Abstract

Objective

This study reports on the association between religious beliefs and behaviors and the change in both general and religious social support using two waves of data from a national sample of African Americans.

Design

The Religion and Health in African Americans (RHIAA) study is a longitudinal telephone survey designed to examine relationships between various aspects of religious involvement and psychosocial factors over time.

Participants

RHIAA participants were 3,173 African American men (1,281) and women (1,892). A total of 1,251 men (456) and women (795) participated in wave 2 of data collection.

Results

Baseline religious behaviors were associated with increased overall religious social support from baseline to wave 2 (p<.001) and with increased religious social support from baseline to wave 2 in each of the following religious social support subscales: emotional support received (p<.001), emotional support provided (p<.001), negative interaction (p<.001), and anticipated support (p<.001). Religious beliefs did not predict change in any type of support, and neither beliefs nor behaviors predicted change in general social support.

Conclusions

African Americans who are active in faith communities showed increases in all types of religious social support, even the negative aspects, over a relatively modest longitudinal study period. This illustrates the strength of the church as a social network and the role that it plays in people’s lives.

Keywords: Religious Involvement, Social Support, Longitudinal, Survey Research, African American

Introduction

Religious involvement, defined as engagement in an organized system of religious beliefs, practices, rituals and symbols (Thoresen 1998), is particularly strong in many African American communities (Lincoln and Mamiya 1990), and the connection between religious involvement and health beliefs and behaviors among African Americans is well-documented (see Ellison and Hummer 2010; Koenig, King, and Carson 2012 for reviews). Several studies have examined how religious behaviors, such as attending church services, praying, reading scriptures, or meditating, are important factors in shaping health-related outcomes among African Americans (Biggar et al.1995; Engle, Fox-Hill, and Graney 1998; George, Ellison, and Larson 2002; Pargament 1997). Furthermore, there have been several studies that examine the role of religious beliefs as a potential barrier to healthcare-seeking behaviors among African Americans who express that prayer or divine intervention alone will address their illness and fail to seek out a medical professional (Dupree 2000; Hauser et al. 1997; Klonoff and Landrine 1996; Mathews, Lannin, and Mitchell 1994; Pargament 1997; Waters 2001; Wilson-Ford 1992). These findings highlight the significant relationship between religion and health among African Americans, and the importance of examining multiple dimensions of religious involvement.

Religious Social Support

A well-recognized reason why religious involvement is suggested to influence health is through the social support mechanisms provided by the church community (Cagle et al. 2002; Engle, Fox-Hill, and Graney 1998; Ferraro and Koch 1994; Holt et al. 2014; King and Bushwick, 1994; Pirutinsky et al. 2011). Some social support mechanisms include companionship, confiding relationships, positive feedback/reinforcement, and engaging in informal exchanges of tangible assistance and emotional support (Ellison and Hummer 2010). Social support is included in many models of the ‘religion-health connection’ (Robinson and Nussbaum 2004; Holt et al. 2013; Lincoln and Mamiya 1990; George et al. 2002; Ellison et al.1997; Musick, Koenig, Hays, and Cohen 1998; Musick, Blazer, and Hays 2000; Ellison and Hummer 2010; Kanu, Baker, and Brownson 2008; Kendler et al. 2003; Krause 2002; Krause 2006). In a mediational analysis of a national sample of African Americans, belonging and tangible aspects of social support were found to mediate the relationship between religious behaviors and physical functioning as well as depressive symptoms (Holt et al. 2014). In a sample of Jewish Americans, the relationship between physical health and depression was moderated by intrinsic religiosity and this effect was mediated by social support among non-Orthodox Jews but not among Orthodox Jews (Pirutinsky et al. 2011).

Specifically within the church however, the added ‘religious support’ mechanisms such as attending formal congregation programs, seeking clergy support, advice and counseling, and receiving encouragement to adapt and apply teachings of faith into daily life may provide a unique health benefit to congregation members (Debnam et al. 2012; Ellison and George 1994; Ferraro and Koch 1994; Holt et al. 2012; Krause 2003; Krause and Wulff 2005; Phillips and Sowell 2000). For example, it was reported that religious social support was predictive of a number of health-related behaviors among African Americans, above and beyond general social support (Debnam et al. 2012).

The literature often refers to social support networks within the church as ‘spiritual support’, ‘faith-based support’, or ‘religious support’ (Ellison and Hummer 2010). A 2006 longitudinal study using nationwide data from the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. found that African American congregations reported social support within the church as having an influence on individual health, such as in mitigating the harmful effects of financial stressors on physical health (Ellison et al. 2008). Several studies support evidence that emotional religious support may be a mediator in the relationship between religious behaviors and both emotional functioning and depressive symptoms (George et al. 2002; Holt et al. 2013; Holt et al. 2012; Jang and Johnson 2004; Jarvis and Northcott 1987; Nooney and Woodrum 2002; Prado et al. 2004; Sternthal, Williams, Musick, and Buck 2010).

The Present Study

The present study was designed to determine whether religious beliefs and behaviors were associated with change in religious social support over time. We also included analysis of general social support over time for comparison, to determine whether this relationship was unique to religious social support or also applied to support provided by general or secular sources. We anticipated that religious involvement, and in particular religious behaviors, would be associated with increases in religious social support over time. We expected similar relationships but of a lesser magnitude for general social support. Previous research has examined the role of religious social support as a predictor of health-related outcomes and as a mediator in the religion-and-health connection, however these have been largely cross sectional studies. Examining these relationships over time provides more sophisticated insights as to the role that religious communities play in people’s lives, specifically with regard to a support function, and provides greater confidence in mediational models involving support.

Methods

The current analysis used data from the Religion and Health in African Americans, or ‘RHIAA’ study, a national longitudinal cohort of healthy African American men and women (Holt et al. 2015). The RHIAA study was designed to explain relationships between religious involvement and psychosocial and health-related factors over time (e.g., health behaviors, physical/emotional functioning). The study had an overall response rate of 21%.

Wave 2 data collection occurred approximately 2.5 years after the baseline data collection. Retention strategies used in the study were consistent with recommendations from Hunt and White (Holt et al. 2015). Because the RHIAA study was not originally designed for participant re-contact, the retention rate from baseline to wave 2 was roughly 39% (i.e. of the 3,173 participants who participated at baseline, 1,251 were retained) (Holt et al. 2015). Higher retention was found among participants who were older and female. After adjusting for age and gender, participants who were retained tended to be more educated, single, and in better health status than those not retained. Findings from our adjusted analyses showed no difference in religious involvement (Holt et al. 2015).

RHIAA participants (N=3,173) completed a 1-hour telephone interview. An external data collection subcontractor, Opinion America, recruited the study sample. The RHIAA data collection and retention methods are reported in detail elsewhere (Holt et al. 2010; Holt et al. 2015). A professional sampling firm used probability-based methods to develop a list of households from public data such as motor vehicle records from all 50 United States. Experienced interviewers called telephone numbers from the call list, and asked to speak to an adult who lived at the household being contacted. Interviewers introduced the project and if the contact expressed interest, they completed a brief eligibility screener. Eligible participants were those who self-identified as being African American and age 21 or older. Interviewers read participants an informed consent script and documented verbal assent. Upon completion of the interview, study staff mailed participants a $25 store gift card.

Measures

Religious involvement

Religious involvement was assessed using an established Religiosity Scale previously validated with African Americans (Lukwago et al. 2001; Roth et al. 2012). This 9-item instrument includes religious beliefs (e.g., ‘I have a close personal relationship with God.’) and behaviors (e.g., church service attendance; ‘I often read religious books, magazines, or pamphlets.’). Items use a 5-point Likert-type format (strongly disagree…strongly agree), with the exception of two religious service attendance items assessed in 3-point format (0; 1–3; 4+). Scores range from 4–20 for beliefs and 5–21 for behaviors, with higher scores reflecting greater religious involvement. Previous studies have indicated excellent internal consistency reliability for this instrument (α = .85 for religious beliefs; α = .79 for religious behaviors).

Religious social support

Religious social support was assessed with an instrument from the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality for Health Research (Fetzer Institute, National Institute on Aging Working Group 1999). It measures social support specific to a faith community. The instrument assesses emotional support received (e.g. ‘How often do the people in your congregation listen to you talk about your private problems and concerns?’), emotional support provided (‘How often do you make the people in your congregation feel loved and cared for?’), anticipated support (e.g. ‘If you were ill how much would the people in your congregation be willing to help out?’), and negative interaction or negative congregational support (e.g. ‘How often do the people in your congregation make too many demands on you?’). Items use a 4-point Likert-type format from never to very often for emotional support and negative interaction and none to a great deal for anticipated support. Higher scores showed higher levels of support. Internal consistency reliability was acceptable in previous studies given the brevity of the instrument (α = .83 for overall scale; .61, .76, .64, .89 for subscales, respectively).

Social support

The Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-12) assessed general social support (Cohen 2009). This 12-item instrument includes appraisal (e.g., ‘I feel there is someone I can share my most private worries and fears with.’), belonging (e.g., ‘If I wanted to have lunch with someone, I could easily find someone to join me.’), and tangible (e.g., ‘If I were sick, I could easily find someone to help me with my daily chores.’) support, using a 4-point Likert-type scale (definitely false…definitely true). Higher scores reflect greater support. Internal reliability varied from .75 – .90 in four previous studies but was generally above .80 (Cohen 2009). Scores were related to marital adjustment, social network diversity, and social network size, as well as affective outcomes (ps < .05). Previous studies have shown adequate internal reliability for this instrument (α = .89 overall scale; α = .84, .75, .75 for subscales, respectively).

Demographics

A standard demographic module was used to document participant characteristics including age, gender, relationship status, educational attainment, work status, and household income.

Statistical Design and Analysis

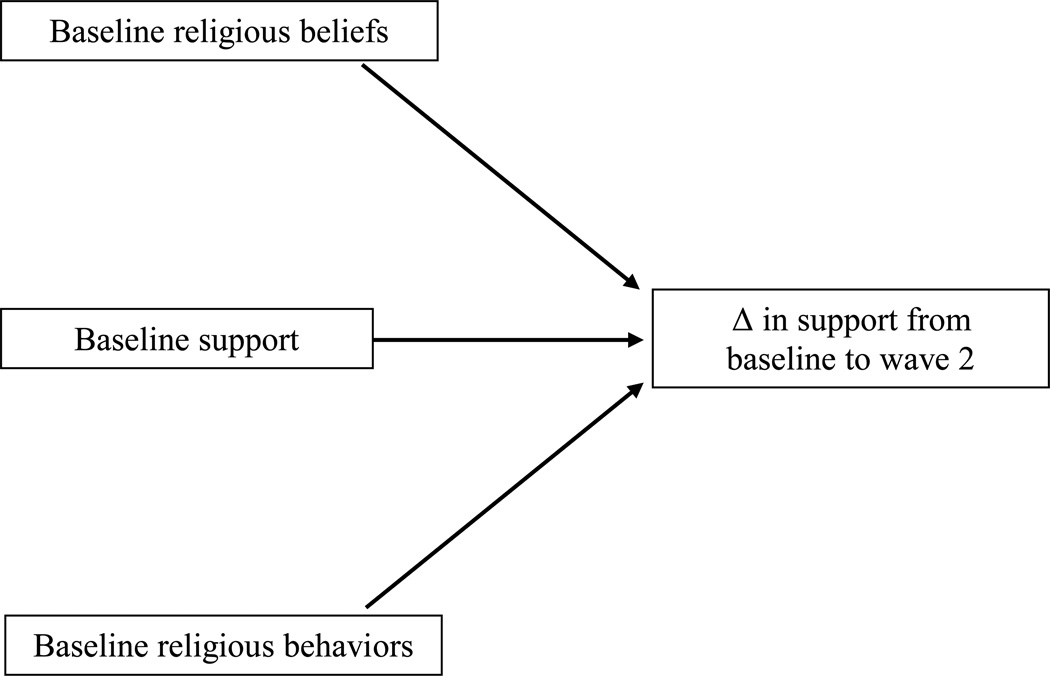

All analyses were conducted using SAS (Version 9.4). Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model that was tested using ordinary least squares regression for the continuous outcomes of change in general or religious social support from baseline to wave 2. The model also includes baseline religious beliefs, baseline religious behaviors, and baseline continuous measures on general or religious social support.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model

Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to determine if change in the continuous measures of general or religious social support from baseline to wave 2 could be predicted from religious beliefs at baseline, religious behaviors at baseline, and continuous measures of general or religious social support from baseline. The 9 support-specific variables included 4 on general social support (social support: all 12 items total; social support: appraisal subscale; social support: belonging subscale; social support: tangible subscale) and 5 on religious support (religious support: all 8 items total; religious support: emotional support received; religious support: emotional support provided; religious support: negative interaction; religious support: anticipated support). Control variables included age, gender, education level, health status, and marital status. Cases with missing data were not used in the analysis.

As retained participants differed from those lost to follow-up in some ways (e.g., educational attainment, relationship status, work status), the results are susceptible to selection bias. As a sensitivity analysis, a Heckman-style two-stage adjustment approach (Heckman 1976; Heckman 1979) was used to correct for the sample selection bias and to obtain the adjusted estimation. The Heckman-style two-stage adjustment involves two steps. First, a selection model was developed to estimate the probability of case loss via probit regression. Age, gender, education, relationship, work status and health status were used as predictors. Second, the inverse Mills ratio calculated from the first step was entered into the multiple linear regression along with other predictors described above to provide adjustment for the missing data bias. The coefficients for the inverse Mills ratio were not statistically significant for any of the general or religious social support outcomes, suggesting that the selection bias was not quantitatively consequential. In addition, there was no change in the significance patterns of the coefficients for religious beliefs and religious behaviors at baseline after Heckman adjustment. Therefore, the results from the original multiple linear regression are reported.

Results

Baseline data included a total of 3,173 participants, of which 1,281 were men and 1,892 were women. There were a total of 1,251 participants during wave 2 of data collection (39% retention). This included 456 men and 795 women. Retained participants averaged at 58 years of age (SD = 13) with a median annual household income of $35,000. The majority of the participants were married or living with a partner (38%), had at least a high school education or equivalent (89%), and were retired (33%).

Table 1 shows the effect of religious involvement on change in general and religious social support from baseline to wave 2. Results suggest that neither baseline religious beliefs nor religious behaviors were associated with change in any aspect of general social support from baseline to wave 2. However, baseline religious behaviors were associated with increased overall (e.g., total score) religious social support from baseline to wave 2 (p<.001). In addition, baseline religious behaviors were associated with increased religious social support from baseline to wave 2 in the each of the religious social support subscales: emotional support received (p<.001), emotional support provided (p<.001), negative interaction (p<.001), and anticipated support (p<.001).

Table 1.

Religious involvement and change in general social support and religious social support from baseline to wave 2a

| Social Support Dimension | Religious Involvement Dimension |

Estimate (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social support - total scale score (n=1167) | Beliefs | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.5520 |

| Behaviors | 0.00 (0.06) | 0.9385 | |

| Social support - appraisal subscale (n=1204) | Beliefs | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.3626 |

| Behaviors | −0.00 (0.02) | 0.9375 | |

| Social support - belonging subscale (n=1195) | Beliefs | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.2891 |

| Behaviors | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.4517 | |

| Social support - tangible subscale (n=1198) | Beliefs | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.7327 |

| Behaviors | −0.00 (0.02) | 0.9545 | |

| Religious social support - total scale score (n=1018) | Beliefs | −0.07 (0.06) | 0.2820 |

| Behaviors | 0.34 (0.06) | <.0001 | |

| Religious social support - emotional support received (n=1080) | Beliefs | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.6236 |

| Behaviors | 0.10 (0.02) | <.0001 | |

| Religious social support - emotional support provided (n=1087) | Beliefs | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.9592 |

| Behaviors | 0.13 (0.02) | <.0001 | |

| Religious social support - negative interaction (n=1072) | Beliefs | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.5635 |

| Behaviors | 0.07 (0.01) | <.0001 | |

| Religious social support - anticipated support (n=1058) | Beliefs | −0.03 (0.02) | 0.1619 |

| Behaviors | 0.10 (0.02) | <.0001 |

Adjusted for the measures at baseline and controlling for age, gender, education level, health status, and marital status.

Discussion

The present study has made an important step toward better understanding how religious involvement is associated with change in religious social support over time. Most theories about the religion-health connection include some form of social support as an explanatory mechanism of that relationship (Holt et al. 2013; Lincoln and Mamiya 1990; George et al. 2002; Ellison et al. 1997; Ellison and Hummer 2010; Musick et al. 1998; Musick et al. 2000; Kanu et al. 2008; Kendler et al. 2003; Krause 2002; Krause 2006). However, the majority of studies that actually test religious social support and general social support as a mediator have been limited in their ability to determine causality due to their cross sectional nature. To substantiate a mediator role, social support temporally must occur as a result of religious involvement, and the current data suggesting that religious involvement at baseline is associated with changes in religious social support over time provides such evidence.

The current study shows a relationship between religious participation and increases in religious social support over a relatively brief time period. In summary, the study found that those who engage in religious behaviors such as attending services, bible study classes, church committee participation, choir singing, etc. are more exposed to other church members and therefore more likely to receive religious support from these networks. As literature has shown, religious support may lead to various methods of coping among African American adults, and in turn may have an effect on mental health outcomes (Prado et al. 2004). One explanation for the observed changes in religious social support over time from religious behaviors compared to religious beliefs can be attributed to the unique dimensions of religious behavior, specifically the aspects of religious involvement/participation (clergy support, faith-based encouragement from congregation members, etc.), which are not engendered through one’s personal religious beliefs. This phenomenon can be attributed to an individual’s exposure to co-religionists (members of a similar religious system). Research has shown that the size and interpersonal dynamics of the congregation can have a significant effect on reports of emotional support and negative interactions among individual members (Ellison et al. 2009). For example, individuals who attend bigger congregations tend to report lower levels of negative interactions, where one of the downsides of social intimacy (e.g. unpleasant encounters with fellow members) can often be sheltered by a sense of anonymity and personal space within a larger church setting (Ellison et al. 2009).

The current results also suggested that only changes in religious social support, as opposed to general social support, were associated with baseline religious participation. This highlights the unique growth in support from religious (e.g., fellow church members, clergy), as opposed to from secular (e.g., neighbors, coworkers, friends) sources, which is stimulated by participation in a faith community. The unique nature of religious social support was reported in its role in health-related outcomes as well (Debnam et al. 2012).

It is important to note that while we observed a consistent pattern of religious behaviors being associated with increases in each dimension of religious social support over time, this also included the negative aspects of religious social support. Negative interactions in the church setting could relate to tensions between church members, and the study findings suggest that being involved with the church appear to be associated with increases in these types of negative interactions over time. This dimension also reflects demands perceived by church attendees from their fellow members (Krause 2003; Krause and Wulff, 2005; Fetzer Institute, National Institute on Aging Working Group 1999), which in this sample increases over time were associated with baseline religious participation. This suggests an escalation of the role-related strain reported by some church members and in particular women and clergy members in many African American churches who often fulfill multiple volunteer roles (Graham-Phillips et al. in review; Krause et al. 1998). Future examination into negative interaction religious support and religious involvement should examine what types of circumstances elicit these negative interactions and how these interactions may influence the religion-and-health relationship.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study had several notable strengths. The study utilized a longitudinal data set that included multidimensional, validated assessments of social support and religious involvement. The ability to examine these complex relationships over time is critical for gaining a better understanding of the connection between religion and health-related outcomes. In addition, the study utilized an adequate sample of respondents comprised of an African American adult population in the United States.

Unfortunately, the study was not without limitations. The results are susceptible to bias due to the self-reported nature of the data. While the study examines the role of religious social support, it is plausible that additional factors are at play that may have influenced the results. Perhaps a person who is involved with church activities is implicitly more extroverted and more likely to benefit from social support networks compared to others. Perhaps most important, we had a modest retention rate. The RHIAA study was not initially designed to retain participants over time (Holt et al. 2015) and thus we did not have the mechanisms in place to do so at baseline. Though retained participants were demographically similar to those lost to follow-up in some ways (e.g., self-reported health status, annual household income), they differed in others (e.g., educational attainment, relationship status, work status), which may have influenced bias.

Implications and Future Research

African Americans who are active in faith communities showed increases in all types of religious social support, even the negative aspects, over a relatively modest longitudinal study period. This illustrates the strength of the church as a social network and the role that it plays in people’s lives. These findings elicit implications for churches to encourage various aspects of social support through church activities, such as through health ministries. Furthermore, the study results showed that, like general social support, there are negative aspects to social support within churches and provides an impetus for church leadership to mitigate these implications through strategies such as conflict resolution training. The study findings emphasize the need for targeted messaging to encourage healthy interpersonal dialogue to address issues within faith communities.

The study has important implications for future research on the influences of religious social support on health among African Americans. The observed change in religious social support (emotional support received/supported; negative interaction) from baseline to wave 2 from religious behaviors, a dimension of religious involvement, paves the way for future longitudinal mediation research examining how religious social support dimensions impact specific health outcomes among church members. Furthermore, a comprehensive longitudinal study would include both mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety etc.) and physical health outcomes to better understand how religious social support impacts overall African American health and well-being.

Acknowledgements

The team would like to acknowledge the work of Opinion America and Tina Madison who conducted participant recruitment/retention and data collection activities for the present study.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, (R01 CA 105202; R01 CA154419) and a grant from the Duke University Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health, through the John Templeton Foundation (#11993). The study was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board (#373528-1).

References

- Biggar H, et al. Women Who are HIV Infected: The Role of Religious Activity in Psychosocial Adjustment. AIDS Care. 1995;11:195–199. doi: 10.1080/09540129948081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle CS, Appel S, Skelly AH, Carter-Edwards L. Mid-Life African American Women with Type II Diabetes: Influence on Work and the Multicaregiver Role. Ethnicity and Disease. 2002;12:555–566. http://www.ishib.org/journal/ethn-12-04-555.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Basic Psychometrics for the ISEL 12 Item Scale. 2009 http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~scohen. [Google Scholar]

- Debnam K, Holt CL, Clark EM, Roth DL, Southward P. Relationship Between Religious Social Support and General Social Support with Health Behaviors in a National Sample of African Americans. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;35(2):179–189. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9338-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupree CY. The Attitudes of Black Americans Toward Advance Directives. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2000;11(1):12–18. doi: 10.1177/104365960001100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, George LK. Religious Involvement, Social Ties, and Social Support in a Southeastern Community. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33(1):46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Hummer RA, et al. Religion, Families and Health: Population Based Research in the United States. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Lee J, Benjamins MR, Krause NM, Ryan DN, Marcum JP. Congregational Support Networks, Health Beliefs, and Annual Medical Exams: Findings from a Nationwide Sample of Presbyterians. Review of Religious Research. 2008;50(2):176–193. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20447560. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Krause NM, Shepherd BC, Chaves MA. Size, Conflict, and Opportunities for Interaction: Congregational Effects on Members’ Anticipated Support and Negative Interaction. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2009;48(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Musick M, Levin J, Taylor R, Chatters L. The Effects of Religious Attendance, Guidance, and Support on Psychological Distress: Longitudinal Findings from the Nation Survey of Black Americans. Paper presented at the annual meetings for the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion; San Diego; November, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Engle VF, Fox-Hill E, Graney MJ. The Experience of Living-Dying in a Nursing Home. Self-Reports of Black and White Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1998;46(9):1091–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, Koch JR. Religion and Health Among Black and White Adults: Examining Social Support and Consolation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33:362–375. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute, National Institute on Aging Working Group. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. Kalamazoo. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining the Relationships Between Religious Involvement and Health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13(3):190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Phillips AG, Holt CL, Mullins CD, Slade JL, Savoy A, Carter R. Use of Evidence-Based Interventions in African American Health Ministries: Facilitators and Barriers. Health Education & Behavior. In Review. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser JM, Kleefield SF, Brennan TA, Fischbach RL. Minority Populations and Advance Directives: Insight From a Focus Group Methodology. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 1997;6(1):58–71. doi: 10.1017/s0963180100007611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement. 1976;5:475–492. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Sample Selection as a Specification Error. Econometrica. 1979;47(1):153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Le D, Calvinelli J, Huang J, Clark EM, Roth DL, Williams B, Schulz E. Participant Retention in a Longitudinal National Telephone Survey of African American Men and Women. Ethnicity & Disease. 2015;25(2):187–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Roth DL, Clark EM, Debnam K. Positive Self-Perceptions as a Mediator of Religious Involvement and Health Behaviors in a National Sample of African Americans. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;37(1):102–112. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9472-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Schulz E, Williams B, Clark EM, Wang MQ. Social Support as a Mediator of Religious Involvement and Physical and Emotional Functioning in a National Sample of African Americans. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2013;17(4):421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis GK, Northcott HC. Religion and Differences in Morbidity and Mortality. Social Science & Medicine. 1987;25(7):813–824. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanu M, Baker E, Brownson RC. Exploring Associations Between Church-Based Social Support and Physical Activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2008;5:504–515. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.4.504. http:// http://www.humankinetics.com/acucustom/sitename/Documents/DocumentItem/15914.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Liu X, Gardner CO, McCullough ME, Larson D, Prescott CA. Dimensions of Religiosity and Their Relationship to Lifetime Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):496–503. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.496. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DE, Bushwick B. Beliefs and Attitudes of Hospital Inpatients About Faith Healing and Prayer. Journal of Family Practice. 1994;39:349–352. http:// http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1995-22864-001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff EA, Landrine H. Acculturation and Cigarette Smoking Among African American Adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;19(5):501–514. doi: 10.1007/BF01857681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, King DE, Carson VB. Handbook of Religion and Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-Based Social Support and Health in Old Age: Exploration Variations by Race. Journal of Gerontology. 2002;57(6):S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring Race Differences in the Relationship Between Social Interaction with the Clergy and Feelings of Self-Worth in Late Life. Sociology of Religion. 2003;64(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Ellison CG, Wulff KM. Church-Based Emotional Support, Negative Interaction, and Psychological Well-Being: Findings from a National Sample of Presbyterians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37(4):725–741. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Wulff KM. Church-Based Social Ties, a Sense of Belonging in a Congregation, and Physical Health Status. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2005;15(1):73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-Based Social Support and Mortality. Journal of Gerontology. 2006;61B(3):S140–S146. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.s140. http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/content/61/3/S140.full.pdf+html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lukwago SL, Kreuter MW, Bucholtz DC, Holt CL, Clark EM. Development and Validation of Brief Scales to Measure Collectivism, Religiosity, Racial Pride, and Time Orientation in Urban African American Women. Family and Community Health. 2001;24(3):63–71. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews HF, Lannin DR, Mitchell JP. Coming to Terms with Advanced Breast Cancer: Black Women’s Narratives from Eastern North Carolina. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;38:789–800. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Blazer DG, Hays JC. Religious Activity, Alcohol Use, and Depression in a Sample of Elderly Baptists. Research on Aging. 2000;22:91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Koenig HG, Hays JC, Cohen HJ. Religious Activity and Depression Among Community-Dwelling Elderly Persons with Cancer: The Moderating Effect of Race. Journal of Gerontology, Series B. Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1998;53(4):S218–S227. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooney J, Woodrum E. Religious Coping and Church-Based Social Support as Predictors of Mental Health Outcomes: Testing a Conceptual Model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The Psychology of Religious Coping: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KD, Sowell RL. Hope and Coping in HIV-Infected African American Women of Reproductive Age. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association. 2000;11(2):18–24. http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/11854985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirutinsky S, Rosmarin DH, Holt CL, Feldman RH, Caplan LS, Midlarsky E, Pargament KI. Does Social Support Mediate the Moderating Effect of Intrinsic Religiosity on the Relationship Between Physical Health and Depressive Symptoms Among Jews? Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;34(6):489–496. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9325-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Feaster DJ, Schwartz SJ, Pratt IA, Smith L, Szapocznik J. Religious Involvement, Coping, Social Support, and Psychological Distress in HIV-Seropositive African American Mothers. AIDS Behavior. 2004;8(3):221–235. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000044071.27130.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DL, Mwase I, Holt CL, Clark EM, Lukwago S, Kreuter MW. Religious Involvement Measurement Model in a National Sample of African Americans. Journal of Religion and Health. 2012;51(2):567–578. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9475-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal MJ, Williams DR, Musick MA, Buck AC. Depression, Anxiety and Religious Life: A Search for Mediators. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:349–359. doi: 10.1177/0022146510378237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoresen CE. The Emerging Role of Counseling Psychology in Health Care. WW Norton & Co; 1998. Spirituality, Health, and Science: The coming revival? [Google Scholar]

- Waters CM. Understanding and Supporting African Americans’ Perspectives on End-of-Life Care Planning and Decision-Making. Qualitative Health Research. 2001;11(3):85–98. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Ford V. Health Protective Behaviors of Rural Black Elderly Women. Health & Social Work. 1992;17(1):28–36. doi: 10.1093/hsw/17.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]