Abstract

Genome editing with targeted nucleases and DNA donor templates homologous to the break site has proven challenging in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), and particularly in the most primitive, long-term repopulating cell population. Here we report that combining electroporation of zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) mRNA with donor template delivery by AAV serotype 6 vectors directs efficient genome editing in HSPCs, achieving site-specific insertion of a GFP cassette at the CCR5 and AAVS1 loci in mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs at mean frequencies of 17% and 26%, respectively, and in fetal liver HSPCs at 19% and 43%, respectively. Notably, this approach modified the CD34+CD133+CD90+ cell population, a minor component of CD34+ cells that contains long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Genome-edited HSPCs also engrafted in immune deficient mice long-term, confirming that HSCs are targeted by this approach. Our results provide a strategy for more robust application of genome editing technologies in HSPCs.

Gene therapy using HSPCs is increasingly being applied to treat severe genetic diseases1–4. A patient’s own HSPCs can be genetically modified following a short ex vivo culture in the presence of hematopoietic cytokines, and integrating viral vectors such as lentiviral vectors are often used to confer long-lasting effects. However the semi-random nature of vector insertion can result in non-authentic patterns of gene expression, including silencing over time, or harmful insertional mutagenesis events, such as transactivation of neighboring oncogenes5–7. In contrast, genome editing with targeted nucleases—which include zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases, and the RNA-guided clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/Cas endonucleases—enables gene disruption, correction of a gene mutation, or insertion of new DNA sequences in a highly regulated manner at pre-selected target sites. These nucleases act by catalyzing site-specific DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs)8. Repair of DSBs can proceed via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR)9–12, and these pathways are exploited to achieve the desired form of genetic modification13. The therapeutic applications of genome editing that are closest to clinical translation are disruption of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 to treat HIV14 and of the γ-globin repressor BCL11A15 as a therapy for β-globinopathies. Both of these programs involve gene knockout, whereas the ability to correct mutations or add DNA sequences would substantially broaden the impact of gene editing technologies.

HDR-mediated genome editing requires the introduction into a cell of both a targeted nuclease and a matched homologous donor DNA repair template. As both components have to be present only transiently to permanently modify a genome, it is possible to deliver them using non-permanent delivery vehicles, including nucleic acids (plasmid DNA, mRNA, oligonucleotides) and certain viral vectors (integrase-defective lentivirus (IDLV), adenovirus, and adeno-associated virus (AAV)). Application of these methods is now quite straightforward for cell lines and a variety of primary cells16–19, but their use in HSPCs can be particularly challenging, especially for insertion of a full transgene expression cassette. Initial attempts at editing human CD34+ HSPCs with integration-defective lentiviral vectors (IDLVs) only achieved levels below 0.1%20. More recently, combining the introduction of ZFNs as mRNA with IDLV donor templates has resulted in the site-specific insertion of GFP cassettes in ~5% of cells in the bulk culture, with a further 2-fold increase possible when HSPCs were subject to an extended incubation in the presence of dmPGE2 and SR121. However analysis of editing rates in the most primitive HSPCs, identified by expression of CD9022,23 or by studies involving transplantation of cells into immune-deficient mice, have highlighted the difficulty of editing the most primitive long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) compared to the more differentiated subsets that are also present within the bulk CD34+ HSPC population21,24.

In the present study we evaluated the potential of AAV vectors to function as homologous donor templates. By identifying AAV serotype 6 as a capsid variant with high tropism for human HSPCs, and combining this method of donor delivery with mRNA delivery of ZFNs, we were able to demonstrate dose-dependent site-specific insertion of small or large gene cassettes at two different endogenous loci. The high levels of genome editing observed in bulk CD34+ HSPC populations were also maintained in cells with more primitive characteristics, leading to the long-term multi-lineage production of gene-modified cells following transplantation into immune-deficient mice.

Results

Human HSPCs are efficiently transduced by AAV6 vectors

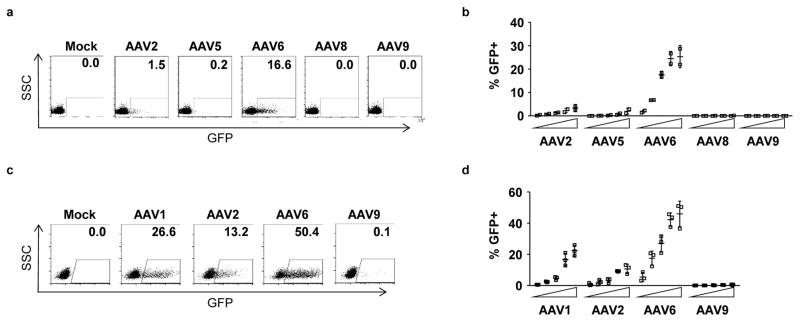

In order to evaluate the ability of AAV vectors to serve as homologous donors for genome editing in HSPCs, we first compared the ability of different AAV capsid serotypes to transduce these cells. We used AAV vectors expressing GFP reporter genes, and packaged into capsids from serotypes 1, 2, 5, 6, 8 and 9. These were evaluated at a range of doses on CD34+ HSPCs isolated from either mobilized peripheral blood or fetal liver.

For both types of HSPC, we found that AAV serotype 6 gave the highest rates of transduction across a range of vector doses (Fig. 1). The next most efficient serotype was the closely related variant, AAV1. This agrees with prior reports describing the tropism of AAV6 vectors for human HSPCs25–27.

Figure 1. HSPCs are efficiently transduced by AAV serotype 6.

Mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs (a,b) or fetal liver CD34+ HSPCs (c,d) were transduced with increasing doses of GFP-expressing AAV vectors of the indicated serotypes, and GFP expression was determined at 2 days (fetal liver) or 3–5 days (mobilized blood) post-transduction by flow cytometry. The vector panel for each cell type were from independent manufacturing sources, and the doses used were 1 × 103, 3 × 103, 1 × 104, 3 × 104 and 1 × 105 vector genomes (vg)/cell for mobilized blood HSPCs, and 1 × 102, 5 × 102, 1 × 103, 5 × 103 and 1 × 104 vg/cell for fetal liver HSPCs. Data from representative experiments at doses of 1 × 104 vg/cell are shown (a,c), together with the mean data +/− SD from 2 (mobilized blood) and 3 (fetal liver) experiments using independent HSPC donor sources (b,d).

HDR-mediated editing in HSPCs by ZFN mRNA and AAV6 donors

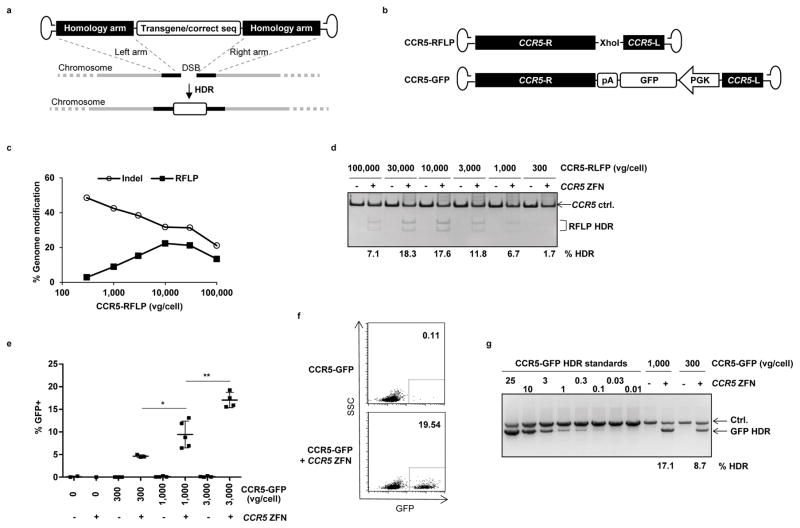

We examined the ability of AAV6 vectors to deliver a homologous donor template to mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs and thereby direct HDR-mediated genome editing in cells also treated with a targeted nuclease (Fig. 2a). We transduced the cells with varying doses of AAV6 vectors, followed by electroporation 16–24 hours later with mRNA expressing a previously characterized CCR5 ZFN pair28. Two different homologous donor templates were evaluated as AAV6 vectors, representing both base pair–specific gene editing events (exemplified by the insertion of a restriction site) and insertion of a larger GFP expression cassette. In each case, the AAV6 vectors contained identical homologous CCR5 sequences flanking either an XhoI restriction site (donor CCR5-RFLP) or a PGK-GFP expression cassette (donor CCR5-GFP) (Fig. 2b). As these cassettes contain additional sequences between the ZFN binding sites, neither the donor template themselves nor a successfully edited target site would be subject to re-cutting by the CCR5 ZFNs24,29,30. The rates of genome editing events were monitored by population deep sequencing and RFLP analysis to detect the XhoI insertion, or by flow cytometry and semi-quantitative PCR for site-specific GFP addition.

Figure 2. Combination of ZFN mRNA and AAV6 vectors promotes high levels of site-specific genome editing at the CCR5 locus in HSPCs.

(a) Schematic showing use of AAV vector as a template for homology directed repair (HDR) of a double-strand break (DSB), as induced by target-specific nucleases. (b) Schematic of AAV vector genomes containing CCR5 homology donors. R and L refer to CCR5 genomic sequences, comprising 1431 and 473 bp respectively, and inserted in antisense orientation when compared to the AAV genome20. Vector CCR5-RFLP contains an additional Xho1 restriction site and vector CCR5-GFP contains a promoter GFP cassette with a polyadenylation (pA) sequence. (c) Mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs were transduced with AAV6 vectors carrying the CCR5-RFLP donor at indicated doses for 16 hours, then electroporated with CCR5 ZFN mRNA (120μg/ml). Cells were analyzed 3–5 days post-electroporation by deep sequencing to measure the efficiency of genome modification (% indels and site-specific RFLP insertions). Results from one representative of 3 experiments using 3 different HSPC donors are shown. (d) Dose-dependent insertion of XhoI site at CCR5, confirmed by RFLP analysis. One representative experiment is shown, with % HDR quantitation for any sample greater than background. (e) Mobilized blood HSPCs were treated as described, but using CCR5-GFP donor vectors, with and without CCR5 ZFN mRNA electroporation. Cells were collected 3–6 days post-transduction and analyzed by flow cytometry for % GFP+. Results were combined from 5 experiments using 4 different donors and show mean +/− SD. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, unpaired t-test. (f) Flow cytometry plots from one representative experiment using 3,000 vg/cell CCR5-GFP donor, at 6 days post-electroporation. (g) Confirmation of targeted integration of GFP expression cassette at the CCR5 locus by semi-quantitative In-Out PCR, for one representative experiment. Ctrl. is a PCR that serves as a genomic DNA loading control. The % HDR-mediated insertion of GFP was estimated following normalization and by comparison to standards, and numbers are shown for any samples greater than background. Uncropped images of all gels in this figure are available in Supplemental Figure 10.

NHEJ and HDR repair are competitive events, and the products of both repair pathways were detected in the treated cell populations by deep sequencing (Fig. 2c, Supplemental Table 1). Increasing the dose of the CCR5-RFLP vector led to an increase in the rate of XhoI insertion at the CCR5 locus, resulting in > 20% of alleles being modified (Fig. 2c). This was accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the frequency of the indels characteristic of NHEJ-mediated repair, whereas at the highest levels of the AAV6 donor, cytotoxicity led to a decrease in both types of genome editing events (Fig. 2c,d). Similarly, increasing levels of stable GFP expression were observed following transduction of the cells with increasing doses of the CCR5-GFP vector, but only in the presence of the CCR5 ZFN mRNA (Fig. 2e–g).

The optimal time for AAV6 transduction relative to ZFN mRNA electroporation was evaluated and found to be between 24 hours pre- and 1 hour post-electroporation, indicating that this sequential treatment schedule is relatively flexible (Supplemental Fig. 1). The amount of HDR editing at the CCR5 locus achieved under specific conditions also varied between different CD34+ donors (Supplemental Fig. 2). For example, using AAV6 vector doses of 3,000 vg/cell, we achieved a mean rate of RFLP insertion in CCR5 of 15.8% (range 8.4–29.2, n=15 experiments), whereas a dose of 10,000 vg/cell resulted in a mean rate of 20.1% (range 11.4–32.5, n=11). These levels of HDR-mediated genome editing were also independent of the HSPC cell source because treatment of fetal liver–derived CD34+ cells with the CCR5-GFP vector and CCR5 ZFN mRNA produced similar high levels of stable and site-specific GFP addition (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Programmable site-specific nucleases, including ZFNs, can introduce off-target DNA breaks at sequences with homology to the intended target site31, although engineering strategies can minimize such effects32–34. In the absence of more extensive homology between an off-target break site and a donor sequence, as is often be the case, the most frequent genome editing outcome is NHEJ-mediated repair, which can lead to indels28,35. The off-target profile of the CCR5 ZFNs used in this study have been previously described28,35,36, and deep sequencing of the top 23 known off-target sites in cells treated with the combination of CCR5 ZFNs and the CCR5-GFP donor gave the expected profile (Supplemental Table 2).

To establish the generality of these results we performed an analogous set of studies using reagents specific for the AAVS1 ‘safe harbor’ locus37,38. In mobilized blood HSPCs, insertion of a HindIII restriction site occurred, on average, at 28% of the AAVS1 alleles, whereas GFP addition was observed in > 30% of the cells (Supplemental Fig. 4). Similar high rates of gene editing at AAVS1 were achieved in fetal liver HSPCs, with stable GFP addition detected in >40% of the cells, without any toxicity (Supplemental Fig. 5). Taken together, these results demonstrate that AAV6 vectors are an effective vehicle for delivering homologous donor DNA templates to CD34+ HSPCs, and that when combined with ZFN mRNA electroporation, the protocol supports both base pair–specific genome editing events and larger gene additions at frequencies in the range of 15 to 40%.

AAV6 vectors use HDR pathways to genetically modify HSPCs

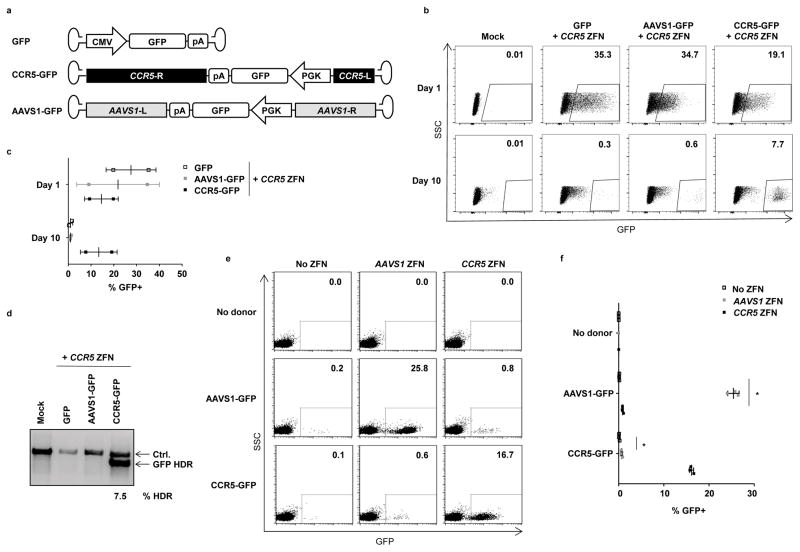

In addition to engaging the cell’s HDR pathways to achieve precise on-target genome editing, AAV genomes can also become inserted at the site of a DSB through NHEJ-mediated end-capture events39–41. Such events represent on-target gene additions when occurring at the intended nuclease target site, but are considered off-target when occurring at DSBs generated by either random cellular events or any off-target activity of the nuclease itself (Supplemental Fig. 6a). To further investigate which mechanism was responsible for the high levels of stable GFP expression observed following the introduction of ZFNs and AAV6 donors into cells, we combined CCR5 ZFN mRNA treatment of HSPCs with AAV6 vectors containing GFP expression cassettes but lacking sequences with homology to CCR5. These included a GFP vector with no flanking genomic regions, and one with mismatched arms that were instead homologous to the AAVS1 locus (Fig. 3a). As before, the vectors were introduced into the cells and followed one day later by CCR5 ZFN mRNA electroporation.

Figure 3. Site-specific genome editing by AAV6 vectors uses homology directed repair.

(a) Schematic of AAV vectors used, which all contain a GFP expression cassette. Vector CCR5-GFP additionally contains 1431 and 473 bp sequences with homology to the CCR5 locus, while vector AAVS1-GFP contains 801 and 840bp of sequences with homology to the AAVS1 (PPP1R12C) genomic locus61. (b) Fetal liver HSPCs were mock treated (Mock), or transduced with 1,000 vg/cell of the indicated AAV vectors for 24 hours, then electroporated with CCR5 ZFN mRNA. Cells were analyzed for GFP by flow cytometry at day 1 and day 10 post-electroporation. Shown is data from one representative experiment, and (c) mean +/− SD GFP+ for n=2 fetal liver tissues. (d) Evaluation of targeted integration of GFP at the CCR5 locus by semi-quantitative In-Out PCR, for one representative experiment. The Ctrl. PCR serves as a loading control. Quantitation for the single sample above background control is shown. An uncropped image of this gel is available in Supplemental Figure 11. (e) Mobilized blood HSPCs were transduced without or with AAVS1-GFP or CCR5-GFP donors at 10,000 vg/cell for 16 hours, and/or electroporated with AAVS1 or CCR5 ZFN mRNA. Cells were analyzed 8 days post-electroporation by flow cytometry. Shown is data from one representative experiment, and (f) mean ± SD GFP+ expression from n=3 samples, except that the no donor, AAVS1 ZFN and no donor, CCR5 ZFN treatments were n=1. * p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

Using fetal liver–derived HSPCs, we observed that all three vectors produced similar initial frequencies of GFP+ cells at one day post electroporation. This reflected expression of GFP from the episomal AAV vectors, and confirmed equivalent rates of introduction of each of the AAV vectors into HSPCs. However, by day 10, only the cells receiving the AAV6 vector with CCR5 homology arms retained significant levels of GFP expression (Fig. 3b,c). In addition, the MFI of GFP expression in these cells was considerably less variable than in any of the day 1 populations, as would be expected if gene expression was occurring subsequent to a mostly site-specific integration event. Low levels of GFP+ cells were also apparent in the day 10 cultures of cells receiving CCR5 ZFNs and vectors without CCR5 homologous arms. Such expression likely resulted from both residual episomal AAV genomes and following end-capture of the AAV genomes into DSBs, including those generated at the CCR5 locus by the ZFNs. Finally, a semi-quantitative site-specific PCR assay confirmed that GFP expression in the CCR5-GFP plus CCR5 ZFN day 10 population resulted from insertion of the GFP cassette at the CCR5 locus, and that this HDR-dependent event only occurred when flanking CCR5 sequences where included in the AAV6 vector genome (Fig. 3d).

Similar results were obtained with mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs. Here, stable GFP expression after 8 days of culture was only observed when matched combinations of ZFNs and AAV6 donors where used, capable of inserting GFP expression cassettes at either the CCR5 or AAVS1 loci (Fig, 3e,f). Although low but statistically significant levels of GFP+ cells were observed when the mismatched combinations of AAV6 donors and ZFNs were used, presumably due to end-capture of AAV genomes at the ZFN-generated DSBs, these occurred at only ~4% of the rate that on-target HDR-mediated events occurred at each locus when matched reagents were used (Supplemental Figure 6b,c). It is also likely that such events would occur at even lower frequencies when the matched combinations of reagents were used, as they would also be in competition with HDR-mediated pathways.

In summary, the requirement for matched homologous sequences to support the highest levels of gene addition at the CCR5 and AAVS1 loci identifies HDR pathways as the predominant mechanism leading to stable genome editing in HSPCs.

Analysis of AAV6 and ZFN treated HSPCs

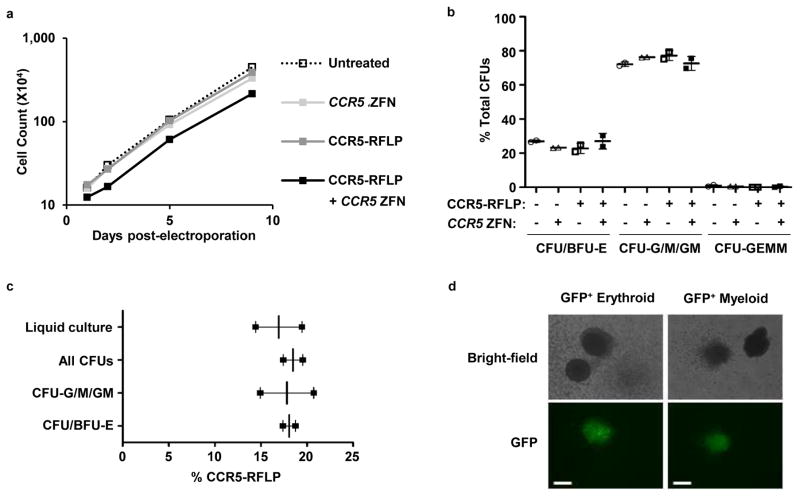

We examined the ability of mobilized blood HSPCs treated with the CCR5-RFLP vector plus CCR5 ZFN mRNA to proliferate in culture, to differentiate into hematopoietic lineages, and to maintain consistent levels of genome-edited cells in the population. When the cells were grown in bulk culture, we observed an initial decrease of 23% in the absolute number of cells present in the population treated with both vector and ZFNs at one day post-electroporation, compared to the other arms of the experiment. However, by two days post-electroporation, the rate of growth of these cells had become indistinguishable from a mock-treated population (Fig. 4a). In addition, the frequency of genome-edited events in the population did not vary over 9 days of culturing, with the frequency of site-specific RFLP insertions being 19.56% at day 2 and 19.45% at day 9. Together, these data indicate that although some of the cells in the bulk CD34+ population were sensitive to the AAV6 plus ZFN treatment, the proliferative potential of the surviving cells was not affected, suggesting that any such effects could be compensated for by using higher initial numbers of cells.

Figure 4. Rates of bulk culture cell growth and genome modification in erythroid and myeloid lineages.

(a) Mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs were transduced with 1,000 vg/cell CCR5-RFLP donor, and/or electroporated 16 hrs later with 40 μg/ml of CCR5 ZFN mRNA. Mock treated HSPCs were cultured as a control. Cells were counted at 1–9 days post-electroporation. Results are shown from one representative experiment from a total of 3 independent experiments using 3 different HSPC donors. (b) Cells were also subjected to colony formation assay at 24 hours post-electroporation, with CFUs evaluated 14 days later. Mean +/− SD from duplicated samples are shown. No significant differences were detected among the 4 treatment conditions (p>0.05, one-way ANOVA). (c) CFUs were also genotyped by deep sequencing to detect rates of insertion of the XhoI site. Between 23 and 88 validated individual colonies were picked for each colony type. Mean +/− SD from 2 combined experiments using different HSPC donors are shown. No significant differences were detected (p>0.05, one-way ANOVA). (d) Mobilized blood HSPCs treated with CCR5-GFP donor and CCR5 ZFN mRNA were used for colony formation assays. Representative GFP+ erythroid and myeloid colonies are shown. The white bars represent 100μm.

We also plated AAV6 and ZFN treated cells in methylcellulose and analyzed the colonies that formed. Here, we found no difference in the relative percentages of the different colony subtypes that developed in the various treatment arms of the experiment (Fig. 4b). In addition, by picking colonies from the methylcellulose cultures and analyzing their genotype, we confirmed that the levels of genome editing in the myeloid colonies (colony-forming unit – granulocyte/macrophage/granulocyte and macrophage, CFU-G/M/GM) and erythroid colonies (burst forming unit-erythroid, BFU-E, and CFU-E) were indistinguishable from the levels in the bulk liquid culture (Fig. 4c). The numbers of CFU-granulocyte/erythroid/macrophage/megakaryocyte (GEMM) obtained for all conditions were too low to quantitate. Finally, in a similar experiment using the CCR5-GFP vector, we observed GFP+ cells in all colony types (Fig. 4d). Taken together, these data indicate that the combined AAV6 transduction/ZFN mRNA treatment does not adversely impact the growth or differentiation potential of HSPCs.

Efficient genome editing in primitive subsets of CD34+ HSPC

CD34+ cells comprise a mixed population of primitive and more differentiated cells that can be further distinguished based on the expression of additional markers23. The CD90+ subset in particular has been associated with long-term repopulating activity22,42,43, and CD34+CD90+ cells can provide long-term multi-lineage engraftment in patients undergoing cancer treatment44,45. However, the most primitive cells, including those defined as CD34+CD133+CD90+, or capable of persisting in transplanted immune-deficient mice, have proven to be the most difficult to edit when ZFNs have been combined with donor templates delivered by IDLVs21,24.

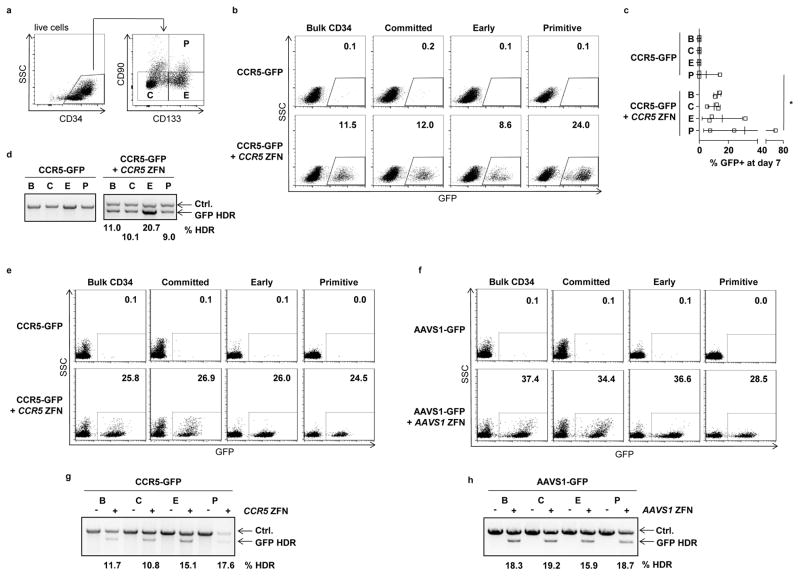

To evaluate the ability of AAV6 donors to promote HDR-mediated gene editing in primitive cells, we treated bulk CD34+ populations isolated from fetal liver with CCR5-GFP AAV6 vectors and CCR5 ZFN mRNA, then sorted into different subsets. We defined subsets within the bulk (B) CD34+ population as primitive (P), early (E) and committed (C) progenitors, based on expression of CD133 and CD9021,23 (Fig. 5a). We cultured each population for a further 7 days, then measured the levels of stable GFP expression in the different populations by flow cytometry. We readily detected stable GFP expression in each of the subsets, with no statistically significant difference in the levels in the most primitive cells compared to either the bulk unsorted CD34+ population or other sorted subsets (Fig. 5b,c). These observations were further validated by performing site-specific In-Out PCR to confirm insertion of GFP at the CCR5 locus (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5. Genome editing in different HSPC subsets.

(a) Representative flow cytometry plot showing different subsets within fetal liver CD34+ HSPCs, defined as primitive (P) early (E) and committed (C) progenitors. (b) Fetal liver HSPCs were treated with 1,000 vg/cell CCR5-GFP vectors for 24 hours and then electroporated with 40 μg/ml CCR5 ZFN mRNA. One day later the cells were sorted into the indicated populations based on expression of CD133 and CD90. Control cells received only the CCR5-GFP vectors. Cells were cultured for a further 7 days followed by analysis for GFP expression. Representative day 7 flow cytometry plots are shown from both the unsorted and sorted populations in each treatment arm, and (c) Mean +/− SD GFP+ cells at day 7, for n=3 independent CD34+ sources. No significant differences (p>0.05) were observed between subgroups C, E and P in the CCR5-GFP plus CCR5 ZFN treated groups, one-way ANOVA. * p<0.05, unpaired t-test. (d) In-Out PCR showing levels of GFP insertion at the CCR5 locus in the indicated subsets of fetal liver CD34+ cells. The Ctrl. PCR serves as a loading control. Numbers for values above background controls are shown. (e) Mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs were transduced with 10,000 vg/cell CCR5-GFP, with or without electroporation 16 hours later with 60 μg/ml CCR5 ZFN mRNA. Eight days later, cells were analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry in the indicated subsets. The gating strategy used to isolate the P, E and C populations from the bulk CD34+ population is shown in Supplemental Figure 12a. (f) Mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs were treated as in (e), but using 10,000 vg/cell AAVS1-GFP and 40 μg/ml AAVS1 mRNA. (g) In-Out PCR to detect GFP insertion at the CCR5 locus in the indicated subsets and treatments. Numbers for values above background controls are shown. (h) In-Out PCR to detect GFP insertion at the AAVS1 locus in the indicated subsets and treatments. Numbers for values above background controls are shown. Uncropped images of all gels in this figure are available in Supplemental Figure 12.

Cultured fetal liver HSPCs are quite proliferative, which may increase their permissiveness to HDR-mediated repair. We therefore repeated these experiments using the more clinically relevant mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs, and using reagents targeting both the CCR5 and AAVS1 loci. These analyses also demonstrated equivalent levels of HDR-mediated gene addition in the CD34+CD133+CD90+ population as in the bulk CD34+ population or the more differentiated progenitors (Fig. 5e–h). Taken together, these data suggest that the combination of ZFN mRNA electroporation and AAV6 donor template delivery provides the capability of editing even the most primitive compartment of CD34+ HSPCs.

Genome edited HSPCs engraft and differentiate in NSG mice

The long-term engraftment potential of human HSC can be evaluated by the ability to engraft and differentiate in immune-deficient mice. Such SCID-repopulating cells are considered surrogates for long-term repopulating HSCs46. In mouse HSC studies, long-term-repopulating HSCs are also defined by the ability to further persist during secondary transplantations23,47–50. However, as it is especially difficult to demonstrate secondary transplantations when using mobilized blood CD34+ cells51, we first used fetal liver–derived cells for these analyses.

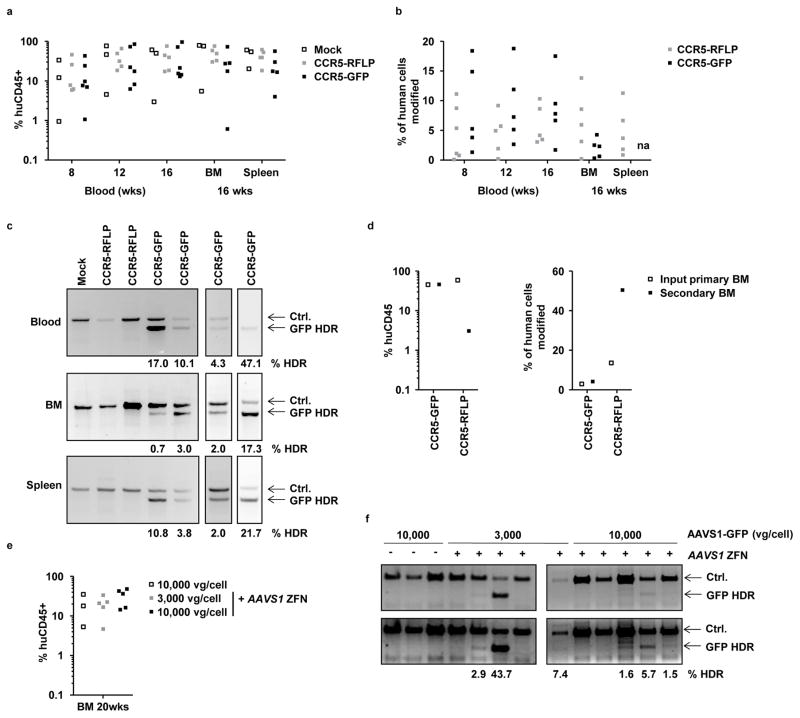

Fetal liver CD34+ cells were transduced with CCR5-GFP or CCR5-RFLP vectors followed by electroporation with CCR5 ZFN mRNA, then engrafted into neonatal NSG mice and monitored over 16 weeks. Analysis of peripheral blood at weeks 8, 12 and 16 post-transplantation, and the bone marrow and spleen at 16 weeks, revealed robust development of human CD45+ leucocytes at levels that were indistinguishable from mice receiving untreated control HSPCs (Fig. 6a). At each time point, the human cells were further stained for lineage specific markers and analyzed for the presence of B cells (CD19+), monocytes (CD3−CD4+), CD4 T cells (CD3+CD4+) and CD8 T cells (CD3+CD4−) (Supplemental Fig. 7). This revealed that the treated HSPCs were capable of differentiating into each lineage at rates similar to untreated cells, confirming no difference in hematopoietic potential for the treated cells, and agreeing with the observations from the in vitro CFU analyses (Fig. 4)

Figure 6. Engraftment of NSG mice with gene edited HSPCs.

(a) Neonatal NSG mice were engrafted with fetal liver HSPCs, either mock treated, or treated with AAV6 donors (CCR5-GFP or CCR5-RFLP) plus CCR5 ZFN mRNAs, using 2 different donor tissues. Genome editing levels in these input HSPCs were 9.1% and 12% for CCR5-GFP treated cells, by flow cytometry, and 6.7% and 11.2% for CCR5-RFLP treated cells, by deep sequencing. Peripheral blood of the mice was analyzed at weeks 8, 12, and 16 for the % of human CD45+ cells, and bone marrow (BM) and spleen were analyzed at 16 weeks. Shown is the combined data from the two separate cohorts of mice. No significant differences were found in the levels of human cells in the blood or tissues between mock and treated samples (two-way ANOVA). (b) Rates of genome modification in human cells were measured in blood and tissue samples from individual mice by flow cytometry for GFP insertions, or deep sequencing for RFLP insertions; na, not available due to high background autofluorescence of cells. Actual numbers are available in Supplemental Table 3. Cells from mock-treated mice gave only background levels in all assays (not shown). (c) Representative examples of In-Out PCR showing GFP addition at the CCR5 locus in peripheral blood, bone marrow, and spleen from individual mice at 16 weeks post engraftment. Numbers for any samples above the levels of the background controls are shown. (d) Bone marrow was isolated at 16 weeks post-engraftment from 2 mice each from the CCR5-GFP or CCR5-RFLP cohorts and was pooled. The levels of human CD45+ cell engraftment and gene modification (GFP+ by flow cytometry, RFLP insertion by deep sequencing) were measured in the pooled cell populations. Each primary BM pool was used to transplant a separate adult female NSG mouse and, 20 weeks later, bone marrow was isolated from the secondary transplant recipients and analyzed for human CD45+ content and levels of genome modification in the same way. (e) Mobilized blood HSPCs were treated with AAVS1-GFP vectors, with and without AAVS1 ZFN, and used to engraft NSG mice. The frequency of GFP+ cells in the input HSPCs, measured at 5 days post-transfection in culture, were 0.72%, 20.5% and 30.7% respectively, for cells receiving 10,000 vg/cell AAVS1-GFP alone, 3,000 vg/cell AAVS1-GFP plus ZFNs and 10,000 vg/cell AAVS1-GFP plus ZFNs. At 20 weeks, bone marrow was isolated and analyzed for human CD45+ leucocytes. (f) Detection of GFP insertion at the AAVS1 locus in bone marrow samples from individual mice, measured by In-Out PCR. Numbers for any samples above the levels of the background controls are shown. Uncropped images of all gels in this figure are available in Supplemental Figure 13.

We also examined the levels of genome editing in the human cells that developed in the mice over time. Using flow cytometry for cells from the CCR5-GFP mice or deep sequencing for the CCR5-RFLP mice, we readily observed edited cells in both the circulation and tissues. This was detected in both the bulk human CD45+ cell populations (Fig. 6b), as well as in individually sorted lineages (Supplemental Fig. 8). Evidence of site-specific GFP insertion at the CCR5 locus was also confirmed in the blood and tissues of individual mice from the CCR5-GFP plus ZFN cohort by In-Out PCR (Fig. 6c). Together, these results demonstrate that modified human HSPCs are capable of engrafting mice and differentiating into multiple different lineages that retain the genomic edits.

Finally, we evaluated the ability of the genome-edited human HSPCs to persist during secondary transplantations47. Bone marrow was harvested from two mice from each of the separate CCR5-GFP or CCR5-RFLP cohorts and was pooled and used to transplant one additional adult NSG mouse for each group. The bone marrow of these secondary transplant recipients was then analyzed 20 weeks later, revealing that these cells had frequencies of genome editing that were at similar or higher levels when compared to the input primary bone marrow samples (Fig. 6d). As these cells had persisted for a total of 36 weeks in the mice and survived during secondary transplantation, the data support the conclusion that long-term SCID-repopulating cells in the initial population of treated CD34+ cells had been modified.

We also evaluated the extent of genome editing that could be detected in the human cells that persisted long-term (20 weeks) in NSG mice transplanted with mobilized blood HSPCs (Fig. 6e). These cells do not transplant NSG mice as robustly as fetal liver HSPCs, and the graft declines over time23,36,51,52 (Supplemental Figure 9), making it more difficult to obtain molecular data from human cells at later time points. NSG mice were engrafted with mobilized blood HSPCs that had been treated with AAVS1-GFP vectors, in the presence or absence of the matched AAVS1 ZFNs, and maintained for 20 weeks. Using an In-Out PCR assay, we were able to demonstrate site-specific GFP insertion at the AAVS1 locus in bone marrow from 6/10 of the mice receiving both the AAV6 vectors and ZFNs, whereas none of the three mice receiving just the AAV6 vectors were positive in the same assay (Fig. 6f). The observation of long-term persistence of the GFP cassette at the targeted AAVS1 locus is also consistent with an ability to edit the most primitive cells in the mobilized blood CD34+ cell population.

Discussion

Precision genome engineering through the use of targeted nucleases is likely to be especially important when the cellular target is a long-lived cell such as an HSC. Achieving HDR-mediated gene editing at efficient levels requires optimization of several steps. First, the targeted nuclease must be introduced into the cell at sufficiently high levels and without toxicity. Next, a homologous donor template must also be introduced. This template can be single-stranded or double-stranded DNA, and presented as a viral vector, bacterial plasmid or synthesized oligonucleotide20,29,30, although the size limitations of oligonucleotides makes them more suited for gene correction purposes than transgene addition. A major limitation here for HSPCs can be cytotoxicity, and we have found that plasmid DNA and adenoviral vectors are less well tolerated in HSPCs than in transformed cells36. Finally the template must engage the HDR machinery, which is most active in the S/G2 phase of the cell cycle53. In the case of CD34+ HSPCs, a further requirement for many applications is that all of these events occur in the most primitive long-term repopulating stem cells, which represent only a minority of the CD34+ population54.

We found mRNA electroporation to be a highly effective method to deliver ZFNs21,30 as it resulted in high levels of DNA cleavage at the targeted CCR5 or AAVS1 loci without overt cytotoxicity. We further found that mRNA delivery of ZFNs could be effectively combined with donor template delivery by AAV vectors to achieve HDR-mediated genome editing, with a certain amount of flexibility in the sequence and timing of the two events. A potentially rate-limiting step of transduction of HSPCs by the AAV vectors was overcome by using the HSPC-tropic serotype AAV6. The combination of ZFN mRNA and AAV6 vectors allowed site-specific insertion of a promoter-GFP cassette at the CCR5 and AAVS1 loci at mean frequencies of 17% and 26%, respectively, in mobilized blood HSPCs, and at 19% and 43% in fetal liver HSPCs.

AAV vectors, in the absence of nuclease, have previously been used to promote HDR55–57, and have found applications in transgenics58. The AAV genome exists in single-stranded and double-stranded forms, both of which could potentially serve as substrates for HDR, and it has been suggested that AAV inverted terminal repeats may be particularly recombinogenic59,60. The capsid packaging limitation of 4.7kb can easily accommodate the homology arms necessary to introduce a small gene correction. Furthermore, for gene insertion applications, the specific homology arms we used to target the AAVS1 locus could allow an additional gene cassette of approximately 3.0 kb. AAV vectors also have the advantage that they are relatively easily manufactured at high titers for clinical applications.

An important consideration when working with CD34+ HSPCs is the ability to modify the most primitive cells in the population, which contribute to ongoing multi-lineage hematopoiesis44,45. Previous work using IDLV donors has shown that although rates of HDR in the bulk CD34+ population reach ~12% (GFP+ cells) when used in combination with dmPGE2 and SR1 stimulation, the vectors supported much lower levels of editing in long-term-repopulating HSCs, as seen in both in vitro cultures and humanized mice experiments21,24. In contrast, we found that donor templates provided as AAV6 vectors were able to direct high levels of genome editing in even the most primitive CD34+CD133+CD90+ subset of cells in vitro, without additional manipulation, and at rates that were indistinguishable from those of the bulk CD34+ population. In addition, the treated HSPCs supported long-term multi-lineage engraftment of humanized mice, including secondary transplantations, consistent with modification of long-term-repopulating HSCs. Furthermore, our data suggest that there is not an inherent defect in the HDR machinery in long-term-repopulating HSCs, at least when the cells are cultured ex vivo for short periods of time.

In summary, our data demonstrate that homologous donor template delivery by AAV6 vectors can be combined with ZFN mRNA electroporation to achieve high levels of precise genome editing in human HSPCs, including in the most primitive populations. As HDR acts downstream of DSB formation, it is likely that AAV6 vectors will have similar utility as partners for all classes of targeted nucleases for this cell population. In this way they provide a means of broadening the application of genome engineering for the treatment of human diseases of the blood and immune systems.

ONLINE METHODS

Isolation of human CD34+ HSPCs

Leukopaks containing G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs were purchased (Apheresis Care Group, Inc. San Francisco, CA) and CD34+ HSPCs purified by magnetic bead selection using a CliniMACS cell selection device (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The enriched CD34+ HSPCs were resuspended in mobilized blood CD34 maintenance media: X-Vivo 10 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (PSA) (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and 100 ng/mL each of stem cell factor (SCF), fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (flt-3) ligand and thrombopoietin (TPO) (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ,).

Fetal liver samples were obtained from Advanced Bioscience Resources (Alameda, CA) or Novogenix Laboratories (Los Angeles, CA), as anonymous waste samples, with approval of the University of Southern California’s Institutional Review Board. Human CD34+ HSPCs were isolated from the tissues following physical disruption and incubation in collagenase to give single cell suspensions, followed by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) (Miltenyi Biotec), as previously described47. Fetal liver–derived HSPCs were cultured in fetal liver CD34 maintenance media consisting of X-Vivo 15 (Lonza) supplemented with 50ng/ml each of SCF, Flt3 ligand and TPO (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), plus 1% PSA.

ZFN reagents

ZFNs targeting the CCR5 and AAVS1 loci have been described previously28,61. The following FokI variants were used to construct obligate heterodimeric versions of ZFNs62: EL:KK (CCR5, experiments with mobilized blood CD34+ cells), ELD:KKR (CCR5, experiments with fetal liver CD34+ cells; AAVS1). An optimized pair of the AAVS1-targeting ZFNs was used in this study (Supplemental Fig. 14). The ZFN coding sequences were cloned into a modified version of plasmid pGEM4Z (Promega, Madison, WI) containing a sequence of 64 alanines 3′ of the inserted gene sequence63, which was linearized by SpeI digestion to generate templates for mRNA synthesis. mRNA was prepared using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE® T7 ULTRA Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) or by TriLink Biotechnologies (San Diego, CA).

AAV vectors

All AAV vectors were produced at Sangamo BioSciences as described below, except for CMV-GFP reporter vectors of different serotypes, used to transduce fetal liver CD34+ cells, which were purchased from the University of Pennsylvania Vector Core (Philadelphia, PA). CCR5 and AAVS1 homologous donor templates 16,20,64 were cloned into a customized plasmid pRS165 derived from pAAV-MCS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), containing AAV2 inverted terminal repeats, to enable packaging as AAV vectors using the triple-transfection method 65. Briefly, HEK 293 cells were plated in 10-layer CellSTACK chambers (Corning, Acton, MA), grown for 3 days to a density of 80%, then transfected using the calcium phosphate method with an AAV helper plasmid expressing AAV2 Rep and serotype specific Cap genes, an adenovirus helper plasmid, and an AAV vector genome plasmid containing inverted terminal repeats. After 3 days the cells were lysed by 3 rounds of freeze/thaw, and cell debris removed by centrifugation. AAV vectors were precipitated from the lysates using polyethylene glycol, and purified by ultracentrifugation overnight on a cesium chloride gradient. Vectors were formulated by dialysis and filter sterilized.

Genome editing of HSPCs

CD34+ HSPCs were stimulated for 16–24 hours in cell source appropriate maintenance media, then transduced with AAV vectors at the indicated vector genome (vg) copy per cell in maintenance media, at a concentration of 1–2 × 106/ml, for 16–24 hours or the indicated time. The HSPCs were washed 2–3 times with PBS then diluted in BTXpress high performance electroporation solution (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) to a final density of 2–10 X106 cells/ml for mobilized blood CD34+ HSPCs or 107 cells/ml for fetal liver CD34+ HSPCs. This cell suspension was mixed with 40μg/ml, or the indicated amount, of in vitro transcribed ZFN mRNA and electroporated in a BTX ECM830 Square Wave electroporator (Harvard Apparatus) in a 2mm cuvette using a single pulse of 250V for 5ms. Post-electroporation, fetal liver–derived cells were cultured in fetal liver CD34 maintenance media, while mobilized blood HSPCs were cultured in mobilized blood CD34 maintenance media plus 20ng/ml IL-6 (PeproTech), unless indicated.

Analysis of genome modification

For experiments using GFP donors, cells were collected at different time points post-treatment and analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry, using either a BD FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), or Guava EasyCyte 6-2L or EasyCyte 5HT (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Data acquired was analyzed using FlowJo software version 9.5.3 or version X (Treestar, Ashland, OR), or InCyte version 2.5 (EMD Millipore). In each independent analysis, GFP+ populations of cells were defined using gates assigned using untreated or mock treated populations cultured in parallel, with the criteria that 0.1% or less of the cells from the untreated or mock treated populations would be included in the GFP+ gate.

In addition, a semi-quantitative In-Out PCR was used to measure the rates of GFP integration at the CCR5 locus. The assay uses two simultaneous PCR reactions. One primer pair amplifies HDR-mediated insertion events because one primer recognizes a sequence contained in the AAV vector, while the other binds only to a genomic sequence outside of this donor. Specifically, one primer binds within the poly A region of the GFP cassette and the other binds to a sequence 3′ (beyond) the end of the right CCR5 homology arm (Supplemental Table 4, CCR5 In-Out primers). This PCR product, designated CCR5-HDR, was normalized by comparison to the product resulting from a control primer set (Ctrl.) which recognizes sequences in the CCR5 locus that are not included in the homology donor (Supplemental Table 4, CCR5 control primers). The concentration of the In-Out primer set was 2 times that of the control primer set, to increase detection sensitivity. The relative intensities of each CCR5-HDR PCR product were normalized for DNA input and quantitated by comparison to a set of standards, generated from genomic DNA isolated from a K562 cell line with a constant level of GFP integration at the CCR5 locus, as quantitated by Southern blot. A similar PCR reaction was used to detect site-specific integration of the GFP cassette at AAVS1, using specific primers sets (Supplemental Table 4, AAVS1 In-Out and control primers), and standardization against a K562 cell clone with a single GFP integrant at one of the AAVS1 loci.

For experiments using RFLP donors, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assays and Illumina deep sequencing were used to quantify the frequency of genome modification. The RFLP assay was performed as described64, with some modifications. Briefly, a pair of CCR5 or AAVS1 out-out primers (Supplementary Table 2, out-out1), located outside the region of homology contained within the CCR5 or AAVS1 donor molecules, was used for PCR amplification. The PCR products were then digested with XhoI (CCR5) or HindIII (AAVS1) and resolved on 1% agarose or 10% polyacrylamide gels. Alternatively, for CCR5, the gel-purified out-out PCR product was re-amplified using CCR5 in-in primers (Supplemental Table 4) before XhoI digestion. For llumina deep sequencing, gel-purified PCR products were amplified with a target-specific Miseq adaptor primer pair (Supplemental Table 4, adaptor primers) and sequence barcodes were added in the subsequent PCR reaction using the barcode primer pairs. Alternatively, 1/5000 of the PCR products amplified using primer pair out-out1 were re-amplified with primer pair out-out2 (Supplemental Table 4), then 1/5000 of the second PCR products were amplified using the Miseq adaptor primers. The final PCR products were cleaned and sequenced in an Illumina Miseq sequencer, essentially as described by the manufacturer (Illumina, San Diego, CA). For analysis of genome modification levels, a custom-written computer script was used to merge paired-end 150bp sequences, and adapter trimmed via SeqPrep (John St. John, https://github.com/jstjohn/SeqPrep, unpublished). Reads were aligned to the wild-type template sequence. Merged reads were filtered using the following criteria: the 5′ and 3′ ends (23bp) must match the expected amplicon exactly, the read must not map to a different locus in the target genome as determined by Bowtie266 with default settings, and deletions must be <70% of the amplicon size or <70bp long. Indel events in aligned sequences were defined as described previously35, with the exceptions that indels of 1bp in length were also considered true indels to avoid undercounting real events, and true indels must include deletions occurring within the sequence spanning between the penultimate bases (adjacent to the gap) of the binding site for each partner ZFN. Events with expected RFLP modification were defined based on perfect alignment with the DNA sequence containing the novel restriction site (CCR5 RFLP: AGTTTGTCTCGAGGTGATGA; AAVS1 RFLP: AGTGGGGCAAGCTTTACTAGGG) of the expected sequences.

Colony forming unit and cell growth assays

Cells were cultured in X-Vivo 10 media with 100 ng/ml each of SCF, Flt3 ligand, and TPO, and 10ng/ml interleukin (IL)-6 (PeproTech). To monitor cell growth, cells were collected at indicated time points for cell counting by flow cytometry (Guava EasyCyte 5HT) after addition of 5μg/ml propidium iodide (PI), to exclude dead cells, and flow count beads (Beckman Coulter) for reference.

For colony formation assays, cells were plated as a single-cell suspension at a density of 200–800 cells/ml in semi-solid methylcellulose-based medium containing 50 ng/ml SCF, 20 ng/ml GM-CSF, 20 ng/ml IL-3, 10 ng/ml IL-6, 20ng/ml G-CSF, and 3 units/ml erythropoietin (EPO) (StemCell Technologies Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada), at 24 hours post-electroporation 36. After 2 weeks of incubation, CFUs were classified and enumerated by trained operators on the basis of size and morphological characterization under a light microscope. Individual CFUs were then picked into 50μl QuickExtract DNA extraction solution (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). DNA was extracted from colonies and subjected to deep sequencing analysis as described above. Colonies with 2 or more sequences comprising >10% of reads were treated as mixed clones and excluded from final genotyping analysis. Unique sequences comprising < 10% of total sequence reads for a given sample were considered to be the result of processing errors and/or sample contamination and were also excluded from the analysis. Individual CFUs were identified as wt/wt (CFU count: a), wt/indel (b), wt/RFLP (c), indel/RFLP (d), indel/indel (e), and RFLP/RFLP (f). Frequency of RFLP modification in the population was then calculated using the following: % RFLP = (c+d+2f)/(2a+2b+2c+2d+2e+2f)*100%.

HSPC subset analysis

Mobilized blood or fetal liver–derived CD34+ HSPCs were treated with AAV6 vectors and ZFN mRNA as described above. One or two days post-mRNA electroporation, cells were washed, blocked in FCS (Denville), and stained with the following fluorophore conjugated antibodies: CD34 (581) (BD Biosciences), CD90 (5E10) (BD Biosciences), and CD133/2 (293C3) (Miltenyi Biotec). Cell sorting into subsets based on expression of these markers was performed using a BD FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences), with all compensations performed using Diva software (BD Biosciences). Subsets were defined as primitive (P; CD34+CD133+CD90+), early (E; CD34+CD133+CD90−), and committed (C; CD34+CD133−CD90−) progenitors23. The subsets derived from fetal liver HSPCs were cultured in fetal liver maintenance media, and the subsets derived from mobilized blood HSPCs were maintained in SFEM-II media (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) supplemented with SCF, Flt3L, TPO, and IL-6, for a further 6–7 days. GFP expression was determined in each population by flow cytometry, and site-specific insertion of GFP at either the CCR5 or AAVS1 loci was analyzed by In-Out PCR, as described above.

Mouse engraftment and human cell analysis

Fetal liver HSPC engraftment of 1 to 2 day old NOD.Cg-Prkcdscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) neonatal mice was performed as previously described, using 1 × 106 CD34+ cells per mouse47. No preference was given to any animal property at the time of engraftment and mice were randomly assigned to each engraftment group. Two separate litters of mice were engrafted with HSPCs from each fetal liver donor to limit possible litter effects on results. Peripheral blood (70μl) was sampled every 4 weeks from 8 weeks of age, and spleen and bone marrow were isolated at necropsy, as described47. Whole blood and tissue samples were blocked in FCS (Denville) and stained with the following antibody-fluorophore conjugates: CD4-V450 (RPA-T4), CD3-PE (UCHT1), CD19-APC (HIB19), and CD45-PerCP (TUI16) (BD Biosciences) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Red blood cells were lysed after staining by incubation in BD Pharm Lyse buffer (BD Biosciences), lysis was halted by the addition of PBS, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences). Compensation samples were created with BD CompBeads (BD Biosciences). Analysis of flow cytometry data was performed using FlowJo software version 9.5.3 or version X (Treestar, Ashland, OR). Compensation for stain overlap was performed post-acquisition using the tools included in FlowJo software. Initial gating was performed as forward scatter height versus forward scatter area to obtain the single cell population; the resulting population was plotted on a side scatter area versus forward scatter area grid to gate for live lymphocyte populations. Subsequent gates were set using full minus one controls such that less than 0.1% of cells not receiving a specific stain were considered positive for that stain. There was no operator blinding in the analyses. Secondary transplantations were performed using 1 × 107 mouse bone marrow cells harvested from the upper and lower limbs of two separate mice for each condition (CCR5-RFLP/ZFN and CCR5-GFP/ZFN). Each pooled bone marrow sample contained 10% human CD45+CD34+ cells, and was transplanted into 8 week old female NSG mice, as described47.

For experiments using mobilized blood HSPCs, adult (7 week old) female NSG mice were engrafted by retro-orbital injection of 1 × 106 cells, as described36. Twenty weeks later, bone marrow was harvested and analyzed for human CD45+ cells, as described above.

Mouse blood and tissue samples were also subjected to genomic DNA purification using NucleoSpin Tissue XS kits (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, PA) and subsequent molecular analysis as described above. All animal studies were performed in compliance with the regulations and with the approval of the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the software suite GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) or the Excel Analysis ToolPak. Off-target data analysis used the method described by Guilinger et al67, with Bonferroni-correction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the California HIV/AIDS Research Program ID12-USC-245 and F10-USC-207, US National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL73104, R01 DE025167, and U19 HL129902, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine grant RT3-07848, and the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust. We thank L. Truong, G. Lee, and Y. Lee for CD34+ cells, E. Lopez, E. Seclen and J. Rathbun for assistance with humanized mice, E. Killingbeck and P. Cheung for MiSeq analysis, A. Goodwin, A. Kang, and H. Tran for AAV production, A. Reik and F. Urnov for AAVS1 ZFNs, C. Wang for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.W., C.M.E. and J.J.D. performed most of the experiments; S.B.H., P.W.L., D.A.S., R.T.S. and G.N.L. developed assays and analyzed samples; J.W., C.M.E., P.D.G., M.C.H. and P.M.C. designed the experiments and analyzed data; J.W., C.M.E, M.C.H. and P.M.C. wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The following authors are full-time employees of Sangamo BioSciences, Inc.; J.W., J.J.D., S.B.H., P.W.L., D.A.S., R.T.S., P.D.G and M.C.H.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper

References

- 1.Aiuti A, et al. Correction of ADA-SCID by Stem Cell Gene Therapy Combined with Nonmyeloablative Conditioning. Science. 2002;296:2410–2413. doi: 10.1126/science.1070104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartier N, et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy with a Lentiviral Vector in X-Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326:818–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biffi A, et al. Lentiviral Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy Benefits Metachromatic Leukodystrophy. Science. 2013:341. doi: 10.1126/science.1233158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiuti A, et al. Lentiviral Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy in Patients with Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome. Science. 2013:341. doi: 10.1126/science.1233151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavazza A, Moiani A, Mavilio F. Mechanisms of Retroviral Integration and Mutagenesis. Human Gene Therapy. 2013;24:119–131. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun CJ, et al. Gene Therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome—Long-Term Efficacy and Genotoxicity. Science Translational Medicine. 2014;6:227ra233. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, et al. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118:3132–3142. doi: 10.1172/JCI35700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF., 3rd ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends in biotechnology. 2013;31:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung P, Klein H. Mechanism of homologous recombination: mediators and helicases take on regulatory functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:739–750. doi: 10.1038/nrm2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyman C, Kanaar R. DNA double-strand break repair: all’s well that ends well. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:363–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brugmans L, Kanaar R, Essers J. Analysis of DNA double-strand break repair pathways in mice. Mutat Res. 2007;614:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kowalczykowski SC. Initiation of genetic recombination and recombination-dependent replication. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:156–165. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01569-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urnov FD, Rebar EJ, Holmes MC, Zhang HS, Gregory PD. Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:636–646. doi: 10.1038/nrg2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tebas P, et al. Gene Editing of CCR5 in Autologous CD4 T Cells of Persons Infected with HIV. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:901–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, et al. Corepressor-dependent silencing of fetal hemoglobin expression by BCL11A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:6518–6523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303976110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lombardo A, et al. Site-specific integration and tailoring of cassette design for sustainable gene transfer. Nat Meth. 2011;8:861–869. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coluccio A, et al. Targeted Gene Addition in Human Epithelial Stem Cells by Zinc-finger Nuclease-mediated Homologous Recombination. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1695–1704. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer M, de Angelis MH, Wurst W, Kühn R. Gene targeting by homologous recombination in mouse zygotes mediated by zinc-finger nucleases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:15022–15026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009424107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pei Y, et al. A platform for rapid generation of single and multiplexed reporters in human iPSC lines. Sci Rep. 2015:5. doi: 10.1038/srep09205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lombardo A, et al. Gene editing in human stem cells using zinc finger nucleases and integrase-defective lentiviral vector delivery. Nat Biotech. 2007;25:1298–1306. doi: 10.1038/nbt1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genovese P, et al. Targeted genome editing in human repopulating haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;510:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature13420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baum CM, Weissman IL, Tsukamoto AS, Buckle AM, Peault B. Isolation of a candidate human hematopoietic stem-cell population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992;89:2804–2808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doulatov S, Notta F, Laurenti E, Dick John E. Hematopoiesis: A Human Perspective. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoban MD, et al. Correction of the sickle-cell disease mutation in human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 2015;125:2597–2604. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song L, et al. Optimizing the transduction efficiency of capsid-modified AAV6 serotype vectors in primary human hematopoietic stem cells in vitro and in a xenograft mouse model in vivo. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:986–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song L, et al. High-Efficiency Transduction of Primary Human Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Erythroid Lineage-Restricted Expression by Optimized AAV6 Serotype Vectors In Vitro and in a Murine Xenograft Model In Vivo. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veldwijk MR, et al. Pseudotyped recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors mediate efficient gene transfer into primary human CD34(+) peripheral blood progenitor cells. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:107–112. doi: 10.3109/14653240903348293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez EE, et al. Establishment of HIV-1 resistance in CD4+ T cells by genome editing using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:808–816. doi: 10.1038/nbt1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moehle EA, et al. Targeted gene addition into a specified location in the human genome using designed zinc finger nucleases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:3055–3060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen F, et al. High-frequency genome editing using ssDNA oligonucleotides with zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Meth. 2011;8:753–755. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim H, Kim JS. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:321–334. doi: 10.1038/nrg3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller JC, et al. An improved zinc-finger nuclease architecture for highly specific genome editing. Nat Biotech. 2007;25:778–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller JC, et al. Improved specificity of TALE-based genome editing using an expanded RVD repertoire. Nat Meth. 2015;12:465–471. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ran FA, et al. Double Nicking by RNA-Guided CRISPR Cas9 for Enhanced Genome Editing Specificity. Cell. 154:1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabriel R, et al. An unbiased genome-wide analysis of zinc-finger nuclease specificity. Nat Biotech. 2011;29:816–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, et al. Genomic Editing of the HIV-1 Coreceptor CCR5 in Adult Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells Using Zinc Finger Nucleases. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1259–1269. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung AK, Hoggan MD, Hauswirth WW, Berns KI. Integration of the adeno-associated virus genome into cellular DNA in latently infected human Detroit 6 cells. Journal of Virology. 1980;33:739–748. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.2.739-748.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith JR, et al. Robust, Persistent Transgene Expression in Human Embryonic Stem Cells Is Achieved with AAVS1-Targeted Integration. STEM CELLS. 2008;26:496–504. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller DG, Petek LM, Russell DW. Adeno-associated virus vectors integrate at chromosome breakage sites. Nat Genet. 2004;36:767–773. doi: 10.1038/ng1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin Y, Waldman AS. Promiscuous patching of broken chromosomes in mammalian cells with extrachromosomal DNA. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:3975–3981. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.19.3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin Y, Waldman AS. Capture of DNA Sequences at Double-Strand Breaks in Mammalian Chromosomes. Genetics. 2001;158:1665–1674. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.4.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray L, et al. Enrichment of human hematopoietic stem cell activity in the CD34+Thy− 1+Lin− subpopulation from mobilized peripheral blood. Blood. 1995;85:368–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Majeti R, Park CY, Weissman IL. Identification of a Hierarchy of Multipotent Hematopoietic Progenitors in Human Cord Blood. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Negrin RS, et al. Transplantation of highly purified CD34+Thy-1+ hematopoietic stem cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplant. 2000;6:262–271. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vose JM, et al. Transplantation of highly purified CD34+Thy-1+ hematopoietic stem cells in patients with recurrent indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:680–687. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11787531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dick JE, Bhatia M, Gan O, Kapp U, Wang JCY. Assay of human stem cells by repopulation of NOD/SCID mice. STEM CELLS. 1997;15:199–207. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530150826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holt N, et al. Human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells modified by zinc-finger nucleases targeted to CCR5 control HIV-1 in vivo. Nat Biotech. 2010;28:839–847. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hogan CJ, Shpall EJ, Keller G. Differential long-term and multilineage engraftment potential from subfractions of human CD34+ cord blood cells transplanted into NOD/SCID mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:413–418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012336799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dick JE, Guenechea G, Gan OI, Dorrell C. In Vivo Dynamics of Human Stem Cell Repopulation in NOD/SCID Mice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;938:184–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKenzie JL, Gan OI, Doedens M, Wang JCY, Dick JE. Individual stem cells with highly variable proliferation and self-renewal properties comprise the human hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1225–1233. doi: 10.1038/ni1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gu A, et al. Engraftment and Lineage Potential of Adult Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells Is Compromised Following Short-Term Culture in the Presence of an Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Antagonist. Human Gene Therapy Methods. 2014;25:221–231. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2014.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hofer U, et al. Pre-clinical Modeling of CCR5 Knockout in Human Hematopoietic Stem Cells by Zinc Finger Nucleases Using Humanized Mice. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;208:S160–S164. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Notta F, et al. Isolation of Single Human Hematopoietic Stem Cells Capable of Long-Term Multilineage Engraftment. Science. 2011;333:218–221. doi: 10.1126/science.1201219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hirata R, Chamberlain J, Dong R, Russell DW. Targeted transgene insertion into human chromosomes by adeno-associated virus vectors. Nat Biotech. 2002;20:735–738. doi: 10.1038/nbt0702-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller DG, et al. Gene targeting in vivo by adeno-associated virus vectors. Nat Biotech. 2006;24:1022–1026. doi: 10.1038/nbt1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russell DW, Hirata RK. Human gene targeting by viral vectors. Nat Genet. 1998;18:325–330. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rogers CS, et al. Production of CFTR-null and CFTR-ΔF508 heterozygous pigs by adeno-associated virus–mediated gene targeting and somatic cell nuclear transfer. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118:1571–1577. doi: 10.1172/JCI34773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirsch ML. Adeno-associated virus inverted terminal repeats stimulate gene editing. Gene Ther. 2015;22:190–195. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barzel A, et al. Promoterless gene targeting without nucleases ameliorates haemophilia B in mice. Nature. 2015;517:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature13864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeKelver RC, et al. Functional genomics, proteomics, and regulatory DNA analysis in isogenic settings using zinc finger nuclease-driven transgenesis into a safe harbor locus in the human genome. Genome Research. 2010;20:1133–1142. doi: 10.1101/gr.106773.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doyon Y, et al. Enhancing zinc-finger-nuclease activity with improved obligate heterodimeric architectures. Nat Meth. 2011;8:74–79. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boczkowski D, Nair SK, Nam JH, Lyerly HK, Gilboa E. Induction of Tumor Immunity and Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Responses Using Dendritic Cells Transfected with Messenger RNA Amplified from Tumor Cells. Cancer Research. 2000;60:1028–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang J, et al. Targeted gene addition to a predetermined site in the human genome using a ZFN-based nicking enzyme. Genome Research. 2012;22:1316–1326. doi: 10.1101/gr.122879.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xiao X, Li J, Samulski RJ. Production of High-Titer Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors in the Absence of Helper Adenovirus. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:2224–2232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2224-2232.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Meth. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guilinger JP, et al. Broad specificity profiling of TALENs results in engineered nucleases with improved DNA-cleavage specificity. Nat Meth. 2014;11:429–435. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.