Abstract

This first of three chapters on the Valley stage, or main work of a Community-Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) initiative, concerns the planning phase of the work cycle. The main goal of this phase is to develop an action plan, which clarifies the goals, methods, responsible individuals, and timeline for doing the work. Further, this chapter reviews approaches, such as creativity and use of humor, that help level the playing field and assure community co-leadership with academic partners in developing effective action plans.

Keywords: Community-Partnered Participatory Research, Community Engagement, Community-Based Research, Action Research

Introduction

The Valley is the main work of the partnership where you will implement and evaluate the project or intervention you have undertaken (Figure 4.1). The work is hard and one can sometimes feel that one is trudging through it, which is why we call it the Valley. Like all hard work, it can sometimes be frustrating. But, it is also a source of meaning, fun and even joy as partners work to benefit the community, make contributions that they find personally rewarding, and conduct research that informs the community and others of the lessons learned.

Fig 4.1.

Valley

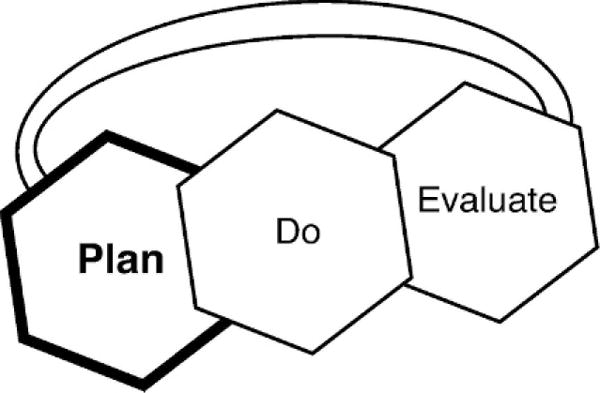

Because the Valley is the most labor-intensive phase of the work, we discuss it in three separate chapters, one each for the three diamonds on the work cycle: Plan, Do, and Evaluate. Plan is described in this chapter (Figure 4.2), Do in Chapter 5, and Evaluate in Chapter 6. Although we discuss each of these steps separately, it is important for both leaders and team members to look at the Valley as a whole and think of overarching aspects of the work that will enhance its success. For example, we cannot overemphasize the importance of the Evaluation stage, which informs every step of the Valley. The evaluation measures you choose will directly influence your planning in the Plan stage and your data-gathering in the Do stage, therefore evaluation measures are actually developed concurrently with each aspect of the project, rather than after the project. We provide some tips based on examples of strategies that helped us succeed in our own Valley. (Figure 4.3)

Fig 4.2.

Plan

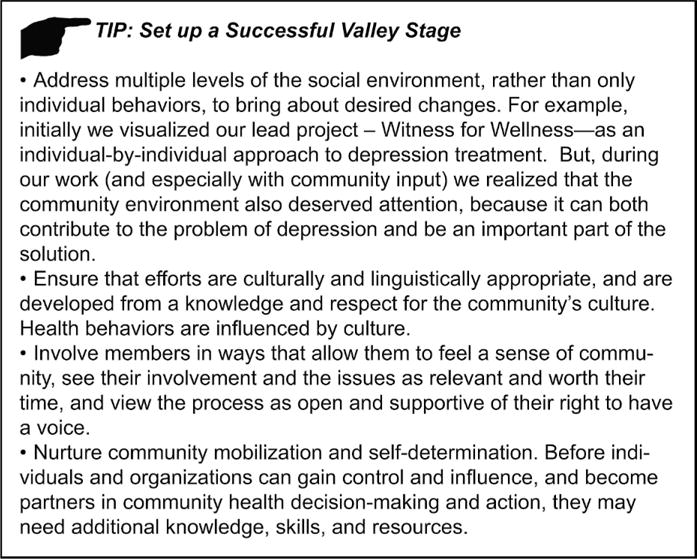

Fig 4.3.

Set up a successful valley stage

In this chapter, we discuss reshaping the Framing Committee into an ongoing Steering Council, which sets up action plans that match the Vision. In addition, because “branding” a study and ensuring partnership development are critical during the planning phase of the Valley, this chapter concludes with two “special interest sessions” on these topics.

Framing Committee or Council Role in Planning

Although the primary work of developing the action plans is that of the working groups, the Framing Committee, now transformed into a Steering Council, plays an important overall role in the planning of the Valley stage.

New Council Structure

Once the job of framing is completed, the Framing Committee should become a Steering Council. The Council might include one or more subcommittees. Examples of subcommittees include an Executive Committee of lead community and academic members who can provide day-to-day support and represent the primary institutions supporting the project; an Evaluation Committee to support developing and implementing the evaluations required for the working groups and the Council; and at a later stage, a Dissemination Committee to handle data requests and policies, and support publications and other dissemination activities.

In addition to Framing Committee members, the Council will include the community and academic chairs of the working groups, and possibly other ad hoc members, such as grassroots community members to help assure ongoing community accountability. This larger group is one reason why an Executive Committee may be necessary to expedite decisions.

Meeting frequency

Regular meetings of the Council will continue through the working group phase. The Council and each working group typically meet monthly, or working groups monthly and the Council every other month, alternating with the Executive Committee. We have used this structure in the Witness for Wellness initiative. To keep the project moving between meetings, we expect Executive Committee members to respond within three working days to emails or other forms of contact to give a vote on an issue.

Responsibilities

The Council and Executive Committee have the responsibilities of attending to the larger Vision of the initiative, developing a mission for each working group, and supporting the working groups in both accomplishing their individual action plans, and integrating their action plans into the whole. Working groups develop their own identity over time, and it is important for all participants to remain part of the larger initiative. If they do not, the execution of the Vision can become splintered.

The Council supports this integration through having report-backs from each working group at each Council meeting, hosting discussions about how the project overall is going, encouraging cross-group discussions, and making Council visits to individual working group meetings. This vertical and horizontal communication is key to project integration.

In addition, the Council can decide to develop a set of action plans that support project integration, or that take on areas of the project not assumed by the working group, such as broader policy and communication issues, or issues that affect the project as a whole. Examples include: raising funds for the project, conducting outreach on behalf of the project, and developing a marketing strategy for project branding. As with the main working groups, those plans should also have community input. Sometimes this can be done informally, such as introducing a proposed project logo and title at a community feedback session and seeing what kind of spontaneous reaction it receives.

Perhaps the single most important function of the Council during this phase is to refine and implement the agreement for the partnership. This agreement, which outlines the project goals, Vision, and operational principles, sets the tone, rules of engagement, and relationship-developing strategies for the working groups and the Council. Issues of partnership development are discussed in Chapter 2.

Developing an Action Plan

After the Vision has been established, a plan of action, which matches the Vision, should be developed and include reasonable timetables.

Developing an action plan focuses efforts and helps to clarify logistic problems. The process of building an action plan must be participatory and involve the Council, working groups, and the community at-large.

The action plan for each working group should specify the following:

Overall goal for that working group

Objectives

Activities

Responsible party

Timeline

Evaluation measures

An example of an action plan for one of the working groups from Witness for Wellness is shown in the Table 4.1. Note that there can be several versions of the action plan—one for initial feedback, one after discussion in the working group and the Council, and a final one after community feedback is obtained and integrated into the plan.

Table 4.1.

Sample Action Plan

| Action Plan | Methodology | Timeline | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruit group members and establish links to relevant groups and organizations. | NM attended local NAMI meeting. KM sent invitation to BDL, DMH consumer rep., will follow-up with her. KM and/or NM will attend the local NAMI Chapter Directors’ meeting. |

Ongoing | All |

| Build cohesion and rapport among group members. | Work on allowing/ensuring that all group members to participate equally. | Ongoing | All |

| Develop a fact sheet about group to be used for promotion and member recruitment. | PY, in collaboration with NM, drafted a fact sheet. Sheet was circulated to group members for feedback, and will be revised accordingly. Once completed, fact sheet will be distributed to local and state policymakers. |

February–March 2004 | PY, with input from group. |

| Develop links to policymakers in LA County and State offices. | Using the fact sheet, group members will contact policymakers and inform them of our goals and activities and try to identify areas for collaboration and resource sharing. | Ongoing | All |

| Get informed about mental health policy and people/organizations in the field who could be potential collaborators. | Gather and review materials. Develop a directory/library/binder of resources. Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health Disparities was circulated to group members. Identify local organizations and/or individuals who are involved in health policy (e.g., MC at USC; Community Health Councils; DMH client coalition). |

Ongoing | All |

| Inform community about mental health policy and resources. | Develop a glossary of terms regarding policy for community. CB will identify someone who can assist with the glossary. Identify and distribute useful materials. |

Ongoing | All |

Organize trainings for group and community:

|

Group members will identify representatives from different organizations who could conduct the trainings (CB will work on Policy 101 training, KD will look into having someone from DMH lead a training, KM will look into someone from UCLA’s Community and Media Relations to conduct a training on Media Advocacy). | March–August 2004 | All |

| Brainstorm and share passions about what topics group will address. Rank and prioritize ideas. | Group has discussed various policies that would be an appropriate focus. Continue to share ideas and begin to narrow focus. UCLA research assistant will begin to search for policy gaps and/or policies that aren’t working. |

January–June 2004 | All |

| Present topic ideas to the community and get community’s feedback on goals and future activities of group. | Formulate a list to be distributed to community participants at future trainings and report back meetings. | At community trainings and at Report Back to Community in July 2004 | All |

| Based on community feedback, develop 2–3 action items for group and community; 2–3 policy goals and a media strategy for dissemination and advocacy. | July–August 2004 | All | |

| Identify potential funding sources and seek funding. | CB suggested approaching the California Endowment about their private/public partnership grants. | Ongoing | All |

Action plans should be updated periodically to meet the needs of a changing environment, including new community opportunities and possible emerging opposition to the proposed intervention. An action plan, although written, is a dynamic document that can and should change, with the required levels of approval, to meet changing circumstances and to accommodate what has been learned so far. Consider taking the following steps to develop an action plan.

1. Organize a brainstorming meeting with the working group and the community at-large

Key community representatives and the working group should brainstorm on specific actions to implement the intervention. This brainstorming activity can be similar to the activities described for the visioning exercise – but the starting point is the mission for the working group, which should already have been set by the Framing Committee or Council. Given a mission (which can of course have suggested rewording and reframing by the working group and Council), the brainstorming session encourages people to think both “in the box” and “out of the box” (Figure 4.4). Ask questions such as:

What does this mission mean to you?

How can we do it? What do we need to get done?

How are other people doing this or things like this?

Think out of the box: What new strategies should we use that fit our community?

Fig 4.4.

Think outside the box

The brainstorming can be facilitated using the same types of tools as were used in the Vision exercises—stories, poster boards for writing up brainstorming, puppets, balls of strings, games—anything that is community-friendly, levels the playing field, and gets people thinking and sharing creatively.

Brainstorming sessions can be followed by work that all partners, both academic and community, complete away from the meeting. This is a critical part of each team member’s commitment to the project. (See Chapter 5 for a more complete discussion.) Assignments should be kept to about one or at most two hours, and might include: Tape record some ideas; call three friends to ask what they think about a specific issue or idea; do research in the library or on the Internet; write down a list of activities that would fill a gap in the action plan or do a literature search that addresses some of the ideas developed in brainstorming.

2. Develop a draft for the action plan

Answering the following questions should help the working group design action plans that fit the mission of the group and are feasible (ie, can be reasonably expected to be achieved within the group’s scope and resources).

Does the plan

Give overall direction? The action plan should point out the overall path without dictating a particular, narrow approach. For example, suppose the working group feels that their skills in a particular area should be enhanced. The action plan should list “skills enhancement” in this area as an objective, without specifying a particular skills training program. The working group will later decide collectively on the appropriate program or programs to achieve the objective, perhaps based on the groundwork of one or more members.

Match resources and opportunities? A good action plan takes advantage of current resources and assets, such as people’s willingness to act or a tradition of self-help and community pride. It also can embrace new opportunities such as emerging public initiatives to improve neighborhood safety or economic development efforts in the business community.

Minimize resistance and barriers? When one sets out to accomplish important things, resistance (even opposition) is inevitable. However, action plans need not provide a reason for opponents to attack the initiative. Good action plans attract allies and deter opponents.

Resistance within the group can be a sign that the action plan needs further attention. For example, in the Building Wellness working group (one of the working groups for Witness for Wellness), several action plans were proposed through brainstorming to improve the quality of services provided to patients. Community members were particularly concerned with improving screening for depression (by educating community case workers about depression). Academic clinicians in the group were especially interested in improving provider know-how (by improving clinical care programs in neighborhood clinics). Both were reasonable ideas, but the community members thought that the group needed to have more experience with local services and to develop relationships with local providers before taking on the issue of improving services at the provider level. In other words, the provider-level action plan was not a good starting point for the group in the context of the community. In this case, “resistance” was an important clue as to how to reframe the plan. Working together, the group changed the plan to focus on supporting case workers to educate clients about depression care and facilitate referrals to providers. The reframing kept the spirit of the mission, but yielded an action plan that the group wanted to implement and one that would lead to a next step.

Reach those affected? To address the issue or problem, action plans must connect the intervention with those who should benefit. For example, if the purpose of the intervention is to reduce unemployment by helping people obtain jobs, will the proposed activities (such as providing education and skills training, creating job opportunities, etc.) reach those currently unemployed?

Advance the mission? If, for example, the mission is to reduce unemployment, are the proposed actions enough to make a difference in the unemployment rates? Or, if the mission is to prevent or reduce a problem such as substance abuse, have the factors that contribute to risk (or increased protection) been changed sufficiently to have an effect?

It can be helpful at this stage to spend time thinking about how proposed action plans will affect the desired outcome for the chosen population. Action plans may be good plans even if they address a problem indirectly, provided that the indirect influence is strong. An example is addressing a concern about healthy eating habits of schoolchildren through programs that reach teachers, cafeteria workers or parents. In this case, people other than the children are the indirect influences, but their influence can be expected to be strong. The related logic model would clarify that the working group is pursuing the goal of healthier eating on the part of children through the actions of the adults around them.

3. Design do-able objectives

We want to develop and carry out action plans that are do-able and thus prove their effectiveness through concrete results. Wherever possible, early achievements or victories should be designed into the process to show the group members and the community that positive changes can occur. For the near term, devising short agendas of do-able tasks will prevent the partnership from spreading itself too thin. For the long term, focus on creating impact and sustainability. Review the action plan periodically during the process to accommodate changing circumstances and community needs.

A common method used to develop do-able objectives is “SMART” (ensuring that the objectives are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-sensitive).1 However, we felt it was necessary to expand this approach to match the Plan-Do-Evaluate model. Therefore, we suggest that SMARTIE objectives be used to structure the action plan. SMARTIE is an acronym for:

| Specific | Identify what results are expected |

| Measurable | Indicate quantitative/qualitative measurements |

| Achievable | Outline what is achievable, given time and resources |

| Realistic/Relevant | Ensure that objectives are realistic and fulfill high-priority community needs |

| Time sensitive | Include expected time for completion |

| Inclusive | Allow all those interested to participate with equal weight |

| Engaging | Engage as many members of the community as possible; ensure that the process of developing objectives and action plans is inclusive. |

Including SMARTIE objectives in the action plan will encourage a diverse set of community and academic members to review, plan and provide feedback to the process. This is particularly important as part of the next step: reviewing the whole plan, the wording of each item within it, and developing a readable, clear and complete draft.

4. Check your proposed action plan for completeness, accuracy and whether it contributes to the Vision

Things to consider are:

What are the working group and community at-large willing to do to address the problem?

Do you want to reduce the existing problem, or does it make more sense to try to prevent (or reduce risk for) this problem in the future?

Does the plan reach those at-risk for the problem?

How will your efforts decrease the risk? How will your efforts increase protective factors?

Does the action plan affect the whole community and problem? A strategy that focuses too narrowly on one part of the community often isn’t enough to improve the situation, and could be dismissed as just another “Band-Aid.” Make sure that your strategies affect the problem or issue as a whole, or lead to that end, even if that will take many steps. In other words, are the action items, individually and collectively sufficient – will they do the job?

Are all of the action activities necessary? Can some be eliminated?

What resources and assets exist that can be used to help implement the action plan? How can they be used best?

What obstacles or resistance could make it difficult to achieve your mission? How can you minimize or get around them?

Who are your allies and competitors?

This phase of rigorous review can be conducted first by the working group or by a designated subcommittee. Sometimes it can be helpful for working groups to include a Council member or two, who can comment on how these action plans relate to others being proposed. Other working groups may be addressing similar issues. This came up in the Witness for Wellness initiative, when two of the working groups initially wanted to address the issue of stigma in the community for those suffering from depression, along with related policy suggestions. Action plans were coordinated (one group focused primarily on educational activities to reduce stigma, and the other on policy changes), and then the groups helped each other by collaborating on action plans. That coordination occurred through their regular reports at meetings of the Council, and then negotiating trade-offs with leaders of both working groups with the support of the Council.

5. Present the action plan back to the community and make any desired adjustments

The final word on whether action plans are acceptable comes from the community at-large. The same kind of forum for engaging the community at this stage can be used at the formative stage of framing the Vision—a larger, open meeting, with engaging ways of presenting plans (for instance, using music, a stage, hand-held audience response systems or other ways of getting and giving feedback quickly). We have used brief skits or comedy to present the mission of each group, more formal presentation of slides for action plans, outside moderators or entertainers to make sure that they are presented in an engaging manner to the community and in language that the community can understand, and a variety of ways of hosting vote-taking for plans as a whole or for each working group.

Depending on the size of the community forum, there may be time for discussion as well as voting, and members of the working groups should remain available to further discuss the issues informally after the voting sessions with community members. We also provide small thank-you gifts such as movie tickets, tee-shirts or cups (which, if at all possible, we try to get donated for the event), and have some form of refreshment. We usually have information available on the health condition under discussion, and ways that people can sign up to become involved in the ongoing project. In this way, community feedback is an ongoing way of replenishing and broadening working group membership.

At this stage, when the community at-large is actually voting on action plans, it is important to prepare participants, whether academic or community, for the impact of the vote. After months of hard work, participants may not be prepared for critical feedback—and it does not always happen that the community supports whole-heartedly even the most carefully developed plans. For example, a working group may decide that the priority population for a particular health problem is women; but the community may be uncomfortable with this limitation, and may want an equally strong focus on men. A process should be developed for collecting and analyzing feedback, whether given verbally or in writing.

Each working group and the supporting Council should then develop a response to the community, by either directly incorporating the feedback or negotiating a change. If the working group feels the community suggestion is not do-able (beyond the project’s scope and resources, for example), the working group should develop an alternative solution and negotiate it with the Council and representatives of the community at-large. In general, we try to literally follow the main suggestions that arise from community members at this key stage in the process, because the value of community input and support is very high.

Qualities that help ensure success

Dr. Joe White, a pioneer in the field of African American psychology, noted in the February 23, 2006 African American Mental Health Conference in Los Angeles, that much community engagement work requires the seven tenets listed below. We have found these to be very useful in working together through a Valley. The seven tenets are: improvisation, resiliency, connectedness to others, spirituality, emotional vitality, gallows humor, and healthy suspicion of the message and the messenger. We provide brief descriptions of how the seven tenets work in our Witness for Wellness initiative.

Improvisation

The idea for use of puppets in our work arose from a childhood interest of an academic partner, who spontaneously arrived at a meeting with a few puppets to see how they would affect the interactions. They have been very successful in most settings. However, they are not uniformly useful; we have learned that they can be less successful in settings accustomed to a more formal meeting protocol. Community members have been very spontaneous in making academics feel at home (hugs, etc.), and academic members have responded at later meetings (bringing home-grown fruit or home-baked cookies). These spur-of-the-moment gestures have greatly facilitated relationship building for our work together.

Resiliency

The strength-based approach (focusing on strengths and assets rather than deficits) builds resiliency. We support actions such as apologizing for mistakes and then moving on. We expect strong feelings to be expressed and encourage people not to take offense and to have faith in the intentions and work of others.

Connectedness to Others

We have retreats and picnics, call on each other to help out family members or provide other ways of support, and invite each other over to our houses or host meetings in friendly locations.

Spirituality

We have worked hard to respect diversity of approaches to spirituality and to honor particularly the importance of the spiritual domain of life in constructing our community interventions. For example, we frequently collaborate with clergy to host key meetings in faith-based settings.

Emotional Vitality

Academic styles of engaging in committee work are seldom described as “fun” or “full of life.” To counteract this nose-to-the-grindstone attitude, we ask members to rotate leading an engaging activity at each meeting. We have developed a style where humor is used freely and often. In fact, sometimes when phone conferences are used to allow more members to join a meeting, there is so much noise in the room that people on the phone cannot hear through the talking and laughter (so we just tell them they need to show up instead).

Gallows Humor

Gallows humor is the ability to find amusement even in a situation that seems dire. To date, the experts on the gallows humor are our community partners, but perhaps our academic partners will join them in a later phase of our partnership growth. Frequently, a good laugh can make even a dire situation seem a lot more manageable. (Figure 4.5)

Fig 4.5.

Gallows humor

Healthy Suspicion of the Message and the Messenger

We have learned to respect healthy suspicion and to value it as an important contribution to our work. For example, at a recent policy advisory board meeting for a project, a policymaker who was attending that meeting expressed doubt about the value of treatment for depression from a community perspective, compared to policy action for social justice. A long discussion followed that helped develop a whole new approach to talking about that project in the community and the related policy goals.

Creating and Promoting Your Brand

A brand is the intervention’s identity. It can include the name, logo, tagline, color scheme, and position or placement of message. An effective brand tells the community who you are, what you do, and how you will do it. The brand will influence how community stakeholders perceive the intervention. If the brand has a high perceived value, it will help create a demand for the intervention and increase recognition and funding, and help ensure the intervention’s success. The appropriate working group should create promotional materials, get community feedback on the branding, and develop and execute a promotional plan.

The promotional materials will depend on the communication strategy called for by your promotion plan. Promotional materials could include flyers, brochures, posters, ads and public service announcements, toolkits and websites, among others. You might also consider selecting spokespersons or setting up a “speaker’s bureau” to promote the intervention with accompanying slides, PowerPoint or other presentation materials.

The goal is to get the attention, support, and involvement of the community. Think through:

How many different groups are you aiming to reach?

Should publicity material be produced in different languages or perhaps in large-type format? Should the material be modified to appeal to different age groups? Should various media such as TV, radio, and newspapers be used?

When is the best timing for publicity and information to ensure optimal response?

Do you want a start-up promotion approach (aiming for a large number of quick responses), or a more sustainable approach where the emphasis is on building community commitment over time?

Are there fluctuations or seasonal demands for the proposed intervention? How will the group manage the surge in interest during busy periods, as well as the lesser demand during slow periods?

Do you need different promotional strategies? For example, a targeted meeting aimed at a specific group will not require broad promotion. Instead, you will probably contact potential attendees by telephone or in person. Larger meetings, workshops, conferences, on the other hand, will require a commitment to broad promotion.

Consider pilot-testing your promotional tools and involving responses from individuals in different sectors, such as marketing, health, education, and business. Their expertise can assist in tailoring your message.

A promotional plan describes the media, tools and tactics you plan to use. Some examples of promotional vehicles include using existing listservs, databases, email distribution lists, media (such as print, TV, live interviews, radio), along with forming solid, reliable, and authentic partnerships in the community to help maintain visibility and presence. Table 4.2 displays examples of promotional missions and tools.

Table 4.2.

Examples of tools and tactics to promote your initiative

| If your mission is to: | Then tools or tactics might be: |

|---|---|

| Create awareness of the risks of low birth weight among women of child-bearing age in Los Angeles | Advertise in exercise clubs, nail salons, and grocery stores. Distribute promotional tools to obstetricians. Offer free baby care seminars to expectant mothers. Request airing of public service announcements on local radio stations. |

| Reduce teen pregnancy | Sponsor events attended by teens. Conduct teen health education presentations. Develop authentic partnership with teens and provide education to create peer-sex educators. |

Fig 4.6.

Share

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the board of directors of Healthy African American Families II; Charles Drew University School of Medicine and Science; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Reproductive Health; the Diabetes Working Groups; the Preterm Working Group; the University of California Los Angeles; the Voices of Building Bridges to Optimum Health; Witness 4 Wellness; and the World Kidney Day, Los Angeles Working Groups; and the staff of Healthy African American Families II and the RAND Corporation.

This work was supported by Award Number P30MH068639 and R01MH078853 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Award Number 200-2006-M-18434 from the Centers for Disease Control, Award Number 2U01HD044245 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Award Number P20MD000182 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Award Number P30AG021684 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control.

References

- 1.Drucker P. The Practice of Management. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1954. [Google Scholar]