Abstract

Background: Informal caregivers play a critical role in the provision of care to hospice patients. The care they provide often impacts their physical and psychological well-being.

Objective: This study synthesized 58 articles pertaining to informal hospice caregiving, focusing on caregivers' satisfaction with hospice services, the physical and psychological well-being of caregivers, the predictors of caregivers' well-being, the direct impact of hospice services on caregivers, and the effectiveness of targeted interventions for hospice caregivers.

Method: A systematic literature review of journal articles published between 1985 and 2012 was conducted.

Results: The studies reviewed found hospice caregivers to experience clinically significant levels of anxiety, depression, and stress; however, results for caregiver burden and quality of life were mixed. Caregivers' perceptions regarding the meaningfulness of care as well as their levels of social support were associated with enhanced psychological outcomes.

Conclusions: Beyond satisfaction with hospice services, the direct impact of standard hospice care on caregivers remains uncertain. Caregiver intervention studies have demonstrated promising outcomes signifying a need for additional investigations into hospice-specific interventions that improve caregiver outcomes. Additional research and resources are needed to assist hospice caregivers, with the ultimate goal of minimizing their psychiatric and physical morbidity and enhancing their caregiving and subsequent bereavement processes.

Introduction

Patients with life-limiting illness often wish to remain at home versus being admitted to a hospital, shifting caregiving responsibilities from formal or institutional caregivers to informal caregivers.1–3 Family and friends as informal or unpaid caregivers provide an average of 66 hours per week of physical, emotional, and practical care during the last year of a loved one's life.4,5 In the United States over 70% of patients with life-limiting illness receive care from an informal caregiver at the time of their death, and an estimated three million informal caregivers accompany hospice patients through the dying process annually.6 The care provided by family and friends represents considerable economic value to the health care system.2,3,5 However, providing care to a loved one during the dying process involves significant personal, professional, and financial sacrifices,6,7 and consequently should also be viewed in terms of its personal and societal costs.

Unfortunately, providing care to a family member or loved one at the end of life has also been associated with detrimental effects on caregivers' physical and psychological well-being8–14 and increased risk of mortality.12,15–17 Furthermore, the well-being of caregivers and patients are intimately linked. For example, caregivers' well-being often deteriorates as the burden and stress of caregiving increases, putting the patient at increased risk of hospitalization.11,18,19 Also, psychological distress within a caregiver-patient dyad is correlated, suggesting that the caregiver and patient are interdependent and respond to distress as a unit.9,20 As caregivers typically survive beyond the patient, reducing psychological and physical morbidity in these individuals has a long-term impact both on their well-being and their bereavement process after the death of the patient.11,12,21 For hospice care to be most effective and speak to this public health issue, hospice services must address the needs and stressors associated with informal caregiving.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to review the published research on informal hospice caregivers that evaluated the psychological and physical effect of providing care, the impact of hospice care on caregivers, and the effectiveness of hospice-based interventions for improving caregivers' well-being. Since hospice care is defined differently throughout the world, this review focuses exclusively on caregivers of hospice patients within a U.S. context. The objective of this review is to address the following questions:

1) What is the psychological and/or physical well-being of informal caregivers who provide care to a dying family member or friend enrolled in a U.S. hospice program?

2) Do hospice services have an effect on caregivers' well-being?

3) Do hospice-based caregiver interventions enhance informal caregivers' well-being?

Methods

Design

This study systematically identified and evaluated quantitative and qualitative research on informal hospice caregivers and employed a narrative approach to data synthesis. This approached was selected because of the broad research questions and the diversity of study designs.22 A narrative synthesis was used to assimilate the evidence from the identified studies. This synthesis involved comparing and contrasting the individual studies to identify relevant themes as well as factors that may account for the variability in the results.23

Data sources

Studies from peer-reviewed medical and psychological journals were extracted by searching three electronic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. Searches were conducted by the first author and were limited to studies in English published between January 1985 and December 2012. The following keywords/MeSH search terms were utilized: hospice, caregivers, satisfaction (personal), stress (psychological), caregiver burden, dependency (psychological), well-being, quality of life, health (status), and mental health.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were evaluated by two independent reviewers (first and fourth authors) based on an a priori set of criteria; discrepancies in study ratings were settled by a third independent rater (second author). These were the criteria:

(1) The articles defined an informal caregiver as an individual who provided physical and/or supportive care to a hospice patient, and that care was not provided as part of employment.

(2) The articles provided a clear description of the methods and results.

(3) The articles measured outcomes of caregivers' emotional and/or psychological/psychiatric well-being, physical health, or satisfaction.

Because hospice care in the United States involves unique admission criteria and prescribes a core set of services, only caregivers involved in a U.S. hospice program were included. Self-reports, case studies, editorials, as well as studies not published in English were excluded.

Results

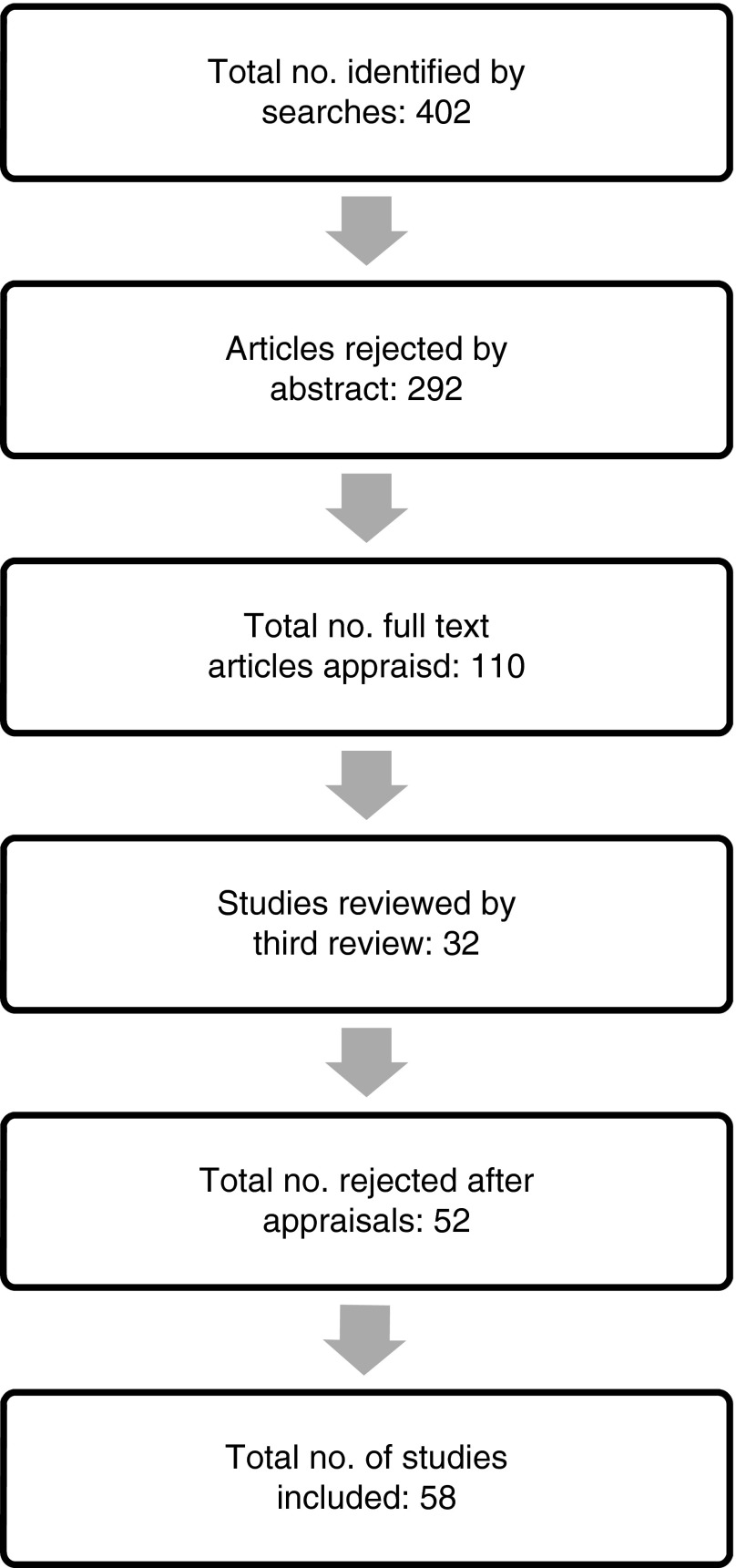

Database searches generated 402 articles (see Fig. 1). Abstracts of these articles were reviewed and 292 articles were rejected based on the a priori criteria. The primary reasons for rejection included inadequate caregiver outcomes, a lack of hospice involvement, and participants not receiving services within the United States (i.e., international studies). The complete texts of the remaining 110 articles were evaluated. Of these, 52 were excluded for not clearly distinguishing between palliative care and hospice care, for using single measurement designs, for reporting change based on mean scores without consideration of variability, and/or for not adequately reporting caregiver outcomes. The remaining 58 articles were included in this review.

FIG. 1.

Decision process for inclusion of informal hospice caregiver articles in the review.

Design and quality of reviewed studies

Key methodological features of the studies included in this review are summarized in Table 1. The most common study design (22 studies) was a descriptive quantitative design.24–29 The next most commonly employed were a prospective quasi-experimental design (15 studies) and a retrospective quasi-experimental design (6 studies).30–36 Qualitative methodology was employed in 11 studies,9,11,37–39 and 3 studies employed a randomized controlled trial.40–42 A few studies were secondary analyses of existing data.16,28

Table 1.

Key Methodological Features of the Studies Included in this Review of Informal Caregiving for Hospice Patients

| Study (reference) | Sample sizea | Percent female; race | Primary disease type; data collection points pre/post patient death | Research design | Response rate (%) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archer & Boyle, 1999 (24) | 44 | 59% 82% Caucasian, 18% African American |

NR Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 80 | Caregiver satisfaction on Primary Caregiver Satisfaction Survey |

| Bernard & Guarnaccia, 2002 (43) | 213 | 29% 92% Caucasian, 8% Other |

Breast cancer Pre & post death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | NR | Grief Experience Inventory and Despair Subscale |

| Bernard & Guarnaccia, 2003 (30) | 213 | 29% NR |

Breast cancer Pre & post death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | NR | Grief Experience Inventory and Despair Subscale |

| Bialon & Coke, 2012 (10) | 9 | 78% 67% Caucasian, 22% African American |

Mixed Post death |

Qualitative | NR | Caregiver interviews |

| Cagle & Kovacs, 2011 (37) | 69 | 72% 84% Caucasian, 4% African American, 11% Other |

Cancer Pre & post death |

Qualitative, prospective | 26 | Survey responses |

| Casarett, Hirschman, Crowley, Galbraith, & Leo, 2003 (52) | 112 | 77% 69% Caucasian, 27% African American, 4% Other |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 54 | Satisfaction with services |

| Chentsova-Dutton, et al., 2000 (32) | 181/112 | 79% 96% Caucasian, 1% African American, 4% Hispanic |

NR Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, retrospective | NR | Depression (BDI, Hamilton Psychiatric Rating Scale for Depression); Psychological symptomatology (BSI); Health (self-rating estimates, medical visits); Social functioning (Social Support Questionnaire) |

| Chentsova-Dutton, et al., 2002 (49) | 84/48 | 83% 96% Caucasian, 2% African American, 2% Hispanic |

NR Pre & post death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | 44 | Depression (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression); Psychological symptomatology (BSI); Grief (Texas Revised Instrument of Grief) |

| Christakis & Iwashyna, 2003 (44) | 61,676 | 80% 93% Caucasian, others NR |

Mixed Post death |

Quasi-experimental, retrospective, matched control group | 100 | Duration of survival of bereaved widows/widowers |

| Dawson, 1991 (54) | 100 | 66% 95% Caucasian, others NR |

NR Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 58 | Three satisfaction measures |

| Demiris, Oliver, Courtney, & Day, 2007 (74) | 12 | 75% NR |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | NR | Anxiety (State Trait Anxiety Inventory) |

| Demiris et al., 2010 (33) | 23 | 76% 86% Caucasian, 1% African American, 13% Other |

NR Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | 89 | Quality of life (CQLI-R); Anxiety (State Trait Anxiety Inventory) |

| Demiris, Oliver, Wittenberg-Lyles, & Washington, 2011 (31) | 33 | 81% 98% Caucasian, 2% African American |

NR Pre death |

Quasi-experimental | 79 | CQLI-R; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Problem-Solving Inventory |

| Demiris, et al., 2012 (41) | 89 | 79% 87% Caucasian |

Pre death | Experimental, prospective | 71 | CQOLI-R; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Problem-Solving Inventory |

| Empeño, Raming, Irwin, Nelesen, & Lloyd, 2011 (77) | 123 | 82% NR |

NR Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | 43 | Pearlin Role Overload Measure |

| Evans, Cutson, Steinhauser, & Tulsky, 2006 (55) | 18 | 50% 61% Caucasian, 39% African American |

NR Post death |

Qualitative, retrospective | 22 | Caregivers' experiences extracted from semi-structured interviews |

| Fenix et al., 2006 (68) | 175 | 75% NR |

NR Most (63%) post death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | 53 | Major Depressive Disorder (SCID) |

| Ganzini, Johnston, & Silveira, 2002 (25) | 50 | NR NR |

ALS Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | NR | Satisfaction with care (FAMCARE) |

| Gill, Kaur, Rummans, Novotny, & Sloan, 2003 (59) | 57 | 68% NR |

NR Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | NR | CQOL (multidimensional measurement) |

| Goldstein, et al., 2004 (26) | 206 | 71% 96% Caucasian, 3% African American, 1% Other |

Cancer Most post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 53 | Caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Inventory) |

| Goy, Carter, & Ganzini, 2008 (27) | 47 | 77% 92% Caucasian, 8% Other |

Parkinson's Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 39 | Caregiver mood (CES-D); Caregiver satisfaction with care |

| Haley, LaMonde, Han, Burton, & Schonwetter, 2003 (34) | 80 | 79% NR |

Lung cancer & dementia Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, retrospective | NR | Caregiver depression (CES-D); Life Satisfaction Index |

| Haley, LaMonde, Han, Narramore, & Schonwetter, 2001 (57) | 120 | 83% 82% Caucasian, 18% Other |

Lung cancer & dementia Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, retrospective | NR | Caregiver depression (CES-D); Life Satisfaction Index; Caregiver physical health (Health Perception Scale & Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey) |

| Herth, 1993 (38) | 25 | 76% NR |

Mixed (cancer most common) Pre death |

Qualitative and quantitative; descriptive, prospective | NR | Hope (Herth Hope Index and semi-structured interview) |

| Holtslander & McMillan, 2011 (28) | 280 | 76% 97% Caucasian, 3% African American, 1% Other |

Cancer Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | NR | Depressive symptoms (CES-D); grief (Texas Revised Inventory of Grief); (Inventory of Complicated Grief) |

| Hull, 1990 (79) | 14 | 79% NR |

NR Pre & post death |

Qualitative descriptive, prospective | NR | Caregiver stressors (interviews) |

| Jones, 2010 (64) | 388 | NR NR |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | NR | Utilization of bereavement services |

| Kilbourn, et al., 2011 (73) | 19 | 91% NR |

NR Pre death |

Quantitative descriptive, prospective | NR | CES-D; PSS; MOS SF-36; ENRICHD Social Support Inventory Benefit Finding Scale |

| Kramer, Kavanaugh, Trentham-Dietz, Walsh, & Yonker, 2010 (71) | 152 | 80% 97% Caucasian, 3% African American |

Lung cancer Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 47 | Complicated grief (Inventory of Complicated Grief) |

| Kreling, et al., 2010 (39) | 30 | NR 50% Caucasian, 50% Hispanic |

NR Post death |

Qualitative design, retrospective | NR | Caregivers' experience of hospice (interviews) |

| Kris, et al., 2006 (50) | 175 | 75% NR |

Cancer Pre and post death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | 53 | Major Depressive Disorder (SCID) |

| Kutner, et al., 2009 (61) | 36 | 86% 92% Caucasian |

NR Post death |

Qualitative design, retrospective | NR | Hospice caregivers' needs (interviews) |

| Kwak, Salmon, Acquaviva, Brandt, & Egan, 2007 (76) | 926 | 81% 88% Caucasian, 7% African American |

NR Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | 46 | Comfort with caregiving tasks; Completion and closure; Caregiving gain (Comfort with Caregiving Scale, Caregiver Closure Scale, CSS) |

| McMillan, 1996 (46) | 118 | 64% NR |

Cancer Pre death |

Quasi -experimental, prospective | NR | Caregiver quality of life (CQOLI) |

| McMillan, et al., 2006 (40) | 354 | 85% NR |

Cancer Pre death |

Experimental | 31 (completed all measures) | Quality of life (CQOL-C); Caregiver burden due to patient symptoms (MSAS); Caregiver burden due to tasks (CDS); Caregiver mastery (6-item scale) |

| McMillan & Mahon, 1994 (66) | 130 | 85% NR |

Cancer Pre death |

Quasi- experimental, prospective | NR | Caregiver quality of life (CQLI) |

| McMillan, Small, & Haley, 2011 (42) | 716 | 74% NR |

Cancer Pre death |

Experimental, prospective | 48% | CES-D; Spiritual Needs Inventory; Mental Status Questionnaire |

| Meyers & Gray, 2001 (53) | 44 | 75% 91% Caucasian, 1% African American, 8% Other |

Mixed (66% cancer) Pre death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 94 | Satisfaction with hospice care (FAMCARE Scale); Quality of life CQOLC; Burden (Caregiver Strain Index) |

| Mickley, Pargament, Brant, & Hipp, 1998 (69) | 92 | 78% NR |

NR Pre death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 37 | Depression (CES-D); Anxiety (BAI); Meaning (Purpose in Life Test); Situational Outcomes (General and Religious Outcome Scales) |

| Moody & McMillan, 2003 (65) | 162 | 78% 85% Caucasian, 11% African American 6% Hispanic, 1% Other |

Cancer (mixed cancer types) Pre death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 54 | Caregiver quality of life |

| Newton, Bell, Lambert, & Fearing, 2002 (62) | 33 | 73% NR |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Pre death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 33 | Needs and concerns of caregivers (interview) |

| Parker, et al., 2010 (75) | 24 | 77% 97% Caucasian |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Pre death |

Quasi- experimental, prospective | 39 | Caregiver quality of life (CQLI-R) |

| Prigerson et al., 2003 (58) | 205 | 71% NR |

Cancer Pre death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 61 | Caregiver fear and helplessness associated with exposure to death (SCARED scale) |

| Redinbaugh, Baum, Tarbell, & Arnold, 2003 (80) | 31 | 68% 84% Caucasian, 16% African American |

Cancer Pre death |

Quantitative Descriptive, retrospective | 54 | Caregiver strain (BSI, Caregiver Burden Screen) |

| Salmon, Kwak, Acquaviva, Brandt, & Egan, 2005 (36) | 953 | 77% NR |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Pre post death |

Quasi-experimental, retrospective | 32 | Caregiver gain; Caregiver burden (Revised Caregiving Appraisal Scale) |

| Speer, Robinson, & Reed, 1995 (67) | 160 | 75% NR |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 30 | Caregiver adjustment (Texas Inventory of Grief) |

| Steele, Mills, Long, & Hagopian, 2002 (56) | 443 | NR | NR Post death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | NR | Satisfaction with hospice services (created scale) |

| Tang, 2009 (29) | 60 | 65% 97% Caucasian, 3% African American |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Pre death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 71 | Caregiver quality of life (CQOLC) |

| Tilden, Tolle, Drach, & Perrin, 2004 (70) | 1189 | 71% NR |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Post death | Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | 72 | Caregiver strain (4 items) |

| Townsend, Ishler, Shapiro, Pitorak, & Matthews, 2010 (63) | 162 | 80% 86% Caucasian, 12% African American, 1% Hispanic, 1% Other |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Pre death |

Quantitative descriptive, retrospective | NR | Caregiver strain (13-item scale) |

| Waldrop & Meeker, 2011 (11) | 3 | 81% 94% Caucasian, 3% African American, 3% Hispanic |

Mostly Cancer Post death |

Qualitative retrospective | 32% | Caregiver interview |

| Weitzner, McMillan, & Jacobsen, 1999 (45) | 401 | 78% 70% Caucasian, 19% African American 9% Hispanic, 2% Other |

Cancer Pre death |

Quasi-Experimental, retrospective | NR | Caregiver quality of life (CQOLC) |

| Wilder, Oliver, Demiris, & Washington, 2008 (35) | 76 | 63% 96% Caucasian, 3% African American, 1% Other |

Mixed (predominantly cancer) Pre death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | NR | Caregiver quality of life (CQLI-R) |

| Wittenberg-Lyles, Demiris, Oliver, & Burt, 2011 (60) | 30 | 77% 97% Caucasian, 3% African American |

Mixed (not predominantly cancer) Pre death |

Qualitative, retrospective | NR | Caregivers' concerns (interviews) |

| Wittenberg-Lyles, et al., 2012 (9) | 81 | 79% 96% Caucasian |

Mixed Pre death |

Qualitative retrospective | NR | Caregivers' concerns (interviews) |

| Wright, et al., 2008 (48) | 332 | 77% 65% Caucasian, 17% African American 16% Hispanic, 2% Other |

Cancer Pre and post death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | 70 | Caregivers' bereavement adjustment (SCID, McGill Quality of Life psychological subscale) |

| Wright, et al., 2010 (72) | 342 | 75% 64% Caucasian, 20% African American 15% Hispanic, 1% Other |

Cancer Pre and post death |

Quasi-experimental, prospective | 72 | Caregivers' mental health (SCID, Prolonged Grief Disorder scale) |

| York, Churchman, Woodard, Wainright, & Rau-Foster, 2012 (51) | 243 | 48% 95% Caucasian |

Mostly cancer Post death |

Qualitative prospective | NR | Free text comments by caregivers |

Total number of participants in study/number of hospice caregivers in study.

ALS, amyolateral sclerosis; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CDS, Caregiver Demands Scale; CES-D, Center for the Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; CQLI-R, Caregiver Quality of Life Revised; CQOLC, Caregiver Quality of Life Index – Cancer; CSS, Caregiver Satisfaction Scale; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th ed; ENRICHD, Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease; FAMCARE, Family Satisfaction with Advanced Cancer Care Scale; MOS; SF-36, Medical Outcome 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; MSAS, Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale; NR, not reported; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SCARED, Stressful Caregiving Adult Reactions to Experiences of Dying scale; SCID, Structered Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

Most of the included studies used non-representative samples of caregivers predominantly of cancer patients. Participants in the included studies were primarily female (with two exceptions30,43) and Caucasian (with one exception39). When reported, participant response varied significantly from a low of 22% to 94%. Few studies reported non-respondent data, making it difficult to exclude selection bias.

The nature and quality of the outcome measures used by the studies varied greatly. Only one study used a biological marker of well-being (mortality),44 with most studies using either previously validated self-report measures or satisfaction questionnaires unique to the specific study. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index – Cancer,45 Caregiver Quality of Life Index – Revised,46 and the CES-D47 were the most commonly used self-report measures. The majority of studies evaluated caregiver outcomes prior to the death of the patient. However, a few studies took a broader perspective on caregiving and assessed caregiver outcomes both before and after the death of the patient.30,37,48–50

Synthesis of studies

Synthesis of the included studies showed them to fall into five main groups: (1) caregivers' satisfaction with hospice services, (2) caregivers' well-being, (3) predictors of caregivers' psychological or physical well-being, (4) the impact of hospice services on caregiver outcomes, and (5) the effectiveness of hospice-based caregiver interventions.

Caregivers' satisfaction with hospice services

These studies measured caregiver satisfaction after the death of the patient and found the majority of caregivers to be satisfied or very satisfied with hospice care and services.24,27,39,48,51–56 Caregivers of hospice patients reported fewer unmet needs when compared with caregivers of patients who died in traditional hospital settings.54 In general, caregiver characteristics (i.e., ethnicity, gender, age, relationship with patient) were not found to be associated with caregiver satisfaction.24,52 Factors associated with higher levels of caregiver satisfaction included time spent with the patient, clear goals of care, personalized treatment plans, accessibility and continuity of hospice staff, effective symptom management, and good communication between hospice staff and caregivers.51,52,55

While level of caregiver satisfaction was not found to be associated with caregiver ethnicity, other group differences were reported between Caucasian and Latino caregivers. Caucasian caregivers access hospice services at a greater rate than Latino caregivers and the locus of decision making differs (family versus individual). Critically identified were the need for culturally specific language and improved cultural literacy among medical providers serving Latino communities.39

Caregivers' well-being

Studies in this category reported on one or more aspects of caregiver well-being. Primary caregiver outcomes included mood and anxiety symptoms, complicated grief, self-reported physical health, and quality of life. Anxiety and depressive symptoms as well as caregiver stress were found to be clinically significant in caregivers of hospice patients both while actively providing care and within the first few months after the death of the patient.9,11,28,30,32,49,57,58 Caregiver quality of life outcomes were mixed. A few studies reported that caregivers' quality of life was relatively healthy or at least adequate,35,59 while others reported caregivers' quality of life was lower than in noncaregiving adults.10,46,57

Subjective indicators of physical health were found to be lower in caregivers at time of hospice enrollment compared with non-caregiving adults.57 As the death of the patient approached, caregivers' quality of life was found to decline, and the demands of providing care substantially increased.10,11,35,38,59

Several studies identified caregivers as “second order patients”60 in need of instrumental and emotional support as well as specialized education in the areas of understanding/interpreting patient symptoms, pain management, and emotional preparation for the patient's death.10,37,58,60–62

Predictors of caregivers' psychological or physical well-being

Studies in this category investigated the impact of caregiver characteristics (e.g., age, gender, health, and religiosity); patient factors (diagnosis and duration of caregiving); caregivers' cognitive appraisals; and social support on caregiver outcomes such as grief, burden, depression, and quality of life. Results for several of the predictors were equivocal. Some studies found specific patient diagnoses (i.e., neurologic disease) predictive of poorer caregiver outcomes,53,63,64 while one study that compared two matched groups of caregivers (lung cancer and dementia) found no difference in depression and life satisfaction.57 A few studies found female gender predictive of higher levels of depression and less life satisfaction,34,57 while others reported caregiving daughters experienced less grief and burden than spousal caregivers.30,53 Increased caregiver age predicted less caregiving burden and strain,26,63 higher quality of life,65 and less complicated bereavement.30 Conversely, some studies found no significant relationship between caregivers' age, gender, and quality of life66 or between quality of life and whether the caregiver was a spouse or daughter of the care receiver.67

Health status, religiosity, social connections, and cognitive appraisal emerged as more reliable predictors of caregiver outcomes. Poor self-reported caregiver health status predicted higher levels of depression, less life satisfaction, and a more intensive grief response.29,30,34,45 Greater religiosity among caregivers on the other hand predicted fewer incidents of Major Depressive Disorder 13 months after the death of the patient.68 Limited social networks and restricted daily activities predicted increased burden, higher levels of depression, and less life satisfaction in active caregivers.26,34,36,63 One of the most consistent findings was the importance of caregivers' subjective appraisals or perception of burden. Caregivers who appraised caregiving demands as less stressful and/or who found meaning and benefit in caregiving experienced lower levels of depression and strain and higher levels of life satisfaction.26,34,36,63,69

Impact of hospice services on caregiver outcomes

This category of studies examined the impact of hospice services on caregiver mortality, psychiatric symptoms, burden, quality of life, and complicated or prolonged grief. A large retrospective study found hospice use decreased the risk of mortality for the surviving spouse, but only for women.44 However, enrollment in hospice was not found to reduce caregiver burden,70 to improve the quality of life for caregivers,48,66 or to be predictive of bereavement adjustment.67

Although hospice care was not a direct predictor of caregiver quality of life, receiving hospice services for at least a week predicted higher patient quality of life; improved patient quality of life was in turn associated with better caregiver quality of life.48,66 Enrollment in hospice services was found to reduce the risk of Major Depressive Disorder following the patient's death50 and also reduce the number of complicated grief symptoms.71 When comparing hospice caregivers to those in other settings, a patient's death in hospice care as opposed to traditional hospital deaths resulted in a decreased risk for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and prolonged grief in caregivers.72

Effectiveness of hospice-based caregiver interventions

This emerging group of studies developed and tested the effectiveness of caregiver interventions delivered within a hospice setting. Findings suggested brief caregiver interventions can be delivered successfully31,41,42,73 and that technology (i.e., videophones and telephones) could improve communication between the hospice team and caregivers, thereby enabling greater participation in care decisions.31,41,74,75

Two pilot studies tested psychosocial caregiver interventions (problem solving) delivered via videophone and telephone and failed to find significant intervention effects.33,73 Nevertheless, a subsequent randomized control trial of a problem solving intervention offered to caregivers via videophone was found to reduce caregiver anxiety and improve problem solving skills, but had no effect on caregivers' quality of life.31 A comparison study of face-to-face and videophone delivery of a problem solving caregiver intervention found no significant difference in caregiver outcomes between the two methods of intervention delivery,41 suggesting a role for this technology in hospice care.

In a randomized control trial by McMillan et al., caregivers of cancer patients were found to significantly benefit (as measured by improved quality of life and reduced burden) from a brief three-session manualized psychosocial intervention.40 This nine-day (three-visit) intervention, labeled Creativity, Optimism, Planning, and Expert Information (COPE), adapted strategies from the problem-solving research literature to address the needs and issues faced by families caring for persons with cancer. Another psychosocial intervention study used a targeted intervention to enhance the positive aspects of caregiving (meaning, purpose, and value in the caregiving experience), improving caregivers' comfort with caregiving tasks and facilitating emotional closure with the patient.76 Results from this nine-session (7.5 hour) intervention found enhanced caregiver perceptions of the positive aspects of caregiving, comfort, and closure.

A second randomized controlled trial by McMillan et al.42 tested the effect of providing brief feedback from standardized psychosocial assessments of patient/caregiver dyads at interdisciplinary hospice team meetings. Results were encouraging for patients, but no change was detected in the caregiver outcomes of depression or spiritual needs. Interventions may also include tangible supports, e.g., caregiving assistance, transportation, cleaning, meal preparation. Providing these additional supports to hospice caregivers was found to reduce caregiver stress and inpatient stays when compared with hospice caregivers not receiving these supplementary services.77

Discussion

In this review of the literature regarding informal caregiving of hospice patients, several important themes emerged. First, caregivers were found to be generally satisfied with hospice services. Clear goals of care, good communication between hospice staff and caregivers, and additional time spent with patients and families promoted higher levels of satisfaction with hospice services. Second, caregivers were found to have clinically significant levels of anxiety, depression, and perceived stress as well as poorer physical health and decreased quality of life when compared with non-caregivers. Third, when attempting to predict caregiver strain, it was found that lowered social support and worsened physical health could be related to increased depression, grief, burden, and diminished life satisfaction. Conversely, increased age, religiosity, and a self-perception about the benefits and meaning of caregiving appeared to have positive and protective effects.

Hospice care in general was not proven in these studies to reduce caregiver burden, improve caregiver quality of life, or assuage the bereavement process. However, the use of hospice services decreased the risk of mortality for female spousal caregivers and reduced the risk of depression and complicated grief after the patient's death.

Hospice-specific caregiver interventions showed significant promise. These brief structured interventions promoted problem solving and/or meaning-based coping strategies and were found to improve caregivers' quality of life, decrease burden, and enhance positive aspects of caregiving. The psychosocial interventions were offered upon admission to a hospice program and successfully delivered in-person or via videophone.

Limitations

The studies included in this review were diverse in terms of design, assessed outcomes, and sample sizes. The absence of control groups and underutilization of repeated measures or time-series designs over the course of the dying and bereavement process limited the findings of many studies. The vast majority of participants were Caucasian females caring for a person dying of cancer, which may also be problematic for overall generalizability. Finally, there was an overreliance on self-reporting and study-specific measures to assess outcomes.

Conclusions

This study highlights the invaluable role played by informal hospice caregivers and calls for systematic research on how to maximize the positive aspects of caregiving. With advances in policy, research, and resource allocation, hospices will be better able to support the critical needs of caregivers for the dying, whose vital role enables high-quality end-of-life care for so many.

Future directions

This review was helpful in synthesizing the current literature on informal caregiving in hospice; however, future research is warranted. For example, few studies adequately addressed the impact of disease trajectories on caregivers during the period of actively providing care and during the bereavement process. Future research could consider the impact different disease trajectories have on caregivers and their well-being, and how providing support to caregivers earlier in the course of their loved one's terminal illness could be beneficial. Unfortunately, the disparities apparent in the broader health care system are found in hospice care; most U.S. hospice patients are female (56%), over the age of 65 (84%), of non-Hispanic origin (93%), and Caucasian (82%).78 Additional research is needed to better understand how to effectively support diverse caregivers not typically represented here, and to identify their specific needs once services are received.

Further research is needed to assess brief interventions that promote effective coping and enhance the positive aspects of caregiving, while also identifying factors that alleviate the detrimental aspects of caregiving. Since caregivers' cognitive appraisals of burden and stress as well as their ability to find meaning in the caring experience were predictive of enhanced well-being, future studies could more directly target and modify these subjective appraisals. Finally, as social support was associated with increased well-being and reduced burden, developing interventions that help caregivers identify and better use their informal social support networks could be beneficial.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S: Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:213–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert RS, Schulz R: Caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1174–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talley RC, Crews JE: Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health 2007;97:224–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding R, Higginson IJ: What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer and palliative care? A systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med 2003;17:63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee Y, Degenholtz HB, Lo Sasso AT, Emanuel LL: Estimating the quantity and economic value of family caregiving for community-dwelling older persons in the last year of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1654–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolff JL, Dy SM, Frick KD, Kasper JD: End-of-life care: Findings from a national survey of informal caregivers. JAMA Intern Med 2007;167:40–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grande G, Stajduhar K, Aoun S, et al. : Supporting lay carers in end of life care: Current gaps and future priorities. Palliat Med 2009;23:339–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, et al. : Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004;31:1105–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Demiris G, Parker OD, Washington K, Burt S, Shaunfield S: Stress variances among informal hospice caregivers. Qual Health Res 2012;22:1114–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bialon LN, Coke S: A study on caregiver burden: Stressors, challenges, and possible solutions. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:210–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldrop DP, Meeker MA: Crisis in caregiving: When home-based end-of-life care is no longer possible. J Palliat Care 2011;27:117–125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zivin K, Christakis NA: The emotional toll of spousal morbidity and mortality. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, Triemstra M, Spruijt RJ, Van den Bos GAM: Cancer and caregiving: The impact on the caregiver's health. Psycho-Oncology 1998;7:3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinquart M, Sorensen S: Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: A meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007;62:126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz R, Beach SR: Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The caregiver health effects study. JAMA 1999;282:2215–2219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christakis NA, Allison PD: Mortality after the hospitalization of a spouse. N Engl J Med 2006;354:719–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fredman L, Cauley JA, Satterfield S, et al. : Caregiving, mortality, and mobility decline: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) study. JAMA Intern Med 2008;168:2154–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Argimon JM, Limon E, Vila J, Cabezas C: Health-related quality-of-life of care-givers as a predictor of nursing-home placement of patients with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2005;19:41–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lotus Shyu YI, Chen MC, Lee HC: Caregiver's needs as predictors of hospital readmission for the elderly in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:1395–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC: Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull 2008;134:1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zisook S, Irwin SA, Shear K: Understanding and managing adult bereavement in palliative care. In: Chochinov HM, Breitbart W. (eds): Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine, 2nd ed New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 202–219 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J: Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(S1):6–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. : Guidance on the conducting of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Lancaster, UK: ESRC Methods Programme, Institute for Health Research, Lancaster University [Google Scholar]

- 24.Archer KC, Boyle DP: Toward a measure of caregiver satisfaction with hospice social services. Hospice J 1999;14:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganzini L, Johnston WS, Silveira MJ: The final month of life in patients with ALS. JAMA Neurol 2002;59:428–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein NE, Concato J, Fried TR, Kasl SV, Hurzeler RJ, Bradley EH: Factors associated with caregiver burden among caregivers of terminally ill patients with cancer. J Palliat Care 2004;20:38–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goy ER, Carter JH, Ganzini L: Needs and experiences of caregivers for family members dying with Parkinson disease. J Palliat Care 2008;24:69–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holtslander LF, McMillan SC: Depressive symptoms, grief, and complicated grief among family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer three months into bereavement. Oncol Nurs Forum 2011;38:60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang WR: Hospice family caregivers' quality of life. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:2563–2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernard LL, Guarnaccia CA: Two models of caregiver strain and bereavement adjustment: A comparison of husband and daughter caregivers of breast cancer hospice patients. Gerontologist 2003;43:808–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demiris G, Oliver DP, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K: Use of videophones to deliver a cognitive-behavioural therapy to hospice caregivers. J Telemed Telecare 2011;17:142–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chentsova-Dutton Y, Shuchter S, Hutchin S, Strause L, Burns K, Zisook S: The psychological and physical health of hospice caregivers. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2000;12:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demiris G, Oliver DP, Washington K, et al. : A problem solving intervention for hospice caregivers: A pilot study. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1005–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haley WE, LaMonde LA, Han B, Burton AM, Schonwetter R: Predictors of depression and life satisfaction among spousal caregivers in hospice: Application of a stress process model. J Palliat Med 2003;6:215–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilder HM, Oliver DP, Demiris G, Washington K: Informal hospice caregiving: The toll on quality of life. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2008;4:312–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salmon JR, Kwak J, Acquaviva KD, Brandt K, Egan KA: Transformative aspects of caregiving at life's end. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29:121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cagle JG, Kovacs PJ: Informal caregivers of cancer patients: Perceptions about preparedness and support during hospice care. J Gerontol Soc Work 2011;54:92–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herth K: Hope in the family caregiver of terminally ill people. J Adv Nurs 1993;18:538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreling B, Selsky C, Perret-Gentil M, Huerta EE, Mandelblatt JS; Latin American Cancer Research Coalition: 'The worst thing about hospice is that they talk about death': Contrasting hospice decisions and experience among immigrant Central and South American Latinos with US-born white, non-Latino cancer caregivers. Palliat Med 2010;24:427–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al. : Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer 2006;106:214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demiris G, Parker OD, Wittenberg-Lyles E, et al. : A noninferiority trial of a problem-solving intervention for hospice caregivers: In person versus videophone. J Palliat Med 2012;15:653–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMillan SC, Small BJ, Haley WE: Improving hospice outcomes through systematic assessment: A clinical trial. Cancer Nurs 2011;34:89–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernard LL, Guarnaccia CA: Husband and adult-daughter caregivers' bereavement. Omega (Westport) 2002;45:153–166 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ: The health impact of health care on families: A matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weitzner MA, McMillan SC, Jacobsen PB: Family caregiver quality of life: Differences between curative and palliative cancer treatment settings. J Pain Symptom Manage 1999;17:418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McMillan SC: Quality of life of primary caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer Pract 1996;4:191–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. : Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chentsova-Dutton Y, Shucter S, Hutchin S, et al. : Depression and grief reactions in hospice caregivers: From pre-death to 1 year afterwards. J Affect Disord 2002;69:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kris AE, Cherlin EJ, Prigerson H, et al. : Length of hospice enrollment and subsequent depression in family caregivers: 13-month follow-up study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:264–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.York GS, Churchman R, Woodard B, Wainright C, Rau-Foster M: Free-text comments: Understanding the value in family member descriptions of hospice caregiver relationships. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:98–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casarett DJ, Hirschman KB, Crowley R, Galbraith LD, Leo M: Caregivers' satisfaction with hospice care in the last 24 hours of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2003;20:205–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyers JL, Gray LN: The relationships between family primary caregiver characteristics and satisfaction with hospice care, quality of life, and burden. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001;28:73–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dawson NJ: Need satisfaction in terminal care settings. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:83–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evans WG, Cutson TM, Steinhauser KE, Tulsky JA: Is there no place like home? Caregivers recall reasons for and experience upon transfer from home hospice to inpatient facilities. J Palliat Med 2006;9:100–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steele LL, Mills B, Long MR, Hagopian GA: Patient and caregiver satisfaction with end-of-life care: Does high satisfaction mean high quality of care? Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2002;19:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haley WE, LaMonde LA, Han B, Narramore S, Schonwetter R: Family caregiving in hospice: Effects on psychological and health functioning among spousal caregivers of hospice patients with lung cancer or dementia. Hospice J 2001;15:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prigerson HG, Cherlin E, Chen JH, Kasl SV, Hurzeler R, Bradley EH: The stressful caregiving adult reactions to experiences of dying (SCARED) scale: A measure for assessing caregiver exposure to distress in terminal care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11:309–319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gill P, Kaur JS, Rummans T, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA: The hospice patient's primary caregiver: What is their quality of life? J Psychosom Res 2003;55:445–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Demiris G, Oliver DP, Burt S: Reciprocal suffering: Caregiver concerns during hospice care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:383–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kutner J, Kilbourn KM, Costenaro A, et al. : Support needs of informal hospice caregivers: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2009;12:1101–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Newton M, Bell D, Lambert S, Fearing A: Concerns of hospice patient caregivers. ABNF J 2002;13:140–144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Townsend AL, Ishler KJ, Shapiro BM, Pitorak EF, Matthews CR: Levels, types, and predictors of family caregiver strain during hospice home care for an older adult. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2010;6:51–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones BW: Hospice disease types which indicate a greater need for bereavement counseling. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2010;27:187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moody LE, McMillan S: Dyspnea and quality of life indicators in hospice patients and their caregivers. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McMillan SC, Mahon M: The impact of hospice services on the quality of life of primary caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum 1994;21:1189–1195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Speer DC, Robinson BE, Reed MP: The relationship between hospice length of stay and caregiver adjustment. Hospice J 1995;10:45–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fenix JB, Cherlin EJ, Prigerson HG, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Kasl SV, Bradley EH: Religiousness and major depression among bereaved family caregivers: A 13-month follow-up study. J Palliat Care 2006;22:286–292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mickley JR, Pargament KI, Brant CR, Hipp KM: God and the search for meaning among hospice caregivers. Hospice J 1998;13:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Drach LL, Perrin NA: Out-of-hospital death: Advance care planning, decedent symptoms, and caregiver burden. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:532–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kramer BJ, Kavanaugh M, Trentham-Dietz A, Walsh M, Yonker JA: Complicated grief symptoms in caregivers of persons with lung cancer: The role of family conflict, intrapsychic strains, and hospice utilization. Omega (Westport) 2010;62:201–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG: Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4457–4464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kilbourn KM, Costenaro A, Madore S, et al. : Feasibility of a telephone-based counseling program for informal caregivers of hospice patients. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1200–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Demiris G, Oliver DP, Courtney KL, Day M: Telehospice tools for caregivers: A pilot study. Clin Gerontol 2007;31:43–57 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parker OD, Demiris G, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Porock D, Collier J, Arthur A: Caregiver participation in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings via videophone technology: A pilot study to improve pain management. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2010;27:465–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kwak J, Salmon JR, Acquaviva KD, Brandt K, Egan KA: Benefits of training family caregivers on experiences of closure during end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:434–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Empeno J, Raming NT, Irwin SA, Nelesen RA, Lloyd LS: The hospice caregiver support project: Providing support to reduce caregiver stress. J Palliat Med 2011;14:593–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America, 2013. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hull MM: Sources of stress for hospice caregiving families. Hospice J 1990;6:29–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Redinbaugh EM, Baum A, Tarbell S, Arnold R: End-of-life caregiving: What helps family caregivers cope? J Palliat Med 2003;6:901–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]