Summary

The effects of testosterone (T) and estradiol (E2) on cognition in men are confounded in extant studies. This randomized, placebo-controlled trial was undertaken to investigate the possible effects of E2 on cognition in older men. Twenty-five men with prostate cancer (mean age: 71.0 ± 8.8 years) who required combined androgen blockade treatment were enrolled. Performance on cognitive tests was evaluated at pre-treatment baseline and following 12 weeks of treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog and the nonsteroidal antiandrogen bicalutamide to determine whether specific cognitive functions would decline when the production of both T and E2 were suppressed. In the second phase of the study, either micronized E2 1 mg/day or an oral daily placebo was randomly added to the combined androgen blockade for an additional 12 weeks to determine whether E2 would enhance performance in specific cognitive domains (verbal memory, spatial ability, visuomotor abilities and working memory). Compared to pretreatment, no differences in scores occurred on any cognitive test following 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade. In the add-back phase of the study (Visit 3), the placebo-treated men, but not the E2-treated men, exhibited a trend towards improvement in their scores on both the immediate (p = .075) and delayed recall (p = .095) portions of a verbal memory task compared to baseline. Moreover, at Visit 3, placebo-treated men performed significantly better than the E2-treated men on both the immediate (p = .020) and delayed recall (p = .016) portions of the verbal memory task. Thus, combined androgen blockade plus add-back E2 failed to improve short- or long-term verbal memory performance in this sample of older men being treated for prostate cancer.

Keywords: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog, Estrogen, Cognition, Prostate cancer, Randomized controlled trial, Combined androgen blockade

In healthy males, decreases in total, free, and bioavailable testosterone levels occur with advancing age (Nankin and Calkins, 1986; Gray et al., 1991; Morley et al., 1997; Morley, 2000; Harman et al., 2001; Snyder, 2001; Vermeulen, 2001). Several large cross-sectional studies of changing hormone levels in elderly men have consistently found a 1–2% annual decline in free or bioavailable testosterone (Morley et al., 1997; Harman et al., 2001; Snyder, 2001; Vermeulen, 2001; Feldman et al., 2002), with the incidence of hypogonadism rising from 20% in 60–69-year-old men to 50% in those over 80 years of age (Harman et al., 2001). Moreover, since approximately 80% of circulating estradiol (E2), the most potent estrogen, is aromatized from testosterone (T) in men (Kaufman and Vermeulen, 2005), there is a corresponding decline in total and bioavailable E2 with increasing age (Ferrini and Barrett-Connor, 1998; Khosla et al., 1998; Van den Beld et al., 2000; Vermeulen et al., 2003).

Estrogen (E) and T mediate aspects of learning and memory in rodents (Bimonte and Denenberg, 1999; Gibbs, 2000; Dohanich, 2002; Gibbs, 2005) and in humans (see Sherwin, 2003; Sherwin and Henry, 2008 for reviews). Sex hormones modulate cognitive functioning either by binding to specific receptors in target regions of the brain or by activating second messenger systems (McEwen, 1976, 1981). T can act at these sites directly, or via its conversion to a more potent androgen, 5α-dihydrotestosterone (5α-DHT) by means of the 5α-reductase enzyme (McEwen, 1981) or it can act on E receptors in the brain through its conversion to E2 via the action of the aromatase enzyme (Naftolin and Ryan, 1975). The capacity of the sex steroid hormones to bind to specific receptors in target regions of the brain and to activate second messenger systems underlies their ability to influence cognitive functioning.

The small but consistent sex differences in performance in certain cognitive domains are characterized by males typically outperforming females on targeted, directed motor skills, quantitative tasks, and tasks of visuospatial abilities while females excel in verbal tasks, perceptual skills, and fine motor skills (Halpern, 1992). Indeed, the most well-established sex differences in cognitive functioning are that T enhances spatial abilities in men and E2 enhances verbal memory in women (Halpern, 1992).

Since androgens stimulate the growth of normal prostatic tissue as well as androgen-dependent prostatic tumors, pharmacological suppression of testicular function using gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRH-a) is a frequently used treatment for selected men with androgen-dependent prostate cancer (Canadian Pharmacists Association, 2007). Findings of studies that have evaluated cognition in men whose sex hormone levels decreased abruptly due to GnRH-a treatments for prostate cancer are mixed, with some reporting deleterious effects of testicular suppression on spatial, verbal, or executive abilities (Green et al., 2004; Bussiere et al., 2005; Jenkins et al., 2005; Cherrier et al., 2006, 2008), whereas others reported improvements in semantic memory or object recall (Salminen et al., 2003), or both (Cherrier et al., 2003; Salminen et al., 2004, 2005). Other investigations failed to find cognitive changes following GnRH-a treatment of prostate cancer patients compared to their own baseline scores (Edginton et al., 2004) or compared to healthy controls (Joly et al., 2006), or else reported improvements in cognition only after discontinuation of androgen suppression (Almeida et al., 2004). Still others failed to find significant changes in cognition following androgen suppression once the analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons (Green et al., 2002). Differences in sample characteristics, the composition of cognitive test batteries, and study designs are commonly cited to account for these disparities between studies.

Although there is substantial evidence that E2 maintains verbal memory when given to younger postmenopausal women (Sherwin and Henry, 2008), relatively little is known about the potential influence of E2 on aspects of cognitive functioning in men. In part, this is due to the failure to measure E2 in the majority of correlational studies of hormones and cognition in men (Sherwin, 2003; Thilers et al., 2006) or to the fact that both T and E2 levels increased significantly following exogenous T administration in replacement studies that evaluated the effects of sex steroid hormones on cognition in men (Cherrier et al., 2001, 2005; Maki et al., 2007), thereby making it difficult to disentangle the individual effects of these two sex steroid hormones. Only two studies evaluated the impact of E2 on cognitive functioning in older men with prostate cancer being treated with androgen blockade. Beer et al. (2006) found that verbal memory performance improved following treatment in 18 patients given 4 weeks of transdermal E2 as second line hormonal therapy for androgen independent prostate cancer. Taxel et al. (2004) failed to find an effect of 9 weeks of treatment with 17-β micronized E2 on verbal memory in a randomized controlled trial. However, the participants in the Taxel et al. (2004) study were a mixed sample of prostate cancer patients who were either on established GnRH-a therapy or were newly initiated on adjuvant GnRH-a therapy and were administered cognitive testing different numbers of times, which may have confounded their findings.

The purpose of the present study was to attempt to clarify the possible effect of E2 on cognition in older men scheduled to receive combined androgen blockade for androgen-dependent prostate cancer using a carefully controlled design. In this prospective, randomized controlled trial, a battery of neuropsychological tests was administered to men with prostate cancer before they were started on hormone treatment (Visit 1), again following 12 weeks of treatment with combined androgen blockade (Visit 2) and, for a third time, following an additional 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade with the concurrent and random addition of either add-back E2 or add-back placebo (Visit 3). Since the production of testicular hormones would remain suppressed during Phase 3, this experimental design allowed us to isolate the effects of E2 on cognition in older men. It was hypothesized that men with prostate cancer would experience a decrease in scores on tests of both spatial and verbal abilities following 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade with a GnRH-a and the nonsteroidal antiandrogen bicalutamide, and that scores on verbal memory would improve in the men who had randomly received add-back E2 but not in the men who had randomly received add-back placebo in addition to combined androgen blockade during Phase 3 of the study.

1. Methods

1.1. Participants

Men diagnosed with prostate cancer whose physician had recommended treatment with both a GnRH-a and a nonsteroidal antiandrogen were referred to the study by their urologist or radiation oncologist at the McGill University Health Center (MUHC), Montreal, Canada. Recruitment and subsequent follow-up started in September 2003 and ended in August 2006. Participants were screened by phone to ensure that they met inclusion and exclusion criteria. They were required to have at least 9 years of formal education, and be fluent in either English or French. Exclusion criteria (evaluated by self-report) were history of thrombotic disorders, stroke, transient ischemic attack, psychiatric illness, current use of psychotropic medications (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, stimulants, sedatives, and/or glucocorticoids), a history of head injury that resulted in loss of consciousness, or the suspected presence of mild cognitive impairment or any other neurological disorder.

1.2. Drugs

GnRH-a

The GnRH-a drug, chosen at the discretion of the treating physician, was either goserelin acetate 10.8 mg SC every 12 weeks (Zoladex, AstraZeneca, Loughborough, UK), leuprolide acetate 30 mg IM every 16 weeks (Lupron, Astra-Zeneca, Loughborough, UK), or leuprolide acetate for injectable suspension 22.5 mg SC every 12 weeks (Eligard, Atrix Laboratories Inc., Fort Collins, CO).

Nonsteroidal antiandrogen

Bicalutamide 50 mg/day (Casodex, AstraZeneca, Loughborough, UK) was administered to all men for 2 weeks prior to their treatment with GnRH-a to minimize the adverse effects of the transient elevation in serum T that occurs in the first 7–10 days following initiation of GnRH-a treatment (Belchetz et al., 1978). Bicalutimide is a nonsteroidal antiandrogen, devoid of other endocrine activity, that competitively inhibits the action of androgens by binding to cytosol androgen receptors in target tissue (Canadian Pharmacists Association, 2007). However, it has been established that bicalutamide is peripherally selective and has little effect on serum LH and T due to poor penetration across the blood–brain barrier (Furr, 1996).

Estradiol

17β micronized E2 1 mg/day (Estrace, Roberts Pharmaceutical Corporation, NJ).

Placebo

Oral placebo (Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, Canada).

1.3. Hormone assays

A blood sample was obtained from each participant at the beginning of each test session by a registered nurse. Samples were centrifuged immediately to separate the serum which was then stored at −50 °C until time of assay. At the conclusion of the study, sex hormone levels were assayed in the Endocrine Research Laboratory at the Hotel Dieu Hospital, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Montreal, Canada. T levels were assayed using the DSL Radioimmunoassay kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX). The intra-assay (within-run) coefficient of variation (C.V.) for this assay varied between 7.8% and 9.6% and the inter-assay C.V. varied between 8.4% and 9.1% for TT in the ranges from 2.4 to 68.4 nmol/L. This assay has a sensitivity of 0.28 nmol/L. E2 levels were assayed using the ADVIA Centaur Estradiol-6 assay kit (Bayer Corporation, USA). The intra-assay C.V. was 9.7% for E2 in the range from 36.8 to 461.6 pmol/L. The minimum sensitivity/detection limit of E2 was 36.7 pmol/L. The percentage of undetectable levels of E2 was 24% (Visit 1), 76% (Visit 2), and 53% (Visit 3). Plasma albumin levels were measured using the ADVIA 1650 Albumin assay kit (Bayer Corporation, USA). Plasma SHBG levels were measured using the DPC Immunoradiometric assay kit (Diagnostic Product Corporation, Los Angeles, CA). The intra-assay C.V. for this assay ranged from 2.8% to 5.3% and the inter-assay C.V. ranged from 7.9% to 8.5%. Sensitivity of this assay is 0.04 nmol/L. Bioavailable testosterone was calculated using the Södergård equation (Sodergard et al., 1982) using constants from Rosner (1997).

2. Neuropsychological test battery

2.1. Screening measures

Depression

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21-item self-report inventory designed to measure the extent and nature of depressive symptoms during the previous 2 weeks (Beck and Steer, 1993). Participants with a score of 13 or higher were excluded from the study.

General cognitive and mental status

The Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) assesses areas of global cognitive functioning including orientation, attention, calculation, recall and language (Folstein et al., 1975). It is also used as a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease (Folstein et al., 1975). Participants with a score of 23 or below were excluded from the study.

2.2. Spatial ability

Mental rotation

The adaptation (Vandenberg and Kuse, 1978) of the three-dimensional mental rotation test was used to measure the capacity for mental manipulation and rotation of geometric shapes. Participants were shown an image of a three-dimensional geometric object and asked to determine what the object would look like if it had been rotated in space. They were required to choose two correct responses from the four possibilities presented for each item.

Paper folding

The Paper Folding Test is a measure of mental manipulation (Ekstrom et al., 1976). Participants were presented with graphical representations of a piece of paper being folded several times before a hole was punched through it. They were then asked to imagine the placement of the holes if the paper was unfolded. For each item, participants were presented with five possibilities from which to choose a response.

Block design

The Block Design subtest of the WAIS-III (Wechsler, 1997) is a measure of visuoconstructive skill known to be sensitive to T levels. Participants were presented with a series of designs and were asked to reconstruct each image as quickly as they could with the blocks provided.

2.3. Verbal memory and verbal fluency

Verbal memory

The Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R) (Wechsler, 1987) measures verbal recall. Participants were read a story consisting of five sentences and were asked to recall the paragraph verbatim immediately following its presentation and, again, following a 45-min delay during which other tests were being administered.

Word-list learning

The Verbal Paired-Associates is a subtest of the WMS-R (Wechsler, 1987). Participants were read a list of 8 word pairs presented in random order four times. Immediately following each presentation and, again, following a 45-min delay, participants were cued with the first word in the pair and were asked to recall the accompanying paired word.

Verbal fluency

The Verbal Fluency Test (FAS) is a measure of word production (Benton and Hamsher, 1976). Participants were instructed to generate, in 60 s, as many words as possible that began with a particular letter of the alphabet, excluding variations of the same word, proper names and numbers.

2.4. Visuomotor scanning and attention

Digit symbol

The Digit Symbol subtest of the WAIS-III (Wechsler, 1997) is a measure of visuomotor scanning and attention. Participants were shown a row of numbers ranging from 1 to 9 at the top of a page, each of which had a symbol directly below it. They were then presented with a series of randomly devised numbers and were required to match each number with its corresponding symbol as quickly as possible in 2 min.

2.5. Working memory

Letter–number sequencing

The Letter–Number Sequencing task (Wechsler, 1997) involves the oral presentation of a string of numbers and letters. The participants are required to order them starting with the numbers in ascending order, followed by the letters in alphabetical order. The task is discontinued when a participant receives a score of zero on all three strings of letters and number in a given span size.

2.6. Procedure

Participants who met the inclusion criteria were scheduled for their first appointment between 9 and 11 AM to control for the circadian rhythm in T levels, although they are blunted in older men (Bremner et al., 1983). Upon their arrival at the Montreal General Hospital, MUHC, each patient read and signed a consent form that had been approved by the Institutional Review Board, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Canada. Then, a blood sample was obtained to measure baseline hormone levels, and the battery of neuropsychological tests was administered to establish baseline measures of cognitive function (Visit 1; week 0). Immediately following this pre-treatment test session, the first dose of the GnRH-a drug prescribed by their physician was administered.

After 12 weeks of treatment with the combined androgen blockade, participants returned to the hospital for their second visit where a second blood sample was drawn and the neuropsychological tests were repeated (Visit 2; week 12). Then, the men were randomly assigned to receive either E2 1 mg or placebo daily, at bedtime, for 12 weeks in addition to continuing treatment with GnRH-a plus bicalutamide. The final test session (Visit 3; week 24) occurred following 12 additional weeks of treatment with combined androgen blockade plus either add-back E2 or placebo; a blood sample was taken and the neuropsychological tests were administered for the third time. Information regarding possible side-effects of the drug treatments was solicited at each visit.

The add-back treatment phase of the study was double-blind. The hospital pharmacist devised the random assignment list and dispensed all drugs. A block randomization procedure was used to ensure equal numbers of participants in each group during the trial. The random assignment code was broken only following completion of the data collection. Then, both the patients and their physicians were informed which drug (E2 or placebo) the individual had received during the add-back phase of the study.

Participants were tested individually and were remunerated $15 per session for their transportation costs. Neuropsychological testing was conducted by trained assessors, and all the test results were scored independently by 2 assessors to increase the reliability of the data. Two comparable versions of each neuropsychological test were used to decrease practice effects and to increase reliability over multiple test times. Test order was randomized between subjects in either an A–B–A or in a B–A–B design.

A power analysis (Cohen, 1988) was performed in order to determine the sample sizes needed to find a large effect size. Results indicated that a sample of 26 subjects would be sufficient to detect a pre–post-treatment difference of 0.7 standard deviations between standardized means for a one-tailed test at an alpha level of .05 and a power of .80.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics

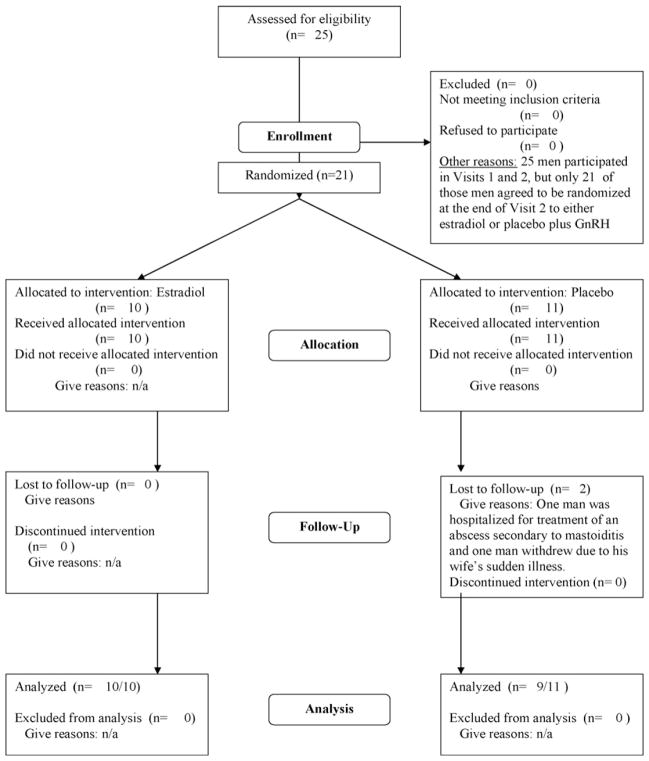

Twenty-five community-dwelling men with prostate cancer (mean age = 71.0 ± 8.8 years) met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A flow diagram of the participants’ trajectory through the study protocol is displayed in Fig. 1. Baseline characteristics for these participants appear in Table 1. At baseline, all men were well-educated and had intact cognitive function (as measured by the MMSE). Because of their rising PSA levels, their physicians had recommended treatment with combined androgen blockade. Six men had been diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer, 18 men had no signs of metastases, while the status of 1 man was unclear based on his bone scan. Twenty-one of the 25 men agreed to be randomized to either E2 (n = 10) or placebo (n = 11). At pretreatment baseline, there were no significant differences in age, years of education, MMSE scores, mood scores, anxiety scores, or severity of illness between men who had been randomly assigned to E2 and those randomly assigned to placebo (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the men’s trajectory through the study protocol. Please note that an intention-to-treat protocol was not carried out.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations (SD) of baseline demographic characteristics of the entire sample of men with prostate cancer (n = 25).

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.00 | 8.77 | 56–84 |

| Education (years) | 14.12 | 4.02 | 9–24 |

| Individual income (CDN dollars) | $37,500 | $15,490 | <$15,000 to >$60,000 |

| Household income (CDN dollars) | $43,950 | $14,200 | <$15,000 to >$60,000 |

| Mean | SD | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mini Mental State Examination | 28.80 | 1.21 | 26–30 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 6.20 | 4.60 | 0–12 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | 4.53 | 3.82 | 0–12 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 3.67 | 3.38 | 0–14 |

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations (SD) of baseline demographic and cancer characteristics between those who had been treated with either estradiol (n = 10) or placebo (n = 11).

| Group | Estradiol-treated men

|

Placebo-treated men

|

p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 71.60 | (9.90) | 72.64 | (7.92) | .793, ns |

| Education (years) | 14.30 | (3.06) | 14.00 | (5.00) | .872, ns |

| MMSE (score) | 29.17 | (0.98) | 28.63 | (1.41) | .437, ns |

| BDI (score) | 6.30 | (4.81) | 5.55 | (4.39) | .711, ns. |

| GDS (score) | 5.71 | (4.37) | 3.78 | (2.15) | .209, ns |

| BAI (score) | 2.97 | (2.65) | 4.18 | (3.89) | .419, ns |

| Tumor stage | 2.20 | (1.03) | 2.20 | (0.59) | .988, ns |

| Gleason score | 7.40 | (0.70) | 6.82 | (1.47) | .269, ns |

| PSA levels (ng/mL) | 19.51 | (13.23) | 15.96 | (15.66) | .583, ns |

MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory.

3.2. Hormone levels

At pre-treatment, mean levels of all sex steroid hormones of these older men fell within the low normal range for their age group (Table 3). After 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade, levels of all sex hormones decreased significantly compared to pretreatment values in all patients (p < .001). In the add-back phase of the study, only levels of E2 increased in the group receiving combined androgen blockade plus add-back E2 (p = .003), whereas the levels of all other sex hormones remained unchanged compared to values following the 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade-alone phase (Table 3).

Table 3.

Means (and standard deviations) of hormone levels of the entire sample of men with prostate cancer at pre-treatment (Visit 1), following 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade (Visit 2) and following treatment with either 12 weeks of estradiol (E2) or placebo (Pl) concurrent with combined androgen blockade (Visit 3).

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Normal rangea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total T (nmol/L) | 13.02 (6.22) | 2.31 (3.24)* | E2: 1.64 (0.32); Pl: 1.56 (0.13) | 9.0–25.0 |

| Free T (pmol/L) | 240.92 (127.61) | 37.64 (55.00)* | E2: 20.46 (9.82); Pl: 22.61 (3.53) | 182–670 |

| Bioavailable T (nmol/L) | 4.99 (2.62) | 0.83 (1.11)* | E2: 0.58 (0.23); Pl: 0.54 (0.09) | 3.7–13.8 |

| Total E2 (pmol/L) | 78.48 (50.73) | 40.11 (8.06)* | E2: 171.70 (123.73); Pl: 37.00 (0.00)** | <191 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42.68 (2.53) | 43.37 (2.11) | E2: 38.70 (12.77); Pl: 43.07 (1.50) | 37–48 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 44.52 (18.02) | 45.93 (13.17) | E2: 53.10 (21.47); Pl: 50.62 (12.44) | 12–52 |

T = Testosterone; Bio = Bioavailable; E2 = Estradiol; SHBG = Sex-Hormone Binding-Globulin.

Normal ranges for men aged >60 years.

Significant difference between Visit 1 and Visit 2 in whole sample of men (p < .001).

Significant difference at Visit 3 between estradiol-treated and placebo-treated men (p < .01).

3.3. Psychological and cognitive function

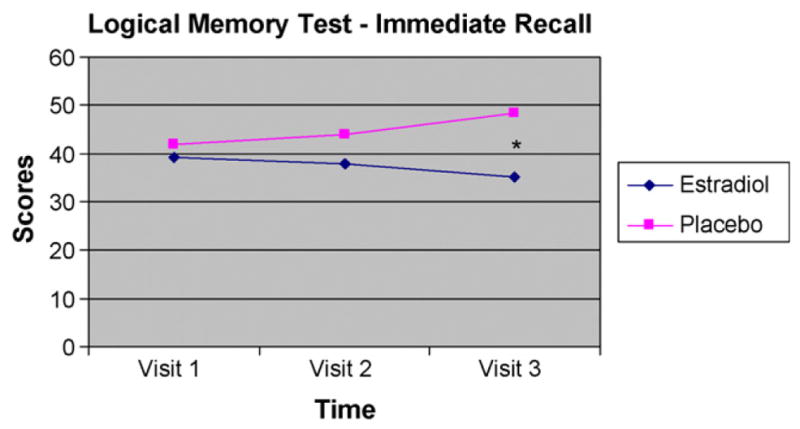

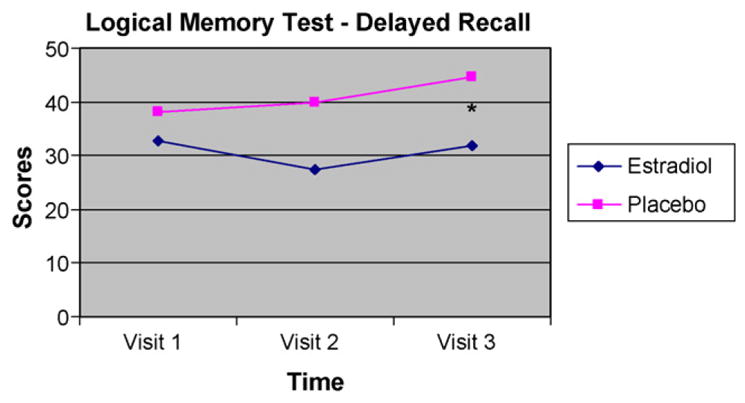

A series of 2 (Group) by 3 (Visit) repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed with treatment group as the between-subject factor (Group), time of testing as the within-subject factor (Time), and cognitive test scores as the dependent variables (Table 4). Age and years of education were included as covariates. Results revealed a significant main effect of Group on the delayed portion of the Logical Memory subtest scores which measures long-term verbal memory, F(1,19) = 5.95, p = .026. Planned comparisons (t-tests performed at each time point) revealed that placebo-treated men performed significantly better than E2-treated men on both the immediate [t(19) = −2.55, p = .020; 95% CI = −24.36 to −2.60] and delayed recall [t(19) = −2.65, p = .016; 95% CI = −23.19 to −2.74] portions of the Logical Memory task following the add-back phase (Visit 3), however there were no between-group differences in performance on either task at pretreatment baseline (Visit 1) or following 12 weeks of androgen blockade (Visit 2) (Figs. 2 and 3). While no differences in scores were evident between visits for the E2-treated men, the placebo-treated men exhibited a trend towards improvement on both the immediate [t(10) = −1.99, p = .075] and delayed recall [t(10) = −1.84, p = .095] portions of a verbal memory task between Visit 1 (baseline) and Visit 3. A trend was also evident between the two treatment groups such that placebo-treated men had better performance on the delayed recall portion of the Logical Memory task [t(19) = −1.77, p = .092] at Visit 2. No other significant main effects or interactions were evident for any of the other neuropsychological tests.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations (with post hoc power calculations) for the psychological and cognitive test measures of the entire sample of men with prostate cancer at pre-treatment (Visit 1), following 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade (Visit 2) and following treatment with either 12 weeks of estradiol (E2) or placebo (Pl) concurrent with combined androgen blockade (Visit 3).

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Post hoc powera | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck Depression Inventoryb | 6.20 (4.60) | 6.44 (4.63) | E2: 7.10 (5.02); Pl: 4.70 (3.71) | 3.68 |

| Geriatric Depression Scaleb | 4.53 (3.31) | 4.05 (4.69) | E2: 6.20 (4.24); Pl: 3.59 (3.48) | 2.65 |

| Mental Rotation Total Correctc | 3.45 (2.32) | 3.55 (2.15) | E2: 4.40 (2.72); Pl: 4.64 (2.72) | 1.86 |

| Paper Folding Total Correctc | 3.60 (1.63) | 3.48 (1.72) | E2: 5.10 (1.85); Pl: 4.51 (1.50) | 1.30 |

| Block Design Scaled Scorec | 12.76 (2.65) | 12.87 (2.35) | E2: 13.00 (2.36); Pl: 12.60 (3.14) | 2.12 |

| Digit Symbol Scaled Score | 10.88 (2.49) | 11.09 (2.34) | E2: 11.90 (3.21); Pl: 10.38 (3.05) | 1.99 |

| Letter–Number Sequencing Scaled Scorec | 12.20 (2.53) | 12.57 (2.43) | E2: 13.10 (2.96); Pl: 12.41 (1.74) | 2.02 |

| Logical Memory Immediate %c | 39.96 (11.38) | 39.38 (13.31) | E2: 35.17 (13.84); Pl: 48.55 (10.07)** | 9.10 |

| Logical Memory Delayed %c | 35.46 (13.41) | 33.22 (15.89) | E2: 31.75 (10.91); Pl: 44.71 (11.42)** | 10.73 |

| Verbal-Paired Associates Immediate Total Recall Scorec | 23.56 (7.06) | 22.66 (7.81) | E2: 22.60 (9.63); Pl: 25.27 (9.18) | 5.65 |

| Verbal-Paired Associates Delayed Total Recall Scorec | 8.60 (2.72) | 8.52 (2.94) | E2: 8.50 (2.46); Pl: 9.15 (2.64) | 2.18 |

| Verbal Fluency Total Scorec | 35.33 (12.15) | 36.77 (9.40) | E2: 35.40 (11.40); Pl: 37.05 (11.90) | 9.72 |

The minimum difference necessary to detect group differences on a given test with reasonable confidence given a one-tailed t-test, alpha = .05, a power of 0.8 and 20 degrees of freedom.

Lower scores indicate better performance.

Different versions of the test were used at the different test times.

Significant difference at Visit 3 between estradiol-treated and placebo-treated men (p < .05).

Figure 2.

Performance on the immediate recall portion of the Logical Memory test for estradiol-treated (n = 10) and placebo-treated (n = 11) men at pre-treatment (Visit 1), following 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade (Visit 2) and following treatment with either 12 weeks of estradiol (E2) or placebo (Pl) concurrent with combined androgen blockade (Visit 3). *Significant difference at Visit 3 between estradiol-treated and placebo-treated men (p < .05).

Figure 3.

Performance on the delayed recall portion of the Logical Memory test for estradiol-treated (n = 10) and placebo-treated (n = 11) men at pre-treatment (Visit 1), following 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade (Visit 2) and following treatment with either 12 weeks of estradiol (E2) or placebo (Pl) concurrent with combined androgen blockade (Visit 3). *Significant difference at Visit 3 between estradiol-treated and placebo-treated men (p < .05).

4. Discussion

The results of this prospective, randomized, controlled trial failed to support our first prediction that older men with prostate cancer would experience a decrease in scores on both spatial and verbal abilities following 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade treatment. Indeed, their cognitive scores remained stable following 12 weeks of combined androgen blockade treatment (Visit 2) compared to their pretreatment baseline scores despite significant decreases in their serum T and E2 levels between these two points in time. Although longitudinal studies of healthy older men whose sex hormone levels had decreased slowly over time with normal aging reported that lower levels of Tand E2 were associated with poorer performance in some aspects of their cognitive functioning (Muller et al., 2005; Thilers et al., 2006; Yonker et al., 2006), our results suggest that these hormone–behavior relationships may not generalize to older men with prostate cancer whose testicular function and adrenal androgen production were pharmacologically suppressed, resulting in a significant and much more abrupt decrease in testicular hormone secretion in 12 weeks or less. Indeed, results of the present study accord with those from a case-controlled study of 34 men with localized prostate cancer treated with a GnRH-a prior to radical prostatectomy that also failed to find changes in cognitive functions following 12 weeks of GnRH-a treatment (Edginton et al., 2004).

There are several possible explanations for why combined testicular and adrenal suppression failed to negatively influence cognition in our elderly participants. First, practice effects, that is, increases in scores on cognitive tests that occur when a person is retested using the same stimuli (Kaufman, 1994), normally occur with repeated neuropsychological testing because the stimuli and/or the strategy needed to perform the test presumably become more familiar to participants who are seeing them for a second or third time. The fact that practice effects failed to occur on any of the cognitive tests in either group of men from Visit 1 to Visit 2 suggests that the combined androgen blockade treatment may have reduced the ability of these men to learn from their earlier exposure to the material. However, the absence of a control group did not allow us to test this possibility.

Second, the participants were a mean age of 71 years and their sex hormone levels were in the low-normal range at pre-treatment; indeed, nearly one-third of the men in the sample were hypogonadal based on their morning levels of bioavailable T which were below 3.8 nmol/L (Morales and Lunenfeld, 2002). Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the men’s scores on the cognitive tests may already have been depressed at pre-treatment (Visit 1) due to their low T and E2 levels which would have caused a floor effect. Alternatively, the modest size of the absolute decrease in hormone levels from baseline to 12 weeks post-treatment with combined androgen blockade in these older men may have been insufficient to influence their cognitive function.

Third, it is possible that the 12-week duration of gonadal suppression in this study may have been too short to induce changes in cognitive function. Indeed, most studies that have reported changes in cognitive function following androgen deprivation treatment have utilized longer durations of testicular suppression since most evaluated cognition at least 6–12 months after baseline measures had been obtained (Green et al., 2002, 2004; Cherrier et al., 2003; Salminen et al., 2003, 2004, 2005). In one study, significant changes in aspects of cognition were only found following 12 months, but not following 6 months, after the commencement of androgen deprivation (Salminen et al., 2004), suggesting that a treatment duration of greater than 12 weeks might have been necessary to observe cognitive changes in our sample. Additionally, it is possible that our statistical methods decreased our ability to detect significant results, should they exist. For example, while Jenkins et al. (2005) found no differences in cognition following 3–5 months of androgen deprivation therapy in men with localized prostate cancer using repeated-measures ANOVAs, they found significant decreases in cognitive test performance when the same data were analyzed using a measure of Reliable Change Index, a technique used to assess changes in individual performance across sample times that might be masked by group data. Indeed, it is possible that statistical analyses that use the mean or average over time, such as those used in our study, may be more likely to result in null findings since individual variation may be obscured by group data (Cherrier et al., 2008).

Given the conflicting results in the existing literature on cognition in men whose sex hormone levels have decreased abruptly due to the pharmacological intervention for prostate cancer, it is difficult to resolve the differences in findings between our work and those of others, although differences in sample characteristics, cognitive test batteries, and study designs have commonly been cited to account for these disparities. For example, there may be expected differences between studies that used monotherapies (GnRH-a alone) and those that used GnRH-a concomitantly administered with bicalutamide (combined androgen blockade) which causes a more severe androgen depleted state. Likewise, studies that used intermittent as opposed to continuous androgen blockade may not be comparable. Finally, it is difficult to compare findings from repeated-measures designs to those from cross-sectional designs in which pretreatment scores are unavailable and the duration of androgen suppression is variable.

The results of this study also failed to support the second hypothesis that add-back E2 would improve performance on tests of verbal memory in older men being treated with combined androgen blockade. No significant changes in scores on both the short- and long-term verbal memory tests occurred following 12 weeks of treatment with combined androgen blockade in combination with either add-back E2 or add-back placebo compared to scores following androgen blockade alone (Visit 2). However, the combined androgen blockade plus placebo group performed significantly better than the combined androgen blockade plus E2 group on both the immediate and delayed recall portions of the Logical Memory task at Visit 3. This may have occurred because the combined androgen blockade plus placebo group may have benefited more from their previous exposure to the test material than the add-back E2 group. If this is true, it would suggest that the men in the add-back placebo group had benefited from practice effects due to earlier administrations of the verbal memory tests whereas the E2-treated men did not. This raises the possibility that the addition of E2 to combined androgen blockade in these older men with prostate cancer may have actually impaired their memory. These findings are consistent with those of Taxel et al. (2004) who also failed to find an effect on verbal memory in older men with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy and add-back E2. Although verbal memory scores improved in 18 patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer receiving 4 weeks of second line hormonal therapy with transdermal E2 (a treatment which leads to anorchid testosterone concentrations) (Beer et al., 2006), it is difficult to compare these findings to those in the present study because the patient characteristics and hormone manipulations differed markedly.

One possible explanation for the failure of E2 to influence verbal memory in the older men in this study being treated with combined androgen blockade therapy is based on the evidence that the brain responds differently to sex steroid hormones in older age because neurons and/or E2 receptors may become less sensitive or less responsive to E2 following a prolonged period of E deprivation (Jezierski and Sohrabji, 2001). There is also evidence that the estrogenic enhancement of dendritic sprouting that occurs in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in young and middle-aged ovariectomized (OVX) rodents fails to occur in OVX aged animals given E2 (Adams et al., 2001). Furthermore, whereas E2 increased the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the olfactory bulb in young OVX rats, it actually decreased the expression of this brain growth factor in aged OVX female animals following treatment with E2 (Jezierski and Sohrabji, 2001), suggesting that the administration of E2 to older animals may cause harm. These findings gave rise to the critical period hypothesis of estrogen effects on the brain which holds that estrogen therapy confers optimal cognitive benefits when initiated closely in time to the menopausal transition, but that the initiation of treatment in women over the age of 65 years will not be neuroprotective and may even cause harm (Resnick and Henderson, 2002: Gibbs and Gabor, 2003). If these age-related differences in estrogen and brain structure and function also occur in older males, they might explain the failure of the E2-treated men to benefit from a practice effect on tests of verbal memory in the present study. Although it seems reasonable to think that older male brains would react similarly to E2 as do older female brains, at the present time, there are no findings from basic neuroscience to support this contention.

One additional caveat regarding the present findings and their interpretation is that, at Visit 2, the placebo-treated men showed a trend towards better performance on the delayed recall portion of the Logical Memory task prior to randomization to either E2 or placebo. Therefore, the significant between-group findings on this measure at Visit 3 need to be interpreted cautiously. However, the fact that there were no differences between the groups on important demographic characteristics (e.g., age, education, global cognitive functioning, depression, anxiety or tumor stage) prior to randomization suggests that the Visit 3 results is likely valid.

Finally, it is important to note that the participants in this study were administered bicalutimide for 2 weeks prior to the initiation of GnRH-a treatment in accordance with the standard treatment protocol at the university hospital from which we recruited these patients, and its goal was to minimize the adverse effects of the transient elevation in serum T that occurs in the first 7–10 days following initiation of GnRH-a treatment (Belchetz et al., 1978). Because it would have been unethical to delay the medical treatment of these patients at the time of their referral, baseline cognitive levels could be evaluated only after the commencement of bicalutimide just prior to the patient’s referral to the study. Therefore, to standardize the collection of our baseline data and to spare the participants extra travel and effort, the first test session was scheduled to occur immediately prior to their appointments for the administration of their initial dose of GNRH-a. Given that bicalutimide has been shown to bind selectively to human prostate androgen receptors without stimulating the HPA axis (Furr, 1996), it is unlikely that bicalutimide affected cognitive functioning.

Two patients who had been randomized to the placebo group withdrew from the study during its progress; one man was hospitalized for treatment of an abscess secondary to mastoiditis and a second patient withdrew due to his wife’s sudden illness. Two men reported mild breast sensitivity while receiving E2 treatment but neither withdrew from the study. No other drug side-effects were reported. Therefore, the oral administration of E2 1 mg/day did not cause any serious side-effects in the men who received it for 12 weeks.

The strengths of this study are that the men who were randomized to the two add-back groups did not differ on important variables that could have independently influenced cognitive functioning such as age, level of education, and degree of illness severity. Moreover, all men were euthymic and had anxiety scores in the normal range. Neither were there between-group differences in hormonally related symptoms such as hot flushes, and sleep disturbances as measured by the Extended Prostate Cancer Index (not reported here). This increases the confidence that the cognitive findings can be attributed to the hormonal treatment itself. A limitation of this study is that the sample size was small and the majority of men who participated were Caucasian, well-educated, and of high-average socioeconomic status, the same characteristics that are thought to protect against cognitive decline with aging. This underscores the importance of evaluating cognitive functioning in men of other ethnicities and other socioeconomic backgrounds. Because considerable numbers of men with prostate cancer are currently being treated with GnRH-a drugs long-term, future research in this area should focus on clarifying the impact of these drugs on cognitive functioning in larger number of men of various races, educational and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Armen Aprikian, Luis Souhami, Marie Duclos, Marc David, Sergio Faria, and George Shenouda for their patient referrals to this study and Rhonda Amsel, M.Sc., for statistical consultation. We also would like to thank the men who gave of their time and effort to participate in this study.

Role of funding source

This study was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (No. MOP-77773) awarded to Dr. Barbara B. Sherwin and by Research Studentships awarded to Dr. Rose H. Matousek by the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) and by the Psychosocial Oncology Research Training (PORT) Program, McGill University. These funding agencies had no further role in study design, in the collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen. 2009.06.012.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Adams MR, Shah RA, Janssen WGM, Morrison JH. Different modes of hippocampal plasticity in response to estrogen in young and aged female rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8071–8076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141215898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida OP, Waterreus A, Spry N, Flicker L, Martins RN. One year follow-up study of the association between chemical castration, sex hormones, beta-amyloid, memory and depression in men. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1993. Patent No. [Google Scholar]

- Beer TM, Bland LB, Bussiere JR, Neiss MB, Wersinger EM, Garzotto M, Ryan CW, Janowsky JS. Testosterone loss and estradiol administration modify memory in men. J Urol. 2006;175:130–135. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belchetz PE, Plant TM, Nakai Y, Keogh EJ, Knobil E. Hypophyseal responses to continuous and intermittent delivery of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Science. 1978;202:631–633. doi: 10.1126/science.100883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination Iowa. University of Iowa Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bimonte HA, Denenberg VH. Estradiol facilitates performance as working memory load increases. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner WJ, Vitiello MV, Prinz PN. Loss of circadian rhythmicity in blood testosterone levels with aging in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56:1278–1281. doi: 10.1210/jcem-56-6-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussiere JR, Beer TM, Neiss MB, Janowsky JS. Androgen deprivation impairs memory in older men. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:1429–1437. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.6.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Pharmacists Association. Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (CPS): The Canadian reference for health professionals. Webcom Limited; Toronto: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier MM, Asthana S, Plymate S, Baker L, Matsumoto AM, Peskind E, Raskind MA, Brodkin K, Bremner W, Petrova A, LaTendresse S, Craft S. Testosterone supplementation improves spatial and verbal memory in healthy older men. Neurology. 2001;57:80–88. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier MM, Rose AL, Higano C. The effects of combined androgen blockade on cognitive function during the first cycle of intermittent androgen suppression in patients with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;170:1808–1811. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091640.59812.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier MM, Matsumoto AM, Amory JK, Ahmed S, Bremner W, Peskind ER, Raskind MA, Johnson M, Craft S. The role of aromatization in testosterone supplementation–effects on cognition in older men. Neurology. 2005;64:290–296. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149639.25136.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier MM, Montgomery R, Nelson PS, Yu EY, Higano CS. Prospective measurements of mood and cognition in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy for biochemical relapse of prostate cancer. Poster presented at the 2006 Prostate Cancer Symposium.2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier MM, Aubin S, Higano CS. Cognitive and mood changes in men undergoing intermittent combined androgen blockade for non-metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;18:237–247. doi: 10.1002/pon.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power for the Behavioral Sciences. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dohanich GP. Gonadal steroids, learning and memory. In: Pfaff DW, Arnold AP, Etgen AM, Fahrbach SE, Rubin RT, editors. Hormones, Brain and Behavior. Academic Press; San Diego: 2002. pp. 265–327. [Google Scholar]

- Edginton TL, Jenkins V, Shilling V, Bloomfield DJ. An investigative longitudinal pilot study of the cognitive effects of reversible hormone therapy for prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:S21–S22. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom RB, French JW, Harman HH, Derman D. Kit of Factor-referenced Cognitive Tests. Educational Testing Service; Princeton: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HA, Longcope C, Derby CA, Johannes CB, Araujo AB, Coviello AD, Bremner WJ, McKinlay JB. Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:589–598. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrini RL, Barrett-Connor E. Sex hormones and age: a cross-sectional study of testosterone and estradiol and their bioavailable fractions in community-dwelling men. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:750–754. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr BJA. The development of Casodex (bicalutamide): preclinical studies. Eur Urol. 1996;29:83–95. doi: 10.1159/000473846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB. Long-term treatment with estrogen and progesterone enhances acquisition of a spatial memory task by ovariectomized aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB. Testosterone and estradiol produce different effects on cognitive performance in male rats. Horm Behav. 2005;48:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB, Gabor R. Estrogen and cognition: applying pre-clinical findings to clinical perspectives. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:637–643. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray A, Feldman HA, McKinlay JB, Longcope C. Age, disease, and changing sex hormone levels in middle-aged men: results of the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73:1016–1025. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-5-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green HJ, Pakenham KI, Headley BC, Yaxley J, Nicol DL, Mactaggart PN, Swanson C, Watson RB, Gardiner RA. Altered cognitive function in men treated for prostate cancer with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogues and cyproterone acetate: a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int. 2002;90:427–432. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green HJ, Pakenham KI, Headley BC, Yaxley J, Nicol DL, Mactaggart PN, Swanson CE, Watson RB, Gardiner RA. Quality of life compared during pharmacological treatments and clinical monitoring for non-localized prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int. 2004;93:975–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern DF. Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:724–731. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V, Bloomfield D, Shilling V. Does neoadjuvant hormone therapy for early prostate cancer affect cognition? Results from a pilot study – reply. BJU Int. 2005;96:48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezierski MK, Sohrabji F. Neurotrophin expression in the reproductively senescent forebrain is refractory to estrogen stimulation. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly F, Alibhai SMH, Galica J, Park A, Yi QL, Wagner L, Tannock IF. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy on physical and cognitive function, as well as quality of life of patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer. J Urol. 2006;176:2443–2447. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS. Practice effects. In: Sternberg RJ, editor. Encyclopedia of Human Intelligence. Macmillan Publishing Company; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Vermeulen A. The decline of androgen levels in elderly men and its clinical and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:833–876. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla S, Melton LJ, III, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Klee GG, Riggs BL. Relationship of serum sex steroid levels and bone turnover markers with bone mineral density in men and women: a key role for bioavailable estrogen. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;82:2266–2274. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki PM, Ernst M, London ED, Mordecai KL, Perschler P, Durso SC, Brandt J, Dobs A, Resnick SM. Intramuscular testosterone treatment in elderly men: evidence of memory decline and altered brain function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4107–4114. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Interactions between hormones and nerve-tissue. Sci Am. 1976;235:48–58. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0776-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Neural gonadal–steroid actions. Science. 1981;211:1303–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.6259728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales A, Lunenfeld B. International Society for the Study of the Aging Male. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males Official recommendations of ISSAM. Aging Male. 2002;5:74–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE. Testosterone. Human Press; Totowa: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE, Kaiser FE, Perry HM., III Longitudinal changes in testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone in healthy older men. Metabolism. 1997;46:410–413. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Aleman A, Grobbee DE, de Haan EHF, van der Schouw YT. Endogenous sex hormone levels and cognitive function in aging men – is there an optimal level? Neurology. 2005;64:866–871. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000153072.54068.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naftolin F, Ryan KJ. The metabolism of androgen in central neuroendocrine tissues. J Steroid Biochem. 1975;6:993–997. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(75)90340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nankin HR, Calkins JH. Decreased bioavailable testosterone in aging normal and impotent men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63:1418–1420. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-6-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Henderson VW. Hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer disease: a critical time. JAMA. 2002;288:2170–2172. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner W. Errors in measurement of plasma free testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2014–2015. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.6.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen E, Portin R, Korpela J, Backman H, Parvinen LM, Helenius H, Nurmi M. Androgen deprivation and cognition in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:971–976. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen EK, Portin RI, Koskinen A, Helenius H, Nurmi M. Associations between serum testosterone fall and cognitive function in prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7575–7582. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen EK, Portin RI, Koskinen AI, Helenius HYM, Nurmi MY. Estradiol and cognition during androgen deprivation in men with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1381–1387. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin BB. Steroid hormones and cognitive functioning in aging men. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;20:385–393. doi: 10.1385/JMN:20:3:385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin BB, Henry JF. Brain aging modulates the neuroprotective effects of estrogen on selective aspects of cognition in women: a critical review. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:88–113. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PJ. Effects of age on testicular function and consequences of testosterone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2369–2372. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodergard R, Backstrom T, Shanbhag V, Carstensen H. Calculation of free and bound fractions of testosterone and estradiol-17β to human plasma proteins at body temperature. J Steroid Biochem. 1982;16:801–810. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(82)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxel P, Stevens MC, Trahiotis M, Zimmerman J, Kaplan RF. The effect of short-term estradiol therapy on cognitive function in older men receiving hormonal suppression therapy for prostate cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:269–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilers PP, MacDonald SWS, Herlitz A. The association between endogenous free testosterone and cognitive performance: a population-based study in 35 to 90 year-old men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Beld AW, de Jong FH, Grobbee DE, Pols HAP, Lamberts SWJ. Measures of bioavailable serum testosterone and estradiol and their relationships with muscle strength, bone density, and body composition in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3276–3282. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg SG, Kuse AR. Mental rotations, a group test of three-dimensional spatial visualization. Percept Mot Skills. 1978;47:599–604. doi: 10.2466/pms.1978.47.2.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A. Androgen replacement therapy in the aging male: a critical evaluation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2380–2390. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A, Kaufman JM, Goemaere S, Van Pottelberg I. Estradiol in elderly men. Aging Male. 2003;5:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler DA. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler DA. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Manual. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Yonker JE, Eriksson E, Nilsson LG, Herlitz A. Negative association of testosterone on spatial visualization in 35 to 80 year old men. Cortex. 2006;42:376–386. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.