Abstract

Helicobacter pylori is a successful pathogen of the human stomach. Despite a vigorous immune response by the gastric mucosa, the bacterium survives in its ecological niche, thus favoring diseases ranging from chronic gastritis to adenocarcinoma. The current literature demonstrates that high-output of nitric oxide (NO) production by the inducible enzyme NO synthase-2 (NOS2) plays major functions in host defense against bacterial infections. However, pathogens have elaborated several strategies to counteract the deleterious effects of NO; this includes inhibition of host NO synthesis and transcriptional regulation in response to reactive nitrogen species allowing the bacteria to face the nitrosative stress. Moreover, NO is also a critical mediator of inflammation and carcinogenesis. In this context, we review the recent findings on the expression of NOS2 in H. pylori-infected gastric tissues and epithelial cells, the role of NO in H. pylori-related diseases and H. pylori gene expression, and the mechanisms whereby H. pylori regulates NO synthesis by host cells.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, Helicobacter pylori, Polyamines, Gastric cancer

Infection with Helicobacter pylori

More than half of the world’s human population carries Helicobacter pylori, a Gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium that specifically colonizes the stomach. H. pylori typically coexists with its host, who may even benefit from this colonization notably in childhood [1]. However, long-term infection may cause diseases including chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer. The persistence of the bacterium within the hostile, acidic ecologic niche of the stomach is principally due to the activity of the H. pylori urease that neutralizes gastric acidity by generating ammonium from urea. Moreover, the common trait of H. pylori strains that have increased risk of inducing gastric adenocarcinoma is the expression of specific virulence genes including the protein cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) [2] and the vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) [3] (Box1). Environmental components [4] and host factors [5] have been also shown to be involved in the outcome of H. pylori infection. But, whether host and pathogen genomic variations in a spatio-temporal axis are associated with the development of gastric diseases, overall the clinical outcome of H. pylori infection-induced gastric carcinogenesis is determined by the progression along the histologic cascade from non-atrophic gastritis to adenocarcinoma [6].

Box 1. H. pylori CagA and VacA.

CagA is a bacterial factor that is part of the cag pathogenicity island and is injected into human epithelial cells through a type IV secretion system. CagA is then sequentially phosphorylated by the host c-Src and Abl kinases [83] and dysregulates the homeostatic signal transduction of gastric epithelial cells [84]. This results in persistent inflammation and malignancy by loss of cell polarity, modulation of apoptosis, and chromosomal instability [2].

VacA contributes to H. pylori pathogenesis by regulating inflammatory process [85] and by damping autophagic cell death, thus favoring gastric colonization and oxidative damage [3]. Although the contribution of VacA to gastric dysplasia has not been directly demonstrated using animal models, epidemiological studies have emphasized a correlation between the vacA gene structure and severity of H. pylori-related diseases. More precisely, the signal region s1 and the middle regions m1 of the vacA gene are present in strains associated with increased risk for developing peptic ulcers and/or gastric cancer, compared to s2 or m2 strains.

The pathogenesis of H. pylori-induced diseases is mediated by the infiltration, activation, and persistence of cells of the innate and chronic immune response. Furthermore, the non-specific defense program of gastric epithelial cells and macrophages against H. pylori leads to the production of nitric oxide (NO), a ubiquitous free radical synthesized by the enzyme NO synthase (NOS) through the oxidation of L-arginine. The activity of the inducible NOS (NOS2) enzyme is independent of Ca2+ and produces a high-output of NO for a long period of time; this enzyme is regulated at the transcriptional level in numerous cells types after activation by cytokines or pathogen-associated molecular patterns. The present review synthesizes knowledge on the interactions that occur between H. pylori and NO, with respect to expression of NOS2 in infected tissues and cells, biological significance of NO synthesis for the host and the bacterium, and occurrence of NO synthesis regulation.

Infected Gastric Tissues: Where Is NOS2?

Numerous investigations have evidenced an increase of Nos2 mRNA expression in the gastric tissues of H. pylori-infected patients [7-9], independently of the cagA status of the bacteria [10]. The NOS2 gene is more highly expressed in the antrum part of the stomach, where H. pylori colonization has been shown to be greater, than in the body [7, 11], suggesting that NOS2 expression is directly related to the presence of the bacteria. In support of this contention, by immunohistochemistry, NOS2 is less expressed in H. pylori-negative gastritis than in infected patients [12], and in the gastric mucosa after the eradication of H. pylori by antibiotic-based triple therapy when compared to before the treatment [11, 13-15].

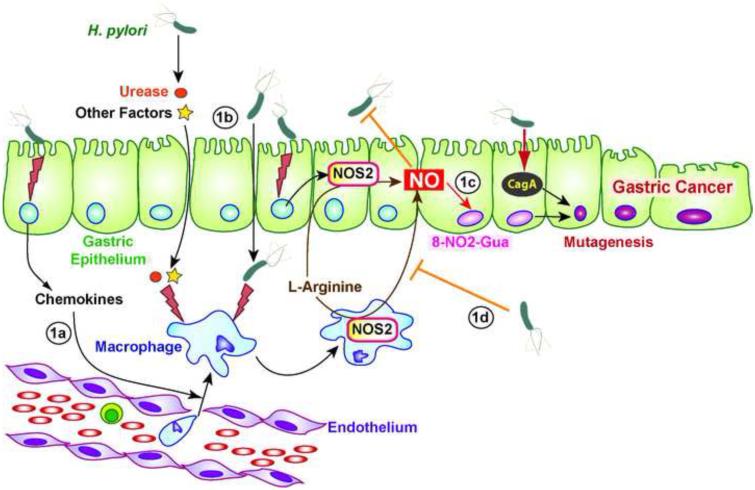

While there is a consensus about NOS2 expression in gastric biopsies during H. pylori infection, the cellular distribution of the protein has been questioned by different studies (Figure 1, Key Figure). Fu et al. immunolocalized NOS2 protein in epithelium, endothelium, and lamina propria inflammatory cells of the stomach of patients in the U.S. showing H. pylori gastritis [7]. Similarly, one third of Japanese patients with H. pylori-positive gastric ulcer exhibited NOS2 staining in both epithelium and infiltrating inflammatory cells at the margin of active gastric ulcers [16]. But in the same study, the authors showed NOS2 reactivity mainly in the lamina propria of 46% of the infected patients [16]. Similarly, other investigations have reported NOS2 only in inflammatory cells of the mucosa of H. pylori-infected patients, including polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mononuclear cells [12, 13, 15]. The localization of the gastric biopsies or the state of the disease may explain these differences, but also the varying antibodies used for immunohistochemistry could also be an important consideration. Interestingly, nitrotyrosine, which indicates the nitration of tyrosine by peroxynitrite (ONOO−) generated from NO and O2−, is immunodetected in epithelial cells and macrophages, even in studies in which NOS2 was found only in inflammatory cells [12, 13, 16]. This suggests that NO is effectively synthesized from NOS2 and that reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI) target not only the NO-producing cells, but also the cells surrounding NOS2-expressing macrophages, thus providing a rationale for a potential biological effect in the infected tissues.

Figure 1.

Key Figure: H. pylori Infection in an NO World. H. pylori stimulates gastric epithelial cells and thus induces an innate response characterized by the production of chemokines, which leads to the recruitment of myeloid cells, including macrophages, in the gastric mucosa (1a). H. pylori-derived factors, such as urease, or the bacterium itself stimulate NOS2 expression in macrophages and in gastric epithelial cells (1b). NO releases by these activated cells has a cytotoxic effect on H. pylori and provokes the formation of 8-nitroguanine (8-NO2-Gua; 1c). The cellular changes induced by the oncoprotein CagA and the mutagenesis reinforced by the activity of 8-NO2-Gua may contribute to the development of gastric cancer. Ultimately, H. pylori regulates NO production by numerous strategies (1d).

Animal models have provided a strong tool to study H. pylori-associated inflammation and carcinogenesis. Thus, increased Nos2 mRNA has been observed in isolated gastric macrophages of H. pylori SS1-infected C57BL/6 mice after 4 months [17, 18] and in macrophages and monocytes of C57BL/6 male Big Blue transgenic mice infected for 6 months with the same strain [19]. However, in the latter study the authors show that Nos2 mRNA is not detected in mice infected for 12 months and propose that a regulation of H. pylori factors involved in Nos2 induction may occur in a long-term infection [19]. The expression of Nos2 mRNA is also induced in Mongolian gerbils infected with H. pylori for 2 weeks [20] or 3 months [21]. Finally, like in humans, a reduction of Nos2 mRNA is observed with the eradication of H. pylori in infected INS-GAS mice [22], which are transgenic animals overexpressing gastrin that develop accelerated gastric cancer after Helicobacter infection. Furthermore, NOS2 colocalizes with F4/80+ macrophages, but not with CD11c+ dendritic cells, in H. pylori-infected mice [18, 23].

The Mechanism of NOS2 Induction in Host Cells by H. pylori

Although live H. pylori or its lipopolysaccharide (LPS) fails to induce NO production by human macrophages [24, 25], several groups have demonstrated NOS2 mRNA induction in human gastric epithelial cell lines after H. pylori infection [26-28]. However, in several of these studies, either: (i) the level of NOS2 induction is very low [26, 29]; (ii) the production of RNI does not reflect NOS2-dependent high-output NO generation – e.g., ~ 6 μM NO2− produced by AGS cells infected for 24 h with H. pylori [27]; or (iii) NO production is not shown in these papers [26, 28]. These investigations could also have increased our knowledge about the molecular mechanism by which H. pylori might induce NOS2 in epithelial cells, but there is a strong discrepancy observed between the reports. While authors show that p38 and ERK1/2 [26] and the transcription factor NF-κB [30] are involved in H. pylori-induced-NOS2 in Hs746T and MKN45 cells, Cho et al. have demonstrated that H. pylori strain HP99 induces NOS2 mRNA and protein expression in AGS cells through a mechanism implicating a Ras-AP-1 signaling pathway [27]. Interestingly, epigenetic modifications, including histone demethylation and acetylation and release of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 at the promoter region favors NOS2 transcription in MKN28 cells infected with wild-type (WT) H. pylori or a Cag pathogenicity island−/VacA− mutant strain [28]. To our knowledge, only one report has shown that a combination of H. pylori LPS and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) stimulates Nos2 expression at the transcriptional and protein level in the immortalized murine gastric epithelial cell line GSM06 [31].

However, the effect of H. pylori on murine macrophages has been extensively studied. The novelty of the H. pylori–innate immune system response crosstalk resides mainly in the fact that H. pylori LPS is not effective in inducing macrophage NO generation [25, 32, 33], in contrast to the endotoxin of other Gram-negative bacteria [32, 34]. When live H. pylori is in direct contact with murine macrophages, a strong NOS2 induction and a high level of NO production are observed in the cells [32, 35]. In this context, different mutant strains of H. pylori lacking CagA, the type IV secretion system, VacA, catalase, the outer membrane proteins AlpAB, or urease induce the same level of NO production than the parental strain [25, 36, 37], suggesting that more than one bacterial product can stimulate NOS2 expression after phagocytosis; however, when H. pylori and macrophages are physically separated by a filter, a urease mutant fails to activate NOS2 [36], demonstrating that urease released by H. pylori is a potent inducer of NO production (Figure 1).

Role of High-output NO Production on H. pylori-related Pathological Processes

Its ability to freely diffuse across the producing cells and its strong reactivity as a radical molecule confers to NO a critical role in homeostasis and pathophysiological processes. Although it has been reported that the level of gastritis and the Th1 and innate responses are similar in WT and Nos2-deficient mice during H. pylori infection [38, 39], several lines of evidence point toward an effect of NO on H. pylori-mediated carcinogenesis (Figure 1). First, histological analyses have revealed increased NOS2 protein level, nitrotyrosine immunostaining, and oxidative DNA damage in patients with gastric cancer compared to individuals with H. pylori gastritis [12, 40]; moreover, cancer cells express more NOS2 than noncancerous foveolar epithelial cells or mucosal neck cells, mainly in older patients [40]. Similarly, it has been observed that Nos2 expression in macrophages parallels the mutation frequency in gastric epithelial cells in Big Blue transgenic mice [19]. Second, in WT mice treated with the carcinogen N-methyl-N-nitrosourea and then infected with H. pylori for 50 weeks, NOS2 is expressed in adenocarcinoma and inflammatory cells [41]; moreover gastric adenocarcinoma incidence is significantly reduced by more than 50% in Nos2–/– mice compared to WT animals [38, 41]. Accordingly, DNA fragmentation is observed in WT mice, but not in Nos2–/– mice infected with H. pylori SS1, despite the same level of acute inflammation [38]. Third, a long (CCTTT) repeat (> 13) in the 5′ promoter region of the NOS2 gene, which increased mRNA expression, has been associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer in H. pylori-infected Japanese patients [42, 43], providing a rationale for the involvement of NO in H. pylori-associated carcinogenesis.

NO and certain RNI are considered to be potent mutagens. When levels of RNI surpass the antioxidant capacity, they can cause nitrosative and nitrative damage to nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids. Hence, H. pylori gastritis is associated with enhancement of gastric gland epithelial cell content of 8-nitroguanine [44, 45], one of the major products formed by the reaction of guanine with ONOO− [46], which facilitates G:C→A:T transversions in DNA and is therefore potentially mutagenic (Figure 1). Interestingly, this effect on DNA results in one of the most common mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene in early phases of human gastric carcinogenesis [47]. However, further studies are required to determine the causal relationship between NO-dependent DNA damage and gastric cancer during H. pylori infection.

Apoptosis is increased in human gastric epithelial MKN45 [48] and AGS [29] cells pretreated with IFN-γ and then infected with H. pylori; a NOS inhibitor blocks apoptosis, which led to the conclusion that H. pylori-induced apoptosis is NO-dependent [29, 48]. However, the level of NOS2 mRNA is not convincing and NO generation is not shown in these papers. Nonetheless, in vivo experiments showing that infected Nos2–/– mice have less gastric mucosal apoptosis than WT [38] demonstrate that NO could play a role in H. pylori-induced cell death in mice. On the contrary, it has been shown that an NO donor, S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine, inhibits H. pylori-induced caspase-3 activity and apoptosis in MKN-45 epithelial cells [30], demonstrating that exogenous NO decreases apoptosis. Macrophage apoptosis in response to H. pylori is mediated by the generation of hydrogen peroxide through the arginase-2 (ARG2)-ornithine decarboxylase (ODC)-spermine oxidase metabolic pathway [49, 50] and is NO-independent [49]. Thus, the role of NO in H. pylori-induced apoptosis appears to cell and model specific.

H. pylori Response to NO Exposure

Pathogenic bacteria have elaborated strategies to resist the direct effect of oxidative and nitrosative stress. Intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli or Salmonella enterica express NO sensors that directly regulate the transcription of genes implicated in virulence [51, 52] and resistance to large amount of RNI [53, 54]. Therefore, intra- or extra-cellular pathogenic bacteria exhibit a strong resistance to NO challenge [51, 55]. However, H. pylori is more sensitive to NO and RNI, including ONOO−, than other enteric pathogens [56, 57]; moreover, it has been shown in vitro that activated macrophages inhibit the growth of H. pylori through an NO-dependent pathway [35, 58, 59]. This anti-proliferative effect may be mediated by the irreversible inhibition of H. pylori respiration by NO and ONOO− [60]. Of note, the H. pylori urease subunit, UreA, can be S-nitrosylated by RNI, leading to the inhibition of enzymatic activity [61]. Interestingly, Kuwara et al. have reported that CO2 formed by urease activity reacts with ONOO– to form nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONOOCO2−), which is converted to the non-toxic metabolite, NO3− (Figure 2), thus suppressing the deleterious effect of RNI on H. pylori survival [57].

Figure 2.

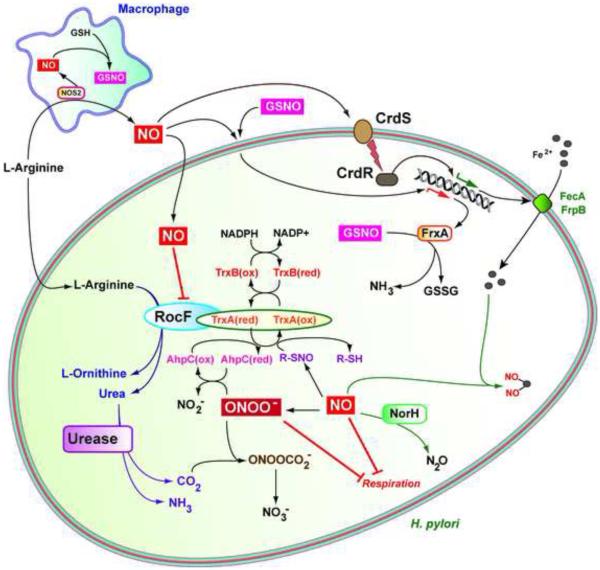

RNI Detoxification in H. pylori. High-output NOS2-dependent NO production by macrophages is released outside the cells and may affect the bacteria at distance from producing cells or is converted in GSNO to target phagocytized H. pylori. RNI inhibit H. pylori respiration and the activity of the arginase RocF, thus decreasing the synthesis of the urease substrate, urea. H. pylori counteracts the deleterious effect of RNI using the NO reductase NorH, the GSNO reductase FrxA, the thioredoxin TrxA that also serves as a chaperone for RocF, and the CrdSR-dependent upregulation of FecA and FrpB that are involved in iron transport. ONOO− detoxification occurs through the urease-dependent production of CO2 and the peroxiredoxin AhpC.

The susceptibility of H. pylori to NO is sustained by the lack of the major NO sensors, e.g. NsrR or NorR, harbored by other pathogenic bacteria [53, 62] and lack of detoxification proteins such as Hmp [63]. However, sublethal doses of RNI may impact the transcriptome of H. pylori, in ways that may allow H. pylori to escape some of the effects of RNI. The two-component system CrdS–CrdR is activated when H. pylori is exposed to NO donors and the ΔcrdS/R strains are more susceptible to NO than the WT [56], suggesting that CrdS is a sensor for nitrosative stress and that CrdR responds to this challenge. The NO-induced CrdSR-dependent genes include, notably, those encoding proteins involved in iron transport [56], but no genes specifically involved in direct NO detoxification; thus maintaining iron homeostasis may be a way for H. pylori to defend against nitrosative stress (Figure 2). However, the mechanism by which CrdS responds to NO remains unknown.

Justino et al. have identified two H. pylori proteins that are potent reducer of NO: First, the protein Hp0013, renamed NADPH-dependent NO reductase of H. pylori (NorH), metabolizes NO through an NADPH-dependent enzymatic activity and allows the resistance of H. pylori to S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and the NO donor dipropylenetriamine-NONOate [64]. Second, the gene frxA (HP0642) encodes a GSNO reductase that is transcriptionally induced by various NO donors, but reduces only GSNO into glutathione (GSH), supporting the concept that this enzyme plays a major function in the survival of phagocytized H. pylori [65]. Consequently, NorH and FrxA attenuate the NO-dependent H. pylori killing by macrophages ex vivo and also favor the survival of H. pylori in vivo [64; 65] (Figure 2), further indicating that NO effectively attenuates H. pylori growth in the stomach.

Two thioredoxins (Trx) exist in H. pylori: TrxA (or Trx1) and TrxC (also called Trx2). While TrxC is more involved in preventing oxygen-dependent damage [66], TrxA dampens the nitrosative attack on H. pylori [67, 68]. The deletion of trxA yields a diminution of stomach colonization by H. pylori [66]. Interestingly, a proteomic analysis revealed that 38 proteins are regulated in H. pylori exposed to the NO donor sodium nitroprusside [69]. Among those induced by NO, more than half correspond to antioxidant and stress proteins [69], as expected. Notably, the Trx reductase TrxR, also identified as TrxB, is upregulated by NO and that the deletion of the gene encoding this protein enhances the susceptibility of H. pylori to RNI [69]. Moreover, TrxA is also a reductant for the H. pylori peroxiredoxin AhpC [67], which converts ONOO– into NO2− [70], further demonstrating the essential role of the TrxA/TrxR pathway in RNI resistance (Figure 2). This is reinforced by the fact that H. pylori lacks the glutathione system, which is essential for cellular thiol:disulfide balance and survival under oxidative stress in many Gram-negative bacteria [71].

These findings underline that the resistance of H. pylori to RNI is mediated by unique mechanisms, including in comparison with other pathogenic bacteria of the gastrointestinal tract.

Regulation of NO Production by H. pylori

Years of co-evolution between H. pylori and the host has forced the bacterium to adapt to the immune response, and more particularly to limit macrophage NO production by mechanisms involving the regulation of NOS2 gene expression and L-arginine-dependent pathway (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

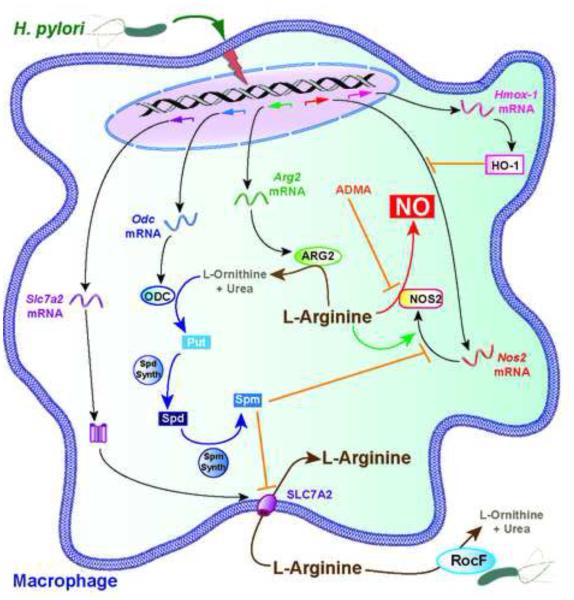

Regulation of Macrophage NO Production by H. pylori. The infection of murine macrophages by H. pylori results in the expression of Slc7a2, Odc, Arg2, Hmox-1 (the gene encoding HO-1), and Nos2 mRNA. L-arginine uptake is supported by SLC7A2, promotes NOS2 translation, and is required for NO production. ARG2 and H. pylori arginase RocF deplete intracellular and extracellular L-arginine, respectively, thus decreasing the synthesis of NOS2 and generation of NO. Spermine (Spm), which is synthesized through the ARG2-ODC pathway, inhibits SLC7A2-dependent L-arginine uptake and thus NOS2 translation and activity. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) is generated during H. pylori infection and is a natural NOS2 inhibitor. Abbreviations: Put, Putrescine; Spd, Spermidine.

The enzyme heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is induced in H. pylori-infected macrophages through a CagA-dependent process involving signal transduction through p38-NRF-2, and in gastric myeloid cells of patients with H. pylori gastritis or of mice experimentally infected [72]. HO-1 expression results in an attenuation of NOS2 mRNA expression [72]. Consequently, macrophages from HO-1 null mice produce more NO and animals are less colonized by H. pylori [72].

H. pylori also induces ARG2, but not arginase-1, through an NF-κB-dependent pathway [73]. Arginases are enzymes that catabolize L-arginine into urea and L-ornithine and are in competition with NOS2 for substrate availability. In H. pylori-infected macrophages, blocking ARG2 activity with a specific inhibitor results in increased NO production [58], highlighting that the induction of the arginase metabolic pathway by the bacterium is a first way of controlling NO production. Moreover, H. pylori stimulates the synthesis of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous NOS2 inhibitor [74]; H. pylori-infected patients have increased ADMA in the gastric tissue and serum, and this level is reduced with H. pylori eradication [75, 76]. Thus, treatment of rat duodenum with an H. pylori water extract leads to ADMA synthesis and inhibits NO-mediated alkaline secretory response to luminal acid [74], thus potentially increasing gastric mucosal injury.

Importantly, the arginase product L-ornithine is converted by ODC into the first polyamine putrescine, which is then catabolized to spermidine and spermine. Although ODC is mainly regulated at the post-transcriptional level in many cell types, Odc mRNA expression is increased in murine macrophages infected in vitro with H. pylori [73] and in gastric macrophages of infected mice and humans [17], and this favors the synthesis of the three polyamines [17, 73]. Spermine blocks NOS2 translation in murine macrophages, without regulating the expression of the gene [77]. The pharmacological inhibition of ODC by difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) or Odc gene silencing results in increased NOS2 protein expression and NO generation, and consequently H. pylori killing [77]. Of note, not only ODC is an enzyme that controls NO production; macrophages from Arg2-deficient mice express more NOS2 protein, produce more NO, and are more effective in killing H. pylori than WT macrophages [18].

The intracellular bioavailability of L-arginine depends on the expression of the L-arginine transporter solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 (SLC7A2), also called cationic amino acid transporter 2. The expression of this transporter is induced in H. pylori-infected macrophages in vitro and gastric macrophages of mice and humans with H. pylori gastritis, thus increasing L-arginine uptake [17]. Moreover, increased intracellular L-arginine concentration favors NOS2 translation upon H. pylori infection, independent of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor alpha [78]. All together, these data indicate that H. pylori should activate NO production by macrophages.

However, spermine synthesized by the ARG2/ODC metabolic pathway, or added exogenously, inhibits L-arginine uptake, and consequently NOS2 translation [17]. Blocking Odc mRNA expression or ODC activity favors L-arginine entry in macrophages, but does not regulates Slc7a2 mRNA expression or SLC7A2 protein level [17], providing a rationale for the assumption that spermine is an inhibitor of SLC7A2 activity. From this, we speculate that the induction of SLC7A2 is an innate response of macrophages to favor NO production in order to eliminate pathogens, whereas the production of polyamines is an undesirable effect stimulated by H. pylori to counteract NOS2 translation. In this context, the identification of the bacterial and cellular signals leading to macrophage ODC induction by H. pylori would be helpful to develop strategies aimed at restoring NO-dependent macrophage function (see Outstanding Questions).

In accordance with these in vitro and ex vivo experiments there is (i) increased NOS2 protein by flow cytometry, (ii) enhanced NO production, shown by measurement of NO release and by in situ nitrotyrosine staining, and (iii) decreased H. pylori colonization in Arg2 knockout mice or in animals treated with DFMO [17, 18]. However, the genetic ablation of Arg2 results in increased gastritis [18], whereas a reduction of gastric inflammation and histological damage is observed with DFMO treatment [17]. However, this could be due to a collateral effect of DFMO, which reduces H. pylori growth [79]. This issue should be resolved by the analysis of H. pylori infection in myeloid-specific Odc knockout mice, which is ongoing in our laboratory.

The last stratum of regulation of host NO production by H. pylori corresponds to the direct effect of the bacterial arginase, RocF, initially described to be involved in protection of the bacteria against acidic conditions [80]. A WT strain of H. pylori, but not the arginase mutant rocF−, depletes L-arginine from the extracellular milieu in conditions that mimics the L-arginine concentration in vivo, e.g. 0.1-0.2 mM. Thus, the production of NO is enhanced when macrophages are co-cultured with a rocF mutant strain of H. pylori compared to the parental WT strain, without affecting Nos2 mRNA expression [35]. Consequently, the arginase-deficient H. pylori is more effectively killed by an NO-dependent pathway than the WT strain [35], emphasizing the critical role of arginase in H. pylori persistence in the gastric tissues. Not only does the bacterial arginase compete with the host NOS2 for L-arginine availability, but the depletion of L-arginine also results in reduced NOS2 translation since this amino acid is essential for the expression of the NOS2 protein [78]. As a striking example of the evolutionary arms race, it has been demonstrated that NO inhibits the activity of RocF [68], which should favor NOS2 translation and NO production (Figure 3); but H. pylori limits this effect of NO through the protein TrxA that acts as an anti-nitrosative chaperone for RocF [68] (Figure 2).

Hence, H. pylori has elaborated strategies to dampen NO production by macrophages, principally by decreasing L-arginine bioavailabilty for host cells. It will be of interest to now determine whether the same regulatory mechanisms occur in gastric epithelial cells.

Concluding Remarks

A particular crosstalk, which reflects thousands of years of coevolution [81], exists between H. pylori and host-derived NO. On one hand, the expression of NOS2 in myeloid cells through a pathway activated by the H. pylori urease, a unique feature in the bacterial kingdom, could be considered as a mechanism developed by the host to respond to a highly abundant protein of a bacterium exhibiting a low endotoxic activity [82]. On the other hand, H. pylori, which possesses a limited arsenal to fight NO challenge, has elaborated strategies to block NOS2 expression and NO production by the host in order to enhance its own survival. Furthermore, because evidence suggests that NO is involved in gastric cancer development, the limitation of NO production by H. pylori could even be envisioned as a collateral evolutionary process to reduce carcinogenesis and increase life expectancy of the infected host.

Outstanding Questions.

What are the H. pylori factors involved in the expression of ARG2 and ODC, which counter the induction of NOS2?

What is the evolutionary benefit for H. pylori of limiting NO production rather than resisting RNI?

By which molecular mechanisms do RNI contribute to carcinogenesis during H. pylori infection? Can further evidence for the role of NOS2-derived NO in humans be determined by investigation of populations at high-risk versus low-risk for gastric cancer?

Trends Box.

Macrophages are an important source of NOS2-dependent NO production in gastric tissues of H. pylori-infected humans and in experimental animal models.

Animal models, nitrosative damage in gastric epithelial cells of H. pylori-infected patients, and molecular epidemiology demonstrate that NO is involved in H. pylori-mediated carcinogenesis. Several unique proteins, such as the NO reductase, NorH, and biochemical pathways, including metal acquisition or urease-dependent synthesis of CO2, confer to H. pylori a partial resistance to reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI).

The lack of major effectors allowing resistance to high concentrations of RNI in H. pylori is compensated by a strong ability to inhibit host cell NO production. H. pylori dampens macrophage NO synthesis by transcriptional and translational regulation of NOS2 expression and control of L-arginine substrate availability.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01DK053620, R01AT004821, R01CA190612, P01CA028842, and P01CA116087 (to K.T.W.), a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant I01BX001453 (to K.T.W.), the Thomas F. Frist Sr. Endowment (K.T.W.), the Vanderbilt Center for Mucosal Inflammation and Cancer (K.T.W. and A.P.G.) and the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center, funded by P30DK058404 (K.T.W.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: ancient history, modern implications. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:2475–2487. doi: 10.1172/JCI38605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umeda M, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA causes mitotic impairment and induces chromosomal instability. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22166–22172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raju D, et al. Vacuolating cytotoxin and variants in Atg16L1 that disrupt autophagy promote Helicobacter pylori infection in humans. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1160–1171. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noto JM, et al. Iron deficiency accelerates Helicobacter pylori-induced carcinogenesis in rodents and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:479–492. doi: 10.1172/JCI64373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider BG, et al. DNA methylation predicts progression of human gastric lesions. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1607–1613. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correa P, Piazuelo MB. The gastric precancerous cascade. J. Dig. Dis. 2012;13:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu S, et al. Increased expression and cellular localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase 2 in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1319–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li CQ, et al. Increased oxidative and nitrative stress in human stomach associated with cagA+ Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammation. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2001;46:836–844. doi: 10.1023/a:1010764720524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatemichi M, et al. Enhanced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in chronic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1998;27:240–245. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199810000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Son HJ, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in gastroduodenal diseases infected with Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2001;6:37–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antos D, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression before and after eradication of Helicobacter pylori in different forms of gastritis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2001;30:127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goto T, et al. Enhanced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in gastric mucosa of gastric cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:1411–1415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannick EE, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase, nitrotyrosine, and apoptosis in Helicobacter pylori gastritis: effect of antibiotics and antioxidants. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3238–3243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahm KB, et al. Possibility of chemoprevention by the eradication of Helicobacter pylori: oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis in H. pylori infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1853–1857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felley CP, et al. Oxidative stress in gastric mucosa of asymptomatic humans infected with Helicobacter pylori: effect of bacterial eradication. Helicobacter. 2002;7:342–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2002.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakaguchi AA, et al. Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and peroxynitrite in Helicobacter pylori gastric ulcer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;27:781–789. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaturvedi R, et al. Polyamines impair immunity to Helicobacter pylori by inhibiting L-arginine uptake required for nitric oxide production. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1686–1698. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis ND, et al. Immune evasion by Helicobacter pylori is mediated by induction of macrophage arginase II. J. Immunol. 2011;186:3632–3641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Touati E, et al. Chronic Helicobacter pylori infections induce gastric mutations in mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1408–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsubara S, et al. Cloning of Mongolian gerbil cDNAs encoding inflammatory proteins, and their expression in glandular stomach during H. pylori infection. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:798–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elfvin A, et al. Gastric expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and myeloperoxidase in relation to nitrotyrosine in Helicobacter pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1013–1018. doi: 10.1080/00365520600633537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CW, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication prevents progression of gastric cancer in hypergastrinemic INS-GAS mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3540–3548. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barry DP, et al. Cationic amino acid transporter 2 enhances innate immunity during Helicobacter pylori infection. Plos One. 2011;6:e29046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez-Perez GI, et al. Activation of human THP-1 cells and rat bone marrow-derived macrophages by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:1183–1187. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1183-1187.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Assmann IA, et al. Role of virulence factors, cell components and adhesion in Helicobacter pylori-mediated iNOS induction in murine macrophages. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2001;30:133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JM, et al. Up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric epithelial cells: possible role of interferon-gamma in polarized nitric oxide secretion. Helicobacter. 2002;7:116–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1083-4389.2002.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho SO, et al. Involvement of Ras and AP-1 in Helicobacter pylori-induced expression of COX-2 and iNOS in gastric epithelial AGS cells. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010;55:988–996. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0828-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angrisano T, et al. Helicobacter pylori regulates iNOS promoter by histone modifications in human gastric epithelial cells. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012;201:249–257. doi: 10.1007/s00430-011-0227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perfetto B, et al. Interferon-gamma cooperates with Helicobacter pylori to induce iNOS-related apoptosis in AGS gastric adenocarcinoma cells. Res. Microbiol. 2004;155:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JM, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection activates NF-kappaB signaling pathway to induce iNOS and protect human gastric epithelial cells from apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G1171–1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00502.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uno K, et al. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 induced through TLR4 signaling initiated by Helicobacter pylori cooperatively amplifies iNOS induction in gastric epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1004–1012. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00096.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson KT, et al. Helicobacter pylori stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and activity in a murine macrophage cell line. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1524–1533. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuyama N, et al. Non-standard biological activities of lipopolysaccharide from Helicobacter pylori. J. Med. Microbiol. 2001;50:865–869. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-10-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie QW, et al. Cloning and characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase from mouse macrophages. Science. 1992;256:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1373522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gobert AP, et al. Helicobacter pylori arginase inhibits nitric oxide production by eukaryotic cells: a strategy for bacterial survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:13844–13849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241443798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gobert AP, et al. Cutting edge: urease release by Helicobacter pylori stimulates macrophage inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Immunol. 2002;168:6002–6006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz JT, Allen LA. Role of urease in megasome formation and Helicobacter pylori survival in macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;79:1214–1225. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0106030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyazawa M, et al. Suppressed apoptosis in the inflamed gastric mucosa of Helicobacter pylori-colonized iNOS-knockout mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:1621–1630. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obonyo M, et al. Interactions between inducible nitric oxide and other inflammatory mediators during Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2003;8:495–502. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirahashi M, et al. Induced nitric oxide synthetase and peroxiredoxin expression in intramucosal poorly differentiated gastric cancer of young patients. Pathol. Int. 2014;64:155–163. doi: 10.1111/pin.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nam KT, et al. Decreased Helicobacter pylori associated gastric carcinogenesis in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Gut. 2004;53:1250–1255. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.030684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tatemichi M, et al. Increased risk of intestinal type of gastric adenocarcinoma in Japanese women associated with long forms of CCTTT pentanucleotide repeat in the inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter. Cancer Lett. 2005;217:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaise M, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase gene promoter polymorphism is associated with increased gastric mRNA expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and increased risk of gastric carcinoma. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007;19:139–145. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000252637.11291.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma N, et al. Accumulation of 8-nitroguanine in human gastric epithelium induced by Helicobacter pylori infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;319:506–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katsurahara M, et al. Reactive nitrogen species mediate DNA damage in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. Helicobacter. 2009;14:552–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yermilov V, et al. Formation of 8-nitroguanine by the reaction of guanine with peroxynitrite in vitro. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2045–2050. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.9.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsuji S, et al. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 25 Suppl 1, S186-19. 1997 doi: 10.1097/00004836-199700001-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe S, et al. Helicobacter pylori induces apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells through inducible nitric oxide. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000;15:168–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gobert AP, et al. Helicobacter pylori induces macrophage apoptosis by activation of arginase II. J. Immunol. 2002;168:4692–4700. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chaturvedi R, et al. Induction of polyamine oxidase 1 by Helicobacter pylori causes macrophage apoptosis by hydrogen peroxide release and mitochondrial membrane depolarization. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:40161–40173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vareille M, et al. Nitric oxide inhibits Shiga-toxin synthesis by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:10199–10204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702589104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Branchu P, et al. NsrR, GadE, and GadX interplay in repressing expression of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 LEE pathogenicity island in response to nitric oxide. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003874. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D'Autreaux B, et al. A non-haem iron centre in the transcription factor NorR senses nitric oxide. Nature. 2005;437:769–772. doi: 10.1038/nature03953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gilberthorpe NJ, Poole RK. Nitric oxide homeostasis in Salmonella typhimurium: roles of respiratory nitrate reductase and flavohemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:11146–11154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bang IS, et al. Maintenance of nitric oxide and redox homeostasis by the Salmonella flavohemoglobin hmp. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:28039–28047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hung CL, et al. The CrdRS two-component system in Helicobacter pylori responds to nitrosative stress. Mol. Microbiol. 2015;97:1128–1141. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuwahara H, et al. Helicobacter pylori urease suppresses bactericidal activity of peroxynitrite via carbon dioxide production. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:4378–4383. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4378-4383.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lewis ND, et al. Arginase II restricts host defense to Helicobacter pylori by attenuating inducible nitric oxide synthase translation in macrophages. J. Immunol. 2010;184:2572–2582. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moyat M, et al. Role of inflammatory monocytes in vaccine-induced reduction of Helicobacter felis infection. Infect. Immun. 2015;83:4217–4228. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01026-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagata K, et al. Helicobacter pylori generates superoxide radicals and modulates nitric oxide metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14071–14073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qu W, et al. Identification of S-nitrosylation of proteins of Helicobacter pylori in response to nitric oxide stress. J. Microbiol. 2011;49:251–256. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-0262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bodenmiller DM, Spiro S. The yjeB (nsrR) gene of Escherichia coli encodes a nitric oxide-sensitive transcriptional regulator. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:874–881. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.874-881.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poole RK, et al. Nitric oxide, nitrite, and Fnr regulation of hmp (flavohemoglobin) gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5487–5492. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5487-5492.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Justino MC, et al. Helicobacter pylori has an unprecedented nitric oxide detoxifying system. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;17:1190–1200. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Justino MC, et al. FrxA is an S-nitrosoglutathione reductase enzyme that contributes to Helicobacter pylori pathogenicity. FEBS J. 2014;281:4495–4505. doi: 10.1111/febs.12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuhns LG, et al. Comparative roles of the two Helicobacter pylori thioredoxins in preventing macromolecule damage. Infect. Immun. 2015;83:2935–2943. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00232-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Comtois SL, et al. Role of the thioredoxin system and the thiol-peroxidases Tpx and Bcp in mediating resistance to oxidative and nitrosative stress in Helicobacter pylori. Microbiol. 2003;149:121–129. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McGee DJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori thioredoxin is an arginase chaperone and guardian against oxidative and nitrosative stresses. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:3290–3296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qu W, et al. Helicobacter pylori proteins response to nitric oxide stress. J. Microbiol. 2009;47:486–493. doi: 10.1007/s12275-008-0266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bryk R, et al. Peroxynitrite reductase activity of bacterial peroxiredoxins. Nature. 2000;407:211–215. doi: 10.1038/35025109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu J, Holmgren A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;66:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gobert AP, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 dysregulates macrophage polarization and the immune response to Helicobacter pylori. J. Immunol. 2014;193:3013–3022. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gobert AP, et al. Helicobacter pylori induces macrophage apoptosis by activation of arginase II. J. Immunol. 2002;168:4692–4700. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fandriks L, et al. Water extract of Helicobacter pylori inhibits duodenal mucosal alkaline secretion in anesthetized rats. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1570–1575. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.von Bothmer C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection inhibits antral mucosal nitric oxide production in humans. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;37:404–408. doi: 10.1080/003655202317316024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aydemir S, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication lowers serum asymmetric dimethylarginine levels. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:685903. doi: 10.1155/2010/685903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bussiere FI, et al. Spermine causes loss of innate immune response to Helicobacter pylori by inhibition of inducible nitric-oxide synthase translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:2409–2412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chaturvedi R, et al. L-arginine availability regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent host defense against Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:4305–4315. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00578-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barry DP, et al. Difluoromethylornithine is a novel inhibitor of Helicobacter pylori growth, CagA translocation, and interleukin-8 induction. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McGee DJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori rocF is required for arginase activity and acid protection in vitro but is not essential for colonization of mice or for urease activity. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:7314–7322. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7314-7322.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Falush D, et al. Recombination and mutation during long-term gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori: estimates of clock rates, recombination size, and minimal age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:15056–15061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251396098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cunningham MD, et al. Helicobacter pylori and Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharides are poorly transferred to recombinant soluble CD14. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:3601–3608. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3601-3608.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mueller D, et al. c-Src and c-Abl kinases control hierarchic phosphorylation and function of the CagA effector protein in Western and East Asian Helicobacter pylori strains. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:1553–1566. doi: 10.1172/JCI61143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Higashi H, et al. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Science. 2002;295:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1067147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Supajatura V, et al. Cutting edge: VacA, a vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori, directly activates mast cells for migration and production of proinflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2603–2607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]