Significance

Influenza is a rapidly spreading acute respiratory infection that causes profound morbidity and mortality. Established CD8+ T-lymphocyte (CTL) immunity directed at conserved viral regions provides protection against distinct influenza A viruses (IAVs). In this study, we show that public T-cell receptors (TCRs) specific for the most prominent human CTL epitope (M158–66 restricted by HLA-A*0201) are capable of recognizing sporadically emerging variant IAVs. We also identify the structural mechanisms that enable promiscuous TCR recognition in this context. Our analysis suggests that preexisting cross-reactive TCRs may limit the spread of newly emerging pandemic IAVs.

Keywords: influenza infection, human CD8+ T cells, T-cell receptor

Abstract

Memory CD8+ T lymphocytes (CTLs) specific for antigenic peptides derived from internal viral proteins confer broad protection against distinct strains of influenza A virus (IAV). However, immune efficacy can be undermined by the emergence of escape mutants. To determine how T-cell receptor (TCR) composition relates to IAV epitope variability, we used ex vivo peptide–HLA tetramer enrichment and single-cell multiplex analysis to compare TCRs targeted to the largely conserved HLA-A*0201-M158 and the hypervariable HLA-B*3501-NP418 antigens. The TCRαβs for HLA-B*3501-NP418+ CTLs varied among individuals and across IAV strains, indicating that a range of mutated peptides will prime different NP418-specific CTL sets. Conversely, a dominant public TRAV27/TRBV19+ TCRαβ was selected in HLA-A*0201+ donors responding to M158. This public TCR cross-recognized naturally occurring M158 variants complexed with HLA-A*0201. Ternary structures showed that induced-fit molecular mimicry underpins TRAV27/TRBV19+ TCR specificity for the WT and mutant M158 peptides, suggesting the possibility of universal CTL immunity in HLA-A*0201+ individuals. Combined with the high population frequency of HLA-A*0201, these data potentially explain the relative conservation of M158. Moreover, our results suggest that vaccination strategies aimed at generating broad protection should incorporate variant peptides to elicit cross-reactive responses against other specificities, especially those that may be relatively infrequent among IAV-primed memory CTLs.

Preexisting CD8+ T-lymphocyte (CTL) immunity directed at peptides derived from internal viral proteins is known to confer protection against specific strains of influenza A virus (IAV) (1–5). Recalled memory CTLs generated by seasonal variants can also expedite virus elimination and host recovery following infection with H1N1, H2N2, H3N2, H5N1, and H7N9 IAVs (2, 3, 6–9). However, it is unclear why such cross-strain responses vary among individuals. The ability of αβ T-cell receptors (TCRαβs) to recognize antigenic epitopes from distinct IAVs and circumvent immune escape relies on peptide sequence conservation and/or structural homology (10–12). A detailed understanding of cross-strain reactivity in relation to defined TCRαβ interactions may therefore inform the rational development of a universal vaccine against IAV.

The conserved HLA-A*0201–restricted M158–66 (GILGFVFTL, referred to hereafter as “M158”) (13) and variable HLA-B*07 superfamily-restricted NP418–426 (LPFERATVM, referred to hereafter as “NP418”) (10) peptides are the most immunogenic IAV epitopes described in humans. The M158 epitope has remained unchanged in seasonal and pandemic IAVs since 1918 (1, 8, 14, 15), although viruses with single-alanine-substitution mutants of M158 generated by reverse genetics are replication competent (16). Accordingly, the M158 peptide is an ideal vaccine candidate for >1 billion people globally who express HLA-A*0201. In contrast, the NP418 epitope is hypervariable, encompassing >20 different naturally occurring sequences. Analysis of HLA-B*07/B*35–restricted NP418-specific CTLs in the wake of the 2009 pandemic revealed at least two distinct responses to this prominent epitope (12).

In this study, we used ex vivo tetramer enrichment combined with single-cell multiplex RT-PCR to dissect TCRαβ signatures within CTL populations specific for the HLA-A*0201-M158 and HLA-B*07/B*35-NP418 epitopes. Our data indicate that public A*0201-TCRαβs use molecular mimicry to recognize distinct IAVs.

Results

Natural IAV M158 Variants Emerge in HLA-A2.1 Transgenic HHD Mice.

The HLA-A*0201–restricted M158 peptide is broadly conserved across IAVs, although the M1-I2M and M1-L3W variants have been found in 21% of H5N1 sequences (7). Using the influenza resource database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information, we aligned 1,000 full-length sequences representing IAV subtypes infecting different species between 1918 and 2010 to conduct an in-depth validation of M158 conservation. Mutations were found in 8.2% of IAVs, and 11 distinct M158 substitutions were identified across all positions bearing the C-terminal P8 and P9 residues (Table 1). The most frequent M158 mutations occurred at the anchor residue (p2), accounting for nearly 67% of all substitutions in the database (M1-I2M, 42%; M1-I2V, 23%; M1-I2T, 1.2%). Although these M158 variants were detected mainly in avian IAVs (H2, H5, H6, H7, H9, H11, and H13), 8 of the 82 mutant sequences were derived from human isolates.

Table 1.

Newly identified naturally occurring M158 peptide variants

| GILGFVFTL | Mutant | No. | % | Source | Year | Subtype | Strain |

| A- - - - - - - - | G1A | 1 | 0.1 | Human | 2009 | H3N2 | A/Tomsk/02/2009 |

| W- - - - - - - - | G1W | 1 | 0.1 | Swine | 2005 | H3N2 | A/swine/Guangdog/01/2005 |

| -V- - - - - - - | I2V | 19 | 1.9 | Avian | 1999–2008 | H3N2, H5N1, H7N7, H7N2, H7N3, H9N2, H2N1 | A/Hanoi/TN405/2005 |

| -M- - - - - - - | I2M* | 35 | 3.5 | Avian | 1999–2008 | H5N1, H6N2, H9N2 | A/duck/Hong Kong/140/1998 |

| -T- - - - - - - | I2T | 1 | 0.1 | Avian | 2002 | H5N1 | A/duck/Fujian/13/2002 |

| - -W- - - - - - | L3W* | 0 | 0.0 | Avian | H5N1 | Described in ref. 7 | |

| - - -E- - - - - | G4E | 1 | 0.1 | Avian | 1998 | H9N2 | A/chicken/Anhui/1/1998 |

| - - - -V- - - - | F5V | 2 | 0.2 | Human, avian | 1946, 2000 | H1N1, H9N2 | A/Cameron/1946 |

| - - - -L- - - - | F5L | 9 | 0.9 | Human, avian | 1983–2009 | H1N1, H5N2, H7N3, H11N2 | A/Canterbury/236/2005 |

| - - - - -I - - - | V6I | 12 | 1.2 | Human, avian | 1967–2006 | H2N2, H13N6, H1N2, H3N1, H1N1 | A/England/10/1967 |

| - - - - - -Y- - | F7Y | 1 | 0.1 | Human | 1999 | H3N2 | A/New South Wales/15/1999 |

| Total mutations | 82 | ||||||

| Total sequences | 998 | 8.2 |

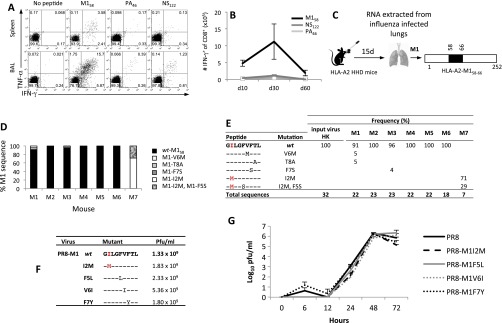

An established mouse model of IAV escape (17) was used to probe the emergence of M158 mutants. As in humans, the M158 epitope is immunodominant in HLA-A2.1 HHD mice (Fig. S1 A and B). Amino acid substitutions in M158 were encoded by viral RNA extracted from the lungs of three of seven mice 15 d after infection (Fig. S1 C–E), a lower mutation rate compared with the immunodominant H2-DbNP366 epitope in WT B6 mice (17). Engineered PR8 viruses carrying the M1-I2M, M1-F5L, M1-V6I, and M1-F7Y mutations grew to similar titers in embryonated eggs and MDCK cell cultures (Fig. S1 F and G). However, it remains possible that subtle differences in viral fitness may counterselect against M158 mutants in the natural setting. The absence of epitope-specific immune pressure also may lead to the occurrence of viral refugia in individual cases, a phenomenon widely recognized in the ecology field.

Fig. S1.

M158–66 mutants emerge during influenza virus infection in HLA-A2.1 HHD mice. (A) CD8+ T-cell responses to M158, PA46, and NS122 at the acute influenza phase (day 10 after HK-H3N2 infection) were assessed by TNFα/IFNγ ICS in spleen and BAL cells from HHD-A2.1 mice. Representative dot plots are shown. (B) The numbers of spleen A2-M158+CD8+, A2-PA46+CD8+, and A2-NS122+ CD8+ T cells at days 10, 30, and 60 following HK infection in HHD-A2.1 mice. (C) HHD-A2.1 mice were infected intranasally with HK-H3N2 virus, and lungs were harvested 15 d after infection. RNA was extracted from infected lungs, and viral cDNA was synthesized and amplified by PCR, cloned, subjected to a second round of PCR, and sequenced; (D and E) Data represent the mutation frequency (%) of total sequences. As a control, the input HK viral stock M158 peptide region was sequenced with no additional mutations isolated. The MHC-I anchor position is shown in grey. (F) A panel of PR8 viruses with specific mutations within M158–66 generated by reverse genetics. (G) The replicative fitness of the mutated viruses was compared with that of the WT-PR8 virus in MDCK cells. MDCK monolayers were infected with WT PR8 (rescued by reverse genetics) or mutant PR8-M1-I2M, M1-F5L, M1-V6I, and M1-F7Y viruses at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. Culture supernatants were harvested at various time points ranging from 5 min to 72 h. Data represent the mean ± SD.

Sequence variation within M158 therefore occurs in IAVs recovered from humans (8.2%) and from experimentally infected HLA-A2.1 HHD mice (7.3%). However, unlike the frequent and persistent mutations in NP418 (10), these M158 variants are not readily fixed in circulating human IAVs. To determine whether the contrasting patterns of viral variation within M158 and NP418 reflect immune selection, we undertook a detailed cellular and molecular evaluation of the corresponding CTL responses.

HLA-A*0201-M158+ CTLs Are Immunodominant and Recognize M158 Variants.

Using direct ex vivo tetramer-based magnetic enrichment (4, 18) to minimize selection bias, we analyzed CTL responses specific for HLA-A*0201-M158 (A2-M158) and HLA-B*3501-NP418 (B35-NP418) in individual subjects expressing both HLA-A*0201 and HLA-B*3501 (Fig. 1 and Table S1). A2-M158+ CTLs were identified with a single conserved tetramer, and B35-NP418+ CTLs were identified with a tetramer pool corresponding to the main variants from 1918, 1934, 1947, 1980, and 2002 (12). The A2-M158+ CTL population was consistently larger (17 ± 9.2-fold) than the B35-NP418+ CTL population (Fig. 1A), which frequently predominates in HLA-A*0201− donors (Fig. S2). Furthermore, the polyclonal A2-M158+ CTLs recognized all detected mutants, although response frequencies varied and the M1-G4E mutant was weakly immunogenic in five donors (Fig. 1B). Conversely, the polyclonal B35-NP418+ CTLs recognized a limited number of variants (Fig. 1C), in line with previous reports of immune escape (10, 12). Thus, M158-specific TCRs cross-react with a broader spectrum of naturally occurring epitope variants compared with NP418-specific TCRs. It is notable in this regard that NP418 variants are often composite, incorporating up to three amino acid substitutions, whereas single mutations are more common in M158.

Fig. 1.

Ex vivo immunodominance of A2-M158+ over B35-NP418+ CTLs. (A) Costaining of A2-M158+ and B35-NP418+ CTLs directly ex vivo by tetramer enrichment showing (i) single tetramer+CD8+CD4−CD14−CD19− cells and (ii) fold-increase of the A2-M158 above the B35-NP418 CTL response. (B and C) Recognition of naturally occurring M158 (B) and NP418 (C) variants by human PBMCs from A2+B35+ donors was assessed 10 d after restimulation using intracellular staining for IFN-γ production in response to the indicated peptides. Data show individual subjects (S).

Table S1.

Human PBMCs used in the study

| Subject | HLA-A | HLA-B | Age* |

| 1† | 2402, 3002 | 3501, 4402 | 41 |

| 3† | 0301, 1101 | 3501, 4402 | 41 |

| 4 | 3201, 1101 | 3501, 3503 | 28 |

| 9† | 0201, 6801 | 4402, 5101 | 22 |

| 10 | 0201, 1101 | 4001, 4402 | 26 |

| 13† | 0201, 3002 | 1805, 2705 | 31 |

| 15 | 0201, 0301 | 0702, 3901 | 59 |

| 16 | 0201, 1101 | 3501, 3901 | 25 |

| 17 | 0201, 1101 | 3501, 3901 | 27 |

| 18† | 0201, 0101 | 3501, 0801 | NA |

| 19† | 0201, 0101 | 3501, 0801 | NA |

| 20† | 0201, NA | 3501, NA | NA |

| 21 | 0201, 1101 | 3501, 1401 | 29 |

| 22† | 0201, 0201 | 0702, 4402 | 56 |

| 23† | 02, 24‡ | 07, 40+ | NA |

| 40† | 0301 | 0702, 3501 | 62 |

| 43† | 0101, 0301 | 0801, 3501 | 69 |

| 44† | 0101, 3201 | 0801, 3501 | 66 |

| 61† | 0301 | 0702, 3501 | 69 |

| LIFT 7 | 0201, 0101 | 0702, 0801 | 61 |

| LIFT 9 | 0201, 3401§ | 1301§, 4001 | 30 |

| LIFT 11 | 0201, 3401§ | 1301§, 5601§ | 45 |

HLA type was determined by molecular typing. HLA types in bold are of interest for this study.

Age at time of collection; NA, not available from donor information.

Subject sample acquired from a buffy pack (Australian Red Cross Blood Service).

Only two-digit typing was performed.

Alleles strongly associated with Indigenous Australians.

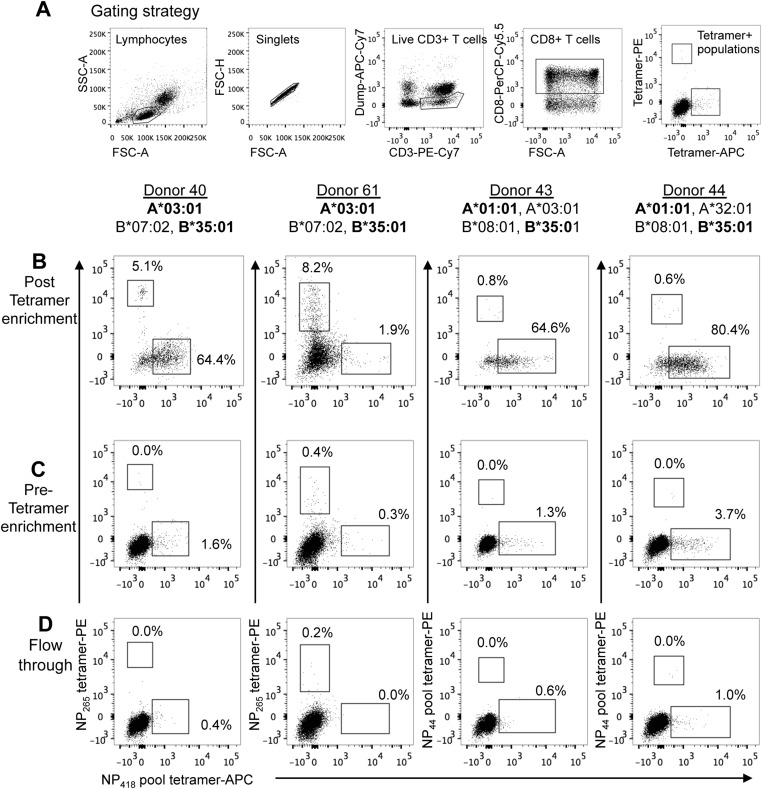

Fig. S2.

Differential immunodominance hierarchies of B35-NP418+ CTLs in healthy A2−B35+ donors. Costaining of B35-NP418+ CTLs with A3-NP265+ (subjects 40 and 61) or A1-NP44 pool+ CTLs (subjects 43 and 44) directly ex vivo by tetramer enrichment are shown. (A) Tetramer+ cells were gated on viable CD4−CD14−CD19−CD3+CD8+ cells following a sequential gating strategy. (B–D) Representative FACS plots of post-enriched (B), pre-enriched (C), and flowthrough (D) fractions are gated on CD8+ T cells to show tetramer-costaining profiles. The A3-NP265 epitope encodes for the ILRGSVAHK peptide sequence, and the A1-NP44 pool consists of the WT CTELKLSDY and the S7N-variant.

Dissection of A2-M158 and B35-NP418 TCRαβ Repertoires.

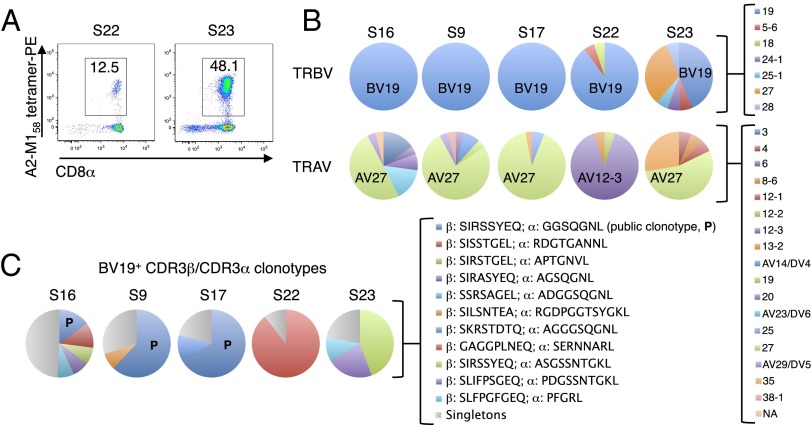

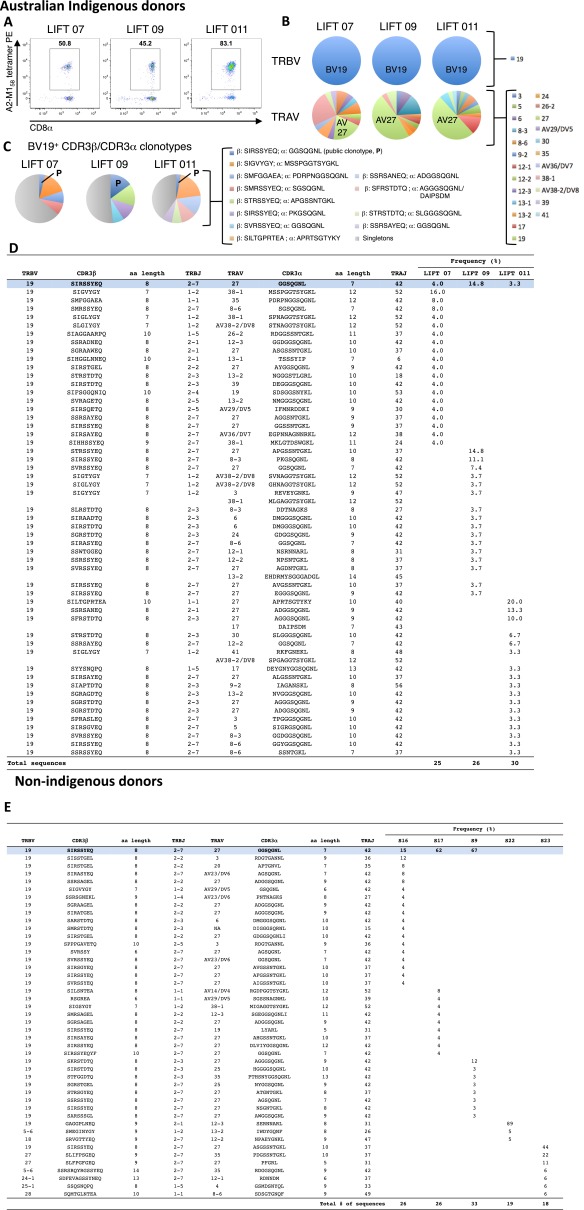

Consistent with previous reports (19–21), direct ex vivo single-cell sequencing of the A2-M158+ TCRαβ repertoire showed a heavy bias toward T-cell receptor β variable 19 (TRBV19) use across all eight donors, coupled with a dominant T-cell receptor α variable 27 (TRAV27) segment in seven of eight donors (Fig. 2 A and B and Fig. S3 A and B). The averaged frequency for TRBV19 was 91.6% (range 44–100%), compared with 49.2% (range 0–91%) for TRAV27. The most common TCRαβ signature was the public clonotype TRBV19/complementarity-determining region (CDR)3β-SIRSSYEQ paired with TRAV27/CDR3α-GGSQGNL (Fig. 2C and Fig. S3 C–E). In subject 23, the public TRBV19/CDR3β-SIRSSYEQ paired with a similar TRAV27/CDR3α-ASGSSNTGKL (44% of sequences), whereas subject 22 exhibited a limited TCRαβ repertoire in which an alternate TCRβ (TRBV19/CDR3β-GAGGPLNEQ) paired with a non-TRAV27 TCRα (TRAV12.3/CDR3α-SERNNARL). Public TCRαβ clonotypes can therefore be generated in the majority of HLA-A2+ individuals across different ethnicities, including Indigenous Australians.

Fig. 2.

The A2-M158+ TCRαβ repertoire is dominated by a public clonotype. A2-M158+ CTLs were isolated directly ex vivo from non-Indigenous healthy donors (n = 5) by magnetic enrichment and flow cytometric sorting of single tetramer+ cells. Populations were gated on viable Dump−tetramer+CD3+CD8+ events. (A) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing tetramer+CD8+ T cells after ex vivo enrichment. (B) TRBV and TRAV use. (C) Frequency of CDR3αβ clonotypes. Corresponding data for healthy Indigenous Australian donors (n = 3) are shown in Fig. S3. P, public.

Fig. S3.

The A*0201-M158 TCRαβ repertoire is dominated by a shared public TCRαβ clonotype in Indigenous Australians. A2-M158+CD8+ T cells were isolated from healthy donors by magnetic enrichment of A2-M158 tetramer-binding cells and single-cell sorting. Populations were gated as viable Dump−CD3+CD8+A2-M158tetramer+ cells. Paired amino acid CDR3αβ diversity analysis was performed for HLA-A*0201-M158+CD8+ T-cell response directly ex vivo from Indigenous Australians (n = 3) (A–D) and nonindigenous donors (n = 5) (E). (A) FACS profiles of A2+M158+CD8+ T cells after ex vivo tetramer enrichment. (B) TRBV and TRAV gene use. (C) The frequency of CDR3α-CDR3β clonotypes. (D and E) The abundance of particular CDR3β/CDR3α clonotypes in Indigenous Australian (D) and nonindigenous (E) donors. The prominent BV19+ population is highlighted in blue. TCRαβ repertoires of sorted cells were analyzed using a TCRαβ multiplex protocol.

Reflecting the prevalence of low-frequency private clonotypes, the M158-specific TCRαβ repertoire was more diverse (12.4 ± 6.0 CDR3αβ pairs per donor) than previously reported. Furthermore, the AGA(Gn)GG CDR3α motif (22) (in which “n” denotes any number of residues) found by others following long-term culture was not consistently present in our direct ex vivo dataset, although two glycines (GG) featured in 20 of the 45 CDR3α sequences. The CDR3β IRS motif, which forms the basis for “peg–notch” JM22 TCR recognition of the “plain vanilla” M158 epitope (21), was used in 11/45 CDR3β sequences across five donors.

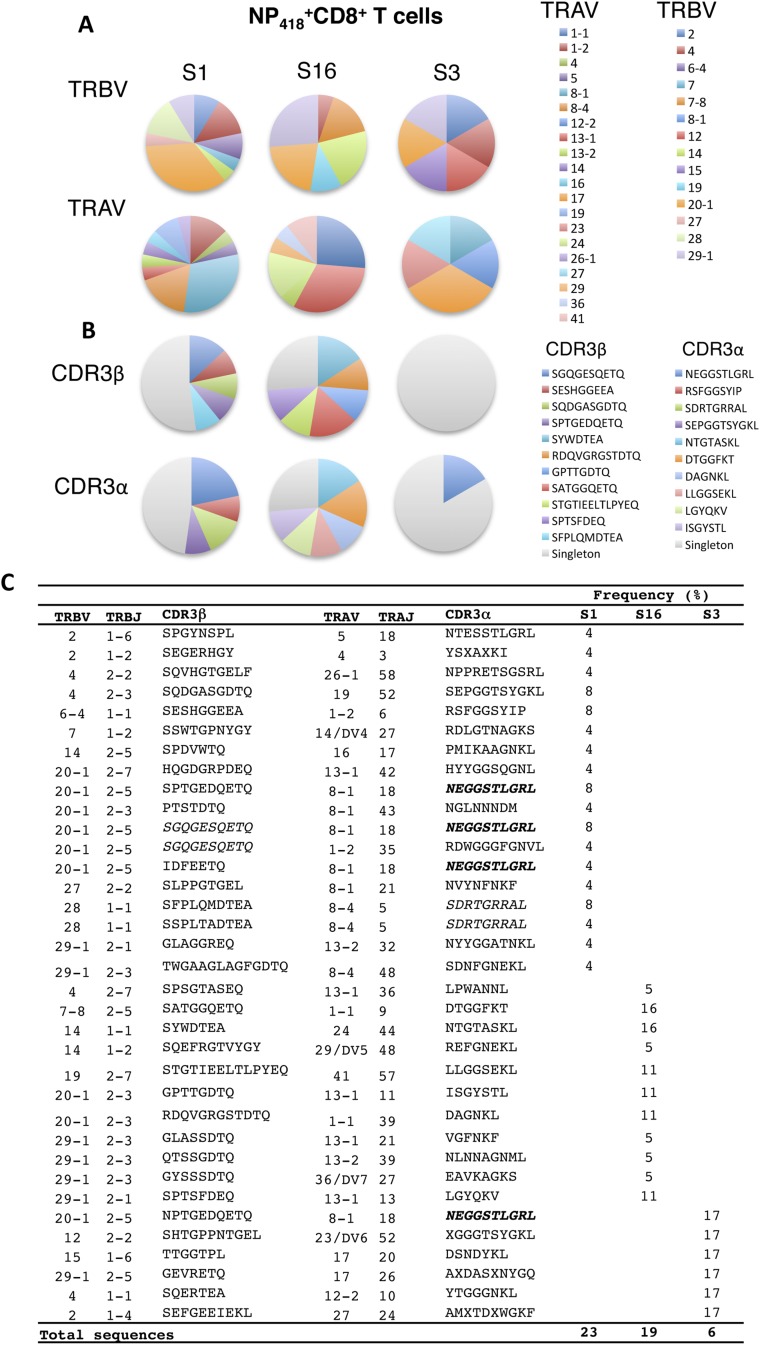

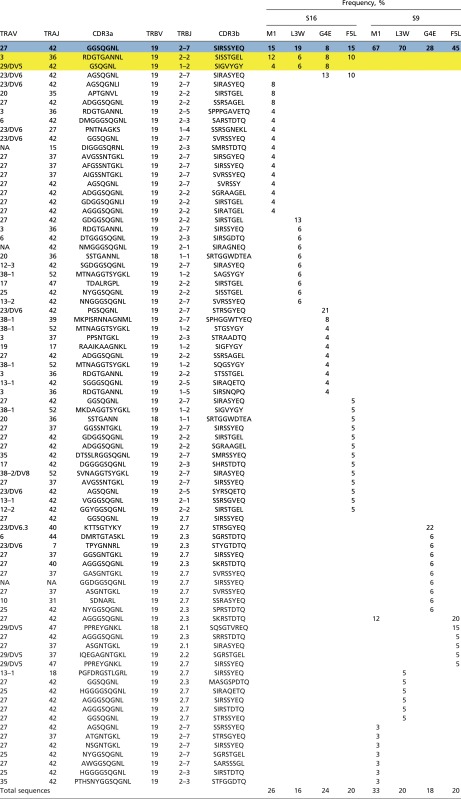

In contrast, analysis of the B35-NP418+ TCR repertoire using pooled B35-NP418 tetramers (Fig. S4) revealed distinct CDR3α/CDR3β sequences incorporating diverse TRAV and TRBV segments. A preference for TRBV20-1/TRBJ5-1 rearrangements with a CDR3β length of 7 or 10 amino acids was observed in the TCRβ repertoire, whereas the predominant TCRα chains favored TRAV8-1 and TRAJ18 with a CDR3α length of 8–10 amino acids (Table S2). However, only one common sequence (TRAV8-1/CDR3α-NEGGSTLGRL) was found among individuals (Fig. S4).

Fig. S4.

The total-NP418 TCRαβ repertoire is private and lacks dominant clonotypes. PBMCs from B*3501+ healthy donors were subjected to magnetic enrichment with a pool of NP418 tetramers [1918 (LPFERATIM), 1934 (LPFDRTTIM), 1947 (LPFDKTTIM), 1980 (LPFEKSTVM), and 2002 (LPFEKSTIM)] and then were stained with anti–CD8-APC. Single B35+NP418+CD8+ T cells were sorted and analyzed by single-cell multiplex TCRαβ RT-PCR. Paired amino acid CDR3αβ diversity profiles for HLA-B*3501-NP418+CD8+ T-cell response directly ex vivo from three healthy donors are shown. (A) The frequency of TRAV and TRBV use for the total NP418 TCR repertoire. (B and C) CDR3αβ sequences repeated across donors are depicted in bold, and sequences repeated within donors are depicted in italics. “x” indicates the sequence could not be determined.

Table S2.

Summary of CDR3β and CDR3α TCR repertoire for human HLA-A201-M158+CD8+ and HLA-B*3501+NP418+CD8+ T-cell responses ex vivo

| A2+M158 | B3501+NP418 | |

| Number of subjects | 8 | 3 |

| HLA type | A*02:01 | B*3501 |

| NP418 tetramer | — | 1918, 1934, 1947, 1980, 2002 |

| Number of CDR3αβ sequences | 203 | 48 |

| Predominant TRBV | 19 | 20–1 |

| Predominant TRAV | 27 | 8–1, 13–1 |

| Predominant TRBJ | 2–7 | 2–5, 2–3 |

| Predominant TRAJ | 42 | 18 |

| Predominant CDR3β length | 8 | 10 |

| Predominant CDR3α length | 7 | 10 |

| No. CDR3β per subject | 11.25 ± 5.55 | 11.33 ± 5.51 |

| No. CDR3α per subject | 11.88 ± 5.77 | 10.67 ± 4.51 |

| No. CDR3αβ per subject | 12.75 ± 6.27 | 11.67 ± 6.03 |

| CDR3αβ Simpson’s diversity | 0.75 ± 0.27 | 0.97 ± 0.03 |

There was no overlap between the B35-NP418+ TCR datasets, generating a Morisita–Horn statistic of 1 (zero interindividual similarity). However, the A2-M158+ TCR datasets overlapped considerably, driven by the public TRBV19/CDR3β-SIRSSYEQ sequence (averaged Morisita–Horn statistic of 0.6). These differences were statistically significant (P = 0.0056, Wilcoxon signed tank test). In addition, the Simpson diversity index was higher for B35-NP418+ TCRαβs (0.97 ± 0.03) than for A2-M158+ TCRαβs (0.75 ± 0.27) (Table S2).

Thus, dominant public TCRαβ clonotypes (TRBV19/TRAV27) are selected in HLA-A*0201+ donors responding to the relatively invariant A2-M158 epitope, whereas TCRαβ clonotypes directed at the hypervariable B35-NP418 epitope are more diverse across individuals.

Public M158-Specific TCRαβ Clonotypes Cross-Recognize Newly Identified Variants.

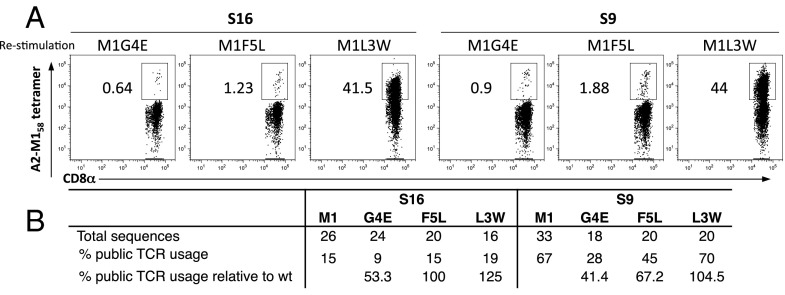

How do A2-M158+ CTLs recognize naturally occurring M158 variants? To investigate this question, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stimulated with the mutant peptide (M1-L3W, -G4E, or -F5L) for 10 d and then stained with the M158 WT tetramer. In this way, variant-specific CTLs were amplified by the mutant peptide, and cross-reactive clonotypes identified by reactivity with the M158 WT tetramer were characterized using single-cell CDR3αβ TCR repertoire diversity analysis (Fig. 3 and Table S3). The variant M1-L3W, M1-G4E, and M1-F5L peptides represent naturally occurring M158 mutants, with a CTL response magnitude hierarchy of M1-L3W > M1-F5L > M1-G4E in subject 9 and subject 16 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The A2-M158+ TCRαβ repertoire cross-recognizes M158 peptide variants. (A) A2+ PBMCs were restimulated for 10 d in vitro with the M158 variant peptides M1-G4E, M1-F5L, or M1-L3W and then stained with the M158 WT tetramer. Thus, TCRs were selected to recognize the mutant by the 10-d restimulation and to recognize the cross-reactive WT epitope by tetramer sort. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown gated on CD8+ T cells after the exclusion of CD4+CD14+CD19+ events. (B) Summary of public TCRαβ use.

Table S3.

Paired amino acid CDR3β and CDR3α diversity profiles for mutant-specific HLA-A*0201-M158+ CD8+ T-cell responses restimulated in vitro with variant M158 peptides

|

The public TCR clonotype is highlighted in blue and bold. The common TCR clonotype for S16 is highlighted in yellow.

The public HLA-A*0201-M158+ TCR (CDR3α-GGSQGNL; CDR3β-SIRSSYEQ) recognized all three peptide variants (Table S3), although the frequency was slightly lower for the M1-G4E mutant (47% of the WT). Higher-frequency public TCRαβ use correlated with larger mutant-specific CTL responses (Fig. 1B), indicating that public HLA-A*0201-M158+ TCRs play an important role in variant cross-recognition. Overall, the mutant M158 peptides selected a TCRαβ repertoire comparable to that of WT M158 with similar TRAV27, TRAJ42, TRBV19, and TRBJ2-7 use (except for M1-G4E in subject 16, which used TRAV23DV/6 instead of the typically dominant TRAV27), suggesting that WT HLA-A*0201-M158+ TCRs are largely cross-reactive with M158 variants.

HLA Presentation and TCR Recognition of M158 Variants.

To determine the impact of peptide mutation on HLA binding and T-cell recognition, we assessed the extent to which the naturally occurring M158 mutant peptides M1-F5L, M1-G4E, and M1-L3W stabilize HLA-A*0201. We refolded the HLA-A*0201 molecule with the M158 peptide and each of the three variants to determine the thermal stability of the corresponding peptide-HLA (pHLA) complexes. In complex with the M158 peptide, HLA-A*0201 exhibited a thermal melt point (Tm, the temperature required to unfold 50% of the protein) of ∼66 °C; the Tm was similar for the three M158 variants (Table S4), indicating that the mutations directly affect TCR binding rather than pHLA complex stability.

Table S4.

Stability of pHLA complexes

| pHLA | Tm, °C |

| HLA-A*0201-M158 | 65.8 ± 1.2 |

| HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L | 65.6 ± 0.6 |

| HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E | 66.0 ± 0.2 |

| HLA-A*0201-M1-L3W | 65.9 ± 0.6 |

To understand the mode of recognition of M158 mutants by public HLA-A*0201-M158+ TCRs, we conducted surface plasmon resonance studies with the previously characterized M158-specific JM22 TCR (TRAV27/CDR3α-AGSQGNL; TRBV19/CDR3β-SSRSSYEQ) (21). We confirmed that the JM22 TCR binds with high affinity (1.79 μM) to the HLA-A*0201-M158 complex (21, 23), but measured substantially lower affinities for the three M158 variants (Table S5). Namely, weak binding (Kd >200 μM) characterized the JM22 TCR interaction with M1-G4E and M1-F5L, and this was further diminished (Kd >600 μM) for M1-L3W, presented by HLA-A*0201 (Table S5). Thus, although the JM22 TCR can recognize all M158 variants, the binding affinity is lower for the mutant epitopes (24).

Table S5.

Surface plasmon resonance

| pHLA | Kd, μM |

| HLA-A*0201-M158 | 1.79 ± 0.5 |

| HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L | >200 |

| HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E | >200 |

| HLA-A*0201-M1-L3W | >600 |

M158 Variants No Longer Form Plain Vanilla Epitopes.

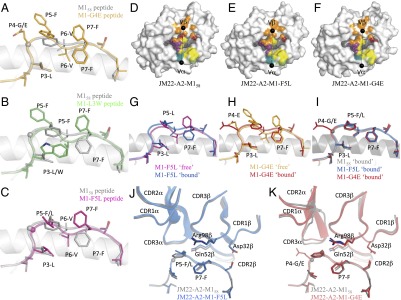

To understand the impact of the naturally occurring M158 mutations on epitope presentation and T-cell recognition, we determined the structures of three binary pHLA complexes (M1-F5L, M1-G4E, and M1-L3W) (Fig. 4 and Table S6) and compared these structures with the previously solved structure of HLA-A*0201-M158 (23). The M158 epitope is considered plain vanilla because the M158 epitope adopts a flat surface in the cleft of HLA-A*0201 (25) (Fig. 4A). Indeed, despite containing two aromatic residues (P5-Phe and P7-Phe), these side chains are buried inside the antigen-binding cleft, leaving the P6-Val solvent exposed. The overall structure of the M1-G4E mutant complex is similar to that of the M158 complex, with rmsds of 0.25 Å for the antigen-binding cleft and 0.27 Å for the peptide (Fig. 4A). Although the replacement of the glycine residue by glutamic acid does not disturb the backbone conformation for M1-G4E, it allows P6-Val to move deeper into the HLA-A*0201 antigen-binding cleft (Fig. 4A). As a result, P5-Phe and P7-Phe are mobile and adopt several conformations, most of which are solvent exposed (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Structural analysis of M158 variants in complex with HLA-A*0201 and the JM22 TCR. (A–C) HLA-A*0201 is represented as a white cartoon with the peptide in stick form (M158 in white, M1-G4E in orange, M1-L3W in green, M1-F5L in pink). The glycine Cα is represented as a sphere. (D–F) The JM22 TCR footprint on the surface of HLA-A*0201 (white) in complex with M158 (D), M1-F5L (E), and M1-G4E (F) peptide (gray). The HLA and peptide atoms are colored teal, green, and purple when contacted by CDR1α, CDR2α, and CDR3α, respectively, and red, orange, and yellow when contacted by CDR1β, CDR2β, and CDR3β, respectively. The black spheres represent the JM22 TCR center of mass for the Vα and Vβ domains. (G) Superimposition of HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L free (pink) and bound to the JM22 TCR (blue). (H) Superimposition of HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E free (orange) and bound to the JM22 TCR (red). (I) Superimposition of HLA-A*0201-M158 (gray), HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L (blue), and HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E (red) bound to the JM22 TCR. (J and K) Superimposition of JM22 TCR-HLA-A*0201-M158 (dark gray) with the JM22 TCR-HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L (blue) and JM22 TCR-HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E (red) complexes.

Table S6.

Data collection and refinement statistics for HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E, HLA-A*0201-M1-L3W, and HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L

| HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E | HLA-A*0201-M1-L3W | HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L | |

| Data collection statistics | |||

| Temperature | 100K | 100K | 100K |

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions, a, b, c, Å | 53.50, 80.43, 57.23 | 53.65, 80.15, 57.61 | 53.77, 80.20, 57.44 |

| ° | β = 113.81 | β = 114.42 | β = 114.18 |

| Resolution, Å | 48.95–1.90 (2.00–1.90) | 48.85–2.10 (2.21–2.10) | 46.57–2.03 (2.14–2.03) |

| Total no. of observations | 265,021 (38,181) | 196,977 (28,599) | 106,306 (14,990) |

| No. of unique observations | 35,010 (5,053) | 26,019 (3,776) | 28,609 (4076) |

| Multiplicity | 7.6 (7.6) | 7.6 (7.6) | 3.7 (3.7) |

| Data completeness, % | 100.0 (100.0) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.4 (96.8) |

| I/σI | 9.4 (2.6) | 11.7 (3.6) | 10.6 (2.0) |

| Rpim*, % | 7.1 (48.1) | 8.4 (52.8) | 7.1 (42.4) |

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Water | 435 | 173 | 327 |

| Rfactor†, % | 16.99 | 17.00 | 17.11 |

| Rfree†, % | 20.93 | 22.71 | 21.49 |

| Rmsd from ideality | |||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.043 | 1.050 | 1.080 |

| Ramachandran plot, % | |||

| Favored | 98.2 | 98.7 | 98.5 |

| Allowed | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Outliers | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Rpim = Σhkl [1/(N-1)]1/2 Σi | Ihkl, i - <Ihkl> |/Σhkl <Ihkl>.

Rfactor = Σhkl | | Fo | - | Fc | |/Σhkl | Fo | for all data except ∼ 5% which were used for Rfree calculation.

More dramatic rearrangements were observed for the M1-L3W (Fig. 4B) and M1-F5L (Fig. 4C) variants. The P3-Leu of the WT M158 peptide is buried in the cleft and interacts with the B pocket of HLA-A*0201, whereas the larger P3-Trp of M1-L3W is accommodated in the B pocket without modification of the overall antigen-binding cleft structure (rmsd of 0.33 Å). However, the M1-L3W peptide must rearrange dramatically due to the presence of the large tryptophan residue at P3 (rmsd of 0.61 Å) (Fig. 4B). The P5-Phe side chain swings out of the antigen-binding cleft to avoid steric clashes with P3-Trp and hence becomes solvent exposed. As a consequence, P6-Val is buried in the antigen-binding cleft, and P7-Phe is again mobile and solvent exposed (Fig. 4B). Thus, in the HLA-A*0201-M1-L3W structure, the two large aromatic side chains at P5 and P7 are directly available for TCR interaction.

Similarly, the M1-F5L variant adopts a different peptide conformation (rmsd of 0.44 Å) without distorting the antigen-binding cleft (rmsd of 0.29 Å) (Fig. 4C). Even though P5-Leu is smaller than P5-Phe, the rotamer of the leucine side chain (like P5-Phe) does not allow docking inside the antigen-binding cleft without changing the overall backbone of the peptide. The P3-Leu therefore no longer interacts with the B pocket of HLA-A*0201 and instead becomes mobile and solvent exposed. The new conformation of the P5-Leu residue also impacts the P6-Val conformation, which becomes buried in the antigen-binding cleft, whereas P7-Phe is now solvent exposed and mobile (Fig. 4C).

Overall, these surprising structures of the M158 variants demonstrate that interplay between peptide residues constrains the conformation of the M158 epitope, with any alterations reflecting either the inherent flexibility of particular residues (in M1-G4E and M1-F5L) or steric hindrance (in M1-L3W). As a consequence, single substitutions at different positions in the peptide can transform the plain vanilla M158 epitope into a more featured antigen.

The Public JM22 TCR Recognizes M158 Variants via Induced-Fit Molecular Mimicry.

To understand how HLA-A*0201-M158+ CTLs recognize the naturally occurring epitope variants (Fig. 1B), we determined the structures of the JM22 TCR (21) in complex with HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E and HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L (Table S7). As in the WT M158 complex (Fig. 4 D–F), the JM22 TCR docks orthogonally on the two M158 variant peptides presented by HLA-A*0201 (rmsd of 1.1 Å and 0.7 Å with the M1-G4E and M1-F5L complexes, respectively). The M1-G4E and M1-F5L peptides change conformation upon JM22 TCR binding (Fig. 4 G and H) to mimic that of the WT M158 peptide (Fig. 4I). These structural rearrangements allow key residues (23) from the JM22 TCR β-chain (identified via mutagenesis), namely D32, Q52, and R98, to maintain critical interactions with both the peptide and HLA-A*0201. The requirement for conformational change also explains why the JM22 TCR binds HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E and HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L with lower affinities than HLA-A*0201-M158 (Fig. 4 G and H).

Table S7.

| JM22-HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E | JM22-HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L | |

| Data collection statistics | ||

| Temperature | 100K | 100K |

| Space group | C2 | C2 |

| Cell dimensions, a, b, c, Å | 233.66, 49.03, 113.04 | 242.88, 47.30, 185.95 |

| ° | β = 115.95 | β = 115.49 |

| Resolution, Å | 48.69–2.95 (3.11–2.95) | 46.53–2.50 (2.64–2.50) |

| Total no of observations | 186,480 (27,394) | 246,060 (36,028) |

| No. of unique observations | 24,843 (3,602) | 67,001 (9,700) |

| Multiplicity | 7.5 (7.6) | 3.7 (3.7) |

| Data completeness, % | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.8 (99.9) |

| I/σI | 12.1 (2.2) | 7.7 (2.1) |

| Rpim* (%) | 7.2 (44.2) | 7.4 (41.1) |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Water | ||

| Rfactor†, % | 23.59 | 21.63 |

| Rfree† % | 28.87 | 28.92 |

| Rmsd from ideality | ||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.002 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles, ° | 0.581 | 1.170 |

| Ramachandran plot, % | ||

| Favored | 98.9 | 95.8 |

| Allowed | 0.74 | 4.0 |

| Outliers | 0.36 | 0.2 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution-shell.

Rpim = Σhkl [1/(N-1)]1/2 Σi | Ihkl, i - <Ihkl> |/Σhkl <Ihkl>.

Rfactor = Σhkl | | Fo | - | Fc | |/Σhkl | Fo | for all data except ∼ 5% which were used for Rfree calculation.

The leucine substitution at p5 (M1-F5L) is accommodated without rearrangements of the JM22 TCR CDR loops (Fig. 4J) (23), whereas the JM22 TCR docking angle is slightly different when in complex with M158 and M1-G4E (78° and 80°, respectively) (Fig. 4 D and F). This difference is a direct result of the P4-Glu substitution, which causes a 1-Å shift of the CDR3α loop to avoid steric clashes with the P4-Glu (Fig. 4K). The key JM22 TCR β-chain residues identified via mutagenesis (23), namely D32, Q52, and R98, conserve their critical interactions with both the peptide and the HLA molecule despite the P4-Glu and P5-Leu substitutions. Thus, the lower affinity of the JM22 TCR for HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L and HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E can be attributed to structural changes in the corresponding peptides, as well as to the CDR3α loop in the case of M1-G4E, following TCR binding (Fig. 4 G and H, respectively). Given the structural rearrangement of the M1-G4E and M1-F5L peptides, it is anticipated that large changes would occur in the M1-L3W peptide, resulting in an even lower affinity for the JM22 TCR (Table S5).

These ternary structures show that a public TCRαβ can recognize naturally occurring M158 variants via induced-fit molecular mimicry, potentially explaining why this epitope is conserved among influenza viruses circulating in the human population.

Discussion

Diversity in the TCR repertoire has been associated with high-avidity recognition of MHC-peptide antigens, effective viral clearance, and the containment of immune escape (26, 27). In this study, we used a multiplex single-cell RT-PCR (28, 29) to determine whether TCRαβ diversity and/or composition are associated with immune escape in influenza virus infection. The broad recognition spectrum of a public TRAV27/TRBV19+ TCR within the M158-specific CTL repertoire correlated with the relative scarcity of naturally occurring epitope variants. Such public A2-M158+ TCRs were found to be highly prevalent across donors, including HLA-A*0201+ non-Indigenous donors and Indigenous Australians (HLA-A*0201 frequency of 30–50% and 10–15%, respectively). It is notable in this regard that Indigenous Australians are at greater risk of severe influenza disease, especially when new IAVs emerge (9, 30, 31). Nonetheless, preexisting CTL memory characterized by best-fit public TCRs may confer protection in the context of HLA-A*0201.

The ternary structure of a public TCR bound to the plain vanilla HLA-A*0201-M158 complex (21, 23) showed previously that the central arginine residue within the predominant CDR3β IRS motif (21) is required to allow a peg–notch interaction. We extended this analysis to naturally occurring M158 mutants and found that the same public TCR can recognize naturally occurring variants via induced-fit molecular mimicry, incurring a penalty in terms of binding affinity and T-cell activation. Moreover, the extent of variant recognition correlated with the prevalence of public TCRs, possibly explaining the hierarchical differences in TCR affinity (G4E/F5L > L3W) and T-cell activation (L3W > F5L > G4E). Donors with prominent public TCR use (e.g., subject 9, 67%) recognized the majority of M158 mutants, and the converse was true for donors with limited public TCR use (e.g., subject 16, 15%). These observations suggest that public TCRs may limit, at least to some extent, the establishment of mutant strains within the circulating pool of human IAVs. This idea is consistent with an earlier report in which public Mamu-A*01-CM9181–specific TCRs were shown to predict the outcome of simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus macaques (32).

Mutant peptides incorporating substitutions at TCR contact sites within the B35-NP418 epitope (reflecting nine decades of natural selection) can be recognized by at least two distinct sets of cross-reactive CTLs specific for either ER or DK motifs at P4-5 (11). In theory, accurate identification of the key solvent-exposed residues and motifs that allow variable peptides to elicit cross-reactive CTL responses could inform the development of rationally designed peptide-mosaic vaccines against unpredicted IAVs (1, 33). Unlike the A2-M158+ CDR3αβ repertoire, however, the NP418+ CDR3αβ repertoire in B7+ and B35+ donors is diverse and private, potentially facilitating the emergence of novel NP418 variants. In turn, these mutated epitopes will likely elicit de novo TCR repertoires. Successive waves of variant exposure and diverse TCR recruitment may therefore favor the emergence and perpetuation of NP418 mutant IAVs (34).

Structural analyses revealed that single-amino acid substitutions within the M158 peptide can transform this rather flat epitope into conformations that are no longer plain vanilla (25). Although the featureless morphology of HLA-A*0201-M158 determines the character of the highly biased TCR repertoire (21, 25), our data show that structurally prominent M158 variants select a similar array of TCRs. This counterintuitive finding can be explained, at least in part, by the observation that public TCRs (exemplified by JM22) can reshape such variants into conformations that resemble the WT M158 epitope, which is optimal for immediate binding without the need for structural rearrangements. Such induced-fit molecular mimicry was reported previously for an Epstein–Barr virus-specific TCR (35).

In summary, we show here that HLA-A*0201–restricted public TCR clonotypes elicited by the WT M158 epitope can cross-recognize naturally occurring peptide variants. Conversely, the HLA-B*3501–restricted NP418 epitope selects a diverse and largely private CDR3αβ repertoire, which correlates with frequent mutational escape and the ongoing circulation of variant IAVs (12, 16). The ability of vaccine-induced CTL responses to protect against variable pathogens should therefore be considered in the context of individual peptides and individual TCRs.

Methods

PBMC Isolation.

PBMCs were processed and HLA-typed from randomly selected buffy packs (Melbourne Blood Bank) and healthy donors, with informed written consent (Table S1). Experiments conformed to the National Health and Medical Research Council Code of Practice and were approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research.

Ex Vivo Tetramer Enrichment and Phenotypic Analysis.

Lymphocytes (1–8×106) were stained with HLA-A*0201-M158 or HLA-B*3501-NP418 tetramers conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE) or PE-Cy7. The NP418 response was represented by the 1918 (LPFERATIM), 1934 (LPFDRTTIM), 1947 (LPFDKTTIM), 1980 (LPFEKSTVM), and 2002 (LPFEKSTIM) variants (12). Samples were incubated with anti-PE microbeads and tetramer-PE/PE-Cy7+ cells were enriched via magnetic separation (36), then stained with anti–CD4-APC-H7, anti–CD8-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti–CD14-APC-Cy7, anti–CD19-APC-Cy7, anti–CD27-APC, and anti–CD45RA-FITC for 30 min, washed, resuspended, and analyzed/sorted by flow cytometry.

Single-Cell Multiplex RT-PCR.

Single tetramer+CD8+CD4−CD14−CD19− cells were sorted using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) into 96-well plates. CDR3αβ regions were determined using a single-cell multiplex RT-PCR (28, 29). Sequences were analyzed with FinchTV, and V/J regions were identified by IMGT.

Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS).

PBMCs were stimulated with peptides for 10 d, and IAV-specific CTLs were quantified using IFN-γ/TNF-α ICS (12, 33). C1R-A*0201 cells, HLA-B*0702+ PBMCs, or C1R-B*3501 cells were used to present antigen. Mouse spleen and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells were stimulated with M158 (GILGFVFTL), PA46 (FMYSDFHFI), or NS122 (AIMDKKIIL) for 5 h (17).

HLA-A2.1 Transgenic HHD Mice and de Novo IAV Epitope Mutations.

HLA-A2.1 transgenic HHD mice were developed by François Lemonnier (37) and provided by the Pasteur Institute. Experiments were approved by the University of Melbourne Animal Ethics Experimentation Committee. Mice were lightly anesthetized and infected with 103 pfu HK (H3N2) virus intranasally. Viral RNA was extracted from lungs 15 d after infection and reverse transcribed to cDNA (17). The M1 region was amplified and sequenced.

Recombinant Influenza Viruses.

Influenza viruses with amino acid substitutions in the M158 peptide (M1-I2M, M1-F5L, M1-V6I, and M1-F7Y) were generated using reverse genetics and amplified in embryonated eggs (38).

Protein chemistry and structural biology are described in SI Methods.

SI Methods

Protein Expression, Purification, and Crystallization.

The JM22 TCR (21) was expressed, refolded, and purified using engineered disulfide linkages in the constant domains between the TCR alpha chain constant domain and TCR beta chain constant domain. The α- and β-chains were expressed separately as inclusion bodies and refolded as described (39). Soluble class I heterodimers of HLA-A*02:01 containing the M158 (GILGFVFTL), M1-L3W (GIWGFVFTL), M1-F5L (GILGLVFTL), or M1-G4E (GILEFVFTL) peptides were prepared as described (39). Crystals of the TCR–pHLA complex or pHLA individually in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl were grown by the hanging-drop, vapor-diffusion method at 20 °C with a protein/reservoir drop ratio of 1:1 at 5–10 mg/mL, in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.5), 70 mM NaCl, 16% PEG 10,000 and 14% glycerol or in 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 6.5) and 16% PEG 3350, respectively.

Data Collection and Structure Determination.

Data were collected on the MX1 and MX2 beamlines at the Australian Synchrotron, Clayton, VIC, Australia, using the ADSC-Quantum 210 and 315r CCD detectors, respectively (at 100 K). Data were processed using XDS software and were scaled using SCALA software from the CCP4 suite. The JM22 TCR structure was determined by molecular replacement using the PHASER program with the JM22 TCR as the search model for the TCR [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 2VLJ] (23), and the HLA-A*02:01 structure was determined using the HLA-A*02:01 without the peptide (PDB ID code 3GSO) (40). Manual model building was conducted using the Coot software followed by maximum-likelihood refinement with PHENIX and Buster programs. The TCR was numbered as per the original JM22 TCR structure (23). The final model has been validated using the Protein Database validation website, and the final refinement statistics are summarized in Tables S6 and S7. Coordinates were submitted to the PDB [ID codes 5HHQ (HLA-A*0201-M1-L3W); 5HHP (HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E); 5HHN (HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L); 5HHO (JM22-TCR-HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E); and 5HHM (JM22-TCR-HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L)]. All molecular graphics representations were created using PyMol.

Surface Plasmon Resonance Measurement and Analysis.

Surface plasmon resonance experiments were conducted at 25 °C on the BIAcore 3000 instrument with TBS buffer supplemented with 1% BSA [10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.005% surfactant P20]. The human TCR-specific monoclonal antibody 12H8 was coupled to research-grade CM5 chips with standard amine coupling. The experiment was conducted as previously described (39) with a concentration range up to 200 or 600 µM of the pHLA complexes. BIAevaluation version 3.1 was used for data analysis using the 1:1 Langmuir binding model. Experiments were carried out at least twice in duplicate (n ≥ 2).

Thermal Stability Assay.

A thermal shift assay was used to determine the stability of the pHLA complexes. The thermal stability assay was performed in the Real Time Detection system (Corbett Rotor-Gene 3000) using the fluorescent dye SYPRO orange to monitor protein unfolding. Each pHLA complex [5 and 10 μM in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl] was heated from 30 to 95 °C with a heating rate of 1 °C/min. The fluorescence intensity was measured with excitation at 530 nm and emission at 555 nm. Experiments were carried out in duplicate.

Statistical Analysis.

Significance was determined using an unpaired, two-tailed Student t test and assigned as #P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, and **P < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nicola Bird for technical assistance and Natalie Saunders for sorting. The C1R-B*3501 plasmid was provided by Dr. David Cole (Cardiff University). HLA-A2.1 transgenic HHD mice were developed and provided by Dr. François Lemonnier (Pasteur Institute). This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant 1042662 (to A.M., S.Y.C.T., and K.K.) and NHMRC Program Grant 567122 (to P.C.D. and K.K.). S.A.V. is an NHMRC Early Career Research Fellow, E.B.C. is an NHMRC Peter Doherty Fellow, D.A.P. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator, S.Y.C.T. and K.K. are NHMRC Career Development Fellows, J.R. is an NHMRC Australia Fellow (AF50), and S.G. is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow (FT120100416). E.J.G. is a recipient of an NHMRC Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research Scholarship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: Crystallography, atomic coordinates, and structure factors reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database [PDB ID codes 5HHQ (HLA-A*0201-M1-L3W), 5HHP (HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E), 5HHN (HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L), 5HHO (JM22-TCR-HLA-A*0201-M1-G4E), and 5HHM (JM22-TCR-HLA-A*0201-M1-F5L)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1603106113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Quiñones-Parra S, Loh L, Brown LE, Kedzierska K, Valkenburg SA. Universal immunity to influenza must outwit immune evasion. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:285. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sridhar S, et al. Cellular immune correlates of protection against symptomatic pandemic influenza. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1305–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm.3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, et al. Recovery from severe H7N9 disease is associated with diverse response mechanisms dominated by CD8⁺ T cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6833. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valkenburg SA, et al. Protective efficacy of cross-reactive CD8+ T cells recognising mutant viral epitopes depends on peptide-MHC-I structural interactions and T cell activation threshold. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(8):e1001039. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worobey M, Han GZ, Rambaut A. A synchronized global sweep of the internal genes of modern avian influenza virus. Nature. 2014;508(7495):254–257. doi: 10.1038/nature13016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMichael AJ, Gotch FM, Noble GR, Beare PA. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to influenza. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(1):13–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307073090103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreijtz JH, et al. Cross-recognition of avian H5N1 influenza virus by human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte populations directed to human influenza A virus. J Virol. 2008;82(11):5161–5166. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02694-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Sandt CE, et al. Human cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed to seasonal influenza A viruses cross-react with the newly emerging H7N9 virus. J Virol. 2014;88(3):1684–1693. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02843-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quiñones-Parra S, et al. Preexisting CD8+ T-cell immunity to the H7N9 influenza A virus varies across ethnicities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(3):1049–1054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322229111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boon AC, et al. Sequence variation in a newly identified HLA-B35-restricted epitope in the influenza A virus nucleoprotein associated with escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2002;76(5):2567–2572. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2567-2572.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkhoff EG, et al. A mutation in the HLA-B*2705-restricted NP383-391 epitope affects the human influenza A virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in vitro. J Virol. 2004;78(10):5216–5222. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5216-5222.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gras S, et al. Cross-reactive CD8+ T-cell immunity between the pandemic H1N1-2009 and H1N1-1918 influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(28):12599–12604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007270107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotch F, Rothbard J, Howland K, Townsend A, McMichael A. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize a fragment of influenza virus matrix protein in association with HLA-A2. Nature. 1987;326(6116):881–882. doi: 10.1038/326881a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assarsson E, et al. Immunomic analysis of the repertoire of T-cell specificities for influenza A virus in humans. J Virol. 2008;82(24):12241–12251. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01563-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu W, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes established by seasonal human influenza cross-react against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. J Virol. 2010;84(13):6527–6535. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00519-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berkhoff EG, et al. Functional constraints of influenza A virus epitopes limit escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2005;79(17):11239–11246. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11239-11246.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valkenburg SA, et al. Acute emergence and reversion of influenza A virus quasispecies within CD8+ T cell antigenic peptides. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2663. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon JJ, et al. Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity. 2007;27(2):203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moss PA, et al. Extensive conservation of alpha and beta chains of the human T-cell antigen receptor recognizing HLA-A2 and influenza A matrix peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(20):8987–8990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawson TM, et al. Influenza A antigen exposure selects dominant Vbeta17+ TCR in human CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses. Int Immunol. 2001;13(11):1373–1381. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.11.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart-Jones GB, McMichael AJ, Bell JI, Stuart DI, Jones EY. A structural basis for immunodominant human T cell receptor recognition. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(7):657–663. doi: 10.1038/ni942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naumov YN, et al. Multiple glycines in TCR alpha-chains determine clonally diverse nature of human T cell memory to influenza A virus. J Immunol. 2008;181(10):7407–7419. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishizuka J, et al. The structural dynamics and energetics of an immunodominant T cell receptor are programmed by its Vbeta domain. Immunity. 2008;28(2):171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossjohn J, et al. T cell antigen receptor recognition of antigen-presenting molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:169–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis MM. The problem of plain vanilla peptides. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(7):649–650. doi: 10.1038/ni0703-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messaoudi I, Guevara Patiño JA, Dyall R, LeMaoult J, Nikolich-Zugich J. Direct link between mhc polymorphism, T cell avidity, and diversity in immune defense. Science. 2002;298(5599):1797–1800. doi: 10.1126/science.1076064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price DA, et al. T cell receptor recognition motifs govern immune escape patterns in acute SIV infection. Immunity. 2004;21(6):793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang GC, Dash P, McCullers JA, Doherty PC, Thomas PG. T cell receptor αβ diversity inversely correlates with pathogen-specific antibody levels in human cytomegalovirus infection. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(128):128ra42. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen TH, et al. Recognition of distinct cross-reactive virus-specific CD8+ T cells reveals a unique TCR signature in a clinical setting. J Immunol. 2014;192(11):5039–5049. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flint SM, et al. Disproportionate impact of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza on Indigenous people in the Top End of Australia’s Northern Territory. Med J Aust. 2010;192(10):617–622. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clemens EB, et al. Towards identification of immune and genetic correlates of severe influenza disease in Indigenous Australians. Immunol Cell Biol November 17, 2015 doi: 10.1038/icb.2017.47. , 10.1038/icb.2015.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price DA, et al. Public clonotype usage identifies protective Gag-specific CD8+ T cell responses in SIV infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206(4):923–936. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valkenburg SA, et al. Immunity to seasonal and pandemic influenza A viruses. Microbes Infect. 2011;13(5):489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wahl A, et al. T-cell tolerance for variability in an HLA class I-presented influenza A virus epitope. J Virol. 2009;83(18):9206–9214. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00932-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macdonald WA, et al. T cell allorecognition via molecular mimicry. Immunity. 2009;31(6):897–908. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valkenburg SA, et al. Preemptive priming readily overcomes structure-based mechanisms of virus escape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(14):5570–5575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302935110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pascolo S, et al. HLA-A2.1-restricted education and cytolytic activity of CD8(+) T lymphocytes from beta2 microglobulin (beta2m) HLA-A2.1 monochain transgenic H-2Db beta2m double knockout mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185(12):2043–2051. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kedzierska K, et al. Complete modification of TCR specificity and repertoire selection does not perturb a CD8+ T cell immunodominance hierarchy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(49):19408–19413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810274105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gras S, et al. The shaping of T cell receptor recognition by self-tolerance. Immunity. 2009;30(2):193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gras S, et al. Structural bases for the affinity-driven selection of a public TCR against a dominant human cytomegalovirus epitope. J Immunol. 2009;183(1):430–437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]