Abstract

Objective

Current recommendations advocate treatment with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in all patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We investigated the frequency of and reasons for inconsistent DMARD use among patients in a clinical rheumatology cohort.

Methods

Patients in the Brigham Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study were studied for DMARD use (any or none) at each semi-annual study time point during the first two study years. Inconsistent use was defined as DMARD use at ≤40 % of study time points. Characteristics were compared between inconsistent and consistent users (>40%), and factors associated with inconsistent DMARD use were determined through multivariate logistic regression. A medical record review was performed to determine the reasons for inconsistent use.

Results

Of 848 patients with ≥4 out of 5 visits recorded, 55 (6.5%) were inconsistent DMARD users. Higher age, longer disease duration and rheumatoid factor negativity were statistically significant correlates of inconsistent use in the multivariate analyses. The primary reasons for inconsistent use identified through chart review, allowing for up to 2 co-primary reasons, were inactive disease (n=28, 50.9%), intolerance to DMARDs (n=18, 32.7%), patient preference (n=7, 12.7%), comorbidity (n=6, 10.9%), DMARDs not being effective (n=3, 5.5%), and pregnancy (n=3, 5.5%). During subsequent follow-up, 14/45 (31.1%) of inconsistent users with sufficient data became consistent users of DMARDs.

Conclusion

A small proportion of RA patients in a clinical rheumatology cohort were inconsistent DMARD users during the first two years of follow up. While various patient factors correlate with inconsistent use, many patients re-start DMARDs and become consistent users over time.

Key Indexing Terms: Rheumatoid arthritis, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, longitudinal studies, drug adherence

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have been shown to effectively reduce the signs and symptoms of RA and to improve long-term outcomes.(1, 2) Accordingly, current American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations support the use of DMARDs in all patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA).(3, 4) As a result of the focus on timely intervention with DMARDs and close monitoring of disease activity with a structured, treat-to-target approach in recent years, patients seen by rheumatologists are more likely to receive DMARDs than patients seen by unselected physicians.(5) However, results from contemporary RA cohorts show that even in specialized rheumatology clinics, a proportion of patients are not treated with DMARDs.(6–12).

Previous studies investigating DMARD use have mainly performed cross-sectional analyses, and are thus unable to characterize consistency of use over time and changes in DMARD use patterns. To our knowledge, no detailed reports have been published that analyzed the consistency of DMARD use in longitudinal data. Understanding the extent of inconsistent use and examining the reasons why some RA patients do not use DMARDs over a longer period of time could aid clinical treatment decisions and help tailor quality improvement interventions at the patient level.

The aims of this study were 1) to describe the consistency of DMARD use during the first two years after inclusion in an observational RA cohort, 2) to identify factors associated with inconsistent versus consistent DMARD use, and 3) to determine the reasons for inconsistent DMARD use according to the medical record.

Patients and methods

Study cohort

The Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study (BRASS) is an observational single-center cohort consisting of more than 1,300 patients that have been diagnosed with RA by board-certified rheumatologists.(13). Ninety-six percent of BRASS patients fulfilled the 1987 ACR classification criteria for RA at inclusion.(14, 15) Patients were assessed annually with a comprehensive investigation including clinical and laboratory measures, and semi-annually with patient reported outcome measures. There was no pre-defined treatment protocol in BRASS. Thirty-eight rheumatologists participated in the data collection and provided patient care, with 10 (26 %) being full-time clinicians. Patients included in the present analyses were recruited between 2003 and 2010 and had at least four study time points recorded within the first two years of follow-up. Of 848 patients, 670 (79 %) were included in 2003 and 2004. The study was approved by The Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board and all patients gave written consent.

Assessment of DMARD use

The following agents were considered as DMARDs in these analyses: methotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, azathioprine, penicillamine, cyclophosphamide, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, auranofin injectable gold salts, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab, anakinra, adalimumab, rituximab, abatacept, tocilizumab. Patients were categorized as consistent DMARD users if they reported using any DMARD on three or more out of a possible maximum of five study time points during the first two years of follow-up (>40% of time points). Persistence on the same DMARD was not required as DMARDs were treated as a drug class. Patients using DMARDs on two or fewer time points during the first two years of follow-up were categorized as inconsistent users. Patients were assumed to be treated with DMARDs on missing study time points to prevent underestimation of use. Missing time points constituted 5.4% of the total number of study time points.

Medical record review

The electronic medical records (EMR) of patients identified as inconsistent users from the study data were reviewed in a structured way by one of the authors (MDM), using a data extraction sheet created for this purpose (see Supplementary Table S1). The treating rheumatologist’s notes were reviewed for data on previous and current DMARD use (number and type), and the reasons for not using DMARDs were recorded and categorized as well as graded by relevance as the primary reason, secondary reason, or tertiary reason. Intolerance to treatment was recorded when side effects or adverse events was mentioned as the reason for inconsistent DMARD use. We also determined if any of the inconsistent users became consistent DMARD users subsequent to the first two study years. For this analysis, we used all available data in the EMR for patients with ≥24 months of EMR follow-up subsequent to the first two years after enrollment in BRASS. No minimum number of EMR entries within this follow-up was required. Patients were defined as subsequent consistent DMARD users if they were found to use DMARDs continuously for 24 months or more during subsequent follow-up and were still using DMARDs at the last recorded EMR entry.

Statistical analysis

Continuous measures were reported as means and standard deviations or medians and 25th to 75th percentiles according to the distribution of the data. Categorical data were reported as numbers and proportions. For the proportions reported from the EMR review, confidence intervals were calculated according to the method described by Clopper and Pearson.(16) Comparisons between inconsistent and consistent DMARD users were performed with Student’s T tests, Mann-Whitney U tests or Chi-Square tests as appropriate. The following variables were assessed: age, sex, disease duration, rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody positivity, current smoking, comorbidity measured by the Charlson index (17) (a modified version of the Charlson index that does not include information on all comorbidities was used), marital status, employment status, level of education, ethnicity (Caucasian yes/no), prednisone use at baseline and during follow-up, C-reactive protein (CRP), number of swollen and tender joints, patient’s assessment of global disease activity measured by the Multi-Dimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ)(18), physician’s assessment of global disease activity, Disease Activity Score-28 calculated with CRP, pain and fatigue measured by the MDHAQ, and functional status measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire.(19) Factors independently associated with inconsistent DMARD use were determined by logistic regression analyses. Variables with p values <0.25 in univariate analyses were included in multivariate logistic regression analyses with inconsistent DMARD use as the dependent variable. All models were controlled for age and gender. First, the most parsimonious primary model was determined by backward manual selection. Second, alternative models were explored by introducing clinically meaningful variables into the primary model. The discriminative abilities of the models were assessed by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) of the predicted probabilities of each model. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 and R version 3.0.2/pROC package version 1.5.4.(20)

Results

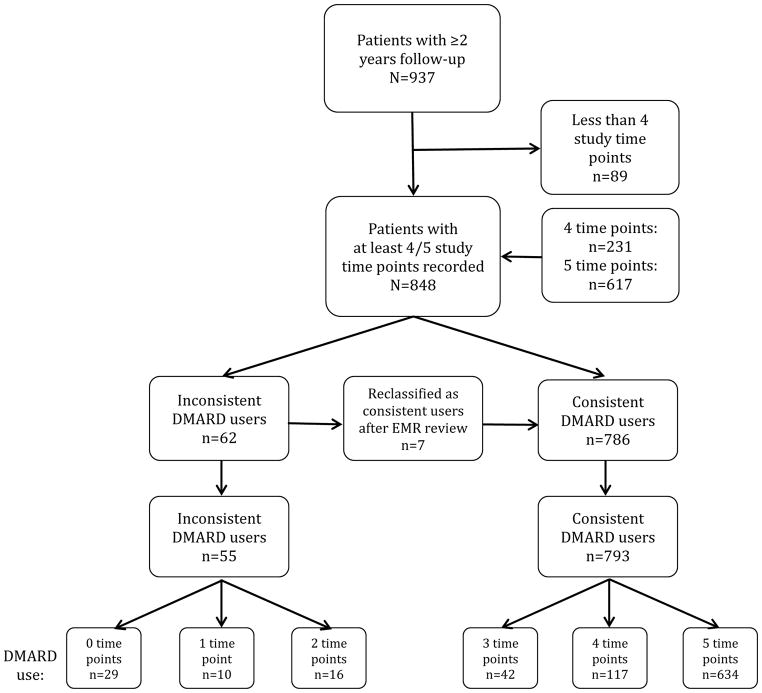

The patient selection and distribution of DMARD use is illustrated in Figure 1. Of the 937 patients that had two years of follow-up, 848 had four (n=231) or five (n=617) study time points for the first two years recorded. Sixty-two patients were identified as inconsistent DMARD users in the BRASS data file, but seven of these were reclassified as consistent users after the EMR review, leaving 55 inconsistent users (6.5%) for further study. Of these, 29 (52.7 %) did not use a DMARD on any study time points during the first two years of follow-up, 10 used a DMARD on one time point, and 16 patients used a DMARD on two time points. The majority (94.7%) of the 793 consistent DMARD users reported DMARD use on four or five time points (n=751). Among the 26 inconsistent users who did use one or more DMARDs on ≤2 study time points during the 2-year study period, the most frequently used drug was methotrexate (n=12), followed by hydroxychloroquine (n=6), leflunomide (n=5) and sulfasalazine (n=3) (see Supplementary Table S1). Five patients used a biologic DMARD. Other agents used by inconsistent users were gold, penicillamine and cyclosporine (n=3). In these 26 patients more than one drug could be used simultaneously or at different time points by the same patient.

Figure 1.

Overview of patient selection and DMARD use. DMARD; disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug.

Factors associated with inconsistent DMARD use

Inconsistent DMARD users were older (mean age 60.6 years vs. 56.3 years, p=0.02) and were less frequently rheumatoid factor (RF) (33.3 vs. 67.1%, p<0.0001) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) positive (40.0 vs. 65.8%, p<0.001) than consistent users in the univariate analyses (Table 1). Inconsistent users also had a lower rate of employment (37.7 vs. 52.6%, p=0.04). There was a trend towards longer disease duration and higher Charlson index in the inconsistent user group, but the differences were not statistically significant. Pain, fatigue, functional status and disease activity were similar in the two groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics in inconsistent and consistent DMARD users in the BRASS cohort.

| Variable$ | Missing values | Inconsistent users N=55 |

Consistent users N=793 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 0 | 60.6 (14.5) | 56.3 (13.0) | 0.02* |

| Females, n (%) | 0 | 45 (81.8) | 663 (83.6) | 0.73 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis duration (years), mean (SD) | 0 | 16.5 (13.9) | 13.6 (11.8) | 0.08* |

| Rheumatoid factor positive, n (%) | 19 | 18/54 (33.3) | 520/775 (67.1) | <0.0001* |

| Anti-CCP positive, n (%) | 0 | 22 (40.0) | 522 (65.8) | <0.001* |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 41 | 5/54 (9.3) | 55/753 (7.3) | 0.60 |

| Charlson index, median (25th–75th percentile) | 0 | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 0.10* |

| Married, n (%) | 2 | 37 (67.3) | 520/791 (65.7) | 0.82 |

| Employed, n (%) | 38 | 20/53 (37.7) | 398/757(52.6) | 0.04* |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | 5 | 0.16* | ||

| -Did not graduate from high school | 1 (1.8) | 24 (3.0) | ||

| -Graduated high school but not college | 30 (54.5) | 327 (41.5) | ||

| -Graduated college | 24 (43.6) | 437 (55.5) | ||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 8 | 49 (89.1) | 740/785 (94.3) | 0.12* |

| Prednisone use at inclusion, n (%) | 0 | 19 (34.5) | 295 (37.2) | 0.69 |

| Prednisone use any time during the 2-year follow-up, n (%) | 0 | 295 (37.2) | 19 (34.5) | 0.70 |

| CRP (mg/L), median (25th–75th percentile) | 7 | 4.04 (1.11–12.81) | 2.87 (1.05–7.87) | 0.29 |

| No. of swollen joints (0–28), mean (SD) | 0 | 7.1 (8.2) | 7.4 (7.2) | 0.75 |

| No. of tender joints (0–28), mean (SD) | 0 | 9.2 (8.9) | 8.1 (7.8) | 0.32 |

| MDHAQ patient global scale§, mean (SD) | 40 | 25.9 (24.3) | 31.0 (24.7) | 0.15* |

| Physician global disease activity£, mean (SD) | 12 | 34.4 (27.4) | 32.8 (21.2) | 0.61 |

| DAS28-CRP(4), mean (SD) | 47 | 3.96 (1.65) | 3.89 (1.60) | 0.78 |

| DAS28-CRP(4) AUC, mean (SD) | 1 | 3.67 (1.59) | 3.48 (1.39) | 0.33 |

| MDHAQ pain scale§, mean (SD) | 65 | 37.1 (31.1) | 34.7 (26.8) | 0.54 |

| MDHAQ fatigue scale§, mean (SD) | 40 | 38.2(28.4) | 41.3 (28.7) | 0.43 |

| MHAQ score, median (25th–75th percentile) | 40 | 0.20 (0.00–0.65) | 0.30 (0.00–0.60) | 0.86 |

(SD) are presented for normally distributed variables, and medians (25th –75th percentiles) are presented for non-normally distributed variables.

At study inclusion unless stated otherwise

p<0.25, variable included in multivariate analyses (Table 2).

Recorded from 0–100 in increments of 5, with higher values corresponding to a worse state.

Recorded from 0–100 in integers of 10, with higher values corresponding to a worse state.

DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; SD, standard deviation; CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; CRP, C-reactive protein; mg/L, milligrams per liter; MDHAQ, Multi-Dimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire; DAS28-CRP(4), Disease Activity Score 28-CRP with 4 variables; AUC, area under the curve over two years follow-up, MHAQ, Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire.

The results of the multivariate logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 2. The primary model showed that higher age, longer disease duration, and RF negativity were associated with inconsistent DMARD use. We explored several alternative models, including models with the individual components of the Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS28), the baseline and the time-averaged DAS28 (calculated as in Bøyesen et al (21), for method description see Supplementary file) over the first two years of follow-up, concurrent prednisone use and comorbidity measured by a modified version of the Charlson index.(22) The results of three alternative models are shown in Table 2. To summarize, the AUC did not improve in any of the alternative models, compared to the primary model.

Table 2.

Logistic regression models with inconsistent DMARD use as dependent variable.

| Univariate analysis | Primary model | Secondary models | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + Baseline DAS28 | + Time-averaged DAS28 | + Charlson index | |||

| OR (95 % CI) | OR (95 % CI) | OR (95 % CI) | OR (95 % CI) | OR (95 % CI) | |

| Age, per year | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) |

| Female gender | 0.88 (0.43–1.80) | 1.12 (0.53–2.35) | 0.93 (0.44–1.97) | 1.09 (0.52–2.29) | 1.11 (0.53–2.34) |

| RA duration, per year | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) |

| RF + | 0.25 (0.14–0.44) | 0.20 (0.11–0.36) | 0.23 (0.12–0.42) | 0.19 (0.10–0.35) | 0.20 (0.11–0.36) |

| Baseline DAS28 | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | - | 1.01 (0.83–1.23) | - | - |

| Time-averaged DAS28 | 1.10 (0.91–1.33) | - | - | 1.12 (0.90–1.39) | - |

| Charlson index | 1.20 (0.99–1.44) | - | - | - | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) |

| AUC (95 % CI) | 0.74 (0.67–0.81) | 0.73 (0.65–0.80) | 0.74 (0.67–0.81) | 0.74 (0.67–0.81) | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BL, baseline; DAS28, Disease Activity Score 28; time-averaged, area under the curve over two years; AUC, area under the curve; RA rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Reasons for not using DMARDs according to the medical record

The reasons for inconsistent DMARD use found in the medical records could all be categorized into one of five categories (Table 3). While many patients were found to have several reasons for inconsistent DMARD use, in most patients a single primary reason for not being treated with a DMARD could be determined from the EMR review (see Supplementary Table 1 for details). The most frequent reason for not using DMARDs was that the patients were felt by their rheumatologist to have inactive disease and thus were without indication for a DMARD to be prescribed. This was supported by the clinical data, as the mean (SD) time-averaged DAS28 was lower in patients whose primary reason for inconsistent DMARD use was inactive disease (n=28) than in the other inconsistent users (3.26 (1.53) vs. 4.16 (1.55), p=0.03). The majority of the inconsistent DMARD users felt to have inactive RA by their provider had previously been treated with one or more DMARDs (Supplementary Table 1), most frequently hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, sulfasalazine and gold (detailed data not shown).

Table 3.

Reasons for inconsistent DMARD use in 55 patients in BRASS as determined from medical record review

| Primary reason | Any reason n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (95 % CI)* | n | % (95 % CI)* | |

| DMARD not indicated/inactive disease | 28 | 50.9 (37.1–64.6) | 36 | 65.5(51.4–77.8) |

| Intolerance to DMARD/adverse events | 18 | 32.7 (20.7–46.7) | 30 | 54.5(40.6–68.0) |

| Patient reluctant to take DMARD | 7 | 12.7 (5.3–24.5) | 15 | 27.3(16.1–41.0) |

| Comorbidity | 6 | 10.9(4.1–22.2) | 14 | 25.5(14.7–39.0) |

| DMARDs not effective | 3 | 5.5 (1.1–15.1) | 4 | 7.3(2.0–17.6) |

| Pregnancy | 3 | 5.5 (1.1–15.1) | 3 | 5.5 (1.1–15.1) |

The percentages add up to >100% as 10 patients were found to have two co-primary reasons.

BRASS, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study; CI, confidence interval; DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

Intolerance to the treatment was the second most common reason, followed by the patient’s choice not to take a DMARD although recommended by the rheumatologist. Other reasons were comorbidity, lack of efficiency of previously used DMARDs, as well as pregnancy or trying to conceive. In the 6 patients where comorbidities were found to be the primary reason for preventing DMARD use, the comorbid conditions were: chronic leg ulcers (n=3), lung cancer (n=1), history of near fatal meningitis on combination methotrexate and leflunomide (n=1) and myelodysplasia/pancytopenia (n=1). Ten patients were found to have more than one reason that played equal roles in influencing inconsistent use. For example, one patient was found to be in remission for the first year of the study, and when a flare occurred during the second year, the patient decided not to take the recommended drug. Insurance issues or financial problems were not mentioned as a reason for DMARD non-use in any of the 55 subjects’ medical records. For detailed results from the EMR review for each patient, see Supplementary Table S1.

Subsequent DMARD treatment

In 45 of the inconsistent users, information about DMARD treatment for at least two additional years was available in the EMR. The mean follow-up time in these patients was 81 months. Fourteen of these 45 inconsistent DMARD users (31.1%) started DMARD treatment during follow-up and remained on the treatment for at least 24 months (i.e. became consistent DMARD users).

Discussion

Consistent use of DMARDs over time is recommended for improved long-term outcomes in RA. Treatment should be tightly controlled, aimed at remission or low disease activity, and should be based on a shared decision regarding the appropriate treatment target between the patient and the rheumatologist.(3, 4) However, little is known about the consistency of DMARD use over time in clinical rheumatology practice. The present study is the first longitudinal study to analyze the pattern of DMARD treatment in individual patients. We found very few inconsistent users in this rheumatology-based RA cohort. Patient characteristics associated with inconsistent use included older age, seronegative RA, and longer RA duration. A number of clinically sensible factors could be found in the EMR as reasons for inconsistent use. Also, almost one-third of inconsistent users became consistent users over the subsequent two years.

A recent systematic literature review found that 2–23% of RA patients followed by a rheumatologist did not receive DMARDs.(5) Another review of selected clinical databases and cohorts found that 5–58% of the patients in studies reporting data from the 2000s were not treated with DMARDs.(23) It is interesting that the rate of DMARD use over time in BRASS was fairly high compared to the findings in the cross-sectional studies presented in these reviews. This could reflect that some patients in cross-sectional analyses are misclassified as non-users when DMARD use is only studied at one time point. The different rates of DMARD use could also be explained by differences in study demographics, availability of DMARDs and cultural factors.

Inconsistent use was associated with older age, even after controlling for comorbidity and disease activity. DeWitt et al studied predictors of initiation of biologics in 1,545 RA patients in the ARAMIS data bank, and found that higher age was a significantly associated with decreased use of biologics.(10) They also found that higher income, higher disability and previous steroid use were associated with starting biologics. Relative under-use of DMARDs in older patients has also been found in claims-based and observational studies.(24, 25) A mail survey performed among 204 US rheumatologists asked for their treatment recommendations for two case scenarios that only differed with regard to age.(26) The respondents were more likely to prefer less aggressive treatment for the older RA patient.

In addition to older age, rheumatoid factor negative RA was associated with being an inconsistent DMARD user. Seronegative patients have a better prognosis in terms of joint destruction, extra-articular disease and disease activity over time, and knowledge about the antibody status is therefore likely to have influenced treatment decisions.(27–29) Further, it was apparent from the EMR review that the rheumatologist questioned the validity of the RA diagnosis in at least some seronegative patients, and thus would be less likely to recommend DMARD treatment for these patients. Anti-CCP results were not commonly available to the rheumatologists in this clinic until 2005, and this could explain why RF was more strongly associated with consistent use than anti-CCP.

Inconsistent use was also associated with longer disease duration. Patients with long-standing disease could have been more likely to have experienced side effects or failure of DMARDs in the past, making introduction of a new DMARD more difficult. This assumption was supported by the finding of intolerance as one of the major reasons for inconsistent DMARD use in the EMR review.

Our study has some limitations. The first is that it is a single-center study, which potentially could decrease the generalizability of the results. However, several experienced board-certified rheumatologists provided care for the BRASS patients unlike some other cohorts where only a few selected doctors participate. Also, patients who enroll in BRASS may be a selective group who are more likely to use DMARDs consistently. Nevertheless, we thought it worthwhile to study inconsistent use in this patient population, as it is made up of patients who were all perceived by their caretaker to have RA at the time of inclusion, and for whom recommendations suggest DMARD treatment. The cohort of inconsistent DMARD users is not very large. However, this allowed us to perform a detailed chart review to uncover the reasons for inconsistent use. Moreover, the threshold that was chosen to define inconsistent use was chosen somewhat arbitrarily, and may have affected our results. Another potential issue is that treatment data were partially provided by patient self-report. However, patient reported DMARD use was previously found to correlate well with the medical record for current use in BRASS.(30) We assumed patients to be using DMARDs on missing time points and this assumption could have overestimated use. If we had assumed patients to not be using DMARDs on missing time points instead, the proportion of inconsistent users would have remained low (7.8%). We were unable to specifically report on the role of “rheumatologist choice” in determining inconsistent DMARD use. The rheumatologist could choose not to recommend DMARD use in patients with seemingly active disease because of the impression that pain was non-inflammatory or related to irreversible joint damage. The specific reasons why rheumatologists may choose not to use DMARDs could only be inferred from the available data. Lastly, we did not include data on the availability of medical insurance in the analyses. However, insurance issues were not mentioned in the EMR as a reason for inconsistent use in any of the 55 patients.

Strengths of our study include the longitudinal assessment of DMARD use, and that we had access to actual treatment data in a contemporary rheumatology practice. Inconsistent DMARD use was verified through EMR review, ensuring homogeneity of the study sample, and this allowed for a synthesis of quantitative and “semi-qualitative” data that offers a new perspective on DMARD treatment.

In conclusion, we found that 6.5% of the RA patients in a clinical cohort were inconsistently treated with DMARDs. Patients with higher age, longer disease duration and those who were rheumatoid factor negative were less likely to be consistent users. The most common reasons for inconsistent use were inactive disease and intolerance to treatment. Our finding that a substantial minority of inconsistent users become consistent users suggests a need for continued efforts to characterize such patients in order to identify these and work with them to find DMARDs that they can tolerate and find effective. Future analyses will explore to what degree inconsistent DMARD use has implications for disease outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: DHS is supported by a mentoring award from the NIH (K24 AR055989). The Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study receives support from Bristol Myers Squibb, Medimmune and Crescendo Bioscience.

References

- 1.Gaujoux-Viala C, Smolen JS, Landewe R, Dougados M, Kvien TK, Mola EM, et al. Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1004–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nam JL, Winthrop KL, van Vollenhoven RF, Pavelka K, Valesini G, Hensor EM, et al. Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:976–86. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:625–39. doi: 10.1002/acr.21641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, Buch M, Burmester G, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492–509. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmajuk G, Solomon DH, Yazdany J. Patterns of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug use in rheumatoid arthritis patients after 2002: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1927–35. doi: 10.1002/acr.22084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Söderlin MK, Lindroth Y, Jacobsson LT. Trends in medication and health-related quality of life in a population-based rheumatoid arthritis register in Malmo, Sweden. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1355–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokka T, Pincus T. Ascendancy of weekly low-dose methotrexate in usual care of rheumatoid arthritis from 1980 to 2004 at two sites in Finland and the United States. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1543–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez-Alvaro I, Descalzo MA, Carmona L. Trends towards an improved disease state in rheumatoid arthritis over time: influence of new therapies and changes in management approach: analysis of the EMECAR cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R138. doi: 10.1186/ar2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamanaka H, Inoue E, Singh G, Tanaka E, Nakajima A, Taniguchi A, et al. Improvement of disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis patients from 2000 to 2006 in a large observational cohort study IORRA in Japan. Mod Rheumatol. 2007;17:283–9. doi: 10.1007/s10165-007-0587-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeWitt EM, Lin L, Glick HA, Anstrom KJ, Schulman KA, Reed SD. Pattern and predictors of the initiation of biologic agents for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States: an analysis using a large observational data bank. Clin Ther. 2009;31:1871–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.08.020. discussion 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziegler S, Huscher D, Karberg K, Krause A, Wassenberg S, Zink A. Trends in treatment and outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis in Germany 1997–2007: results from the National Database of the German Collaborative Arthritis Centres. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1803–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.122101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung YK, Cho SK, Choi CB, Park SY, Shim J, Ahn JK, et al. Korean Observational Study Network for Arthritis (KORONA): establishment of a prospective multicenter cohort for rheumatoid arthritis in South Korea. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:745–51. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iannaccone CK, Lee YC, Cui J, Frits ML, Glass RJ, Plenge RM, et al. Using genetic and clinical data to understand response to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug therapy: data from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:40–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lillegraven S, Paynter N, Prince FH, Shadick NA, Haavardsholm EA, Frits ML, et al. Performance of matrix-based risk models for rapid radiographic progression in a cohort of patients with established rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:526–33. doi: 10.1002/acr.21870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pincus T, Swearingen C, Wolfe F. Toward a multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ): assessment of advanced activities of daily living and psychological status in the patient-friendly health assessment questionnaire format. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2220–30. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)42:10<2220::AID-ANR26>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:137–45. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bøyesen P, Haavardsholm EA, Ostergaard M, van der Heijde D, Sesseng S, Kvien TK. MRI in early rheumatoid arthritis: synovitis and bone marrow oedema are independent predictors of subsequent radiographic progression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:428–33. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sung YK, Yoshida K, Prince F, Frits ML, Choe JY, Chung WT, et al. Quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: cross-national comparison study between US and South Korea (abstract) Arthritis Rheum. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sokka T. Increases in use of methotrexate since the 1980s. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:S13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmajuk G, Schneeweiss S, Katz JN, Weinblatt ME, Setoguchi S, Avorn J, et al. Treatment of older adult patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis: improved but not optimal. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:928–34. doi: 10.1002/art.22890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tutuncu Z, Reed G, Kremer J, Kavanaugh A. Do patients with older-onset rheumatoid arthritis receive less aggressive treatment? Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1226–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.051144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraenkel L, Rabidou N, Dhar R. Are rheumatologists’ treatment decisions influenced by patients’ age? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:1555–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kastbom A, Strandberg G, Lindroos A, Skogh T. Anti-CCP antibody test predicts the disease course during 3 years in early rheumatoid arthritis (the Swedish TIRA project) Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1085–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.016808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Syversen SW, Gaarder PI, Goll GL, Ødegard S, Haavardsholm EA, Mowinckel P, et al. High anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide levels and an algorithm of four variables predict radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:212–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.068247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Longo FJ, Sanchez-Ramon S, Carreno L. The value of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: do they imply new risk factors? Drug News Perspect. 2009;22:543–8. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2009.22.9.1416992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon DH, Stedman M, Licari A, Weinblatt ME, Maher N, Shadick N. Agreement between patient report and medical record review for medications used for rheumatoid arthritis: the accuracy of self-reported medication information in patient registries. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:234–9. doi: 10.1002/art.22549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.