Abstract

Ephrin-A5, a ligand of the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases, plays a key role in lens fiber cell packing and cell-cell adhesion, with approximately 87% of ephrin-A5−/− mice develop nuclear cataracts. Here, we investigated the extensive formation of light-scattering globules associated with breakdown of interlocking protrusions during lens opacification in ephrin-A5−/− mice. Lenses from wild-type (WT) and ephrin-A5−/− mice between 2–21 weeks old were studied with light and electron microscopy, immunofluorescence labeling, freeze-fracture TEM and filipin cytochemistry for membrane cholesterol detection. Lens opacities with various densities were first observed in ephrin-A5−/− mice at around 60 days old. Dense cataracts in the mutant lenses were seen primarily in the nuclear region surrounded by transparent cortices from all eyes examined. We confirmed that a majority of nuclear cataracts were dislocated posteriorly and ruptured the thinner posterior lens capsule. SEM analysis indicated that numerous interlocking protrusions and wavy ridge-and-valley membrane surfaces in deep cortical and nuclear fibers did not cause lens opacity in both transparent ephrin-A5−/− and WT mice. In contrast, abundant isolated membranous globules of approximately 1,000 nm in size were distributed randomly along the intact fiber cells during early stage of all ephrin-A5−/− cataracts examined. A further examination using both SEM and TEM revealed that isolated globules were generated from the disintegrated interlocking protrusions originally located along the corners of hexagonal fiber cells. Freeze-fracture TEM further revealed the association of square-array aquaporin junctions with both isolated globules and interlocking membrane domains. This study reports for the first time that disrupted interlocking protrusions are the source of numerous large membranous globules that contribute to light scattering and nuclear cataracts in the ephrin-A5−/− mice. Our results further suggest that dissociations of N-cadherin and adherens junctions in the associated interlocking domains may result in the formation of isolated globules and nuclear opacities in the ephrin-A5−/− mice.

1. Introduction

The integrity of fiber cells depends on the normal and extensive distributions of its unique interlocking system (Cohen, 1965; Dickson and Crock, 1972; Kuwabara, 1975; Kuszak et al., 1980; Willekens and Vrensen, 1982; Kistler et al., 1986; Zhou and Lo, 2003; Lo et al., 2014) and adherens junctions (Volk and Geiger, 1986; Geiger et al., 1987; Lo, 1988; Atreya et al., 1989; Maisel and Atreya, 1990; Lo et al., 2000; Bagchi et al., 2002; Straub et al., 2003) within the lens. It has been previously suggested that the interlocking protrusions may assist in an overall stability of fiber-cells at the gross level, while adherens junctions maintain localized adhesions in protrusions and between fiber cells at the microscopic level (Lo, 1988; Lo and Reese, 1993; Zhou and Lo, 2003).

Molecular signaling plays critical functions in maintaining the precise cytoarchitecture of the lens. One such example is the Eph family of tyrosine kinases, which has been found to play critical roles in lens biology (Son et al., 2012). Ephrin-A5, a ligand within this class of signaling molecules, has been previously identified to have an essential role in lens fiber cell packing and cell-cell adhesion (Cooper et al., 2008; Son et al., 2012; Son et al., 2013). Previous research had found that ephrin-A5−/− mice exhibit cataracts (Cooper et al., 2008; Son et al., 2012; Son et al., 2013). In addition, ephrin-A5 has been previously found to play integral roles in the maintenance of the adherens junction, as ephrin-A5−/− mice displayed disruptions in N-cadherin localization and its interactions with β-catenin (Cooper et al., 2008). However, the precise nature and mechanics underlying the cataractogenesis observed in ephrin-A5−/− mice remains to be elucidated.

This current study reveals that the ephrin-A5−/− lens displays a unique nuclear cataract which shows formation of extensive large globules which are possibly originated from the breakdown of interlocking protrusions during nuclear cataract formation in the absence of ephrin-A5. The present study further demonstrates that N-cadherin and associated adherens junctions are highly enriched in interlocking protrusions in fiber cells of the wild-type (WT) mice. The disruption of N-cadherin-beta-catenin complex may cause the dissolution of adherens junctions in ephrin-A5−/− lenses. As a result, it may facilitate the breakdown and separation of adherens junction-associated interlocking protrusions to form numerous membranous globules which are large enough to cause lens opacification in ephrin-A5−/− lenses.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and lens transparency photography

Freshly enucleated eyes of wild-type (WT) and ephrin-A5−/− mice of both genders at age 2–21 weeks were collected in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum culture medium. Each pairs of the lenses were removed, immersed in the medium or PBS at RT, examined and documented for lens transparency under a dissecting microscopy system (Nikon SMZ800, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a lens collecting glass (painted black) and a digital camera (Nikon Coolpix5000, Tokyo, Japan) modified from the original design by Kuck (Kuck et al., 1981). This modified microscopy system was enhanced with a high resolution objective lens and better light source (FS1000 Micro-Lite fluorescent electronic ring illuminator with new glare free “full spectrum” FS150 bulb, TEquipment.net, Long Branch, NJ) for capturing contrasted images. Lenses were then fixed immediately for the various experiments described below. Our early studies have examined the effects of BFSP2 (CP49/phakinin) mutation on ephrin-A5−/− cataract formation and found no additional contribution by this mutation (Son et al., 2013). The animals were treated in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Resolution on the Use of Animals in Research.

2.2. Histology and thin-section electron microscopy

Freshly isolated lenses from WT and ephrin-A5−/− mice at various ages were fixed in an improved fixative containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3), 50 mM L-lysine and 1% tannic acid for 2 h at room temperature (Lo, 1988). Each lens was mounted on a specimen holder with superglue and cut into 200 μm slices with a Vibratome. Alternatively, after fixation the “whole-mount” preparations of lens fibers were processed for thin-section TEM to facilitate visualizations of a more favorable distribution of adherens junctions in interlocking protrusions (see method below in immunofluorescence labeling). Tissue slices or lens quarters were then postfixed in 1% aqueous OsO4 for 1 h at room temperature, rinsed in distilled water, and stained en bloc with 0.5% uranyl acetate in 0.15 M NaCl overnight at 4°C. Lens tissues were dehydrated through graded ethanol and propylene oxide, and then embedded in Polybed 812 resin (EMS, Hatfield, PA). Thick sections (1 μm) cut with a diamond knife were stained with 1% toluidine blue and examined with a Zeiss light microscope equipped with a digital camera. Some eye and lens tissues were processed for paraffin thick sections (5 μm) and labeled with H+E staining as previously described (Cooper et al., 2008). Thin sections (80 nm) were cut with a diamond knife, stained with 5% uranyl acetate followed by Reynold’s lead citrate and examined in a JEOL 1200EX electron microscope at 80 kV (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

2.3. Scanning electron microscopy

To observe interlocking protrusions along the narrow-sides of elongated fiber cells, freshly isolated lenses of wild-type and ephrin-A5−/− mice at various ages were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3 at room temperature for 48–72 h. Each lens was properly orientated and fractured with a needle or sharp razor blade to expose the longitudinal configuration of narrow-side fiber cells at the anterior, equatorial and posterior regions of the lens. Lens halves were then postfixed in 1% aqueous OsO4 for 1–2 h at room temperature, dehydrated in graded ethanol and dried in a Samdri-795 critical point dryer (Tousimis Inc., Rockville, MD). Lens halves were mounted on specimen stubs and coated with gold/palladium in a Hummer VII sputter coater (Anatech Inc., Union City, CA). Micrographs were taken with a JEOL 820 scanning electron microscope at 10 kV (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). In addition, we also used “whole mount” preparations to observe interlocking protrusions along the broad sides of elongated cortical fiber cells (Lo et al., 2014).

2.4. Freeze-fracture TEM and cytochemical detection of membrane cholesterol

Freshly isolated lenses of WT and ephrin-A5−/− mice were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) at RT for 2–4 h. After washing in buffer, lenses were orientated to obtain sagittal (longitudinal) sections with a Vibratome, after which slices were collected, marked serially from superficial to deep, and kept separately. The slices were then cryoprotected with 25% glycerol in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer at RT for 1 h and processed for freeze-fracture TEM according to our routine procedures (Biswas et al., 2009). In brief, a single lens slice was mounted on a gold specimen carrier and frozen rapidly in liquefied Freon 22 and stored in liquid nitrogen. Cryofractures of frozen slices were made in a modified Balzers 400T freeze-fracture unit, at a stage temperature of −135°C in a vacuum of approximately 2 × 10−7 Torr. The lens tissue was fractured by scraping a steel knife across its frozen surface to expose fiber cell membranes. The fractured surface was then immediately replicated with platinum (~2 nm thick) followed by carbon film (~25 nm thick). The replicas, obtained by unidirectional shadowing at 45°, were cleaned with household bleach and examined with a JEOL 1200EX TEM. For cytochemical detection of filipin-cholesterol-complexes (FCCs) with freeze-fracture TEM, we followed the same procedures as described previously (Biswas et al., 2009; Biswas et al., 2010).

2.5. Immunofluorescence labeling

For immunofluorescence labeling, postnatal wild-type and ephrin-A5−/− eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% formaldehyde in 1× PBS (pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C, rinsed in 1× PBS for 5 min, and stored in 10% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4 °C. Alternatively, they were washed for 2 × 30 min in PBS, infiltrated in 0.6 M sucrose-PBS for overnight at 4 °C, and transferred to 1.15 M sucrose-PBS for second overnight at 4 °C. Lenses were then embedded in OCT in plastic embedding molds for 2 h at RT and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Thick sections (10 or 20 μm thick) were cut with a cryostat at 20 °C. Sections containing cortical and nuclear fibers were collected with ambient-temperature glass slides and stored in an 80 °C freezer. The slides were later transferred to a 20 °C freezer for overnight before use (Biswas et al., 2014a). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by detection using goat or donkey secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) or CY3 (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 2 h at room temperature. Lens tissue was stained using antibodies against EphA2 (1:200; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), β-catenin (1:3000; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and N-cadherin (1:200; Development Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA). Cell membranes were observed using Wheat Germ Agglutinin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 (5 μg/ml, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY).

Whole mount preparations were also performed to observe broad-side views of cortical fiber cells (Lo et al., 2014). In brief, the freshly isolated lenses were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (EMS, Hatfield, PA) in PBS for 2 h at RT. Each lens was first cut into quarters with a double-edge razor blade along the anterior to posterior axis. Within each quarter, the lens nucleus was removed with tweezers, and the remaining successive layers of cortical fibers were gradually peeled away until the desired approximate layers of cells were achieved as determined by degrees of transparency under a dissecting microscope with a bottom light source. For N-cadherin antibody labeling, fiber cells of lens quarters in slightly different layers were incubated in 2% BSA-PBS solution for 1 h at RT to block non-specific binding, and then incubated with an affinity purified rabbit anti-human N-cadherin extracellular domain (aa 450–512) polyclonal antibody (H-63, sc-7939, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) at 1:100 dilutions in the blocking solution for 2 h at RT or overnight at 4°C. After washing (2 × 10 min) in PBS, fiber-cell whole mounts were incubated with FITC- conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG secondary antibody at 1:200 dilution (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at RT, rinsed in PBS and examined with a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope.

3. Results

3.1. Lens opacity in the deep cortex and nucleus of ephrin-A5−/− lenses

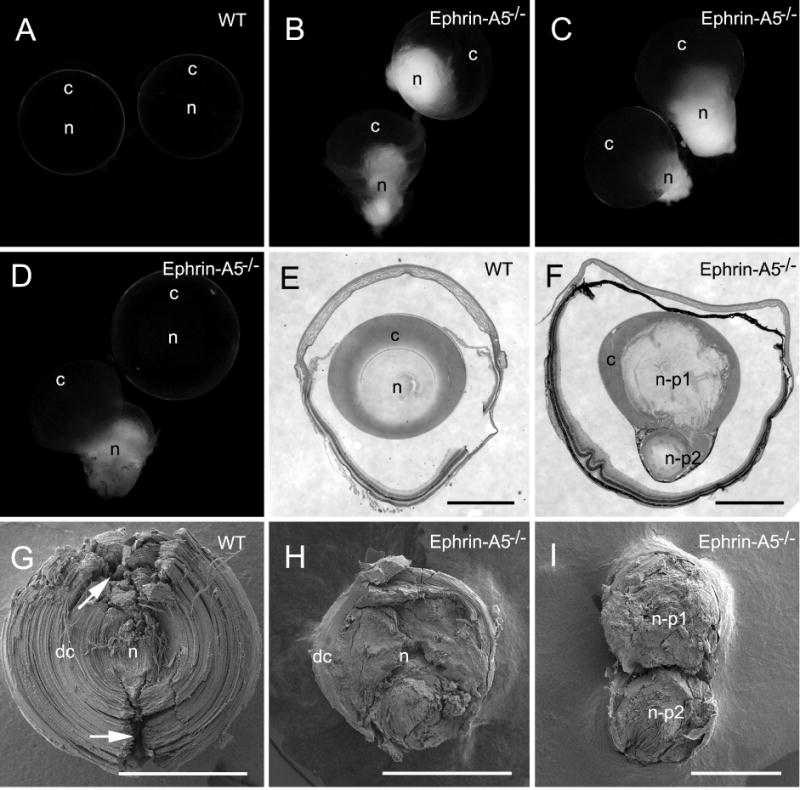

Lens opacities were primarily located in the nuclear regions in all cataractous lenses examined (Fig. 1B–D). Interestingly, the nuclear cataracts often disrupted their posterior lens capsules and were dislocated to the outside of the posterior lens surface (Fig. 1B–D). Also, occasionally, only one lens was found to display nuclear opacity (Fig. 1D) from a given pair of ephrin-A5−/− mice. In consistence with the observed dislocated lens opacity (Fig. 1B), histological examinations indeed revealed that dislocated nuclear cataracts were often divided into two parts (Fig. 1F). By taking advantage of this unique separation between cortical and nuclear fibers, the present study used both transparent outer cortical fibers and dislocated, cataractous deepcortical and nuclear fibers (Fig. 1H–I) for detailed investigations of the structural changes in relation to the possible causes of lens opacities in ephrin-A5−/− mice.

Fig. 1.

Representative photographs of lens transparency and correlated morphologies in pairs of wild-type and ephrin-A5−/− lenses examined. (A) A pair of lenses from a wild-type mouse at age 12 weeks, which are transparent in both cortex (c) and nucleus (n). B–D show dense opacities in the lens nucleus in both lens pairs (B–C) or in only one lens (D) of ephrin-A5−/− mice at age 8–12 weeks. Note that these nuclear cataracts generally ruptured and protruded out of the posterior lens capsule based on our overview of the eyeballs. E–F show histological comparison between the intact wild-type lens and ruptured ephrin-A5−/− lens, in which the breakdown of lens nucleus into two fragmented portions (n–p1 and n–p2) is shown. Also noted is the nuclear fragment (n–p2) protruded considerably toward the posterior lens capsule. G–I show SEM comparison of intact fibers in wild-type and ruptured ephrin-A5−/− lenses at low magnifications. The similarity in structural regularity is observable between intact cortical fibers and nuclear fibers of a wild-type lens (G) in which several artificial damaged regions (arrows) during tissue processing are also shown. In contrast, significant irregularities in arrangements of deep cortical (dc) and nuclear fibers (n) in ephrin-A5−/− lenses (H and I) are evident. Scale bars: E–I = 1000 μm.

3.2. Changes of intact interlocking protrusions into isolated membranous globules in deep cortex and nucleus of the lens during opacification in ephrin-A5−/− mice

Our initial SEM analysis revealed that the most dramatic changes in the ephrin-A5−/− lenses were the consistent formation of abundant isolated membranous globules in the deep cortical and nuclear fiber cells. We thus focused our investigations on the possible transformation between the breakdown of interlocking protrusions and the formation of numerous large globules in the absence of ephrin-A5 in the lens.

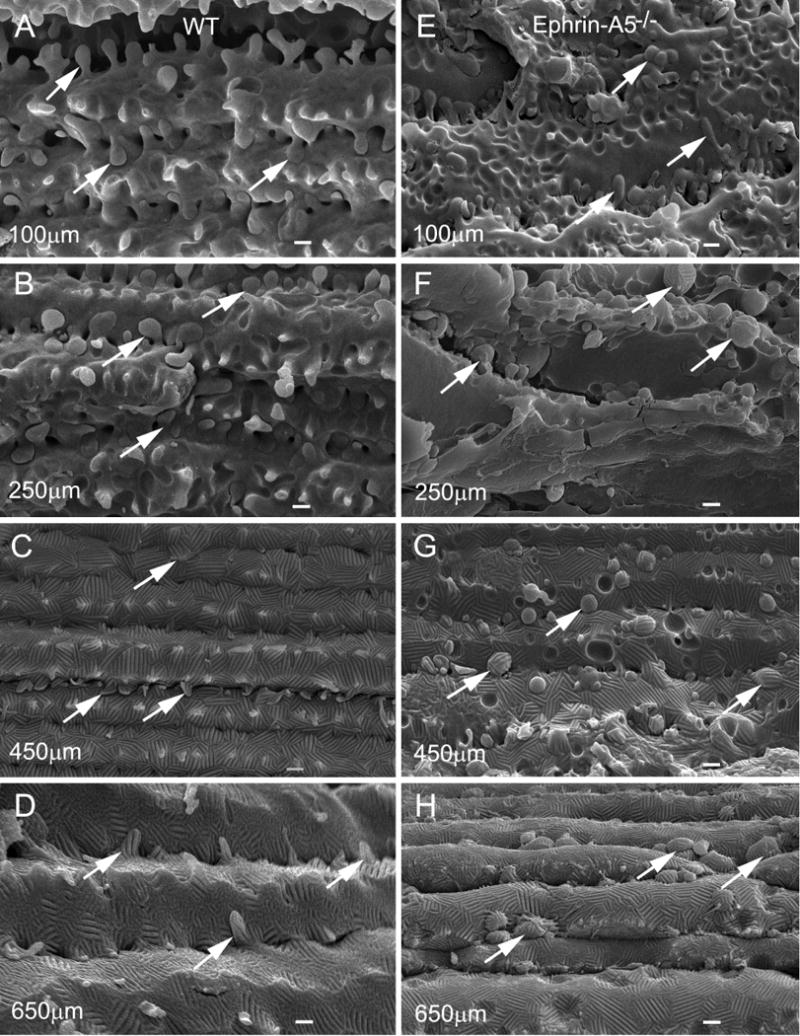

Systematic SEM examinations showed that in wild-type lenses all interlocking protrusions contained smooth surface of narrowed necks and expanded heads in superficial cortical fibers (Fig. 2A–B). They were gradually changed into wavy ridge-and-valley surface patterns in deeper cortical and nuclear fibers (Fig. 2C–D) with age. In addition, all protrusions were in elongated configurations even though they exhibited ridge-and-valley surface patterns (Fig. 2A–D). In contrast, except for those protrusions in superficial young fibers (Fig. 2E), they were gradually changed into round or oval shapes with distinct wavy ridge-and-valley surface patterns (Fig. 2F–H) in the ephrin-A5−/− lenses. Due to the significant shifts in the shapes and locations of protrusions, it was conceivable that the isolated protrusions or globules were most likely derived from the breakdown of interlocking protrusions during structural changes in the ephrin-A5−/− lenses (Fig. 2E–H). This was verified further with TEM analyses below.

Fig. 2.

SEM comparison of interlocking protrusions in specific regions of cortical and nuclear fibers in wild-type and ephrin-A5−/− mice. The protrusions of normal cortical fiber cells change gradually from the smooth surface in the superficial cortex (A) and outer cortex (B) to ridge-and-valley surface in the deep cortex and nucleus (C, D), approximately from 100 μm to 650 μm deep from the equatorial lens surface of lenses in wild-type mice at age 8 weeks. The ridge-and-valley surface patterns, which represent wavy square-array junctions of fiber cells, are first seen in the inner cortex (C), approximately 400 μm deep from the lens surface, and are found extended toward the nuclear region of the lens (D). E–H shows changes in membrane surface and shape of protrusions in cortical and nuclear fibers in ephrin-A5−/− lenses. In the ephrin-A5−/− lenses, protrusions basically still retain their smooth membrane surface and regular shape in slightly irregular superficial fiber cells (e.g., 100 μm deep) as compared with the age-matched wild-type lenses (E). However, the dramatic changes of interlocking protrusions are seen in deeper cortex and nucleus which include irregular shape, size increase, and wavy ridge-and-valley surface patterns (F–H). These changes usually begin in outer cortex (~ 250 μm deep) and are extended toward the deep cortical and nuclear regions (G–H). Based on the dramatic changes in their shape (from elongated to round) and the size increase, it is conceivable that many of these protrusions might become the isolated protrusions or membrane-bound globules that are separated from their intact fiber cells. Scale bars: A–H = 1 μm.

3.3. Different conversion stages from intact interlocking protrusions into isolated membranous globules

A detailed SEM analysis indicates that the distribution of round-shape protrusions was increased considerably in the deep cortex in ephrin-A5−/− lenses (Fig. 3A–B). These isolated protrusions exhibited both smooth and wavy ridge-and-valley surfaces (Fig. 3C–D), suggesting that they might be in different maturation stages. The wavy ridge-and-valley surfaces have previously been characterized to represent the unique square-array thin junction structures (Lo and Harding, 1984; Costello et al., 1985; Zampighi et al., 1989; Biswas et al., 2014b). Furthermore, thick-section light microscopy revealed that numerous intact or isolated globules of different densities were indeed largely distributed in disorganized nuclear fiber cells in ephrin-A5−/− lenses (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

SEM and light microscopy display a representative profile of interlocking protrusions and isolated membranous globules in damaged deep cortical fiber cells in ephrin-A5−/− mouse cataracts. A–D shows numerous round-shape protrusions or isolated globules of various sizes exhibiting either wavy ridge-and-valley surface pattern (arrows) or smooth surface (arrow heads). Light microscopy (E) shows distribution of numerous globules with different densities along the cell membranes, in the cytoplasm, or in the extracellular spaces. Scale bars: A–B = 10 μm; C–D = 1 μm; E = 30 μm.

3.4. Interlocking protrusion-derived membranous globules in the ephrin-A5−/− lens contain AQP0-dependent square arrays and abundant membrane cholesterols

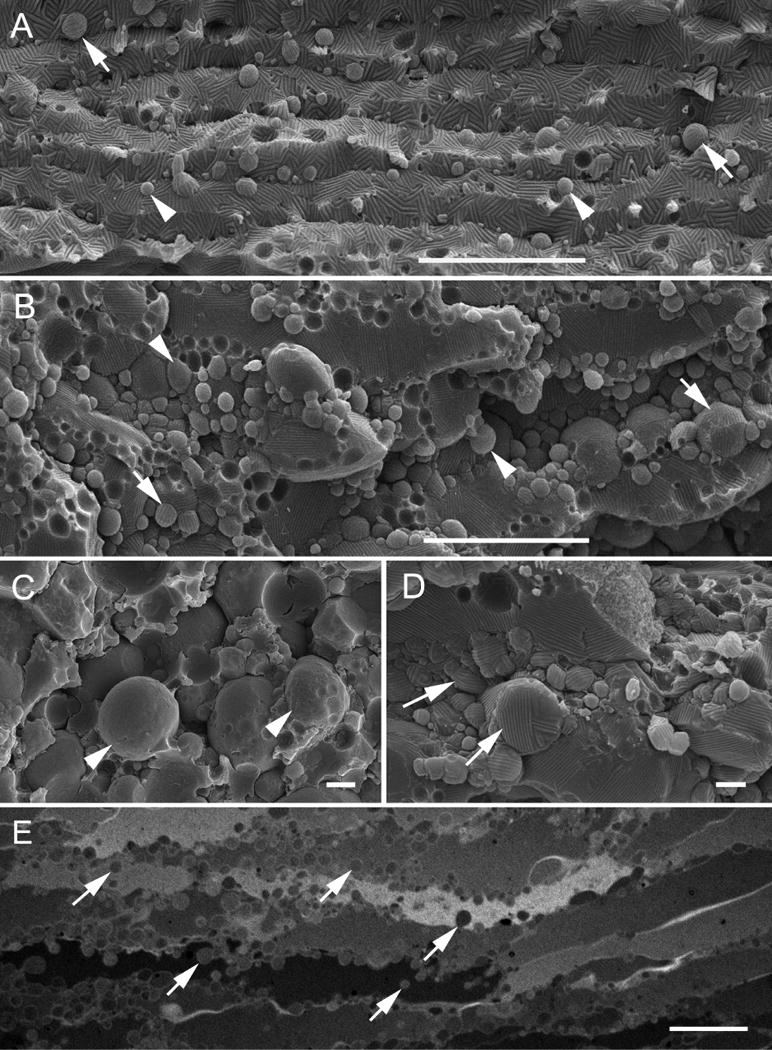

Freeze-fracture TEM was used to demonstrate that different membrane structures were found on the two types of isolate membranous globules which exhibited the smooth membrane surface vs. undulating ridge-and-valley surface. Figure 4A shows that isolate globules with smooth membrane surface contained the typical 8–9 nm intramembrane particles on the P-face of the membrane. These smooth-surface globules are believed to represent the early stage of isolate membrane globules due to their similar distribution of the typical 8–9 nm intramembrane particles seen in the intact smooth interlocking protrusions in superficial fibers (Biswas et al., 2010; Lo et al., 2014). In contrast, the isolated globules with ridge-and-valley surface patterns were shown to contain the same wavy ridge-and-valley patterns as those in the intact wavy protrusions distributed primarily in the deep cortical and nuclear fibers as shown with SEM in the wild-type (Fig. 2C–D) and with freeze-fracture TEM (Fig. 4B–C) in ephrin-A5−/− lenses. These wavy ridge-surface globules belong to the late mature stage of isolated globules due to their similar distributions of the ~6.5 nm square-array particle patterns. The specific association of unique wavy square arrays with ridge-and-valley membrane surface patterns seen in SEM and freeze-fracture TEM has been well documented (Lo and Harding, 1984; Costello et al., 1985; Zampighi et al., 1989; Biswas et al., 2014a; Biswas et al., 2014b). Furthermore, filipin cytochemistry in conjunction with freeze-fracture TEM revealed that isolated smooth globules were highly enriched with membrane cholesterols (represented by the filipin-cholesterol-complexes) (Fig. 4D) as those previously observed in the intact smooth protrusions (Biswas et al., 2010). In addition, as predicted, a number of isolate globules which contained patches of square-array junctions were significantly decreased or absent of filipin-cholesterol-complexes, in agreement with the previous findings for the AQP0-dependent square-array junctions (Biswas et al., 2014b).

Fig. 4.

Freeze-fracture TEM and filipin cytochemical analysis reveal the presence of intramembrane particles (proteins), square arrays and membrane cholesterol in isolated globules with either smooth or ridge-and-valley surface in ephrin-A5−/− lenses. Freeze-fracture TEM shows the presence of both e-face and p-face membranes on the same smooth globules (A), indicating that these globules are enclosed by double cell membranes. Note the 8–9 nm intramembrane particles are randomly distributed on the p-face of the membrane on the smooth globules (A). However, some isolated globules with undulating ridge-and-valley surfaces display different distribution patterns of intramembrane particles (B–C). They exhibit typical square-array configuration as those commonly seen in the deep cortical fibers (Biswas et al., 2014a; Biswas et al., 2014b). On these freeze-fracture surfaces, the p-face intramembrane particles of square arrays are generally distributed on the valley portion but not on the ridge portion (B and C). However, since the p-face square-array particles were often covered by the e-face membrane on the valley portion, these allowed only small rows of ~6.5 nm square-array particles along the sides of the valleys could sometime be observed (arrows). Filipin cytochemistry analysis reveals extensive distribution of membrane cholesterols (as represented by filipin-cholesterol-complexes, fcc) on both smooth and wavy isolated globules (D–F). However, the filipin-cholesterol-complexes are significantly decreased or absent in the patches of both flat (E) and wavy (F) square arrays (sa), due to the condensed localization of the square-array particles (Biswas et al., 2014b). Scale bars: A = 100 nm; B–F = 200 nm.

3.5. Adherens junction-associated interlocking protrusions and formation of isolated membranous globules

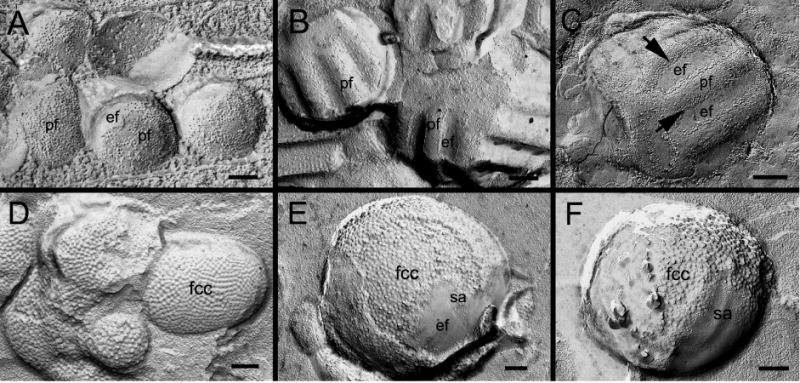

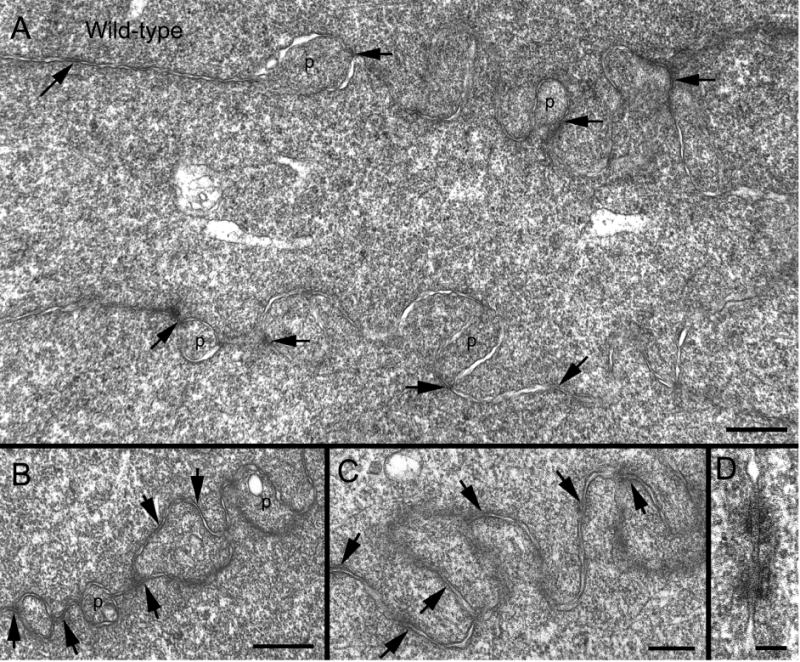

Since our previous study suggested that disruptions of N-cadherin and β-catenin adherens complex occurred in the ephrin-A5−/− lenses (Cooper et al., 2008), we hypothesize that the breakdown of interlocking protrusions may be directly associated with the loss of N-cadherin from the fiber cell membrane, and therefore adherens junctions, in the ephrin-A5−/− lenses. First, we apply thin-section TEM using an improved fixation (Lo, 1988; Lo et al., 2000) to establish the distribution of adherens junctions in interlocking protrusions in wild-type mouse lenses. Thin-section TEM showed that spotty (fascia) adherens junctions were indeed regularly located at the corners or along the entire length of interlocking protrusions in cortical fiber cells of various regions in wild-type lenses (Fig. 5A–C). High magnification shows that typical fascia adherens junctions with junctional plaques and cytoskeletal components were readily discernible between fiber cells as they were visualized in a more favorable sectional orientation (Fig. 5D). These new observations were greatly facilitated by using the “whole-mount” preparations to obtain a more favorable distribution of adherens junctions in interlocking protrusions for thin-section TEM (see Methods). The previous cross-sectional approaches have often resulted in visualizations of adherens junctions at the corners (apexes) and other non-protrusion regions of hexagonal fiber cells (Lo, 1988; Lo et al., 2000).

Fig. 5.

Thin-section TEM shows specific association of adherens junctions with interlocking protrusions in wild-type lenses. A low magnification overview of fiber cells reveals that adherens junctions (arrows) are regularly located at the corners of protrusions, or along the cell membranes near the apexes of fiber cells (A). B–C illustrates the specific localization of adherens junctions (arrows) associated with interlocking protrusions. High magnification reveals that intercellular adherens junctions are characterized as a spotty fascia-type (Lo, 1988; Lo et al., 2000) between lens fiber cells when they are clearly visualized under a favorable sectional orientation (D). Scale bars: A–B = 500 nm; C–D = 200 nm.

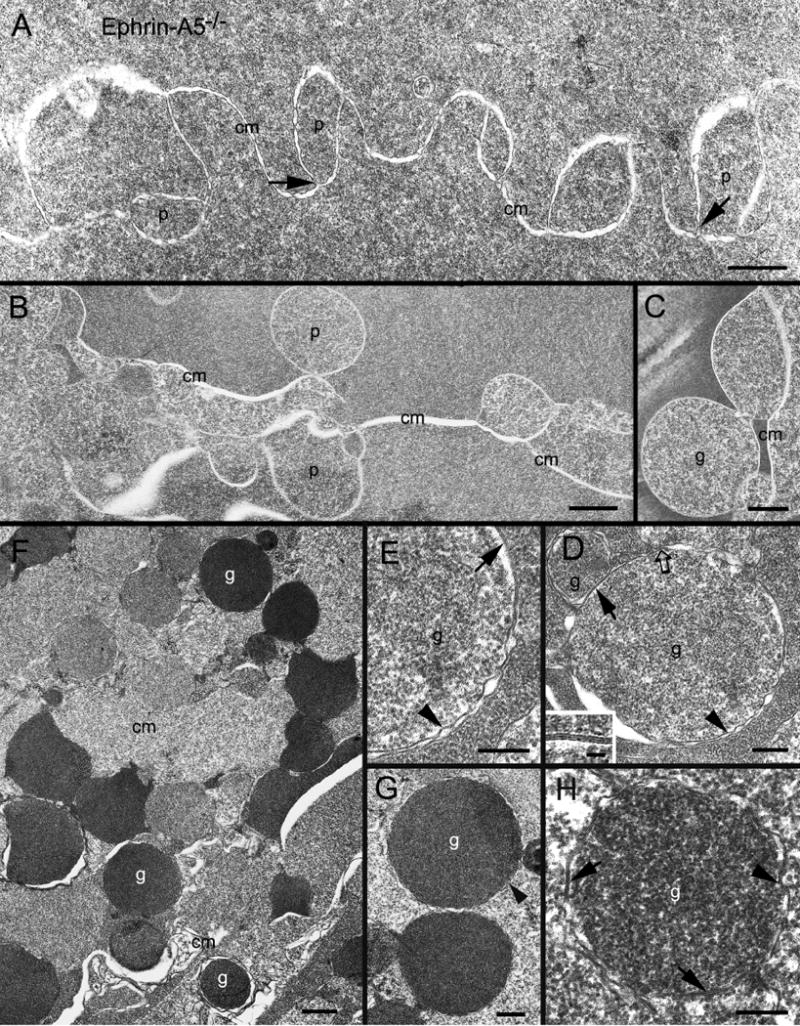

In ephrin-A5−/− lenses, interlocking protrusions were still retained their specific elongated shapes in superficial cortex, although the spotty adherens junctions were usually not distinctively visualized (Fig. 6A). In the slightly deeper cortex, in addition to significant disorganization of fiber cells, we revealed the intermediate stages during transformation and separation of intact interlocking protrusions into isolated round-shape globules with light electron density (Fig. 6B–C). These newly-formed globules were bounded by double cell membranes often exhibiting wavy configurations and 12–14 nm pentalaminar thin junctions (Fig. 6D–E). Moreover, numerous isolated globules with dark electron density, representing in their later stages, were also regularly distributed in the much deeper cortical and nuclear regions of the lenses (Fig. 6F). They were also enclosed by double cell membranes and frequently displayed wavy configurations and 12–14 nm thin-junctions (Fig. 6G–H). The above electron microscopic observations are consistent with the overview of numerous round-shape globules/protrusions seen in the histological preparations (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 6.

Thin-section TEM shows structural changes of interlocking protrusions and formation of membranous globules in ephrin-A5−/− lenses. (A) Although interlocking protrusions (p) still retain their normal-appearing configurations in superficial fiber cells, spotty adherens junctions were not readily visible at the corners of all protrusions shown. Arrows show several possible degraded spotty adherens junctions at the bottom of protrusions. In contrast, in the slightly deeper disorganized regions, many protrusions underwent significant shape changes into round or oval shapes with increasing sizes (B). Some were seen separated from the intact cell membrane (cm) to become isolated membrane-bound globules (C). High magnification reveals that representative isolated globules (g) contain light electron-density protein content, and are enclosed by double layers of wavy cell membranes (arrow heads) (D–E). The double cell membranes sometime form the unique aquaporin-0 thin junctions (arrows), approximately 12–14 nm in thickness (inset in D). A possible degraded adherens junction (open arrow) may also be seen associated with the membranous globule. In addition, in the much deeper cortex, the second type of isolated membranous globules (g), characterized by the dark electron densities, is often distributed randomly in the disorganized fiber cell regions (F–H). The isolated dark-density globules are most likely due to more accessible penetrations of osmium tetroxide and uranyl acetate stain into their contents, suggesting that they belong to the more damaging mature isolated type. High magnification also confirms that the isolated dark-density globules are bounded by double layers of cell membranes (arrow heads) which sometime form the unique aquaporin-0 thin junctions (arrows). Scale bars: A, C and G = 500 nm; B and F= 1000 nm; D, E and H = 200 nm. Inset in C = 20 nm.

3.6. Disruption of N-cadherin-catenin complexes in ephrin-A5−/− lenses

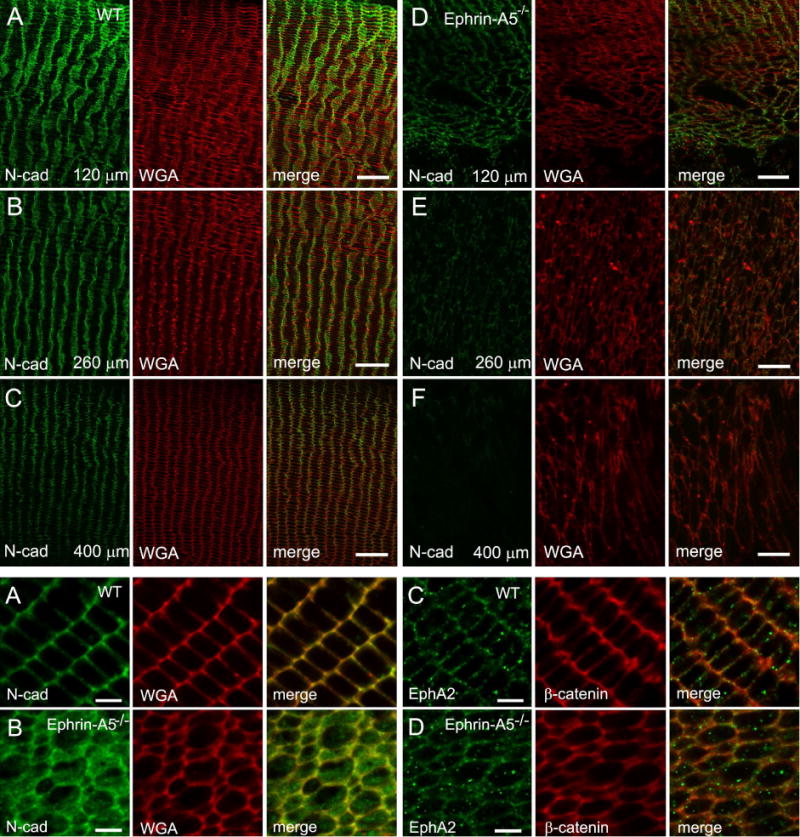

To further correlate the possible disruption of the adherens junctions in interlocking protrusions of ephrin-A5−/− lenses, we first compared the possible difference in immunoreactivity of N-cadherin between the same-age wild-type and ephrin-A5−/− lenses from the superficial cortex to deep cortex using systematic immunofluorescence labeling in frozen cross-sections. Figure 7 shows at the lower view that the N-cadherin immunoreactivity indeed underwent significant decrease from superficial cortex to deep cortex within approximately 400 μm deep from the lens surface as compared with the wild-type (A-F upper panel). At higher magnification, a significant increase in the labeling of N-cadherin immunoreactivity in the fiber cell cytoplasm was evidenced in the epherin-A5−/− lens, but not in the wild-type (Fig. 7A–B lower panel), suggesting that N-cadherin dislocation from the cytoplasmic membrane into the cell cytoplasm. Similarly, β-catenin, the junctional plaque protein, also exhibited dispersed labeling, in less degree, along the disorganized cell membranes as compared with that of the wild-type (Fig. 7C–D lower panel).

Fig. 7.

Immunofluorescence labeling for the N-cadherin and β-catenin in wild type and ephrin-A5−/− mouse lenses at 12 weeks or 3 weeks old. The upper panel (A–F) shows significant decrease of N-cadherin immunoreactivity in fiber cell membrane from the superficial cortex to deep cortex in the ephrin-A5−/− lenses as compared with the wild type at 12 weeks old. The consecutive images were taken at the low magnification from the superficial to deep cortical fibers of cross sections along the equatorial plane. The approximate bottom location of each image (i.e., 120 μm, 260 μm and 400 μm) is indicated. The lower panel reveals at the high magnification that N-cadherin underwent early dislocation from the cortical fiber cells in the ephrin-A5−/− lenses at 3 weeks old (A–B). While the labeling for the N-cadherin (A) antibody is distributed evenly along the cortical fiber cell membranes in wild-type lens, the N-cadherin immunoreactivity is markedly released into cytoplasm of cortical fiber cells in ephrin-A5−/− lenses (B). However, the β-catenin labeling displays similar but lesser alterations (C–D). In addition, the labeling for EphA2 receptor antibody shows no change in cortical fiber cell membranes in both wild-type (C) and ephrin-A5−/− lenses (D). WGA is used here as a cell membrane marker. Scale bars: 20 μm for upper panel (A–F) and 5 μm for lower panel (A–D).

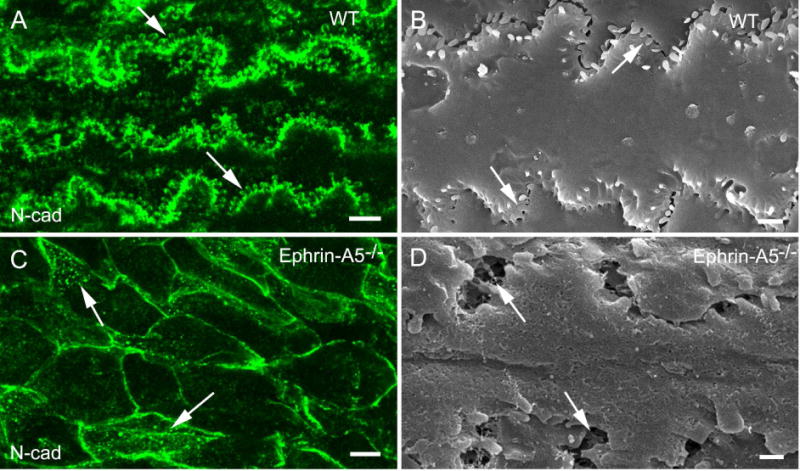

Furthermore, by using the whole-mount preparations, the specific association of N-cadherin labeling with the interlocking protrusions was clearly seen along the broad-side cortical fiber cells in wild-type lens (Fig. 8A–B). In contrast, the dotted N-cadherin labeling was scattered mostly in the cytoplasm of disorganized fiber cells in ephrin-A5−/− lenses (Fig. 8C–D), consistent with the dislocation of N-cadherin.

Fig. 8.

Immunofluorescence labeling on whole-mount samples for the N-cadherin in wild-type and ephrin-A5−/− mouse lenses at age 4 weeks. Whole-mount preparations of cortical fiber cells greatly facilitate visualization and labeling of interlocking protrusions. The labeling of the extracellular domains of N-cadherin antibody is clearly visualized along the protrusion membrane domains (arrows) in wild-type lens (A). This labeling pattern correlates well with the distribution of protrusions viewed on the SEM image (B). In contrast, the labeling of the extracellular domains of N-cadherin antibody is greatly defused into cytoplasm (arrows) of disorganized fiber cells in epherin-A5−/− mouse cataracts (C). SEM shows areas of enlarged extracellular spaces (arrows) in disorganized fiber cells of epherin-A5−/− lens (D). Scale bars: A and C = 5 μm; B and D = 1 μm.

Taken together, the above structural results suggested that the isolated membranous globules were likely originated from the intact interlocking protrusions based on their unique structural features as examined with SEM, thin-section TEM, freeze-fracture TEM and membrane cholesterol distribution. In addition, the immunofluorescence labeling data seem to further support the notion that the progressive, significant disruption of N-cadherin/adherens junctions, initiated from the younger outer cortical fibers, results in the late breakdown of the associated interlocking protrusions into isolate membranous globules in the older deep cortical and nuclear fibers in ephrin-A5−/− lenses.

4. Discussions

The mature lens consists of a single layer of lens epithelium in the frontal surface and the underlying highly elongated lens fiber cells. The proper packing of the lens fiber cells is crucial for lens clarity. It has been shown that there exist many interlocking protrusions between lens fiber cells that tightly fit the cells together like jigsaw puzzle pieces (Kuszak and Costello, 2004). These interlocking structures likely contribute to the stability of the lens while maintaining its transparency. Interruption of these interlocking protrusions has been shown to contribute to the development of cataracts, possibly due to light scattering properties of these disorganized membrane-bound globules. We have shown here that inactivation of the Eph family of tyrosine kinase receptor ligand, ephrin-A5, results in deficiencies in the interlocking protrusions between lens fiber cells (Figs. 6 and 8). The deep cortex and nucleus of the mutant lens often slips toward the posterior surface causing rupture of the posterior lens capsule, suggesting that the disruption of the interlocking protrusions also destabilizes lens fiber cell-cell interaction.

Ephrin-A5 has been shown to activate several Eph families of tyrosine kinase receptors including EphA2 (Pasquale, 1997; Zhou, 1998; Cooper et al., 2008; Himanen et al., 2010). Recent genetic analyses have shown that the 1p36 locus long known to be associated with human cataracts encodes mutated EPHA2 with mutations in the intracellular compartment of the receptor, specifically within the kinase and SAM domains, and different mutations appear to cause different cataract phenotypes (Jun et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Shentu et al., 2013). The EPHA2 mutations in the kinase domain, Arg721Gln (R721N), identified in Caucasian populations are associated with autosomal dominant cortical cataracts (Jun et al., 2009). Another kinase domain mutation, c.2353G > A, results in the change of alanine to threonine at codon 785 (A785T), and leads to the formation of recessive nuclear cataracts (Kaul et al., 2010). Similarly, mutations found in or near the SAM domain also cause various types of cataracts including nuclear (Dave et al., 2013), subscapular/cortical (Dave et al., 2013), and posterior polar (Shiels et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009) cataracts. However, all SAM domain mutations are dominant, suggesting that they interfere with the wild-type EPHA2 receptor functions in lens development and function (Dave et al., 2013; Park et al., 2013; Reis et al., 2014). Our recent studies show that several SAM domain mutations result in the formation of large protein aggregates which lead to a significant reduction of EPHA2 protein levels (Park et al., 2012). Thus, these mutant proteins may precipitate out and deplete wild type EPHA2 protein in the lens fiber cells, resulting in dominant deficiencies (Park et al., 2012). EPHA2 polymorphism has also been found to be associated with age-related cataracts (Jun et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2011; Sundaresan et al., 2012). In addition to the receptor EPHA2, a recent study also detected association of ephrin-A5 single nucleotide polymorphism with age-related cataracts (Lin et al., 2014). Thus, ephrin-A5/EPHA2 ligand-receptor interaction plays key roles in maintaining lens clarity and structural integrity. How the ligand-receptor interaction regulates lens structure and function is currently not clear. It has been shown that the R721N kinase domain missense mutation significantly alters EPHA2 signaling and cellular regulation, with significantly greater growth inhibition by ephrin-A1, suggesting a gain of function (Jun et al., 2009). In mouse lens, there is evidence that EphA2 is also required for proper equatorial epithelial cell migration and alignment (Shi et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2013). We do not think it is likely that the loss of ephrin-A5 activity directly results in nuclear fiber cell death, since the lens remains transparent for over 2 to 3 months. Also, fiber cell disorganization and N-cadherin dislocation have been observed from postnatal day 6, long before cataract development and any cell death occurs (Cooper et al., 2008). Thus, although we cannot exclude a role of ephori-A5 in lens fiber cell survival, their eventual death is more likely the results of fiber cell disorganization due to defective adherens junctions.

Our previous studies showed that loss of ephrin-A5 activity leads to the dislocation of N-cadherin from the lens fiber cell membrane (Cooper et al., 2008). Consistent with a function of ephrin-A5/EphA2 in regulating adherens junctions, we showed that EphA2 physically interact with β-catenin, and ephrin-A5 stimulation results in the increased interaction of N-cadherin with β-catenin (Cooper et al., 2008). These observations suggest a critical function of ephrin-A5/EphA2 in mediating lens cell-cell interaction by modulating adherens junctions. Our current ultrastructural and immunofluorescence analyses reveal abundant adherens junctions and N-cadherin protein localization on the interlocking membrane protrusions of the lens fiber cells (Figs. 5 and 8). We speculate that adherens junction complexes help stabilize the interlocking membrane protrusions between neighboring lens fiber cells and thus generating tightly packed lens. Disruption of ephrin-A5 function leads to the destabilization of these interlocking protrusions and weakened cell-cell interaction, generating irregular and abnormally arranged membrane globules, leading to cataracts and lens rupture (Figs. 6 and 9). Our observations are also consistent with studies by Shi et al. (Shi et al., 2012) showing that loss of EphA2 function also leads to abnormal lens fiber cell membrane protrusions. A number of early studies have also demonstrated that globules of various sizes formed by different causes are responsible for producing light scatter and lens opacities in human and animal lenses (Creighton et al., 1978; Mousa et al., 1979; Harding et al., 1982; Lo, 1989; Bhatnagar et al., 1995).

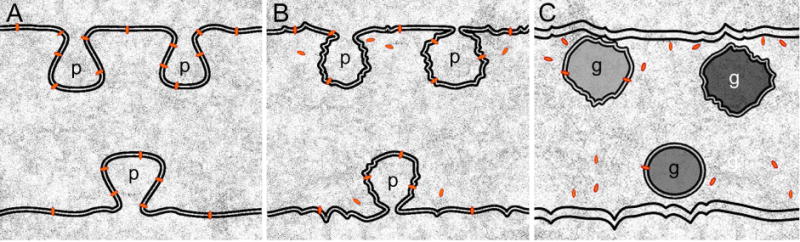

Fig. 9.

A model of dissociation of the interlocking protrusions between lens fiber cells in the absence of ephrin-A5 function. A relatively normal configuration of elongated protrusions is regularly present between transparent superficial cortical fiber cells in ephrin-A5−/− lenses (A). The N-cadherin proteins (red bullets), and their associated adherens junctions, are richly associated with the protrusions. In the deeper cortical and nuclear regions, interlocking protrusions progressively undergo shape changes and dissociations from the cell membranes to form isolated membranous globules due to breakdown of N-cadherin-catenin complexes and associated adherens junctions in ephrin-A5−/− lenses (B–C). An accumulation of abundant isolated large globules at different maturation stages in the cells can cause light scatter and opacification in the deeper cortex and nucleus in ephrin-A5−/− lenses.

Since EPHA2 mutations cause cataracts in humans, it is likely that the receptor mutations also result in deficiencies in the interlocking protrusions between lens fiber cells, although this is yet to be demonstrated. In addition, more research is needed to discern whether it is the loss of adherens junctions or there are additional cell-cell interaction defects that are responsible for the cellular and lens defects.

Highlights.

Disruption of interlocking protrusions produces abundant globules in ephrin-A5−/− lens.

Numerous large globules are the source of light scatter and lens opacity.

N-cadherin and adherens junctions are highly enriched in protrusions in normal lens.

Breakdown of N-cadherin and junctions contributes to lens opacity in ephrin-A5−/− lens.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pat Abramson for graphic support and Lawrence Brako for technical assistance. This study was supported by NEI/NIH grants EY05314 to W.K.L., EY019012 to R.Z., and Grant RR03034 from the Research Centers in Minority Institutions, National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health to Morehouse School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atreya PL, Barnes J, Katar M, Alcala J, Maisel H. N-cadherin of the human lens. Curr Eye Res. 1989;8:947–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi M, Katar M, Lewis J, Maisel H. Associated proteins of lens adherens junction. J Cell Biochem. 2002;86:700–703. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar A, Ansari NH, Wang L, Khanna P, Wang C, Srivastava SK. Calcium-mediated disintegrative globulization of isolated ocular lens fibers mimics cataractogenesis. Exp Eye Res. 1995;61:303–310. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Brako L, Gu S, Jiang JX, Lo WK. Regional changes of AQP0-dependent square array junction and gap junction associated with cortical cataract formation in the Emory mutant mouse. Exp Eye Res. 2014a;127:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Brako L, Lo WK. Massive formation of square array junctions dramatically alters cell shape but does not cause lens opacity in the cav1-KO mice. Exp Eye Res. 2014b;125:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Jiang JX, Lo WK. Gap junction remodeling associated with cholesterol redistribution during fiber cell maturation in the adult chicken lens. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1492–1508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Lee JE, Brako L, Jiang JX, Lo WK. Gap junctions are selectively associated with interlocking ball-and-sockets but not protrusions in the lens. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2328–2341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Ansari MM, Cooper JA, Gong X. EphA2 and Src regulate equatorial cell morphogenesis during lens development. Development. 2013;140:4237–4245. doi: 10.1242/dev.100727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AI. The electron microscopy of the normal human lens. Invest Ophthalmol. 1965;4:433–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA, Son AI, Komlos D, Sun Y, Kleiman NJ, Zhou R. Loss of ephrin-A5 function disrupts lens fiber cell packing and leads to cataract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16620–16625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808987105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello MJ, McIntosh TJ, Robertson JD. Membrane specializations in mammalian lens fiber cells: distribution of square arrays. Curr Eye Res. 1985;4:1183–1201. doi: 10.3109/02713688509003364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton MO, Trevithick JR, Mousa GY, Percy DH, McKinna AJ, Dyson C, Maisel H, Bradley R. Globular bodies: a primary cause of the opacity in senile and diabetic posterior cortical subcapsular cataracts? Can J Ophthalmol. 1978;13:166–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave A, Laurie K, Staffieri SE, Taranath D, Mackey DA, Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Craig JE, Burdon KP, Sharma S. Mutations in the EPHA2 gene are a major contributor to inherited cataracts in South-Eastern Australia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DH, Crock GW. Interlocking patterns on primate lens fibers. Invest Ophthalmol. 1972;11:809–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B, Volk T, Volberg T, Bendori R. Molecular interactions in adherens-type contacts. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1987;8:251–272. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1987.supplement_8.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CV, Chylack LT, Jr, Susan SR, Lo WK, Bobrowski WF. Elemental and ultrastructural analysis of specific human lens opacities. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1982;23:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himanen JP, Yermekbayeva L, Janes PW, Walker JR, Xu K, Atapattu L, Rajashankar KR, Mensinga A, Lackmann M, Nikolov DB, Dhe-Paganon S. Architecture of Eph receptor clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10860–10865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004148107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun G, Guo H, Klein BE, Klein R, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Miao H, Lee KE, Joshi T, Buck M, Chugha P, Bardenstein D, Klein AP, Bailey-Wilson JE, Gong X, Spector TD, Andrew T, Hammond CJ, Elston RC, Iyengar SK, Wang B. EPHA2 is associated with age-related cortical cataract in mice and humans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul H, Riazuddin SA, Shahid M, Kousar S, Butt NH, Zafar AU, Khan SN, Husnain T, Akram J, Hejtmancik JF, Riazuddin S. Autosomal recessive congenital cataract linked to EPHA2 in a consanguineous Pakistani family. Mol Vis. 2010;16:511–517. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistler J, Gilbert K, Brooks HV, Jolly RD, Hopcroft DH, Bullivant S. Membrane interlocking domains in the lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:1527–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuck JF, Kuwabara T, Kuck KD. The Emory mouse cataract: an animal model for human senile cataract. Curr Eye Res. 1981;1:643–649. doi: 10.3109/02713688109001868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuszak J, Alcala J, Maisel H. The surface morphology of embryonic and adult chick lens-fiber cells. Am J Anat. 1980;159:395–410. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001590406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara T. The maturation of the lens cell: a morphologic study. Exp Eye Res. 1975;20:427–443. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(75)90085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Zhou N, Zhang N, Qi Y. Mutational screening of EFNA5 in Chinese age-related cataract patients. Ophthalmic Res. 2014;52:124–129. doi: 10.1159/000363139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WK. Adherens junctions in the ocular lens of various species: ultrastructural analysis with an improved fixation. Cell Tissue Res. 1988;254:31–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00220014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WK. Visualization of crystallin droplets associated with cold cataract formation in young intact rat lens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:9926–9930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WK, Biswas SK, Brako L, Shiels A, Gu S, Jiang JX. Aquaporin-0 targets interlocking domains to control the integrity and transparency of the eye lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:1202–1212. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WK, Harding CV. Square arrays and their role in ridge formation in human lens fibers. J Ultrastruct Res. 1984;86:228–245. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(84)90103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WK, Reese TS. Multiple structural types of gap junctions in mouse lens. J Cell Sci. 1993;106(Pt 1):227–235. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WK, Shaw AP, Paulsen DF, Mills A. Spatiotemporal distribution of zonulae adherens and associated actin bundles in both epithelium and fiber cells during chicken lens development. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:45–55. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel H, Atreya P. N-cadherin detected in the membrane fraction of lens fiber cells. Experientia. 1990;46:222–223. doi: 10.1007/BF02027322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa GY, Creighton MO, Trevithick JR. Eye lens opacity in cortical cataracts associated with actin-related globular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 1979;29:379–391. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(79)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JE, Son AI, Hua R, Wang L, Zhang X, Zhou R. Human cataract mutations in EPHA2 SAM domain alter receptor stability and function. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JE, Son AI, Zhou R. Roles of EphA2 in Development and Disease. Genes (Basel) 2013;4:334–357. doi: 10.3390/genes4030334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. The Eph family of receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:608–615. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis LM, Tyler RC, Semina EV. Identification of a novel C-terminal extension mutation in EPHA2 in a family affected with congenital cataract. Mol Vis. 2014;20:836–842. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shentu XC, Zhao SJ, Zhang L, Miao Q. A novel p.R890C mutation in EPHA2 gene associated with progressive childhood posterior cataract in a Chinese family. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6:34–38. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.01.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, De Maria A, Bennett T, Shiels A, Bassnett S. A role for epha2 in cell migration and refractive organization of the ocular lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:551–559. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels A, Bennett TM, Knopf HL, Maraini G, Li A, Jiao X, Hejtmancik JF. The EPHA2 gene is associated with cataracts linked to chromosome 1p. Mol Vis. 2008;14:2042–2055. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son AI, Cooper MA, Sheleg M, Sun Y, Kleiman NJ, Zhou R. Further analysis of the lens of ephrin-A5−/− mice: development of postnatal defects. Mol Vis. 2013;19:254–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son AI, Park JE, Zhou R. The role of Eph receptors in lens function and disease. Sci China Life Sci. 2012;55:434–443. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub BK, Boda J, Kuhn C, Schnoelzer M, Korf U, Kempf T, Spring H, Hatzfeld M, Franke WW. A novel cell-cell junction system: the cortex adhaerens mosaic of lens fiber cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4985–4995. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan P, Ravindran RD, Vashist P, Shanker A, Nitsch D, Talwar B, Maraini G, Camparini M, Nonyane BA, Smeeth L, Chakravarthy U, Hejtmancik JF, Fletcher AE. EPHA2 polymorphisms and age-related cataract in India. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W, Hou S, Jiang Z, Hu Z, Yang P, Ye J. Association of EPHA2 polymorphisms and age-related cortical cataract in a Han Chinese population. Mol Vis. 2011;17:1553–1558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk T, Geiger B. A-CAM: a 135-kD receptor of intercellular adherens junctions. I Immunoelectron microscopic localization and biochemical studies. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1441–1450. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willekens B, Vrensen G. The three-dimensional organization of lens fibers in the rhesus monkey. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1982;219:112–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02152295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampighi GA, Hall JE, Ehring GR, Simon SA. The structural organization and protein composition of lens fiber junctions. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2255–2275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Hua R, Xiao W, Burdon KP, Bhattacharya SS, Craig JE, Shang D, Zhao X, Mackey DA, Moore AT, Luo Y, Zhang J, Zhang X. Mutations of the EPHA2 receptor tyrosine kinase gene cause autosomal dominant congenital cataract. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E603–E611. doi: 10.1002/humu.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou CJ, Lo WK. Association of clathrin, AP-2 adaptor and actin cytoskeleton with developing interlocking membrane domains of lens fibre cells. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:423–432. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R. The Eph family receptors and ligands. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:151–181. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]