Abstract

Introduction

Despite limitations in evidence, the current Clinical Practice Guideline advocates Motivational Interviewing for smokers not ready to quit. This study evaluated the efficacy of Motivational Interviewing (MI) for inducing cessation-related behaviors among smokers with low motivation to quit.

Design

Randomized clinical trial.

Setting/participants

Two-hundred fifty-five daily smokers reporting low desire to quit smoking were recruited from an urban community during 2010–2011 and randomly assigned to Motivational Interviewing, health education, or brief advice using a 2:2:1 allocation. Data were analyzed from 2012 to 2014.

Intervention

Four sessions of Motivational Interviewing utilized a patient-centered communication style that explored patients’ own reasons for change. Four sessions of health education provided education related to smoking cessation while excluding elements characteristic of Motivational Interviewing. A single session of brief advice consisted of brief, personalized advice to quit.

Main outcomes measures

Self-reported quit attempts, smoking abstinence (biochemically verified), use of cessation pharmacotherapies, motivation, and confidence to quit were assessed at baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-ups.

Results

Unexpectedly, no significant differences emerged between groups in the proportion who made a quit attempt by 6-month follow-up (Motivational Interviewing, 52.0%; health education, 60.8%; brief advice, 45.1%; p=0.157). Health education had significantly higher biochemically verified abstinence rates at 6 months (7.8%) than brief advice (0.0%) (8% difference, 95% CI=3%, 13%, p=0.003), with the Motivational Interviewing group falling in between (2.9% abstinent, 3% risk difference, 95% CI=0%, 6%, p=0.079). Both Motivational Interviewing and health education groups showed greater increases in cessation medication use, motivation, and confidence to quit relative to brief advice (all p<0.05), and health education showed greater increases in motivation relative to Motivational Interviewing (Cohen’s d=0.36, 95% CI=0.12, 0.60).

Conclusions

Although Motivational Interviewing was generally more efficacious than brief advice in inducing cessation behaviors, health education appeared the most efficacious. These results highlight the need to identify the contexts in which Motivational Interviewing may be most efficacious and question recommendations to use Motivational Interviewing rather than other less complex cessation induction interventions.

Introduction

In recent years, adult smoking rates have remained relatively stable.1 Unfortunately, about 80% of smokers have no immediate intention to quit.2, 3 Proactive cessation induction interventions that foster efforts to quit among unmotivated smokers could have profound public health impact even if the efficacy is small.

The Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence recommends the use of Motivational Interviewing (MI) with smokers who, after receiving advice to quit, express low motivation to quit.4 MI is a patient-centered style of communication designed to strengthen motivation and commitment to behavior change in a manner that avoids confrontation or persuasion.5 Several recent meta-analyses suggest that MI, which is now widespread in use, has modest positive effects on cessation when compared with lower-intensity interventions such as brief advice (BA).6–9 However, prior work has often failed to assess the quality and fidelity of MI implementation to establish that core MI components were delivered adequately.6–8 Studies have also typically compared MI with BA, and rarely against an equal-intensity alternative intervention.6–8 This is needed to ensure that observed effects are due to the active components of MI rather than differential duration of clinical contact. There is also evidence that MI may be more efficacious relative to other treatments with patients low in motivation to quit; however, studies have not always targeted these individuals.6, 10 Research is also needed that focuses on the efficacy of MI for inducing quit attempts7 and impacting theoretically important motivational constructs.6 Given the skill and extent of training needed to deliver MI,11 stronger evidence is needed to support its use.

This study addressed these limitations by examining the efficacy of MI relative to a matched intensity educational intervention (health education [HE]) and BA to quit for inducing quit attempts among smokers low in motivation to quit. The study compared MI with HE because HE is a practical alternative to MI that is clearly distinct in the approach to motivating behavior change. For example, in MI the emphasis is placed on facilitating patient exploration and expression of their own reasons for change rather than providing information the provider considers important to persuade the patient to change. According to MI principles, these methods should be more efficacious at overcoming patient ambivalence about change and should foster “internally” motivated behavior change.5 For these reasons, MI was expected to produce more quit attempts as well as greater smoking-cessation medication use, cessation motivation, and increased cessation relative to HE. MI was also compared with BA to examine its effect relative to minimal treatment and to compare findings with prior research.

Methods

Details of the study methods have been documented elsewhere.12 The IRB of the University of Missouri–Kansas City approved the study protocol.

Study Design

This study was a single-site, parallel-group RCT. Smokers low in desire to quit smoking were randomly assigned to one of three types of smoking–cessation induction therapies (MI, HE, or BA) with an imbalanced allocation (2:2:1). Blinding of the counselors was not possible. Participants were not given any information about the content distinctions between treatment groups and thus were blind to this aspect of the study. Baseline and follow-up measures were collected via computer.

Study Setting and Participants

From November 2010 to November 2011, smokers were recruited in a large Midwestern city with flyers, advertisements, and e-mail messages placed community-wide using newspapers, billboards, social media, university campuses, and healthcare provider offices. Advertising messages invited participation in a study for “smokers” or “smokers not quite ready to quit.” Smokers were prescreened by phone and then rescreened for final eligibility at baseline (Figure 1). Potential participants were told that the purpose of the study was to learn about how healthcare providers should talk to their patients about smoking. Smokers were told that although their smoking habits would be discussed during the study, they were not required to quit.

Figure 1. Flow of participants through the trial.

Reasons for being dropped from enrollment are not mutually exclusive. Values next to the number of sessions completed represent the cumulative number of participants who completed at least that many treatment sessions.

Eligibility criteria included:

age ≥18 years;

currently smoking one or more cigarette per day;

English speaking;

stable reachability;

no intentions of pregnancy for the next 6 months;

no current use of cessation medication;

no cessation plans in the next 7 days;

confirmed tobacco use using expired-air carbon monoxide ≥7 ppm13, 14 (not collected for the first 24 enrolled participants); and

being unmotivated to quit smoking operationalized as ≤6 on a self-report scale of: How motivated are you to quit smoking? (0, not at all; 10, extremely).3

The motivation criteria were designed to ensure participants were suitable for a motivational intervention and the motivational cut-point is consistent with meta-analytic evidence of greater efficacy of MI.6

General Procedures

A predetermined computer-generated randomization sequence was prepared by the study statistician and provided in sealed opaque envelopes. After research assistants enrolled participants and baseline measures were collected, research assistants opened envelopes to allocate participants to treatment group. Participants then received an in-person intervention session based on group assignment. Those in the MI and HE groups received one additional in-person session at Week 12 and two phone sessions at Weeks 6 and 18. Sessions were separated by 6 weeks to avoid excessively pressuring smokers to change. Scheduling was altered if a person set a quit date so that all remaining sessions were scheduled on the day after the selected quit day and then every week after that (25% of MI and HE participants), consistent with the U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline.4 Participants returned to complete follow-up assessments via computer at 3 and 6 months. Participants received compensation for each completed study component (up to $120 for BA and $150 for MI and HE).

To meet the standard of care, participants in all three groups who expressed any interest in quitting were offered a self-help guide and, for those who set a quit date, free pharmacotherapy (varenicline was recommended but nicotine patch and lozenge were also offered). Participants were not informed of the availability of free pharmacotherapy until they set a quit date to avoid providing an incentive to quit.

Brief Advice (Minimal Usual Care Comparison)

The single-session BA intervention lasted approximately 5 minutes and followed a semi-structured script based on the Clinical Practice Guideline.4 Counselors assessed smoking-related symptoms, provided clear and strong advice to quit referring to any patient-reported symptoms, and asked about interest in quitting and any planned quit date.

Health Education (Intensity-Matched Comparison)

The four-session HE intervention was based on the “5 R’s” (i.e., relevant risks of smoking, rewards of quitting, roadblocks to cessation, repetition at each visit) of the U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline but excluded elements characteristic of MI. To ensure HE was distinct from MI, counselors followed a script and presented information via a computer during in-person visits. The protocol included:

assessment of smoking and cessation history using a standardized set of questions;

education about the risks and costs of smoking according to the script;

education about the benefits of quitting according to the script;

education about potential solutions to the common obstacles to quitting; and

personalized advice and standardized assessment of intent to quit.

Counselors avoided engaging participants in conversation other than to ask if there were any questions about the provided information and at the conclusion to ask whether they wanted to make a plan to quit smoking. Counselors were also able to answer common questions or comments by patients with pre-scripted answers. For those wanting to quit, counselors used a guideline-based quit plan form that included changing environmental triggers, preparing for obstacles, self-rewarding, setting a quit date, and choosing medication. Counselors were trained to maintain an “advice-oriented” style of counseling during quit planning. Subsequent sessions reviewed progress with the quit plan and avoiding relapse.

Motivational Interviewing (Intervention)

The MI sessions were unscripted and counselors used the style (e.g., empathic, collaborative, and autonomy-supportive) and methods (i.e., open-ended questions, affirmations, and reflections) of MI.5 Counselors encouraged patient engagement in the conversation by exploring patient ambivalence regarding smoking cessation, developing discrepancy between the client’s goals/values (e.g., health) and current behaviors (i.e., smoking), and increasing “change talk” while avoiding arguing or disputing “sustain talk.” Provision of information was minimized and offered only when judged necessary. For participants who expressed an interest in quitting, the MI counselor worked to strengthen the commitment for change and used an MI style to complete the guideline-based quit plan and follow-up sessions as described above.

Interventionists and Intervention Fidelity

Counselors were three Master’s-level professionals experienced with delivering MI in randomized trials. Because psychotherapy research indicates that counselor effects can be stronger than treatment effects,15, 16 each counselor delivered all three treatments. This avoided confounding counselor and treatment effects. To prevent treatment contamination, the HE and BA arms were scripted and stringent measures were implemented to ensure fidelity. Training, practice, and supervision for each of the interventions continued until counselors met fidelity criteria for three consecutive sessions (training hours per counselor were 96 for MI and 28.5 for HE). Counselors then began counseling enrolled participants and received regular group supervision of a randomly selected recent audio recording from separate expert clinicians for each of the interventions (weekly for MI, every other week for HE, and monthly for BA). Study-specific rating scales were completed to verify fidelity. To verify treatment integrity, the duration of sessions was assessed and randomly selected 10% of regular sessions (i.e., excluding quit plans and follow-ups) for evaluation (38 MI and 37 HE), using the MI Treatment Integrity Code17 by an independent expert coding group blind to group assignment. The Code yields ratings of counselor adherence to MI including overall ratings of the session (e.g., expression of empathy) and behavior counts (e.g., frequency of open-ended questions).

Measures

Assessments were obtained at baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Baseline measures included socio-demographic details (Table 1), smoking characteristics, and nicotine dependence using the Severity of Dependence Scale.18 Race/ethnicity was assessed by patient self-report. The primary outcome was the self-report of any serious attempt to quit smoking for at least 24 hours during the previous 3 months and was collected at baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Cumulative occurrence of any quit attempt for the entire follow-up period was calculated by collapsing across 3- and 6-month assessments. Additionally, self-report 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence was collected at 3 and 6 months, and verified biochemically at 6 months using saliva cotinine.19 Use of any smoking-cessation medications since the last assessment was measured at 3 months and 6 months with a self-report checklist of various cessation pharmacotherapies. Motivation to quit smoking was assessed at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months by aggregating three self-report items: motivation to quit (0, not at all; 10, extremely), motivation to quit in the next 2 weeks (0, not at all; 10, extremely), and the Contemplation Ladder (0, no thought of quitting; 10, taking action to quit).3, 20 Similarly, confidence to quit smoking was assessed by aggregating two self-report items: confidence to quit and confidence to quit in the next 2 weeks (0, not at all; 10, extremely).21

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Group Assignment

| Characteristic | Motivational interviewing (n=102) | Health education (n=102) | Brief advice (n=51) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | |||

| Sex - Female | 47 (46) | 41 (40) | 22 (43) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 29 (28) | 30 (29) | 15 (29) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 68 (67) | 68 (67) | 31 (61) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (4) |

| Hispanic | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Monthly income, % | |||

| Less than $1000 | 58 (57) | 59 (58) | 30 (59) |

| $1000-$2000 | 20 (20) | 17 (17) | 11 (22) |

| Greater than $2000 | 11 (11) | 14 (14) | 5 (10) |

| Declined to answer | 13 (13) | 12 (12) | 5 (10) |

| Education, % | |||

| Less than high school | 18 (18) | 21 (21) | 10 (20) |

| High school or equivalent | 70 (69) | 63 (62) | 34 (67) |

| More than high school | 14 (14) | 18 (18) | 7 (14) |

| Married/In committed relationship | 17 (17) | 20 (20) | 9 (18) |

| Smokes 1st cigarette within 5 mins of waking | 48 (47) | 49 (48) | 31 (61) |

| Prior use of cessation medications | 18 (18) | 28 (28) | 10 (20) |

| Lives with other smokers | 52 (51) | 56 (55) | 28 (55) |

| At least 1 prior quit attempt | 65 (64) | 73 (72) | 34 (68) |

| Age in years (M, ±SD) | 45.0 ±11.7 | 46.7 ±10.2 | 45.5 ±10.5 |

| Cigarettes per day (M, ±SD) | 16.2 ±9.0 | 16.9 ±9.4 | 18.0 ±10.8 |

| Age of 1st cigarette (M, ±SD) | 16.5 ±4.1 | 15.8 ±4.7 | 16.9 ±6.8 |

| Severity of dependence scale a (M, ±SD) | 6.6 ±2.9 | 6.9 ±3.5 | 5.7 ±2.7 |

| Motivation to quit b (M, ±SD) | 1.9 ±1.9 | 1.8 ±1.5 | 1.9 ±1.9 |

| Confidence to quit c (M, ±SD) | 2.7 ±2.6 | 2.6 ±2.8 | 2.5 ±2.7 |

Note: No statistically significant differences between groups (all p>0.05).

Five item dependence scale 18 with a score ranging from 0 to 15.

On a scale of 0 to 10, based on mean of 3 items: Contemplation Ladder, “motivation to quit now”, and “motivation to quit in next 2 weeks.” 3, 20

On a scale of 0 to 10, based on 2 items: “confident to quit if wanted” and “confident to quit in next 2 weeks.” 21

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups on demographic, psychosocial, smoking characteristics, and fidelity ratings were examined using ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. To confirm treatment fidelity, MI sessions were expected to be scored significantly higher than HE sessions on all criteria except “direction” (i.e., maintains appropriate focus on target behavior). Analyses were based on an intent-to-treat approach where all randomized participants were included. Primary outcomes were examined using two distinct methods for handling missing data. The first method used a worst case scenario imputation strategy22 (WCS) and treated patients with missing follow-ups as smoking, or as not having made a quit attempt (WCS or missing=smoking). A second method used a maximum likelihood–based approach23 (ML) to accommodate missing data as missing at random (ML or missing=missing) and utilized all available information without patient exclusion or imputation. Analyses of secondary outcomes (e.g., motivation to quit) only utilized an approach where missing data were accommodated as missing (ML). Where possible, values for baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-up were included in the model. Effects of treatment group, time, and group by time interactions were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed modeling approach with a binomial distribution and logit link for binary measures and a normal distribution and identity link for continuous measures. In some cases, the parameter estimates were unstable owing to low cell counts (e.g., biochemically verified abstinence) and analyses using generalized estimating equations produced usable statistics. Planned comparisons between groups at follow-up time points utilized a Fisher least significant difference approach. Data were re-analyzed controlling for counselor effects. All analyses were conducted from 2012 to 2014 using SPSS, version 21. A priori power calculations indicated that a sample size of 255 with the 2:2:1 allocation (MI and HE, n=102; BA, n=51) would have an 80% power to detect a clinically meaningful difference of 25% in the proportion making a quit attempt between the MI and HE groups and a 40% difference between the MI and BA groups, assuming an estimated attrition of 25%, and α=0.05.12

Results

Mean age for the 255 participants was 45.8 (SD=10.9) years with 43.1% being female (Table 1). Sources of recruitment for those enrolled were word of mouth (67.5%), newspaper advertisement (18.8%), clinic fliers (5.9%), campus fliers (4.3%), or other methods (3.5%). Most participants were non-white (68.2%) with lower income (76.4% <$2000 per month). Average number of years smoked was 29.5 (SD=11.8) years and average cigarettes smoked per day were 17.1 (SD=8.9). Average motivation to quit smoking was 1.9 (SD=1.7). Analyses revealed no significant baseline differences between treatment groups. Logistic regression analyses revealed no significant differences in attrition rates between the groups (Figure 1), with overall completion rates of 94.1% (n=240) at Month 3 and 89.4% (n=228) at Month 6. At least one follow-up assessment was available for 95.1% of MI (n=97), 95.1% of HE (n=97), and 94.1% of BA (n=48) patients.

As predicted, MI sessions were scored significantly higher than HE on all global ratings except for direction (all p<0.001) and on all behavior counts. Effect sizes were large with standardized mean differences (Cohen’s d) ranging from 1.5 to 2.3 (Table 2). In addition, average session duration did not significantly differ (p=0.413) between MI (mean, 24.2 minutes/session; SD=7.1) and HE (mean, 23.7 minutes/session; SD=7.4).

Table 2.

Assessment of Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity a

| Measure | Motivational Interviewing (n=38) | Health education (n=37) | Between group standardized mean Difference (95% CI)c | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Mean ±SD | Aboveb criterion | Mean ±SD | Aboveb criterion | |||

| Global ratings (1–5): | ||||||

| Empathy | 4.5 ±0.6 | 95% | 2.3 ±1.2 | 24% | 2.3 (1.8 to 2.8) | <0.001 |

| Direction | 4.9 ±0.4 | 97% | 4.7 ±0.8 | 95% | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.8) | 0.17 |

| Collaboration | 4.2 ±0.9 | 79% | 2.1 ±1.2 | 14% | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.5) | <0.001 |

| Evocation | 4.4 ±0.7 | 92% | 2.3 ±1.1 | 19% | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.7) | <0.001 |

| Autonomy support | 4.3 ±0.8 | 87% | 2.8 ±1.2 | 27% | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | <0.001 |

| Additional metrics | ||||||

| Giving information (counts) | 3.9 ±4.8 | n.a | 12.8 ±9.5 | n.a. | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.7) | <0.001 |

| Reflections: Questions (ratio of counts) | 3.1 ±2.4 | 92% | 0.2 ±0.3 | 5% | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.1) | <0.001 |

| Open-ended questions (%) | 66.0 ±27.6 | 76% | 10.5 ±11.0 | 3% | 2.6 (2.2 to 3.1) | <0.001 |

| Complex reflections (%) | 53.9 ±16.3 | 82% | 19.6 ±27.6 | 24% | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | <0.001 |

| MI adherent (%) | 79.4 ±37.9 | 71% | 30.3 ±42.6 | 22% | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.7) | <0.001 |

| MI adherent behavior counts | 2.3 ±1.7 | n.a. | 0.8 ±1.3 | n.a. | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.5) | <0.001 |

| MI non-adherent behavior counts | 0.2 ±0.7 | n.a. | 1.5 ±3.0 | n.a. | 0.6 (0.1 to 1.1) | <0.001 |

Note: Boldface indicates significant between group difference, p<0.05.

Audio recordings of 75 treatment sessions were randomly selected and scored using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Coding17 by independent expert coders, who were blind to group assignment and study hypotheses.

Criteria used: global ratings score ≥4 (1–5 scale); giving information counts - no established criterion; reflection-question ratio = (#reflections / #questions) ≥1.0; % open-ended questions = 100*(#open-ended questions / #total questions) ≥50; %complex reflections=100* (#complex reflections / #total reflections) ≥40%; %MI adherent=100*(# MI adherent behaviors / #MI adherent + #MI non-adherent) = 100%

Standardized mean difference, or Cohen’s d, calculated by (mean MI - mean HE) / pooled standard deviation.

During the study, a total of 138 of the 255 enrolled participants (54%) reported making at least one serious 24-hour quit attempt. Table 3 presents results for the WCS (missing=smoking) analyses and the ML (missing=missing) analyses. Both analyses failed to reveal any significant differences between the three treatment groups in the proportion making any quit attempt (MI, 52.0%; HE, 60.8%; BA, 45.1%; χ2=3.70, p=0.157 for WCS), although the difference between HE and BA approached significance for the WCS analyses (risk difference [RD]=16%, 95% CI= −1, 32, p=0.064). Analyses of 90-day prevalence rates for quit attempts at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months revealed a similar pattern of null findings, with no effects of treatment group (WCS, p=0.809) or group by time interactions (WCS, p=0.564). Nevertheless, there was a significant main effect of time (p<0.001). Across all groups, 90-day quit attempt rates increased from baseline by 24% (WCS, 95% CI=18, 30) at 3-month follow-up and 37% (WCS, 95% CI=30, 44) at 6-month follow-up.

Table 3.

Smoking Cessation Outcomes by Treatment Group

| Motivational Interviewing | Health education | Brief advice | Effects | Pairwise absolute risk differences (95% C.I.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure and follow-up period | % | % | % | p-value a | MI - BA | MI - HE | HE - BA | |

| Quit attempt: cumulativeb | ||||||||

| Missing=smoking c | 52.0 | 60.8 | 45.1 | 0.157 | 7 ( −1 to 24) | −9 (−22 to 5) | 16 (−1 to 32) | |

| Missing=missing d | 57.6 | 65.3 | 52.3 | 0.297 | 5 (−13 to 23) | −8 (−22 to 6) | 13 (−5 to 31) | |

| Quit attempt: last 90 days | ||||||||

| 3-months | Missing=smoking | 31.4 | 39.2 | 31.4 | 0 (−16 to 16) | −8 (−21 to 5) | 8 ( −8 to 24) | |

| Missing=missing | 33.2 | 41.5 | 34.5 | 1 (−18 to 15) | −8 (−22 to 5) | 7 (−10 to 24) | ||

| 6-months | Missing=smoking | 45.1 | 52.9 | 43.1 | 0.564 | 2 (−15 to 19) | −8 (−22 to 6) | 10 ( −7 to 27) |

| Missing=missing | 51.1 | 57.2 | 49.1 | 0.562 | 2 (−16 to 20) | −6 (−21 to 8) | 8 (−10 to 26) | |

| Abstinence: self-report 7-day | ||||||||

| 3-months | Missing=smoking | 4.9 | 7.8 | 0.0 | 5 ( 1 to 9) | −3 (−10 to 4) | 8 (3 to 13) | |

| Missing=missing | 5.2 | 8.6 | 0.0 | 5 ( 1 to 10) | −4 (−11 to 4) | 9 (3 to 14) | ||

| 6-months | Missing=smoking | 5.9 | 14.7 | 3.9 | 0.001 | 2 (−5 to 9) | −9 (−17 to −1) | 11 (2 to 20) |

| Missing=missing | 7.0 | 15.8 | 4.5 | 0.001 | 3 (−6 to 11) | −9 (−18 to 1) | 11 (2 to 21) | |

| Abstinence: verified at 6-month e | ||||||||

| Missing=smoking | 2.9 | 7.8 | 0.0 | 0.001 | 3 (0 to 6) | −5 (−11 to 1) | 8 (3 to 13) | |

| Missing=missing | 3.4 | 8.8 | 0.0 | 0.003 | 3 (0 to 7) | −5 (−12 to 2) | 9 (3 to 15) | |

| Cessation medication use f | ||||||||

| 3-months | Missing= no use | 6.9 | 13.7 | 9.8 | −3 (−1 to 7) | −8 (−16 to 1) | 4 (−1 to 15) | |

| Missing=missing | 7.2 | 14.8 | 10.5 | −3 (−2 to 7) | −8 (−17 to 1) | 4 (−7 to 16) | ||

| 6-months | Missing=no use | 24.5 | 31.4 | 9.8 | 0.034 | 15 (3 to 26) | −7 (−19 to 5) | 22 ( 9 to 34) |

| Missing=missing | 28.2 | 34.4 | 10.9 | 0.030 | 17 (4 to 30) | −6 (−20 to 7) | 24 (10 to 37) | |

Note: Boldface indicates pairwise risk difference significant, p<0.05.

Presented is the p-value for the overall test of Treatment Group, or Treatment Group X Time Interaction where applicable.

Self-report of any attempt to quit smoking for at least 24 hours during entire study follow-up (6 months).

Patients with missing data are treated as smoking; n=102, 102, 51 for MI, HE, & BA respectively.

Patients with missing data are accommodated as missing; at 3-month n=97, 96, 47 respectively; at 6-month n=90, 94, 44 respectively.

Biochemical verification of tobacco abstinence using saliva cotinine of 15ng/ml or less; 1 MI and 3 HE patients were missing cotinine due to lab error.

Aggregation of a self-report check list asking about various cessation medications.

Analyses of point-prevalence self-report 7-day smoking abstinence at 3- and 6-month follow-ups revealed a significant group by time interaction for both the WCS and ML analyses (p<0.001). At the 3-month assessment, both MI and HE groups reported significantly greater abstinence rates than the BA group (WCS, 5% and 8% vs 0%, all p<0.05). At the 6-month assessment, the HE group reported significantly greater abstinence rates than BA (WCS, 15% vs 4%, RD=11%, 95% CI=2, 20, p=0.016), and greater rates than MI (WCS, 15% vs 6%, RD=9%, 95% CI=1, 17, p=0.037). At 6 months, the MI group no longer differed significantly different from BA (RD=2%, 95% CI= −5, 9, p=0.584). In both WCS and ML analyses of biochemically verified abstinence rates at 6-months, the HE group showed better outcomes than BA (WCS, 7.8% vs 0%, RD=8%, 95% CI=3, 13, p=0.003). By contrast, the improved outcome of MI versus BA (2.9% vs 0%) only approached significance (WCS, RD=3%, 95% CI=0, 6, p=0.079).

In both WCS and ML analyses, the use of cessation pharmacotherapies through the 3- and 6-month follow-ups showed a significant group by time interaction (WCS, p=0.034). By the 6-month follow-up, a greater proportion of MI and HE participants (25% and 31% WCS, respectively) reported using cessation medications than BA participants (10%; MI, RD=15%, 95% CI=3, 26, p=0.014; HE, RD=22%, 95% CI=9, 34, p<0.001). There was no significant difference between MI and HE (WCS, p=0.274). Appendix Table 1 lists medication choices.

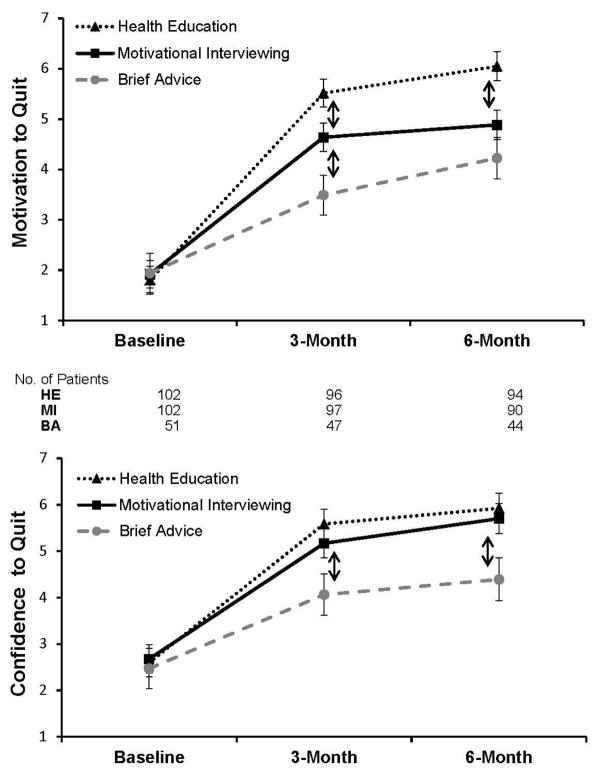

For motivation to quit, there was a significant group by time interaction (p<0.001, Figure 2). At 3 months, the MI participants reported greater motivation to quit compared with BA (mean difference=1.1, 95% CI=0.2, 2, p=0.019). In addition, at 3 months, the HE group reported greater motivation to quit than both the MI and BA groups (HE–BA difference=2.0, 95% CI=1.1, 3.0, p<0.001; HE–MI difference=0.9, 95% CI=0.1, 1.7, p=0.027). At 6 months, only HE participants reported greater motivation to quit relative to both MI and BA (HE–BA difference=1.8, 95% CI=0.8, 2.8, p<0.001; HE–MI difference=1.2, 95% CI=0.4, 2.0, p=0.004). The standardized mean difference between HE–MI was 0.36 (95% CI=0.12, 0.60). For confidence to quit smoking, the group by time interaction only approached significance (p=0.097), but there was a significant effect of group (p=0.047) and time (p<0.001). At 3 months, both MI and HE participants reported significantly greater confidence to quit relative to BA (MI–BA difference=1.1, 95% CI=0.03, 2.2, p=0.044; HE–BA difference=1.5, 95% CI=0.4, 2.6, p=0.006). The same was true for 6-month results (MI–BA difference=1.3, 95% CI=0.2, 2.4, p=0.020; HE–BA difference=1.5, 95% CI=0.4, 2.6, p=0.006). The pattern of outcome results across all measures was unaffected after controlling for counselor.

Figure 2. Effects of Treatment Group on Motivation and Confidence to Quit Smoking.

Means ± SE (on 0–10 scale) at baseline, 3-month, and 6-month follow-up. Motivation to quit based on mean of 3 items: Contemplation Ladder, “motivation to quit now”, and “motivation to quit in next 2 weeks”.3,20 Confidence to quit based on mean of 2 items: “confident to quit if wanted” and “confident to quit in next 2 weeks”.21 Patients with missing data are accommodated as missing in mixed modeling analyses. The number of patients is listed for each time period. Note: Arrows (↕) denote a significant difference (p<0.05) between the group above versus the group below.

Discussion

This study rigorously evaluated the efficacy of MI versus an intensity-matched comparison therapy (HE) to promote quit attempts among smokers with low motivation to quit smoking. Treatment integrity analyses suggested that MI was delivered with fidelity and that HE did not include core components of MI. Surprisingly, all three interventions were efficacious at increasing quit attempts and the efficacy of MI was less than expected. Relative to HE, MI either resulted in significantly poorer performance or failed to show any significant differences across measures of cessation activity.

Although unanticipated, these findings are consistent with a study that found no difference in cessation induction outcomes between a brief single session of MI and “prescriptive advice.”24 All groups in the present study showed significant increases in quit attempts relative to baseline, suggesting that various types and intensities of well-delivered interventions may prompt a substantial proportion of even low motivated smokers to attempt cessation. Results also suggest that more-intensive interventions will yield even greater cessation activity.

The HE intervention was clearly efficacious in this sample of smokers. Relative to BA, HE resulted in greater biochemically verified abstinence, use of cessation aids, and self-reported motivation and confidence to quit. HE outperformed MI on self-reported abstinence and motivation to quit at 6 months. The HE treatment delivered components of practice guidelines (e.g., the 5 R’s) in a way that minimized components central to MI (e.g., empathy, collaboration, fostering change talk). A similar 5 R treatment showed comparable effects in a prior cessation induction study for unmotivated smokers,25 suggesting that the 5 R’s can be efficacious without the MI components.

Although MI was not more efficacious than HE, MI did result in significantly greater cessation activity relative to the BA usual care control. In particular, MI resulted in significantly greater self-reported abstinence at 3 months, increased use of smoking-cessation pharmacotherapies throughout the 6-month follow-up, increased motivation to quit at 3 months, and increased confidence to quit at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. These beneficial effects of MI are consistent with several recent meta-analyses documenting the efficacy of MI in smoking cessation.6, 7, 26

The key question raised by the results is why HE appeared more efficacious than MI, under conditions that should have favored MI. MI is thought to be superior for individuals who are unmotivated to change behavior and was evaluated by investigators who are proponents of MI, employing adequately trained counselors and using measures to verify implementation. One explanation for this finding is that HE may have been a better match than MI for this sample that was predominantly African American and low in education level. For these individuals, the detailed health information may have been particularly informative and the directive style of HE may have been preferred. This is consistent with a national population-based survey that assessed public preferences regarding participation in clinical decision making that revealed African Americans had a significantly greater preference for leaving decisions to their doctor27 and a study of communication style preferences of rural African American women with Type 2 diabetes that found MI to be perceived as too patient centered.9, 28 One meta-analysis of MI interventions also found that having a higher proportion of African American participants was negatively associated with outcomes.9

An alternative explanation for the present study findings is that MI’s effects are predominantly non-specific (i.e., variables that are common across all counseling approaches). As expected, there were very large, theoretically important differences between the MI versus HE sessions in the presence of MI consistent counselor behaviors. Nevertheless, similarities in the counseling such as the use of quit plans when smokers expressed interest in quitting may have been more important than these differences. This is consistent with psychotherapy research, which generally fails to show the superiority of a particular type of therapy when compared with an alternative active treatment.29 Prior research supporting the efficacy of MI relative to BA could therefore be due simply to the greater duration of attention. It is also possible that HE and MI achieve their effects through different pathways (e.g., providing information that increases health concerns versus eliciting patient “change talk”).

Limitations

Limitations of the study include the use of a primary outcome measure based on self-report and the lack of power to detect smaller differences. However, the confluence of findings across all the measures in this study, including biochemically verified cessation, strongly supports the validity of the findings. Results may not generalize to all unmotivated smokers because those willing to enroll in a clinical trial may be more motivated than the present motivation assessments indicate. There is also a lack of consensus in the field regarding how best to conceptualize and operationalize motivation (e.g., desire to quit, readiness to quit according to stages of change, intention to quit).3 However, the study measures are well validated and are consistent with measures used in prior studies that indicated MI may be more efficacious for less motivated smokers.6 Findings should also not be interpreted to suggest brief MI would not outperform brief HE or that any health education would be equivalent or superior to MI. The intensity and quality used likely differs from usual primary care practice.30 For example, the counselors did not confront, shame, or argue with patients during delivery of HE, which might differ from what occurs in real-world delivery. Results should also be generalized cautiously beyond the population of lower-SES African Americans that were predominant in this study.

Conclusions

The MI intervention was more efficacious at inducing cessation-related outcomes than BA. However, HE appeared to be more efficacious than MI in this population and setting. Given the need for specialized training to deliver MI,31 these results question the necessity of the Clinical Treatment Guideline recommendation to use MI to induce quit attempts, particularly with low-income African Americans. Further research is needed to understand the contexts in which MI can best support tobacco cessation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathrene Conway, Mandy Seley, and Niaman Nazir for their administrative support. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or Pfizer. This study was supported by a grant (R01 CA133068) from NIH, National Cancer Institute. Pfizer provided varenicline (Chantix®) through Investigator-Initiated Research Support (No. WS759405).

Dr. Catley had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Catley, Harris, Goggin, Richter, Williams, Patten, Resnicow, and Ellerbeck. Acquisition of data: Catley, Williams, Bradley-Ewing, Lee, and Moreno. Drafting of manuscript: Catley and Grobe. Critical revision for important intellectual content: Goggin, Harris, Richter, Williams, Patten, Resnicow, Ellerbeck, Moreno, and Lee. Statistical analysis: Catley, Williams, and Grobe. Obtaining funding: Catley. Administrative, technical, or material support: Bradley-Ewing and Ellerbeck. Study Supervision: Catley, Goggin, Richter, and Bradley-Ewing.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01188018. October 2010. The study protocol was approved by the IRB of the University of Missouri–Kansas City (#0978).

Delwyn Catley reports grants from NIH, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and the National Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Foundation and non-financial support from Pfizer during the conduct of the study; Delwyn Catley occasionally received fees for providing Motivational Interviewing training. Kathy Goggin reports grants from NIH, PCORI and the National MS Foundation and consultant fees for providing Motivational Interviewing training. Karen Williams reports personal fees from Proctor and Gamble (P&G) and from P&G Global Advisory Committee, during the conduct of the study but outside of the submitted work. Ken Resnicow occasionally conducts Motivational Interviewing training and reports personal fees from University of Missouri–Kansas City during the conduct of the study. Edward Ellerbeck reports grants from NIH. James Grobe reports research consulting fees from the University of Texas-Southwestern & Texas Women’s University unrelated to the study. No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.CDC. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2005–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(2):29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velicer WF, Fava JL, Prochaska JO, Abrams DB, Emmons KM, Pierce JP. Distribution of smokers by stage in three representative samples. Prev Med. 1995;24(4):401–411. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1065. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1995.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herzog TA, Blagg CO. Are most precontemplators contemplating smoking cessation? Assessing the validity of the stages of change. Health Psychol. 2007;26(2):222–231. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: DHHS. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(6):868–884. doi: 10.1037/a0021498. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0021498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai DT, Cahill K, Qin Y, Tang JL. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD006936. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd006936.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Heckman CJ, Egleston BL, Hofmann MT. Efficacy of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2010;19(5):410–416. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.033175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2009.033175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A Meta-Analysis of Motivational Interviewing: Twenty-Five Years of Empirical Studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20(2):137–160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049731509347850. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahluwalia JS, Okuyemi K, Nollen N, et al. The effects of nicotine gum and counseling among African American light smokers: a 2 x 2 factorial design. Addiction. 2006;101(6):883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01461.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catley D, Harris KJ, Goggin K, et al. Motivational Interviewing for encouraging quit attempts among unmotivated smokers: study protocol of a randomized, controlled, efficacy trial. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:456. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedfont Scientific, Bedfont ScientificBedfont Scientifics. piCO+ Smokerlyzer.

- 14.Pearce MS, Hayes L. Self-reported smoking status and exhaled carbon monoxide: results from two population-based epidemiologic studies in the North of England. Chest. 2005;128(3):1233–1238. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.128.3.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D, Wampold BE, Bolt DM. Therapist effects in psychotherapy: A random-effects modeling of the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program data. Psychother Res. 2006;16(2):161–172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10503300500264911. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutz W, Leon SC, Martinovich Z, Lyons JS, Stiles WB. Therapist Effects in Outpatient Psychotherapy: A Three-Level Growth Curve Approach. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54(1):32–39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grassi MC, Ferketich AK, Enea D, Culasso F, Nencini P. Validity of the Italian version of the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) for nicotine dependence in smokers intending to quit. Psychol Rep. 2014;114(1):1–13. doi: 10.2466/18.15.PR0.114k16w7. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/18.15.PR0.114k16w7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooke F, Bullen C, Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Chen MH, Walker N. Diagnostic accuracy of NicAlert cotinine test strips in saliva for verifying smoking status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(4):607–612. doi: 10.1080/14622200801978680. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200801978680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10(5):360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boardman T, Catley D, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia JS. Self-efficacy and motivation to quit during participation in a smoking cessation program. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(4):266–272. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100(3):299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallgren K, Witkiewitz K. Missing Data in Alcohol Clinical Trials: A comparison of methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2013. 2013;37(12):2152–2160. doi: 10.1111/acer.12205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acer.12205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis MF, Shapiro D, Windsor R, et al. Motivational interviewing versus prescriptive advice for smokers who are not ready to quit. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(1):129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpenter MJ, Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Callas PW. Both smoking reduction with nicotine replacement therapy and motivational advice increase future cessation among smokers unmotivated to quit. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(3):371–381. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, et al. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller ST, Marolen KN, Beech BM. Perceptions of physical activity and motivational interviewing among rural African-American women with type 2 diabetes. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.09.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luborsky L, Rosenthal R, Diguer L, et al. The Dodo Bird Verdict Is Alive and Well—Mostly. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:2–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/9.1.2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Champassak SL, Goggin K, Finocchario-Kessler S, et al. A qualitative assessment of provider perspectives on smoking cessation counselling. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(3):281–287. doi: 10.1111/jep.12124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jep.12124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller WR, Mount KA. A Small Study of Training in Motivational Interviewing: Does One Workshop Change Clinician and Client Behavior? Behav Cogn Psychother. 2001;29:457–471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1352465801004064. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.