Significance

The transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) plays a vital role in cellular immune, stress, and proliferative responses by regulating genes. To maintain correct execution of the genetic program and to prevent pathologies (e.g., chronic inflammation), the activation of NF-κB has to be transient and precisely controlled. We describe a unique inhibitory mechanism that mediates NF-κB–dependent regulation of inflammation-associated genes and uses arginine methylation of the RelA subunit of NF-κB by protein arginine methyltransferase 1. This modification reduces the DNA-binding affinity of RelA, altering the recruitment to gene promoters and the transcriptional potency of NF-κB. This may be developed into an approach to inhibit the pathological functions of NF-κB.

Keywords: arginine methylation, genes, TNFα, NF-κB

Abstract

Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) is an inducible transcription factor that plays critical roles in immune and stress responses and is often implicated in pathologies, including chronic inflammation and cancer. Although much has been learned about NF-κB–activating pathways, the specific repression of NF-κB is far less well understood. Here we identified the type I protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) as a restrictive factor controlling TNFα-induced activation of NF-κB. PRMT1 forms a cellular complex with NF-κB through direct interaction with the Rel homology domain of RelA. We demonstrate that PRMT1 methylates RelA at evolutionary conserved R30, located in the DNA-binding L1 loop, which is a critical residue required for DNA binding. Asymmetric R30 dimethylation inhibits the binding of RelA to DNA and represses NF-κB target genes in response to TNFα. Molecular dynamics simulations of the DNA-bound RelA:p50 predicted structural changes in RelA caused by R30 methylation or a mutation that interferes with the stability of the DNA–NF-κB complex. Our findings provide evidence for the asymmetric arginine dimethylation of RelA and unveil a unique mechanism controlling TNFα/NF-κB signaling.

Immune responses are often associated with inflammation that evolved in higher organisms as a defense mechanism to protect them from infection and tissue injury (1); however, inappropriate control of inflammatory responses may give rise to chronic inflammation that leads to various pathologies, including cancer (2). Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) is a major proinflammatory cytokine that controls systemic inflammation and the acute-phase reaction. TNFα activates a rapid transcription of genes regulating inflammation, primarily through activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) (3). Some of these genes act to suppress TNFα-induced apoptosis, whereas others promote inflammation (4). Thus, the outcome of inflammatory response downstream of TNFα signaling is largely dependent on the genetic program regulated by NF-κB.

NF-κB is a family of transcription factors formed by homodimerization or heterodimerization of related Rel proteins, including RelA, p105/p50, p100/p52, c-Rel, and RelB (5). Among these, RelA- and c-Rel–containing NF-κB dimers are engaged mainly downstream of the canonical signaling induced by TNFα. Treatment of cells with TNFα leads to activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, resulting in phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB proteins, which normally restrain inactive NF-κB in the cytoplasm (6). This promotes the accumulation of NF-κB in the nucleus, where it binds to κB DNA consensus sequences and activates target genes. Although NF-κB is regulated by complex formation with IκBs (7) and controlled nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling (8, 9), additional mechanisms are needed to ensure the proper specificity, magnitude, and timing of NF-κB responses. Those include the interactions of NF-κB with various cofactors and heterologous DNA-binding proteins and various posttranslational modifications of Rel proteins and histones surrounding NF-κB target genes (10, 11).

Over the past decade, multiple covalent modifications of the transactivating RelA subunit, including phosphorylation, acetylation, O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamination, sumoylation, nitrosylation, and degradation-promoting ubiquitination, have been described to regulate transcriptional activity, DNA binding, and target gene specificity of NF-κB (11). Recent work of several laboratories has identified methylation as another regulatory RelA modification that controls gene expression downstream of TNFα and IL-1β signaling. Several histone lysine methyltransferases, including SET7/9, SETD6, and NSD1, have been shown to both positively and negatively regulate NF-κB through direct monomethylation or dimethylation of distinct lysine residues in RelA (12–15). Recent studies also have shown that RelA is methylated by the type II protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5), which catalyzes the synthesis of ω-NG-monomethylarginine (MMA) and symmetric ω-NG,N′G-dimethylarginine (SDMA) (16, 17).

The molecular aspects and functional consequences of RelA lysine methylation have been studied extensively, whereas the regulation of NF-κB by arginine methylation is just beginning to emerge. In addition to PRMT5, several type I PRMTs, including PRMT1, PRMT2, PRMT4, and PRMT6, have been shown to coregulate NF-κB target genes (18–22); however, it remains unclear whether Rel proteins are also modified by type I PRMTs that methylate arginines asymmetrically, thereby leading to the formation of asymmetric ω-NG,NG-dimethylarginine (ADMA).

Accumulating data indicate that both PRMT5 and a group of asymmetric type I PRMTs, in particular PRMT1, frequently share common recognition sequences and can compete for the same arginine residues. The interplay between type I and II arginine methylation is well documented in transcriptional regulation. Asymmetric dimethylation of histone H4R3 by PRMT1 has been linked to the activation of genes (23), whereas symmetric dimethylation of H4R3 by PRMT5 is associated with repression (24). In addition to histones, both types of arginine methylation regulate other proteins involved in the initiation and elongation steps of transcription. Similar to histone H4R3 methylation, PRMT1 and PRMT5 antagonize each other and differentially regulate E2F-1 by producing asymmetrically and symmetrically dimethylated forms of E2F-1, respectively (25). Transcriptional elongation factor SPT5 also can be methylated at a single arginine residue in its RNApol II-binding domain by PRMT1 and PRMT5, resulting in inhibition of the elongation-promoting activity of SPT5 at the promoters of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and NF-κB inhibitor α (NFKBIA) genes (26).

Given that type I and II PRMTs often share common substrates, it is possible that, along with providing symmetric dimethylation, methyl groups can modify RelA asymmetrically as a part of complex and context-specific NF-κB regulation. Here we present evidence that the RelA subunit of NF-κB is a direct target of PRMT1. We demonstrate that PRMT1 forms a cellular complex with RelA and asymmetrically dimethylates the conserved R30 residue in the RelA DNA-binding L1 loop. The asymmetric dimethylation of RelA by PRMT1 is enhanced after prolonged treatment of cells with TNFα and, in contrast to the symmetric modification (16, 17), negatively regulates the DNA binding and transcriptional activity of RelA. We also find that down-regulation of PRMT1 enhances the expression of NF-κB target genes after TNFα stimulation by facilitating RelA recruitment to specific promoters. Taken together, our findings reveal a previously unidentified posttranslational modification of RelA, namely asymmetric arginine dimethylation, which regulates NF-κB in response to TNFα.

Results

The Rel Homology Domain of RelA Interacts with PRMT1 and Is a Substrate for Arginine Methylation.

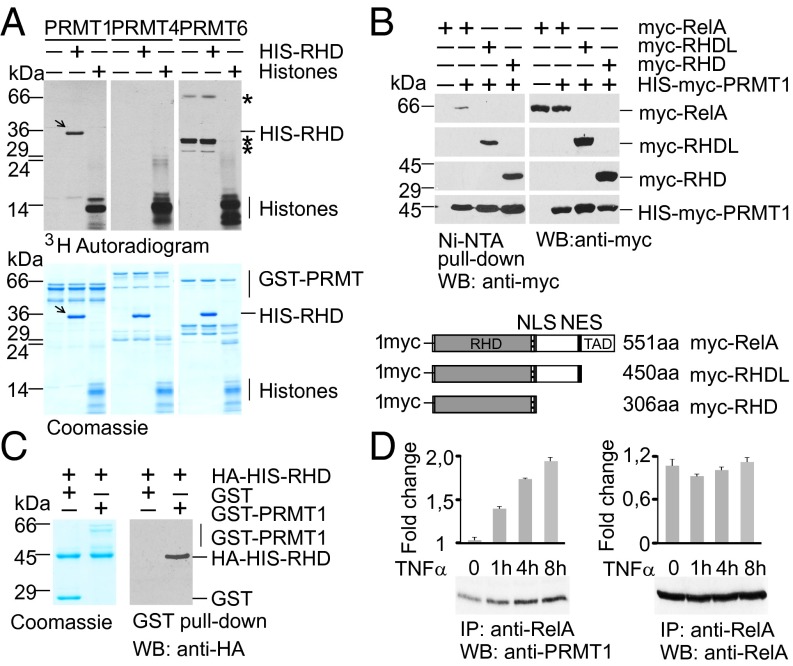

Given that type I PRMTs are known to control NF-κB target genes (18–22), we investigated whether Rel proteins are modified by asymmetric arginine dimethylation. We tested PRMT1, PRMT4, and PRMT6, all of which are present in the nucleus and modify histones, for their ability to methylate the RelA subunit of NF-κB. The bacterially expressed His-Rel homology domain (RHD) of RelA (amino acids 1–306) was incubated with affinity-purified GST-PRMTs in the presence of 3H-S-adenosine-methionine (3H-SAM) as a donor of methyl groups (Fig. 1A). Calf thymus core histones were used to control PRMT activities. Among the PRMTs tested, only PRMT1 was able to specifically methylate the RHD of RelA in vitro.

Fig. 1.

PRMT1 interacts with the RelA subunit of NF-κB and methylates the RHD of RelA. (A) Recombinant PRMTs were incubated with histones or His-RelA (amino acids 1–306) in the presence of 3H-SAM, resolved by SDS/PAGE, and analyzed by autoradiography. Arrows indicate methylated RelA; asterisks represent automethylated PRMT6 peptides. (B) PRMT1 forms a complex with RelA in vivo. (Upper) Full-length and deletion variants of RelA were expressed in HEK 293T cells and copurified with ectopic His-PRMT1. (Lower) The variants of RelA are shown schematically. The RHD, TAD, and nuclear import (NLS) and export (NES) signals are indicated. (C) PRMT1 physically binds to the RHD of RelA. In vitro GST pull-down assays were performed using the HA-His-RHD with GST or GST-PRMT1 purified from bacteria. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. (D) HEK 293T cells were stimulated with 20 ng/mL of TNFα for the indicated times. Endogenous RelA complexes were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates and analyzed for the presence of PRMT1. Intensities of the immunoblot signals were quantified using ImageJ 1.49.

To obtain further evidence that RelA is targeted by PRMT1, we tested the associations between these proteins in vivo and in vitro. For this, HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with myc-RelA and His-myc-PRMT1 or control expression vectors, and PRMT1-specific protein complexes were purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose. As shown in Fig. 1B, RelA was specifically copurified with PRMT1, suggesting complex formation between these proteins in vivo. To assess which region in RelA interacts with PRMT1, we used C-terminal deletion mutants of RelA lacking the linker region and/or the transactivation domain (TAD) (Fig. 1B, Lower). Analysis of RelA mutants revealed that the deletion of linker and/or TAD did not impair binding to PRMT1-specific cellular complexes. Consistent with these results, bacterially expressed GST-PRMT1 interacted with the RHD of RelA in an in vitro GST pull-down assay (Fig. 1C). This indicates a direct interaction between the N-terminal RHD of RelA and PRMT1. The association between RelA and PRMT1 was detected in unstimulated cells, and the level of coimmunoprecipitated PRMT1 was increased on TNFα treatment (Fig. 1D). We conclude that this interaction is dynamic and might be regulated in a stimulus-dependent manner.

PRMT1 Methylates RelA at Evolutionary Conserved R30.

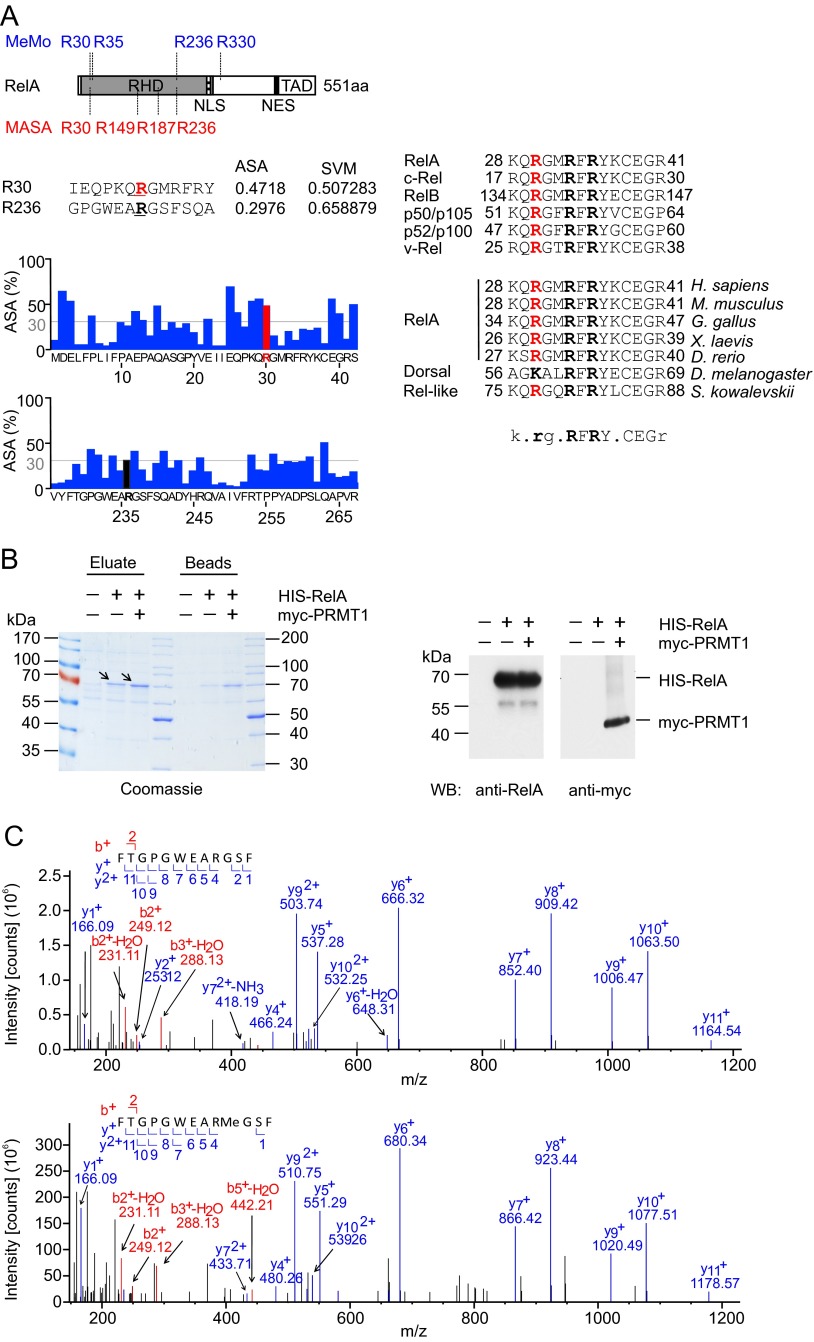

To identify putative PRMT1 consensus sites, we analyzed the protein sequence of RelA with two web-based bioinformatics tools, MeMo 2.0 (27) and MASA 1.0 (28). MeMo uses a support vector machine (SVM) algorithm, whereas MASA combines SVM with structural characteristics of proteins to identify methylation sites. In silico analysis of the RelA sequence by MeMo revealed four putative consensus sites for arginine methylation (Fig. S1A, Left): R30, R35, and R236, located within the RHD of RelA, and R330, located outside of the RHD. Analysis with MASA identified R30, R149, R187, and R236 as potential modification sites with an SVM score above the threshold of 0.5 (Fig. S1A, Left). To increase the stringency of prediction, we excluded R35, R149, R187, and R330, because they were confirmed by only one of these programs. Further analysis using MASA also excluded R236, because it was characterized by a low value of the solvent-accessible surface area surrounding the predicted methylation site (Fig. S1A, Left). Thus, the use of different prediction algorithms identified R30 as a prominent residue potentially methylated in RelA.

Fig. S1.

Identification of methylation sites in RelA. (A) In silico analysis of putative methylation sites in RelA by MeMo 2.0 and MASA 1.0. (Left) Schematic representation of the RelA protein as described in Fig. 1B. (Upper) Positions of predicted methylation sites. (Lower) Analysis of solvent-accessible surface areas surrounding R30 and R236 residues performed using MASA 1.0. (Right) Alignment of protein sequences adjacent to R30 among different species and NF-κB family members. (B) His-RelA (arrows) was purified from control, His-RelA–expressing, or His-RelA and myc-PRMT1–expressing HEK 293T cells using Ni-NTA beads. Proteins were eluted from beads with 0.1% TFA/50% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, and pH was neutralized by adding triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer. A 1/6th part of the eluate was analyzed by SDS/PAGE (Left), and a 1/20th part was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-RelA(C20) antibodies (Right). The expression of myc-PRMT1 was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-myc 9E10 antibody. (C) MS/MS spectra of the nonmethylated (Upper) and monomethylated (Lower) peptide 228FTGPGWEARGSF239 containing R236.

Interestingly, the same residue has been identified previously in vivo symmetrically dimethylated by PRMT5 (16), further supporting our in silico prediction. This prompted us to investigate whether R30 resides within a more general methylation consensus sequence that could be methylated by PRMT1. Sequence alignment revealed that R30 of RelA is highly conserved throughout all Rel proteins, including the viral oncoprotein v-Rel (Fig. S1A, Right). Moreover, the R30 residue and its surrounding RxxRxRxxC motif are evolutionarily conserved in species ranging from the hemichordate worm Saccoglossus kowalevskii to Homo sapiens. Dorsal, the Drosophila homolog of RelA, also appears to have a putative methylation site (albeit a lysine) in the same position.

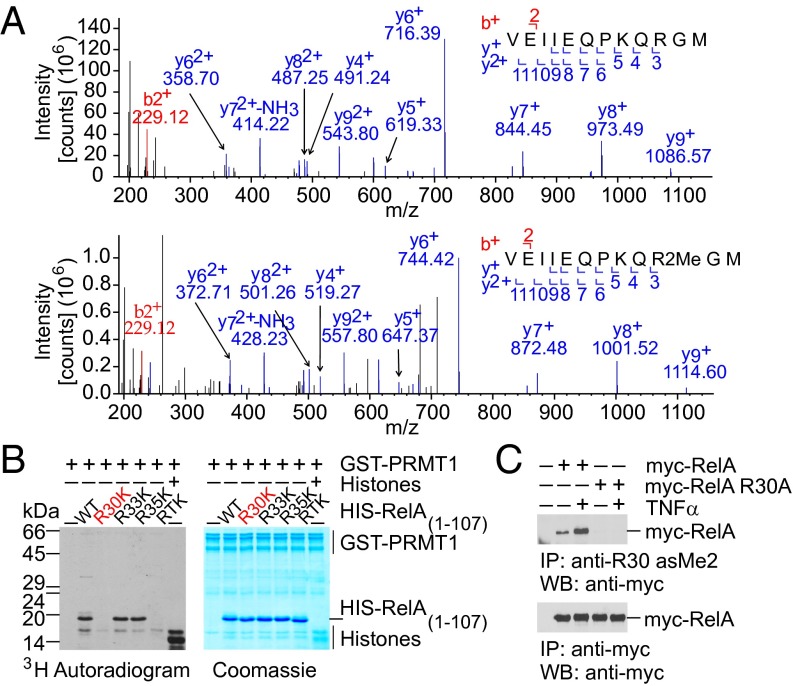

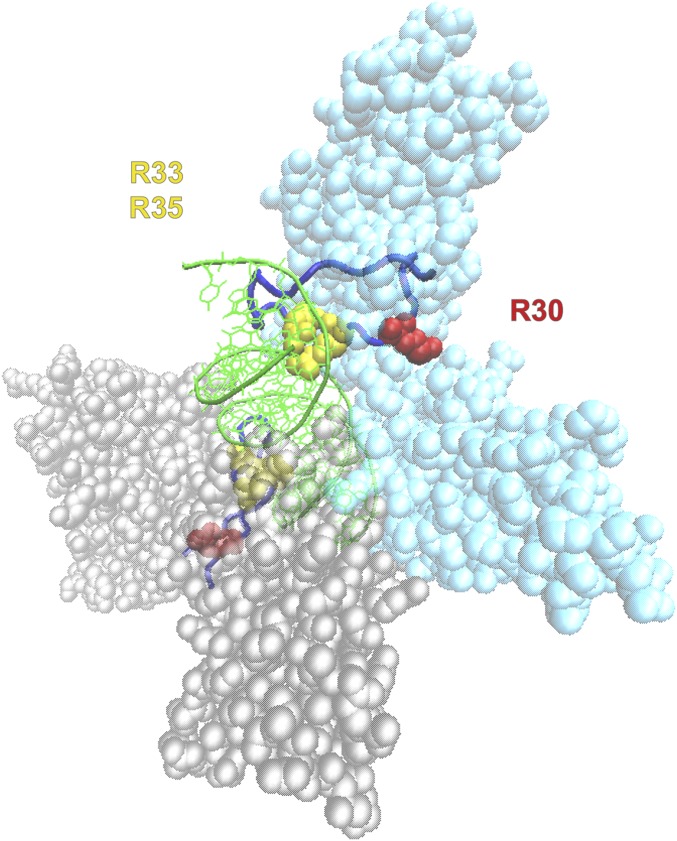

We next performed LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis to identify PRMT1-specific methylation sites in RelA ex vivo. His-RelA was ectopically expressed alone or coexpressed with PRMT1 in HEK 293T cells followed by affinity purification using Ni-NTA agarose (Fig. S1B). MS analysis revealed a dimethylation-specific 28-Da mass shift detected at R30 in the 21VEIIEQPKQRGM32 peptide (Fig. 2A). To further verify the R30 methylation by PRMT1, each or all arginine residues present in RxxRxRxxC motif were substituted with lysine. A single point mutation at R30 (R30K) or a triple mutation at R30, R33, and R35 (RTK) completely abolished the His-RelA peptide (amino acids 1–107) methylation by PRMT1 (Fig. 2B), whereas single-substitution R33K or R35K had no detectable effect. Analysis of the crystal structure of RelA:p50 dimer bound to the κB DNA sequence of the IFNβ promoter (29) confirmed that R30 is located in the exposed DNA-binding L1 loop region of RelA, whereas R33 and R35 are less sterically accessible for methylation (Fig. S2). Similarly, methylation of the RG motif in the context of the RGxRxR sequence by PRMT1 has been shown for dishevelled 3 (Dvl3) (30).

Fig. 2.

PRMT1 methylates RelA at R30 located within the DNA-binding L1 loop of the RHD. (A) Human RelA was analyzed by MS for the presence of methylarginine residues. Shown are MS/MS spectra of the nonmethylated (Upper) and dimethylated (Lower) peptide 21VEIIEQPKQRGM32 containing R30. (B) In vitro methylation assay with GST-PRMT1 and wild-type or mutant RelA (amino acids 1–107) in the presence of 3H-SAM. The RTK mutant harbors substitutions of R30, R33, and R35 to lysine. (C) TNFα stimulates RelA methylation at R30 in vivo. HEK 293T cells expressing myc-RelA or myc-RelA R30A were stimulated with TNFα for 8 h, and RelA methylation was analyzed by immunoprecipitation with anti-R30 asMe2, followed by immunoblotting using anti–c-myc (9E10) antibodies.

Fig. S2.

The 3D structure of the IFNβ-κB-NF-κB (RelA:p50) complex (29). The nucleotide backbone of IFNβ-κB DNA (green) is shown in a tube model, with nucleotide side chains presented as lines. The RelA (cyan) and p50 (gray) subunits of NF-κB are shown in a space-filling model. R30, R33, and R35 in RelA and the corresponding conserved R53, R56, and R58 in p50 are highlighted in yellow and red, respectively. DNA-contacting loops (L1) of RelA and p50 are presented in a tube model and are shown in blue.

To investigate R30 methylation in RelA in vivo, we generated antibodies that specifically recognize asymmetric dimethylation at R30 (Fig. S3 A and B). As shown in Fig. 2C, the methylation-specific antibodies immunoprecipitated ectopically expressed wild-type RelA protein but not its mutated R30A version, indicating asymmetric dimethylation of R30 in vivo as well. Furthermore, in vivo experiments revealed that R30 methylation could be stimulated by TNFα, suggesting a possible regulatory role of this modification in agonist-induced NF-κB responses.

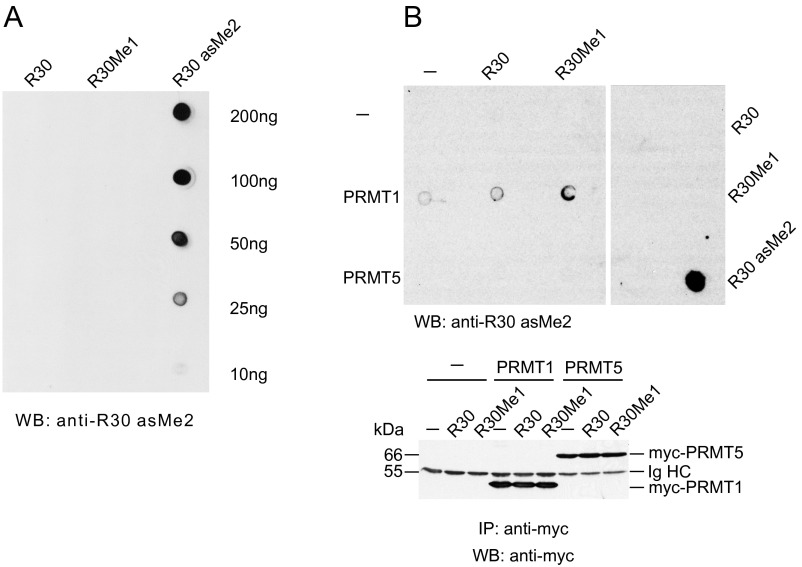

Fig. S3.

Validation of anti-R30 asMe2 antibodies. (A) Dot-blot analysis of unmodified, monomethylated, or asymmetric dimethylated RelA peptides (amino acids 26–34) using anti-R30 asMe2 antibodies. (B) Unmodified or monomethylated RelA peptides (amino acids 26–34) were left unprocessed or were methylated by PRMT1 or PRMT5 in vitro and analyzed as above. The same amounts of unmodified, monomethylated, or asymmetrically dimethylated RelA peptides served as negative or positive controls, respectively (Right). Distinct parts of the same nitrocellulose membrane are separated by a white space.

PRMT1-Targeted R30 Is Critical for the DNA-Binding and Transactivation Function of RelA.

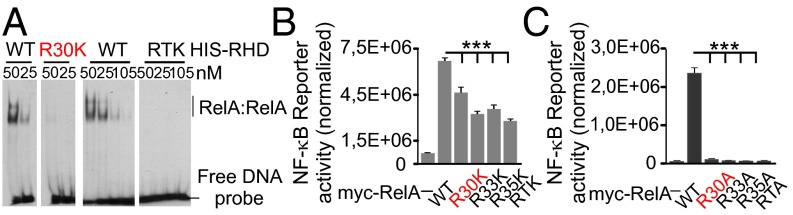

The N-terminal RxxRxRxxC motif of RelA is a functional element of the DNA-binding L1 loop that provides a DNA sugar-phosphate backbone and base-specific contacts (31, 32). Although R30 does not directly contact DNA (Fig. S2), it is located within the RxxRxRxxC motif of the L1 loop in close proximity to the DNA-contacting R33 and R35. This prompted us to investigate whether PRMT1-targeted R30 is important for the function of the L1 loop. For this, the wild-type RHDs of RelA, R30K, and RTK mutants were purified from Escherichia coli and analyzed for their ability to bind DNA by an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and a fluorescence-based thermal-shift assay. Although the R30K substitution did not change the positive charge at this position, the mutation decreased the thermal stability of the RHD and inhibited DNA binding substantially (Fig. 3A and Fig. S4). Inhibition was also observed for the RTK mutant, in which R30 and two other critical DNA-binding residues were mutated.

Fig. 3.

R30 mutations inhibit the DNA-binding and reporter activity of RelA. (A) EMSA of wild-type and mutated RelA proteins using the κB consensus oligonucleotide. Distinct parts of the same gel are separated by white spaces. (B and C) HEK 293T cells were transfected with 2×(κB)-luciferase reporter and wild-type or mutated myc-RelA constructs. The luciferase activity is presented as normalized mean values ± SD of triplicates. RTA and RTK possess substitutions of R30, R33, and R35 to alanine and lysine, respectively.

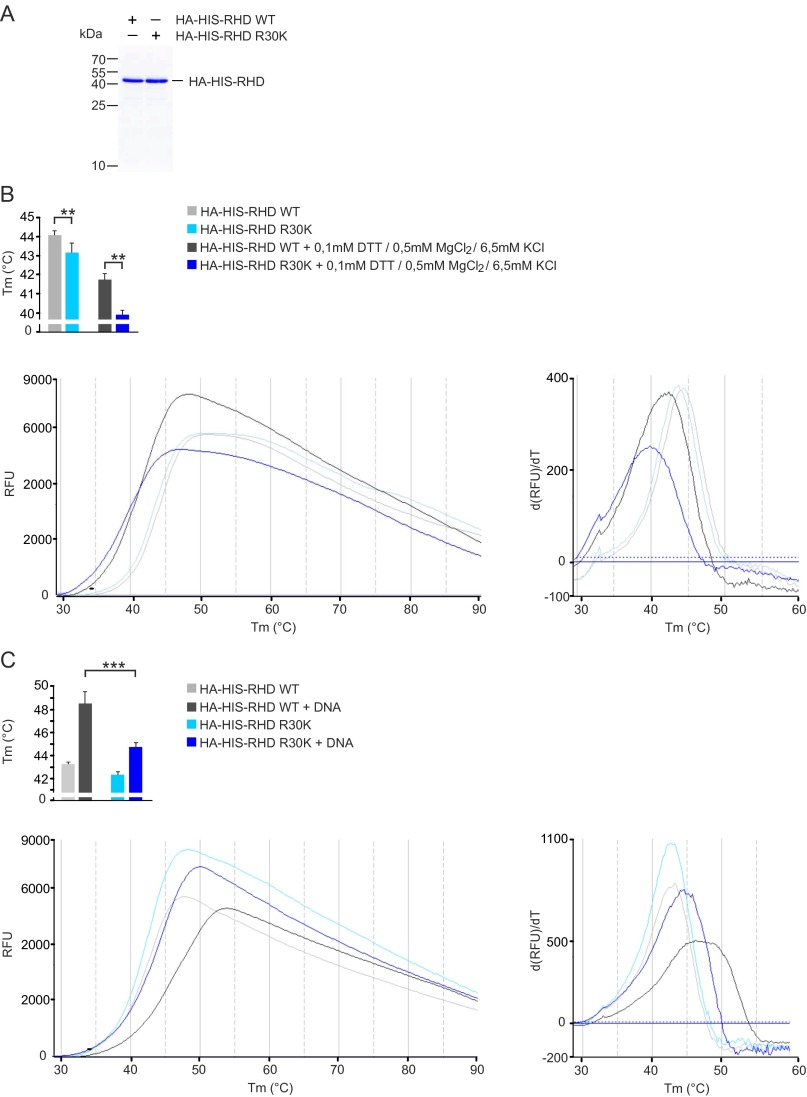

Fig. S4.

Fluorescence-based thermal-shift assays. (A) 15% (wt/vol) SDS/PAGE of purified recombinant wild-type and R30K mutated HA-His-RHD (amino acids 1–306) of RelA used for thermal-shift assays. (B, Left) Representative unfolding curves of HA-His-RHD WT and HA-His-RHD R30K over a temperature (T) range of 30–90 °C obtained under standard conditions (light gray and light blue) or in the presence of EMSA buffer components (dark gray and dark blue). (Right) Positive derivative [d(RFU)/dT] curves are shown. RFU, relative fluorescence unit. Midpoint temperatures of the protein-unfolding transition (Tm) are presented as bars. Values are mean ± SD of at least three independent measurements. (C) DNA-binding–dependent thermal stabilization of HA-His-RHD WT and HA-His-RHD R30K proteins in the thermal-shift assay. Results are presented as above.

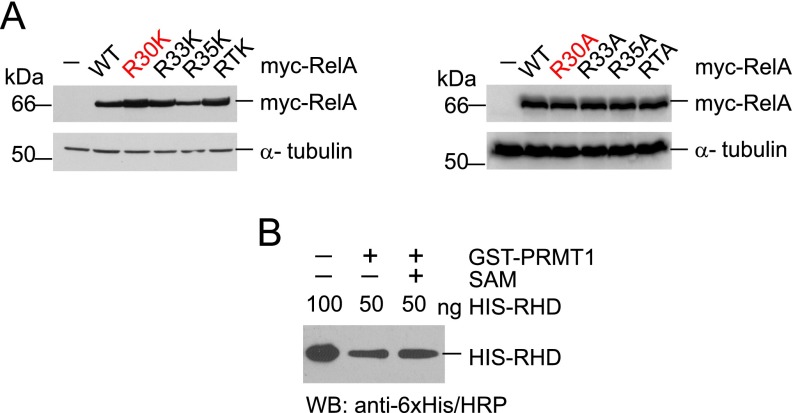

Given that DNA binding is important for the transcriptional activity of RelA, we assumed that the R30 mutation might affect RelA-dependent transcription. To test this, the mutant RelA proteins R30K, R33K, R35K, or RTK or similar mutants possessing R-to-A substitutions were transiently expressed in HEK 293T cells and analyzed by luciferase assays (Fig. 3 B and C and Fig. S5A). Consistent with our EMSA results, the R30K mutation decreased RelA transcriptional activity compared with the wild-type protein (Fig. 3B). A similar suppression of RelA was caused by R33K, R35K, and RTK mutations. Moreover, substitution of R30 to alanine, which is associated with the loss of a positive charge, resulted in almost complete inhibition of RelA reporter activity (Fig. 3C). Comparable inhibition of the reporter was observed for the R33A, R35A, and RTA mutants as well. These data reveal that, similar to R33 and R35, the R30 residue is structurally and functionally important for the RelA DNA binding and transcriptional activity.

Fig. S5.

(A) Immunoblot analyses of ectopically expressed RelA mutants using anti–c-myc (9E10) antibody. The loading was controlled by anti–α-tubulin antibody. (B) Comparison of nonmethylated and methylated proteins used in the EMSA. Comparable amounts of nonmethylated and methylated proteins were verified by immunoblotting with anti-6×His/HRP antibody.

Methylation of RelA by PRMT1 Represses DNA Binding and Reporter Activity of NF-κB.

Because R30 is critical for the L1 loop function, we studied whether RelA methylation by PRMT1 affects the binding of NF-κB to DNA and transcriptional activity. For this, purified His-RHD of RelA was incubated with recombinant GST-PRMT1 in the presence or absence of SAM. Both samples were verified for equal amounts of RelA protein and then tested for DNA binding by EMSA (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5B). The analysis showed that methylated RelA had lower affinity to a κB consensus oligonucleotide compared with that of nonmethylated protein.

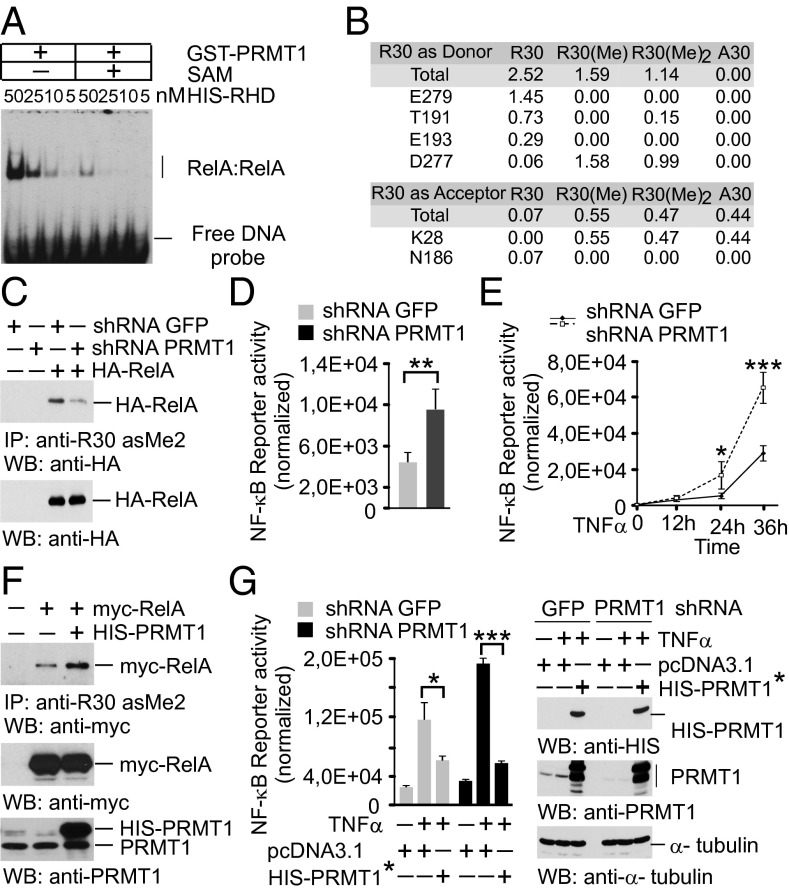

Fig. 4.

RelA methylation by PRMT1 inhibits the DNA-binding and transcriptional activity of NF-κB. (A) EMSA with nonmethylated and in vitro methylated RelA was performed as shown in Fig. 3A. (B) Hydrogen-bonding occupancy of nonmethylated, monomethylated, and asymmetrically dimethylated R30 and A30 in molecular dynamics simulations. (C) HEK 293T cells expressing shRNAs were transfected with control vector or an HA-RelA construct. RelA methylation was analyzed as in Fig. 2C, followed by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody. (D) Control and PRMT1 knockdown HEK 293T cells were transfected with 2×(κB)-luciferase reporter. Luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates and normalized to protein content. (E) Cells were transfected with the NF-κB reporter and stimulated with 20 ng/mL TNFα for 40 min. Luciferase activity was measured at the indicated time points. (F) HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with myc-RelA and His-PRMT1–expressing plasmids. R30 methylation was analyzed as above. (G) Cells were transfected with control or shRNA-resistant His-PRMT1* constructs. (Left) Luciferase assays were performed as described in E. (Right) The expression of His-PRMT1 was controlled by immunoblotting. Values are means ± SD of triplicates. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To obtain more molecular details on how the R30 methylation affects RelA DNA binding, we performed molecular dynamics simulations of the DNA-bound RelA:p50 dimer. We found that monomethylation and asymmetric R30 dimethylation preserved the DNA-protein complex over 100 ns but altered local hydrogen bonding (Fig. 4B); for instance, a loss of free H-bond donor functions was observed for the R30 amino acid side chain on monomethylation and asymmetric dimethylation. This predicted a reduction in H-bond formation with acceptor residues, such as E279, T191, and E193. In contrast, H bonding of R30 with D277 and K28 residues was enhanced on methylation. The replacement of R30 by alanine, a mutation inhibiting RelA (Fig. 3C), was also found to affect H bonding similar to that observed for methylation.

To evaluate the effect of RelA methylation on NF-κB activity, we established HEK 293T cells with stable expression of PRMT1-specific shRNA or control shRNA targeting GFP mRNA. Cells expressing shRNA against PRMT1 were characterized by a 70–80% decrease in PRMT1 mRNA and protein levels compared with cells transduced with the control virus (Fig. S6A). The methylation of ectopic RelA was substantially reduced (∼90%) on the silencing of PRMT1 (Fig. 4C), suggesting that PRMT1 is the major methyltransferase mediating RelA asymmetric dimethylation at R30 in vivo.

Fig. S6.

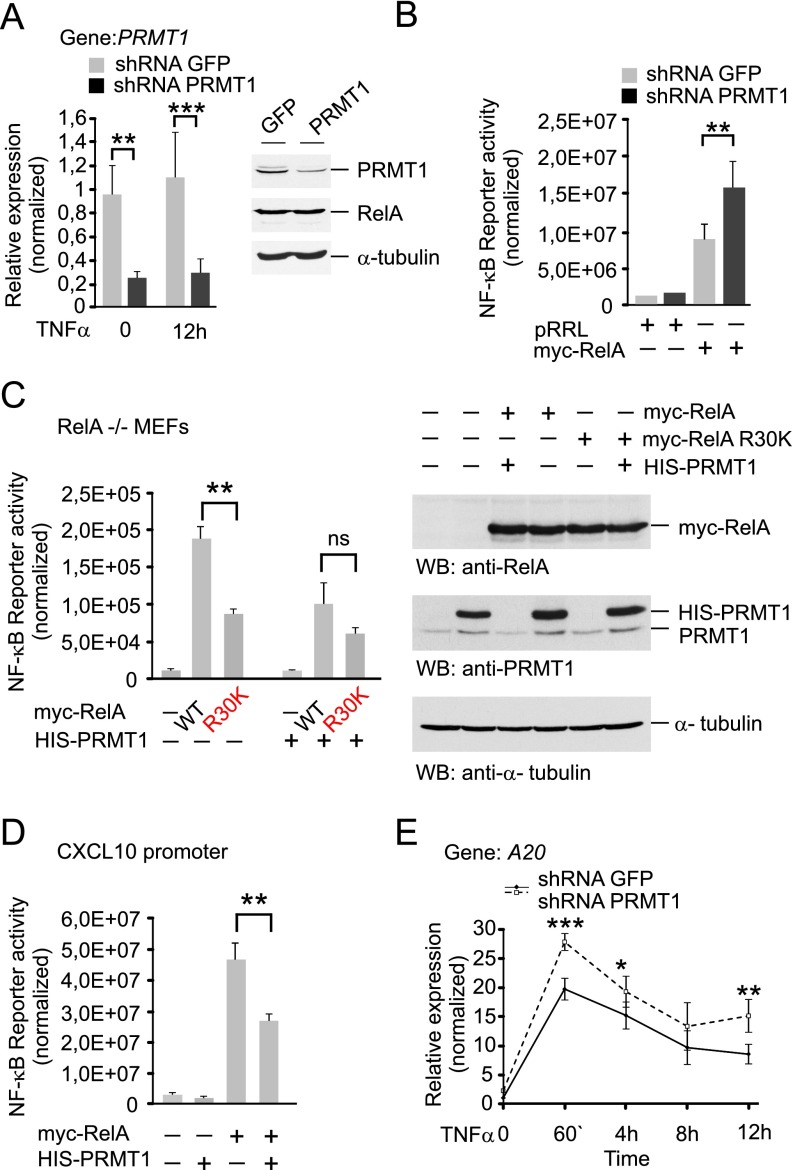

PRMT1 suppresses the transcriptional activity of NF-κB. (A) Characterization of PRMT1 knockdown HEK 293T cells. Expression of PRMT1 mRNA and protein was analyzed by qRT-PCR and immunoblotting, respectively. (B) Transcriptional activity of RelA was measured in HEK 293T cells transfected with GFP- or PRMT1-specific shRNAs alone or cotransfected with a myc-RelA construct using luciferase reporter assays. (C) RelA knockout MEFs were cotransfected with 2×(κB)-luciferase reporter and wild-type or R30K myc-RelA alone or with His-PRMT1 construct. Luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates and normalized to protein content. The expression of ectopic proteins was controlled by immunoblotting (Right). (D) The effect of ectopic expression of His-PRMT1 on the activity of NF-κB was investigated in HEK 293T cells using a reporter containing the κB regulatory element from the CXCL10 gene promoter. (E) Expression of A20 in response to TNFα in control and PRMT1 knockdown cells. Gene-specific mRNA was quantified at the indicated time points after TNFα stimulation using qRT-PCR and the comparative ddCt method. Values are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

We next studied the effect of PRMT1 depletion on NF-κB activity by using a 2×(κB)-luciferase reporter. PRMT1-silenced cells showed elevated levels of the basal, TNFα-induced, or RelA-induced expression of luciferase compared with the control cells (Fig. 4 D and E and Fig. S6B). The ectopic expression of shRNA-resistant PRMT1 had opposite effects and decreased the activity of NF-κB in control and PRMT1-depleted cells. This correlated with an enhanced asymmetric dimethylation of R30 observed on overexpression of PRMT1 (Fig. 4 F and G). The inhibition of NF-κB activity was also seen in RelA−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) when the ectopic wild-type RelA was coexpressed with PRMT1. The mutation of R30 to lysine produced similar repression of NF-κB independent of PRMT1 expression (Fig. S6C). We confirmed these findings by using an alternative NF-κB reporter that contained the κB element from the CXCL10 gene promoter located upstream of the luciferase coding sequence (Fig. S6D). Taken together, these results indicate that PRMT1 inhibits NF-κB reporter activity in vivo, consistent with the lower DNA binding observed for methylated RelA in vitro.

PRMT1 Regulates NF-κB Target Genes in Response to TNFα.

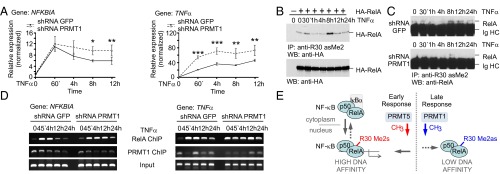

To address the physiological role of PRMT1-mediated RelA methylation, we compared basal and TNFα-induced expression of NF-κB target genes in control and PRMT1 knockdown cells. On silencing of PRMT1, the overall expression of NFKBIA, TNFα, and TNFα-induced protein 3 (A20) mRNAs was enhanced in response to TNFα (Fig. 5A and Fig. S6E), suggesting that PRMT1 down-regulates NF-κB target genes. Interestingly, NFKBIA expression was affected by PRMT1 deficiency only at later time points of TNFα stimulation, whereas activation of TNFα and A20 genes was enhanced throughout the entire treatment in PRMT1-depleted cells. This finding is consistent with the differential regulation of NF-κB target genes by a PRMT1-dependent mechanism that may act in a promoter-specific manner. We did not find any significant difference in the basal expression of tested genes between the control and knockdown cells. This suggests that in the context of native chromatin, PRMT1 represses the agonist-induced transcriptional activity of NF-κB rather than critically controlling the overall inactive state of this transcription factor.

Fig. 5.

PRMT1 regulates NF-κB target genes in response to TNFα. (A) NFKBIA and TNFα gene-specific mRNAs were quantified at the indicated time points after TNFα stimulation using qRT-PCR and the comparative ddCt method. Values are means ± SD of at least three experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (B and C) The time course of methylation of ectopic (B) or endogenous RelA (C) in response to TNFα was analyzed as in Fig. 2C, followed by immunoblotting using anti-HA or anti-RelA (C20) antibodies, respectively. (D) ChIP analysis of promoter occupancy by RelA and PRMT1 in TNFα-treated control and PRMT1 knockdown cells. (E) Model for PRMT1-mediated regulation of NF-κB. In addition to IκB-mediated repression, NF-κB is negatively regulated by methylation of the RelA subunit that is catalyzed by PRMT1. Asymmetric R30 dimethylation in RelA inhibits the transcription of TNFα-induced genes by reducing the DNA binding of NF-κB. Symmetric R30 dimethylation, reported previously by Wei et al. (16), is seen as an NF-κB–activating mark. It is postulated that symmetric and asymmetric RelA dimethylation may represent a specific on/off switch mechanism modulating cytokine-induced NF-κB responses.

PRMT1 Dynamically Associates with TNFα-Inducible Promoters of NF-κB Target Genes and Counteracts RelA Binding.

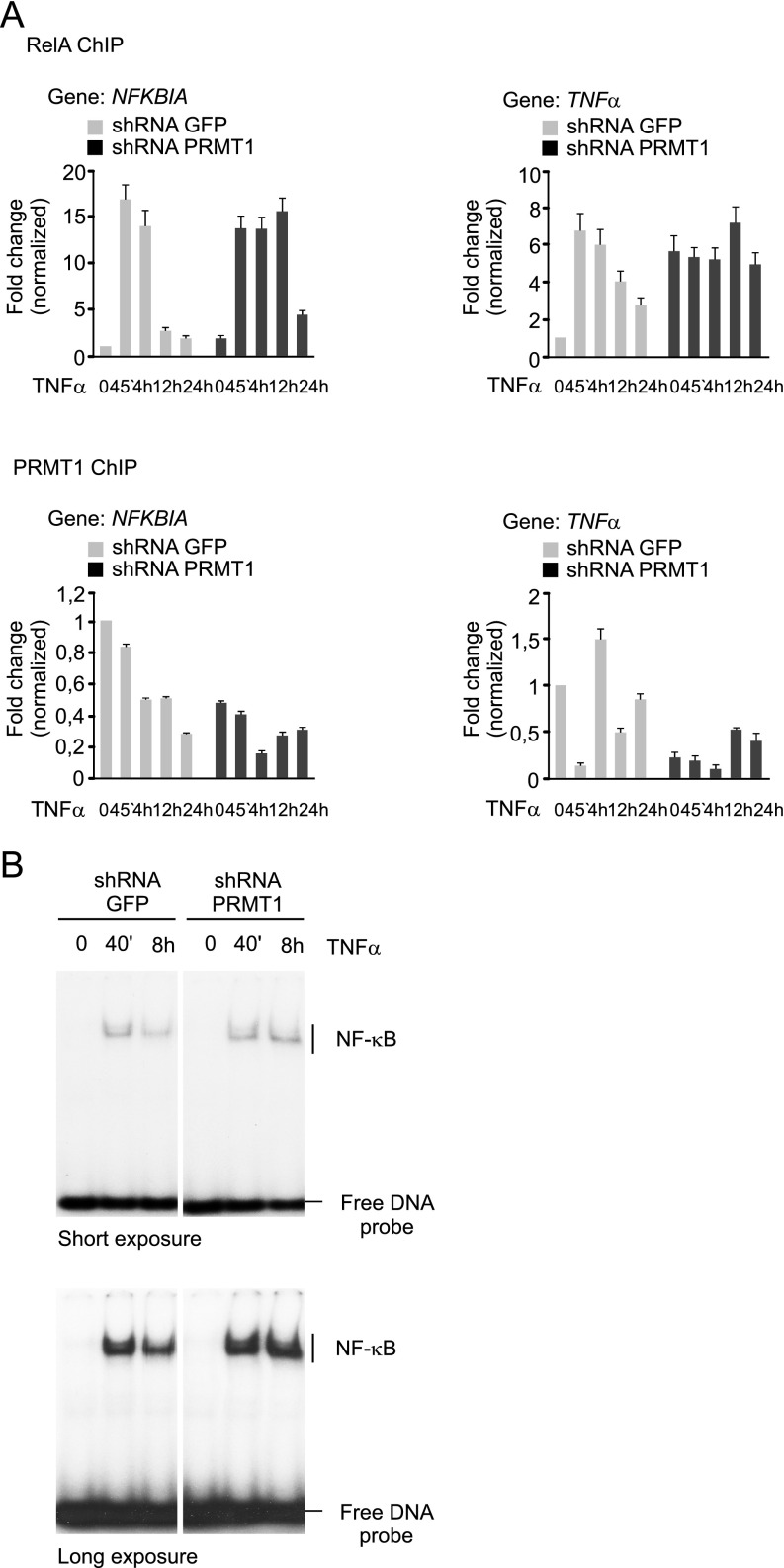

To gain further insight into RelA regulation by asymmetric dimethylation, we examined detailed R30 methylation kinetics in response to TNFα (Fig. 5 B and C). As before, normally growing cells showed weak asymmetric dimethylation of RelA; treatment with TNFα had little or no effect on R30 methylation at early time points, but a substantial increase was observed after 8 h. Methylation of R30 was absent or reduced when the PRMT1 expression was diminished, however (Fig. 5C). The enhanced methylation of R30 was correlated with a rapid decrease in the amount of RelA bound to the NFKBIA and TNFα promoters and coincided in time with the termination of TNFα response (Fig. 5 A and D and Fig. S7A). This effect is consistent with the inhibition of RelA DNA binding by PRMT1-mediated methylation observed in our in vitro and in vivo studies (Fig. 4A and Fig. S7B), implying that PRMT1 may negatively control NF-κB recruitment to genes activated by TNFα.

Fig. S7.

(A) ChIP signals presented in Fig. 5D, normalized to inputs and quantified using ImageJ 1.49 software. (B) EMSA of nuclear extracts obtained from the control or shRNA PRMT1-expressing HEK 293T cells treated with 20 ng/mL TNFα for the indicated times. Distinct parts of the representative gel are separated by white spaces.

To investigate this, we analyzed the binding of RelA or PRMT1 to κB regions of NFKBIA and TNFα genes in control and PRMT1 knockdown cells treated with TNFα. As expected, there was little binding of RelA to the NFKBIA and TNFα promoters under basal conditions, and the level of chromatin-bound RelA increased rapidly in the response of control cells to TNFα (Fig. 5D). Promoter occupancy by RelA remained high during the first 4 h of TNFα treatment, and then declined to almost basal levels after 24 h. In contrast, PRMT1 was found to reside on the NFKBIA promoter even before treatment, and its binding decreased gradually following TNFα stimulation. PRMT1 binding to TNFα differed from that seen for NFKBIA. After stimulation, we observed rapid clearance of PRMT1 from the TNFα promoter, followed by its reappearance after 4 h that coincided in time with NF-κB inactivation. Inducible RelA recruitment to NFKBIA was seen in knockdown cells as well, but PRMT1 depletion decreased the dissociation of RelA from the DNA after 12 h and 24 h of TNFα treatment. This was accompanied by a lower abundance of PRMT1 at the promoter compared with control cells. The PRMT1 signal detected in knockdown cells originated from the remaining protein, as shown in Fig. S6A.

Reduced PRMT1 occupancy on TNFα correlated with enhanced RelA binding to the κB region under both basal and stimulated conditions, suggesting that PRMT1 might control DNA binding of NF-κB in untreated cells as well. The binding of RelA was not sufficient to activate TNFα in the absence of stimulus but was correlated with a greater TNFα transcription, observed already at the early time points of stimulation (Fig. 5 A and D). These data suggest counteraction between the PRMT1 promoter occupancy and RelA binding to the regulatory elements of several NF-κB target genes.

Discussion

Previous studies have implicated a critical role of IκBα degradation/resynthesis in the control of NF-κB. IκBα inhibits the DNA binding of NF-κB and promotes the nuclear export of IκBα–NF-κB complexes, providing negative feedback regulation (7). Other mechanisms target mainly late NF-κB responses and include interactions of the RelA subunit with corepressor proteins, such as Twist1/2 (33), PIAS1 (34), and IκBζ (35). These regulatory mechanisms also include covalent modifications of RelA and its coregulators, such as IKKα-induced phosphorylation of RelA and PIAS1 (34, 36) or PDLIM2-, COMMD1-, and SOCS1-dependent RelA ubiquitination (37, 38), as well as the proteasomal degradation of promoter-bound NF-κB (39). The presence of multiple NF-κB–deactivating mechanisms suggests that the inhibitory function of IκBα is required but not sufficient for the broad range of NF-κB regulation.

Here we report a unique inhibitory mechanism that regulates NF-κB target genes in response to TNFα. This mechanism involves the asymmetric dimethylation of RelA by PRMT1 (Fig. 5E), which inhibits the binding of NF-κB to gene promoters, thereby reducing its transcriptional activity. To explain this effect at the molecular level, we first identified R30 as a PRMT1 methylation site located within the RxxRxRxxC motif of the RelA DNA-binding L1 loop. We then showed that R30 is an important structural residue that not only constitutes a part of the L1 loop, but also critically contributes to its DNA-binding function. Using recombinant RelA proteins purified from E. coli, an organism that lacks arginine methylation, we showed that the R30K mutation per se destabilizes the RHD and inhibits DNA binding (Fig. S4). We concluded that these effects were caused by a change in the amino acid chemistry at this position, which argues for a structural role of R30.

In the crystal structure, R30 is exposed at the surface between the N and C terminal Ig-like subdomains of the RHD (Fig. S2) and can form H bonds with several residues, namely T191, E193, and N186 located within the L3 loop, as well as E279 and, to a lesser extent, D277 from the Lβfßg loop (40). Mutation of R30 to alanine completely abrogated these interactions. Moreover, we found that monomethylation and asymmetric dimethylation of R30 altered H bonding, similar to that observed for the inactivating R30A mutation (Fig. 4B). The loss of H bonds will likely destabilize the interactions between the L1 loop and the rest of the N-terminal domain, thereby increasing the flexibility of the L1 loop as well as possibly altering the side chain positioning of R33, R35, and other DNA-contacting residues. Such structural changes are expected to disrupt DNA binding by the RHD and may possibly explain the inhibition caused by the R30 methylation or mutation.

In addition to dimethylation of R30, MS analysis revealed monomethylation of at least one additional arginine (R236) located in the C terminus of the RHD (Fig. S1C). The predicted low structural accessibility of R236 (Fig. S1A) may possibly explain its monomethylated state, although dimethylation of this residue by PRMT1 cannot be excluded. Interestingly, R236 is adjacent to IκBα-interacting and dimerization interfaces of the RHD (41), raising the possibility that PRMT1 might regulate different functions of RelA through modification of distinct arginines.

PRMT1 functions both to activate and to repress genes (23, 42) by methylating histone H4 and different nonhistone proteins associated with chromatin functions. We have identified PRMT1 as a negative regulator of several NF-κB target genes. Depletion of PRMT1 increased late NFKBIA expression and enhanced overall TNFα and A20 activation by TNFα (Fig. 5A and Fig. S6E). This correlated with the enhanced binding of RelA to gene promoters on TNFα stimulation. We also observed a dynamic association/dissociation of PRMT1 with/from chromatin characterized by different kinetics depending on the specific gene promoters (Fig. 5D). The chromatin association of PRMT1 was not dependent on RelA and also could be detected before TNFα treatment. Moreover, promoter occupancy by PRMT1 was counteracted with the presence of RelA, supporting the inhibitory effect of PRMT1. In agreement with our findings, the inhibition of NFKBIA and IL-8 genes by promoter-associated PRMT1 and PRMT5 has been described previously, but different regulatory mechanisms have been proposed (26). It has been shown that PRMT1 and PRMT5 methylate SPT5 and repress its promoter association and interaction with RNApol II, resulting in a lower rate of transcriptional elongation. It also has been reported that under basal conditions, the ubiquitin ligase activity of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 is impaired by PRMT1-mediated methylation, resulting in inhibition of NF-κB (22). It is likely that PRMT1-mediated regulation of NF-κB target genes requires methylation of other proteins involved in transcription or upstream of NF-κB.

The RelA L1 loop, which is critical for nucleotide sequence recognition and binding, has been shown to be monomethylated at K37 by SET7/9 (12) and symmetrically dimethylated at R30 by PRMT5 (16). These modifications cause an increase in the RelA affinity to DNA and activate NF-κB, in contrast with the inhibitory asymmetric R30 dimethylation by PRMT1 identified in our study. Thus, the RxxRxRxxC motif is modified by different protein lysine and arginine methyltransferases, notably SET7/9, PRMT1, and PRMT5, resulting in methylation-specific marks with distinct biological consequences. Similarly, the asymmetric and symmetric dimethylation of H4R3 by PRMT1 and PRMT5 has either stimulating or repressing effects on genes (23, 24). Evidence has been provided indicating that different effector molecules, such as CBP/p300 and DNMT3a, are recruited to the same histone residue by the presence of either ADMA or SDMA. The exact interplay between these modifications in the control of NF-κB remains unclear, however. Symmetric and asymmetric R30 dimethylation might be counteracting and occurring at different stages of NF-κB responses. Indeed, we found that asymmetric R30 dimethylation is enriched at later time points (Fig. 5 B and C), whereas symmetric dimethylation of this residue seems to be induced shortly after cytokine treatments (16), supporting their distinct regulatory functions. In this context, it could be hypothesized that symmetric/asymmetric R30 dimethylation represents a specific on/off switch mechanism for adjusting cytokine-induced NF-κB responses (Fig. 5E).

In summary, the present study has identified asymmetric arginine dimethylation as a regulatory posttranslational modification of RelA and PRMT1 as a major PRMT responsible for this modification. We report a previously unknown function for PRMT1 in the regulation of TNFα signaling that points to PRMT1 as a restrictive factor controlling NF-κB activity (Fig. 5E). This model is supported by observations that PRMT1 knockdown enhanced the expression of NF-κB target genes by facilitating RelA recruitment to their promoters in response to TNFα. In light of these findings, selective targeting of PRMT1 may be seen as an opportunity to specifically modulate NF-κB–mediated inflammatory and immune responses.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies, protein purification, methylation assays, and molecular dynamics simulations are described in SI Materials and Methods. Virus production and transduction of cells were done as reported previously (9). Quantitative RT-PCR and thermal shift assays were done using SYBR Green- and SYPRO Orange-based detection methods with a PikoReal 96 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). EMSA and luciferase assays have been described previously (9, 18).

SI Materials and Methods

Antibodies.

Anti–c-myc (9E10) (Roche), anti–6×His/HRP-conjugated (Clontech), anti-HA(HA.11) (Covance), anti-RelA(C20) (sc-372; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-PRMT1(MAT-B12) (Abcam) antibodies were obtained from the indicated commercial sources. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the asymmetric dimethylated R30 residue of RelA were raised using NH2-QPKQR-(asMe2)GMRF-COOH peptide. Peptide synthesis, immunization, and affinity purification of the antibodies were performed by Proteogenix.

Plasmids.

The coding region of the RelA fragment (amino acids 1–306) was cloned into the pcDNA 3.1(+)-HA vector to produce the N-terminal HA-tagged version. The HA-tagged RelA fragment was fused to His-tag coding sequences by subcloning into the bacterial expression pET28b(+) vector (Novagen). To produce C-terminal His-tagged RelA constructs, the RelA coding fragments (amino acids 1–306 and 1–107) were inserted into the NdeI and XhoI sites of the pET21b(+) vector (Novagen). The eukaryotic expression plasmids pRRL-myc-RelA, pRRL-myc-RHDL, and pRRL-myc-RHD have been described previously (9). Mutations of R30, R33, and R35 residues were created by site-directed mutagenesis according to the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene). To generate the PRMT1 shRNA vector, oligonucleotides targeting PRMT1 sequence 110–128 were annealed and cloned into the BglII and HindIII sites of pSUPER. The BamHI/SalI fragment containing the PolIII-driven H1 promoter and PRMT1-targeting shRNA sequence was cut out from the resulting plasmid and recloned with the same enzymes into the lentiviral pRDI292 vector. As a control, GFP-targeting pRDI-shRNA-GFP plasmid was generated using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-GATCCCCAACACTTGTCACTACTTTCTCTTTTCAAGAGAAAGAGAAAGTAGTGACAAGTGTTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAAACACTTGTCACTACTTTCTCTTTCTCTTGAAAAGAGAAAGTAGTGACAAGTGTTGGG-3′.

Eukaryotic and bacterial expression plasmids pcDNA3.1-His-myc-hPRMT1, pGEX6p-1-hPRMT1, pGEX6p-1-PRMT4, and pGEX6p-1-PRMT6 were obtained by cloning the corresponding PCR products into pcDNA3.1(+)-HIS-myc and pGEX6p-1 vectors, respectively.

Proteins.

HIS-tagged RelA and GST-tagged PRMT proteins were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus-RIL (Stratagene) and purified by affinity chromatography on an ÄKTA Purifier System using HisTrap and GSTrap columns (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Calf thymus histones (type II-AS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cells and Retroviral Transduction.

HEK 293T cells and RelA−/− MEFs were routinely grown in DMEM supplemented with GlutaMAX, 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. To produce viruses, HEK 293T cells were transfected with 3.5 μg of the envelope pMD.G plasmid, 6.5 μg of the packaging pCMVDR8.91 plasmid, and 10 μg of pRDI-shRNA-GFP or pRDI-shRNA-PRMT1. After 24 h, the viral supernatants were collected and used to infect fresh HEK 293T cells. At 48 h posttransduction, the cells were split into selective medium containing 20 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). After three rounds of selection, the antibiotic concentration was reduced to 10 μg/mL.

Transfections and Luciferase Assays.

Transient transfections of cells were performed using calcium phosphate precipitation. For luciferase assays, cells were transiently transfected with pGL3-2×(κB)-luc plasmid or pGL3 reporter plasmid containing the 533-bp sequence upstream of the transcription start site of the mouse CXCL10 gene. Various expression plasmids coding for shRNAs and wild-type or mutated myc-RelA or their corresponding empty vectors were cotransfected as indicated in the figures. Unless stated otherwise, cells were collected at 24 h posttransfection and analyzed for luciferase activity using the Promega Luciferase Assay System according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and normalized to protein concentrations.

Protein Interaction Assays.

GST-PRMT1 or GST alone immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) were incubated with HA-tagged RelA protein (amino acids 1–306) in buffer containing 50 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 µg/mL aprotinin, and 1 μg/mL pepstatin) for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed three times with the same buffer and heated at 95 °C for 5 min in SDS/PAGE sample buffer. Precipitated proteins were resolved on a 10% (wt/vol) SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody.

For purification of PRMT1-RelA complexes, HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with myc-tagged RelA and His-myc-PRMT1 or control expression vector. Cells were incubated for 24 h and then lysed in EB4 buffer (40 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 µg/mL aprotinin, and 1 μg/mL pepstatin) supplemented with 20 mM imidazole. Insoluble fractions were removed by centrifugation at 15,800 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and supernatants were incubated with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen). After extensive washing, samples were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min in SDS/PAGE sample buffer and used for further analysis.

For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, HEK 293T cells were stimulated with 20 ng/mL TNFα for the indicated times or left untreated. Cells were lysed in EB4 buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and then centrifuged at 15,800 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were incubated with NF-κB RelA (C-20) AC beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 °C overnight. Immunoprecipitates were washed four times with the lysis buffer, and immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted by incubating beads at 95 °C for 5 min in SDS/PAGE sample buffer.

Methylation Assays.

Purified recombinant proteins were incubated with GST-PRMT1, GST-PRMT4, or GST-PRMT6 in 30 μL of methylation buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.9 and 114 mM NaCl) supplemented with 0.8 µCi 3H-SAM (GE Healthcare) or 1.3 mM SAM (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at 30 °C. Reactions were stopped either by adding 2× SDS/PAGE sample buffer, followed by heating at 95 °C for 5 min, or by freezing at −20 °C.

MS Analysis.

Proteins solved in 100 mM NH4HCO3 buffer (pH 8.0) were reduced with 10 mM DTT at 56 °C for 30 min and then alkylated with 55 mM iodacetamide at room temperature for 20 min. Samples were digested with chymotrypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 23 °C for 4 h. The tryptic peptides were purified using ZipTip C18 pipette tips (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions before nano-LC-ESI-MS analysis. Samples were analyzed with an UltiMate 3000 nano-HPLC system coupled to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a Nanospray Flex ionization source. The peptides were separated on a fritless fused-silica microcapillary column (75 µm i.d. × 280 µm o.d. × 10 cm long) packed with 3 µm of reversed-phase C18 material (ReproSil; Dr. Maisch).

The Q Exacitve HF mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent mode, selecting the top 20 most abundant isotope patterns with a charge >1 from the survey scan with an isolation window of 1.6 mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Survey full-scan MS spectra were acquired from 300 to 1,750 m/z at a resolution of 60,000 with a maximum injection time of 120 ms and automatic gain control target 1e6. The selected isotope patterns were fragmented by higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) with normalized collision energy of 28 at a resolution of 15,000 with a maximum injection time of 120 ms and automatic gain control target 5e5.

Data analysis was performed using Proteome Discoverer 1.4.1.14 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the Sequest search engine. The raw files were searched against the H. sapiens database (20,164 entries) extracted from the UniProt database. Precursor and fragment mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively, and up to two missed cleavages were allowed. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine, oxidation of methionine, and monomethylation and dimethylation of lysine and arginine were set as variable modifications. Peptide identifications were filtered at 1% false discovery rate.

EMSA.

Different amounts of recombinant proteins or nuclear extracts were incubated in EMSA buffer containing 10 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 65 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/mL BSA, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 50 ng/µl poly(dI-dC), and 32P-labeled double-strand oligonucleotide (5′-AATTCGGGACTTTCCCGTCGGGACTTTCC-3′) for 45 min at 30 °C. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved by native 4% (wt/vol) PAGE, and radioactive signals were visualized by autoradiography.

Fluorescence-Based Thermal Shift Assay.

The thermal shift assays were performed using the PikoReal 96 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) melt curve program with a ramp rate of 7 °C/s and a temperature range of 25–95 °C. All reactions were incubated in a 25-µL final volume and assayed in 96-well plates using SYPRO Orange (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 µM purified recombinant protein diluted in buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 225 mM NaCl, and 2.25% (vol/vol) glycerol. The double-stranded oligonucleotide (40 nM) used in the EMSA reaction was applied to assess the DNA-binding–dependent thermal stabilization. Midpoint temperatures of the protein-unfolding transition (Tm) were calculated using PikoReal 96 Real-Time PCR System software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

qRT-PCR.

HEK 293T cells stably expressing shRNAs were treated with 20 ng/mL TNFα for the indicated times. Total RNA was isolated with a RiboPure Kit (Ambion) and evaluated for yield and purity by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000; PeqLab), and 2 µg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using a high-capacity cDNA reverse-transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA samples were stored at −20 °C until use. qRT-PCR was performed using human PRMT1-specific (5′-GAGAATTTTGTAGCCACCTTGG-3′ and 5′-CCTGGCCACAGGACACTT-3′), NFKBIA-specific (12), TNFα-specific (5′-TGAGGCCAAGCCCTGGTAT-3′ and 5′-CGAGATAGTCGGGCCGATT-3′), A20-specific (5′-CTGCCCAGGAATGCTACAGATAC-3′ and 5′-GTGGAACAGCTCGGATTTCAG-3′)-, and L32-specific primers (12) and the DyNAmo Flash SYBR Green qPCR Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with subsequent detection of the melting curves using the StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and PikoReal 96 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was initially activated by incubating reactions at 95 °C for 10 min. Here 1 µL of cDNA was used for amplification in a 10-µL reaction volume during 40 cycles (denaturation step at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing/elongation step at 60 °C for 1 min). The results were normalized to the expression of ribosomal protein L32 mRNA and quantified by the comparative ddCt method.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP).

Cells were stimulated with 20 ng/mL TNFα and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde added directly to the medium for 10 min at room temperature. The cross-linking was stopped by adding glycine to the final concentration of 125 mM. After a 5-min incubation at room temperature, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS, scraped, and pelleted by centrifugation at 800 × g. Then 2.0 × 107 cells were lysed for 5 min in L1 buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol] supplemented with protease inhibitors. Nuclei were collected at 800 × g in a microfuge and resuspended in L2 buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0, 1% (wt/vol) SDS, and 5 mM EDTA) along with 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 µg/mL aprotinin. Chromatin was shared to yield fragments of 200–1,000 bp using a sonifier (Branson) equipped with a microtip (5× 10 s at constant 40 W and 20% power output). Sonicated lysates were centrifuged, and the resulting supernatant was diluted 10-fold with ChIP dilution buffer containing 16.7 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.1, 167 mM NaCl, 0.01% SDS, 1.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (Merck), and 1.2 mM EDTA. Diluted lysates were precleared for 1 h with 55 µL of a 50% suspension of protein A Sepharose supplemented with 0.2 µg/µL sonicated herring sperm DNA and 0.5 µg/µL BSA.

Immunoprecipitations were performed using anti-RelA(C20) or anti-PRMT1(MAT-B12) antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Immune complexes were collected with protein A Sepharose, washed once with low-salt wash buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.1, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (Merck), and 2 mM EDTA], once with high-salt wash buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.1, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (Merck), and 2 mM EDTA], once with LiCl wash buffer [10 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.1, 250 mM LiCl, 1% (wt/vol) sodium deoxycholate, 1% (vol/vol) IGEPAL-CA630 (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mM EDTA], and finally twice with TE buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0 and 1 mM EDTA).

Protein-DNA complexes were eluted from antibodies with elution buffer containing 1% SDS and 0.1 M NaHCO3, incubated in the presence of 192 mM NaCl for 4 h at 65 °C, and digested with proteinase K for 1 h at 45 °C. DNA was recovered by phenol/chloroform extraction and precipitation with ethanol in the presence of an inert carrier, such as glycogen (Roche). Approximately 1/30 of precipitated DNA and gene-specific primers (NFKBIA: 5′-GACGACCCCAATTCAAATCG-3′ and 5′-TCAGGCTCGGGGAATTTCC-3′; TNFα: 5′-AACCGAGACAGAAGGTGCAG-3′ and 5′-TGTGCCAACAACTGCCTTTA-3′) were used in the qRT-PCR analyses.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations.

Molecular dynamics simulations of the RelA:p50 heterodimer bound to DNA were performed using the X-ray structure described by Escalante et al. (Protein Data Bank ID code 2I9T) (29). Structures were protonated using Protonate3D of the Molecular Operating Environment. Resolved water molecules were retained, and a water cap of 12 Å around the protein–DNA complex was added. Methylations were introduced at the solvent-accessible side of R30. The alanine mutant was created by the removal of subsequent side chain atoms of R30, yielding a total of four systems comprising native R30, monomethylated R30, asymmetric dimethylated R30, and an R30A mutant.

The AMBER package (ambermd.org/) was used for simulations, applying the AMBER force field 99SB-ILDN for the protein and ff99-parmbsc0 for the DNA. For monomethylated and dimethylated arginines, charges of nonmethylated arginines were preserved by splitting partial charges of the redundant hydrogen(s) in analogy to parameters for trimethyllysine (43). Additional angle and torsion terms were imported from the AMBER and GAFF force fields. After an extensive equilibration protocol (44), sampling trajectories of 100 ns were collected for each system. Simulation analyses included overall stability checks via root mean square deviations of atoms, as well as local hydrogen-bonding analysis, applying a default distance cutoff of 3.0 Å between heavy atoms and a default angle cutoff of 135° between hydrogen-bonding atoms.

Statistics.

Results are presented as mean ± SD for variation between experiments. Statistical comparisons were calculated using the Student t test. P values are denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We thank Didier Trono for retroviral constructs; Johanna E. Mayrhofer, Christoph Dotter, and M. Imran Khan for technical assistance; and Ilja Vietor for critical comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge the High-Performance Computing platform at the University of Innsbruck for providing access to the Leo-II computer cluster. This work was supported by Austrian Science Fund Grant P24251 (to T.V.). J.E.F. is the recipient of a DOC fellowship from the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1522372113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cone JB. Inflammation. Am J Surg. 2001;182(6):558–562. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00822-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Inflammation and oncogenesis: A vicious connection. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baud V, Karin M. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor and its relatives. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11(9):372–377. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18(49):6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann A, Baltimore D. Circuitry of nuclear factor kappaB signaling. Immunol Rev. 2006;210:171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: The control of NF-[κ]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beg AA, Baldwin AS., Jr The I κ B proteins: Multifunctional regulators of Rel/NF-κ B transcription factors. Genes Dev. 1993;7(11):2064–2070. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang TT, Kudo N, Yoshida M, Miyamoto S. A nuclear export signal in the N-terminal regulatory domain of IkappaBalpha controls cytoplasmic localization of inactive NF-kappaB/IkappaBalpha complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(3):1014–1019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valovka T, Hottiger MO. p65 controls NF-κB activity by regulating cellular localization of IκBβ. Biochem J. 2011;434(2):253–263. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitz ML, Mattioli I, Buss H, Kracht M. NF-kappaB: A multifaceted transcription factor regulated at several levels. ChemBioChem. 2004;5(10):1348–1358. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins ND. Post-translational modifications regulating the activity and function of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25(51):6717–6730. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ea CK, Baltimore D. Regulation of NF-kappaB activity through lysine monomethylation of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(45):18972–18977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910439106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang XD, et al. Negative regulation of NF-kappaB action by Set9-mediated lysine methylation of the RelA subunit. EMBO J. 2009;28(8):1055–1066. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu T, et al. Regulation of NF-kappaB by NSD1/FBXL11-dependent reversible lysine methylation of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(1):46–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912493107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy D, et al. Lysine methylation of the NF-κB subunit RelA by SETD6 couples activity of the histone methyltransferase GLP at chromatin to tonic repression of NF-κB signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(1):29–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei H, et al. PRMT5 dimethylates R30 of the p65 subunit to activate NF-κB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(33):13516–13521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311784110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris DP, Bandyopadhyay S, Maxwell TJ, Willard B, DiCorleto PE. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α induction of CXCL10 in endothelial cells requires protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5)-mediated nuclear factor (NF)-κB p65 methylation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(22):15328–15339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.547349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covic M, et al. Arginine methyltransferase CARM1 is a promoter-specific regulator of NF-kappaB–dependent gene expression. EMBO J. 2005;24(1):85–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganesh L, et al. Protein methyltransferase 2 inhibits NF-kappaB function and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(10):3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3864-3874.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassa PO, Covic M, Bedford MT, Hottiger MO. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 coactivates NF-kappaB–dependent gene expression synergistically with CARM1 and PARP1. J Mol Biol. 2008;377(3):668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Lorenzo A, Yang Y, Macaluso M, Bedford MT. A gain-of-function mouse model identifies PRMT6 as a NF-κB coactivator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(13):8297–8309. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tikhanovich I, et al. Dynamic arginine methylation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 6 regulates Toll-like receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(36):22236–22249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.653543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, et al. Methylation of histone H4 at arginine 3 facilitating transcriptional activation by nuclear hormone receptor. Science. 2001;293(5531):853–857. doi: 10.1126/science.1060781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Q, et al. PRMT5-mediated methylation of histone H4R3 recruits DNMT3A, coupling histone and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(3):304–311. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng S, et al. Arginine methylation-dependent reader-writer interplay governs growth control by E2F-1. Mol Cell. 2013;52(1):37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwak YT, et al. Methylation of SPT5 regulates its interaction with RNA polymerase II and transcriptional elongation properties. Mol Cell. 2003;11(4):1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, Xue Y, Huang N, Yao X, Sun Z. MeMo: A web tool for prediction of protein methylation modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web server issue):W249–W253. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shien DM, et al. Incorporating structural characteristics for identification of protein methylation sites. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(9):1532–1543. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Escalante CR, Shen L, Thanos D, Aggarwal AK. Structure of NF-kappaB p50/p65 heterodimer bound to the PRDII DNA element from the interferon-beta promoter. Structure. 2002;10(3):383–391. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00723-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bikkavilli RK, et al. Dishevelled3 is a novel arginine methyl transferase substrate. Sci Rep. 2012;2:805. doi: 10.1038/srep00805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar S, Rabson AB, Gélinas C. The RxxRxRxxC motif conserved in all Rel/kappa B proteins is essential for the DNA-binding activity and redox regulation of the v-Rel oncoprotein. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(7):3094–3106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen YQ, Sengchanthalangsy LL, Hackett A, Ghosh G. NF-kappaB p65 (RelA) homodimer uses distinct mechanisms to recognize DNA targets. Structure. 2000;8(4):419–428. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Šošić D, Richardson JA, Yu K, Ornitz DM, Olson EN. Twist regulates cytokine gene expression through a negative feedback loop that represses NF-kappaB activity. Cell. 2003;112(2):169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu B, et al. Proinflammatory stimuli induce IKKalpha-mediated phosphorylation of PIAS1 to restrict inflammation and immunity. Cell. 2007;129(5):903–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Totzke G, et al. A novel member of the IkappaB family, human IkappaB-zeta, inhibits transactivation of p65 and its DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(18):12645–12654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence T, Bebien M, Liu GY, Nizet V, Karin M. IKKalpha limits macrophage NF-kappaB activation and contributes to the resolution of inflammation. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1138–1143. doi: 10.1038/nature03491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maine GN, Mao X, Komarck CM, Burstein E. COMMD1 promotes the ubiquitination of NF-kappaB subunits through a cullin-containing ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 2007;26(2):436–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka T, Grusby MJ, Kaisho T. PDLIM2-mediated termination of transcription factor NF-kappaB activation by intranuclear sequestration and degradation of the p65 subunit. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(6):584–591. doi: 10.1038/ni1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saccani S, Marazzi I, Beg AA, Natoli G. Degradation of promoter-bound p65/RelA is essential for the prompt termination of the nuclear factor kappaB response. J Exp Med. 2004;200(1):107–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang DB, Chen YQ, Ruetsche M, Phelps CB, Ghosh G. X-ray crystal structure of proto-oncogene product c-Rel bound to the CD28 response element of IL-2. Structure. 2001;9(8):669–678. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00635-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phelps CB, Ghosh G. Discreet mutations from c-Rel to v-Rel alter kappaB DNA recognition, IkappaBalpha binding, and dimerization: Implications for v-Rel oncogenicity. Oncogene. 2004;23(6):1229–1238. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu MC, Lamming DW, Eskin JA, Sinclair DA, Silver PA. The role of protein arginine methylation in the formation of silent chromatin. Genes Dev. 2006;20(23):3249–3254. doi: 10.1101/gad.1495206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu Z, Lai J, Zhang Y. Importance of charge-independent effects in readout of the trimethyllysine mark by HP1 chromodomain. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(41):14928–14931. doi: 10.1021/ja904951t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallnoefer HG, Handschuh S, Liedl KR, Fox T. Stabilizing of a globular protein by a highly complex water network: A molecular dynamics simulation study on factor Xa. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114(21):7405–7412. doi: 10.1021/jp101654g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]