Personalised oncogenomics analysis revealed potential oncogene addiction of the AP-1 transcriptional complex in a chemo-refractory and MMR-deficient tumor from a patient with metastatic colon cancer. Based on this, treatment with the angiotensin receptor agonist irbesartan was initiated to target the renin–angiotensin system upstream of the AP-1 complex, leading to a profound and durable response.

Keywords: personalized medicine, AP-1 complex, irbesartan, chemo-refractory colon cancer, RNA expression analysis, mismatch repair defective

Abstract

Background

A patient suffering from metastatic colorectal cancer, treatment-related toxicity and resistance to standard chemotherapy and radiation was assessed as part of a personalized oncogenomics initiative to derive potential alternative therapeutic strategies.

Patients and methods

Whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing was used to interrogate a metastatic tumor refractory to standard treatments of a patient with mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer.

Results

Integrative genomic analysis indicated overexpression of the AP-1 transcriptional complex suggesting experimental therapeutic rationales, including blockade of the renin–angiotensin system. This led to the repurposing of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist, irbesartan, as an anticancer therapy, resulting in the patient experiencing a dramatic and durable response.

Conclusions

This case highlights the utility of comprehensive integrative genomic profiling and bioinformatics analysis to provide hypothetical rationales for personalized treatment options.

introduction

Cancers are diseases featuring genetic instability that results in genomically and behaviorally heterogeneous subgroups within each malignancy. This heterogeneity leads to variable responses to therapies among individuals with cancers of the same tumor subtype. The availability of genomic data has greatly enhanced our knowledge of tumor heterogeneity and has defined key driver pathways. These pathways in turn may provide insight into therapeutic rationales for individual malignancies, thereby increasing the potential for superior outcomes and a broader spectrum of drugs to consider for a given malignancy. Here, we present the case of a patient suffering from metastatic colorectal cancer, treatment-related toxicity and resistance to standard chemotherapy and radiation. Biopsies of this metastatic disease were characterized using a whole-genome analysis strategy. This strategy included integrative genomic analysis of whole-genome tumor and normal DNA sequencing and whole transcriptome sequence of tumor RNA. Our analysis revealed a minimally rearranged genome with a high mutational burden due to defective mismatch repair. Analysis of gene expression outliers identified high expression of FOS and JUN, components of the activating protein-1 (AP-1) complex, indicating its potential somatic activation. Based on this analysis, the possibility of treatment targeting the upstream activators of the AP-1 complex was raised and a trial of irbesartan was initiated. The patient's disease exhibited a profound and durable response to this treatment, which was selected based on genomic and outlier expression analyses.

methods

oversight

The study was approved by the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Committee (REB# H12-00137) and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before genomic profiling. Patient identity was anonymized within the research team and an identification code was assigned to the case for communicating clinically relevant information to physicians. The patients consented to potential publication of findings. Raw sequence data and downstream analytics were maintained within a secure computing environment.

histologic studies

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor sections underwent immunohistochemical analysis for expression of the MMR proteins MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 and MLH1 and the V600E mutant BRAF protein using standard protocols. For details, see the Methods section in supplementary Appendix S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing was carried out on the pretreatment tumor and blood, and whole-genome sequencing and whole transcriptome sequencing on the metastatic tumor resected from the L3 spinous region. The mean redundant depth of coverage for the pretreatment and metastatic tumors was 50- and 86-fold, respectively. Somatic point mutations, small insertions or deletions (indels) and copy-number alterations, detected in the tumor DNA but not in the germline, were identified (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). De novo assembly of genomic and transcriptomic data was carried out to detect rearrangements. Publicly available transcriptome sequencing data from normal colon tissue and colon adenocarcinoma were used to explore the expression profile of human genes and transcripts. A within-sample expression rank was also calculated to further infer significance to outlier gene expression levels. For details, see the Methods section in supplementary Appendix S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

sequencing data availability

Genomic and transcriptomic datasets have been deposited at the European Genome–phenome Archive (EGA, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/) under accession number EGAD00001001876.

results

case report

The patient was a previously healthy 67-year-old female when she presented in May 2010 with moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the ascending colon. Right hemicolectomy showed a stage III (pT3N1) adenocarcinoma. She did not tolerate adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin treatment due to significant neutropenia, necessitating dose reduction and G-CSF support. In addition, her course of adjuvant chemotherapy was attenuated to four of eight planned cycles due to severe neuropathy.

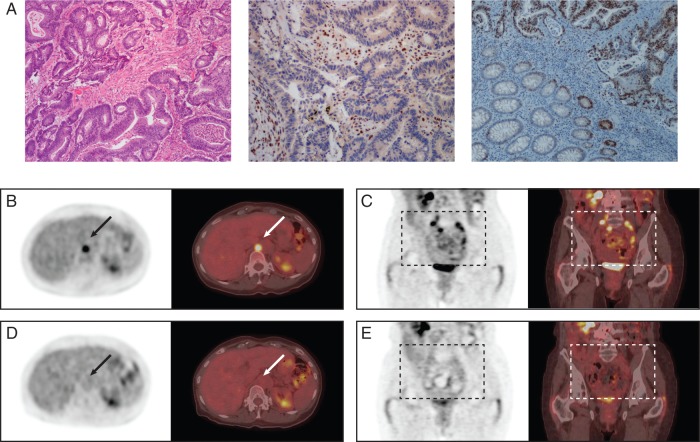

After completion of this adjuvant treatment, she proceeded with her active surveillance strategy as per standard guidelines with serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CT scan monitoring. In November 2012, she developed a recurrence near the right psoas muscle. This was excised in December with the pathology demonstrating moderately differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma (Figure 1A). Six lymph nodes were negative for disease, but the retroperitoneal resection margin was positive. Immunohistochemical workup showed an abnormal mismatch repair profile with loss of MLH1 protein, with no BRAF V600E mutation identified (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Pathology and positron emission tomography—computed tomography (PET/CT) scans. Hematoxylin and eosin staining (A, left) shows moderately differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma; immunohistochemistry for MLH1 shows loss of staining in tumor cell nuclei with retained staining in background inflammatory cells (centre); c-JUN immunohistochemistry shows strong expression in the tumor cells, note the normal colonic epithelium features staining of the crypt bases only (right). Pretreatment PET/CT scans (B–E) demonstrate fludeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the L3 spinous process (B) and in multiple lymph node areas including left supraclavicular, left mediastinal, retrocrural, retroperitoneal, para-aortic and bilateral iliac regions (C). Five weeks after treatment initiation with irbesartan (D and E). FDG activity has resolved in the affected areas.

She completed 45 Gy in 25 fractions of radiotherapy concurrent with capecitabine at 825 mg/m2 bid. Again, significant neutropenia led to capecitabine dose reduction.

She then relapsed with disease in the L3 spinous process in October 2013 and received 42 Gy of stereotactic radiotherapy in 10 fractions. In June 2014, the tumor recurred at the same site and she underwent palliative resection of the mass. At this point, she consented to undergo genomic analysis of the tumor resected from the L3 spinous process by the Personalized OncoGenomics (POG) initiative at the BC Cancer Agency (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The genomic analysis revealed overexpression of the FOS and JUN genes that encode the AP-1 transcriptional complex. The transcriptional expression rank of FOS and JUN was in the 98th and 100th percentile in relation to the TCGA colon cancer dataset, respectively, and 94th and 99th in a PAN-cancer comparison against multiple TCGA datasets. Immunohistochemical workup confirmed robust expression of c-JUN protein (Figure 1A). This indicated that mitigation of upstream factors leading to activation of this complex might provide a therapeutic advantage. One such pathway, the renin–angiotensin system, signals through the AP-1 complex and has been reported to be active in colorectal cancers [1]. Furthermore, antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of angiotensin blockade have been reported in human colon cancer cells [2, 3]. Supported by these findings, it was suggested that irbesartan could be a potential option due to the blockade of the renin–angiotensin pathway [4, 5].

The patient had a pretreatment baseline PET/CT scan and started irbesartan at a dose of 150 mg daily in December 2014. She had a follow-up PET/CT at 5 weeks and again at 3 months (Figure 1B–E). Before the therapy, her CEA was elevated at 18 (upper limit of normal 5). After 5 weeks of therapy, this value decreased to a CEA of 3.1. Furthermore, there was virtually a complete functional radiological resolution of her disease (Figure 1D and E). These results are maintained at the 10-month point with CEA at 1.4.

tumor genome analysis

Whole-genome sequencing identified 2183 somatic mutations (SNVs and Indels) predicted to affect protein-coding genes (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) in the metastatic tumor. The large number of genomic alterations was consistent with defective MMR arising from the loss of MLH1 observed using immunohistochemistry. In support of this observation, two inactivating truncating mutations in MLH1 (E199* and F70Afs) were detected. These mutations were also present in the primary tumor. No germline mutations known to contribute to a hypermutation phenotype were detected (data not shown). Furthermore, a large number of common mutations were observed between the pretreatment versus metastatic tumor (1599 somatic point mutations and indels), consistent with MMR deficiency in the primary lesion. Taken together, these data indicate that the hypermutation phenotype was likely an early somatic event in tumorigenesis facilitated by inactivation of MLH1.

Multiple genes encoding components of the AKT-PI3K-mTOR pathway were disrupted, including a previously reported mutation in PIK3CA (V344M, COSM253279). Mutation of this residue is thought to lead to increased PIK3CA activation through disruption of the interaction between PIK3CA and its regulatory subunit PIK3R1 [6]. PIK3R1 itself harbored two potentially damaging mutations (E65Kfs; S460_L531del). In addition, a frame-shift mutation in PTEN (L265fs) was observed, potentially leading to further activation of the AKT-PI3K-mTOR pathway.

Other potentially relevant lesions detected included two frame-shift mutations in APC (L598Wfs; T1556fs), inactivation of which is observed in over 50% of hypermutated colorectal cancers [7], a heterozygous mutation of uncertain significance in TP53 (A83V), a dominant negative mutation in the cell cycle regulator FBXW7 (R479Q, COSM1154291) and potentially inactivating homozygous mutations in genes encoding the TGF-β pathway components BMPR2 (N583Tfs) and SMAD2 (G367D). In a cohort of sequenced colorectal cancers, mutation of APC, TP53, PIK3CA and FBXW7 were found to be associated with aggressive disease [7]. Finally, a potentially inactivating heterozygous mutation in AGTR1 (S338Ffs), which encodes the Angiotensin II receptor, was detected.

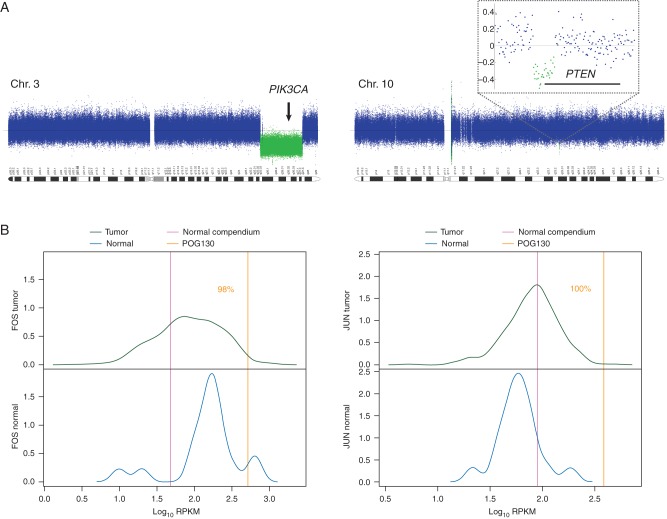

Genome-wide copy-number analysis revealed no copy-number gains of known clinical or therapeutic relevance (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Notably, FOS and JUN are not amplified in the tumor. However, single copy losses in chromosomes 3 and 10 were detected in areas harboring the entire coding region of PIK3CA and the first 2 exons of PTEN, respectively (Figure 2A), leading to hemizygosity of the respective mutations in these genes, as described above. Structural analysis from de novo genome assembly revealed 53 rearrangements (translocations, inversions, deletions and duplications) none of which are known to contribute to disease initiation or progression, or to be of utility in therapeutic decision-making (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 2.

CNV and expression analysis. CNV plots of chromosomes 3 and 10 in the colonic adenocarcinoma (A); single copy loss in a region containing PIK3CA (left); single copy loss of approximately 20 kb deletes exons 1 and 2 of PTEN (right and inset). Density plots showing relative gene expression levels compared with colon adenocarcinoma (B) for FOS (left) and JUN (right). Green curve indicates expression range in tumor tissue, blue curve depicts expression range in normal tissue, yellow line shows relative expression level in patient tumor tissue, and pink line indicates relative expression level in normal compendium.

transcriptome analysis

Among the most significantly differentially expressed genes were those encoding the founding members of two proto-oncogene families, FOS and JUN. Together c-FOS and c-JUN comprise the AP-1 transcriptional complex, which is known to be a key regulator of disease initiation and progression in many cancer types, including colorectal cancer [8, 9]. Expression levels of FOS and JUN were 10- and 4-fold greater than for normal colon tissue, and 3.7- and 4-fold when compared with the mean expression of the malignant colon adenocarcinoma cohort, respectively (equivalent to the 98th and 100th percentile of expression, respectively). Both genes were ranked in the 100th percentile for gene expression within the tumor transcriptome (Figure 2B, supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

discussion

Innovation in genomic technology in the last decade has greatly advanced the progress of personalized/precision medicine. This case highlights the utility of transcriptome and expression data in combination with genomic mutational data to identify potential therapeutic targets for oncology patients. The Personalized OncoGenomic (POG) Program utilizes parallel sequencing technology and transcriptome information providing a comprehensive map of expressed mutations which provides more information than the standard mutation panels that are currently available commercially. Given that cancer is a disease of genetic instability, this case highlights the significant impact on outcomes when utilizing this technology and repurposing of medications.

This case demonstrated outlier expression of FOS and JUN that was suggestive of oncogene addiction and therefore was potential therapeutic axis for a targeted therapy. Irbesartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker, has demonstrated previous JUN inhibition at the transcriptional and protein level [4, 5]. Colorectal carcinogenesis is activated through the AP-1 transcription factors. The two proto-oncogenes, JUN and FOS, are part of this pathway and have previously been demonstrated to be dysregulated in colorectal carcinomas when compared with normal colon mucosa [10–12]. Pre-clinical models using inhibitors of this pathway have demonstrated some efficacy [13, 14]. In addition to the high expression of FOS and JUN, it is also noted that both the primary and metastatic tumors harbored a heterozygous loss of function allele in the angiotensin receptor type 1 (AGTR1). Although not functionally characterized in the tumor, it is intriguing to postulate that haploinsufficiency of AGTBR1 might have further sensitized the pathway to blockade, contributing to the dramatic clinical response. Targeting this pathway was a rational approach, given the heterozygous loss of function of AGTR1 in combination with the dramatic overexpression of the AP1 complex in this patient. It should be noted that AKT pathway inhibitors were also considered as a therapeutic rationale in this case due to potential activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway in the tumor due to the observed mutations in PIK3CA, PIK3R1 and PTEN.

The somatic mutations in MLH1 explain the significant number (∼2100) of somatic protein-coding alterations seen in the genome. Hypermutated tumors have been shown to respond to immunotherapy, and the rapid response to the intervention reported herein is reminiscent of the early serum tumor marker responses (between day 14 and day 28) that were seen in mismatch repair-deficient tumors treated with PD1 blockade and predictive of both progression-free and overall survival [15]. The role of immune modulation is intriguing based on the critical roles of AP-1 in leukocyte activation and differentiation in the immune system [16]. Irbesartan has been shown to inhibit AP-1 DNA binding and transcriptional activity in a dose-dependent manner [4]. Irbesartan inhibited production of cytokines by activated T cells and inhibited activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase. Further, ARBs have demonstrated preservation of T-cell and monocyte function in patients with multiple organ failure [17]. Together, these data are compatible with the notion that Irbesartan may modulate T-cell function via the AP-1 pathway and it is possible that the patient's dramatic response was related to immune effects that [18, 19] contributed to the therapeutic benefit seen in this mismatch repair-deficient tumor.

The TGF-β superfamily is mutated in MSI-H tumors, specifically TGFRBR2 and ACVR2A, which may be important for the development of colorectal cancer [20]. Negative feedback may cause a paradoxical increase in TGFB1 expression, AP-1 has been shown to act on the TGFB1 promoter [21]. In our patient, transcriptome analysis indicated that TGFB1 expression was high, being in the 83rd percentile among colorectal adenocarcinomas (TCGA COAD), and was increased relative to normal colon. Attenuation of non-canonical TGF-β signaling has been proposed as a mechanism by which angiotensin II blockade prevents and stabilizes arterial aneurysms in patients with germline aberrations in the TGF-β pathway, causing hereditary connective tissue and aneurysmal disease [22]. Furthermore, it has established roles in regulation of immune response that have made it an attractive anticancer target for drug development [18, 19]. Circulating TGFB1 concentrations are elevated in Marfan syndrome and decrease after administration of another ARB, losartan, and also β-blocker therapies [23, 24]. The effect of angiotensin II inhibitors on the TGF-β pathway may also have contributed to the activity of irbesartan in this case, directly on the tumor and/or in relation to the immune cell response.

Repurposing drugs in oncology provides another therapeutic strategy [25]. There has been some limited success such as the use of thalidomaide in myeloma [26], aspirin in colorectal cancer or metformin in breast cancer [27]. This case highlights the use of whole-genome analysis, including transcriptome data, to identify new candidate therapeutic targets. However, many genomics platforms offer mutation analysis but lack expression information. With comprehensive integrative profiling and bioinformatics analysis, therapy can be made more precise and can provide excellent, and perhaps unexpected, results. As genomic technology linked to clinical implementation advances, further therapeutic options with the possibility of repurposing medications will be realized for more oncology patients.

funding

This research was generously funded through unrestricted philanthropic donations received through the BC Cancer Foundation. MAM acknowledges infrastructure investments from the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the University of British Columbia and the support of the Canada Research Chairs program. No grant numbers applied.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients and families who participated in this study. We also thank and acknowledge all of the researchers and clinicians who are not listed as authors but worked to make this study possible, particularly Dr Charles Fisher (MD, MHSC, FRCSC) of the Vancouver Spine Surgery Institute, Vancouver General Hospital (VGH), for facilitating surgical tumor tissue extraction and Christine Chow (GPEC) for technical work on the histologic studies. The results shown here are in part based upon data generated by the TCGA Research Network: http://cancergenome.nih.gov/.

references

- 1.Kuniyasu H. Multiple roles of angiotensin in colorectal cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2012; 3: 150–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee LD, Mafura B, Lauscher JC et al. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of telmisartan in human colon cancer cells. Oncol Lett 2014; 8: 2681–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engineer DR, Burney BO, Hayes TG, Garcia JM. Exposure to ACEI/ARB and beta-blockers is associated with improved survival and decreased tumor progression and hospitalizations in patients with advanced colon cancer. Transl Oncol 2013; 6: 539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng SM, Yang SP, Ho LJ et al. Irbesartan inhibits human T-lymphocyte activation through downregulation of activator protein-1. Br J Pharmacol 2004; 142: 933–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu ZS, Wang JM, Chen SL. Mesenteric artery remodeling and effects of imidapril and irbesartan on it in spontaneously hypertensive rats. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10: 1471–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudd ML, Price JC, Fogoros S et al. A unique spectrum of somatic PIK3CA (p110alpha) mutations within primary endometrial carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 1331–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012; 487: 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kappelmann M, Bosserhoff A, Kuphal S. AP-1/c-Jun transcription factors: regulation and function in malignant melanoma. Eur J Cell Biol 2014; 93: 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashida R, Tominaga K, Sasaki E et al. AP-1 and colorectal cancer. Inflammopharmacology 2005; 13: 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magrisso IJ, Richmond RE, Carter JH et al. Immunohistochemical detection of RAS, JUN, FOS, and p53 oncoprotein expression in human colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Lab Invest 1993; 69: 674–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W, Hart J, McLeod HL, Wang HL. Differential expression of the AP-1 transcription factor family members in human colorectal epithelial and neuroendocrine neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol 2005; 124: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Birkenbach M, Hart J. Expression of Jun family members in human colorectal adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2000; 21: 1313–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S, Lee DK, Yang CH. Inhibition of fos–jun–DNA complex formation by dihydroguaiaretic acid and in vitro cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. Cancer Lett 1998; 127: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suto R, Tominaga K, Mizuguchi H et al. Dominant-negative mutant of c-Jun gene transfer: a novel therapeutic strategy for colorectal cancer. Gene Ther 2004; 11: 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2509–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foletta VC, Segal DH, Cohen DR. Transcriptional regulation in the immune system: all roads lead to AP-1. J Leukoc Biol 1998; 63: 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winfield RD, Southard RE, Turnbull IR et al. Angiotensin inhibition is associated with preservation of T-cell and monocyte function and decreases multiple organ failure in obese trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221: 486–494.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connolly EC, Freimuth J, Akhurst RJ. Complexities of TGF-beta targeted cancer therapy. Int J Biol Sci 2012; 8: 964–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wrzesinski SH, Wan YY, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-beta and the immune response: implications for anticancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 5262–5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim TM, Laird PW, Park PJ. The landscape of microsatellite instability in colorectal and endometrial cancer genomes. Cell 2013; 155: 858–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashiwagi I, Morita R, Schichita T et al. Smad2 and Smad3 inversely regulate TGF-beta autoinduction in clostridium butyricum-activated dendritic cells. Immunity 2015; 43: 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindsay ME, Dietz HC. The genetic basis of aortic aneurysm. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med 2014; 4: a015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campistol JM, Inigo P, Jimenez W et al. Losartan decreases plasma levels of TGF-beta1 in transplant patients with chronic allograft nephropathy. Kidney Int 1999; 56: 714–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matt P, Schoenhoff F, Habashi J et al. Circulating transforming growth factor-beta in Marfan syndrome. Circulation 2009; 120: 526–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V et al. Apoptotic signaling induced by immunomodulatory thalidomide analogs in human multiple myeloma cells: therapeutic implications. Blood 2002; 99: 4525–4530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang T, Yang Y, Liu S. Association between metformin therapy and breast cancer incidence and mortality: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Breast Cancer 2015; 18: 264–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1596–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.