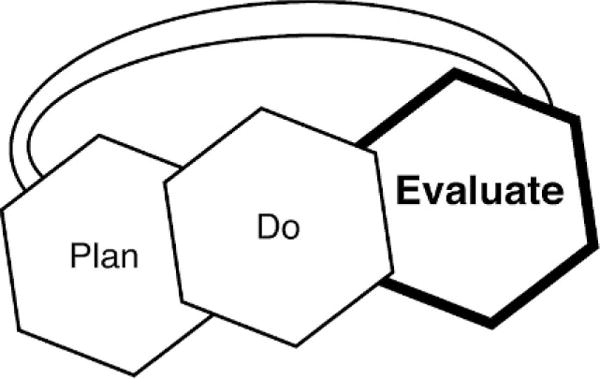

Below, we discuss and illustrate the activities at the Vision stage within the structure of the “plan-do-evaluate” cycle.

Plan

Planning is necessary to set up the process by which the Vision will be developed, and to develop the resources, partnership and information base to select and set the context for the Vision.

Planning involves several key tasks. Each can be the starting point for further planning, provided that all key tasks are undertaken. The tasks are:

Set up a planning structure (including the Framing Committee, working groups, and the community at large).

Define the community for the potential initiative.

Decide who should be at the table for planning, given an understanding of the community.

Develop specific planning goals (this includes clarifying and developing resources for the initiative, and developing an agreement on the partnership principles).

Each is briefly discussed below.

Set Up a Planning Structure

Community-Partnered Participatory Research initiatives have three main structural elements: the Framing Committee, working groups, and the community-at-large. (Also see Circles of Influence in Chapter 1).

Framing Committee

The Framing Committee is a small group, typically between 5 and 10 members, who plan and launch the initiative and provide leadership throughout the project. The Framing Committee should include equal representation of community members and researchers, and should be co-led by one or more community members and an academic researcher.

The Framing Committee should include a diverse set of researchers and community members. It can be useful to include members with whom you have worked before, but be sure to guard against exclusivity. Community members should be “bridge builders”; that is, community leaders who understand and embrace the goals of the coalition and who can encourage other community members to become partners as well. Qualities to look for include enthusiasm for community improvement, the ability to constructively address resistance, strong relationships with community members and organizations, and the willingness to commit time to the intervention. (Note: As outlined in “Guiding Principles for Community-Partnered Participatory Research” in Chapter 2, both researchers and community members should be paid for the time devoted to the project.)

The Framing Committee will evolve throughout the project. At the Valley stage, the Framing Committee, with additional partners, becomes the Council that supports implementation efforts.

Working Groups

Working groups should include a diverse set of researchers and community members, all of whom have embraced the Vision. Working groups are responsible for specific tasks. Usually, members of the Framing Committee also serve on one or more working groups. The size of these groups can vary. Whenever possible, each working group should be co-led by an academic researcher and at least one community member. Working groups may or may not be necessary at the Vision stage but are critical in the Valley stage.

Community-at-large

This includes those members of the defined community that are not a part of the Framing Committee or working groups. Both the Framing Committee and the working groups must keep the larger community informed about the intervention and its progress, provide ways for the community to give feedback, and encourage involvement. The project should provide support and resources to keep the intervention alive and relevant to the community.

Define Community

Defining community is a critical part of Vision planning (although continuing flexibility is important: the process of defining the community may be refined throughout all stages of the project). The definition of community will guide who should be involved in framing the project.

There are many ways of defining a community, and the definition may vary with other features of the Vision, such as the issues being addressed, the partners bringing an initiative to the table, or the history of the issue in the community. We found that there is no universally applicable definition of community. Defining community is a dynamic process that emerges from planning (and may continue throughout the project); but, the planning process begins with a first cut at a definition.

A community may be based on a common characteristic, such as religion, ethnicity, or income level. For example, an initiative may arise from concerns of a particular cultural group, such as recent immigrants concerned about access to healthcare, or a group of pastors wanting to offer social services to community members in their area. A community may be defined by shared interests or concerns, such as individuals interested in improving housing or neighborhood safety. A community may be defined by a common communication channel, such as persons reading a newspaper, sharing a bus or train route, or an Internet chat group. A neighborhood or geographic area is a common way of defining community in community-based initiatives and in research studies. There are other ways of defining a community, and all of these examples would be suitable to an initiative that addresses the concerns of these “communities” and others relating to them.

Regardless of how community is defined, the partners should guard against a definition that is too limited. For example, a definition based on neighborhood in a large urban setting may be problematic because people may cross neighborhoods for different services. A definition based on ethnicity or religious group may be problematic if the issue, such as violence, cuts across groups within an affected geographic area.

We have found that for many health initiatives, a useful definition of community combines both geographic and social network elements: a community consists of persons who live, work, or socialize regularly in a given area. Thus, a given individual may be a member of multiple communities, and those who live in a community share their community with others who have a regular presence in the community. Researchers who work in and with a community are also members of that community.

This definition of community emerged in our discussions with groups of community stakeholders who reflected on a sense of co-ownership of their community with others they worked or worshipped with, whether or not they lived in the community. This definition encompasses many others and is broad enough to encourage participation from a wide range of community partners.

A portion of your planning efforts should be dedicated to considering options for how the community of interest is defined. There is no one answer. Generally our experience is that the community members in the planning process should be given the lead for defining the community, with academic partners available for comment or consideration of implications given the strengths and histories that they offer to the partnership process.

Decide Who Should Be at the Table

As the process of defining the community unfolds, the first question to ask is: Who is to be involved? Who are the key partners for planning, both on the community and academic sides?

Who is included affects many aspects of the Vision: what potential issues may be important, who the other community partners may be, what resources are brought to the table, and what impact the project may have, for whom. Deciding who to include in a Framing Committee is a balancing act between: 1) representing a broad cross-section of the community and having an open table, while 2) simultaneously ensuring a manageable planning process. However, beware of making the group of people at the table too small. The greater risk is not having enough diversity at the table and not mobilizing enough community support or resources that could help the project. Given that community-academic partnered research can be a lot of work, a good general policy is to create an open table, actively recruit a diverse planning group, and give people interesting things to do as part of planning. If too many limitations are set too early, the restrictions can limit the availability of resources or set up a tone of exclusivity that damages the broader community value of the project.

Most importantly, initial membership decisions should create a sense of equal access for all. For example, you can safeguard against exclusivity by including individuals from different sectors, ethnicities, and social advocacy groups to check and balance the planning process. In general, anyone in the community who is willing to work on improving the community’s quality of life is qualified to be a working group member.

The strength of the Framing Committee is the sum of the capacities of its members. Seeking a broad representation of active members and maintaining an open door are critical to success. This can mean actively recruiting sectors not immediately present. Here is where having a definition of community, developed earlier in the planning process, can be especially valuable. You are now in a position to ask: Who needs to be at the table? Who is here already? Who is not?

Academics can help ask these questions, but most typically, community members who are participating will have a sense of who could be helpful at the table. Then a process can be set up to approach individuals and organizations and build some awareness of (and, hopefully, the beginnings of support for) the project within the community. The approach to those individuals should be partnered (both academics and community members should participate). The goal is to ensure that the partnership as a whole, not just individuals already known to the community, develops a growing capacity to engage community stakeholders.

In thinking of stakeholders to include and to encourage their participation, it is useful to think of the possible benefits of participation. Community engagement is a win-win situation for all participants, so collaboratives must be mindful of identifying wins for all stakeholders. Examples of such benefits are outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1.

Potential Incentives for Participating in Engagement Activities

| Community at-large |

|

| Community-based organizations |

|

| Business community |

|

| Hospitals |

|

| Government |

|

Table 3.1 can be used as a guide to find more specific incentives for particular types of organizations. For example, schools and faith-based agencies might be convinced to participate if they see a potential benefit for their primary mission. Schools may desire to have greater parental or other community involvement in education programs; whereas faith-based leaders or members might particularly care about social justice or a sense of spirituality and commitment in the community. Across different stakeholders, the balance of goals, incentives and resources can make for a rich bed of support for the project.

Partners can share their goals and help each other throughout the project. For example, a community initiative addressing violence prevention might help reduce school children’s anxiety, make it safer for people to use public parks or transportation, or lower hospital death rates. Clarifying incentives and identifying potential ways that organizations can benefit can help bring needed partners to the table. Each partner will help shape the Vision, which, like the Framing Committee, will grow and develop over time. As the Vision evolves, it will sometimes become clear that there are still important partners who are not yet at the table. Identifying and reaching out to these partners is a continuous process and will occur throughout the course of the project.

Develop Specific Planning Goals

Core responsibilities of the Framing Committee at the Vision stage, apart from framing the broad Vision for the initiative, are: to clarify and develop resources for planning and subsequent stages; and to develop an agreement on partnership principles that can guide the planning process. These activities should be included as ongoing agenda items.

Clarify and Develop Resources for the Initiative

Many Community-Partnered Participatory Research initiatives have a very broad potential scope, such as seeking to eliminate or significantly reduce neighborhood violence. This broad scope could involve many people working together over many years to achieve success. When partners come to the table, whether from community or academic perspectives, they typically want to know how often they will meet and for how long (what the commitment is), and what will be required of them and their agency in terms of resources. They may have to negotiate terms of their participation with someone else (an agency leader, their family), and balance their participation with other commitments in their life.

An early task of planning for an initiative, as the Framing Committee forms, is to clarify initial expectations and tangible resources available. Are there funds to pay people for their time? There should be funds for community members unless prohibited by their agency, just as there is salary support for academic members. Are there funds to support staff or pilot projects? Are funds available to compensate agencies for contributions they make, or is such compensation expected “in-kind”? Are there funds for research components, such as payments to participants in surveys or focus groups? Will such funding be sought? These and other questions about resources, timeframe, and expectations for the project overall, and the Vision phase specifically, should be posed early and repeatedly, clarified by the leadership, and made transparent to members.

Depending on available resources, decisions may need to be made about how to keep participation broad and equitable. For example, in one phase of our Witness for Wellness project, due to some limitations on funds for community member payments, the Council overseeing the initiative decided to limit stipends for community members to cover participation in one work group per individual per month. (Fortunately for the project, a number of individuals voluntarily chose to participate in multiple groups without additional compensation, but this level of volunteerism should not be expected or taken for granted.) Funding should be regularly monitored by the Framing Committee, or the project can develop a reputation for not having realistic expectations or for taking advantage of people. If funds are not available, initial expectations for work should be modest and the search for additional funding should begin immediately.

Develop an Agreement on the Partnership Principles

Chapter 2 outlined values and operational principles for community-academic partnered research. These values and principles should be reviewed as part of the planning for the Vision stage, so that from the outset all who become involved understand the “rules of engagement” for this form of partnered research. We found it extremely helpful to develop a detailed Memorandum of Understanding, signed by all partners, that documents the principles that guide the project and the rules of engagement that ensure the principles will be followed. We have also found it helpful to develop a project-specific “Orientation Manual,” so that as new members joined the project, they not only understood the origins and history, but also had a summary of partnership principles that they then could see in action in meetings (for example, community-academic co-leadership and equal voting on major decisions). The discussion of principles should begin with the first meeting of the Framing Committee.

Do

Frame the Issue

With a structure in place, the community initially defined, a process set up to bring people to an open table, resources initially clarified, and partnership principles discussed, the main work of the Vision stage is ready to begin: a detailed framing of the issue and its context. This work is actually a continuation – the initial work on framing the issue will have begun from the first meeting and is perhaps the single most motivating factor for initiative participation.

The issue, or overall goal of the initiative, should be one with both community and research relevance. There are different ways of arriving at an issue and setting its context and history, and no one rule applies. Most arise because of either a concern of the community (for example, the hospital closed; there’s a problem with our water or air; school violence has increased) or a history of findings from research groups (for example, we have successful depression interventions and would like to learn how to get them applied in the community [this was how our project, Witness for Wellness, began]).

Sometimes, an issue is defined because partners want to work in a certain way. For example: we want to work on an important issue that also builds a collaboration between the police and the schools; or we want to learn how to apply a quality improvement framework to a community issue. It can be helpful for the Framing Committee to anticipate that there can be both a direct approach to issues (this is what’s important to us) and an indirect approach through the process of building an infrastructure (this is the kind of partnership we want to develop), and that both are legitimate starting points. In both cases, however, the framing of the issue emerges from the Framing Committee discussed above, within the context of the experience of the defined community.

This approach differs from the more traditional “top-down” approach to community involvement, which at best seeks limited advice from a community board. The more traditional approach often defines an issue based on a needs assessment, an identification of a problem, performed by researchers. The needs assessment focuses on a deficit-based model (finding unmet needs). The researchers then develop hypotheses or predictions of cause and effect, propose interventions and evaluate them. At some point the researchers may involve community members to test feasibility or to recruit subjects.

The funding process and the academic promotion system, which rewards independent scholarship and leadership rather than contributions to the community or team membership, drives this traditional approach. Normally, potential funders (both government agencies and private foundations) expect to see the research hypothesis, rationale, background, needs assessment, methodology and planned evaluation techniques before they decide whether or not to award funding, which can span a two-year process during which the community is not engaged. The result: the project is planned, usually with limited community involvement, long before the work actually begins. At this point, it is too late to develop a true community-academic partnered project. However, the researchers may ignore or simply be unaware of the problem, because partnership over time is not a traditional research priority. The researchers do the project, publish findings, and move on to the next project (probably addressing a different issue in another community).

Within a Community-Partnered Participatory Research initiative, we promote a shared process of defining an issue and its context and developing from the broader issue a set of specific objectives and action plan that are valued by and co-implemented (or even largely implemented) by community representatives with academic support. Under this model, it is important for the leaders to tolerate the frustration of it taking time for issues to be defined in terms that are valued by the community—whether initiated from the academic or community side.

For example, in the Witness for Wellness initiative, the initial idea of focusing on depression came from a 10-year history of academic research that carried significant implications for underserved communities. However, the process of exploring whether this was a fit for a community-partnered initiative involved months of shared discussion with a Framing Committee, in which concepts of depression were shared, examples discussed, and controversies over treatment approaches explored. Framing Committee meetings also included presentations from knowledgeable academic and community providers, testimonials from consumers, visits to local institutions concerned with community history, car rides through neighborhoods, and other fact-finding and relationship-building activities. This process led to a strong agreement, after community input, that depression was an important but seldom-discussed priority. That realization led to the framing of the issue as engagement of a diverse community in considering and taking action on the problem of depression. That is a very different framing of the issue than the initial goal of determining how to implement evidence-based depression care for each individual who suffers from depression. In essence, community input helped broaden the issue to include community action.

As the example above illustrates, issues come to light either because they are specifically proposed by concerned individuals, or through a more systematic process of engaging a partnership and community to outline priorities and select among them the best candidates for taking collective action. Either way, the initial set of potential issues is considered, explored, and brought back to the fuller community for input and a “temperature reading” on its importance and what kind of action might be good both short-term and long-term.

Key processes involved in framing the issue are: Discovery (fact-finding, or assessment); Community Check-Point; and Preliminary Issue Definition.

Discovery (Fact-finding or Assessment)

The word discovery suggests that different approaches are valued as ways of identifying potential issues, depending on what methods work and are acceptable in the community. Discovery can occur when experienced leaders “listen” to members of the community at-large or to academic investigators, and hear an issue that may be of promise to build new capacity for the community. Discovery may occur when members of an agency or the community at-large develop a passion or are concerned about an event, and talk to others they know about how to make a difference. Discovery can start with research findings, as researchers search for implementation opportunities. Sometimes, funders are concerned about an issue and put out calls for research or community action.

Within an established partnership, discovery can occur through a systematic process, such as an assessment of local community priorities for health-related action. More systematic methods of discovery include: community surveys; discussion groups or focus groups; stakeholder interviews; review of newspaper or magazine clippings, maps; or observations of neighborhood risk factors. As partnerships evolve and are sustained across multiple projects, a variety of methods of discovery may be used at different times to identify potential issues.

For Community-Partnered Participatory Research initiatives to take hold, however, regardless of the initial discovery method, the potential issue or issues should be advanced quickly by community leaders for informal check-ins with representatives of the potential community that may be involved. For example, community leaders or representatives could host a breakfast meeting and invite 10–20 people from the community to chat about an issue.

Questions that may be relevant to pose at such informal check-ins include: What do people think of the issue? What does it mean to the community? Is something already happening on this issue? What language is used by community for this problem? Are there special concerns about how to approach this area? Are there new opportunities for making a difference or creating change?

Based on initial feedback, the project leaders may have an informal sense that an issue with common appeal to community members has been identified. The idea is not to claim broad representativeness of opinion, but to determine if this is an issue that leaders and community members, who have not necessarily been preselected to hear about a particular issue, can identify with and see as relevant. Not all issues for partnered initiatives need to be broadly appealing; some may be seen as important only to a select population that is directly affected. In general, however, a partnered research project thrives best when the average community member can see its relevance, even if the community member is not directly affected. Many health and medical issues fall into this category.

The next step is to define the issue further, understand its meaning and relevance to different stakeholders, clarify incentives of stakeholders to address the issue, and learn about the history of the issue for the partners, and for the community of interest.

This is a good time for a more formal Vision exercise. The goal of a Vision exercise is to stimulate awareness of common elements, as well as differences in perspectives on both the meaning and the central issue and on the desired outcomes of a project among the diverse members of the Framing Committee. Other goals are to build relationships among members of the Framing Committee, and to set the stage for commitment to the project by clarifying similarities and differences in incentives for participation.

Examples of the underlying questions to pose include: Who are the relevant stakeholders for this issue? (examples: community agency, community at large, policymakers, academics). What is the meaning of this issue, from the perspective of each stakeholder? What are the outcomes that could be achieved by addressing this issue, from the perspective of that stakeholder?

These questions can be asked of the specific stakeholders present—but that can put pressure on a given stakeholder or increase the sense of “we-them” by focusing too much on group differences (for example, in resources) at an early stage. Another approach that we more commonly use to avoid this problem is to ask each Framing Committee member to answer the question for each type of stakeholder; then we arrange the answers by stakeholder type (rather than by specific respondent). This exercise asks each member to put themselves in the shoes of each of the relevant types of stakeholder, and imagine the issue or outcome from that stakeholder’s perspective.

As a group, we then can examine what we have learned about the issue, incentives, and outcomes for each stakeholder. We talk about differences and similarities, and define what a “winnable” issue is from diverse stakeholder perspectives. Alternatively, we break the large group into subgroups, where each subgroup describes the perspectives of a given type of stakeholder and reports back to the large group. In this way, everyone becomes involved and can problem-solve in teams within the Framing Committee, building relationships while allowing people to focus on a manageable portion of the input.

This kind of visioning exercise can be very effective, and should be conducted so as to be engaging for all participants. We have used a variety of approaches to keep things fun and level the playing field. For instance, we have used different colored yarns to represent different stakeholders or different issues, and ask people to throw the yarn (while holding a piece) to another member to pose the relevant question (about the issue or stakeholder), alternating their throw with that of another member who starts with another color of yarn (about another issue or stakeholder). As the exercise proceeds, a network of colored yarn forms around and over the table, showing the interconnections of stakeholders and issues, tangling everyone in a connected web of multi-colored yarn, and making the Visioning exercise more entertaining.

Puppets can be very effective in encouraging discussion. Each puppet becomes a stakeholder “character” with a specific point of view. People speak in the voice of the puppet (often using a distinctive funny voice for that puppet) to share that stakeholder’s perspective. We have found that people reveal more emotion (such as anger or awareness) in play than they might without the puppets. Sometimes, people get so engaged, it’s hard for them to return the puppets after the meeting!

We also use a story, an adapted version of the Grimm Brother’s tale Stone Soup, in which people bring different assets to the table and show how we need each other; this can be incorporated into the Vision (the strengths we have to address the problem).

As the project uses different approaches to develop and shape the Vision (the issue and its history in the community), the findings or story should be documented. The array of stakeholder perspectives, for example, can be documented in a table or in meeting notes. Graphical representations are very helpful to quickly convey complex ideas. As the meetings continue and the Vision becomes clearer, with stakeholder perspectives, meanings, story, and context all shared, the group develops a history that is available to all members of what the “issue” means, why it was selected, how it plays out in the community, and what the initiative is likely to mean when presented to the broader community. This history should be documented through a manual, website, or other means in order to share it with new leaders who enter the project, or with members of working groups in the Valley stage, thus, familiarizing newcomers with the original concept of the Vision.

Along the way, it is possible that the Framing Committee will decide to engage in a more formal process of assessment, more typical of a needs assessment in academic research projects. A systematic assessment might involve a community survey, set of formal stakeholder interviews, or focus groups. If these activities emerge from a Vision stage and have broad community support, they may then constitute a main project (a discovery project) that can have its own Vision, Valley, and Victory stages, leading to a next (intervention) project.

In vulnerable populations, needs assessment without action often may be unpopular or seem exploitative, so we tend to encourage a more engaging and focused assessment effort to frame a CPPR project, followed by a rigorous primary project designed to do something about the issue.

As the sharing process proceeds, some particularly salient exchanges will occur. Sometimes conflict flares up or emotionally touching moments occur in the group. These “hot spots,” whether within the Framing Committee or among members outside of formal meeting time, are extremely important for leaders to identify. They present new opportunities for partnership growth or Vision clarification. Typically, such “hot spots” are signs that an important issue is being discussed. Both the strong feelings and the perception that an issue is important can be useful in framing the issue. Leaders should not be afraid of strong emotions and should learn to value authentic, constructive interactions as important signs of the potential of the project.

In the Witness for Wellness initiative, for example, academic and community members of the Framing Committee became aware that each group defined depression differently. Academic members were more focused on a clinical view of depression as a diagnosable psychiatric disorder; community members were more focused on a social and community view of depression as emerging from community stresses and victimization. In one memorable meeting, an academic member read aloud a poignant letter received from a participant in a research study about her experiences with life struggles and depression, and cried while reading the letter. A strong bond emerged between community and academic members over a new sense of shared vision for working together to relieve the burden of depression.

Regardless of how the initial Vision is developed, the members of the Framing Committee should use a strength-based approach in exploring issues and framing the issue context. Developing a Vision should be a positive experience for the community (regardless of the issue) while building capacity for community planning. Not all interventions developed under a community-academic partnered framework will be effective, but the process of developing and evaluating the intervention should be effective for bringing hope for improvement and developing a community leadership capacity for health improvement.

Community Check-point

Host an early meeting where community members can listen to your initial ideas and provide feedback. At this meeting, hosted by the Framing Committee, community members should voice what they would want to achieve by participating in the project. This process can unite members of the group, involve them in achieving a solution, and help build the community or organization.

The community meeting can have different kinds of settings, purposes and structures, depending on the nature of the issue and its history in the community. The more challenging the problem, the more thought may need to be given to the key step of obtaining community input. For example, a sensitive topic such as depression might require an initial step of input through a breakfast meeting of community members, or a more intermediate step of a workshop with, say, 50–70 community members and leaders, followed by a larger community conference (our first community depression conference had more than 400 community members). On the other hand, a more commonly discussed problem such as diabetes, with less-associated social stigma, might proceed directly to a major conference in a high-profile venue.

The structure of conferences is important to obtaining useful community feedback. For example, it is important to share with the community some of what was learned in the planning efforts, so we typically include several presentations, by community and academic members, on information about the issue, summaries of what we’ve learned in the discovery phase and visioning exercises, and something engaging such as a short film. A large group presentation of this nature, which also introduces the members of the Framing Committee and features their diversity in leading the project, can be coupled with small group breakouts where the main input is obtained. For the Witness for Wellness initiative, a one-day conference was held. The morning was spent in presentations, a lunch was provided, and the afternoon was spent in breakout sessions in which community members offered their perspective on depression and how to address it. Documenting the input is important, through notes either by staff or community members or both. Audio or video taping may be a possibility to share the process with others who cannot be present. You will need to obtain written permission of attendees for any recording, and ensure that those who do not want to be recorded can still participate.

Community input may also be obtained through innovative means, such as hand-held audience response systems where the results are immediately posted and shared with the audience (anonymously of course!). This method, which is used in popular television shows such as “Who Wants To Be a Millionaire?” can create an atmosphere of fun and shared participation. We used this approach for a community feedback session for the Witness for Wellness initiative, with the result that an otherwise gloomy subject was presented in an engaging manner, with music between presentations and other features such as small gifts and information brochures, to give the audience something to take away with them. For such events, we ask local merchants to donate food, movie tickets or small gifts.

Regardless of how the feedback is obtained, the Framing Committee should assure that the input is documented, synthesized and reviewed in a transparent manner. The feedback session is not about rubber-stamping a pre-developed agenda, but about truly determining whether and how this issue or set of issues can engage the community in order to proceed to the next stage. Further, a community feedback conference at this stage offers both an opportunity to celebrate the work so far, and is a major venue for recruiting working group members for the Valley phase. For example, from the first Witness for Wellness community conference, which had more than 400 participants, about 90 were recruited as active working group members, including the community leaders of all working groups.

Conferences of this nature are also an important opportunity to bring in policy leaders to become part of the process, as well as academic institutional leaders to support the academic partners. This can become the starting point for a community and academic policy advisory board that supports the main phase of the project. Such leaders should be given a visible role, such as providing a welcome or giving a quick greeting.

Preliminary Issue Definition

Based on what has been learned, the Framing Committee then proposes a preliminary definition of the issue and may also have enough information to propose a preliminary intervention or set of action plans leading to an intervention. To do this, the Framing Committee reviews what it has learned from the summaries developed for the community feedback session and discusses the feedback from that session, such as survey results, themes from breakout groups, and committee members’ own impressions of reactions and comments. What have they heard? Is there broad community support, or only for a certain portion of the problem, or for a certain step? Where are the vulnerabilities and who is most vulnerable? Are there political sensitivities? Do leaders seem supportive both in the community and in academic institutions? Are there special opportunities at hand, such as an agency (a school system or faith-based agency) with resources to initiate a project? Is a partnership of that type desirable and feasible? Or would it go in a different direction than that supported by the community?

After considering such questions, the Framing Committee is likely to have a sense of what the issue is, in language used by and familiar to the community, that will engage the community in action that can be supported broadly in the community. They will likely have a list of interested players for working groups, and may have a sense of the likely work domains or even of a potential intervention that represents an achievable first step. They may have a sense from the discussion of the capacities that need to be built, and the special community or academic opportunities, and if so, the time frame for taking advantage of them.

The Vision stage often ends with a call to action for a new initiative that has been developed through the partnership and is community-owned. If leaders have been thoughtful and lucky, they may have a sense of likely funders to approach for the main phase.

The final set of activities in the Vision stage include: setting up the structure of the next phase, specifying the mission or broad goal for each specific working group; and branding the initiative, for example, through a title, logo, or other public representation that reflects the mission and honors the community’s voice. Having a clear charge for working groups helps link the next stage to the mission, and branding helps the initiative gain traction in the community.

The Vision stage will probably last approximately 3 to 6 months, with 1–2 additional months for follow-up on the community feedback and transition to the main project working groups. Although this may seem like a long time, this time period is actually minimal for the tasks that need to be accomplished: building trust among members; listening to the community; establishing good relations with a wide variety of community groups, organizations, and individuals; identifying community issues and strengths; sharing perspectives and learning about context; obtaining community feedback; and synthesizing it all into an issue, mission project image, and scope of work.

Evaluate

As with other aspects of the initiative at each stage, the evaluation activities should be partnered, with community and academic co-leadership. Evaluation is critical at the Vision stage for: 1) framing and using the data from visioning exercises; 2) identifying and describing the characteristics of a defined community; 3) synthesizing information on what has been done about a problem, what exists in the literature, and the current status of the issue in the defined community for the initiative; 4) specifying issues for community feedback and collecting and analyzing that data to frame an issue; 5) describing the process of development of the Vision; 6) monitoring the evolution of the partnership, and (7) determining whether the partnership has achieved authenticity in terms of adhering to its core values and operational principles.

In general, the full toolkit of evaluation methods apply to these purposes, including focus groups, review of historical data, interviews, formal surveys, and other methods. Some excellent texts on how to apply evaluation methods within a participatory research framework include Barbara Israel’s book, Methods in Community-based Participatory Research for Health1 and Meredith Minkler and Nina Wallerstein’s book, Community-based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes.2 In the Witness for Wellness partnership, we spent a full year hosting a “book club” in which this guidebook and other community-academic partnering methods and resources were reviewed. Academic and community co-presenters discussed chapters and articles, and a wide range of team members were present for the discussion. This was an important capacity-building exercise to expand the evaluation methods available to our partnership.

Because projects in the planning phase typically have relatively limited resources, we suggest identifying some commonly used data collection devices, such as slides from presentations, meeting notes, output of literature reviews, brief (one-page) process sheets collected at the end of the meeting about how the meeting went, existing reports, and field notes from field trips/interviews as the primary data. Projects with fuller resources can engage in a more rigorous set of data collection activities at this stage.

Evaluations are typically conducted by having a set of potentially answerable, clear evaluation questions; identifying the evidence or data needed to answer the question; deciding on a design, such as whether groups are compared or simply being described; deciding on a data collection method; and analyzing and summarizing the data.

In a community-academic partnered project, each step in the evaluation process is shared, even though some delegation may occur, depending on the level of time and resources to support capacity building. For the Vision stage of the Witness for Wellness project, for example, we developed an approach that combined meeting minutes with “scribe notes,” which were notes identifying major issues and the emotional tone of discussions, observations of interactions and how questions and answers flowed, and action items for major decisions. The minutes also documented all action items: what is to be (or has been) completed, by whom, when, and the support needed or used. For research purposes, these data sources were used to describe the process of developing the goals for the project as a whole, as well as the content of specific action items.

Many of the activities involved in conducting visioning exercises result in a database to document and evaluate project progress. For example, when we have asked committee members during framing to identify desired outcomes of an initiative from the perspective of different stakeholders, the resulting grid of issues by stakeholder is a dataset that informs visioning and also documents how we arrived at the Vision.

For work that engages communities that have either been subjected to research abuses, or have suffered from discrimination or other forms of social repression, the concept of participation in research and evaluation can be threatening and can have quite negative connotations. These negative connotations can be worsened when the academic participants are from a dominant culture (eg, Caucasian) associated with having supported such abuse, while the community participants primarily represent another culture that is either historically underserved (such as Latino or some Asian American groups), has a history of extensive repression or abuse (such as African American and American Indian), or otherwise has a vulnerable or stigmatized social status (persons with HIV infection, gay/lesbian, vulnerable elderly or young children, for example).

It is important to identify these broad concerns or potential concerns in the partnership or community at-large. Discussions with the community should not be limited to the history of the issue per se. Community discussion, framing, and reviews should cover the proposed partnership and the proposed methods, including research and evaluation.

It may be important to find ways of explaining the benefits research offers. For example, one can refer to commonly available medications, or safety features such as seat belts, and the role of research in making those technologies available. Further, clarifying the histories of abuse and areas of concern that apply to specific populations can be useful, as well as describing the safeguards in place to prevent abuses and monitor the research. Typically at the Vision stage, for example, we have sessions for the partnership on human subjects’ protection issues, and we encourage either community members with extensive human subjects’ protection experience or lead administrators at the academic institutions to act as consultants to review human subjects’ aspects of research and the applicable protections. Active participation of community participants in the design, implementation, evaluation, and reporting of evaluation helps to build the trust in the evaluation.

Evaluations are based on a conceptual framework – what exists, what we’d like to achieve, and how we will achieve it. Conceptual frameworks are very important in research and, since a Vision stage is about identifying an issue in context and describing the history and meaning of the issue to the full partnership, in essence what is being developed is a conceptual framework. Such frameworks may even be informed by formal theories available in the academic sector, as well as by cultural histories and prior beliefs about how things work in the community. For example, an important concept that emerged through review of the scientific literature and from partnership discussion during the early stages of Witness for Wellness was that of collective efficacy, or the power of the community to take collective action to address an important problem like depression. This concept later became the topic of a main research paper from the project.3

We close this section of the Vision stage by offering one conceptual framework for evaluating partnership development in relationship to the community-academic partnered research framework. This model can inform the evaluation of partnership development throughout, beginning with the Vision stage.

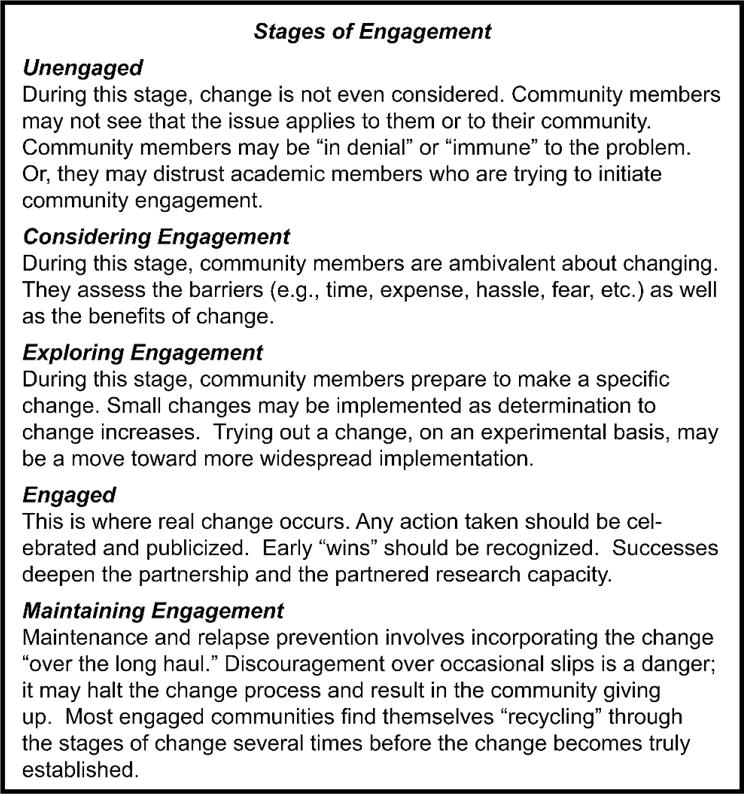

A Conceptual Framework for Evaluating Partnership Development: Stages of Engagement

The goal of a community-academic partnership is to make real, lasting, and empowering changes in the community. Achieving this goal requires an authentic partnership that evolves over time through different stages of engagement. How can a team know what stage of development applies to their partnership? In particular, to complete the Vision stage and enter into the Valley, or main work, is the partnership fully engaged and ready to work?

We propose a model to consider partnership development that was inspired by the Stages of Change Model of Prochaska and DiClement.4

The Stages of Change theory suggests that different factors affect change and lead to the next stage, each having different intervention implications for each stage. For less-engaged partnerships, leaders may need to pay greater attention to developing new relationships, sharing perspectives to build existing relationships, and reviewing areas where collaborations are possible by encouraging the team to discuss possible “wins” or incentives for each potential partner. Matching up partners who have something to offer each other, or aligning partners around issues that match their needs and incentives, are ways of speeding up the engagement process. In addition, greater education may be needed on the expected course of partnership development, or by asking other partnership teams to share what they have learned about the advantages of working together.

At later stages, or with more fully engaged partners, these factors remain important but the emphasis can be placed more on the action plans related to an agreed-upon Vision. Then, partnership development activities might focus on consultation needed to meet technical demands of projects, formalizing understandings concerning sharing resources and credit for products, etc.

Change takes time and requires a major shift in perception. Before change can occur, community members must feel that it is both needed and possible, and that they are in a position to take action. If they are unengaged (no feedback to community at-large yet), community members may be almost unaware of the issue; or, if considering engagement, they may feel that the problem is a fact of life that nothing can alter. During the project, they move toward exploring engagement (developing partnerships, exploring small changes), and becoming fully engaged (working together to take action and celebrating each step).

One of the most difficult steps is maintaining engagement, both in terms of the partnership and building on the work to build sustainable community capacity. It is common and natural for each group to revert back to what is formulaic and familiar. Working through such backsliding is an essential part of the community engagement process. A skilled facilitator is needed to mediate the discussions. For example, a partnership may develop a new level of trust, only to become deeply distrustful in response to an incident that seems minor to one party and not the other. Sometimes, action plans may need to be reformulated to be more engaging or more achievable.

Several examples of this occurred in the Witness for Wellness project. For instance: after more than a year of developing the partnership, framing the issue, and initiating the working groups, community members worked with academics within one working group to select a depression screening tool from several available tools. A formal rating process was established, with community members trained to review measures by consultants who explained their psychometric properties, such as reliability and validity, and the populations included in prior studies. After reviewing this information, almost all the tools were rated as excellent, with one slightly preferred. After the ratings occurred, the academic partners did further work on the costs of using the screening tools and found that the preferred tool involved costs, while others did not. The leadership therefore recommended using one of the other tools. Community members, however, were taken aback that the tool the group had designated as “preferred” had not been selected. The fact that the work on costs was not done in advance, plus the amount of capacity building to enable informed choice by community members, stimulated a sense of distrust and betrayal; community members felt that the rug had been pulled out from under their good-faith efforts. This issue was the subject of considerable discussion that took months of leadership work to resolve.

In retrospect, the “fault” is not the decision, but the lack of appreciation by project leaders of the extent of preparation required to explain the iterative nature of the scientific selection (ie, it is hard to get all of the relevant information together at once, or sometimes one’s thinking evolves through different stages of decision-making, and all of that is part of science decisions). Alternatively, there should have been more thorough homework prior to the rating process so that the selected tool could truly be honored. It is likely that “undoing” the preferred selection also triggered other community feelings about prior research collaboration efforts that generated a sense of distrust in research in general or in particular academic institutions involved.

What we have learned from such events is that they are important signals of when an issue needs attention, requiring all partners to work together to nurture a relationship, redirect power (typically more toward community leadership), increase capacity for more technical work, or solve a policy problem.

To handle such events, which can sometimes feel like an insurmountable crisis, time-outs and mid-course evaluations may be needed, where all parties can be both honest and supportive of each other in re-committing to the change. Leaders should anticipate that such crises are often an inherent and common aspect of partnered research, not a cause for despair.

From the perspective of formative evaluation (ie, shaping an initiative through evaluation feedback), when a crisis occurs, one can turn to the project mission, the project operational principles, the minutes and any “scribe” or field notes to track what had been agreed to, and what action items have occurred. These data points, along with team members’ impressions, allow the team to reflect on what the crisis might mean for course correction. For example, leaders can clarify exactly what the project should be doing, which in some cases might be enough to resolve the crisis, which often arises from a misunderstanding or miscommunication.

Generally, partnered projects should be designed to accommodate a range of expected and unexpected consequences, curves in the road, and time to build on the lessons learned.

Fig 3.1.

Vision

Fig 3.2.

Plan

Fig 3.3.

Watch your language

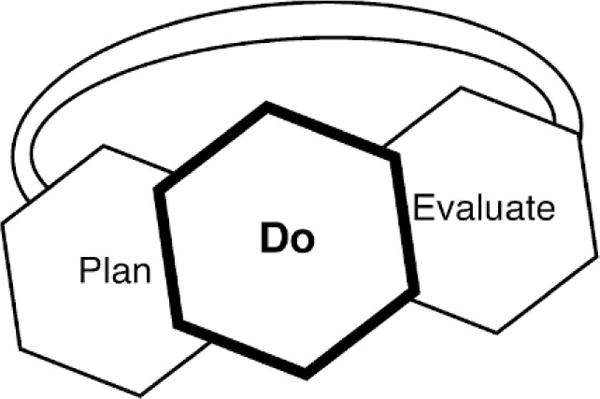

Fig 3.4.

Do

Fig 3.5.

Stone Soup

Fig 3.6.

Begin where the people are

Fig 3.7.

Do your homework

Fig 3.8.

Evaluate

Fig 3.9.

Stages of engagement

Fig 3.10.

Share

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the board of directors of Healthy African American Families II; Charles Drew University School of Medicine and Science; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Reproductive Health; the Diabetes Working Groups; the Preterm Working Group; the University of California Los Angeles; the Voices of Building Bridges to Optimum Health; Witness 4 Wellness; and the World Kidney Day, Los Angeles Working Groups; and the staff of Healthy African American Families II and the RAND Corporation.

This work was supported by Award Number P30MH068639 and R01MH078853 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Award Number 200-2006-M-18434 from the Centers for Disease Control, Award Number 2U01HD044245 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Award Number P20MD000182 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Award Number P30AG021684 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control.

References

- 1.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237–244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psych. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]