Abstract

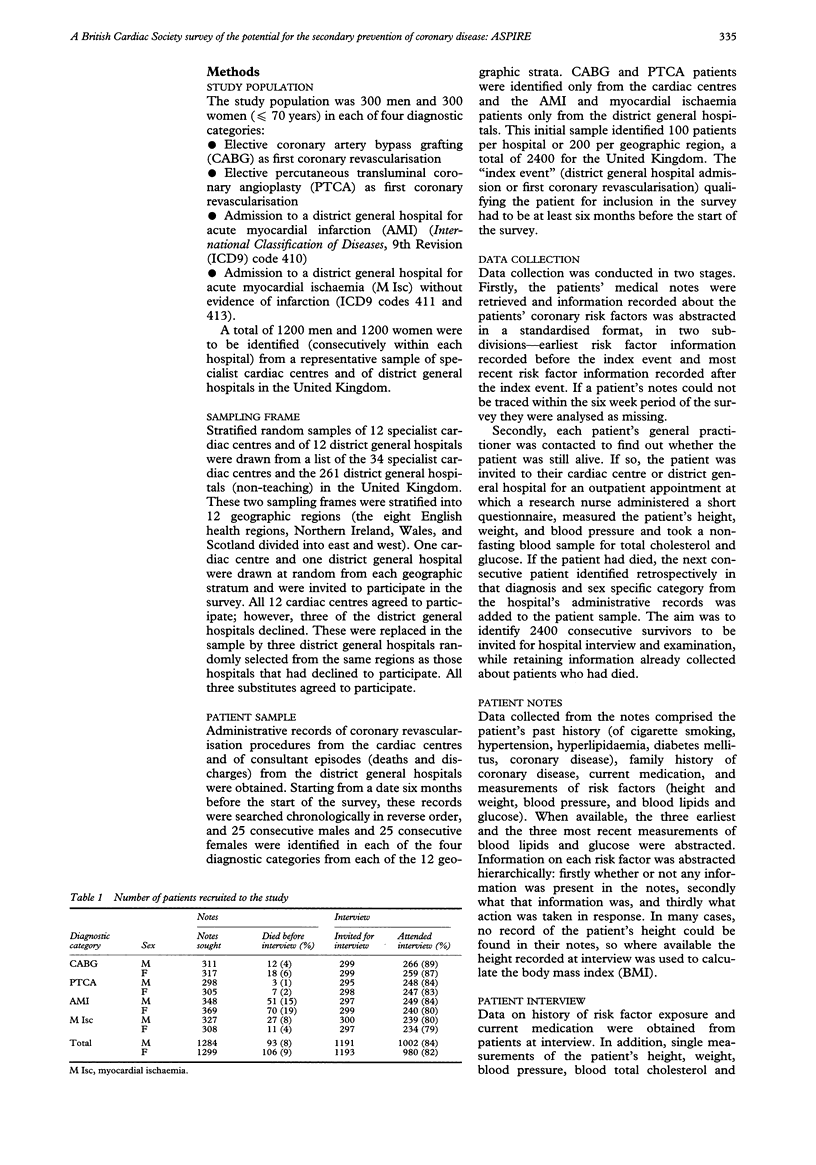

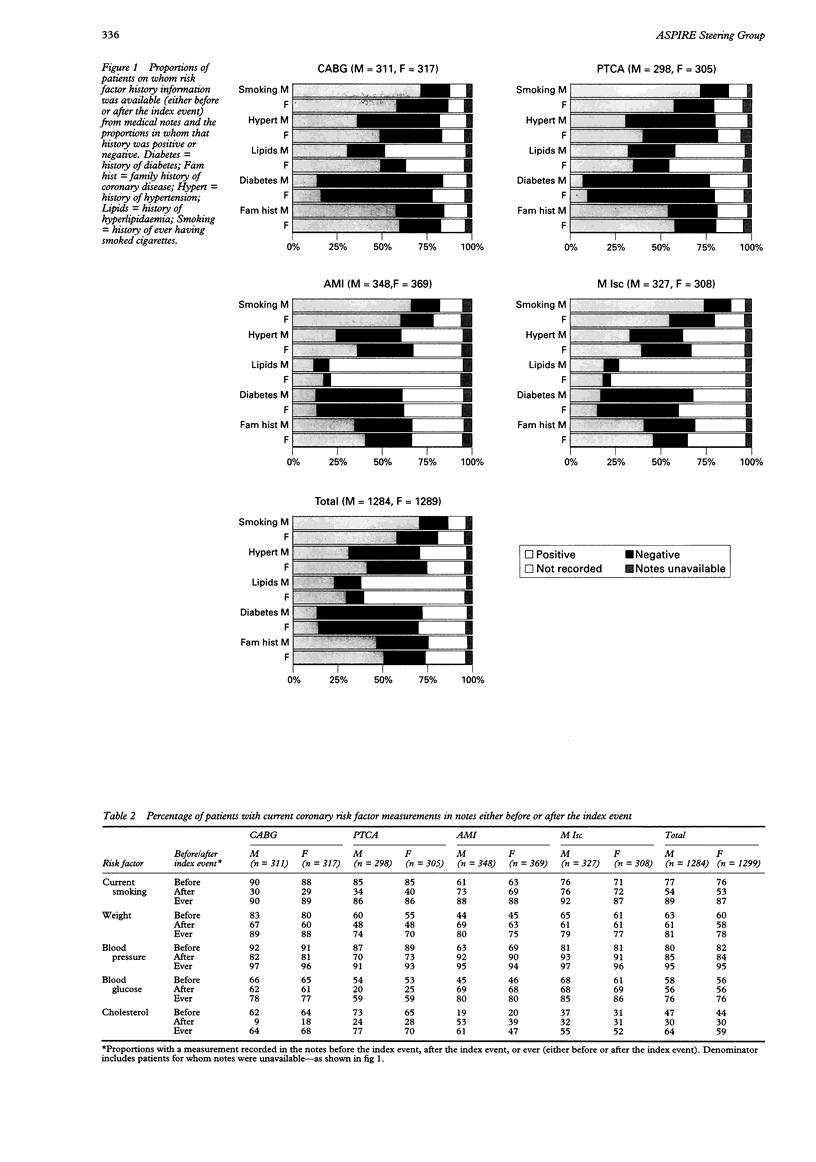

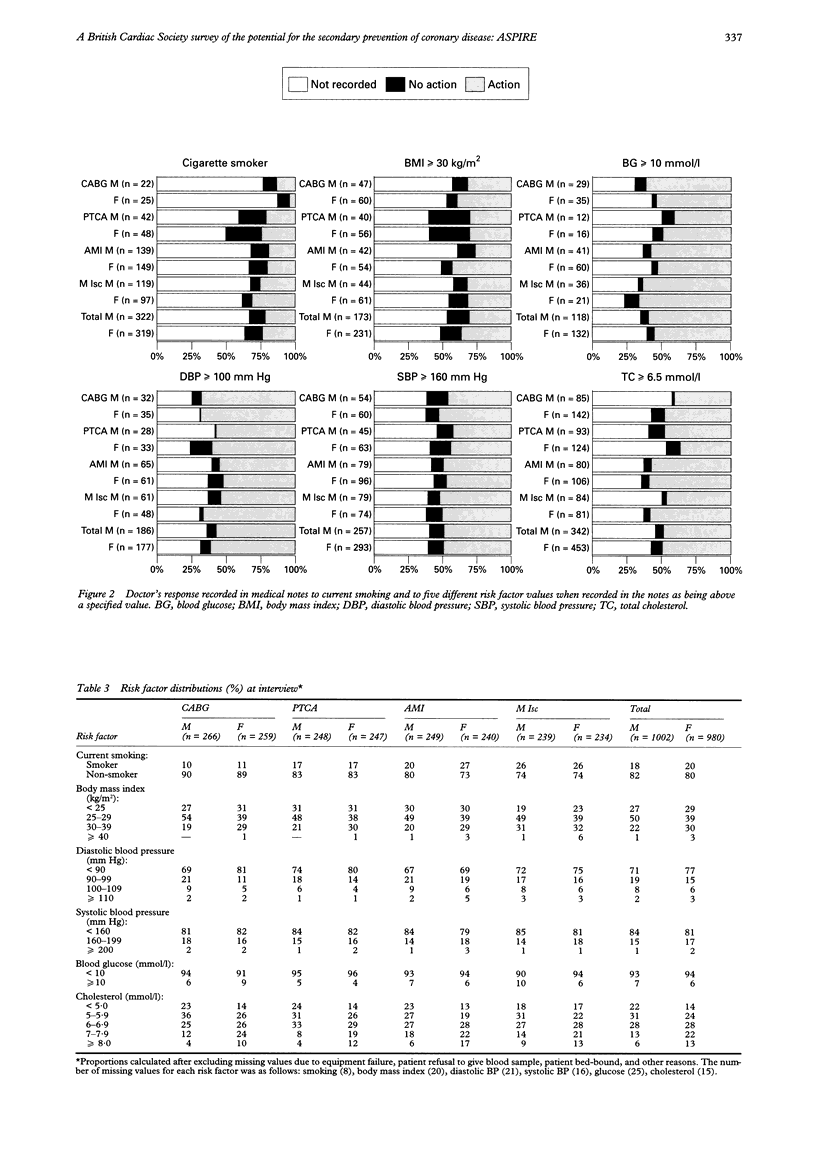

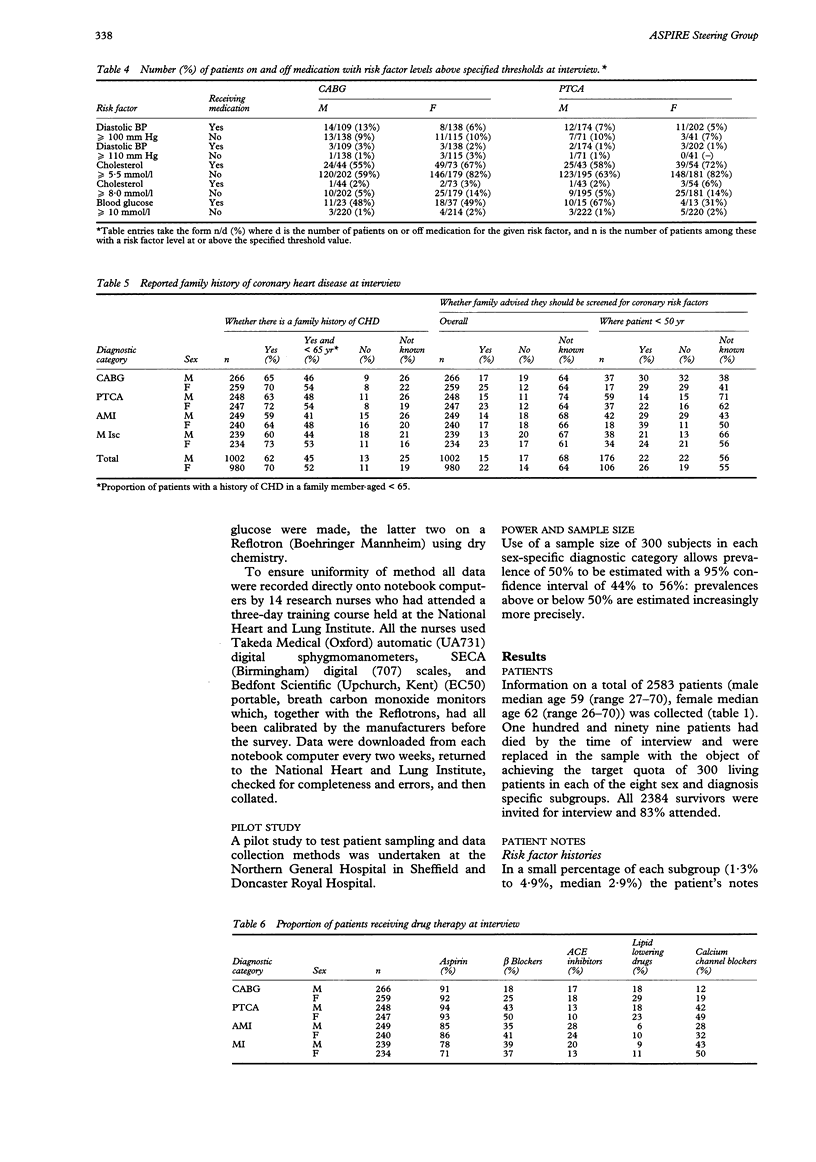

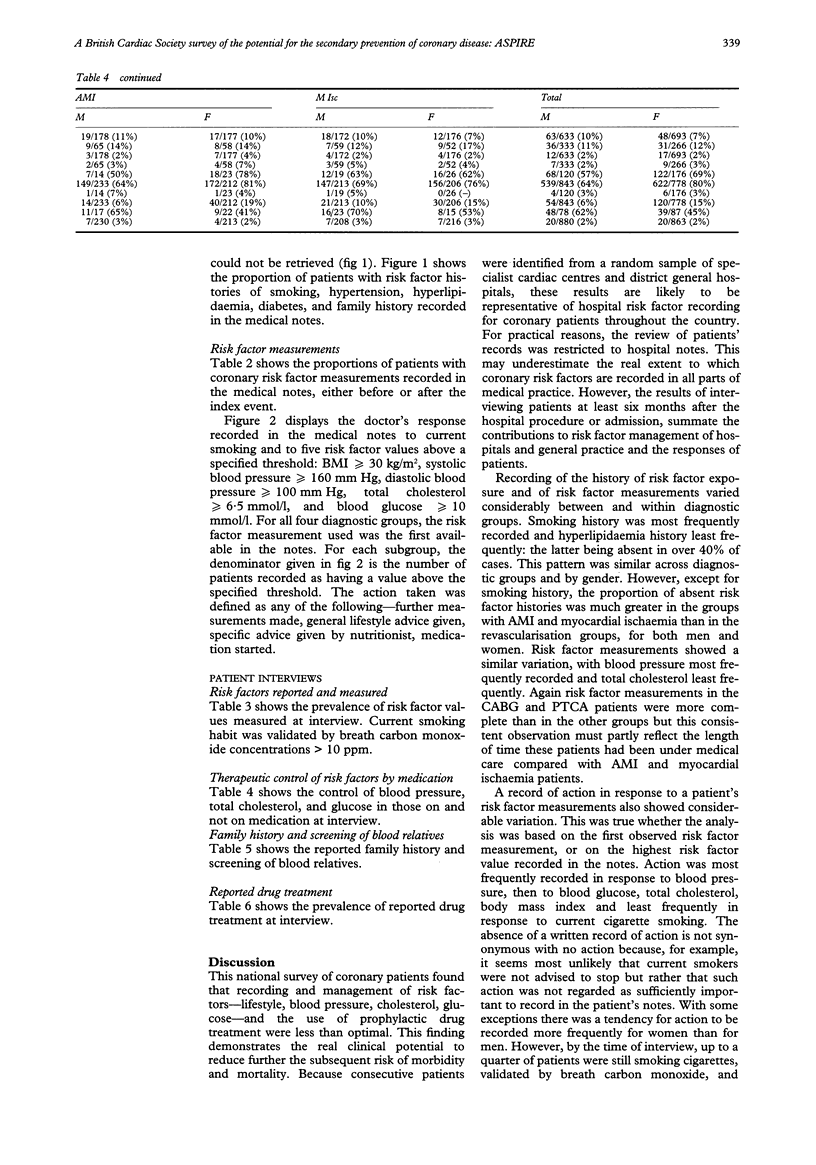

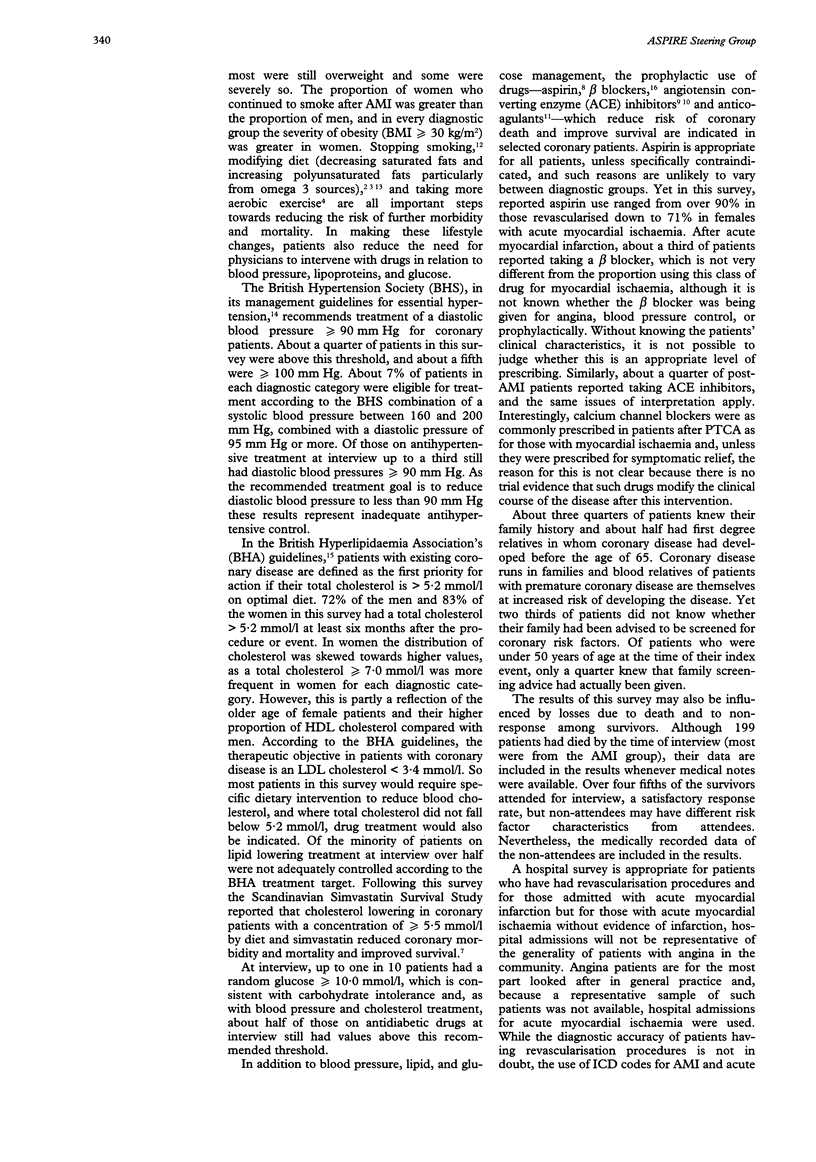

OBJECTIVE: To measure the potential for secondary prevention of coronary disease in the United Kingdom. DESIGN: Cross sectional survey of a representative sample of coronary patients from a retrospective review of hospital medical records and patient interview and examination. SETTING: Stratified random sample of 12 specialist cardiac centres and 12 district general hospitals drawn from 34 specialist cardiac centres and 261 district general hospitals in 12 geographic areas in the United Kingdom. SUBJECTS: 2583 patients < or = 70 yr; 25 consecutive males and 25 consecutive females identified retrospectively in each of four diagnostic categories: coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, acute myocardial infarction, and acute myocardial ischaemia without evidence of infarction. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Risk factor recording and management in medical records; the prevalence and control of risk factors at interview six months after the procedure or event. RESULTS: Recording of coronary risk factors in patient's records was incomplete and this varied by risk factor. Smoking habit and blood pressure were most completely recorded, whereas a history of hyperlipidaemia and blood cholesterol concentrations were least complete. Risk factor records were more likely to be complete in cardiac centres than in district hospitals. At interview 10% to 27% of patients were still smoking cigarettes and 75% remained overweight, females more severely so. Up to a quarter of patients remained hypertensive, males more severely so than females. Over three quarters had a total cholesterol > 5.2 mmol/l. In patients on medication for blood pressure, cholesterol or glucose, risk factor profiles were little better than in those who were not. Only about one patient in three was taking a beta blocker after infarction. Up to a fifth of patients who had had acute myocardial ischaemia were not taking aspirin at follow up. CONCLUSIONS: There is considerable potential to reduce the risk of a further major ischaemic event in patients with established coronary disease. This can be achieved by effective lifestyle intervention, the rigorous management of blood pressure and cholesterol, and the appropriate use of prophylactic drugs.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aberg A., Bergstrand R., Johansson S., Ulvenstam G., Vedin A., Wedel H., Wilhelmsson C., Wilhelmsen L. Cessation of smoking after myocardial infarction. Effects on mortality after 10 years. Br Heart J. 1983 May;49(5):416–422. doi: 10.1136/hrt.49.5.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betteridge D. J., Dodson P. M., Durrington P. N., Hughes E. A., Laker M. F., Nicholls D. P., Rees J. A., Seymour C. A., Thompson G. R., Winder A. F. Management of hyperlipidaemia: guidelines of the British Hyperlipidaemia Association. Postgrad Med J. 1993 May;69(811):359–369. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.69.811.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr M. L., Fehily A. M., Gilbert J. F., Rogers S., Holliday R. M., Sweetnam P. M., Elwood P. C., Deadman N. M. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART). Lancet. 1989 Sep 30;2(8666):757–761. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R., Peto R., MacMahon S., Hebert P., Fiebach N. H., Eberlein K. A., Godwin J., Qizilbash N., Taylor J. O., Hennekens C. H. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990 Apr 7;335(8693):827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M. R., Wald N. J., Thompson S. G. By how much and how quickly does reduction in serum cholesterol concentration lower risk of ischaemic heart disease? BMJ. 1994 Feb 5;308(6925):367–372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor G. T., Buring J. E., Yusuf S., Goldhaber S. Z., Olmstead E. M., Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Hennekens C. H. An overview of randomized trials of rehabilitation with exercise after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1989 Aug;80(2):234–244. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer M. A., Braunwald E., Moyé L. A., Basta L., Brown E. J., Jr, Cuddy T. E., Davis B. R., Geltman E. M., Goldman S., Flaker G. C. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992 Sep 3;327(10):669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyörälä K., De Backer G., Graham I., Poole-Wilson P., Wood D. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, European Atherosclerosis Society and European Society of Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 1994 Oct;15(10):1300–1331. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sever P., Beevers G., Bulpitt C., Lever A., Ramsay L., Reid J., Swales J. Management guidelines in essential hypertension: report of the second working party of the British Hypertension Society. BMJ. 1993 Apr 10;306(6883):983–987. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6883.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P., Arnesen H., Holme I. The effect of warfarin on mortality and reinfarction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jul 19;323(3):147–152. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007193230302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lorgeril M., Renaud S., Mamelle N., Salen P., Martin J. L., Monjaud I., Guidollet J., Touboul P., Delaye J. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1994 Jun 11;343(8911):1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]