Abstract

Background and Purpose

Inhibition of diacylglycerol lipase (DGL)β prevents LPS‐induced pro‐inflammatory responses in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Thus, the present study tested whether DGLβ inhibition reverses allodynic responses of mice in the LPS model of inflammatory pain, as well as in neuropathic pain models.

Experimental Approach

Initial experiments examined the cellular expression of DGLβ and inflammatory mediators within the LPS‐injected paw pad. DAGL‐β (−/−) mice or wild‐type mice treated with the DGLβ inhibitor KT109 were assessed in the LPS model of inflammatory pain. Additional studies examined the locus of action for KT109‐induced antinociception, its efficacy in chronic constrictive injury (CCI) of sciatic nerve and chemotherapy‐induced neuropathic pain (CINP) models.

Key Results

Intraplantar LPS evoked mechanical allodynia that was associated with increased expression of DGLβ, which was co‐localized with increased TNF‐α and prostaglandins in paws. DAGL‐β (−/−) mice or KT109‐treated wild‐type mice displayed reductions in LPS‐induced allodynia. Repeated KT109 administration prevented the expression of LPS‐induced allodynia, without evidence of tolerance. Intraplantar injection of KT109 into the LPS‐treated paw, but not the contralateral paw, reversed the allodynic responses. However, i.c.v. or i.t. administration of KT109 did not alter LPS‐induced allodynia. Finally, KT109 also reversed allodynia in the CCI and CINP models and lacked discernible side effects (e.g. gross motor deficits, anxiogenic behaviour or gastric ulcers).

Conclusions and Implications

These findings suggest that local inhibition of DGLβ at the site of inflammation represents a novel avenue to treat pathological pain, with no apparent untoward side effects.

Abbreviations

- 2‐AG

2‐arachidonoylglycerol

- ABHD6

α β hydrolase domain‐containing protein 6

- CCI

chronic constriction injury

- CINP

chemotherapy‐induced peripheral neuropathy

- DGL, (also known as DAGL)

diacylglycerol lipase

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- MGL

monoacylglycerol lipase

- THC

Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| GPCRs a | Enzymes b |

| CB1 receptor | DGLα |

| CB2 receptor | DGLβ |

| MGL |

| LIGANDS | |

|---|---|

| 2‐AG | Paclitaxel |

| Arachidonic acid | PGE2 |

| Diclofenac | TNF‐α |

| LPS |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (a,bAlexander et al., 2015a, 2015b).

Introduction

Diacylglycerol lipase (DGL) α and β (Bisogno et al., 2003; Gao et al., 2010; Tanimura et al., 2010) play important roles in transforming diacylglycerols into 2‐arachidonoylglyercol (2‐AG), the most prevalent endocannabinoid expressed in the brain (Mechoulam et al., 1995; Sugiura et al., 1995). This endocannabinoid participates in proper neuronal function (Goncalves et al., 2008; Tanimura et al., 2010) and mediates neuronal axonal growth (Williams et al., 2003), skeletal muscle differentiation (Iannotti et al., 2014) and retrograde suppression of synaptic transmission (Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001; Ohno‐Shosaku et al., 2001; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001; Pan et al., 2009). These enzymes are differentially expressed on cells in the nervous system and peripheral tissue (Hsu et al., 2012). Specifically, DGLα is more highly expressed than DGLβ throughout the CNS (e.g. hippocampus, frontal cortex, amygdala, cerebellum and spinal cord). DGLα is expressed on postsynaptic neurons within various brain regions (Katona et al., 2006; Yoshida et al., 2006; Lafourcade et al., 2007; Uchigashima et al., 2007) and is particularly abundant in the vicinity of dendritic spines. Although the relative expression of DGLβ throughout the brain is generally sparse, it is highly expressed on microglia and, in the periphery, is most highly expressed on peritoneal macrophages (Hsu et al., 2012). This distribution pattern is consistent with the idea that DGLβ contributes to inflammatory responses (Hsu et al., 2012).

Genetic deletion of DGLα results in marked decreases in 2‐AG and arachidonic acid in brain (Gao et al., 2010; Tanimura et al., 2010; Shonesy et al., 2014) and spinal cord (Gao et al., 2010). Whereas Gao et al. (2010) also reported that DAGL‐β (−/−) mice express reduced levels of 2‐AG in whole brain albeit not to the same magnitude of DAGL‐α deletion, Hsu et al. (2012) found that DAGL‐β (−/−) or wild‐type mice treated with selective DGLβ inhibitors express wild‐type levels of 2‐AG in the brain. However, DGLβ inhibitors lead to decreased levels of 2‐AG in LPS‐treated peritoneal macrophage cell cultures from C57Bl/6 mice (Hsu et al., 2012).

Not surprisingly, these two enzymes play markedly distinct roles in various physiological functions. Most notably, DAGL‐α (−/−) mice display impaired retrograde suppression of synaptic transmission in the prefrontal cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus and striatum (Gao et al., 2010; Tanimura et al., 2010; Yoshino et al., 2011). In contrast, these endocannabinoid‐mediated forms of retrograde synaptic suppression are spared in DAGL‐β (−/−) mice (Gao et al., 2010). Moreover, adult neurogenesis is compromised in both the hippocampus and subventricular zone in DAGL‐α (−/−) mice, but DAGL‐β (−/−) mice display a phenotypic reduction of neurogenesis in hippocampus, only. In contrast, DGLβ appears to play a role in inflammatory responses. The selective DGLβ inhibitors, KT109, KT172 or DAGL‐β deletion, protected mouse peritoneal macrophages from LPS‐induced production of prostaglandins (e.g. PGE2 and PGD2) and pro‐inflammatory cytokines (eg TNF‐α and IL‐1β; Hsu et al., 2012). These marked anti‐inflammatory actions suggest that DGLβ inhibition represents a novel strategy for reducing pathological pain.

The primary objective of the present study was to test whether DGLβ inhibition reduces nociceptive behaviour in the mouse LPS model of inflammatory pain. In initial experiments, we used immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy to examine the impact of an intraplantar injection of LPS on DGLβ protein expression, as well as its co‐localization with pro‐inflammatory markers and immune cells. Complementary pharmacological and genetic approaches were used to investigate whether blockade of DGLβ reduces LPS‐induced mechanical allodynia. Because the DGLβ inhibitor KT109 also inhibits the serine hydrolase α β hydrolase domain‐containing protein 6 (ABHD6) (Hsu et al., 2012), an enzyme known to hydrolyze 2‐AG (Blankman et al., 2007; Marrs et al., 2010) and is expressed on postsynaptic neurons, we employed the selective ABHD6 inhibitor KT195, which lacks DGLβ activity (Hsu et al., 2012), as a control. Another objective of this work was to elucidate the locus of action for the antinociceptive effects of KT109. Accordingly, we administered KT109 directly into the LPS‐treated paw to assess whether it produced its antinociceptive effects locally. Additionally, we examined whether central administration of KT109 reduces LPS‐induced nociceptive behaviour by injecting it either i.c.v. or i.t. In addition to testing KT109 in the LPS model of inflammatory pain, we examined its antinociceptive effects in the chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve model of neuropathic pain and the paclitaxel model of chemotherapy‐induced neuropathic pain (CINP). Finally, we tested for possible side effects of KT109, such as gastric ulcerogenic effects, as well as alterations in anxiogenic behaviour (light/dark box assay (Holmes, 2001)), locomotor behaviour, body temperature and acute thermal antinociceptive responses (Little et al., 1988).

Methods

Animals

Adult male C57BL/6J mice (23–40 g, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) served as subjects in these experiments. DAGL‐β knockout (−/−) mice were generated in the Cravatt laboratory on a mixed C57BL/6 and 129/SvEv background, as previously described (Hsu et al., 2012), and transferred to Virginia Commonwealth University. Transgenic mice lacking functional cannabinoid CB1 receptors (CB1) or cannabinoid CB2 receptors (CB2) were bred at Virginia Commonwealth University. Mice lacking either CB1 (gifted originally from the Zimmer laboratory) or CB2 (from Jackson Laboratories) receptors were backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background for more than 15 or 8 generations respectively. A total of 24 CB1 (−/−) mice, 24 CB2 (−/−) mice and 93 DAGL‐β (−/−) mice were used in these studies. Mice were housed four per cage in a temperature (20–22°C), humidity (55 ± 10%) and light‐controlled (12 h light/dark; lights on at 0600) AAALAC‐approved facility, with standard rodent chow and water available ad libitum.

All tests were conducted during the light phase. Mice weighed between 23 and 40 g. The sample sizes selected for each treatment group in each experiment were based on previous studies from our laboratory.

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Virginia Commonwealth University or West Virginia University and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011). After testing was completed, all mice were humanely killed via CO2 asphyxia, followed by rapid cervical dislocation. Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath & Lilley, 2015).

Acute i.t injection used in locus of action‐related experiments

Acute i.t. injections were performed as previously described (Wilkerson et al., 2012a, 2012b) but modified for mice. In brief, a 27‐gauge needle with the plastic hub removed was inserted at the end of the i.t. catheter, allowing for direct injection. Mice were anaesthetized via isofurane and shaved from the base of the tail to mid back. The lumbosacral enlargement was identified, and a 27‐gauge needle was inserted. Subjects received an injection containing 5 μL of drug or vehicle, which was gently infused at the level of lumbosacral enlargement (around L4–L5). Light tail twitching was typically observed, indicating successful i.t. placement. Drug or vehicle was injected over a 5 s interval. Drug treatment was randomly assigned to animals. Upon completion of injection, the 27‐gauge needle, with the i.t. catheter attached, was removed. A 100% motor recovery rate was observed from this injection procedure.

Acute i.c.v. injection used in locus of action‐related experiments

In order to test whether KT109 produced its antinociceptive effects through a supraspinal site of action, drugs were administered via acute i.c.v. injection. Mice were anaesthetized via isofurane on the evening prior to testing, and a scalp incision was made to expose the bregma. Unilateral injection sites were prepared using a 26‐gauge needle with a sleeve of polyurethane tubing to control the depth of the needle at a site −0.6 mm rostral and 1.2 mm lateral to the bregma at a depth of 2 mm. Animals had fully recovered within 10 min after anaesthesia was discontinued, and were monitored for 2 h post surgery for signs of distress and discomfort. Mice were again monitored the next morning, prior to the injection of drug, to ensure minimal discomfort, overall health and lack of infection around the injection site. Drugs were administered using a 26‐gauge needle on the morning of testing. The needle was held in place for 20 s to ensure drug delivery.

Experimental procedures

Immunohistochemical procedures from LPS‐treated mice

Mice were overdosed with vaporized isofurane, then perfused transcardially with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Whole feet with intact paw pads were removed and underwent overnight fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. All specimens were subjected to EDTA (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)‐induced decalcification for 20 days, and paw sections were subsequently paraffin processed, embedded, sliced and mounted on slides, as previously described (Wilkerson et al., 2012a, 2012b). Paws were sliced in a manner to ensure that only paw pads were examined.

Slides were prepared for immunohistochemistry as previously described (Wilkerson et al., 2012a, 2012b). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti‐DAGL‐β (ab103100, 1:600; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit anti‐TNF‐α (ab34674, 1:100; Abcam) (Folgosa et al., 2013; Kisiswa et al., 2013) rabbit anti‐PGE2 (ab2318, 1:250; Abcam) (George Paul et al., 2010; Ghosh et al., 2013a), rat anti‐CD68 (ab53444, 1:100; Abcam) (Wu et al., 2008) and rat anti‐CD4 (NB110‐97869, 1:200; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) (Thomas et al., 2015). Briefly, slides were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, in a humidity chamber, and with a fluorophore‐conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h the following day. For DGLβ, TNF‐α and PGE2, slides were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 h and then treated with Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) and stained using TSA Plus Fluorescein System (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA, USA) to allow for signal amplification and the ability to use a second primary antibody from the same host species. Slides were coverslipped with Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). After the first antibody staining procedure, the slides went through subsequent staining procedures, which took place over multiple days to account for the times needed for individual antibody incubation and staining.

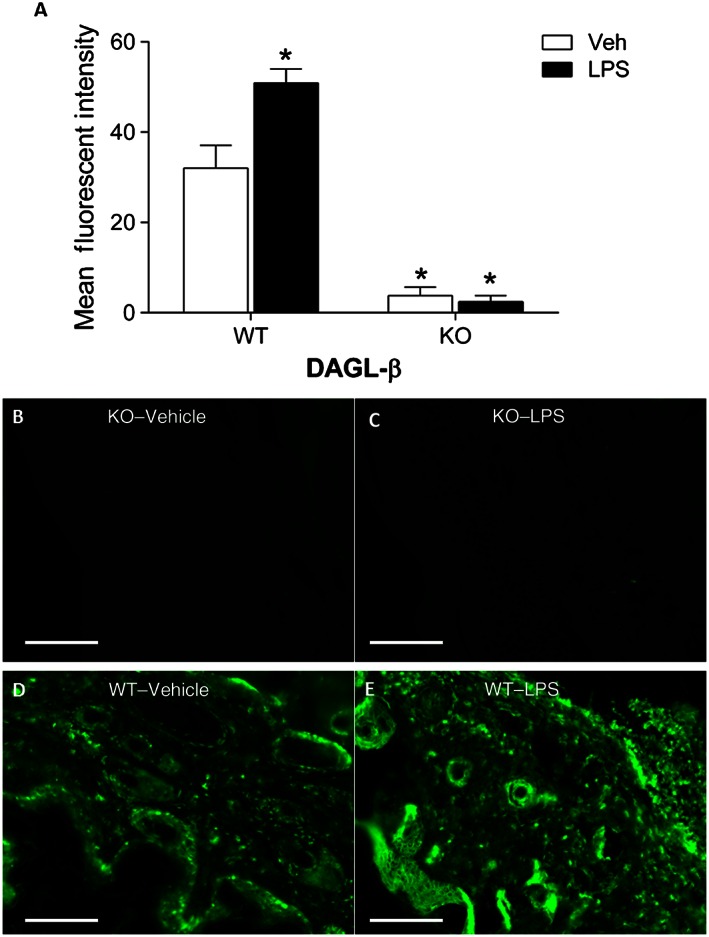

As a control for nonselective DGLβ staining characterization with the commercially available antibody, paw pads from DAGL‐β (−/−) and (+/+) mice were stained using the above procedures (Figure 1) and imaged on a Zeiss AxioImager Z2 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, AG, Germany). Tissue was analysed as describe below with image j, with DAGL‐β (−/−) tissue serving as the control tissue. Notably, DAGL‐β (−/−) tissue with the DAGL‐β antibody showed negligible staining compared to DAGL‐β (−/−) tissue without antibody.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of DGLβ in DAGL‐β (−/−) (KO) and (+/+) (WT) paw pads treated with LPS or vehicle. (A) DGLβ immunoreactivity was absent in DAGL‐β (−/−) paw pads but is increased in DAGL‐β (+/+) paw pads treated with LPS compared with vehicle‐injected paws. (B–E) Representative images of DGLβ staining (green). *P < 0.05 versus WT – vehicle. Scale bars are equal to 50 μm, n = 4 mice per group.

image j software analysis

Fluorescent images for standard fluorescence analysis were obtained in the same manner as detailed above and analysed as previously described (Wilkerson et al., 2012b). Briefly, images were taken on a Zeiss AxioImager Z2 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, AG), and only images containing paw pad, rather than muscle or other tissues, were utilized (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Images were then converted to grey scale and analysed using image j software available for free download at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/. Briefly, a total of four tissue sections from a single animal were averaged to obtain an individual animal's overall fluorescent intensity, with three animals in each experimental treatment group, to generate an average for that experimental condition. Likewise, background values were generated from control tissues incubated with PBS and the given secondary antibody and averaged together. The average background was then subtracted from the average of each experimental treatment group.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy at 63× magnification was performed on a Zeiss AxioObserver inverted LSM710 META confocal microscope utilizing zen 2012 software (Carl Zeiss, AG). Final images were generated from collapsed z‐stacks comprising 17 images taken 0.47 μm apart on the z‐axis.

LPS inflammatory pain model

Mice were given an injection of 2.5 μg LPS from Escherichia coli (026:B6, Sigma), in 20 μL of physiological sterile saline (Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) into the plantar surface of the right hind paw. As previously reported, this is the minimally effective dose of LPS that elicits mechanical allodynia but producing measurable increases in paw thickness (Booker et al., 2012). Mice were returned to their home cages after LPS injection for 22 h before all experiments were commenced, except time course studies in which allodynia was assessed at 0.67, 1, 3, 5, 8 and 24 h.

To determine whether repeated administration of KT109 would prevent LPS‐induced allodynia, mice were given i.p. injections of vehicle or KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) once a day for 5 days. On day 5, each mouse received its appropriate i.p. injection of vehicle or KT109, and 2 h later, all mice were given an intraplantar injection of LPS. On day 6 (22 h after LPS administration), each mouse received its final i.p. injection. The vehicle‐treated mice were divided into two groups. The first group received another injection of vehicle (vehicle control group), and the second group was given 40 mg·kg−1 KT109 (acute KT109 group). The mice that had been given repeated injections of drug received their final injection of KT109 (repeated KT109 group). All mice were tested for mechanical allodynia 2 h after the final i.p. injection.

CCI neuropathic pain model

Following baseline behavioural assessment for von Frey thresholds and hotplate responses, the surgical procedure for chronic constriction of the sciatic nerve was conducted as previously described (Bennett and Xie, 1988; Wilkerson et al., 2012a, 2012b) but modified for mice as previously described (Ignatowska‐Jankowska et al., 2015). Mice were anaesthetized using isoflurane (induction 5% volume followed by 2.0% in oxygen). The mid‐to‐low back region and the dorsal left thigh were shaved and cleaned with 75% ethanol. Using aseptic procedures, the sciatic nerve was carefully isolated and loosely ligated using three segments of 5–0 chromic gut sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA). Sham surgery was identical to CCI surgery but without the loose nerve ligation. The overlying muscle was sutured closed with (1) 4–0 sterile silk suture (Ethicon), and animals recovered from anaesthesia within approximately 5 min. Animal placement into either CCI or sham surgical groups was randomly assigned. The order of drug administration was randomized, and a minimum 72 h washout period was imposed between each test day.

Paclitaxel model of chemotherapy‐induced neuropathic pain

Following baseline behavioural assessment for von Frey thresholds, mice were given an i.p. injection of paclitaxel (8 mg·kg−1) or vehicle, consisting of physiological sterile saline (Hospira Inc.) every other day for a total of four injections. This protocol has been well characterized to produce bilateral allodynia (Smith et al., 2004). Mice were assessed for mechanical allodynia after finishing all four injections. A within subject design was used for drug administration, with treatments for each mouse being 1.6, 5 and 40 mg·kg−1 KT109, and 1:1:18 vehicle, as described above. The order of drug administration was randomized, and a minimum 72 h washout period was imposed between each test day.

Behavioural assessment of nociception

Baseline responses to light mechanical touch were assessed using the von Frey test following habituation to the testing environment, as described elsewhere (Murphy et al., 1999). In brief, mice were placed atop a wire mesh screen, with spaces 0.5 mm apart, and habituated for approximately 30 min·day−1 for 4 days. Mice were unrestrained and were singly placed under an inverted wire mesh basket to allow for unrestricted air flow. The von Frey test utilizes a series of calibrated monofilaments, (2.83–4.31 log stimulus intensity; North Coast Medical, Morgan Hills, CA, USA) applied randomly to the left and right plantar surfaces of the hind paw for 3 s. Lifting, licking or shaking the paw was considered a response. After completion of allodynia testing for CCI experiments, thermal hyperalgesia testing was performed in the hot plate test, as previously described (Ignatowska‐Jankowska et al., 2015). Mice were placed on a heated (52°C) enclosed Hot Plate Analgesia Meter (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA), and latency to jump or lick/shake the back paws was determined. A 30 s cut‐off time was utilized to avoid potential tissue damage. For all behavioural testing, threshold assessment was performed in a blinded fashion.

Gastric inflammatory lesion model

Gastric hemorrhages were induced and quantified as described previously (Liu et al., 1998; Kinsey et al., 2011a, 2011b). Mice were weighed and then placed on a wire mesh barrier (Thoren Caging Systems, Inc., Hazleton, PN, USA), and food deprived with free access to water. After 24 h, mice were administered KT109 (40 mg·kg−1, i.p.), vehicle or the nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug, diclofenac sodium (100 mg·kg−1, i.p.), which served as a positive control (Kinsey et al., 2011a, 2011b), and were returned to the home cage for 6 h. Mice were then killed via CO2 asphyxiation followed by rapid cervical dislocation, and stomachs were harvested, cut along the greater curvature, rinsed with distilled water and placed on a lighted tracing table (Artograph light pad 1920) and photographed (Canon T3 Rebel digital camera with a 10x lens). Image files were renamed, and an experimenter blinded to treatment conditions quantified the gastric haemorrhages, relative to a reference in each photo, using adobe photoshop (version CS5; Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA), as described previously (Nomura et al., 2011; Kinsey et al., 2013).

Tetrad assay

Mice (counterbalanced Latin square within subject design) were housed individually overnight. The behavioural testing was conducted in the following order: bar test (catalepsy), tail withdrawal test, rectal temperature and locomotor activity. Testing was performed according to previously described procedures (Long et al., 2009; Schlosburg et al., 2010). Catalepsy was assessed on a bar 0.7 cm in diameter placed 4.5 cm above the ground. The mouse was placed with its front paws on the bar and a timer (Timer #1) was started. A second timer (Timer #2) was turned on only when the mouse was immobile on the bar, with the exception of respiratory movements. If the mouse moved off the bar, it was placed back in the original position. The assay was stopped when either Timer #1 reached 60 s or after the fourth time the mouse moved off the bar, and the cataleptic time was scored as the amount of time on Timer #2. Nociception was then assessed in the tail immersion assay. The mouse was placed head first into a small bag fabricated from absorbent under pads (VWR Scientific Products, Radnor, PA, USA; 4 cm diameter, 11 cm length) with the tail out of the bag. Each mouse was handheld, and 1 cm of the tail was submerged into a 52°C water bath. The latency for the mouse to withdraw its tail within a 10 s cut‐off time was scored. Rectal temperature was assessed by inserting a thermocouple probe 2 cm into the rectum, and temperature was determined by a thermometer (BAT‐10 Multipurpose Thermometer; Physitemp Instruments Inc., Clifton, NJ, USA). Locomotor activity was assessed 120 min after treatment, for a 60 min period in a Plexiglas cage (42.7 × 21.0 × 20.4 cm) and any‐maze (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA) software was used to determine the percentage of time spent immobile, mean speed and distance travelled.

Light/dark box test

The light/dark box consisted of a small (36 × 10 × 34 cm) enclosed dark box with a passage way (6 × 6 cm) leading to a larger (36 × 21 × 34 cm) light box. Prior to testing, mice were acclimatized in the testing room for 1 h. As described previously (Hait et al., 2014), mice were placed in the light side of the box and allowed to explore the apparatus for 5 min. Time spent, total entries and distance travelled in the light and dark sides during the 5 min test were captured with a video monitoring system and measured by any‐maze software (Stoelting).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Student's t‐test or one‐way or two‐way ANOVA. Tukey's test was used for post hoc analysis following a significant one‐way ANOVA. Multiple comparisons following two‐way ANOVA were conducted with Bonferroni post hoc comparison. A P‐value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The computer programme graphpad prism version 4.03 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used in all statistical analyses. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015).

Drugs

The DGLβ inhibitor KT109 (4‐([1,1′‐biphenyl]‐4‐yl)‐1H‐1,2,3‐triazol‐1‐yl)(2‐benzylpiperidin‐1‐yl)methanone3‐1 (Hsu et al., 2012) and the structurally related ABHD6 selective inhibitor KT195 (Hsu et al., 2012) were synthesized by the Cravatt laboratory. Diclofenac sodium and paclitaxel were obtained commercially (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, and Tocris, Minneapolis, MN, USA, respectively). Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Bethesda, MD, USA). All drugs were dissolved in a vehicle solution consisting of a mixture of ethanol, alkamuls‐620 (Sanofi‐Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) and saline (0.9% NaCl) in a 1:1:18 ratio. All drugs were administered in a volume of 10 μL·g−1 body mass. Each drug was given via the i.p. route of administration, with the exception of the locus of action studies, in which drugs were given via an intraplantar injection into a hindpaw (i.paw), i.t. or introcerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection. For i.paw experiments, all drugs were administered in 20 μL, and for both i.t. and i.c.v. experiments, drugs were administered in 5 μL. The i.p. doses of KT109 selected were based on results reported by Hsu et al. (2012) indicating that acute administration of 20 mg·kg−1 of KT109 produces inhibition of DGLβ, as well as decreases in arachidonic acid in macrophages collected from mice treated with LPS. The dose range of intraplantar KT109 selected for study and injection volume were based, in part, on a previous study that examined intraplantar injection of an endocannabinoid catabolic enzyme inhibitor (Booker et al., 2012), as well as included an element of being empirically derived. Given that an intraplantar injection of 12 μg KT109 into the LPS‐treated paw, but not the contralateral paw, reversed the allodynia, this dose was further used in i.t. and i.c.v. studies.

Results

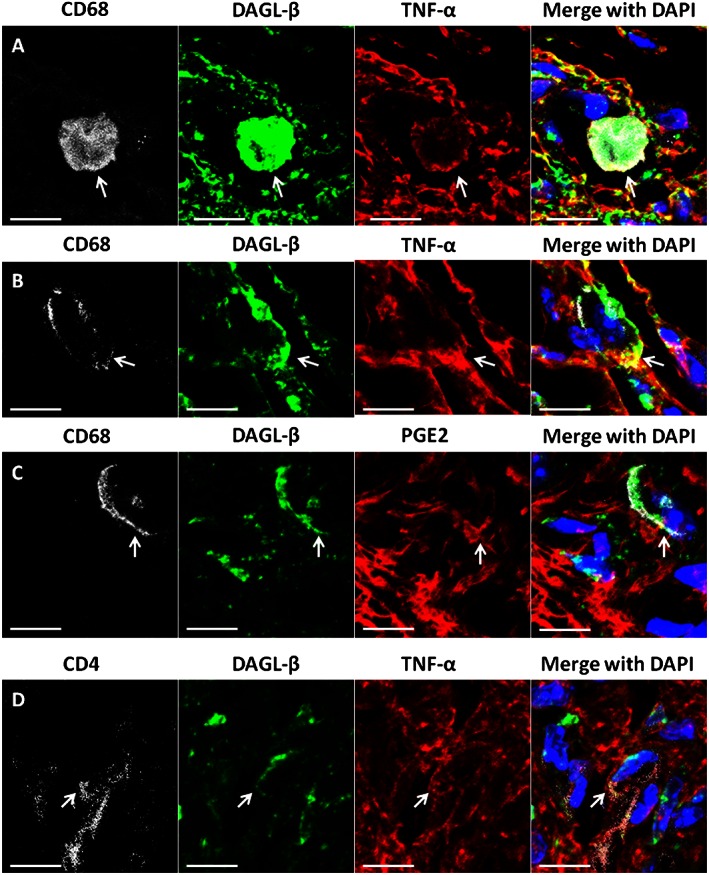

In an initial study, we sought to establish the selectivity of the antibody to DGLβ and to examine whether a local inflammatory insult alters DGLβ expression. Accordingly, DAGL‐β (−/−) and (+/+) mice were given an intraplantar injection of LPS or vehicle. The subjects were killed 24 h later, the paws were harvested and DGLβ immunoreactivity was examined in paw pads. Immunohistochemical orientation of paw pads is shown in Supporting Information Fig. S1. As can be seen in Figure 1, DGLβ immunoreactivity was not present in DAGL‐β (−/−) tissue, indicating the selectivity of the antibody. Strikingly, DGLβ immunoreactivity was significantly greater in LPS‐treated paw pads than vehicle‐injected paw pads from wild‐type mice [interaction between treatment and genotype: F(1,14) = 7.78; P < 0.05]. Within the paw pads of DAGL‐β (+/+) LPS‐treated mice, DGLβ was co‐labelled with CD68/ED1 positive cells (Figure 2A and 2B) and was extensively co‐labelled with TNF‐α on the cellular surface. DGLβ was co‐labelled sparsely with PGE2 on CD68 positive cells (Figure 2C) and was also co‐labelled with TNF‐α in CD4 positive T‐cells within inflamed paw pads, (Figure 2D). Although vehicle‐injected mice expressed DGLβ on CD68 positive cells, TNF‐α and PGE2 were only faintly expressed (Supporting Information Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Qualitative confocal images of cellular immunostaining of DGLβ, TNF‐α and PGE2 in DAGL‐β (+/+) paw pads. (A–D) Paw pad tissue from mice treated with LPS. (A,B) Immunostaining of DGLβ (green) in paw pads is co‐labelled (yellow) with TNF‐α (red) on CD68/ED1 positive (white) cells. DAPI nuclear labelling is blue. Arrows indicate DGLβ and TNF‐α co‐labelling. (C) Immunostaining of DGLβ (green) in paw pads is co‐labelled with PGE2 (red) on CD68/ED1 positive (white) cells, with DAPI nuclear labelling (blue). Arrows indicate co‐labelling of DGLβ and PGE2. (D) Immunostaining of DGLβ (green) in paw pads with TNF‐α (red) on CD4 positive cells, with DAPI nuclear labelling (blue). Arrows indicate co‐labelling of DGLβ and TNF‐α. In all images, the scale bar is equal to 20 μm.

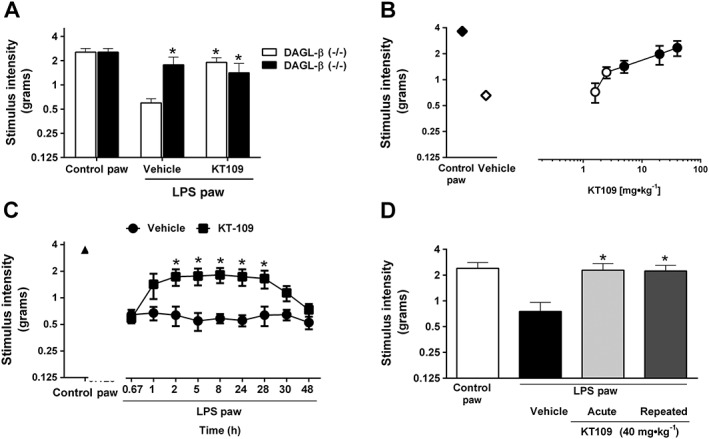

We next examined the nociceptive responses elicited by intraplantar injection of LPS in DAGL‐β (−/−) and (+/+) mice treated with vehicle or KT109 (40 mg·kg−1, i.p.) administered at 22 h. Intraplantar injections of LPS produced significant allodynic responses in the ipsilateral paw compared with the contralateral paw of DAGL‐β (+/+) mice and C57BL/6J mice (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3A, a significant genotype by drug interaction [F(2,70) = 3.531; P < 0.05] was detected. DAGL‐β (−/−) mice were resistant to LPS‐induced allodynia and KT109 reversed allodynia produced by LPS in the DAGL‐β (+/+) mice but had no further actions on mechanical threshold in the DAGL‐β (−/−) mice. KT109 significantly reversed LPS‐induced allodynia in a dose‐related fashion [F(6,56) = 22.98; P < 0.05; Figure 3B]. In contrast, KT109 did not alter normal sensory threshold responses to light touch in the contralateral paw at any dose administered (data not shown). The ED50 value (95% confidence interval) of KT109 in reversing LPS‐induced allodynia was 10.4 (5.3–20.4) mg·kg−1.

Figure 3.

Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of DGLβ blocks LPS‐induced allodynia. (A) LPS‐treated DAGL‐β (−/−) mice do not develop allodynia. KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) reverses LPS‐induced allodynia in wild‐type mice but does not further alter the anti‐allodynic phenotype in DAGL‐β (−/−) mice. n = 13 WT/KO – vehicle groups, n = 14 WT/KO – KT109 groups. (B) KT109 reverses LPS‐induced allodynia in a dose‐dependent manner. For the doses of 1.6, 2.5 and 20 mg·kg−1, n = 5 mice per group, and for the doses of 5, 40 mg·kg−1, n = 6 mice per group. Filled symbols denote P < 0.05 significance from LPS + vehicle. (C) KT109 reversal of LPS‐induced allodynia persists for a long duration of time. n = 6 mice per group. (D) Acute or repeated administration of KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) prevents the expression of LPS‐induced allodynia. For vehicle and acute KT109 groups, n = 5 mice per group, and for the repeated KT109 administration group, n = 6 mice. Data represent mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 versus WT LPS + vehicle. The differences in experimental numbers within these studies reflect an odd number of animals evenly distributed in the experimental design.

The time course of the anti‐allodynic effects of KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) are shown in Figure 3C. The drug significantly reversed allodynia within 2 h of i.p. administration, and this antinociceptive effect persisted for 28 h [interaction between treatment and time: F(8,80) = 73.37; P < 0.05].

In a separate group of mice, we examined whether repeated administration of KT109 would prevent the expression of LPS‐induced allodynia. As shown in Figure 3D, the vehicle group displayed a significant allodynic response to LPS, but acute or repeated administration of KT109 completely prevented the allodynic effects of LPS [F(2,13) = 5.68; P < 0.05].

In order to assess whether crosstalk occurred between KT109 and cannabinoid receptors in altering nociceptive thresholds, the anti‐allodynic effects of KT109 were assessed in LPS‐injected CB1 (−/−) and CB2 (−/−) mice. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S3, KT109 reversed LPS‐induced allodynia in both CB1 (−/−) [main effect of KT109: F(1,20) = 12.26; P < 0.05] and CB2 (−/−) [main effect of KT109: F(1,20) = 16.29; P < 0.05] mice, suggesting that the anti‐allodynic effects of KT109 were independent of cannabinoid receptors. Also, the knockout mice did not differ from their respective wild type control littermates (P = 0.95 and P = 0.23, respectively).

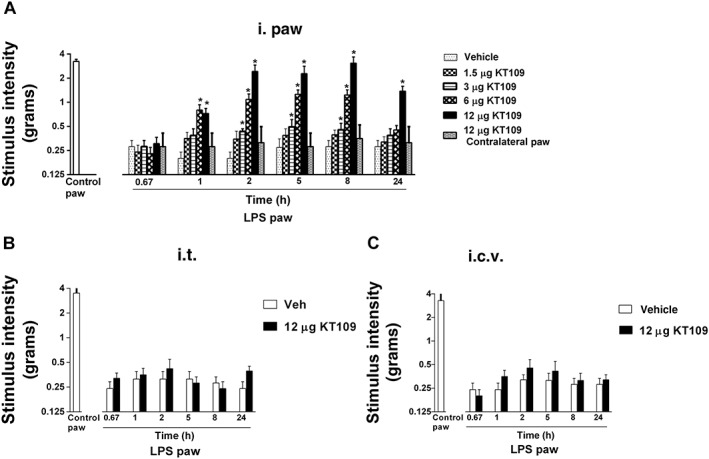

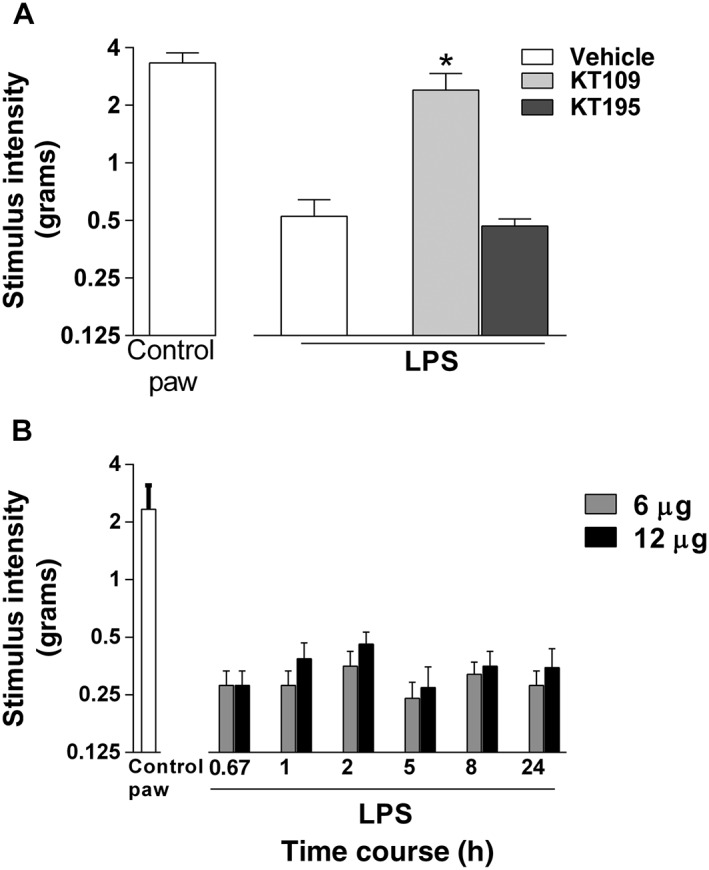

As numerous anatomical sites within the CNS and periphery may mediate the anti‐allodynic effects of systemically administered KT109, we next sought to identify its locus of action. Intraplantar injection of KT109 into the LPS‐treated paw reversed the allodynia in a dose‐related and time‐related fashion (Figure 4A). A two‐way ANOVA revealed a significant KT109 dose by time interaction [F(20,140) = 5.99; P < 0.05]. The 3 and 6 μg doses significantly attenuated allodynia from 1–2 to 8 h. High‐dose KT109 (12 μg) significantly attenuated allodynia from 1 to 24 h, with a full reversal from 2 to 8 h. The ED50 (95% confidence interval) value of KT109 following the intraplantar route of administration was 5.8 (4.2–7.9) μg.

Figure 4.

Locally administered KT109 reverses LPS‐induced allodynia. (A) Intraplantar KT109 reverses LPS‐induced allodynia in a dose‐related manner that persists up to 24 h (P < 0.001). A contralateral injection of 12 μg KT109 does not reverse LPS‐induced allodynia at any time point. (B) KT109 (12 μg) administered i.t. does not reverse LPS‐induced allodynia. (C) KT109 (12 μg) administered i.c.v. does not reverse LPS‐induced allodynia. *P < 0.05 versus LPS + vehicle. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 6 mice per group.

In order to test the possibility that intraplantar administration of KT109 may have produced its anti‐allodynic actions by diffusing through sites outside of the LPS‐treated paw, an additional group of mice was given an intraplantar injection of 12 μg KT109 into the contralateral (i.e. non‐LPS treated) paw. This control group did not display LPS‐induced allodynia at any time point assessed (Figure 4A). Additional studies examined whether central injection of 12 μg KT109 would reverse LPS‐induced allodynia. Neither i.t. (P = 0.70) nor i.c.v. (P = 0.43) injection of KT109 reversed LPS‐induced allodynia at any time point tested (Figure 4B and 4C).

Because KT109 also inhibits ABHD6, we tested whether the structurally related compound KT195, a selective ABHD6 inhibitor, would reverse LPS‐induced allodynia. Systemic administration of KT195 (40 mg·kg−1) 22 h post LPS did not significantly alter LPS‐induced allodynia, whereas 40 mg·kg−1 KT109 fully reversed from allodynia within 2 h post drug injection [F(4,20) = 15.41; P < 0.05] (Figure 5A). To control for possible off‐target ABHD6 effects of local, intrapaw KT109, we tested whether intraplantar injection of KT195 (6 or 12 μg) into the LPS‐treated paw would attenuate the allodynia. As can be seen in Figure 5B, intrapaw KT195 did not significantly alter LPS‐induced allodynia (P = 0.94).

Figure 5.

Selective inhibition of ABHD6 alone does not reverse LPS‐induced allodynia. (A) KT109 (40 mg·kg−1), but not the selective ABHD6 inhibitor KT195 (40 mg·kg−1), reduces LPS‐induced allodynia. (B) Intraplantar injection of (12 μg) does not alter LPS‐induced allodynic thresholds at any time point tested. *P < 0.05 versus LPS + vehicle. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 6 mice per group.

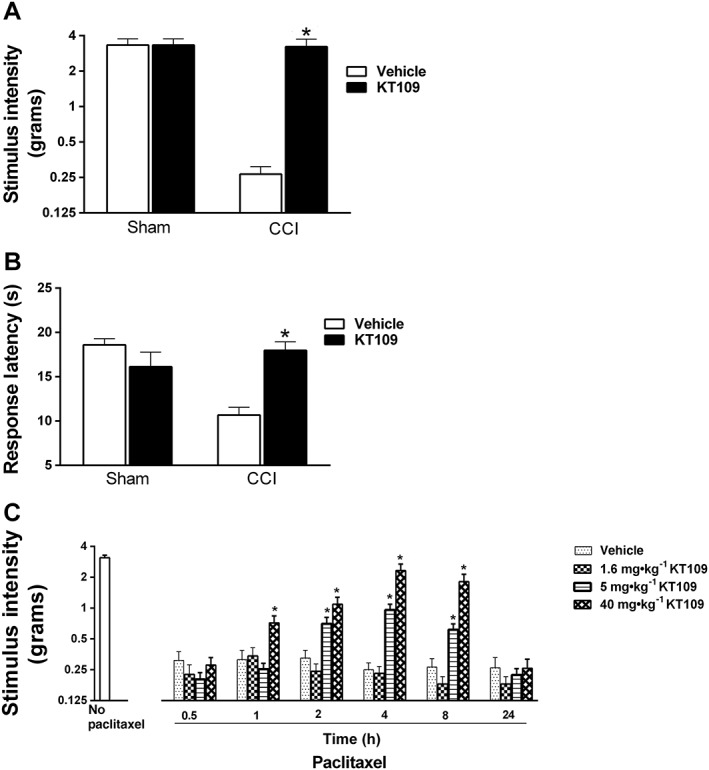

In the next experiments, we assessed whether KT109 produces antinociceptive effects in other models of pathological pain, including the CCI model of neuropathic pain and the paclitaxel model of CINP. A 2 h pretreatment of KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) reversed CCI‐induced allodynia [significant interaction between drug and surgery: F(1,26) = 13.69; P < 0.05; Figure 6A] and thermal hyperalgesia as measured by the hot plate assay [significant interaction between drug and surgery: F(1,26) = 21.75; P < 0.05; Figure 6B]. In contrast, KT109 did not alter normal sensory threshold responses to light touch (Figure 6A) or to heat (Figure 6B) in sham‐operated mice. Likewise, KT109 (5 or 40 mg·kg−1) reversed paclitaxel‐induced allodynia for up to 8 h [F(15,270) = 13.73; P < 0.05; Figure 6C].

Figure 6.

KT109 reverses CCI‐induced allodynia, thermal hyperalgesia and paclitaxel‐induced allodynia. (A) KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) reverses CCI‐induced allodynia, but does not alter threshold responses in sham mice. (B) KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) reverses CCI‐induced thermal hyperalgesia, as assayed in the hot plate test but does not alter responses in sham mice. In these studies, n = 6 mice per group. Data represent mean ± SEM, * P < 0.05 versus CCI + vehicle. (C) KT109 dose‐dependently reverses paclitaxel‐induced allodynia up to 8 h post injection. In these studies, n = 9 mice per group. Data represent mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 versus paclitaxel + vehicle.

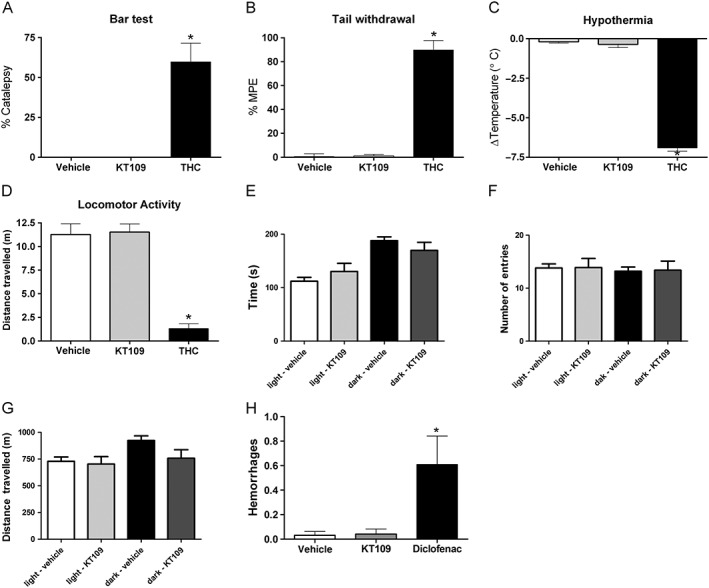

Given that KT109 represents a novel pharmacological tool to inhibit DGLβ, the final set of experiments sought to test potential side effects that might limit clinical viability. To examine whether KT109 produces other overt pharmacological effects, we assessed its effects in the tetrad assay (Little et al., 1988), which consists of catalepsy, hypothermia, thermal hypoalgesia and decreased locomotion and is generally used to screen CB1 receptor agonists. Naïve mice given vehicle, 40 mg·kg−1 KT109 or 30 mg·kg−1 THC (positive control) were tested in the four behavioural assays (Figure 7A–D). KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) did not produce catalepsy, hypothermia (P = 0.44), thermal hypoalgesia (P = 0.79) or hypomotility (defined as time spent immobile; P = 0.86). Conversely, mice treated with THC displayed significant effects in all assays. Next, we assessed whether KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) would alter behaviour in the light/dark assay. As shown in Figure 7E–G, no effects were found on time spent in the light or dark side (P = 0.29), number of entries into either side (P = 0.67) or locomotion (P = 0.30). As KT109 inhibits arachidonic acid formation and concomitant formation of PGs in some tissues (Hsu et al., 2012), we examined if inhibition of DAGL‐β produces gastric hemorrhages. Naïve mice were deprived of food for 24 h and then were given vehicle, 40 mg·kg−1 KT109 or the non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agent diclofenac (100 mg·kg−1), which served as a positive control. Whereas diclofenac produced gastric hemorrhages, vehicle‐treated and KT109‐treated mice showed no evidence of hemorrhages [F(2,22) = 6.20; P < 0.05, Figure 7H].

Figure 7.

KT109 does not produce appreciable untoward side effects. KT109 (n = 5) does not produce catalepsy (A), antinociception in the tail withdrawal test (B), hypothermia (C) or decreases in locomotion (D). The positive control, THC (n = 5, 30 mg·kg−1) was active in each assay. *P < 0.05 versus vehicle (n = 6). The differences in experimental numbers reflect an odd number of animals evenly distributed in the experimental design. KT109 (40 mg·kg−1, i.p.) does not alter behaviour in the light/dark box assay. (E) KT109 does not alter time spent in either the light or the dark side. (F) KT109 does not reduce the distance travelled. (G) KT109 does not change the number of total entries into the light or dark side. n = 10 mice per group, *P < 0.05 versus vehicle + light side. (H) KT109 (40 mg·kg−1, i.p.) does not produce gastric haemorrhages in food‐restricted mice. Mice treated with the COX‐1/2 inhibitor diclofenac sodium (100 mg·kg−1, i.p.) developed gastric haemorrhages. For the vehicle treated group, n = 9 mice, and for the KT109/diclofenac groups, n = 8. Data represent mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 versus vehicle. The differences in experimental numbers reflect an odd number of animals evenly distributed in the experimental design.

Discussion

This study employed complementary pharmacological and genetic approaches to test whether blockade of DGLβ produces antinociceptive effects in the LPS model of inflammatory pain. The selective DGLβ inhibitor KT109 robustly reversed LPS‐induced allodynia following either systemic administration or local injection into the afflicted paw but had no effects when administered i.c.v. or i.t. Additionally, immunostaining of LPS‐treated paw pads revealed increased immunoreactivity of DGLβ and expression of DGLβ on CD68+ monocytes/macrophages that express TNF‐α and PGE2, as well as expression of DGLβ on CD4+ T cells. DGLβ immunoreactivity expression in LPS‐treated paws was substantially higher than its expression under basal conditions, which may have resulted from immune cells already present in the paw tissue or a general increase in cell numbers driven by immune cell extravasation. Additionally, CD68+ cells from control paws expressed DGLβ, in the absence of detectable TNF‐α or PGE2. These observations are consistent with the in vitro findings that DGLβ inhibition reduces TNF‐α and PGs in LPS‐treated peritoneal macrophages (Hsu et al., 2012).

Whereas DGLβ is present in the CNS and periphery, its pharmacological inhibition or genetic deletion results in significant decreases in 2‐AG and arachidonic acid in liver but has no impact on these lipids in whole brain (Hsu et al., 2012). Pharmacological inhibition of DGLβ also reduces both arachidonic acid and 2‐AG in LPS‐stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages (Hsu et al., 2012). Therefore, we tested whether local administration of KT109 into the hindpaw would reverse LPS‐induced allodynia. The findings that KT109 administration into the LPS‐injected paw, but not in the contralateral paw or into the CNS, reversed allodynic responses support a local site of action. Indeed, these findings are consistent with those of Hsu et al. (2012), who reported that KT109 decreased PG levels in LPS‐stimulated peritoneal macrophage. PGE2 and other PGs contribute to the production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines through signalling events initiated by PG binding and subsequent activation of its cognate receptor found on resident and infiltrating T‐cells and monocytes/macrophage (Woodhams et al., 2007; Yao et al., 2009; Endo et al., 2014). These activated immune cells produce additional pro‐inflammatory cytokines and second messenger proteins, which drive inflammation and pathological pain (Schafers et al., 2004; Costigan et al., 2009).

Another relevant finding in the present study is that repeated administration of KT109 (40 mg·kg−1) for 6 days continued to prevent the expression of LPS‐induced allodynia. This apparent lack of tolerance is consistent with the observation that DAGL‐β (−/−) mice displayed an anti‐allodynic phenotype in the LPS model of inflammatory pain. These results taken together suggest that DGLβ inhibitors may represent a class of antinociceptive drugs that do not undergo tolerance after repeated administration, at least in the case of inflammatory pain elicited by endotoxin. It will be important in future studies to ascertain whether repeated KT109 administration also reverses nociceptive behaviour in chronic models of inflammatory or neuropathic pain.

As KT109 also inhibits ABHD6 (Hsu et al., 2012), a serine hydrolase that hydrolyzes 2‐AG but to a much lesser extent than monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL) (Blankman et al., 2007; Marrs et al., 2010), we tested KT195, a structurally similar compound that inhibits ABHD6 without actions at either DGLβ or DGLα (Hsu et al., 2012), in the LPS model of inflammatory pain. Neither systemic (i.p.) nor local (i.paw) injection of KT195 at similar doses as KT109 produced reversal of LPS‐induced allodynia, suggesting that ABHD6 inhibition does not elicit antinociceptive effects in this assay. Further, the anti‐allodynic phenotype of the DAGL‐β (−/−) mice was not altered by KT109, suggesting that KT109 does not have additional off‐target in vivo actions that would produce enhanced anti‐allodynic responses outside of its actions on DGLβ.

Given that these studies represent the first in vivo characterization of a selective DGLβ inhibitor in common mouse models of pain, we assessed KT109 in a battery of in vivo assays to assess potential side effects. Because DAGL‐α (−/−) mice were reported to display increased anxiogenic behaviour in multiple assays used to infer anxiety (i.e. the open‐field, light/dark box and novelty‐induced hypophagia test) (Shonesy et al., 2014), we elected to assess the effects of KT109 in the light/dark assay. KT109 did not alter the duration of time spent on either side, suggesting that it does not elicit anxiogenic or anxiolytic effects. Moreover, we found that KT109 did not produce any observable effects in the tetrad assay, which consists of four distinct in vivo tests (assessment of locomotor activity, catalepsy, thermal antinociception and hypothermia). The lack of KT109 efficacy in this battery of tests is consistent with the idea that it is devoid of CNS effects on behaviour and thermal regulation. Likewise, KT109 reversed allodynia in CB1 (−/−) and CB2 (−/−) mice, showing no apparent cannabinoid receptor involvement. Finally, KT109 did not elicit gastric ulcers in food‐deprived mice, whereas the COX‐1/2 inhibitor diclofenac produced a significant increase in gastric haemorrhages, as previously reported (Kinsey et al., 2011b). Indeed, the high incidence of gastric haemorrhages is a severe limitation of COX inhibitors used for pain relief (Laine, 2002). The lack of gastric side effects of KT109 are consistent with the low expression of DGLβ in stomach (Hsu et al., 2012) and the fact that 2‐AG does not appear to contribute to arachidonic acid or PG formation in gut (Nomura et al., 2011). In contrast, MGL inhibitors inhibit the development of gastric haemorrhages produced by COX inhibitors (Kinsey et al., 2013). Accordingly, the absence of KT109 effects in this cadre of assays suggests that DGLβ inhibition lacks untoward side effects on CNS and gastrointestinal function.

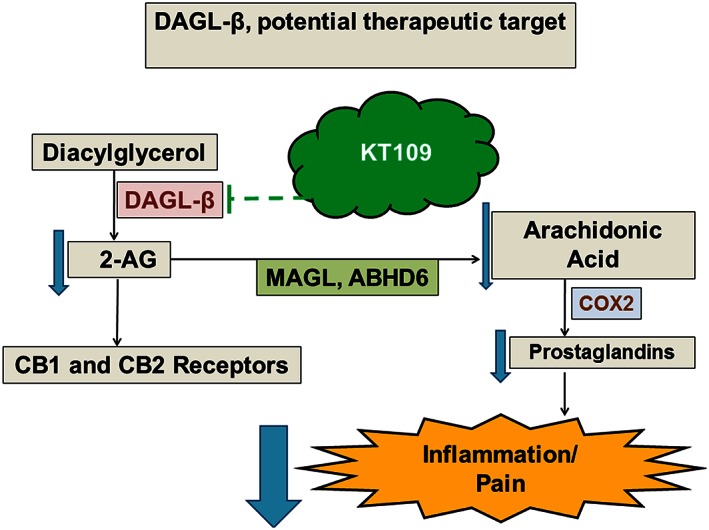

Previous work shows that both MGL and 2‐AG are present and biologically relevant on innate immune cells (Witting et al., 2004; Muccioli et al., 2007; Wilkerson et al., 2012a). Binding of 2‐AG on CB2 receptor expressing immune cells produces anti‐inflammatory actions that also reduce allodynia and hyperalgesia in laboratory rodent models of pathological pain (Buckley et al., 2000; Romero‐Sandoval et al., 2009; Kinsey et al., 2011a; Wilkerson et al., 2012a). Here, we present seemingly paradoxical novel evidence showing that inhibition of the major endocannabinoid biosynthetic enzyme DGLβ that is highly expressed on macrophages reduces nociceptive responses in three mouse models of pain without involvement of the cannabinoid receptors. We suspect that the antinociceptive effects of KT109 are due to its known inhibitory actions on the formation of arachidonic acid and concomitant formation of autocoids, such as PGE2, as well as pro‐inflammatory cytokines (Hsu et al., 2012). Prevention of 2‐AG hydrolysis by MGL inhibition activates a similar protective pathway from neuroinflammatory insults in brain (Nomura et al., 2011). Thus, DGLβ inhibition reflects an approach to reduce inflammatory and neuropathic pain through a cannabinoid receptor dispensable pathway.

KT109 was also effective in the CCI neuropathic pain and paclitaxel CINP models. While distinctly different in aetiology, each of the three nociceptive models used in the present study are known to involve activated immune cells and pro‐inflammatory cytokine activity via activation of the toll‐like receptor 4 (Trebino et al., 2003; Schafers et al., 2004; Hutchinson et al., 2008; Ricciotti and FitzGerald, 2011). These findings reveal that DGLβ inhibitors are efficacious in multiple pathological models of pain. Inhibition of MGL also produces reversal of LPS‐stimulated pro‐inflammatory cytokine release (Kerr et al., 2013) and reverses allodynia and thermal sensitivity in inflammatory (Guindon et al., 2011; Ghosh et al., 2013b), CCI (Kinsey et al., 2009, 2010, 2013) and CINP (Guindon et al., 2013) pain models. Although the anti‐inflammatory and anti‐allodynic effects of MGL inhibitors require cannabinoid receptors, the relative contribution of additional modulation of arachidonic acid metabolites remains unclear. Additionally, given the role of CNS glia and inflammatory events in neuropathic pain models (Wilkerson et al., 2012a, 2012b), the role of central DGLβ in the observed antinociceptive effects of systemic KT109 in neuropathic models has yet to be determined. However, upstream modulation of 2‐AG via DGLβ inhibition probably produces its anti‐allodynic effects through a cannabinoid receptor‐independent mechanism by decreasing arachidonic acid and its metabolites (Hsu et al., 2012), which in turn decreases inflammation and subsequent pain processing (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanism of action for DGLβ inhibition via KT109. KT109 inhibits the degradation of diacylglycerol, limiting the formation of 2‐AG, which does not appear to produce functional alterations at either cannabinoid receptor. Decreased 2‐AG, in turn, leads to lower levels of free arachidonic acid, which results in decreased levels of prostaglandins, and subsequent modulation of inflammation and pain.

Taken together, the results of the present study provide proof of principle that DGLβ inhibition reduces nociceptive behaviour in relevant preclinical models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Moreover, DGLβ inhibition lacked discernible side effects, including gastric ulcer formation, which occurs with COX‐1/2 inhibitors (Laine, 2002), anxiogenic effects, which is a phenotype expressed by DAGL‐ α (−/−) mice, or alterations in motor function or thermoregulation. Finally, the observations that intraplantar LPS led to increased local DGLβ immunoreactivity, which was co‐labelled with PGE2 and TNF‐α on immune cells reveal a potential functional role of this enzyme in contributing to immune cell activation and pro‐inflammatory signalling cascades. Thus, DGLβ inhibition may represent a unique therapeutic strategy to relieve pain elicited by activation of pro‐inflammatory events.

Author Contributions

J.L.W, S.G., D.B., S.G.K., L.E.W., B.F.C. and A.H.L. participated in research design. J.L.W, S.G., D.B., B.F.C. and B.L.M conducted experiments; K.L.H. and B.F.C. contributed new reagents or analytic tools. J.L.W, S.G., D.B., B.L.M. and L.E.W. performed data analysis. J.L.W., D.B., M.I.D., S.G.K., L.E.W. and A.H.L. wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organizations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Figure S1 DAGL‐β staining in paw pad. (A) Image taken at 5× magnification of DAGL‐β fluorescent staining with DAGL‐β antibody in mouse paw tissue, containing paw pad, muscle and connective tissue. Scale bar is equal to 200 μm. (B) Inlay of image outlined in the white box at 5×, taken at 20× magnification. This image shows paw pad tissue, and is representative of the location where paw pad images for DAGL‐β quantitative analysis were taken. Scale bar is equal to 50 μm.

Figure S2 Qualitative confocal images of cellular immunostaining of DAGL‐β, TNF‐α and PGE2 in paw pads from mice with vehicle treatment. (A) Immunostaining of DAGL‐β (green) in paw pads, with TNF‐α (red) on CD68/ED1 positive (white) cells. DAPI nuclear labeling is blue. Arrows indicate DAGL‐β co‐labeling with CD68. (B) Immunostaining of DAGL‐β (green) in paw pads with PGE2 (red) on CD68/ED1 positive (white) cells, with DAPI nuclear labeling (blue). Arrows indicate co‐labeling of DAGL‐β with CD68. In all images the scale bar is equal to 20 μm.

Figure S3 KT109 (40 mg·kg−1, i.p.) reverses LPS‐induced allodynia independently of cannabinoid receptors. KT109 reverses LPS‐induced allodynia in (A) CB1 (−/−) and (+/+) mice as well as in (B) CB2 (−/−) and (+/+) mice. * P < 0.05 vs. LPS + vehicle. Data reflect mean ± SEM, n = 6 mice/group.

Acknowledgements

Research was supported by NIH grants: DA009789, DA017259, DA032933, DA033934‐01A1, DA035864 and DA038493‐01A1. Microscopy was performed at the VCU Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology Microscopy Facility, supported, in part, with funding from NIH‐NINDS Center core grant (5P30NS047463).

Wilkerson, J. L. , Ghosh, S. , Bagdas, D. , Mason, B. L. , Crowe, M. S. , Hsu, K. L. , Wise, L. E. , Kinsey, S. G. , Damaj, M. I. , Cravatt, B. F. , and Lichtman, A. H. (2016) Diacylglycerol lipase β inhibition reverses nociceptive behaviour in mouse models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 1678–1692. doi: 10.1111/bph.13469.

References

- Alexander SPH, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5744–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Xie KY (1988). A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain 33: 87–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, Minassi A, Cascio MG, Ligresti A et al. (2003). Cloning of the first sn1‐DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol 163: 463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankman JL, Simon GM, Cravatt BF (2007). A comprehensive profile of brain enzymes that hydrolyze the endocannabinoid 2‐arachidonoylglycerol. Chem Biol 14: 1347–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker L, Kinsey SG, Abdullah RA, Blankman JL, Long JZ, Ezzili C et al. (2012). The fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitor PF‐3845 acts in the nervous system to reverse LPS‐induced tactile allodynia in mice. Br J Pharmacol 165: 2485–2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley NE, McCoy KL, Mezey E, Bonner T, Zimmer A, Felder CC et al. (2000). Immunomodulation by cannabinoids is absent in mice deficient for the cannabinoid CB(2) receptor. Eur J Pharmacol 396: 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ (2009). Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu Rev Neurosci 32: 1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SP, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y, Blinova K, Romantseva T, Golding H, Zaitseva M (2014). Differences in PGE2 production between primary human monocytes and differentiated macrophages: role of IL‐1beta and TRIF/IRF3. PLoS One 9: e98517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folgosa L, Zellner HB, El Shikh ME, Conrad DH (2013). Disturbed follicular architecture in B cell A disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM)10 knockouts is mediated by compensatory increases in ADAM17 and TNF‐alpha shedding. J Immunol 191: 5951–5958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Vasilyev DV, Goncalves MB, Howell FV, Hobbs C, Reisenberg M et al. (2010). Loss of retrograde endocannabinoid signaling and reduced adult neurogenesis in diacylglycerol lipase knock‐out mice. J Neurosci 30: 2017–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George Paul A, Sharma‐Walia N, Kerur N, White C, Chandran B (2010). Piracy of prostaglandin E2/EP receptor‐mediated signaling by Kaposi's sarcoma‐associated herpes virus (HHV‐8) for latency gene expression: strategy of a successful pathogen. Cancer Res 70: 3697–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, DeCoffe D, Brown K, Rajendiran E, Estaki M, Dai C et al. (2013a). Fish oil attenuates omega‐6 polyunsaturated fatty acid‐induced dysbiosis and infectious colitis but impairs LPS dephosphorylation activity causing sepsis. PLoS One 8: e55468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Wise LE, Chen Y, Gujjar R, Mahadevan A, Cravatt BF et al. (2013b). The monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitor JZL184 suppresses inflammatory pain in the mouse carrageenan model. Life Sci 92: 498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves MB, Suetterlin P, Yip P, Molina‐Holgado F, Walker DJ, Oudin MJ et al. (2008). A diacylglycerol lipase‐CB2 cannabinoid pathway regulates adult subventricular zone neurogenesis in an age dependent manner. Mol Cell Neurosci 38: 526–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon J, Guijarro A, Piomelli D, Hohmann AG (2011). Peripheral antinociceptive effects of inhibitors of monoacylglycerol lipase in a rat model of inflammatory pain. Br J Pharmacol 163: 1464–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon J, Lai Y, Takacs SM, Bradshaw HB, Hohmann AG (2013). Alterations in endocannabinoid tone following chemotherapy‐induced peripheral neuropathy: effects of endocannabinoid deactivation inhibitors targeting fatty‐acid amide hydrolase and monoacylglycerol lipase in comparison to reference analgesics following cisplatin treatment. Pharmacol Res 67: 94–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait NC, Wise LE, Allegood JC, O'Brien M, Avni D, Reeves TM et al. (2014). Active, phosphorylated fingolimod inhibits histone deacetylases and facilitates fear extinction memory. Nat Neurosci 17: 971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A (2001). Targeted gene mutation approaches to the study of anxiety‐like behavior in mice. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 25: 261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KL, Tsuboi K, Chang JW, Whitby LR, Speers AE, Pugh H et al. (2012). DAGLbeta inhibition perturbs a lipid network involved in macrophage inflammatory responses. Nat Chem Biol 8: 999–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MR, Zhang Y, Brown K, Coats BD, Shridhar M, Sholar PW et al. (2008). Non‐stereoselective reversal of neuropathic pain by naloxone and naltrexone: involvement of toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4). Eur J Neurosci 28: 20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti FA, Silvestri C, Mazzarella E, Martella A, Calvigioni D, Piscitelli F et al. (2014). The endocannabinoid 2‐AG controls skeletal muscle cell differentiation via CB1 receptor‐dependent inhibition of Kv7 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E2472–E2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatowska‐Jankowska B, Wilkerson JL, Mustafa M, Abdullah R, Niphakis M, Wiley JL et al. (2015). Selective Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibitors: Antinociceptive versus Cannabimimetic Effects in Mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 353: 424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Urban GM, Wallace M, Ledent C, Jung KM, Piomelli D et al. (2006). Molecular composition of the endocannabinoid system at glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci 26: 5628–5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DM, Harhen B, Okine BN, Egan LJ, Finn DP, Roche M (2013). The monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitor JZL184 attenuates LPS‐induced increases in cytokine expression in the rat frontal cortex and plasma: differential mechanisms of action. Br J Pharmacol 169: 808–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey SG, Long JZ, O'Neal ST, Abdullah RA, Poklis JL, Boger DL et al. (2009). Blockade of endocannabinoid‐degrading enzymes attenuates neuropathic pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 330: 902–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey SG, Long JZ, Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH (2010). Fatty acid amide hydrolase and monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors produce anti‐allodynic effects in mice through distinct cannabinoid receptor mechanisms. J Pain 11: 1420–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey SG, Mahadevan A, Zhao B, Sun H, Naidu PS, Razdan RK et al. (2011a). The CB2 cannabinoid receptor‐selective agonist O‐3223 reduces pain and inflammation without apparent cannabinoid behavioral effects. Neuropharmacology 60: 244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey SG, Nomura DK, O'Neal ST, Long JZ, Mahadevan A, Cravatt BF et al. (2011b). Inhibition of monoacylglycerol lipase attenuates nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug‐induced gastric hemorrhages in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 338: 795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey SG, Wise LE, Ramesh D, Abdullah R, Selley DE, Cravatt BF et al. (2013). Repeated low‐dose administration of the monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitor JZL184 retains cannabinoid receptor type 1‐mediated antinociceptive and gastroprotective effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 345: 492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisiswa L, Osorio C, Erice C, Vizard T, Wyatt S, Davies AM (2013). TNFalpha reverse signaling promotes sympathetic axon growth and target innervation. Nat Neurosci 16: 865–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG (2001). Retrograde inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx by endogenous cannabinoids at excitatory synapses onto Purkinje cells. Neuron 29: 717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine L (2002). The gastrointestinal effects of nonselective NSAIDs and COX‐2‐selective inhibitors. Semin Arthritis Rheum 32: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafourcade M, Elezgarai I, Mato S, Bakiri Y, Grandes P, Manzoni OJ (2007). Molecular components and functions of the endocannabinoid system in mouse prefrontal cortex. PLoS One 2: 709–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little PJ, Compton DR, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Martin BR (1988). Pharmacology and stereoselectivity of structurally novel cannabinoids in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 247:1046–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Okajima K, Murakami K, Harada N, Isobe H, Irie T (1998). Role of neutrophil elastase in stress‐induced gastric mucosal injury in rats. J Lab Clin Med 132: 432–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JZ, Li W, Booker L, Burston JJ, Kinsey SG, Schlosburg JE et al. (2009). Selective blockade of 2‐arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat Chem Biol 5: 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs WR, Blankman JL, Horne EA, Thomazeau A, Lin YH, Coy J et al. (2010). The serine hydrolase ABHD6 controls the accumulation and efficacy of 2‐AG at cannabinoid receptors. Nat Neurosci 13: 951–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, Ben‐Shabat S, Hanus L, Ligumsky M, Kaminski NE, Schatz AR et al. (1995). Identification of an endogenous 2‐monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 50: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muccioli GG, Xu C, Odah E, Cudaback E, Cisneros JA, Lambert DM et al. (2007). Identification of a novel endocannabinoid‐hydrolyzing enzyme expressed by microglial cells. J Neurosci 27: 2883–2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PG, Ramer MS, Borthwick L, Gauldie J, Richardson PM, Bisby MA (1999). Endogenous interleukin-6 contributes to hypersensitivity to cutaneous stimuli and changes in neuropeptides associated with chronic nerve constriction in mice. Eur J Neurosci 11: 2243–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2011). Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura DK, Morrison BE, Blankman JL, Long JZ, Kinsey SG, Marcondes MC et al. (2011). Endocannabinoid hydrolysis generates brain prostaglandins that promote neuroinflammation. Science 334: 809–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno‐Shosaku T, Maejima T, Kano M (2001). Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signals from depolarized postsynaptic neurons to presynaptic terminals. Neuron 29: 729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B, Wang W, Long JZ, Sun D, Hillard CJ, Cravatt BF et al. (2009). Blockade of 2‐arachidonoylglycerol lipase inhibitor 4‐nitrophenyl 4‐(dibenzo[d][1,3]dioxol‐5‐yl(hydroxyl)methyl)piperidine‐1‐carboxylate (JZL184) enhances retrograde endocannabinoid signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331: 591–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP et al. (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D1098–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA (2011). Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 986–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero‐Sandoval EA, Horvath R, Landry RP, DeLeo JA (2009). Cannabinoid receptor type 2 activation induces a microglial anti‐inflammatory phenotype and reduces migration via MKP induction and ERK dephosphorylation. Mol Pain 5: 25–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafers M, Marziniak M, Sorkin LS, Yaksh TL, Sommer C (2004). Cyclooxygenase inhibition in nerve‐injury‐ and TNF‐induced hyperalgesia in the rat. Exp Neurol 185: 160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosburg JE, Blankman JL, Long JZ, Nomura DK, Pan B, Kinsey SG et al. (2010). Chronic monoacylglycerol lipase blockade causes functional antagonism of the endocannabinoid system. Nat Neurosci 13: 1113–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonesy BC, Bluett RJ, Ramikie TS, Baldi R, Hermanson DJ, Kingsley PJ et al. (2014). Genetic disruption of 2‐Arachidonoylglyercol synthesis reveals a key role for endocannabinoid signaling in anxiety modulation. Cell Rep 9: 1644–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Crager SE, Mogil JS (2004). Paclitaxel‐induced neuropathic hypersensitivity in mice: responses in 10 inbred mouse strains. Life Sci 74:2593–2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K et al. (1995). 2‐Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 215: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura AM, Yamazaki M, Hashimotodani Y, Uchigashima M, Kawata S, Abe M et al. (2010). The endocannabinoid 2‐arachidonoylglycerol produced by diacylglycerol lipase alpha mediates retrograde suppression of synaptic transmission. Neuron 65: 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AM, Palma JL, Shea LD (2015). Sponge‐mediated lentivirus delivery to acute and chronic spinal cord injuries. J Control Release 204: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebino CE, Stock JL, Gibbons CP, Naiman BM, Wachtmann TS, Umland JP et al. (2003). Impaired inflammatory and pain responses in mice lacking an inducible prostaglandin E synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 9044–9049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchigashima M, Narushima M, Fukaya M, Katona I, Kano M, Watanabe M (2007). Subcellular arrangement of molecules for 2‐arachidonoyl‐glycerol‐mediated retrograde signaling and its physiological contribution to synaptic modulation in the striatum. J Neurosci 27: 3663–3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson JL, Gentry KR, Dengler EC, Wallace JA, Kerwin AA, Armijo LM et al. (2012a). Intrathecal cannabilactone CB(2)R agonist, AM1710, controls pathological pain and restores basal cytokine levels. Pain 153: 1091–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson JL, Gentry KR, Dengler EC, Wallace JA, Kerwin AA, Kuhn MN et al. (2012b). Immunofluorescent spectral analysis reveals the intrathecal cannabinoid agonist, AM1241, produces spinal anti‐inflammatory cytokine responses in neuropathic rats exhibiting relief from allodynia. Brain Behav 2: 155–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EJ, Walsh FS, Doherty P (2003). The FGF receptor uses the endocannabinoid signaling system to couple to an axonal growth response. J Cell Biol 160: 481–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA (2001). Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signaling at hippocampal synapses. Nature 410: 588–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witting A, Walter L, Wacker J, Moller T, Stella N (2004). P2X7 receptors control 2‐arachidonoylglycerol production by microglial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 3214–3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams PL, MacDonald RE, Collins SD, Chessell IP, Day NC (2007). Localisation and modulation of prostanoid receptors EP1 and EP4 in the rat chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pain 11: 605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Glimcher LH, Aliprantis AO (2008). HCO3−/Cl‐ anion exchanger SLC4A2 is required for proper osteoclast differentiation and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 16934–16939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C, Sakata D, Esaki Y, Li Y, Matsuoka T, Kuroiwa K et al. (2009). Prostaglandin E2‐EP4 signaling promotes immune inflammation through Th1 cell differentiation and Th17 cell expansion. Nat Med 15: 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Fukaya M, Uchigashima M, Miura E, Kamiya H, Kano M et al. (2006). Localization of diacylglycerol lipase around postsynaptic spine suggests close proximity between production site of an endocannabinoid, 2‐arachidonoyl‐glycerol and presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J Neurosci 26: 4740–4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino H, Miyamae T, Hansen G, Zambrowicz B, Flynn M, Pedicord D et al. (2011). Postsynaptic diacylglycerol lipase mediates retrograde endocannabinoid suppression of inhibition in mouse prefrontal cortex. J Physiol 589: 4857–4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 DAGL‐β staining in paw pad. (A) Image taken at 5× magnification of DAGL‐β fluorescent staining with DAGL‐β antibody in mouse paw tissue, containing paw pad, muscle and connective tissue. Scale bar is equal to 200 μm. (B) Inlay of image outlined in the white box at 5×, taken at 20× magnification. This image shows paw pad tissue, and is representative of the location where paw pad images for DAGL‐β quantitative analysis were taken. Scale bar is equal to 50 μm.

Figure S2 Qualitative confocal images of cellular immunostaining of DAGL‐β, TNF‐α and PGE2 in paw pads from mice with vehicle treatment. (A) Immunostaining of DAGL‐β (green) in paw pads, with TNF‐α (red) on CD68/ED1 positive (white) cells. DAPI nuclear labeling is blue. Arrows indicate DAGL‐β co‐labeling with CD68. (B) Immunostaining of DAGL‐β (green) in paw pads with PGE2 (red) on CD68/ED1 positive (white) cells, with DAPI nuclear labeling (blue). Arrows indicate co‐labeling of DAGL‐β with CD68. In all images the scale bar is equal to 20 μm.

Figure S3 KT109 (40 mg·kg−1, i.p.) reverses LPS‐induced allodynia independently of cannabinoid receptors. KT109 reverses LPS‐induced allodynia in (A) CB1 (−/−) and (+/+) mice as well as in (B) CB2 (−/−) and (+/+) mice. * P < 0.05 vs. LPS + vehicle. Data reflect mean ± SEM, n = 6 mice/group.