Significance

We present direct, field-based measurements of low nitrogen fixation rates in the eastern tropical South Pacific (ETSP) Ocean demonstrating that N2 fixation plays a minor role supporting export production regionally. These results are in contrast to indirect estimates that the highest global rates of N2 fixation occur in the ETSP. The low N2-fixation rates occur in a region with relatively high surface ocean phosphate concentrations (and low nitrate concentrations) but where atmospheric iron deposition rates are diminishingly low. Consequently, these results indicate that the ETSP hosts a minor fraction of global N2-fixation fluxes and that low nitrate to phosphate concentration ratios alone are insufficient to support high N2-fixation fluxes.

Keywords: nitrogen fixation, eastern tropical south Pacific, nitrogen budgets, nitrate, nitrogen isotopes

Abstract

An extensive region of the Eastern Tropical South Pacific (ETSP) Ocean has surface waters that are nitrate-poor yet phosphate-rich. It has been proposed that this distribution of surface nutrients provides a geochemical niche favorable for N2 fixation, the primary source of nitrogen to the ocean. Here, we present results from two cruises to the ETSP where rates of N2 fixation and its contribution to export production were determined with a suite of geochemical and biological measurements. N2 fixation was only detectable using nitrogen isotopic mass balances at two of six stations, and rates ranged from 0 to 23 µmol N m−2 d−1 based on sediment trap fluxes. Whereas the fractional importance of N2 fixation did not change, the N2-fixation rates at these two stations were several-fold higher when scaled to other productivity metrics. Regardless of the choice of productivity metric these N2-fixation rates are low compared with other oligotrophic locations, and the nitrogen isotope budgets indicate that N2 fixation supports no more than 20% of export production regionally. Although euphotic zone-integrated short-term N2-fixation rates were higher, up to 100 µmol N m−2 d−1, and detected N2 fixation at all six stations, studies of nitrogenase gene abundance and expression from the same cruises align with the geochemical data and together indicate that N2 fixation is a minor source of new nitrogen to surface waters of the ETSP. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that, despite a relative abundance of phosphate, iron may limit N2 fixation in the ETSP.

Rates of marine photosynthesis significantly influence the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, particularly on glacial–interglacial time scales (1). In broad regions of the low latitude ocean, rates of photosynthesis are thought to be limited by the availability of fixed nitrogen (N), thus restricting the biological sequestration of carbon in the deep ocean (2). The inventory of fixed N in the ocean is regulated by the balance between the principal, biologically mediated N sources and sinks, di-nitrogen (N2) fixation, and denitrification. Despite the critical importance of the fixed N inventory in regulating photosynthesis, the spatial distribution of N fluxes to the ocean remain poorly constrained.

For decades, both geochemical and biological analyses (3–6) have pointed to a spatial decoupling of N fluxes to and from the ocean, with the highest rates of N2 fixation documented in the tropical North Atlantic and the largest N losses concentrated in the Eastern tropical Pacific and Arabian Sea. This spatial decoupling of N inputs and outputs corresponds to a temporal decoupling, requiring the time scale of ocean circulation for N2 fixation to respond to changes in rates of denitrification and vice versa. Despite this apparent decoupling in the modern ocean, paleoceanographic evidence indicates that N fluxes to and from the ocean have been closely balanced at least over the past 20 kyr (7, 8), although more recent work suggests transient imbalances may have occurred (9). Although N loss in the ocean is largely constrained to the sediments and water column oxygen deficient zones (ODZs) in the Eastern Pacific and Arabian Sea, similar constraints on the location of N2-fixation fluxes to the ocean are lacking and thus the degree to which marine N sources and sinks have been coupled through time remain uncertain.

Both remote sensing (10) and biogeochemical modeling (11) have suggested that the highest rates of N2 fixation may occur in the surface waters of the Eastern and Central tropical Pacific, which carry the geochemical signatures of N loss occurring in nearby sediments and water column ODZs (5, 6, 11). This spatial coupling of N inputs and losses in the ocean would provide the proximity necessary to allow feedbacks within the N cycle to respond to the changes in the N inventory on the decade- to hundred-year time scales apparently required by the paleoceanographic record (8, 11). Furthermore, these findings are consistent with paleoceanographic evidence for denitrification influencing the location of N2-fixation fluxes (12). Nonetheless, these indirect estimates of high N2-fixation rates occurring in the Eastern tropical Pacific have remained controversial in part because they challenge the well-documented high iron requirement of the enzyme nitrogenase, which carries out N2 fixation (13, 14). The surface waters of the Central and Eastern tropical South Pacific (ETSP) receive some of the lowest atmospheric dust fluxes (15), raising the question how the largest global marine N2-fixation fluxes (11) could occur in a region where iron sources are scarce. Indeed, previous field studies found N2-fixation rates that were at or below detection limits and inferred that iron limits primary productivity in the region (16). Other models of the global distribution of marine N2-fixation fluxes emphasize the iron requirements of diazotrophs and shift the bulk of predicted N2-fixation fluxes to the Southwest Pacific Ocean proximal to larger atmospheric dust sources (17–19).

Given the uncertainty in the spatial distribution of N2 fixation in the global ocean, field campaigns making direct measurements of N fluxes to the ocean remain a priority, in particular in the expansive ETSP gyre, where few such measurements have been made (20). Here, we present a suite of measurements from the ETSP gyre, collected between 80°W to 100°W along 20°S (Fig. S1), evaluating N2 fixation on ∼1- to 3-d time scales, including short-term (i.e., 24 h) incubation-based fixation rates. N2-fixation rates and their contribution to export production were also evaluated with a N isotope mass balance which compared the isotopic composition of sinking particulate N (PNsink) collected for 35–70 h in floating sediment traps with that of subsurface Together with a parallel analysis of the abundance and expression of the dinitrogenase reductase iron protein encoded by the NifH gene from the same cruises (21), as well as measurements of the isotopic composition of PNsink collected over 13 mo in a deep-moored sediment trap (22), these datasets constrain the role of N2 fixation in the ETSP gyre.

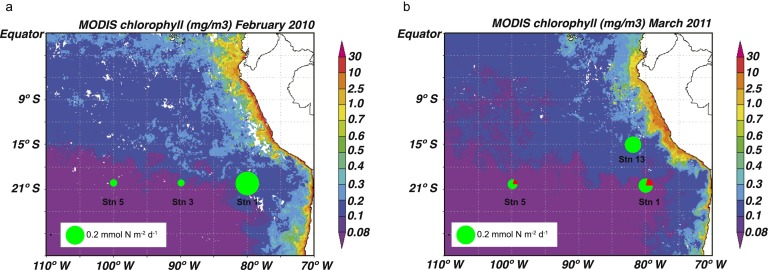

Fig. S1.

Fractional contribution of subsurface NO3+NO2 and N2 fixation to export production in the ETSP based on the results of the δ15N budgets. Station numbers are overlain upon Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) surface ocean chlorophyll for February 2010 (A) and March 2011 (B). The relative magnitude of the PNsink flux is represented by the area of the circle, with the fraction of the PNsink flux supported by subsurface in green and the fraction supported by N2 fixation in red.

Results

N2-Fixation Rates and Their Contribution to Export Production in the ETSP.

N2-fixation rates calculated with geochemical methods track the distinct imprints that diazotrophs leave on water column nutrient stoichiometry and isotopic composition. The approach used here relies on the unique isotopic signature with atmospheric N2 as the reference) of diazotrophic biomass [δ15NNfix = −2–0‰ (23, 24)], which is low compared with that of mean ocean nitrate [δ15NNO3, ∼5‰ (25)]. Because the δ15N of the two dominant sources of new N to surface waters [subsurface + nitrite and N2 fixation] have distinct δ15N values, the δ15N of these two sources can be used together with the δ15N of PNsink (δ15NPNsink) to construct a two end-member mixing model (δ15N budget) to estimate the relative importance of each for supporting export production (26–28) (Fig. S2). The fractional importance of N2 fixation for supporting export production (x) can be expressed as

| [1] |

Rearranging and solving for x yields

| [2] |

Multiplying x by the PNsink flux provides a time-averaged N2-fixation rate that can be compared with short-term N2-fixation rate measurements.

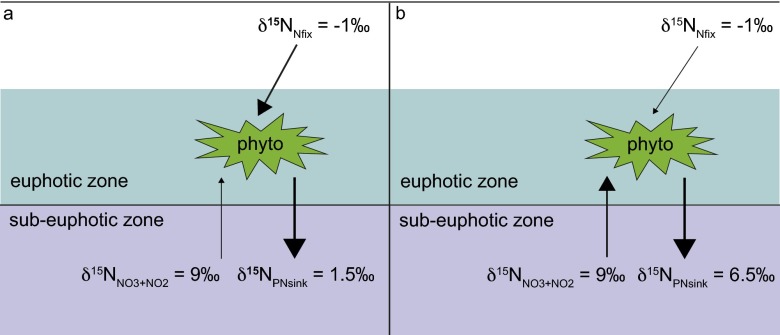

Fig. S2.

Idealized δ15N budget. In a δ15N budget the isotopic composition of the quantitatively dominant export flux from the euphotic zone (“δ15NPNsink”) reflects the proportional contributions of the two dominant sources of new nitrogen to surface waters, N2 fixation (“Nfix”) and subsurface nitrate+nitrite (NO3+NO2), which in this example have been assigned δ15N of −1‰ and 9‰, respectively. In the case where the δ15NPNsink = 1.5‰, 75% of export production is supported by N2 fixation and 25% from NO3+NO2 (A); in the case where the δ15NPNsink = 6.5‰, 75% of export production is supported by NO3+NO2 and 25% from N2 fixation (B).

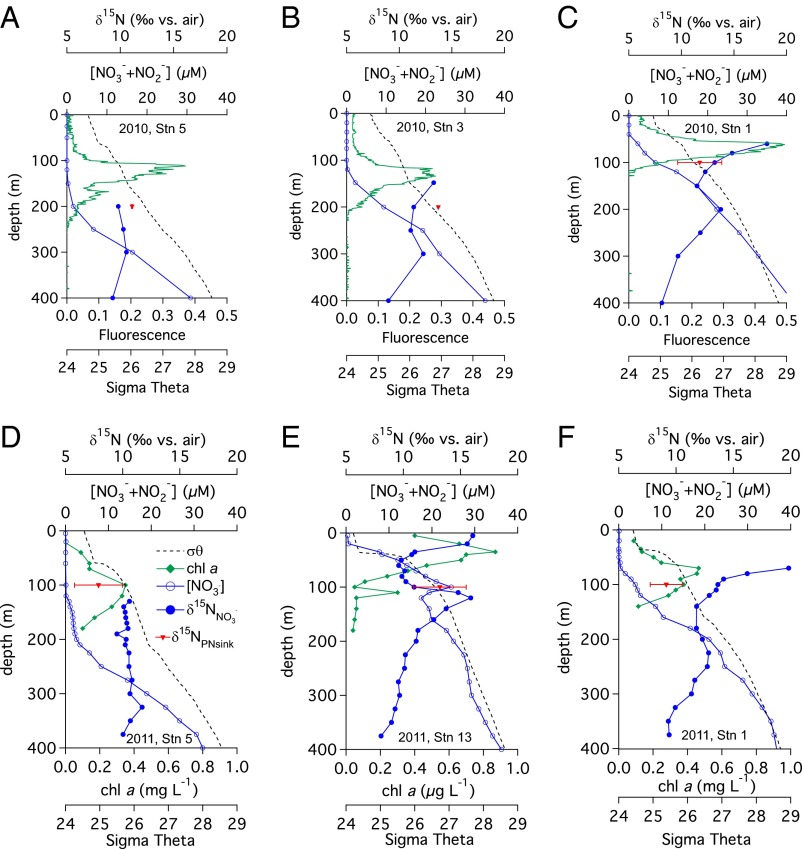

Floating sediment trap δ15NPNsink and water column δ15NNO3+NO2 measurements from two cruises to the ETSP (January to February 2010 and March to April 2011) were used to construct the δ15N budgets (Table 1 and Fig. S1). This approach depends on the careful characterization of both the δ15NNfix as well as the δ15NNO3+NO2 end-members. The δ15NNfix end-member is constrained by field measurements of diazotrophic biomass δ15N that range between approximately −2‰ and 0‰ (23, 24); lower δ15NNfix values result in a lesser contribution of N2 fixation to export production (Eq. 2). Here, we take δ15NNfix = −1‰. Uncertainty in the δ15NNO3+NO2 end-member largely depends on the degree to which δ15NNO3+NO2 varies with depth in the upper thermocline and whether or not there is unconsumed in surface waters. At these stations, mixed layer concentrations of were typically at or below detection limits (0.05 µM) (except in 2011 at the more northern Station 13, where the mixed-layer concentration was between 0.3 and 0.6 µM) and increased rapidly below the base of the euphotic zone (Fig. 1 and Table S1). Effectively complete consumption of surface water in this region of the ETSP alleviates concerns with the choice of isotope effect used for assimilation in δ15N budget calculations (29, 30). Profiles at eastern stations (i.e., Stations 1 and 13) show isotopic features indicative of dissimilatory reduction occurring in the nearby ODZs of the ETSP (Fig. 1) (6, 31–33). Additional increases in δ15NNO3+NO2 coincident with the deep chlorophyll a maximum (Stations 1, 3, and 13; Fig. 1) indicate that assimilation elevated the δ15NNO3+NO2 within and immediately below the base of the euphotic zone (34, 35).

Table 1.

Results of the δ15N budgets

| Year and station | δ15NNO3+NO2 (‰) | δ15NPNsink (‰) | fnfix (%) | Rnfix δ15N budget (µmol N m−2 d−1) | Rnfix short-term incub (μmol N m−2 d−1) | Short-term incubation | |

| fnfix (%) | δ15NPNsink (‰) | ||||||

| 2010 | |||||||

| Station 1 | 11.5 ± 0.2 | 11.7 ± 2.1 | 0 ± 15 | 0 ± 48 | 37 ± 17 | 12 | 10.0 |

| Station 3 | 11.1 ± 0.01 | 13.7 | 0 | 0 ± 0 | 98 ± 129 | 362 | −1 |

| Station 5 | 9.8 ± 0.9 | 11.1 ± 0.1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 51 ± 20 | 170 | −1 |

| 2011 | |||||||

| Station 1 | 11.8 ± 0.1 | 9.2 ± 1.4 | 21 ± 10 | 24 ± 13 | 23 ± 24 | 20 | 9.2 |

| Station 5 | 10.1 ± 0.0 | 7.9 ± 2.1 | 20 ± 19 | 11 ± 10 | 86 ± 9 | 160 | −1 |

| Station 13 | 9.6 ± 0.9 | 13.2 ± 2.3 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 61 ± 22 | 39 | 5.4 |

Results include δ15NNO3+NO2 end-member (±1 SD), measured δ15NPNsink (±1 SD), the calculated fractional contribution of N2 fixation to export production (fnfix; %) (±1 SD), and N2-fixation rate (Rnfix δ15N budget; µmol N m−2 d−1) (±1 SD), as well as N2-fixation rates from short-term incubations (Rnfix short-term incub; μmol N m−2 d−1) (±1 SD). The last two columns report the fraction of the PNsink flux that would be supported by N2 fixation as well as the δ15NPNsink that would be expected assuming the short-term N2-fixation rate; see Discussion for details.

Fig. 1.

Biogeochemical characterization of the ETSP upper thermocline. Water column profiles of potential density (dashed black line), concentration (open circles), δ15NNO3+NO2 (filled circles), δ15NPNsink with error bars (±1 SD) (filled triangles), and CTD fluorescence trace from the 2010 cruise (solid green line) or discrete chlorophyll a measurements from the 2011 cruise (filled diamonds) for 2010 Station 5 (100°W, 20°S) (A), 2010 Station 3 (90°W, 20°S) (B), 2010 Station 1 (80°W, 20°S) (C), 2011 Station 5 (100°W, 20°S) (D), 2011 Station 13 (82°W, 15°S) (E), and 2011 Station 1 (80°W, 20°S) (F).

Table S1.

Summary of station location, sampling depths, and biogeochemical parameters at each station

| Depth, m | Sigma theta | [NO3−+NO2−], µM (±1 SD) | NO3−+NO2−δ15N, ‰ vs. air (±1 SD) | [O2], µmol/kg | [PNsusp], µM | PNsusp δ15N, ‰ vs. air | Trap δ15N, ‰ vs. air (±1 SD) | Length of trap deployment, h |

| Cruise year 2010 | ||||||||

| Station 1 (20° S, 80° W) | ||||||||

| 0 | 24.773 | 0.04 (0) | 231.20 | 0.54 | 11.2 | |||

| 20 | 24.856 | 0.05 (0) | 231.18 | |||||

| 40 | 25.273 | 0.05 (0) | 239.67 | 0.56 | 9.5 | |||

| 60 | 25.627 | 2.3 (0) | 18.1 (0.2) | 252.16 | ||||

| 80 | 25.834 | 4.1 (0.3) | 14.8 (0.03) | 242.31 | 0.90 | 8.8 | ||

| 100 | 26.074 | 6.7 (0.02) | 13.2 (0.2) | 233.47 | *11.7 (2.1) | 35 | ||

| 120 | 26.471 | 12.1 (0.2) | 12.3 (0.02) | 219.82 | 0.28 | 8.1 | ||

| 150 | 26.871 | 17.5 (2.0) | 11.5 (0.2) | 173.97 | 0.24 | 6.5 | ||

| 200 | 27.351 | 22.3 (1.3) | 13.8 (0.2) | 51.30 | 0.21 | 10.5 | ||

| 250 | 27.758 | 28 (0.1) | 11.8 (0.2) | 16.03 | 0.25 | 5.4 | ||

| 300 | 28.121 | 32.8 (0.1) | 9.7 (0.0) | 20.31 | 0.33 | 7.3 | ||

| 400 | 28.75 | 41.9 (0.1) | 8.1 (0.2) | 22.17 | 0.23 | 10.4 | ||

| Station 3 (19.59° S, 89.59° W) | ||||||||

| 0 | 24.753 | 0.06 (0.01) | 225.76 | 0.41 | 8.2 | |||

| 20 | 24.885 | 0.04 (0.02) | 224.97 | 0.45 | 7.4 | |||

| 40 | 25.026 | 0.04 (0.0) | 225.50 | 0.36 | 13.2 | |||

| 60 | 25.36 | 0.02 (0.01) | 226.79 | |||||

| 75 | 25.494 | 0.03 (0.0) | 238.03 | 0.32 | 8.7 | |||

| 100 | 25.7 | 0.02 (0.0) | 235.59 | |||||

| 120 | 25.824 | 0.2 (0.0) | 230.93 | 0.41 | 7.3 | |||

| 148 | 26 | 2.2 (0.03) | 13.3 (0.1) | 223.09 | ||||

| 200 | 26.687 | 9.4 (0.1) | 11.4 (0.05) | 203.72 | 0.26 | 7.3 | *13.7 | 37 |

| 250 | 27.403 | 19.3 (0.4) | 11.1 (0.01) | 127.64 | 0.30 | 4.3 | ||

| 300 | 27.922 | 23.5 (1.3) | 12.3 (0.0) | 32.95 | 0.15 | 9.9 | ||

| 400 | 28.661 | 35.1 (1.0) | 9 (0.0) | 36.47 | 0.08 | 8.5 | ||

| Station 5 (19.59° S, 100° W) | ||||||||

| 0 | 24.671 | 0.02 (0.0) | 217.76 | 0.27 | 10.8 | |||

| 25 | 24.777 | 0.02 (0.0) | 218.00 | 0.42 | 7.6 | |||

| 50 | 24.917 | 0.02 (0.0) | 217.71 | 0.37 | 7.8 | |||

| 100 | 25.497 | 0.03 (0.01) | 229.21 | 0.48 | 7.6 | |||

| 120 | 25.715 | 0.02 (0.01) | 223.23 | 0.30 | 7.8 | |||

| 150 | 25.899 | 0.3 (0.05) | 218.87 | 0.38 | 9.1 | |||

| 200 | 26.44 | 1.6 (0.03) | 9.8 (0.9) | 215.80 | 0.32 | 6.0 | *11.1 (0.1) | 65 |

| 250 | 26.977 | 6.6 (0.1) | 10.3 (0.2) | 203.17 | ||||

| 300 | 27.639 | 16.4 (0.02) | 10.6 (0.1) | 158.73 | 0.20 | 9.8 | ||

| 400 | 28.538 | 30.9 (0.3) | 9.3 (0.02) | 47.31 | 0.85 | 6.8 | ||

| Cruise year 2011 | ||||||||

| Station 1 (20° S, 80° W) | ||||||||

| 2 | 24.429 | 0.1 (0.06) | 212.13 | 0.41 | 8.7 | |||

| 20 | 24.501 | 0.1 (0.01) | 212.25 | 0.36 | 8.9 | |||

| 35 | 24.58 | 0 (0) | 214.81 | |||||

| 40 | 25.168 | 0.06 (0.01) | 241.14 | 0.45 | 9.5 | |||

| 50 | 25.412 | 0.05 (0) | 245.60 | 0.45 | 8.4 | |||

| 60 | 25.612 | 0.3 (0.07) | 241.63 | |||||

| 70 | 25.767 | 0.4 (0.01) | 19.8 (0.6) | 234.04 | ||||

| 80 | 25.846 | 1.5 (0.08) | 16.2 (0.4) | 224.98 | ||||

| 90 | 25.929 | 2.9 (0.04) | 14.2 (0.2) | 220.14 | ||||

| 100 | 25.992 | 3.9 (0.04) | 13.7 (0.1) | 216.74 | 0.23 | 9.5 | *9.2 (1.4) | 39 |

| 110 | 26.06 | 4.4 (0) | 13.5 (0.2) | 213.39 | ||||

| 120 | 26.149 | 5.1 (0.03) | 12.9 (0.1) | 207.86 | ||||

| 140 | 26.332 | 8.6 (0.03) | 11.8 (0.1) | 196.76 | ||||

| 160 | 26.498 | 10.4 (0.01) | 187.14 | |||||

| 180 | 26.855 | 16.6 (0.04) | 11.8 (0.1) | 139.05 | ||||

| 200 | 27.076 | 21 (0.5) | 12.3 (0.1) | 90.23 | 0.13 | 7.9 | *7.5 (3.9) | 39 |

| 225 | 27.388 | 23.7 (0.4) | 12.8 (0.02) | 41.23 | ||||

| 250 | 27.634 | 24.7 (0.2) | 12.7 (0.1) | 21.51 | ||||

| 275 | 27.857 | 28.9 (0.5) | 11.6 (0.1) | 9.27 | ||||

| 300 | 28.036 | 31 (0.2) | 11.3 (0.2) | 8.89 | 0.12 | 10.4 | ||

| 325 | 28.226 | 33.4 (0.6) | 9.9 (0.2) | 9.91 | ||||

| 350 | 28.394 | 35.4 (0.1) | 9.3 (0.2) | 14.92 | ||||

| 375 | 28.557 | 36.1 (0.1) | 9.4 (0.2) | 20.71 | ||||

| Station 5 (20° S, 100° W) | ||||||||

| 5 | 24.572 | 0.03 (0.04) | 213.36 | 0.49 | 8.1 | |||

| 20 | 24.653 | 0.1 (0.06) | 213.71 | 0.38 | 4.9 | |||

| 40 | 24.75 | 0.04 (0.05) | 213.61 | 0.45 | 7.4 | |||

| 60 | 24.975 | 0.03 (0.04) | 218.76 | |||||

| 70 | 25.325 | 234.21 | ||||||

| 100 | 25.745 | 0.1 (0.05) | 234.50 | 0.33 | 7.3 | *7.9 (2.1) | 70 | |

| 120 | 25.9 | 0.2 (0.06) | 227.47 | |||||

| 130 | 25.969 | 0.8 (0.08) | 10.6 | 226.48 | ||||

| 140 | 26.033 | 1.1 (0.02) | 10.1 (0.0) | 220.40 | ||||

| 150 | 26.088 | 1.6 (0.06) | 10.2 (0.1) | 217.85 | ||||

| 160 | 26.143 | 1.7 (0.06) | 10.3 (0.2) | 214.75 | ||||

| 170 | 26.194 | 1.8 (0.02) | 10.4 (0.1) | 214.46 | ||||

| 180 | 26.251 | 2 (0.08) | 10.5 (0.3) | 214.13 | ||||

| 190 | 26.298 | 2.2 (0.08) | 9.5 (1.2) | 213.76 | ||||

| 200 | 26.368 | 2.6 (0.2) | 10.3 (0.5) | 211.22 | 0.22 | 6.3 | *6.3 (1.6) | 70 |

| 210 | 26.427 | 3.4 (0.03) | 10.2 (0.4) | 211.61 | ||||

| 225 | 26.675 | 5.6 (0.2) | 10.6 (0.5) | 205.86 | ||||

| 250 | 26.967 | 8.3 (0.04) | 10.6 (0.4) | 194.63 | ||||

| 275 | 27.271 | 14.5 (0.5) | 10.8 (0.2) | 169.52 | ||||

| 300 | 27.575 | 19 (0.1) | 10.6 (0.8) | 109.36 | 0.24 | 5.8 | ||

| 325 | 27.859 | 23.4 (0.3) | 11.7 (0.1) | 52.99 | ||||

| 350 | 28.133 | 26.6 (0.1) | 10.7 (0.1) | 65.82 | ||||

| 375 | 28.36 | 30.6 (0.2) | 10 (0.5) | 44.12 | ||||

| 400 | 28.555 | 32 (0.4) | 42.62 | 0.15 | 6.1 | |||

| Station 13 (15° S, 82° W) | ||||||||

| 5 | 24.223 | 0.4 (0.1) | 16.1 (1.0) | 214.52 | 0.88 | 8.2 | ||

| 20 | 24.297 | 0.6 (0.0) | 15.6 (0.9) | 215.47 | 0.56 | 7.6 | ||

| 35 | 24.382 | 7.8 (0.0) | 11 (0.3) | 215.83 | 0.53 | 6.9 | ||

| 40 | 25.323 | 8.4 (0.1) | 10.7 (0.4) | 232.52 | 0.56 | 6.2 | ||

| 50 | 25.798 | 12.1 | 9.8 (0.5) | 214.67 | 0.40 | 7.4 | ||

| 60 | 25.949 | 14.2 (0.2) | 9.6 (0.9) | 192.89 | ||||

| 70 | 26.114 | 16.3 (0.2) | 10.1 (0.2) | 166.82 | 0.24 | 7.5 | ||

| 80 | 26.265 | 18.5 (0.1) | 9.8 (0.5) | 141.99 | 0.19 | 6.5 | ||

| 90 | 26.446 | 21 (0.3) | 10.2 (0.2) | 57.76 | ||||

| 100 | 26.577 | 24.5 (0.1) | 11 (0.3) | 13.15 | *13.2 (2.3) | 38 | ||

| 110 | 26.704 | 19.4 (0.5) | 14.8 (0.1) | 1.63 | ||||

| 120 | 26.808 | 17.5 | 15.9 (0.1) | 0.97 | ||||

| 140 | 26.999 | 19.4 (1.4) | 13.8 | 0.67 | ||||

| 160 | 27.134 | 20 (0.5) | 12.7 (0.4) | 0.52 | ||||

| 180 | 27.26 | 23.4 (0.1) | 11.3 (0.1) | 0.47 | ||||

| 200 | 27.371 | 25 (0.01) | 11.1 (0.4) | 0.44 | *10.1 (1.0) | 38 | ||

| 225 | 27.524 | 27.5 (0.1) | 10.2 (0.1) | 0.40 | ||||

| 250 | 27.672 | 28.3 (0.2) | 10.1 (0.2) | 0.34 | 0.43 | 6.3 | ||

| 275 | 27.838 | 28.7 | 9.6 (0.2) | 0.35 | ||||

| 300 | 27.98 | 29.2 (0.4) | 9.7 (0.4) | 0.34 | ||||

| 325 | 28.153 | 30.9 (0.6) | 9.3 (0.4) | 0.31 | ||||

| 350 | 28.319 | 32.5 (0.9) | 9.0 (0.5) | 0.34 | ||||

| 375 | 28.47 | 34.2 | 8.1 (1.3) | 0.31 | ||||

| 400 | 28.664 | 36.2 | 0.32 |

Average δ15NPNsink flux values that include at least one sample that was acidified prior to isotopic analysis (to remove inorganic carbon) are indicated with an asterisk.

Because the ETSP has strong gradients in δ15NNO3+NO2 with depth in the upper thermocline (31, 33), we use water column profiles of density, concentration, and δ15NNO3+NO2, together with fluorescence (2010 cruise) or chlorophyll a concentration (2011 cruise), to select the δ15NNO3+NO2 end-member at each station (Fig. 1 and Table S1). The δ15N budgets were evaluated with three choices of the δ15NNO3+NO2 end-member: (i) the deep chlorophyll maximum, (ii) the depth of the floating sediment trap, and (iii) the shallowest δ15NNO3+NO2 minimum (Table S2). The lower concentration and elevated δ15NNO3+NO2 at the base of the deep chlorophyll maximum relative to depths immediately below (Fig. 1) indicates that assimilation has affected the δ15NNO3+NO2 at this depth and that the source of to the euphotic zone has a lower δ15N, arguing against this choice for the end-member (36). A similar argument can be made against assigning a δ15NNO3+NO2 source at the depth of the sediment trap. We argue that the shallowest δ15NNO3+NO2 minimum is most representative of the unaltered source of to the euphotic zone. Similar to the δ15NNfix end-member choice, lower δ15NNO3+NO2 end-member values will result in a smaller role for N2 fixation in supporting export production (Eq. 2). For comparison, the results of all three approaches are given in Table S2.

Table S2.

Evaluation of δ15N budgets with alternative δ15NNO3+NO2 end-members

| δ15N budget variables | Station | |||

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 13 | |

| 2010 δ15NPNsink | 11.7 ± 2.1‰ | 13.7‰ | 11.1 ± 0.1‰ | N/A |

| NO3−+NO2− source from trap depth | 100 m, 10% (32 ± 48) | 200 m, 0% (0) | 200 m, 0% (0 ± 0) | N/A |

| NO3−+NO2− source from base of chl max | 80 m, 19% (62 ± 43) | 200 m, 0% (0) | 200 m, 0% (0 ± 0) | N/A |

| NO3−+NO2− source from depth of shallowest NO3−+NO2− from δ15N minima | 150 m, 0% (0 ± 48) | 250 m, 0% (0) | 200 m, 0% (0 ± 0) | N/A |

| 2011 δ15NPNsink | 9.2 ± 1.4‰ | N/A | 7.9 ± 2.1‰ | 13.2 ± 2.3‰ |

| NO3−+NO2− source from trap depth | 100 m, 31% (36 ± 11) | N/A | 100 m, no NO3−+NO2− at 100 m | 100 m, 0% (0 ± 0) |

| NO3−+NO2− source from base of chl max | 140 m, 21% (24 ± 13) | N/A | 160 m, 21% (11 ± 10) | 90 m, 0% (0 ± 0) |

| NO3−+NO2− source from depth of shallowest NO3−+NO2− from δ15N minima | 140 m, 21% (24 ± 13) | N/A | 140 m, 20% (11 ± 10) | 60 m, 0% (0 ± 0) |

δ15N budget estimates of the fractional contribution of N2 fixation to export production (%) and corresponding N2 fixation rates in units of μmol N m−2 d−1 (in parentheses) with different source δ15NNO3+NO2 assumptions. Uncertainty represents ±1 SD of the δ15NPNsink measurement. Station 3 had no replicate δ15NPNsink measurements.

On the 2010 cruise, which took place during the austral summer from January to February 2010, the δ15N budgets did not detect N2 fixation at any of the three stations (Table 1 and Fig. S1). However, at Station 1, the SD associated with the δ15NPNsink measurement (11.7 ± 2.1‰) leads to relatively high uncertainty in the N2-fixation rate, 0 ± 48 µmol N m−2 d−1, leaving open the possibility that N2 fixation may have contributed up to 15% of export production (Table 1). At Station 3, no replicate measurements of the δ15NPNsink (13.7‰) were made, so no uncertainty in the N2-fixation rate of 0 µmol N m−2 d−1 could be estimated. At Station 5, the low SD associated with the δ15NPNsink measurement (11.1 ± 0.1‰) corresponds to no range in either the fractional contribution of N2 fixation to export production (0 ± 0%) or the N2-fixation rate (0 ± 0 µmol N m−2 d−1) (Table 1).

In March to April 2011, N2 fixation was detected in the δ15N budgets at Stations 1 and 5 (Table 1 and Fig. S1). The δ15N budget at Station 1 gave an N2-fixation rate of 24 ± 13 µmol N m−2 d−1, supporting 21 ± 10% of export production, which appears somewhat high and inconsistent with the lack of molecular evidence for diazotrophs at this station (21). Despite the relatively high SD of duplicate δ15NPNsink measurements (9.2 ± 1.4‰), the range of δ15NPNsink values within the uncertainty are lower than all of the δ15NNO3+NO2 shallower than 350 m (Fig. 1 and Table S1), indicating that N2 fixation is the likely source of the low-δ15N N required to balance the δ15N budget at Station 1. In addition, the δ15N mass balance-based N2-fixation rate is indistinguishable from the short-term N2-fixation rate measured at this station in 2011 (see Discussion below) (Table 1).

The δ15NPNsink at Station 5 on the 2011 cruise was 7.9 ± 2.1‰, lower than the δ15NNO3+NO2 throughout the upper 400 m, which is relatively constant with depth compared with other stations (Fig. 1). The δ15N budget at Station 5 yields N2-fixation rates of 11 ± 10 µmol N m−2 d−1, supporting 20 ± 19% of export production, although we note that the very low mass flux (0.05 mmol N m−2 d−1) (Table S3) likely contributes to the large uncertainty in δ15N budget calculations. The δ15NPNsink at Station 13 was 13.2 ± 2.3‰, which is higher than the δ15NNO3+NO2 at the shallowest δ15NNO3+NO2 minimum, 9.6 ± 0.9‰, and thus implies that N2 fixation does not support any export production at this station. However, a higher δ15NPNsink than the δ15NNO3+NO2 end-member indicates that another δ15NNO3+NO2 end-member may be more appropriate. For example, up to 16 ± 13% of export production at Station 13 could be supported by N2 fixation if 100% of the -fueled export production at this station originated between 100 and 150 m, with a maximum δ15NNO3+NO2 of 15.9‰, and where a secondary peak in chlorophyll a was observed (Fig. 1).

Table S3.

Summary of PNsink flux measurements

| Year and station | Trap depth, m | No. of traps deployed per depth (total no. of sample splits) | Length of trap deployment, h | PNsink flux, mmol N m−2 d−1 (±1 SD) | δ15NPNsink, ‰ vs. air (±1 SD) |

| 2010 | |||||

| 1 | 100 | 1 (2) | 35 | 0.317 | 11.7 (2.1) |

| 3 | 200 | 1 (1) | 37 | 0.027 | 13.7 |

| 5 | 200 | 1 (2) | 65 | 0.030 | 11.1 (0.1) |

| 2011 | |||||

| 1 | 100 | 2 (4) | 39 | 0.116 (0.05) | 9.2 (1.4) |

| 13 | 100 | 2 (4) | 38 | 0.153 (0.06) | 13.2 (2.3) |

| 5 | 100 | 2 (4) | 70 | 0.05 (0.02) | 7.9 (2.1) |

N2-Fixation Rates Derived from Productivity Metrics.

In the regions of the ETSP with -depleted surface waters, the δ15NPNsink flux is more similar to the δ15NNO3+NO2 in the upper thermocline than to the δ15NNfix end-member (Fig. 1), indicating that is the dominant source of new N fueling export production, consistent with results from other regions with -depleted surface waters (26–28). Although the composition of material captured in surface-tethered floating sediment traps is considered representative of the sinking flux, the magnitude of the export flux determined by sediment traps was lower than that recorded by other metrics of new and export production on these two cruises (37), as has been found previously (38). In cases where the δ15N budgets fail to detect N2 fixation, multiplying by alternative productivity metrics would not yield positive N2-fixation rates, and we expect that the results of the δ15N budgets that fail to detect N2 fixation at four of the six stations are robust (see Discussion below). However, when N2 fixation is detected in the δ15N budgets, multiplying the fraction of export production supported by N2 fixation (x in Eq. 1) by an underestimate of the export flux may consequently underestimate N2-fixation rates.

To address potential underestimation of N2-fixation rates attributable to undercollection of the export flux by the sediment traps, N2-fixation rates were also calculated using alternative metrics of new production (O2/Ar ratios, 14C uptake) and export production (234Th deficits) (Table S4). These alternative productivity metrics yielded higher rates of N2 fixation, with the highest N2-fixation rates at Station 1 resulting from multiplying the fractional importance of N2 fixation by the O2/Ar-based net community production (NCP) estimate (197 ± 59 µmol N m−2 d−1) and at Station 5 by the 234Th-deficit estimate of export production (100 ± 30 µmol N m−2 d−1). Multiplying the fractional contribution of N2 fixation to export production by these alternate productivity metrics provides a geochemically derived upper bound to regional N2-fixation rates, which, although lower than rates from the tropical North Atlantic (4), are comparable to the intermediate rates observed in the summer in the North Pacific gyre (39). Although this study did not extend to the regions of the Central Pacific, where N2 fixation was diagnosed by remote sensing studies (10), the prediction for the favorable surface ocean and concentrations and stoichiometry in the ETSP gyre to support the highest global N2-fixation fluxes (11) is not supported by δ15N budget calculations.

Table S4.

Rates of N2 fixation

| Year and station | Rnfix PNsink flux | Rnfix NCP (O2/Ar) | Rnfix 234Th | Rnfix 14C uptake |

| 2010 | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| 2011 | ||||

| 1 | 24 ± 13 | 197 ± 59 | 164 ± 45 | 111 |

| 5 | 11 ± 10 | 36 ± 77 | 100 ± 30 | 56 ± 17 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Values are in µmol N m−2 d−1, calculated by multiplying the fractional contribution of N2 fixation to export production from the δ15N budgets by different metrics of new and export production, including PNsink flux (Rnfix PNsink flux) (±1 SD), NCP from O2/Ar (Rnfix NCP (O2/Ar)) (±1 SD), 234Th deficits (Rnfix 234Th) (±1 SD), and 14C uptake rates (Rfnix 14C uptake) (±1 SD).

Discussion

Despite the δ15N budgets only detecting N2 fixation at Stations 1 and 5 on the 2011 cruise, N2 fixation was detected by short-term rate measurements at all stations on both cruises (Table 1). In 2011, the short-term N2-fixation rate at Station 1 (23 ± 24 µmol N m−2 d−1) is indistinguishable from the δ15N budget-based rate using sediment trap fluxes (24 ± 13 µmol N m−2 d−1), but lower than the other geochemical N2-fixation flux estimates, which range from 111 to 197 µmol N m−2 d−1 (Table S4). At Station 5, the short-term rate (86 ± 9 µmol N m−2 d−1) is higher than all but the 234Th-based N2-fixation rate estimate, 100 ± 30 µmol N m−2 d−1 (Table S4). To evaluate whether the short-term N2-fixation rates are consistent with the δ15N measurements, we (i) compare short-term rates of N2 fixation with the PNsink mass flux (Table S3) to evaluate what fraction of the PNsink flux the short-term rate represents (“fnfix”) and (ii) calculate what the δ15NPNsink would need to be for the δ15N budget to match the short-term rates (Table 1).

As described above, the δ15N budget-based N2-fixation rate is indistinguishable from the short-term incubation results at Station 1 in 2011, resulting in a predicted δ15NPNsink identical to what was measured (Table 1). At Station 13 in 2011, the short-term rates correspond to 39% of the export flux and would have resulted in a δ15NPNsink of 5.4‰, significantly lower than the measured δ15NPNsink of 13.2 ± 2.3‰ (Table 1). At the stations with lower organic matter fluxes, the short-term N2-fixation rates were several-fold larger than the PNsink fluxes (2010 cruise, Stations 3 and 5, and 2011 cruise Station 5), corresponding to predicted δ15NPNsink values of −1‰ (Table 1). We note that the discrepancy at Stations 3 and 5 on the 2010 cruise is exacerbated by the collection of the PNsink flux at 200 m; at all other stations, the PNsink flux was collected at 100 m (Table S3). At Station 5 in 2011, we suspect that the low mass flux at this ultraoligotrophic station (16), with the high SD for δ15NPNsink, contributes to the larger discrepancy between the short-term N2-fixation rate and the PNsink flux. We also note that the calculation of fnfix with the PNsink flux, as opposed to the other metrics of new and export production, represents an upper limit to the fractional importance of N2 fixation for supporting export production. However, together, these calculations suggest that the short-term N2-fixation rates should have been apparent in all of the δ15N budgets.

The larger discrepancy between the δ15N budget- and short-term incubation-based N2-fixation rates at stations with lower PNsink fluxes requires consideration of potential explanations. First, the N2 fixation measured in the short-term incubations may not have contributed to sinking particles if the diazotrophs did not sink and/or were grazed and not converted to fecal pellets before the sediment traps were recovered. However, this scenario might be expected to correspond to a stronger quantitative PCR-based signal of NifH than was observed at these stations (21) (see below). Additionally, analysis of δ15NPNsink collected at Station 5 in a deep (i.e., 3,660 m), moored sediment trap deployed from February 2010 to March 2011 shows that the δ15NPNsink does record the input of low-δ15N material, and thus N2 fixation’s geochemical signature is most pronounced, during the austral summer, when mass fluxes were lowest (22). Moreover, there is no evidence for preferential remineralization of low-δ15N material between the surface-tethered and 3,660-m traps (22), suggesting that whatever low-δ15N PNsink material was produced in surface waters was not rapidly remineralized to low-δ15N in the upper thermocline, as may occur in the subtropical North Pacific (28) and North Atlantic gyres (35), where N2-fixation rates are higher. Finally, euphotic zone DON concentration and δ15N at these stations (∼4.5–5.0 µM and 5.0 ± 0.5‰) were consistent with previous measurements from the North Pacific (40) and did not indicate that newly fixed N accumulated in the surface DON pool.

Another potential explanation for the discrepancy between the geochemical and short-term N2-fixation rates comes from recent work documenting the presence of 15N-labeled N-oxides and/or ammonium in several brands of 15N2-labeled gas (41), which could lead to an overestimate of N2-fixation rates using tracer techniques, especially when N2-fixation rates are low, as in the ETSP. Short-term N2-fixation rates in this study were determined using two (2010 cruise) or three (2011 cruise) different brands of labeled gas, including those identified as more and less contaminated (41), and showed largely comparable rates and many instances of N2-fixation rates at or near the limit of detection, arguing against this explanation as the cause of the discrepancy. Indeed, other work argues that short-term rates determined with gas may underestimate N2-fixation rates if gas is not properly equilibrated before incubation (42), which, if correct, would exacerbate the difference between short-term and geochemical N2-fixation rate estimates in this study.

The δ15N-budget– and short-term incubation-based N2-fixation rate estimates integrate over 24- to 70-h periods; in the context of the offset between the geochemical and short-term N2-fixation rates, it is useful to consider the results from a study of NifH gene expression on these same cruises, which should reflect diazotrophic activity over comparable time scales (21). Although diazotrophs could be detected, their abundance and activity in the ETSP was low compared with studies from other oligotrophic regions (21). Moreover, the heterotrophic diazotrophs that dominated the diaozotrophic community in the ETSP gyre typically have significantly lower per-cell N2-fixation rates than the cyanobacterial diazotrophs common where higher N2-fixation rates are found (4, 21, 39), and these low per-cell rates could not be reconciled with previously reported short-term N2-fixation rates in the ETSP gyre (21, 43). Thus, the molecular results from these cruises are consistent with the results of the δ15N budgets that fail to detect significant rates of N2 fixation at four of the six stations in the ETSP. The discrepancy between the NifH results and the short-term N2-fixation rates suggests two possibilities: that there are unrecognized diazotrophs contributing to the short-term N2-fixation rate measurements and/or that the short-term rates are artificially high and that actual N2-fixation rates are closer to the geochemical estimates, in particular at stations where the δ15N budgets did not detect N2 fixation. If the short-term rates are correct then the geochemical data implies that those rates do not persist for long periods of time, because the PNsink flux and δ15N required by the short-term rates are not consistent with the δ15N budgets (Table 1).

Finally, we expect that the higher proportion of export production supported by N2 fixation in 2011 compared with 2010 is related to the relative timing of the two cruises, with 2011 sampling later during the austral summer (March to April 2011 vs. January to February 2010). In particular, the results from a deep-moored sediment trap deployed at Station 5 from February 2010 to March 2011 records a minimum in δ15NPNsink between March to May 2010, when organic matter fluxes were also lowest (22), suggesting that the 2010 cruise may have preceded the peak regional significance of N2 fixation. The deep trap results also indicate that N2-fixation rates are unlikely to be significantly higher throughout the rest of the year, consistent with prior observations from adjacent waters sampled during the austral spring (16).

Summary

Here, we present an investigation of N2 fixation using biological and geochemical tools to evaluate the quantitative significance of N2 fixation in the ETSP. Although short-term N2-fixation rates integrated over the euphotic zone averaged 60 µmol N m−2 d−1, roughly half the rates measured in the North Pacific subtropical gyre (39), geochemical N2-fixation rates, together with a parallel analysis of NifH, suggest N2-fixation rates are lower still, from 11 to 24 µmol N m−2 d−1, when detected at all, and play a minimal role in supporting export production. When scaled to surface waters in the South Pacific with similar nutrient characteristics (i.e., < 1.0 µM and [] > 0.1 µM; 24 × 1012 m2), the δ15N budget-based N2-fixation rate of 10 µmol N m−2 d−1 corresponds to an annual flux of ∼1.2 Tg N y−1, whereas an intermediate short-term N2-fixation rate (or δ15N budget-based rate evaluated with an alternate productivity metric) of 75 µmol N m−2 d−1 corresponds to an annual flux of 9 Tg N y−1. Given that the moored trap δ15NPNsink data indicate that N2-fixation fluxes are unlikely to be significantly higher throughout the rest of the year (22), 9 Tg N y−1 can be considered an upper bound for regional N2-fixation fluxes. These rates are a small fraction of the 95 Tg N y−1 predicted for the whole Pacific basin from geochemical modeling studies (11), and also challenge the predictions (10, 11) that the highest global N2-fixation rates are found in the Central and Eastern tropical South Pacific. This work demonstrates that low and relatively high concentrations alone are insufficient to support significant N2-fixation fluxes, perhaps because of the scarcity of iron. The findings are also consistent with recent suggestions that higher N2-fixation rates might be found in the surface waters of the Southwest Pacific (18, 19), which maintains similarly favorable nutrient concentrations and ratios and receives relatively higher dust fluxes (15).

Materials and Methods

Water Column Sample Collection.

Samples were collected on the research vessel (R/V) Atlantis in January to February 2010, and the R/V Melville in March to April 2011 on a zonal transect along 20° S between 80° W and 100° W, with exact station locations and sample depths, nutrient concentrations, and isotopic compositions reported in Table S1. Water column samples were collected by Niskin bottles deployed on a rosette equipped with conductivity temperature depth (CTD), as well as dissolved oxygen Sea-Bird Electronics sensors. All samples were collected into acid-washed, sample-rinsed high-density polyethylene bottles, and samples from the upper 400 m passed a 0.2-µm filter before collection. All samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis on land.

Concentration and Isotopic Composition Analysis.

The concentration of was determined using chemiluminescent analysis (44) in a configuration with a detection limit of 0.05 µM and ±0.1 µM 1 SD. The δ15NNO3+NO2 was determined using the “denitrifier” method (45, 46) with modifications (47) on samples with > 0.3 µM (typically ≤0.2‰ 1 SD).

Sediment Trap Sample Collection and Analysis.

Sinking particulate material was collected using surface-tethered floating particle-interceptor traps (PIT) (48, 49) equipped with 12 polycarbonate cylinders. Floating sediment traps were deployed at 200 m at Stations 3 and 5 on the 2010 cruise; at all other stations traps were deployed at 100 m. Sediment trap samples were collected into a carbonate buffered brine solution and then split into replicate samples. In 2010, two splits were collected from each sediment trap, one of which was acidified to remove inorganic carbon. In 2011, two sediment traps were deployed at each station, each with an acidified and unacidified split (Table S3). In 2010, filtration through a 1-mm mesh removed “swimmers” from sediment trap material. On the 2011 cruise, swimmers were identified by dissecting microscopy and handpicked from sediment trap samples using sterilized micropipettors and forceps. Mass and isotopic fluxes were determined by combustion analysis of trap samples at the University of California Davis Stable Isotope Facility. The limit of detection for combustion analysis was 1.5 µmol of N. The mass-weighted average δ15N of acidified and nonacidified splits of trap material captured in the sediment traps is reported in Table 1 and Table S3.

15N2-Incubation Rate Measurements.

Short-term N2-fixation rate measurements incubated with gas from Sigma Aldrich (lot nos. SZ1670V and MBBB0968V) were carried out in triplicate in acid-washed, sample-rinsed, light-transparent 4-L polycarbonate bottles amended with 1.5 mL of 99 atom% and 1.5 mL of 0.5 M NaH13CO3. A third batch of 15N2 gas (Eurisotop) was used to make short-term rate measurements reported elsewhere (43). Incubations were performed with water collected from four depths within the euphotic zone under simulated in situ conditions of temperature and light and run for staggered periods (e.g., 0, 12, 24, and 48 h). Incubations were terminated by filtration of the 4-L sample onto a precombusted 25-mm Whatman glass fiber filter, which was then analyzed by mass spectrometry at the University of Southern California for δ15N.

The δ15N of suspended particulate N (PNsusp) (Table S1) averaged over the upper water column (∼150 m) was used as the time zero δ15N for determining the atom % excess for rate calculations. Trapezoidal integrations of discrete N2-fixation rate measurements extended down to 150 m, except on the 2010 cruise at Station 3 (180 m) and Station 5 (175 m). Limits of detection were 10–14 µg of N, and reproducibility (±1 SD) was ±0.3‰ for δ15N and ±0.1–0.2 µg for mass determinations.

Productivity Measurements.

234Th-based export fluxes were reported elsewhere (37, 50), and rates of O2/Ar-based NCP (reported in mmol C m−2 d−1) were determined from the stoichiometric equivalent of net oxygen production (NOP) [NCP = NOP/PQ, where PQ is a photosynthetic quotient (O2/C) taken here to have a value of 1.4 (51)]. NOP fluxes were calculated assuming steady-state O2 mass balance within the mixed layer: (52, 53), where kv is piston velocity (rate of gas exchange, determined as described in ref. 54), O2eq is the concentration of dissolved O2 in equilibrium with the atmosphere at the in situ temperature and pressure, and ΔO2Bio is the biological O2 supersaturation, determined as to factor out the effect of temperature/salinity variability on O2 solubility (52). The effect of bubble injection on dissolved O2/Ar is typically small enough to be neglected (55). Additional O2/Ar NCP methodological details are given in SI Materials and Methods. Finally, 14C uptake and chlorophyll a concentration methods used the Bermuda-Atlantic Time-Series Station protocols (56).

SI Materials and Methods

Mixed-layer dissolved O2/Ar ratios were measured continuously through the duration of both cruises as ratios of 32/40 masses with a quadrupole mass spectrometer (Prisma Plus 200; Pfeiffer) equipped with an equilibrator inlet (EIMS) following the methodology described in ref. 57. The science seawater intake was 4–5 m below the waterline of the R/V Atlantis (in 2010) and 3–4 m below the waterline of the R/V Melville (2011). Measurements were taken every 500 ms, and averaged over 2 min. The averaging time of the signal of gases supplied by the equilibrator is ∼15 min. At a ship speed of 5 kn, the EIMS O2/Ar ratio represents the signal averaged over ∼2.5 km. The 32/40 ion current ratio was calibrated every 6–12 h by admitting for 10 min ambient air into the mass spectrometer through a silica-fused capillary of dimensions identical to the equilibrator inlet capillary and interfaced with the inlet through a valve (Valco, HPLC Stream selector valve) (57). The NCP on station was calculated using O2/Ar values binned in 0.25° zonally (∼28 km at 20 °S latitude), with bins centered on the station locations.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the efforts and expertise of the scientists and crew aboard the R/V Atlantis and R/V Melville cruises. Particular recognition goes to T. Gunderson, M. Tiahlo, and N. Rollins. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Division of Ocean Sciences (NSF-OCE) Grants 0850905 and 0850801 (to A.N.K., D.G.C., K.L.C., and W.M.B.), 0961098 (to K.L.C.), and 0961207 (to W.M.B. and M.G.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been archived in the Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office (BCO-DMO) database (hdl.handle.net/1912/7227).

See Commentary on page 4246.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1515641113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sigman DM, Boyle EA. Glacial/interglacial variations in atmospheric carbon dioxide. Nature. 2000;407(6806):859–869. doi: 10.1038/35038000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falkowski PG. Evolution of the nitrogen cycle and its influence on the biological sequestration of CO2 in the ocean. Nature. 1997;387(6630):272–275. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore CM, et al. Large-scale distribution of Atlantic nitrogen fixation controlled by iron availability. Nat Geosci. 2009;2(12):867–871. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capone DG, et al. Nitrogen fixation by Trichodesmium spp.: An important source of new nitrogen to the tropical and subtropical North Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2005;19(2):GB2024. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruber N, Sarmiento JL. Global patterns of marine nitrogen fixation and denitrification. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1997;11(2):235–266. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandes JA, Devol AH, Yoshinari T, Jayakumar DA, Naqvi SWA. Isotopic composition of nitrate in the central Arabian Sea and eastern tropical North Pacific: A tracer for mixing and nitrogen cycles. Limnol Oceanogr. 1998;43(7):1680–1689. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandes JA, Devol AH. A global marine-fixed nitrogen isotopic budget: Implications for Holocene nitrogen cycling. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2002;16(4):1120. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsch C, Sigman DM, Thunell RC, Meckler AN, Haug GH. Isotopic constraints on glacial/interglacial changes in the oceanic nitrogen budget. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2004;18(4):GB4012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eugster O, Gruber N, Deutsch C, Jaccard SL, Payne MR. The dynamics of the marine nitrogen cycle across the last deglaciation. Paleoceanography. 2013;28(1):116–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westberry TK, Siegel DA. Spatial and temporal distribution of Trichodesmium blooms in the world’s oceans. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2006;20(4):GB4016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutsch C, Sarmiento JL, Sigman DM, Gruber N, Dunne JP. Spatial coupling of nitrogen inputs and losses in the ocean. Nature. 2007;445(7124):163–167. doi: 10.1038/nature05392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straub M, et al. Changes in North Atlantic nitrogen fixation controlled by ocean circulation. Nature. 2013;501(7466):200–203. doi: 10.1038/nature12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kustka AB, et al. Iron requirements for dinitrogen- and ammonium-supported growth in cultures of Trichodesmium (IMS 101): Comparison with nitrogen fixation rates and iron: carbon ratios of field populations. Limnol Oceanogr. 2003;48(5):1869–1884. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berman-Frank I, Cullen JT, Shaked Y, Sherrell RM, Falkowski PG. Iron availability, cellular iron quotas, and nitrogen fixation in Trichodesmium. Limnol Oceanogr. 2001;46(6):1249–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahowald NM, et al. Atmospheric iron deposition: Global distribution, variability, and human perturbations. Annu Rev Mar Sci. 2009;1:245–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnet S, et al. Nutrient limitation of primary productivity in the Southeast Pacific (BIOSOPE cruise) Biogeosciences. 2008;5(1):215–225. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutkiewicz S, Ward BA, Monteiro F, Follows MJ. Interconnection of nitrogen fixers and iron in the Pacific Ocean: Theory and numerical simulations. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2012;26(1):GB1012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber T, Deutsch C. Local versus basin-scale limitation of marine nitrogen fixation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(24):8741–8746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317193111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro FM, Dutkiewicz S, Follows MJ. Biogeographical controls on the marine nitrogen fixers. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2011;25(2):GB2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo YW, et al. Database of diazotrophs in global ocean: Abundance, biomass and nitrogen fixation rates. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2012;4(1):47–73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turk-Kubo KA, Karamchandani M, Capone DG, Zehr JP. The paradox of marine heterotrophic nitrogen fixation: Abundances of heterotrophic diazotrophs do not account for nitrogen fixation rates in the Eastern Tropical South Pacific. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16(10):3095–3114. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berelson WM, et al. Biogenic particle flux and benthic remineralization in The Eastern Tropical South Pacific. Deep Sea Res Part 1 Oceanogr Res Pap. 2015;99:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minagawa M, Wada E. Nitrogen Isotope Ratios of Red Tide Organisms in the East-China-Sea - a Characterization of Biological Nitrogen-Fixation. Mar Chem. 1986;19(3):245–259. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carpenter EJ, Harvey HR, Fry B, Capone DG. Biogeochemical tracers of the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap. 1997;44(1):27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigman DM, DiFiore PJ, Hain MP, Deutsch C, Karl DM. Sinking organic matter spreads the nitrogen isotope signal of pelagic denitrification in the North Pacific. Geophys Res Lett. 2009;36(8):L08605. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altabet MA. Variations in nitrogen isotopic composition between sinking and suspended particles - Implications for nitrogen cycling and particle transformation in the open ocean. Deep Sea Res A. 1988;35(4):535–554. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knapp AN, Sigman DM, Lipschultz F. N isotopic composition of dissolved organic nitrogen and nitrate at the Bermuda Atlantic time-series study site. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2005;19(1):GB1018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casciotti KL, Trull TW, Glover DM, Davies D. Constraints on nitrogen cycling at the subtropical North Pacific Station ALOHA from isotopic measurements of nitrate and particulate nitrogen. Deep Sea Res Part 2 Top Stud Oceanogr. 2008;55(14-15):1661–1672. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karsh KL, Trull TW, Lourey AJ, Sigman DM. Relationship of nitrogen isotope fractionation to phytoplankton size and iron availability during the Southern Ocean Iron RElease Experiment (SOIREE) Limnol Oceanogr. 2003;48(3):1058–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granger J, Sigman DM, Needoba JA, Harrison PJ. Coupled nitrogen and oxygen isotope fractionation of nitrate during assimilation by cultures of marine phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr. 2004;49(5):1763–1773. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casciotti KL, Buchwald C, McIlvin M. Implications of nitrate and nitrite isotopic measurements for the mechanisms of nitrogen cycling in the Peru oxygen deficient zone. Deep Sea Res Part 1 Oceanogr Res Pap. 2013;80:78–93. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu K-K, Kaplan IR. The Eastern Tropical Pacific as a source of 15N-enriched nitrate in seawater off Southern California. Limnol Oceanogr. 1989;34(5):820–830. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rafter PA, Sigman DM, Charles CD, Kaiser J, Haug GH. Subsurface tropical Pacific nitrogen isotopic composition of nitrate: Biogeochemical signals and their transport. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2012;26(1):GB1003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fawcett SE, Lomas M, Casey JR, Ward BB, Sigman DM. Assimilation of upwelled nitrate by small eukaryotes in the Sargasso Sea. Nat Geosci. 2011;4(10):717–722. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knapp AN, DiFiore PJ, Deutsch C, Sigman DM, Lipschultz F. Nitrate isotopic composition between Bermuda and Puerto Rico: Implications for N(2) fixation in the Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2008;22(3):GB3014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lourey MJ, Trull TW, Sigman DM. Sensitivity of delta N-15 of nitrate, surface suspended and deep sinking particulate nitrogen to seasonal nitrate depletion in the Southern Ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2003;17(3):1081. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haskell WZ, et al. Upwelling velocity and eddy diffusivity from 7Be measurements used to compare vertical nutrient flux to export POC flux in the Eastern Tropical South Pacific. Mar Chem. 2015;168:140–150. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emerson S. Annual net community production and the biological carbon flux in the ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2014;28(1):14–28. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sohm JA, Subramaniam A, Gunderson TE, Carpenter EJ, Capone DG. Nitrogen fixation by Trichodesmium spp. and unicellular diazotrophs in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2011;116(G3):G03002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knapp AN, Sigman DM, Lipschultz F, Kustka AB, Capone DG. Interbasin isotopic correspondence between upper-ocean bulk DON and subsurface nitrate and its implications for marine nitrogen cycling. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2011;25(4):GB4004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dabundo R, et al. The contamination of commercial 15N2 gas stocks with 15N-labeled nitrate and ammonium and consequences for nitrogen fixation measurements. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohr W, Grosskopf T, Wallace DWR, LaRoche J. Methodological underestimation of oceanic nitrogen fixation rates. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dekaezemacker J, et al. Evidence of active dinitrogen fixation in surface waters of the eastern tropical South Pacific during El Niño and La Niña events and evaluation of its potential nutrient controls. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2013;27(3):768–779. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braman RS, Hendrix SA. Nanogram nitrite and nitrate determination in environmental and biological materials by vanadium (III) reduction with chemiluminescence detection. Anal Chem. 1989;61(24):2715–2718. doi: 10.1021/ac00199a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sigman DM, et al. A bacterial method for the nitrogen isotopic analysis of nitrate in seawater and freshwater. Anal Chem. 2001;73(17):4145–4153. doi: 10.1021/ac010088e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casciotti KL, Sigman DM, Hastings MG, Böhlke JK, Hilkert A. Measurement of the oxygen isotopic composition of nitrate in seawater and freshwater using the denitrifier method. Anal Chem. 2002;74(19):4905–4912. doi: 10.1021/ac020113w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McIlvin MR, Casciotti KL. Technical updates to the bacterial method for nitrate isotopic analyses. Anal Chem. 2011;83(5):1850–1856. doi: 10.1021/ac1028984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soutar A, Kling SA, Crill PA, Duffrin E. Monitoring marine-environment through sedimentation. Nature. 1977;266(5598):136–139. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knauer GA, Martin JH, Bruland KW. Fluxes of particulate carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in the upper water column of the northeast Pacific. Deep Sea Res A. 1979;26(1):97–108. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haskell WZ, Berelson WM, Hammond DE, Capone DG. Particle sinking dynamics and POC fluxes in the Eastern Tropical South Pacific based on 234Th budgets and sediment trap deployments. Deep Sea Res Part 1 Oceanogr Res Pap. 2013;81:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laws EA. Photosynthetic quotients, new production and net community production in the open ocean. Deep Sea Res A. 1991;38(1):143–167. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emerson S, Quay P, Stump C, Wilbur D, Knox M. O2, Ar, N2, and 222Rn in surface waters of the subarctic Ocean: Net biological O2 production. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1991;5(1):49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bender M, et al. A comparison of 4 methods for determining planktonic community production. Limnol Oceanogr. 1987;32(5):1085–1098. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yeung LY, et al. Upper-ocean gas dynamics from radon profiles in the Eastern Tropical South Pacific. Deep Sea Res Part 1 Oceanogr Res Pap. 2015;99:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanley RHR, Kirkpatrick JB, Cassar N, Barnett BA, Bender ML. Net community production and gross primary production rates in the western equatorial Pacific. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2010;24(4):GB4001. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lorenzen S, Tuel M. Bermuda Atlantic Time-Series Study. Bermuda Biological Station for Research; St. George, Bermuda: 1989. Primary production. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cassar N, et al. Continuous high-frequency dissolved O2/Ar measurements by equilibrator inlet mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81(5):1855–1864. doi: 10.1021/ac802300u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]