Abstract

Much of the work for a community-partnered participatory research (CPPR) initiative is done in committees that operate under the principles of CPPR and the vision of the partnership, while implementing the action plans of the initiative. Action plans are developed in work group meetings and sponsored events that engage the community in discussion about programs or new policy directions. This article provides detailed recommendations for conducting meetings, completing assignments, and running events as the main body of work.

Keywords: Community-Partnered Participatory Research, Community Engagement, Community-Based Research, Action Research

Introduction

The main work of the Valley stage is “Do”: the implementation of the community-approved action plans for each working group, and for the Council as a whole. (Figure 5.1, Figure 5.2) The action plans will likely cover a range of specific activities designed to build a final product or set of products. The action plans should specify reasonable timelines for each activity.

Fig 5.1.

Valley

Fig 5.2.

Do

Working groups take on action items in different ways: sequentially if they need to proceed step-wise or divided into different sub-groups, each co-led by community and academic members when possible. For example, the mandate of the Building Wellness working group of Witness for Wellness was to help community agencies recognize the signs of depression and provide appropriate care. The group broke into sub-groups and focused on: screening for depression; education about depression; making provider referral for depression; and designing an evaluation. After fleshing out these areas, the groups then divided into web-site design and agency relationship development groups. Meanwhile, the co-leaders developed a funding plan and helped all sub-groups coordinate their efforts. Challenges and progress were discussed with the overall Council for the initiative. Sometimes challenges were met by doing additional work outside of the meetings, such as adding co-leaders with special skills. Sometimes challenges were met through facilitating communication, or even suggesting that sub-groups work more independently for a period and reconvene as a full group after completing their specific tasks.

“Do” stage activities included discussing how to do the work in group meetings, dividing up assignments, completing tasks outside of meeting time, and even making field trips to agencies. Assignments were brought back to the working group, where they were reviewed, modified and redrafted as needed.

During this stage, you might consider inviting guest speakers to build the capacity of the group as an addition or an alternative to a meeting. We hosted seminars on policy, listening skills, human subjects protection, as wells as a media training about targeting specific demographics. Often, participating agencies sent members of their agencies to these events as a learning experience, which was also an agency “win” or benefit from the project. These special sessions increase support and resources for the project, and cultivate pride in the importance of the work.

The leaders guide the working groups in selecting appropriate activities, completing them, and integrating them to complete each action plan. Sometimes in the process of the work, action plans are modified or replaced, because part of the work is the dynamic process of deciding what works best to fit the goals or objectives, given the context and resources. One cannot always anticipate the bends in the road up front, so adjustments are needed—and that requires good judgment, flexibility and leadership.

The remainder of this chapter briefly mentions gathering data (discussed in more detail in Chapter 6), and then discusses three main activities critical to the success of the “Do” stage of the Valley: conducting meetings, delegating tasks, and sponsoring community events.

Gathering Data

The “Do” part of the project will include implementation of the intervention or other activity, and gathering the related data. Data gathering is so closely tied into the evaluation methods you will be using that we cannot discuss it separately. Data gathering methods are therefore discussed in more detail in Chapter 6, “Evaluate.”

Conducting Meetings

Community engagement projects, from the initial idea to the implementation to the ongoing evaluation, are team efforts. Teamwork requires meetings. Therefore, successful teamwork depends almost entirely on the team’s ability to conduct successful meetings.

Make It Easy for Community Members to Attend the Meetings

Meetings are often easier for academic members than community members. Once a project is funded, meetings are a normal part of academic members’ work, and are built into their schedules. Community members, on the other hand, must often try to squeeze project meetings into (or after) already busy workdays. The following considerations will help make it easier for community members to attend project meetings. These considerations are also important when planning meetings with the community at-large.

Time

Consider the relative advantages of day time vs evening meetings. Do day time meetings conflict with the daily work of many community members? If so, evening meetings (with babysitting care for small children and transportation for those who need it) should be considered. Meeting length is also important. The meeting should be long enough to cover the material but should not require an overwhelming commitment of time.

Site

Select a venue that is comfortable, easily accessible and large enough to accommodate the number of persons that you expect to attend. Possibilities are agency or business meeting rooms, the public library, the YMCA, the town hall, service clubs, churches, community centers, and schools. Site selection may also be influenced by the type of intervention you choose to address. To avoid confusion, the site should be the same for each meeting. Once the site is determined, decide on how to arrange the room. Circular seating enhances coalition building by assuming equality among group members.

Ensure Coordinated Leadership

Meetings should be co-chaired by at least one academic and one or two community members. These individuals will facilitate the working group meetings. They should work closely to plan each meeting, agree on the action steps that arise out of the meeting, and prepare for the next meeting.

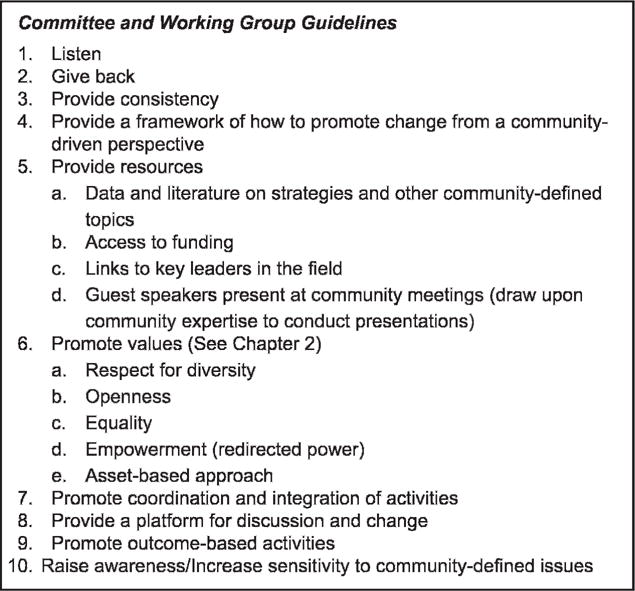

During the meeting, the facilitators will ensure that decisions are formalized by voting, action plans are developed, commitments are made, and that participants feel good about attending. Good facilitators are concerned about both the meeting’s content and its style. Meetings should be not only worthwhile, but enjoyable. The suggestions in Figures 5.3 and 5.4 and the following discussion will help facilitators to conduct successful meetings and face any challenges that may arise.

Fig 5.3.

Guidelines

Fig 5.4.

Tip for facilitators

Welcome Everyone

It is important to welcome old and new members to the table. Membership should be inclusive, not exclusive. New members should feel that the group is open to new ideas and viewpoints.

Allow Members to Introduce Themselves

The facilitators should introduce themselves and explain their role. Icebreakers may be used to begin introductions and help the group begin working together. For example, go around the table and ask each person why they have joined the group and what they would like the group to accomplish. Or, spend five minutes “warming up” with general social conversation.

Establish the Ground Rules and Structure

At the first meeting:

Ask for volunteers for the roles of note taker (responsible for preparing the meeting minutes and keeping a log of attendees) and time keeper (responsible for ensuring that each speaker respects the agreed-upon time limit).

Ask the group to develop guidelines that will ensure a fair and equitable process. For example, will action steps be decided by consensus (arriving at agreement among all members), majority vote, or a combination of both depending on the issue? What is the time limit for each speaker? When and how will the minutes be sent to group members? (Note: we suggest that the minutes be sent out no later than two days following each meeting.)

Provide copies of the pertinent sections of Roberts Rules of Order, and suggest that the group use this as a guide in conducting meetings.

At every meeting:

It is the job of the meeting facilitator(s) to maintain the ground rules. Each meeting should include a quick reminder of key rules. Consistent adherence to these ground rules may not guarantee success in all circumstances, but it will greatly help the process. Ground rules should include:

Listening

One person should speak at a time. This allows members to be heard. Speakers should respect the agreed-upon time limit (and the timekeeper should help them do so).

Shared mission and goals

Once these are developed, they should be adhered to (unless the group decides to formally revise them). The facilitators should remind the group of the shared mission and goals at the beginning of the meeting. Because the group will (we hope) be very diverse, it will include participants with a wide variety of ethnicities, backgrounds and organizational affiliations. As noted in Chapter 2, developing a statement of mission and goals that encompass and respect this diversity is challenging. Even when the mission and goals are agreed on, nearly every meeting will likely present the challenge of balancing individual, group and project interests. The facilitators will sometimes need to encourage a member to set aside individual, ethnic or organizational interests in order to move the project forward. At other times, respecting such interests will be vital. Striking the right balance will require judgment and tact.

Membership

Starting at the first meeting, participation expectations should be addressed. The key membership requirement is willingness to act to better the community. Membership should be open to anyone who is willing to do the work and participate in task forces. Diversity should be encouraged. Willingness to work is completely separate from financial support. Those who support the mission through participation should be defined as members. Those who provide financial support should be defined as sponsors. Over time, membership will probably change. Facilitators should develop tactics to:

Introduce new members.

Make new members feel welcome.

Bring new members up-to-date on what’s happening.

Ensure that information/knowledge is shared between new and old members.

Decision-making

Under a community engagement framework, decisions must be arrived at in a clear, transparent way that allows all interested persons to participate. Avoid behind-the-scenes decision-making. Transparency is best achieved when decisions are made with the participants present, and through the agreed-upon mechanism (eg, consensus or majority vote). If community members feel that their input is not being used to drive decisions, the entire intervention will be perceived as cynical and manipulative, creating an atmosphere of distrust and discouraging further participation. (Figure 5.5)

Fig 5.5.

Maintain a level playing field

Giving back

Data and analyses that are gathered from the community should be reported back to the community, so that the community members can evaluate results and participate in ongoing improvement efforts. All information, decisions, summaries, and reports should be shared with the working group and the community at large.

Review the Agenda

Developing the agenda is a group process. The facilitators should spearhead development of the draft agenda, which should be sent to group members at least one week before the meeting. Input from group members should be requested. The final agenda should be sent to the group at least one day before the meeting.

At the beginning of the meeting – and at the top of the agenda – the specific objective(s) for the meeting should be clearly stated. Every meeting should have concrete, realistic, time-sensitive and measurable objectives that are in line with the overall scope of work or action plan.

The first agenda item will always be the review and acceptance of the minutes from the previous meeting.

Build Trust

For teamwork to succeed, you and your team members must believe that you can depend on each other to achieve a common purpose. Trust is your willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another person based on the expectation that both parties will treat one another respectfully. Community engagement requires the building of trust. Trust can be built through rapport, listening, consistency, and ethical behavior.

Building rapport is the development of mutual trust, harmony and understanding. It requires that all members (community and academic, individuals of different ethnicities, etc.) understand each other’s view of the world. Rapport develops when perspectives, realities, and style of communication are mutually understood. Rapport is the ability to be on the same “wavelength” and to connect mentally and emotionally. Having rapport does not necessarily mean that you agree, but that you understand the other person’s perspective.

You cannot establish trust if you cannot listen. A conversation is interactive. Both speaker and listeners play a part, each influencing the other. Instead of being a passive recipient, the listener has as much to do in shaping the conversation as the speaker. Listeners must pay close attention to the speaker, trying to fully understand what he/she is saying. At the same time, listeners must evaluate how the speaker’s input might affect their own viewpoint and the viewpoint of others in the group, and how it might help move the project forward. Listeners should ask questions and respond to the speaker’s comments. Facilitators should encourage polylogues, not monologues.

Trust is also built on consistent patterns of behavior. Consistency in behavior promotes trust between all team members, and between the team and the community at-large. Consistency includes reliability, dependability and follow-through. Once you have made a decision with community members or commit to doing something, stick with it.

It is essential for those engaging the community to adhere to the highest ethical standards. Past ethical failures (for example, researchers in the Tuskegee syphilis study of the 1930s–1970s withheld treatment to mostly African American males with syphilis) have created distrust among some communities, resulting in great challenges for current community organizers. If there is any potential for harm within the community through its involvement or endorsement of an intended action, the community must be educated regarding those risks so that potential participants can make an informed decision. Ethical action is the only hope for developing and maintaining the community’s trust.

Overcoming Meeting Challenges

Table 5.1 offers a list of common meeting challenges, along with the techniques we have used to face them openly, encourage unity, and move the project forward. We also present more detailed ideas on overcoming each of the challenges.

Table 5.1.

Ideas for overcoming meeting challenges

| Challenge | The facilitators could … |

|---|---|

| One person is dominating the meeting (talking too long and not allowing interruptions). |

|

| Some members are reluctant to speak. |

|

| One person’s comments have become unduly negative, destructive or argumentative. |

|

| New members need to be brought up to speed on the group’s protocols, goals and action plan. |

|

| The more authoritative members are taking over the group (or, possibly, the less authoritative members are too shy). |

|

| The academic and community members have developed into separate “camps” and are sitting in two separate groups. |

|

| Progress is stalemated due to lack of consensus. |

|

| By the end of the allotted meeting time, only a few of the agenda items have been covered. |

|

Ensure Equal Participation

Every person at the table should be encouraged to participate in the discussion. This is especially important in the beginning stages of group development; as the group develops its own rhythm and working style, group dynamics may change to support the momentum.

The facilitators should introduce a topic of discussion to the group, in accordance with the agenda, and should ask open-ended questions to get the discussion started. The facilitators should also set a time limit for each topic, and should remind the group of the time limit for the topic and each speaker. Discussion among group members should be encouraged. More can be accomplished when participants are interacting with each other, not just interacting with the facilitators. Be cautious of asking questions that make either community members or researchers uncomfortable in ways that might be difficult for them to discuss directly. Some examples we’ve observed are: community partners may be uncomfortable with questions relating to their level of formal education. Academic partners may feel uncomfortable with their “squareness,” lack of experience with diverse populations, or the physical style (hugs) of some community partners, and may not be used to questions about their personal lives, such as whether or not they go to church or what their spiritual beliefs are.

Sometimes, sensitivities are difficult to anticipate, but generally the community and academic leaders will know how to frame issues in such a way that team members can provide information without raising undue anxiety or causing people to withdraw. Finally, keep the discussion on topic and directed to the objective of the meeting as much as possible. This may mean encouraging people to explain to the group how their point relates to the agenda item, for example, or clarifying whether a new agenda item might need to be added to this or a future meeting to allow fuller discussion of a new topic.

Respect All Participants

Valuing each person’s opinion displays respect for each person’s personal history, culture, skills, and professional experience. It is important that a facilitator not force his/her personal ideas or opinions on the group. On the other hand, facilitators, like other group members, have the right – indeed, the obligation – to speak up when appropriate. If you are a facilitator and you have a point to make, ensure that the timekeeper monitors your time and that you keep within the agreed-upon limit. Remember that, because you are the facilitator, others may take your comments with extra weight. You should avoid dominating the discussion and, at all times, encourage others to contribute. Another strategy, if a leader wants to be a member for a particular meeting, is to ask another group member to temporarily act as co-chair for that meeting (which can have the additional advantage of building leadership skills across the group).

Emphasize Strength-Based Thinking

When conducting a meeting, it should be explicit that the group values a strength-based learning and working environment. This means that:

Positive affirmations are given.

The facilitators exemplify strong negotiation skills.

Active listening is employed first by the facilitator and then by the members.

Overall respect for each member’s experiential and professional background is given at all times.

The working group should focus on community strengths (rather than community deficiencies) by designing objectives that utilize the assets provided by the team and the community. The assets-based approach uses promotion, empowerment techniques, capacity building, and advocacy. Of course, a realistic assessment of “gaps” or deficiencies is necessary, but the action plan should be designed to enhance and draw on community strengths.

Allow Silence

Silence is a method of communicating. It allows both the facilitators and the group to collect their thoughts, digest the ideas discussed, and prepare for future conversation. Avoid the temptation to jump into every period of silence. After an appropriate time, re-open the discussion – possibly along new lines.

Avoid Jumping into Details at a Finite Level

It is the working group’s responsibility to decide on both global and detailed decisions in support of the overall mission and goals. However, while global decision-making should occur in the group meetings, detailed decision-making can often be undertaken as work outside of the meeting by one or more individual members, who will return to the group with a specific recommendation. After the recommendation is presented to and discussed by the group, a final consensus can be reached. This saves time and keeps the group moving forward.

For example, suppose the group decides that its skills in a particular area should be enhanced, and that outside experts should be invited to speak at a group meeting. The group does not have to figure out who the outside experts are. That task can be designated to a group member (or members) to carry out: investigate experts who can speak on the topic and review their credentials, compile a list, and make recommendations to the group.

Commit to Work Outside the Meeting

To ensure that the agreed-upon objectives are met in a timely manner, members should be aware that there will be times when they will have assignments that they will be expected to complete. Over time, every group member should undertake at least one assignment. Facilitators should avoid allowing the group to break into workers and observers. Assignments will be discussed in more detail in the following section.

Give Thanks

At the conclusion of the meeting, it is important to thank attendees. The facilitators should also review what was accomplished, make sure there is a clear understanding of assigned tasks, and answer any questions that members may have regarding future meetings. The facilitators should remind everyone of the next meeting date, and should follow up with an e-mail or telephone reminder at least one week prior to the next meeting.

Some meetings may be more productive than others, especially in the beginning. It may take time to develop rapport and momentum. Even if the meeting has been less productive than you had hoped, relax and express thanks to the group for getting together. Relationship-building creates the necessary foundation for productive work.

Everyone Is Committed to Work Outside the Meeting

It is a rare group that can accomplish all of its work during meeting time. Working groups require work outside of meeting time to complete action plans. In addition, these tasks encourage ownership of and commitment to the process. Each assignment should be documented in the minutes. Such documentation will specify the person(s) responsible for the assignment, along with the date when the work will be complete and the results reported back to the group.

Expectations will differ for the group leaders (who will probably do more work) and working group members, but should be about equal across the working group members. In fact, an important task for the leaders is to think through assignments that keep members participating and contributing without unduly burdening them. Generally, we ask members to do one to two hours of outside work for each meeting, as their commitment to the project.

Group Facilitators/Leaders

Group leaders have the work of communicating regularly between meetings, in person or by telephone or other form of communication such as e-mail to: 1) review the minutes and action items for each meeting; 2) monitor progress on the action plans; 3) meet with the Council to report progress or request assistance; 4) develop an agenda for the next meeting; 5) communicate as needed with individual members and subcommittees from their working group to support their work, such as helping to clarify tasks or problem-solve meeting challenges. These are the basic assignments of group leaders between meetings, apart from whatever work they have agreed to do on action plans within their group.

Members

Members can be given brief tasks that follow from the work needed to complete action plans. Examples include: visiting a facility, making a contact or two, talking to friends for ideas and writing those ideas down or taping them, recruiting new members to come to meetings, looking up information, or developing creative or artistic ideas, such as designing a logo or making posters or hand-outs for an event. Events require an extra level of effort and coordination from the group, so often preparing for the event may take the equivalent of one or two months of time for a number of group members, all in a few weeks.

For action plans requiring a significant amount of sustained work, such as developing a training program or piloting an intervention, a group of particularly dedicated and available individuals will likely be needed. It will be difficult for the dynamics of the group if this falls primarily to the leaders, and especially if the academic members with more covered time step up to fill in the gaps too much. A better solution is to recruit one or two community members to work with group members, and to find the resources to give them a stipend for the more intensive work. This kind of solution should be discussed with the Council, which can help look for the resources, perhaps within sponsoring institutions. Figure 5.6 presents a suggestion that has been successful with our projects.

Fig 5.6.

Community scholars

Managing the assignments—making sure that they are done, finding alternatives when there are sticking points, integrating them into a whole—requires many of the same skills, and benefits from the same kind of tips for running meetings or operational principles for leading the project or partnership as a whole.

Sponsor Events

Sponsored events hold great potential to move the mission of a working group or the project forward in the community. Sponsored events could include:

Community Forums

Community forums are meetings of the community at-large. For instance, community forums should be used to obtain feedback on the project Vision and proposed action plans, as discussed in Chapter 3. A community forum can also be used to generate feedback on the progress made toward fulfilling action plans, or for feedback on products before they are finalized. We have also conducted community knowledge transfer sessions. Offering something of value to the community can be a highly successful way of developing capacity and spreading the word about the project.

Community Exhibits/Events

Community exhibits are ways of displaying information about the project, and sometimes of obtaining input and conducting research. Exhibits can take advantage of existing community events, such as health fairs, art exhibits, or other broad-based community activities. We regularly piggy-back on such community events to make presentations, host exhibits, provide information, talk to people, and sometimes to conduct surveys or interviews of people who visit the exhibit. We use this information to pilot educational interventions or obtain input on ideas, information, and policy strategies. In this way, we both help to communicate with the community about the project, while also gathering useful information concerning action items.

Different working groups can collaborate on these opportunities. Care should be taken to make sure that these valuable community events are available to several working groups when at all possible, since resources are probably scarce and should be used efficiently across the project.

Large community events require careful planning, and typically require some infrastructure that can manage the event, whether a community organization or an academic organization or both. Even piggybacking on an existing community event requires considerable planning. In our experience, working groups often underestimate the amount of planning and preparation required. It is useful to discuss each event with the project leadership up front, to review the requirements for proceeding to a sponsored event.

At minimal, event planning requires several steps: finding a venue; determining if special insurance is required; having a set-up and clean-up plan; meeting venue requirements for safety and clean-up, often with fees; having the necessary equipment, such as tables, posters, slide projectors, and so forth, to develop the exhibit or presentation; having sign-up lists, permissions, or consents for research or recording; developing an event evaluation; developing a marketing strategy and guest invitation list; sending advertisements in a timely manner; responding to inquires about the event; developing materials such as a briefing book and agenda; making food arrangements; obtaining special resources such as continuing education unit certifications; inviting special guests; arranging for special equipment; and so forth. Sometimes, group members have served as event planners for other organizations or projects and will be familiar with some or all of these activities.

Special events require a team that reviews the requirements with an experienced academic/community planner, who will help to develop a task list, timeline, and assignment of responsibilities. A lead event organizer or co-organizers should be identified, and the legal requirements and funding resources should be reviewed with the Council, which must approve the event in advance based on a budget and work plan.

Implementation of the event typically requires the cooperation of many or all members of the working group and, most likely, members of other working groups in the project. This will likely mean that stipends for the project (in the past, we have agreed on $100 for a day of work) need to be arranged for the community participants who otherwise do not have their time covered for this work.

The style of the event should be consistent with good community standards and ethics, and be planned to be engaging and effective in the community. Dry academic lectures are to be avoided, for example, but that does not mean that information cannot be provided if the presentation is engaging, or there can be a mixture of information sessions and entertaining events on the same theme. Successful events can be enormously fun to plan for community and academic participants, and successful events in terms of community response can leave a lasting impression that energizes a working group or the project as a whole for many months.

Fig 5.7.

Share

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the board of directors of Healthy African American Families II; Charles Drew University School of Medicine and Science; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Reproductive Health; the Diabetes Working Groups; the Preterm Working Group; the University of California Los Angeles; the Voices of Building Bridges to Optimum Health; Witness 4 Wellness; and the World Kidney Day, Los Angeles Working Groups; and the staff of Healthy African American Families II and the RAND Corporation.

This work was supported by Award Number P30MH068639 and R01MH078853 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Award Number 200-2006-M-18434 from the Centers for Disease Control, Award Number 2U01HD044245 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Award Number P20MD000182 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Award Number P30AG021684 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control.