Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of Community-Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) and introduces the articles in this special issue. CPPR is a model to engage community and academic partners equally in an initiative to benefit the community while contributing to science. This article reviews the history of the partnership of community and academic institutions that developed under the leadership of Healthy African American Families. Central to the CPPR model is a framework of community engagement that includes and mobilizes the full range of community and academic stakeholders to work collaboratively. The three stages of CPPR (Vision, Valley and Victory) are reviewed, along with the organization and purpose of the guidebook presented as articles in this issue.

Keywords: Community-Partnered Participatory Research, Community Engagement, Community-Based Research, Action Research

Our Experience Working Together

The authors of this guidebook have worked together on partnered research and community action projects for more than 10 years, although our organizational histories predate our partnership.

Several of our authors are associated with Healthy African American Families (HAAF), an organization founded in 1992 with the goal of improving health outcomes in African American and Latino communities throughout Los Angeles County. Working with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and with numerous community and academic partners on a variety of projects, HAAF pioneered the concept of community-partnered research. HAAF evolved many of the guiding principles of community-academic collaboration that later formed the basis of the partnership described in this guidebook. Under the direction of Loretta Jones, the lead author of this guidebook and founder/executive director of HAAF, HAAF’s guidelines were developed to include community involvement in the project from beginning to end, practical use of the research findings within the community that created them, and communication of all findings to the community. For a number of years, before the authors of this guidebook began working together, HAAF had successfully applied its guiding principles to several key academic-community collaborations, including the Preterm Working Group (designed to improve pregnancy outcomes), the Diabetes Working Group (designed to engage the community in developing and implementing a pilot diabetes intervention), Building Bridges to Optimum Health (designed to improve health in minority neighborhoods), and Breathe Free (an asthma awareness and action initiative). For more information on HAAF initiatives, see Appendix 2.

Other guidebook authors are associated with Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science, the RAND Corporation, the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program, and the University of California at Los Angeles. (Table 1.1)

Table 1.1.

The Los Angeles Community Health Improvement Collaborative

| Community Partners | Academic and Clinical Partners | Pilot Programs |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy African American Families (HAAF) | Charles Drew University School of Medicine and Science | Community engagement in depression care for communities of color |

| Los Angeles Unified School District | RAND Health (a unit of the RAND Corporation) | Improving prevention and management of diabetes |

| QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership | University of California at Los Angeles | Community violence interventions for children through schools |

| Los Angeles County Department of Health Services | Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program | Promoting healthy births/reducing low-birth weight infants |

| Department of Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System | Centers: UCLA/Drew/RAND NIH Project Export Center | |

| Community Clinic Association of Los Angeles County | UCLA/DREW NIA Center for Health Improvement for Minority Elders UCLA/RAND/USC NIMH Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care UCLA Family Medicine Research Center |

More than 15 years ago, HAAF and community and academic partners, with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), started working together to develop an approach to engage the community in efforts to address health disparities through local ownership of problems and solutions. This work evolved into the development of a partnered-research infrastructure, the Los Angeles Community Health Improvement Collaborative (CHIC). The purpose of that Collaborative was to encourage shared strategies, partnerships and resources to support rigorous, community-engaged, health services research.

The Los Angeles Community Health Improvement Collaborative

The Collaborative sponsored new pilot efforts and partnerships, such as the Witness for Wellness initiative, and supported training programs such as the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program at UCLA and a “book club” on participatory research methods for community members and academics. That development stage led to the funding or renewal of several Centers with a major focus on addressing health and healthcare disparities through Community-Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR). The work of the Collaborative is continuing in the active life of these new Centers and in the pilot and main projects that they support. Pilot projects have grown into mature projects spanning community planning and action, and rigorous, partnered research initiatives. This guidebook draws on the lessons we have learned together in working on the collaborative, supplemented by the experience we gained through our prior work.

Our approach to CPPR uses a participatory research framework to blend evidence-based clinical or health services research with community-based knowledge and practice. At its core is an equal, mutually respectful partnership model that emphasizes community-academic collaboration at every step. Our goal is to build a sustainable partnership that will support numerous health research and action initiatives in Los Angeles over many years. We also seek to facilitate and support a set of focused networks operating on similar principles and procedures—networks that can support action-oriented, participatory research in a wide range of community-academic partnerships and initiatives.

Our work has focused on improving mental and physical health. However, we hope that our experience, guiding principles, mutually shared values, and processes will prove useful to community-academic partnerships in a wide variety of fields.

Our partnered research teams are unusual in that they include a number of academic clinicians. Clinicians, because of their background and training, may face a special set of challenges when undertaking a community-academic research partnership. Clinicians are often trained within a hierarchical authority structure, a style that may be further reinforced by the structure and incentives of academic medicine. Within such a structure, independence in science tends to be rewarded more highly than collaboration. The result can be a “top-down” approach to partnering that may conflict with the core values of power sharing that are central to CPPR. Further, clinical research places a particularly high value on randomized, controlled trials as the gold standard for validity, whereas CPPR tends to be based on mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative), logic models, and overall a more quasi-experimental, descriptive, or exploratory approach. Thus, our partnered research efforts have had to address issues of both professional style and scientific substance, to struggle with what partnership and scientific rigor means to academic and community policy leaders, while promoting equitable partnerships and rigorous research. As explained in more detail under “Guiding Principles for Community-Partnered Research” in Chapter 2, a CPPR partnership honors both community values and academic standards equally.

Facing these challenges openly and honestly has created strong partnership bonds and new opportunities for collaborations. We have consistently found high levels of creativity on the part of community members in responding to scientific challenges, and surprising partnership strengths across and within diverse community and academic participants. These strengths have allowed us to work within an infrastructure with an unusual breadth of community and academic partners across a wide diversity of partnered initiatives, including randomized trials, which to date have been rare in community-based participatory research in health. Further, sharing our work with policy leaders has opened new dialogues about the purposes of research and opportunities for new programs that more fully examine both how to conduct such research and what the findings may offer policymakers.

Our basic priorities and processes are rooted in a marriage between community values and academic goals. The guiding principles of this relationship are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Engaging the Community in CPPR: The Circle of Influence Model

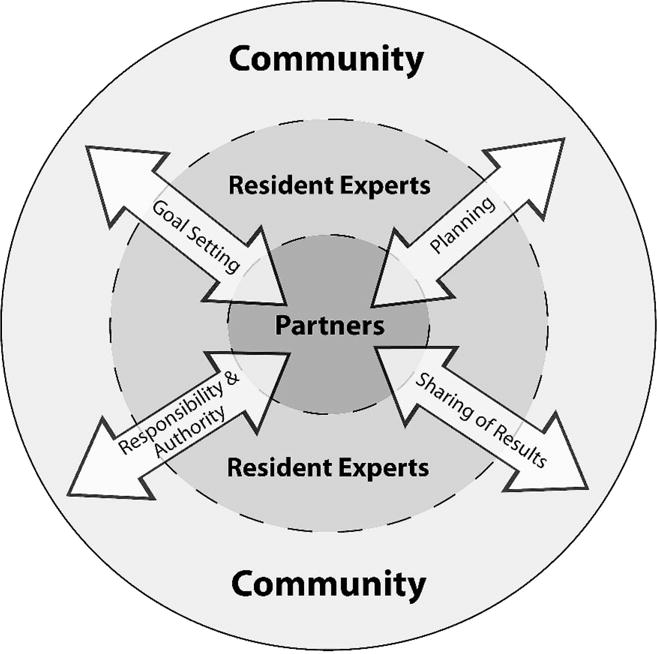

As an overview to CPPR, we offer the following graphic overview of the approach. (Figure 1.1) This process, originally presented by Loretta Jones at the Successful Models of Community-Based Participatory Research meeting hosted by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences on March 29–31, 2000, has proven useful in our CPPR collaboration.

Fig 1.1.

Circles of Influence Model. This model was developed by L. Jones, MA, D.S. Martins, MD, Y. Pardo, R. Baker and K. C. Norris, MD

The Circles of Influence Model illustrates the stakeholder structure of CPPR initiatives through a set of concentric circles: a core group of partners representing diverse stakeholders for a given issue; a set of resident experts (eg, community members, consultants) who move in and out of the initiative for given issues, advising and participating in work groups; and the community-at-large that both benefits from the initiative and provides input as the initiative unfolds. These stakeholders are engaged under the guiding principles of the partnership or collaboration in a set of specific functions or tasks: goal setting, planning, implementation with shared responsibility and authority, and results sharing or dissemination. The details on how this work is organized and completed are the subject of this guidebook.

Our “Illustration” Initiative: Witness for Wellness

Although HAAF and other partners have extensive previous experience with community-academic partnerships, for purposes of illustration (and, we hope, to make it easier for the reader to follow), most of the examples in this guidebook are drawn from our experience in working together on the Witness for Wellness (W4W) project.

The experience of working together on this key project has shaped our understanding and approach to all of our subsequent community engagement projects. Witness for Wellness is a health-related project (focusing specifically on the mental health issue of depression), but we believe that the lessons we learned in the course of this effort will apply to many types of community-academic partnered research projects.

Overcoming stigma was immediately identified as a key challenge. These early discussions led to a proposal to form a council of interested community agencies and members to plan over a 6-month period, an initiative concerning depression.

During the ensuing planning process, much was shared as different agency and community members, as well as academic partners, came to the planning table, including: different models of health and illness, stories of personal experience with depression or observations of clients suffering from depression, alternative views of what depression is, and many other fruitful discussions. A plan was formulated to share these community and academic perspectives with a modest community forum. More than 500 individuals attended a full-day session at the Los Angeles Science Museum.

A call for action led to a follow-up leadership planning conference with more than 75 interested individuals. This step was followed by the formation of three working groups: Talking Wellness (increasing depression awareness and reducing stigma), Building Wellness (educating health care workers to improve services outreach and quality), and Supporting Wellness (providing policy support and advocacy for vulnerable populations). Each group, along with all elements of the W4W initiative, developed its work through the three major stages of partnered research, Vision, Valley, and Victory, which are explained in more detail below. Although each of these steps had been developed and implemented in prior HAAF projects, the W4W program became a flagship initiative for integrating the approach with more traditional health services research approaches and for developing a language to share the model equally with community, academic partners, and friends. As W4W progressed, a similar form of the model was used in other initiatives involving HAAF and various community and academic partners. A listing of those initiatives to date, showing the history of the development of the model, is included in the appendix to this guidebook.

Stages of Partnered Research: Vision, Valley, Victory

In our model, partnered research initiatives unfold in three major stages, Vision, Valley, and Victory. The guidebook is organized with these stages in mind.

As we worked together, we realized that the three stages could be symbolized by holding up a hand. (Figure 1.2) The three gaps between our fingers make three Vs: Vision = developing strategies and goals for the project; Valley = carrying out the activities necessary to implement the project; and Victory = celebrating success, and completing and disseminating products.

Fig 1.2.

Vision, Valley, Victory

This shared symbol can help all project members identify with the project and remind us that everyone is working together to achieve Victory. During our work together, especially when we are encountering difficulties, team members remind each other of our goals simply by holding up a hand. Simple tools such as this hand signal are part of a partnership strategy promoting common understanding and power-sharing among partners with diverse backgrounds.

Vision

The Vision is a shared view of the project’s goals and strategy. The Vision must be compelling; it must sustain the team through and beyond the duration of the project. Developing a truly shared perspective for the Vision may often take 4 to 8 months, and is a distinctive piece of work. Community and academic partners may have very different views of issues, timing, strategy, participants, and desired outcomes. Negotiating these differences is key to arriving at an overall Vision that is compelling and a “win” to all concerned; the Vision must engage all partners in proceeding to the main work of the project. A clear and mutual understanding of the Vision is vital to every stage of the project, from doing the work to celebrating its completion and outcomes.

Valley

The Valley takes place when project tasks are done to realize the Vision. The word “Valley” emphasizes that a lot of hard work is required to climb the hill to success; knowing in advance that it will be hard work can help to stave off discouragement along the way. The work involves facing and overcoming many challenges, which can can include developing the partnerships needed for the task, developing strategies to address the issue, obtaining broader community feedback, piloting and evaluating the new strategies, and proceeding to a main implementation phase—depending on the type of issue and project. Accomplishing work of this scope usually requires breaking the project into manageable tasks, organizing working groups to accomplish the tasks, developing an action plan for each task, and evaluating the success of the work.

Victory

Victory is acknowledging and celebrating success, developing and disseminating products, and sharing the story with others, along with ensuring sustainability and related policy changes. A strength-based approach is vital at every stage of the project and small victory laps should be encouraged at many points along the way. Every successful meeting, every mutually agreed-on compromise, every completed action plan is one of a series of victories. But the Victory stage refers to a planned, distinct phase of work that completes the project while building capacity for the next partnered activity.

Within each stage – Vision, Valley, and Victory – partners work together following a plan-do-evaluate cycle. Each stage is planned and conducted, and joint evaluation of the outcome of the work at that stage informs the planning of the next. The plan-do-evaluate cycle is the main organizational structure in this guidebook for the subsections that describe the work involved within each of the three V stages.

Vision, Valley, and Victory are separate stages, but the work often overlaps. Vision, Valley, and Victory may be going on all at once in complex projects with multiple action plans being pursued by different working groups and subcommittees. Work from one stage can lead to changes in the framing of previous, as well as subsequent, stages. Insights gained in the Valley, for instance, may result in refinements to the Vision. Victories occur in every phase. And, the final Victory for one project may be the start of a new Vision for the next project.

Organization of this Guidebook

The remainder of this guidebook provides an overview of partnership principles and strategies that apply across all three major stages of partnered research (Vision, Valley, and Victory), reviews the work (plan-do-evaluate) of each stage, and provides a case history of W4W, the lead project for the Los Angeles Community Health Improvement Collaborative.

Chapter 2 provides an overview of partnership principles and strategies that define a CPPR approach and explains the “plan-do-evaluate” cycle which, supported by community engagement principles, structures the work flow within each stage.

Chapter 3 reviews the Vision stage and describes the plan-do-evaluate activities that apply to this stage.

Chapters 4, 5, and 6 describe the work of the Valley. Chapter 4 describes “Plan,” Chapter 5 describes “Do,” and Chapter 6 describes “Evaluate.” We have broken this discussion into three chapters only for convenience. In reality, team members must be aware of all phases of the Valley (and indeed of the overall project) at every stage.

Chapter 7 focuses on the Victory stage and discusses the plan-do-evaluate framework for this stage. Victory includes developing and sharing work products, celebrating the partnership’s work together, and positioning the partnership for broader impact and future work.

For us, the most important part of this guidebook is Appendix 1, where we ask you to share your experiences with us. (Figure 1.3) Community-academic research partnerships are new – and we all have much to learn. We hope that by sharing your experiences with us, we can learn together.

Fig 1.3.

Share

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the board of directors of Healthy African American Families II; Charles Drew University School of Medicine and Science; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Reproductive Health; the Preterm Working Group; the Diabetes Working Group; the University of California Los Angeles; the Voices of Building Bridges to Optimum Health; Witness 4 Wellness; and the World Kidney Day, Los Angeles Working Groups; and the staff of Healthy African American Families II and the RAND Corporation.

This work was supported by Award Number P30MH068639 and R01MH078853 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Award Number 200-2006-M-18434 from the Centers for Disease Control, Award Number 2U01HD044245 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Award Number P20MD000182 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Award Number P30AG021684 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control.