Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The importance of home research study visit capacity in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) studies is unknown.

METHODS

All evaluations are from the prospective Adult Changes in Thought study. Based on analyses of factors associated with volunteering for a new in-clinic initiative, we analyzed AD risk factors and the relevance of neuropathological findings for dementia comparing all data including home visits, and in-clinic data only. We performed bootstrapping to determine whether differences were greater than expected by chance.

RESULTS

Of the 1,781 people enrolled 1994–1996 with ≥1 follow-up, 1,369 (77%) had in-clinic data, covering 61% of follow-up time. In-clinic data resulted in excluding 76% of incident dementia and AD cases. AD risk factors and the relevance of neuropathological findings for dementia were both different with in-clinic data.

DISCUSSION

Limiting data collection in AD studies to research clinics alone likely reduces power and also can lead to erroneous inferences.

Keywords: Home research study visits, research clinic study visits, missing data, bias, prospective studies, cohort studies, longitudinal studies, inference, dementia, neuropathology

1. Introduction1

Many studies do not include capacity for home study visits. Home visits add staff travel time, expense, and complexity to study administration. Despite these burdens there is a modest literature encouraging home visit capacity for studies of older people [1–5]. These papers emphasize benefits of increasing underrepresented ethnic diversity [2] or larger samples [6]. One paper suggests home visit capacity may improve generalizability [1]. To our knowledge, the relevance of home visit capacity for validity of findings in dementia studies has not been addressed.

We recently invited a active study participants who had agreed to brain autopsy and were thus especially prone to volunteer to consider a new initiative that included data collection in a research clinic – but not at home – and an MRI scan. Our study participants are particularly interested in research [7]. We analyzed factors associated with volunteering. As we will show, whether the previous study visit was at home or at the research clinic was the most important factor associated with volunteering. These findings led us to consider the importance of home study visit capacity. We analyzed data from the the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study original cohort, for whom we have 20 years of follow-up. We considered the data we would observe if we lacked home visit capacity. We focused on risk factors for AD and associations between autopsy neuropathological findings and dementia during life.

2. Methods

2.1. Parent study description, ethical considerations, and funding

Detailed methods for ACT have been published [8–10]. The original cohort enrolled 1994–1996 included 2,581 randomly selected dementia-free people age ≥65 who were members of Group Health, a Washington State health care system. An additional 811 participants were enrolled 2000–2003, and in 2005 we began continuous enrollment. Participants are evaluated at 2-year intervals at a research clinic or in their home at the participant’s choice to identify incident dementia cases. Other than location (i.e., home vs. clinic), study visits are identical.

All active participants with autopsy consent – regardless of enrollment cohort – were eligible to be invited to consider a new initiative, as detailed below. Subsequent risk factor and neuropathological analyses reported here are from the original cohort enrolled 1994–1996.

Study procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards of Group Health and the University of Washington. Participants provided written informed consent.

ACT is supported by the National Institute on Aging, which had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

2.2. Dementia identification

Participants were assessed at home or in clinic for dementia every 2 years with the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI), for which scores range from 0 to 100 and higher scores indicate better cognitive functioning[11]. Participants with scores of 85 or less underwent further evaluations, including a clinical examination and a battery of neuropsychological tests; dementia evaluations are in the participant’s home regardless of the location of the triggering visit. Results of these evaluations, laboratory testing, and imaging records were reviewed in a consensus conference, where research criteria were used to identify cases of dementia [12] and probable or possible AD [13]. Dementia-free participants continued with scheduled follow-up visits.

2.3. Autopsy consent

Information about postmortem brain examination procedures is made available at study visits; participants are invited to provide consent for brain autopsy. Between 25–30% of ACT participants have consented to autopsy.

2.4. Section 1: Factors associated with volunteering for an ancillary study that involved an in-clinic visit and MRI

We asked 145 active ACT participants with current autopsy consent to consider a new initiative that included in-clinic data collection and an MRI. We analyzed associations between volunteering and a variety of factors as listed in Table 1. Medical comorbidity was estimated using RxRisk [14] and Charlson [14] scores. We used Fisher’s exact test, t-tests, or Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests, as appropriate. All variables with a univariate p<0.20 were candidates for a multivariate logistic regression model where volunteer status was the dependent variable. We controlled multivariate models for age and sex.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 145 ACT participants with active autopsy consents who volunteered for an additional study involving in-clinic data collection and an MRI and those who did not volunteer (Section 1)

| People who volunteered (n=59) |

People who did not volunteer (n=84) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N or mean | % or SD | N or mean | % or SD | p value |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Male sex | 26 | 43% | 24 | 29% | 0.11 |

| Mean age | 79.5 | 6.2 | 82.4 | 7.6 | 0.016 |

| Education | 0.09 | ||||

| ≤12 years | 25 | 41% | 47 | 56% | |

| ≥13 years | 36 | 59% | 37 | 44% | |

| Income and employment | |||||

| Income* | 0.024 | ||||

| <$30,000 | 8 | 14% | 23 | 31% | |

| ≥$30,000 | 51 | 86% | 52 | 69% | |

| Employment status | 0.19 | ||||

| Employed or homemaker | 10 | 16% | 7 | 8% | |

| Retired | 51 | 84% | 77 | 92% | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Comorbidity indices | |||||

| Mean RxRisk score | 2695 | 810 | 2769 | 1120 | 0.97 |

| Mean Charlson index | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 0.18 |

| Activities of daily living (ADLs) | |||||

| Mean sum score | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.18 |

| Any ADL† | 14 | 23% | 30 | 36% | 0.11 |

| Instrumental ADLs (IADLs) | |||||

| Mean IADL sum score | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.20 |

| Any IADL | 8 | 13% | 22 | 26% | 0.06 |

| Shopping‡ | 3 | 5% | 16 | 19% | 0.013 |

| Number of medications | 2.9 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 0.10 |

| ACT study characteristics | |||||

| Number of visits | 4.8 | 2.6 | 5.1 | 3.0 | 0.61 |

| CASI score | 95.6 | 3.2 | 94.8 | 3.9 | 0.10 |

| Home research study visit | 17 | 28% | 47 | 56% | 0.001 |

| Study cohort | 0.34 | ||||

| Original (1994–1996) | 7 | 11% | 16 | 19% | |

| Expansion (2000–2003) | 13 | 21% | 21 | 25% | |

| Continuous (2005–) | 41 | 67% | 47 | 56% | |

Income was missing for 2 people who volunteered (3%) and 9 people who did not volunteer (11%).

There were no statistically significant differences in proportion of people who endorsed specific ADLs including bathing, bed mobility, dressing, feeding, toileting, or walking

There were no statistically significant differences in proportions of people who endorsed specific IADLs other than shopping (including paying bills, doing housework, preparing meals, or using the phone).

2.5. Section 2: Importance of home visits for analyses of AD risk factors

We constructed two data sets from the original cohort: one with all data (the “all data” dataset), and the second excluding home visit data (the “clinic only” dataset). We modeled probable or possible AD [15]. We used Cox models with age as the time axis [16] and included age at baseline as a covariate. We evaluated the factors shown in Table 2. We compared hazard ratios from the “all data” and “clinic only” datasets using a bootstrapping procedure. The “clinic only” data are a subset of the “all data” dataset, so different findings could be due to the smaller sample. We therefore drew (with replacement) random subsets of the “all data” dataset that were the same size as the “clinic only” dataset. Each randomly drawn dataset has the same size as the “clinic only” dataset, so different sample sizes do not drive results. In each drawn dataset, we performed the same risk factor analyses. We determined the proportion of drawn datasets with hazard ratios more extreme than those of the “clinic only” dataset. The bootstrap p values indicate the proportion of drawn datasets with more extreme findings than the “clinic only” dataset, which help us understand whether “clinic only” and “all data” hazard ratios differ more than expected by chance alone.

Table 2.

Section 2: Factors associated with risk for possible or probable AD considering all data (left columns) and considering only data collected at research clinic study visits (right columns), along with bootstrap results (far right column)*

| All data | Clinic-only data | Bootstrap results |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | p value | Hazard ratio | p value | p value | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |

| Female | 1.07 | 0.52 | 1.16 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Age | 1.12 | <0.001 | 1.14 | <0.001 | 0.040 |

| Education | Omnibus: p<0.001 | Omnibus: p=0.32 | |||

| ≤12 years | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |

| 13–16 years | 0.79 | 0.015 | 0.84 | 0.38 | 0.61 |

| 17+ years | 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.15 | 0.44 |

| Race | |||||

| Other | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |

| White | 0.83 | 0.26 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.35 |

| Medical conditions | |||||

| Diabetes | 1.16 | 0.40 | 1.76 | 0.09 | 0.039 |

| Hypertension | 0.85 | 0.13 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 0.62 |

| Heart | 1.03 | 0.81 | 1.36 | 0.24 | 0.09 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.29 | 0.13 | 2.42 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| APOE genotype | |||||

| 0 ε4 alleles | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |

| 1 or more ε4 alleles | 1.66 | <0.001 | 2.28 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Comorbidity | Omnibus: p=0.39 | Omnibus: p=0.55 | |||

| RxRisk = 1 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |

| RxRisk = 2 | 0.92 | 0.54 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.66 |

| RxRisk = 3 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.20 | 0.034 |

| RxRisk = 4 | 1.18 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 0.044 |

Bootstrap results give the probability that hazard ratios this different would be observed by chance alone. Each bootstrap sample is generated by randomly drawing individuals from the “all data” dataset with replacement until the same sample size as the “clinic only” dataset is reached. We then ran the same Cox model with that sample and kept track of its hazard ratio. We repeated this procedure 10,000 times, and ranked the hazard ratios. We compared the observed hazard ratio for the “clinic only” dataset to the bootstrapped hazard ratios to obtain the bootstrapped p values.

2.6. Section 3: Importance of home visits for analyses neuropathological findings and dementia

We considered the 347 members of the original cohort who died and came to autopsy as of November 2014. We required the most recent study visit to be within two years of death for people who died without a diagnosis of dementia to minimize dementia misclassification. Again we constructed two datasets, one in which people with dementia could have that diagnosis on the basis of either a home or research clinic study visit, and people who died without dementia had a home or research clinic study visit within two years of death (the “all data” dataset), and a second dataset limited to those who died without a diagnosis of dementia and had a research clinic visit within two years of death, and those who died with dementia had that diagnosis made at a research clinic visit (the “clinic only” dataset). Details of the neuropathology protocols have been published [17, 18]; microscopic evaluations are performed blinded to clinical information. We considered neuritic plaques as rated by CERAD criteria (2 or 3 vs. 0 or 1), neurofibrillary tangles as rated by Braak and Braak criteria (5 or 6 vs. 0–4), hippocampal sclerosis (present vs. absent), amyloid angiopathy (any vs. none), neocortical Lewy bodies (any vs. none), cerebral cortical microinfarcts (any vs. none), deep cerebral microinfarcts (any vs. none), and cystic infarcts (any vs. none).

We modeled all-cause dementia [12] as the dependent variable. We used Poisson regression adjusted for age at death, sex, and education, and used robust variance estimates. We used bootstrapping to determine whether findings were significantly different; each sample was the same size as the “clinic only” sample.

We used Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Section 1: Factors associated with volunteering for an in-clinic and MRI ancillary study

Of the 145 ACT participants invited to consider an additional study requiring a research clinic visit and an MRI, 61 (42%) volunteered and 84 (58%) did not volunteer. Characteristics stratified by volunteer status and univariate comparisons are summarized in Table 1. In multivariate analyses, only whether the most recent study visit was at home vs. in the research clinic was independently associated with volunteer status when controlling for age and sex, with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 2.51 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06, 5.93; p = 0.036). The adjusted OR for the shopping IADL was 3.65 (95% CI 0.99, 13.46, p=0.051). Shopping and home visits were highly correlated; when we put both in the model, both ORs were attenuated and neither was statistically significant.

3.2. Section 2: Importance of home visits for analyses of AD risk factors

Of the 2,581 people in the original cohort, 2,321 had ≥1 follow-up visit, and 1,781 had complete covariate data and comprise the “all data” dataset. These individuals completed 9,005 follow-up visits, with 18,063 person-years of follow-up time (10.1 years per person on average). There were 608 incident dementia cases and 479 incident AD cases.

Of the 1,781 people in the “all data” dataset, 1,369 (77%) had baseline and ≥1 follow-up visits in the clinic; they comprise the “clinic only” dataset. The remaining 392 people had no in-clinic follow-up visits. Considering only the 1,369 people who had in-clinic data, this cohort amassed 5,506 in-clinic follow-up visits with 10,969 person-years of follow-up time (8.0 years per person on average). There were 147 incident dementia cases and 117 incident AD cases (24% of all dementia and AD cases) identified following in-clinic study visits; all the remaining 461 dementia cases were identified following home visits.

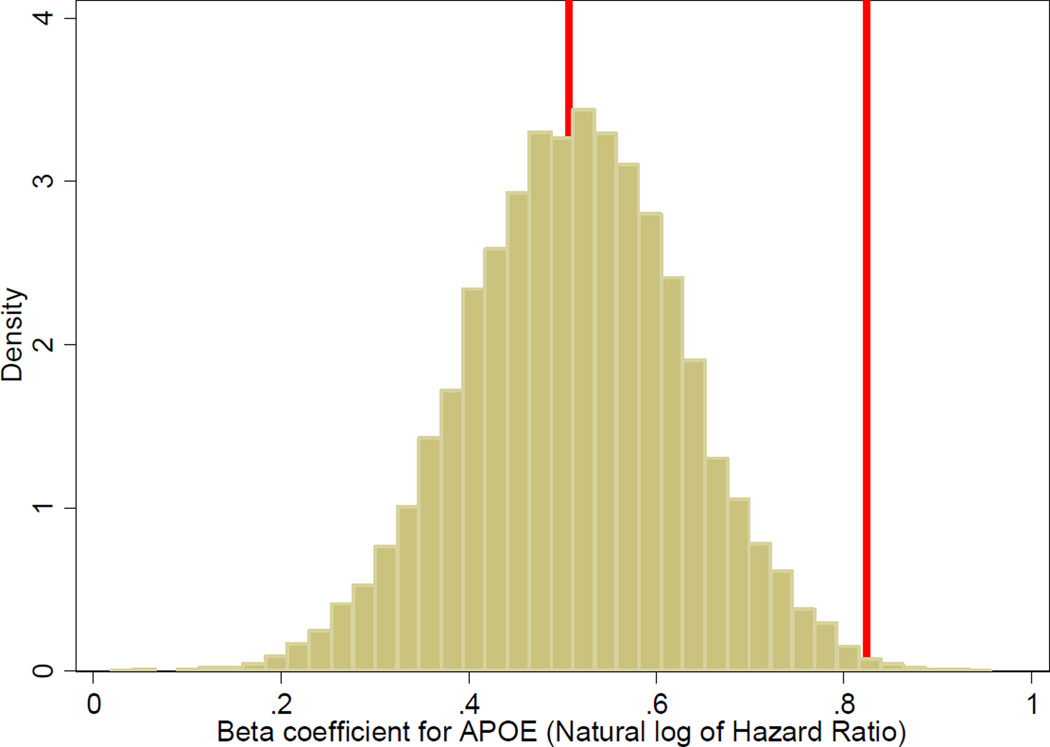

AD risk factors are shown in Table 2. With the “all data” dataset, we observed significant associations for age, education, and APOE genotype. With the “clinic only” dataset, we observed significant associations for age, cerebrovascular disease, APOE genotype, and medical comorbidity, but not education. Bootstrap results shown in the right hand column suggest differences in hazard ratios between the “all data” dataset and the “clinic only” dataset were larger than could be explained by chance alone for age, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, APOE genotype, and medical comorbidity. For example, for APOE ε4 genotype, the hazard ratio for AD was 1.66 in the “all data” dataset, and 2.28 in the “clinic only” dataset, which had fewer people and less person-time of follow-up. The bootstrap results shown in the right hand column of Table 2 (p=0.008) suggest this difference in hazard ratios was very unlikely to be due to chance (see Figure).

Figure.

Histogram of bootstrap results for association between one or more copies of APOE ε4 alleles and risk of Alzheimer’s disease*

* For each risk factor considered in Table 2, we sampled with replacement from the “all data” dataset a sample of people the same size as the “clinic only” dataset, and performed Cox regression on that dataset of the association between the risk factor and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. We captured the beta coefficients from those models; exponentiated beta coefficients from these models are hazard ratios. We repeated this procedure 10,000 times for each risk factor. This graph shows results for APOE genotype. The red vertical line at 0.507 was the result we obtained with the entire “all data” dataset; this value is the natural logarithm of 1.66. The red vertical line at 0.824 was the result we obtained with the “clinic only” dataset; that value is the natural logarithm of 2.28. The graph shows that the bootstrapping results are normally distributed with a central tendency very close to the observed value from the entire “all data” dataset; the observed result from the “clinic only” dataset is far from that value, and only a very few of the 10,000 sampled datasets had values that extreme. These 10,000 beta coefficients were used to arrive at the p-value of 0.008 shown in Table 2.

3.3. Section 3: Importance of home visits for analyses of neuropathological findings

The “all data” dataset for autopsy analyses included 347 people. Of these, 170 (49%) had dementia. In-clinic data were available in the relevant time window (within two years of death for those who died without dementia, and at the time of dementia diagnosis for those who died with dementia) for 88 people (25%); the remaining 259 people (75%) died following a home-based rather than a clinic-based study visit. Only 35 of the 170 people who died with dementia (21%) died following an in-clinic study visit; the other 135 people with dementia (79%) died following a home study visit.

Associations between neuropathological findings and dementia are shown in Table 3. With the “all data” dataset, all neuropathological findings were associated with dementia. With the “clinic only” dataset, most of the relationships were stronger, but few were statistically significant. Bootstrapping analyses suggested that differences in odds ratios for Braak stage, hippocampal sclerosis, cerebral cortical microinfarcts and cystic infarcts were larger than expected based on chance alone.

Table 3.

Section 3: Associations between neuropathological findings and all-cause dementia considering all data from the autopsy subset of the original cohort (left columns) and considering only the subset of those data collected at research clinic study visits (right columns), along with bootstrapping results (far right column)*

| All data | Clinic-only data | Bootstrap results |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finding | RR | CI | p value | RR | CI | p value | p value |

| CERAD | 1.73 | 1.35, 2.21 | <0.0001 | 1.63 | 0.88, 3.02 | 0.12 | 0.70 |

| Braak | 2.27 | 1.84, 2.79 | <0.0001 | 3.43 | 1.90, 6.19 | <0.0001 | 0.006 |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | 1.47 | 1.11, 1.95 | 0.008 | 2.28 | 1.43, 3.66 | 0.0006 | 0.034 |

| Amyloid angiopathy | 1.42 | 1.16, 1.74 | 0.001 | 1.69 | 1.05, 2.73 | 0.030 | 0.22 |

| Neocortical Lewy bodies | 1.45 | 1.04, 2.03 | 0.029 | 1.83 | 1.03, 3.27 | 0.040 | 0.33 |

| Cerebral cortical microinfarct | 1.42 | 1.15, 1.74 | 0.001 | 2.00 | 1.23, 3.25 | 0.005 | 0.018 |

| Deep cerebral microinfarct | 1.44 | 1.17, 1.76 | 0.0006 | 1.59 | 0.99, 2.57 | 0.06 | 0.48 |

| Cystic infarct | 1.55 | 1.26, 1.89 | <0.0001 | 2.35 | 1.54, 3.58 | 0.0001 | 0.004 |

Bootstrapping p values were obtained using analogous procedures to those described in the note to Table 2, except we used Poisson regression to obtain relative risks.

4. Discussion

In this report we focused on the capacity for home visits, an under-appreciated study design characteristic that may be critical for validity of dementia studies. In Section 1, we evaluated data from inviting active study participants with autopsy consents to consider a new initiative that required an in-clinic study visit. In multivariate analyses, the only salient factor associated with volunteering for the new initiative was whether the previous study visit was in the clinic or at home.

These findings led us to consider the relevance of capacity for home research study visits. We used data from ACT’s original cohort, for whom we have 20 years of follow-up data and excellent completeness of follow-up [19]. With these data we performed analyses with all of the data including those from home study visits, and repeated the same analyses limiting ourselves to the data collected at our research clinic. For our purposes, we treated results from the entire data set as accurate, and used bootstrapping analyses to determine whether findings from the clinic-only dataset were more different from those of the entire dataset than expected due to chance.

With this strategy, we considered AD risk factors (Section 2). Limiting ourselves to data collected in the clinic reduced sample size by 23%, reduced follow-up time by 39%, and reduced the number of dementia and AD cases by 76%. Power is not the only concern, however. Limiting ourselves to data collected in the clinic led to significantly over-estimating the relevance of several risk factors, including age and APOE ε4 genotype. Disparate findings for cerebrovascular disease were especially concerning. With the “all data” dataset this factor was not a significant predictor of AD (HR = 1.29, p=0.13), while with the “clinic only” dataset, the importance of this factor was significantly over-estimated (bootstrap p=0.006), and it was a significant predictor of AD (HR = 2.42, p=0.002). If we consider “all data” dataset results to be accurate, using the “clinic only” dataset would lead us to falsely identify this covariate as an AD risk factor.

In Section 3, we performed similar analyses of associations between neuropathological findings and dementia in those with autopsy data. Limiting to data collected in the clinic had large effects on power, as sample size was reduced by 75%. Limiting to data collected in the clinic also resulted in significantly over-estimating the relevance of several neuropathological findings.

Missing data lead to important challenges to inference in observational studies. Limiting ourselves to subsets of data necessarily reduces power to find associations. From the perspective of obtaining valid inference, the finding that we would come to different conclusions if we only had in-clinic data is much more concerning. Significantly discrepant findings between the “all data” and “clinic only” datasets as demonstrated by bootstrap results in Section 2 and 3 provide evidence that data missing due to the lack of home study visit capacity are missing not at random (MNAR).

This result has important implications. Results from studies with data that are MNAR are biased – they provide the wrong answer – and we do not know the direction of the bias. Compared to the “all data” dataset findings, whose results we are treating as accurate, with the “clinic only” dataset we found significantly inflated estimates for associations of several factors with risk for AD (e.g. age, APOE genotype, cerebrovascular disease) at the same time we identified other factors where lack of power led to false negative conclusions (e.g. education). Similarly, in the neuropathology analyses, missing data led to markedly reduced power, such that findings for CERAD, neocortical Lewy bodies, and deep cerebral microinfarcts were not significantly associated with dementia. At the same time, findings for Braak stage, hippocampal sclerosis, cerebrocortical microinfarcts, and cystic infarcts were significantly over-estimated compared to results from the “all data” dataset.

It may be difficult for people who are frail, physically ill, and/or cognitively impaired to travel to clinic settings, so it is not a surprise that data are missing in studies that lack home research study capacity. What may be a surprise is that we have no idea whether associations found using data from a study with only in-clinic data collection are over- or under-estimated compared to what we would find if we had more complete data by having capacity for in-home visits. If we only had data collected in a research study setting, we could not predict the magnitude or the direction of bias due to missing data.

This finding is concerning for specialty clinic-based studies or community-based studies that require research clinic study visits. Whether phone-based ‘visits’ could also be used should be studied.

As shown in Section 1, about a quarter (17 of 64, 27%) of those we invited to consider the new initiative whose previous study visit had been at home did volunteer. This finding could be used to suggest that our analyses may overstate the case to some extent, as about a quarter of those who in fact had home study visits may have been able to attend a research clinic study visit. A hypothetical in-clinic only study could categorize participants in each wave as “not reluctant in-clinic attendees,” “reluctant in-clinic attendees” who would have chosen a home visit if that had been available, and “unable to attend clinic”. Studies that include capacity for home visits obtain data from all three groups, but cannot distinguish between the second group (who could have attended an in-clinic visit if that was the only option) and the third group, since both of those groups of people would be seen at home. Studies that lack capacity for home visits obtain data only from the first two groups, and do not typically distinguish between those groups. Even if people in the second group and people in the third group are very similar to each other (which we strongly doubt but do not know), and even if such studies ascertain how easy or difficult it was for participants to come to clinic, these results are not typically used in analytic plans to try to address the challenges that arise from the data from the third group that are MNAR. These considerations may be responsible for some of the important differences identified in results from specialty clinic convenience samples compared to those from population-based studies [20, 21], though the relevance of home study visit capacity had not been previously emphasized.

An intriguing possibility is raised by our finding in section 1 that needing help with shopping performed similarly to home vs. clinic study visits. For studies that lack home study visit capacity, it may be possible to develop an analytic scheme that incorporates weights based on modeling the shopping IADL that could in part address challenges raised by data that are MNAR.

Our results in Section 2 suggest the relevance of APOE ε4 genotype to AD risk may be over-estimated in studies that only include research clinic data collection. An earlier report that compared research clinic vs. community-based dementia cases found higher proportions of research clinic cases had one or more APOE ε4 alleles [22]. A subsequent study demonstrated that APOE genotype was less useful in the diagnostic workup of people from a community-based setting than had been reported previously in the literature derived from specialty clinic convenience samples [23]. Our current findings provide further support for the notion that the importance of APOE genotype may be somewhat attenuated in samples that most closely reflect the underlying population of community-dwelling older people compared with samples that are limited to specialty clinic convenience samples. It should be appreciated that APOE genotype is an important predictor of AD risk in our study; our finding was that the magnitude of that association was significantly larger from the “clinic only” subset of our participants.

Our findings should be considered in the context of limitations. There is some attrition despite including home visits. Our completeness of follow-up index [19] is exemplary but not perfect. It is not known whether similar healthy participant bias may influence the results that we observe. We doubt that would be the case due to the overall low rates of study attrition, but cannot rule out that possibility. If anything, these considerations reinforce our conclusion regarding the importance of home visit capacity for collecting data from older adults, as we suspect that differences between clinic-only parameter estimates and those that would have been obtained from the complete data – including not only people with home visits (evaluated in our study but not in specialty clinic convenience sample studies) but also people who dropped out of the study (not evaluated in either our study or specialty clinic convenience sample studies) – would be even larger than those we found. Unmeasured and residual confounding are always possibilities in observational studies. Underrepresented ethnic diversity of our sample is somewhat restricted, though the demographic makeup of our study cohort reflects that of King County. Home visit capacity has been specifically advocated as a means of increasing underrepresented ethnic participation in dementia studies [2]; we suspect our conclusions might be stronger in settings with higher ethnic minority representation.

Our findings strongly support the importance of home visit data collection capacity in the design of observational studies of dementia and neuropathology in older adults. Studies that only include research clinic data collection may lead to biased conclusions. These results suggest that new studies at the design stage should consider incorporating home visit data collection capacity despite its expense and administrative complexity. Existing studies should routinely report on this important detail of study design in reports of study findings. Studies that lack home study visit capacity should specify that as a possible limitation, and should be cautious in interpreting study findings.

Research in Context.

Systematic review

The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (e.g., PubMed) sources. A few publications address the importance of home research study visit capacity for studies of older people. These relevant citations are appropriately cited. None focused on validity of findings from dementia studies.

Interpretation

Our findings suggest home research study visit capacity is important for power. We also found that home research study visit capacity may be important for validity, as extrapolating from in-clinic only data led to erroneous conclusions regarding AD risk factors and the relevance of neuropathological findings on dementia risk.

Future directions

The manuscript suggests that home research study visit capacity should be strongly considered at the study design stage. Reports from all studies should include information about whether the study had home research study visit capacity. Studies that lack home research study visit capacity should be very cautious in drawing conclusions.

Acknowledgments

Study funding for the ACT study was from AG-06781 (Multiple PIs: E Larson and P Crane). Meredith Pfanschmidt, Sheila O’Connell, Patti Boorkman, Lisa Millspaugh, and Tiffani Rivara have conducted home-based research study visits. Autopsies and some analyses were also funded by P50 AG-05136 (PI: T Montine)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: ACT: Adult Changes in Thought. AD: Alzheimer’s disease. CASI: Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument. CERAD: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. HR: Hazard ratio. MNAR: Missing not at random.

Contributor Information

Paul K. Crane, Email: pcrane@uw.edu.

Laura E. Gibbons, Email: gibbonsl@uw.edu.

Susan M. McCurry, Email: smccurry@u.washington.edu.

Wayne McCormick, Email: mccorm@uw.edu.

James D. Bowen, Email: James.Bowen@swedish.org.

Joshua Sonnen, Email: joshua.sonnen@path.utah.edu.

C. Dirk Keene, Email: cdkeene@uw.edu.

Thomas Grabowski, Email: tgrabow@uw.edu.

Thomas J. Montine, Email: tmontine@uw.edu.

Eric B. Larson, Email: larson.e@ghc.org.

References

- 1.Strotmeyer ES, Arnold AM, Boudreau RM, Ives DG, Cushman M, Robbins JA, et al. Long-term retention of older adults in the Cardiovascular Health Study: implications for studies of the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:696–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wrobel AJ, Shapiro NE. Conducting research with urban elders: issues of recruitment, data collection, and home visits. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13(Suppl 1):S34–S38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritchie CS, Dennis CS. Research challenges to recruitment and retention in a study of homebound older adults: lessons learned from the nutritional and dental screening program. Care Manag J. 1999;1:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komulainen K, Ylostalo P, Syrjala AM, Ruoppi P, Knuuttila M, Sulkava R, et al. Preference for dentist's home visits among older people. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorresteijn TA, Rixt Zijlstra GA, Van Eijs YJ, Vlaeyen JW, Kempen GI. Older people's preferences regarding programme formats for managing concerns about falls. Age Ageing. 2012;41:474–481. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson JC, Pirraglia PA, Wells MT, Charlson ME. Attrition in longitudinal randomized controlled trials: home visits make a difference. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludman EJ, Fullerton SM, Spangler L, Trinidad SB, Fujii MM, Jarvik GP, et al. Glad you asked: participants' opinions of re-consent for dbGap data submission. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2010;5:9–16. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.3.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Teri L, Schellenberg GD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1737–1746. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Teri L, Crane P, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:73–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crane PK, Walker R, Hubbard RA, Li G, Nathan DM, Zheng H, et al. Glucose levels and risk of dementia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:540–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, Imai Y, Larson E, Graves A, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6:45–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001602. discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, Meenan RT, Bachman DJ, O'Keeffe Rosetti MC. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model. Med Care. 2003;41:84–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKhann G. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:72–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Crane PK, Haneuse S, Li G, Schellenberg GD, et al. Pathological correlates of dementia in a longitudinal, population-based sample of aging. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:406–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Haneuse S, Woltjer R, Li G, Crane PK, et al. Neuropathology in the Adult Changes in Thought Study: A Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet. 2002;359:1309–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnhart RL, van Belle G, Edland SD, Kukull W, Borson S, Raskind M, et al. Geographically overlapping Alzheimer's disease registries: comparisons and implications. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1995;8:203–208. doi: 10.1177/089198879500800401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brayne C. A population perspective on the IWG-2 research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:532–534. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuang D, Kukull W, Sheppard L, Barnhart RL, Peskind E, Edland SD, et al. Impact of sample selection on APOE epsilon 4 allele frequency: a comparison of two Alzheimer's disease samples. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:704–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuang D, Larson EB, Bowen J, McCormick W, Teri L, Nochlin D, et al. The utility of apolipoprotein E genotyping in the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease in a community-based case series. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:1489–1495. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.12.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]