Significance

Cysteine fatty acylation (S-fatty acylation) regulates the stability, trafficking, and activity of proteins in eukaryotes. Current methods to study S-fatty acylation rely on the metabolic incorporation of fatty acid analogs or selective chemical labeling and affinity purification, which limits the detection of endogenous S-fatty acylated protein isoforms and levels. Here we demonstrate that the biochemical exchange of acyl groups on cysteines with defined mass-tags enables the direct visualization of endogenous S-fatty acylated protein levels. The application of this mass-tag labeling method revealed that site-specific S-fatty acylation of interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 controls the antiviral activity of this IFN-induced effector.

Keywords: fatty-acylation, palmitoylation, PEGylation, influenza virus, IFITM3

Abstract

Fatty acylation of cysteine residues provides spatial and temporal control of protein function in cells and regulates important biological pathways in eukaryotes. Although recent methods have improved the detection and proteomic analysis of cysteine fatty (S-fatty) acylated proteins, understanding how specific sites and quantitative levels of this posttranslational modification modulate cellular pathways are still challenging. To analyze the endogenous levels of protein S-fatty acylation in cells, we developed a mass-tag labeling method based on hydroxylamine-sensitivity of thioesters and selective maleimide-modification of cysteines, termed acyl-PEG exchange (APE). We demonstrate that APE enables sensitive detection of protein S-acylation levels and is broadly applicable to different classes of S-palmitoylated membrane proteins. Using APE, we show that endogenous interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 is S-fatty acylated on three cysteine residues and site-specific modification of highly conserved cysteines are crucial for the antiviral activity of this IFN-stimulated immune effector. APE therefore provides a general and sensitive method for analyzing the endogenous levels of protein S-fatty acylation and should facilitate quantitative studies of this regulated and dynamic lipid modification in biological systems.

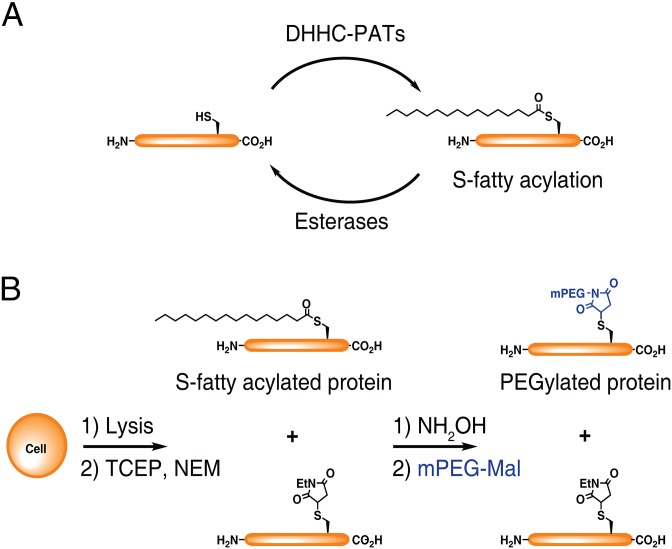

Protein S-fatty acylation describes the covalent attachment of long-chain fatty acids to cysteine (Cys) residues through a thioester bond, which alters the hydrophobicity of diverse proteins and regulates their stability, trafficking, and activity in eukaryotic cells (Fig. 1A) (1, 2). Cys residues are predominately acylated with palmitic acid (S-palmitoylation), but can also be modified with longer chain and unsaturated fatty acids, thus more generally described as S-fatty acylation (1, 3, 4). The fatty-acylation of Cys residues is regulated by the DHHC-family of protein acyltransferases (5, 6) and different classes of thioesterases (7, 8) that are associated with a variety of important physiological pathways and diseases (1). Determining the precise levels of protein S-fatty acylation is therefore crucial for understanding how this dynamic lipid modification is regulated and quantitatively controls specific cellular pathways.

Fig. 1.

Mass-tag analysis of protein S-fatty acylation. (A) S-fatty acylation controls the trafficking, stability, and function of membrane proteins and are regulated by DHHC-protein acyltransferases (DHHC-PATs), and esterases. (B) With APE, cell lysates are reduced with TCEP, and then free cysteine residues are capped with NEM. S-fatty acid groups are removed by NH2OH, and the exposed cysteines are reacted with mPEG-Mal. Proteins are separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by Western blot, enabling the detection of both unmodified and S-fatty acylated proteins.

Recent methods to detect and enrich S-fatty acylated proteins have facilitated the characterization of key regulatory mechanisms and discovery of new S-fatty acylated proteins (1, 2). For example, alkyne-modified fatty acid chemical reporters have enabled the fluorescent detection and enrichment of metabolically labeled proteins using bioorthogonal ligation methods (Fig. S1A) (9, 10). Alternatively, exploitation of thioester sensitivity to hydroxylamine (NH2OH) has enabled selective capture and analysis of S-acylated proteins by acyl-biotin exchange (ABE) (Fig. S1B) (11, 12) or acyl-resin capture (acyl-RAC) (Fig. S1C) (13). However, all of these methods do not readily reveal the fraction of unmodified versus S-fatty acylated proteins or the number of sites of S-acylation, which are both crucial for understanding how quantitative differences in S-fatty acylation control protein function and associated cellular phenotypes.

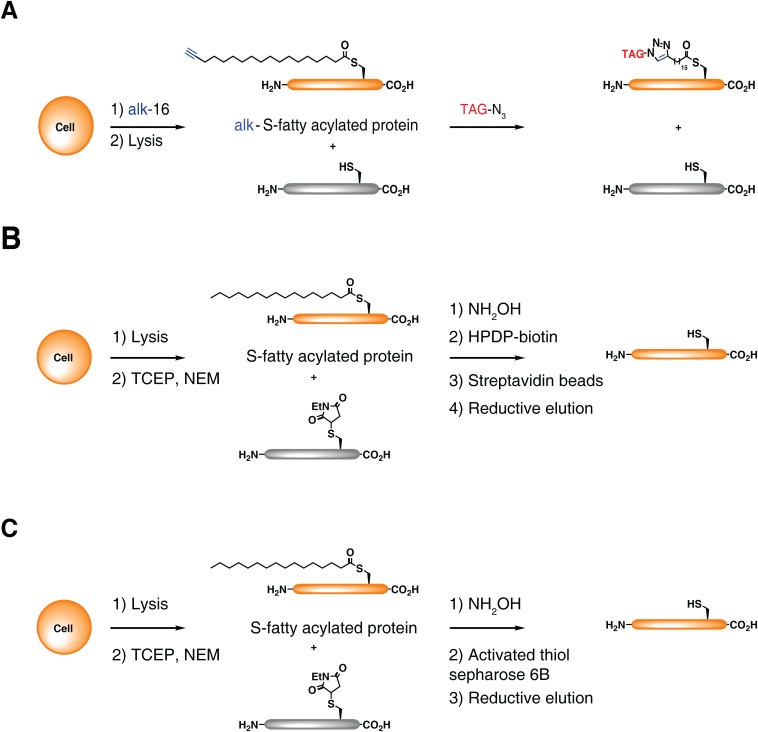

Fig. S1.

Methods for protein S-fatty acylation analysis. (A) For metabolic labeling, cells are incubated with alkyne-labeled palmitate (alk-16). Proteins are reacted with an azide-functionalized reagents by CuAAC and analyzed by in-gel fluorescence, as previously described (1). (B) For ABE, cell lysates are reduced with TCEP, cysteines labeled with NEM. Thioesters are then cleaved with NH2OH and newly generated cysteines are reacted with HPDP-Biotin, as previously described (2). Following streptavidin bead enrichment, selectively captured proteins are then eluted with reducing agents and then analyzed by Western blot. (C) In acyl-RAC exchange, cell lysates are prepared similarly to ABE but reacted with activated thiol-Sepharose beads, instead of HPDP-Biotin. Selectively captured proteins are then eluted with reducing agents and then analyzed by Western blot.

To evaluate endogenous levels of S-fatty acylation, we developed a mass-tag labeling method termed acyl-PEG exchange (APE) that exploits the NH2OH-sensitivity of thioesters and selective reactivity of Cys residues for site-specific alkylation with maleimide-functionalized polyethylene glycol reagents (Fig. 1B). APE induces a mobility-shift on S-acylated proteins that can be readily monitored by Western blot of target proteins and circumvents the need for metabolic labeling or affinity enrichment of proteins. We demonstrate that APE can reveal endogenous levels, stoichiometry and specific sites of S-acylation on diverse S-palmitoylated proteins. Using APE, we characterized the endogenous levels of interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) S-fatty acylation and show that site-specific modifications of highly conserved Cys residues are crucial for the antiviral activity of this key IFN-induced immune effector. APE provides a sensitive and readily accessible method for evaluating endogenous S-fatty acylation levels and should facilitate the quantitative analysis of this dynamic lipid modification in diverse cell types and tissues.

Results

APE Enables Direct Visualization of S-Acylated Protein Isoforms.

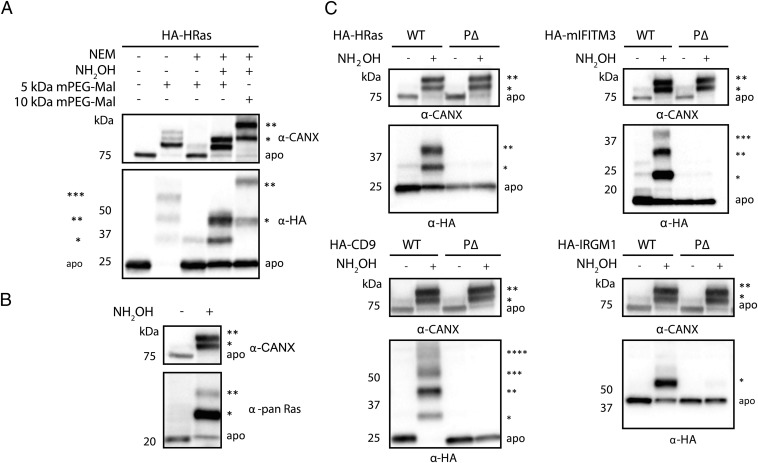

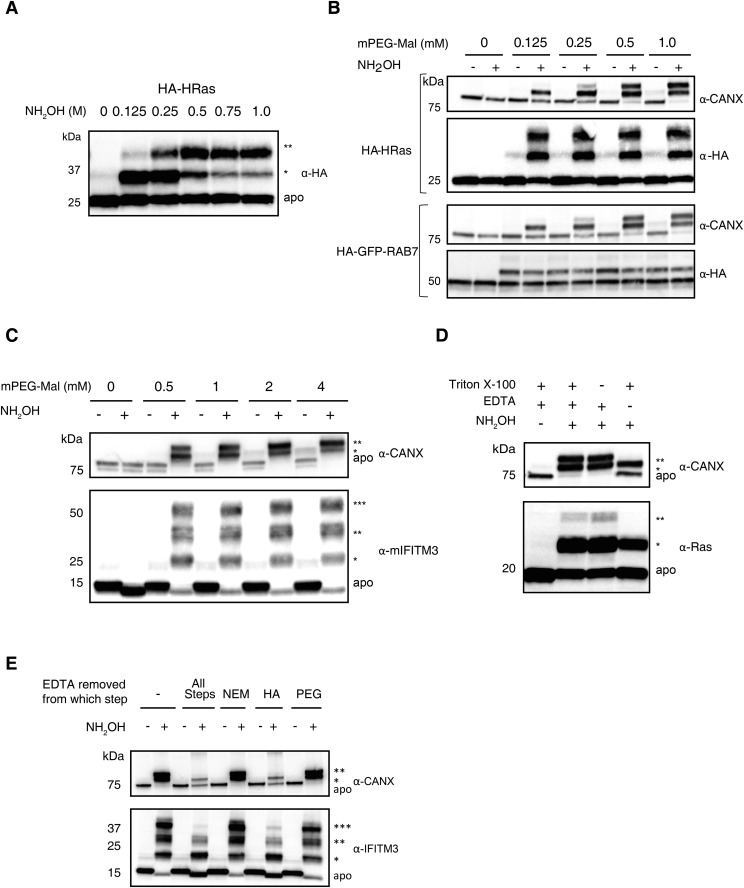

To establish the utility of APE, we first analyzed HRas, a well-characterized S-palmitoylated protein. HRas contains one farnesylation site at Cys-186 and two S-palmitoylation sites at Cys-181 and 184, which regulate the trafficking and activity of this small GTPase at the plasma membrane and internal membrane compartments (14). To explore mass-shift detection by APE, HEK293T cells were transfected with N-terminally HA-tagged HRas (HA-HRas) and lysed with SDS-containing buffer. Lysates were reacted with Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to reduce and block free Cys residues. Proteins were then treated with NH2OH to cleave thioesters, alkylated with methoxy-PEG-maleimide (mPEG-Mal), and analyzed by Western blot (Fig. 2A). Reaction of cell lysates with 5 kDa mPEG-Mal alone revealed three slower migrating HRas species, consistent with three unmodified Cys residues at positions 51, 80, and 118 on HRas that were blocked by pretreatment with NEM (lanes 1–3, Fig. 2A). Cleavage of thioesters with NH2OH followed by mPEG-Mal alkylation resulted in unmodified polypeptide at 25 kDa (apo) and two slower migrating polypeptides, which corresponded to mono-PEGylated (*) and di-PEGylated (**) proteins (lane 4, Fig. 2A). Reaction of cell lysates with 10 kDa mPEG-Mal induced a mass shift approximately twice that observed for the 5 kDa reagent, consistent with site-specific PEGylation (lane 5, Fig. 2A). The NH2OH-dependent PEGylation-induced mass shift correlates with the two predicted sites of S-palmitoylation on HRas (14). In parallel, we also analyzed endogenous calnexin (CANX), a type I integral membrane protein with two S-palmitoylation sites (15, 16), which yielded mono- and di-PEGylated polypeptides, suggesting CANX is fully S-acylated under these conditions (Fig. 2A). To optimize APE detection of S-acylated proteins, we tested varying concentrations of NH2OH and mPEG-Mal for selective thioester cleavage and Cys alkylation of proteins, respectively. We determined that 0.75 M NH2OH treatment for 1 h and 1 mM mPEG-Mal labeling for 2 h was optimal for APE detection of transfected HA-HRas and endogenous CANX, which provides a useful protein loading control for APE (Fig. S2 A and B). Increasing concentrations of mPEG-Mal can result in nonspecific alkylation, as seen for CANX in samples not treated with NH2OH (Fig. S2C). Rab7, a prenylated GTPase that is not S-palmitoylated (17), was also analyzed and did not exhibit NH2OH-dependent PEGylation (Fig. S2B), despite the presence of multiple Cys residues, confirming the specificity of the APE protocol for S-acylated proteins. To further characterize our protocol for APE, we evaluated the effect of Triton X-100 and EDTA in the lysis and reaction buffers. Although additional Triton X-100 was not necessary to further solubilize proteins in SDS-containing lysis buffer, EDTA was required for complete NH2OH-dependent PEGylation of CANX, HRas, and IFITM3 (Fig. S2 D and E). The addition of EDTA was particularly crucial during the NH2OH-treatment step of cell lysates, which likely chelates metals involved in oxidation of the newly liberated Cys residues that would interfere with subsequent PEGylation (Fig. S2 D and E). Using this optimized APE protocol, a pan-Ras antibody readily detected the endogenous levels of mono- and di-S-fatty acylated Ras in HeLa cells (Fig. 2B), showing that the APE can reveal S-fatty acylation levels of other endogenously expressed proteins in addition to abundant proteins such as CANX.

Fig. 2.

APE enables robust detection of protein S-fatty acylation levels. (A) HEK293T transfected with HA-HRas were lysed and total cell lysates were subjected to APE with NEM (25 mM), NH-2OH (0.75 M), and mPEG-Mal (1 mM), and compared with negative controls. Samples were analyzed by Western blot using anti-HA and anti-CANX antibodies. The number of PEGylation events are indicated by asterisks (*). Apo refers to non-PEGylated protein. (B) HeLa cells were subjected to APE and endogenous Ras palmitoylation measured by Western blot with a pan-Ras antibody. (C) HEK293T cells expressing HA-tagged WT or palmitoylation-deficient (P△) constructs (HRas C181,184S; IRGM1 C371, -373, -374, -375A; mIFITM3 C71, -72, -105A; CD9 C9, -78, -79, -87, -218, -219A) of known S-palmitoylated proteins were analyzed with the APE. Representative of multiple experiments for all constructs.

Fig. S2.

Optimization of APE conditions. HEK293T cells overexpressing wild-type HA-HRas were analyzed with the APE, with different concentrations of (A) NH2OH, with 1-h incubation, and (B) 5 kDa mPEG-Mal with 2-h incubation. HA-GFP-Rab7, a prenylated endosome membrane marker demonstrates a NH2OH independent mass shift, emphasizing the importance of NH2OH controls for initial optimization. The number of PEGylation events are indicated by asterisks (*). (C) To ensure the complete mass shift of CANX and IFITM3, a higher range of mPEG-Mal concentrations were titrated with 2-h incubation. (D) Alkylation with mPEG-Mal without 0.2% Triton X-100 or EDTA reveals that, EDTA but not the detergent is essential for completion of the di-PEGylation (**) for both CANX and Ras. (E) EDTA is critical during treatment with NH2OH. HEK293T cells were analyzed by APE, and EDTA removed from individual stages of the protocol.

We next compared our APE protocol with other protein S-acylation detection methods. In comparison with ABE (11, 12) or acyl-RAC (13) (Fig. S1 B and C), APE enables the direct visualization of the different S-acylated isoforms of endogenously expressed CANX and Ras. APE also circumvents the need for affinity enrichment of proteins required for ABE and acyl-RAC, which can yield incomplete recovery of membrane-associated proteins and confound estimates of S-acylated and unmodified protein levels (Fig. S3A). With respect to the PEG-switch assay (PSA) (18), the reported conditions showed incomplete NH2OH-dependent PEGylation of CANX, Ras, and IFITM3 (lanes 2 and 8, Fig. S3B). In the PSA protocol, 2 mM mPEG-Mal was added together with 200 mM NH2OH, which could react with the maleimide group and affect the efficiency of PEGylation. We therefore separated the NH2OH treatment and mPEG-Mal labeling steps by removing excess NH2OH with chloroform-methanol precipitation. Separating the NH2OH-mediated deacylation and maleimide alkylation reactions restored the PEGylation efficiency to levels similar to our APE conditions (lane 6, Fig. S3B). Coincubation of NH2OH and mPEG-Mal in our APE protocol also significantly reduced the efficiency of PEGylation (lane 4, Fig. S3B), confirming the need to separate these steps for optimal mass shift analysis. To further determine the specificity and utility of our APE protocol, we analyzed several different classes of S-palmitoyated proteins in parallel with CANX, which provides an important S-fatty acylated protein loading control that typically yields ∼1:1 ratio of mono- and di-S-acylated polypeptides with our optimized APE conditions. In addition to dually lipidated cell signaling factors such as HRas, APE can readily reveal the S-fatty acylation isoforms and levels of other small GTPases (IRGM1) (19), multiple-pass membrane proteins (CD9) (20), as well as IFITM3 (21, 22) (Fig. 2C). The analysis of reported S-palmitoylation–deficient Cys mutants for these proteins confirms their sites of modification and shows the levels of S-fatty acylated isoforms when expressed in HEK293T cells. These results suggest our optimized NH2OH-mediated acyl-PEGylation exchange protocol, which separates Cys deacylation and PEGylation steps, provides a robust and general method to evaluate protein S-acylation levels.

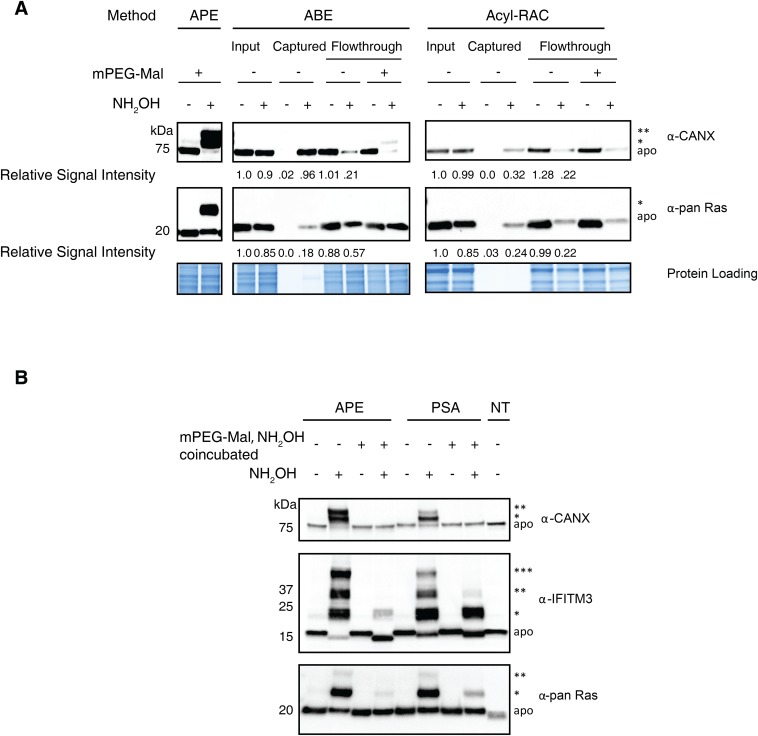

Fig. S3.

Comparison of NH2OH-mediated protein S-acylation detection methods. (A) Aliquots from the same Raw264.7 macrophage lysate were analyzed with the APE, ABE, and the acyl-RAC assay; representative of triplicate. Flow-through was further incubated with mPEG-mal to detect if ABE or acyl-RAC failed to enrich a portion of S-acylated proteins. (B) Comparison of APE with PSA in HEK293T cells. To test whether NH2OH interferes with the cysteine labeling of mPEG-Mal, NH2OH was incubated either separately, or together with mPEG-Mal (as described in the PSA protocol) for the duration of the reported mPEG-Mal incubation. The number of PEGylation events are indicated by asterisks (*). NT, not treated. Completion of APE is dependent on separation of thioester cleavage from PEGylation and inclusion of EDTA. PSA was performed as described, unless otherwise noted (3).

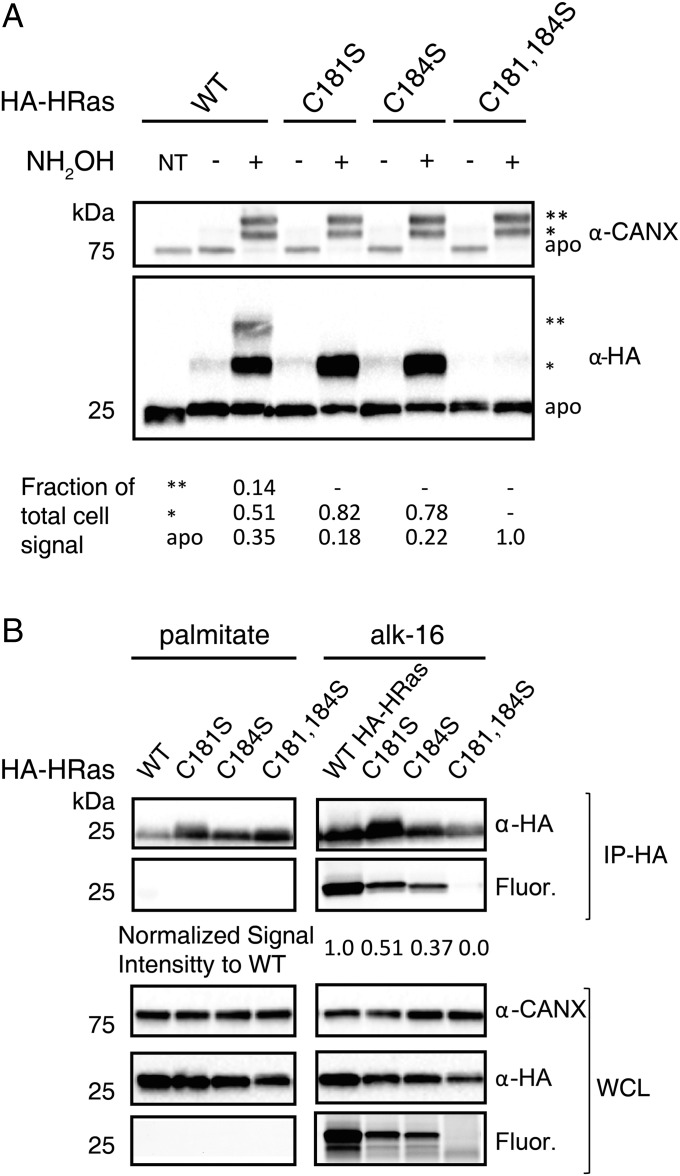

APE shows S-acylated protein isoforms and their relative levels but does not reveal whether specific proteins are directly fatty acid-modified or the dynamics of modifications at specific sites. Indeed, other S-acylated proteins in mammalian cells (e.g., enzymes, involved in ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like protein modification) (23), also contain thioester intermediates that could be subject to NH2OH-mediated PEGylation. To characterize protein S-acylation levels relative to fatty acid incorporation, we directly compared HRas S-fatty acylation by APE (Fig. 1B) and metabolic labeling (Fig. S1A). HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-HRas constructs, pulse-labeled with an alkyne-palmitic acid chemical reporter (alk-16), lysed, and analyzed by APE or subjected to bioorthogonal reaction with azide-rhodamine and in-gel fluorescence detection (Fig. 3). APE analysis of HA-HRas showed three α-HA reactive polypeptides corresponding to ∼0.35 unmodified (apo), 0.51 mono-PEGylated (*) and 0.14 di-PEGylated (**) species (Fig. 3A). The single Cys mutants (C181S, C184S) revealed ∼0.20 unmodified and 0.80 mono-PEGylated species, and as expected, the double Cys mutant (C181S, C184S) revealed only unmodified HA-HRas at 25 kDa (Fig. 3A). These results show that mutation of individual S-fatty acylation sites still afforded significant levels, ∼80%, of mono-S-acylated HRas (Fig. 3A). In contrast, metabolic labeling with alk-16 and in-gel fluorescence detection showed at least 50% decrease in labeling of single Cys mutants of HA-HRas (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that mono-S-fatty acylated HA-HRas is relatively stable, whereas dual S-fatty acylation is more dynamically regulated, which is consistent with previous studies of HRas fatty acylation, localization, and activity (14). This direct comparison highlights the utility of monitoring protein S-fatty acylation with both APE and metabolic labeling, which reveals the relative levels of unmodified and S-fatty acylated protein isoforms as well as site-specific differences in dynamic S-fatty acylation.

Fig. 3.

APE reveals site-specific S-fatty acylation levels. (A) HEK293T cells transfected with HA-HRas wild-type or cysteine mutants were labeled for 2 h with 50 μM alk-16 in DMEM containing charcoal-dextran–treated FBS. Samples were lysed, subjected to APE, separated by SDS/PAGE, and analyzed by Western blot. NT refers to nontreated control. The number of PEGylation events are indicated by asterisks (*). (B) Samples from the same cell lysate as in A were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA agarose-beads, and reacted with azide-rhodamine (az-rho) by Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). Whole-cell lysate (WCL) was reacted with az-rho by CuAAC and included for comparison. Samples were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by in-gel fluorescence and Western blot.

IFITM3 Antiviral Activity Is Controlled by Specific S-Fatty Acylation Sites and Levels.

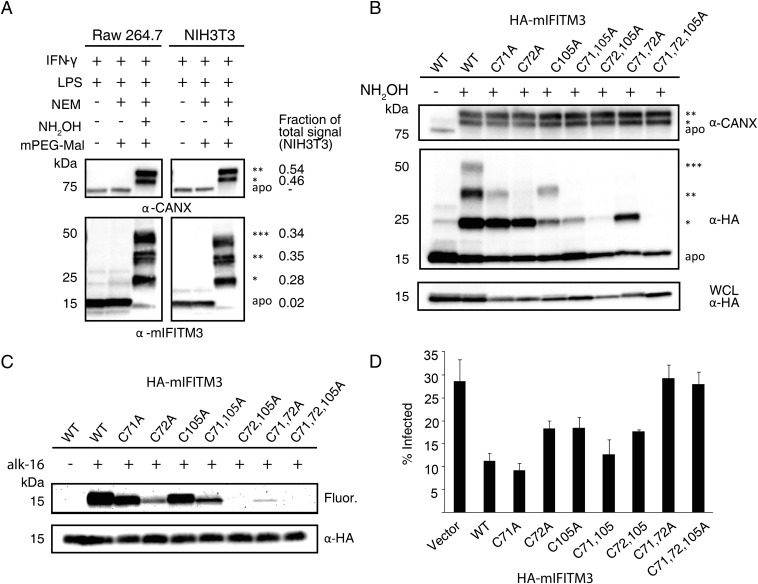

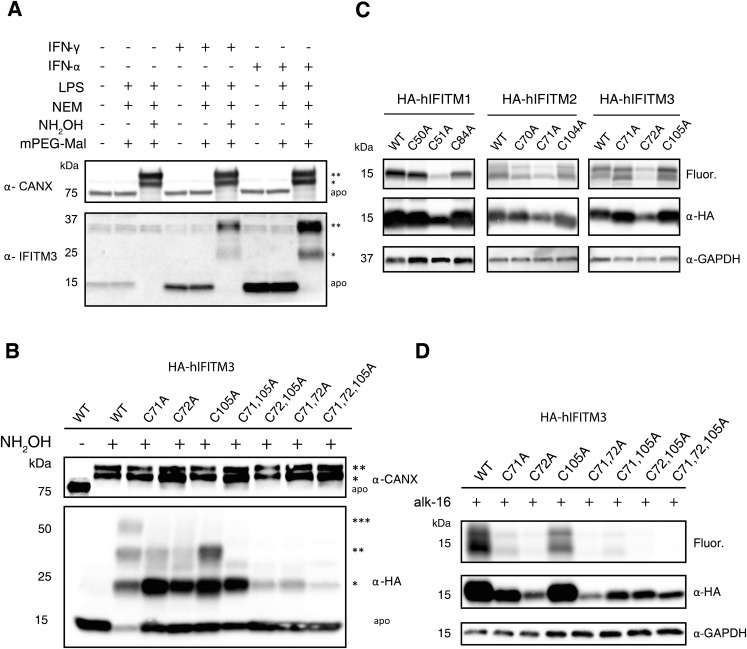

We next focused on sites and levels of IFITM3 S-fatty acylation, which was discovered by our laboratory from alk-16 metabolic labeling and proteomic studies (21, 22). Our initial studies demonstrated that the mutation of all three Cys residues (71, 72, and 105) to alanine (Ala) in murine IFITM3 abrogated S-fatty acylation and decreased antiviral activity (21, 22). However, the endogenous levels of IFITM3 S-fatty acylation and specific sites of modification have not been characterized directly. APE analysis of endogenously expressed IFITM3 in IFN/LPS-stimulated murine NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and Raw264.7 macrophages revealed three slower migrating PEGylated polypeptides that correspond to the mono, di-, and tri-S-fatty acylated isoforms of mIFITM3 (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4A). Similar APE results were also observed for human IFITM3 in IFN-stimulated A549 lung epithelial cells (Fig. S5A), demonstrating that the majority, if not all, of endogenously expressed IFITM3 in IFN-stimulated cells is S-fatty acylated on at least one Cys residue. To evaluate the contribution of individual Cys residues on IFITM3 S-fatty acylation, we generated single and double Cys mutants and analyzed their levels of S-fatty acylation by APE and metabolic labeling. APE analysis of the wild-type and the individual Cys to Ala HA-mIFITM3 mutants transfected into unstimulated murine NIH 3T3 fibroblasts showed that mutation of Cys71 and 105 to Ala eliminated the tri-S-acylated fraction and decreased the levels of the mono- and di-S-acylated mIFITM3 (Fig. 4B and Fig. S4B). In contrast, the C72A mutant or multiple Cys mutants abrogated the tri- and di-S-acylated IFITM3 and even lost the mono-S-acylated fraction for the C72,105A mutant (Fig. 4B). Similar APE results were also observed with human IFITM3 constructs expressed in HEK293T cells (Fig. S5B). Metabolic labeling of these HA-mIFITM3 Cys mutants with alk-16 and in-gel fluorescence detection also revealed C72 is the major site of S-fatty acylation in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (Fig. 4C) and HEK293T cells (Fig. S4C). C72 is highly conserved among IFITM isoforms (24, 25) and is also a key site of S-fatty acylation for human IFITM1, -2, and -3 (Fig. S5C). The comparison of APE and alk-16 labeling suggests that, although the C72A IFITM3 mutant is still significantly mono-S-fatty acylated (Fig. 4B and Figs. S4B and S5B), the majority of fatty acid metabolic labeling is abrogated (Fig. 4C and Figs. S4C and S5C). These results demonstrate that, similar to HRas (Fig. 3), mono-S-fatty acylation of IFITM3 is relatively stable but dual S-fatty acylation is more dynamically regulated.

Fig. 4.

Murine IFITM3 S-fatty acylation levels, sites of modification and antiviral activity. (A) NIH 3T3 or Raw264.7 macrophages were activated with 500 ng/mL LPS, 100 U/mL IFN-γ for 16 h, subjected to APE, and analyzed by Western blot. (B) NIH 3T3 cells transfected with WT HA-mIFITM3, or Cys to Ala mutant constructs were subjected to APE and analyzed by Western blot. The number of PEGylation events are indicated by asterisks (*). Analysis of whole-cell lysate (WCL) indicates levels of protein expression without APE. (C) NIH 3T3 cells transfected with HA-mIFITM3 constructs were metabolically labeled for 2 h with 50 μM alk-16. Cell lysates prepared with 1% Brij 97 were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA agarose-beads, reacted with az-rho by CuAAC, separated by SDS/PAGE, and visualized by fluorescence gel scanning. Comparable protein loading was confirmed by anti-HA Western blotting. (D) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with HA-mIFITM3 constructs, followed by infection with PR8 influenza virus at a multiplicity of infection of 5 for 18 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with anti-influenza NP antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. Graph shows anti-influenza NP+ cells for each condition; average of triplicate. Error bar represents SEM, n = 3.

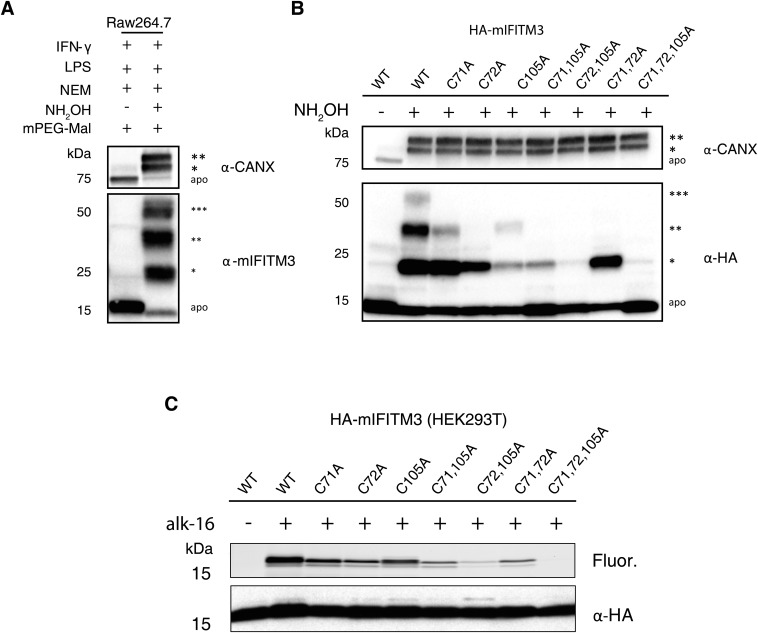

Fig. S4.

S-acylation level of endogenous and overexpressed mIFITM3. (A) Biological replicate of Fig. 4A. Macrophages were subjected to APE and analyzed by Western blot for endogenous IFITM3. (B) Biological replicate of Fig. 4B, where NIH 3T3 cells overexpressing wild-type HA-mIFITM3 or cysteine to alanine mutant constructs were analyzed with the APE. The number of PEGylation events are indicated by asterisks (*). (C) HEK293T cells overexpressing wild-type mIFITM3 or cysteine mutants were metabolically labeled for 2 h with 50 µM alk-16. Cell lysates prepared with 1% Brij 97 were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA beads, reacted with az-rho by CuAAC, separated by SDS/PAGE and visualized by fluorescence gel scanning. Protein loading was confirmed by anti-HA Western blotting.

Fig. S5.

Fatty-acylation of human IFITM3 cysteine mutant constructs. (A) A549 cells were activated with 500 ng/mL LPS, 100 μg/mL IFN-γ, or IFN-α for 16 h, subjected to APE, separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by Western blot. A third mass shift was not detected. (B) HA-hIFITM3 constructs were transfected in HEK293T cells, subjected to APE, and analyzed by Western blot. The number of PEGylation events are indicated by asterisks (*). (C) HEK293T cells expressing wild-type, or cysteine mutant human IFITM 1–3 were metabolically labeled with 50 µM alk-16. Cell lysates prepared with 1% Brij 97 were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA beads, reacted with az-rho, and analyzed in-gel fluorescence. (D) HEK293T cells expressing wild-type or cysteine mutant human IFITM3 were metabolically labeled for 2 h with 50 µM alk-16. Cell lysates prepared with 1% Brij 97 were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA beads, reacted with az-rho and analyzed by in-gel fluorescence. Protein loading was confirmed by anti-HA Western blotting.

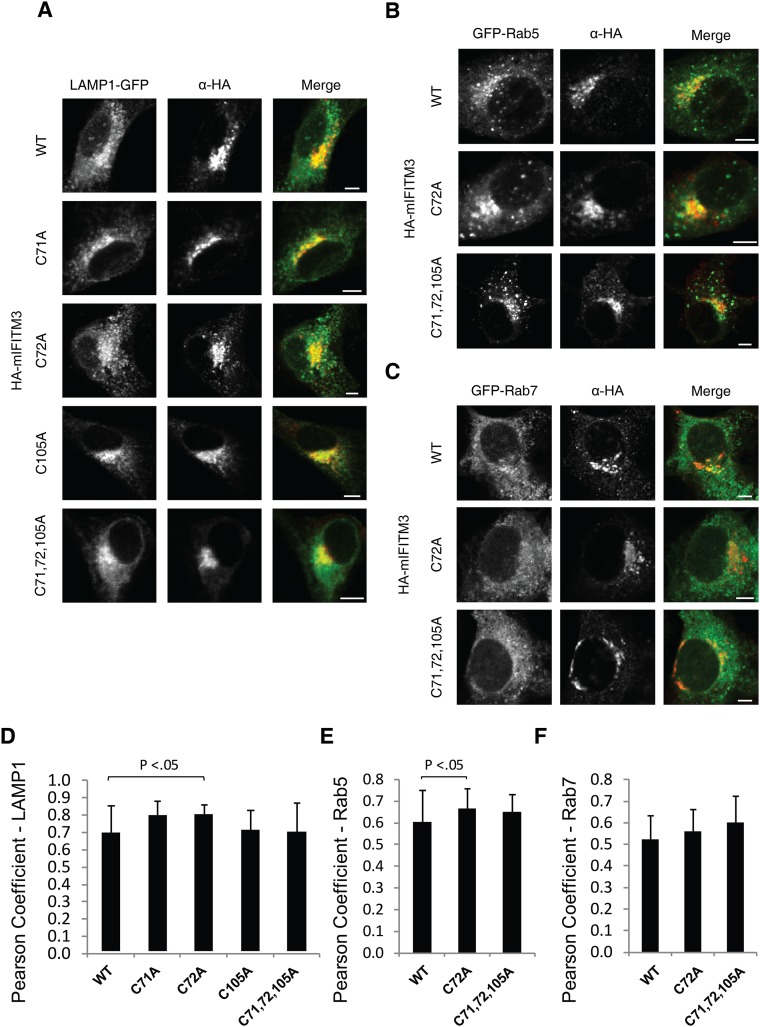

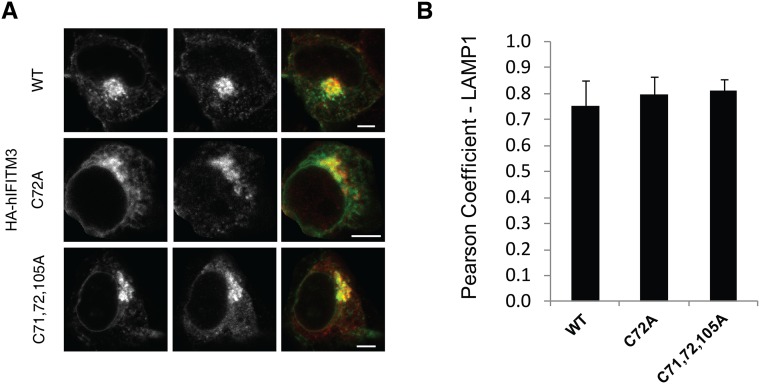

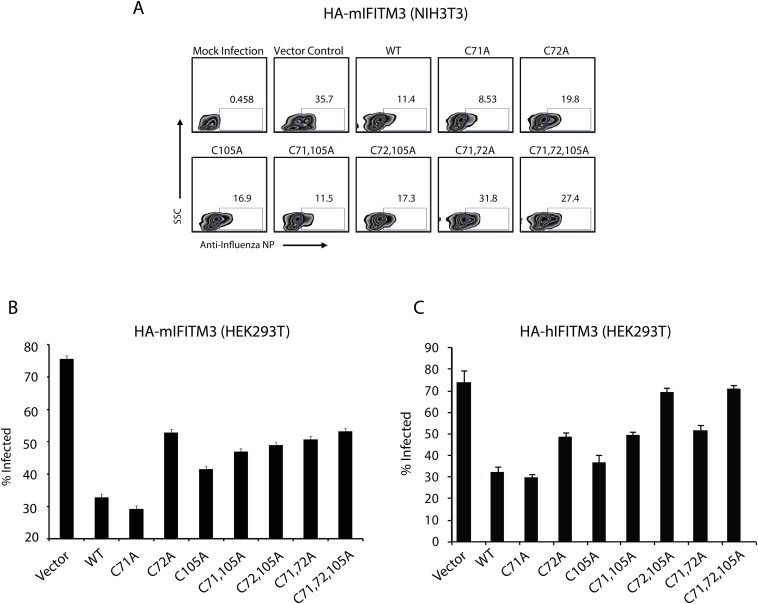

To determine the functional significance of site-specific IFITM3 S-fatty acylation, we evaluated the cellular localization and antiviral activity of these IFITM3 Cys mutants. Consistent with previous overexpression and immunofluorescence studies (21, 26, 27), the majority of wild-type HA-mIFITM3 constructs colocalized with lysosomes marked by LAMP1-GFP in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (Fig. S6A). A minor fraction of HA-mIFITM3 also colocalized with GFP-Rab5 and Rab7-labeled endocytic vesicles (Fig. S6 C and B). Despite their differences in protein S-fatty acylation levels (Fig. 4), mIFITM3 Cys mutants showed similar cellular distribution in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts by quantitative immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. S6 A–D). Similar cellular distribution was also observed for the wild-type and HA-hIFITM3 Cys mutants in HEK293T cells (Fig. S7). Nonetheless, these IFITM3 Cys mutants exhibited site-specific effects on antiviral activity against influenza virus infection (Fig. 4D and Fig. S8). To evaluate the site-specific effects of S-fatty acylation on IFITM3 antiviral activity, unstimulated NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with the HA-mIFITM3 constructs, then infected with influenza virus (PR8) and the percentage of infected cells was quantified by anti-influenza nuclear protein (NP) staining using flow cytometry, as previously described (21, 22). Our results show that the C71A mutation does not significantly impair HA-mIFITM3 antiviral activity compared with wild-type, whereas C72A and C105A mutants show ∼50% decrease in antiviral activity (Fig. 4D and Fig. S8A). The double Cys mutants of mIFITM3 also exhibited diminished antiviral activity, with the C71,72A mutant showing loss of antiviral activity comparable to the S-fatty acylation-deficient C71,72,105A mutant (Fig. 4D and Fig. S8A). Similar antiviral activity for the murine and human IFITM3 Cys mutants were observed in HEK293T cells (Fig. S8 B and C). These results demonstrate that, whereas site-specific differences in S-fatty acylation do not significantly affect IFITM3 cellular distribution upon overexpression, the lower levels of S-fatty acylation at specific Cys residues decrease IFITM3 antiviral activity.

Fig. S6.

Immunofluorescence analysis of mIFITM3 localization. (A–C) NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with HA-mIFITM3 and (A) lysosomal marker LAMP1-GFP, (B) early endosome marker GFP-Rab5, and (C) late endosome marker GFP-Rab7. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (D–F) Quantification of HA-mIFITM3 colocalization using Pearson coefficient. Sample sizes per condition are: (D) n = 10, (E) n = 20, and (F) n = 20. Error bar represent SD.

Fig. S7.

Immunofluorescence analysis of hIFITM3 localization. (A and B) HEK293T cells were transfected with LAMP1-GFP, and HA-hIFITM3 WT, C72A, or S-palmitoylation deficient (C71, 72, 105A) constructs. Cells were fixed and stained with primary anti-HA antibody, Alexa-647 secondary antibody, and imaged with a Zeiss confocal microscope. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (B) Quantification of HA-hIFITM3 colocalization using Pearson coefficient was done using Imaris software. n = 20 cells per condition. Error bar represents SD.

Fig. S8.

Antiviral activity of HA-tagged IFITM3 constructs (A) Example of flow cytometry data of antiviral activity of overexpressed murine IFITM3 cysteine mutants. NIH 3T3 cells transfected overnight with wild-type, and cysteine mutant constructs of HA-mIFITM3, followed by infection with PR8 influenza virus at an MOI of 5 for 18 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and labeled with anti-HA and anti-influenza NP antibodies expressed in HEK293T cells. (B) HEK293T cells transfected overnight with wild-type, and cysteine mutant constructs of HA-mIFITM3, followed by infection with PR8 influenza virus at an MOI of 5 for 18 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and stained with anti-influenza NP antibodies. Graph of influenza-NP+ cells for each condition. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3. (C) HEK293T cells transfected overnight with wild-type, and cysteine mutant constructs of HA-human IFITM3, followed by infection with PR8 influenza virus at an MOI of 5 for 18 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with anti-influenza NP antibodies. Graph of influenza-NP+ cells for each condition. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3.

Discussion and Conclusion

The functional roles of protein S-fatty acylation in eukaryotes are expanding from proteomic studies and characterization of regulatory enzymes (1, 2). To understand the biological significance of protein S-fatty acylation in diverse biological pathways and disease, robust methods are needed for quantifying S-fatty acylated protein isoforms and levels. Inspired by mass shift-based assays for evaluating membrane topology of proteins (28), oxidation of Cys residues (29), and protein glycosylation (30, 31), we demonstrate that the NH2OH-mediated APE provides a sensitive and readily accessible method for determining the S-acylation levels of specific proteins that is not possible by previously reported methods using metabolic labeling or affinity enrichment (Fig. 1B). APE enables the direct visualization of overexpressed and endogenous levels of S-acylated protein isoforms by Western blot analysis and is broadly applicable to different classes of S-fatty acylated proteins (Fig. 2). The combination of APE and metabolic labeling provides complementary methods to visualize different isoforms as well as the levels and dynamics of S-fatty acylation (Fig. 3).

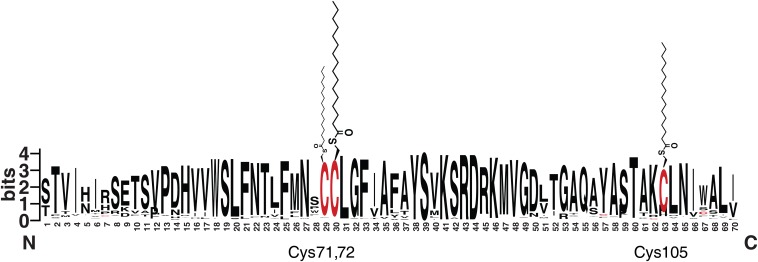

Using APE we demonstrate that endogenous IFITM3 is mostly S-fatty acylated in IFN-stimulated cells and that S-fatty acylation of specific Cys residues and levels are crucial for IFITM3 antiviral activity against influenza virus. The bioinformatic analysis of IFITM isoforms in diverse vertebrates shows that these three S-fatty acylated Cys residues (C71, -72, and -105 in mIFITM3) are highly conserved within this family of membrane proteins (Fig. S9) (24, 25). Notably, our APE analysis and fatty acid metabolic labeling show, to our knowledge for the first time, that the majority of endogenous IFITM3 is S-fatty acylated in IFN-stimulated cells and Cys72 is the most prominent S-fatty acylation site (Fig. 4). Although previous studies have suggested that mutation of these conserved Cys residues may partially affect the localization or trafficking of IFITMs in mammalian cells (21, 22, 27, 32), our quantitative immunofluorescence analysis suggest that site-specific S-fatty acylation may regulate more subtle functions of IFITM3 beyond lysosomal targeting (Figs. S7 and S8), such as protein–protein interactions (33, 34) or membrane tethering, but which awaits more detailed biochemical or biophysical studies. Nonetheless, these differences in site-specific S-fatty acylation have significant effects on IFITM3 antiviral activity. In murine and human IFITM3, even though Cys71 is highly conserved, this residue is dispensable for dual S-fatty acylation and antiviral activity (Fig. 4). In contrast, Cys72 in IFITM3 is the most prominent site of S-fatty acylation and results in the loss of antiviral activity when mutated to Ala (Fig. 4 and Figs. S5 and S6). The S-fatty acylation and antiviral activity of Cys105 may depend on the IFITM isoform, expression levels and cell-type, as the mutation of this Cys residue decreases murine IFITM3 antiviral activity but is not required for human IFITM3 activity (Fig. 4 and Figs. S5 and S6). Our results are consistent with previous IFITM mutagenesis and antiviral activity studies (21, 22, 27, 32, 35), but demonstrates that antiviral activity is directly correlated to S-fatty acylation levels and that dually S-fatty acylated IFITM3 at Cys72 and Cys105 is likely the most active isoform in mammalian cells (Fig. S9). In summary, we demonstrate that NH2OH-mediated APE provides a sensitive and readily accessible method to measure S-fatty acylation levels on diverse proteins in different cell types that should greatly facilitate the analysis of protein S-fatty acylation in physiology and disease.

Fig. S9.

Alignment and conservation of IFITM protein sequences and their relative levels of S-fatty acylation. Comparison of previously compiled database of IFITM family proteins (23), using MEME motif comparison (meme-suite.org), shows relative conservation of residues within the CD225 domain. Cysteines 71, 72, and 105 are differentially palmitoylated (Fig. 4B), represented by the size of the thiol-coupled palmitate beneath the residue frequency plot. Plot prepared using WebLogo (weblogo.berkeley.edu).

Materials and Methods

For APE, cell samples were lysed with 4% (wt/vol) SDS (Fischer) in TEA buffer [pH 7.3, 50 mM triethanolamine (TEA), 150 mM NaCl] containing 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Roche), 5 mM PMSF (Sigma), 5 mM EDTA (Fischer), and 1,500 units/mL benzonase (EMD). The protein concentration of the cell lysate was then measured using a BCA assay (Thermo) and adjusted to 2 mg/mL with lysis buffer. Typically, 200 µg of total protein in 92.5 µL of lysis buffer was treated with 5 µL of 200 mM neutralized TCEP (Thermo) for final concentration of 10 mM TCEP for 30 min with nutation. NEM (Sigma), 2.5 µL from freshly made 1 M stock in ethanol, was added for a final concentration of 25 mM and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Reductive alkylation of the proteins was then terminated by methanol-chloroform-H2O precipitation (4:1.5:3) with sequential addition of methanol (400 µL), chloroform (150 µL), and distilled H2O (300 µL) (all prechilled on ice). The reactions were then mixed by inversion and centrifuged (Centrifuge 5417R, Eppendorf) at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. To pellet the precipitated proteins, the aqueous layer was removed, 1 mL of prechilled MeOH was added, the Eppendorf tube inverted several times and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then decanted, and the protein pellet washed once more with 800 µL of prechilled MeOH, centrifuged again, and dried using a speed-vacuum (Centrivap Concentrator, Labconco) To ensure complete removal of NEM from the protein pellets, the samples were resuspended with 100 µL of TEA buffer containing 4% SDS, warmed to 37 °C for 10 min, briefly (∼5 s) sonicated (Ultrasonic Cleaner, VWR), and subjected to two additional rounds of methanol-chloroform-H2O precipitations, as described above.

For hydroxylamine (NH2OH) cleavage and mPEG-maleimide alkylation, the protein pellet was resuspended in 30 µL TEA buffer containing 4% SDS, 4 mM EDTA and treated with 90 µL of 1 M neutralized NH2OH (J. T. Baker) dissolved in TEA buffer pH 7.3, containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (Fisher) to obtain a final concentration of 0.75 M NH2OH. Protease inhibitor mixture or PMSF should be omitted, as these reagents can interfere with the NH2OH reactivity. Control samples not treated with NH2OH were diluted in 90 µL TEA buffer with 0.2% Triton X-100. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with nutation. The samples were then subjected to methanol-chloroform-H2O precipitation, as described above, and resuspended in 30 µL TEA buffer containing 4% SDS, 4 mM EDTA, warmed to 37 °C for 10 min, and briefly (∼5 s) sonicated and treated with 90 µL TEA buffer with 0.2% Triton X-100 and 1.33 mM mPEG-Mal (5 or 10 kDa; Sigma) for a final concentration of 1 mM mPEG-Mal. Samples were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with nutation before a final methanol-chloroform-H2O precipitation. Dried protein pellets were resuspended in 50 µL 1× Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad) and then heated for 5 min at 95 °C. Typically, 15 µL of the sample was loaded in 4–20% Criterion-TGX Stain Free polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad), separated by SDS/PAGE, and analyzed by Western blot. For Western blots, primary antibodies used were anticalnexin (1:2,000 ab22595; Abcam), anti-pan Ras (1:500; Ras10, Millipore), anti-mouse IFITM3 (1:1,000; ab15592, Abcam), anti-FLAG (1:1,000; F1804, Sigma), anti-HA (1:1,000; ab9134, Abcam), and HRP-conjugated anti-HA (3F10, Roche). Secondary antibodies used were HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (DC03L, Calbiochem), and goat anti-mouse (ab97023, Abcam). Protein detection was performed with ECL detection reagent (GE Healthcare) on a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Imaging System.

Other materials and methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Transfections.

HEK293T, HeLa, and Raw264.7 cells were obtained from ATCC. For transfection of HEK293T or HeLa cells, near confluent six-well plates were transfected with 1 µg of plasmid DNA using 3 µL of Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life Technologies). After 24 h, cells were collected by scraping, centrifuged at 500 × g for 2 min, washed with 1× PBS, snap-frozen in dry ice/ethanol bath, and stored at −80 °C for future use. For NIH 3T3 cells, near confluent six-wells plates were transfected with 1 µg of plasmid DNA with 3 µL of Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Life Technologies). After 6 h, the media was replaced with fresh media to reduce toxicity of the Lipofectamine reagent. After 24 h the cells were collected and stored for future use at −80 °C: LPS (500 ng/mL, Enzo Life Sciences) and IFN-γ (100 U/mL IFN-y, Thermo).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

All cysteine mutants were generated using the QuikChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent). The alanine codon GCA was used for all IFITM3 mutations. The serine codon TCC was used for all HRas mutations. Specific primers used for mutagenesis are shown below.

mIFITM3 C71A ATACACTCTTCATGAACTTCGCATGCCTGGGCTTCATAGCCTATGCC

mIFITM3 C72A ATACACTCTTCATGAACTTCTGCGCACTGGGCTTCATAGCCTATGCC

mIFITM3 C71, 72A ATACACTCTTCATGAACTTCGCAGCACTGGGCTTCATAGCCTATGCC

mIFITM3 C105A CCTACGCCTCCACTGCTAAGGCACTGAACATCAGCACCTTGGTC

HRas C181S GTGGCCCCGGCTCCATGAGCTGCAA

HRas C184S CGGCTGCATGAGCTCCAAGTGTGTGCTCT

HRAS C181,184S GGCCCCGGCTCCATGAGCTCCAAGTGTGTGC

ABE.

The ABE protocol was performed as described previously (12). Following cell lysis, 400 µg of total cell lysate resubjected to reductive alkylation with TCEP and NEM, as described above for the APE protocol. After the final methanol-chloroform-H2O precipitation, the protein pellet was resuspended in 100 µL 4% SDS in 50 mM TEA, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.3, and 1 mM EDTA. The samples were split into two 50-µL aliquots and treated with 1 M NH2OH or control buffer (200 µg per condition). For the NH2OH-treated sample, 150 µL NH2OH-HPDP-biotin buffer [for 160 µL of buffer: 3.2 µL of HPDP-Biotin (50 mM stock in DMSO, Sigma), 36.8 µL of dimethylformamide (DMF, Fisher Scientific), 3.2 µL of 10% Triton X-100 in H2O, 112 µL of 1 M NH2OH in H2O pH 7.3, 4.8 µL H2O] was added to the sample for a final concentration of 0.75 M NH2OH, 1% SDS (lysate:NH2OH-HPDP-biotin buffer 1:3). For the NH2OH− control, the samples were treated with 150 µL of HPDP-biotin buffer [for 160 µL of buffer: 3.2 µL of HPDP-Biotin (50 mM stock in DMSO), 36.8 µL of DMF, 3.2 µL of 10% Triton X-100 in H2O, 16 µL of 500 mM TEA, 1.5 M NaCl pH 7.3, 101.8 µL H2O] was added to the negative control sample for a final concentration of 1% SDS (lysate:buffer 1:3). The mixture was incubated at room temperature with end-over-end rotation for 1 h. Proteins were precipitated (methanol-chloroform-H2O precipitation) and resuspended in 50 µL 4% SDS 50 mM TEA pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (final concentration 4 mg/mL). Next, 150 µL HPDP-biotin low concentration buffer [for 300 µL of buffer: 1.2 µL of HPDP-Biotin (50 mM), 13.8 µL of DMF, 6 µL of 10% Triton X-100 in H2O, 30 µL of 500 mM TEA, 1.5 M NaCl pH 7.3, 249 µL H2O] was added to both samples (HPDP-biotin:lysate 3:1). The samples were incubated at room temperature with end-over-end rotation for 1 h, subjected to methanol-chloroform-H2O precipitation as described above, and resuspended in 100 µL 0.2% SDS, 0.2% Triton X-100, 50 mM TEA, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.3.

High-affinity streptavidin-agarose beads (Thermo; 20 µL of bead slurry/200 µg of protein) were washed with 50 mM TEA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, pH 7.3 (3×). The resuspended samples were then added to the beads and incubated at room temperature with end-over-end rotation for 90 min. The supernatant from the beads was decanted and boiled with 4× Laemmli sample buffer (LSB) (supernatant:LSB:BME 3:1:0.1) at 95 °C for 5 min. The beads were washed with 1% SDS in PBS for 2 min, and centrifuged at 1,700 × g for 1 min (2×). The beads were then washed in 4 M Urea (Sigma) in PBS (3×), PBS (3×). The beads were boiled at 95 °C for 10 min with 1× Laemmli sample buffer (LSB:BME:4% SDS 50 mM TEA, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.3, 0.9:0.1:3), separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by Western blot. Typically, 40 µg of protein were loaded on the gel.

Acyl-RAC.

The acyl-RAC protocol was performed as described previously (13). Following reductive alkylation of total lysate (400 µg) with TCEP and NEM, as described above for the APE and ABE, the samples were resuspended in 50 µL 4% SDS, 50 mM TEA, 150 mM, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.3. The samples were split into two 25 µL aliquots − or + NH2OH (200 µg per condition). For the NH2OH-treated sample, 75 µL NH2OH 1 M, 0.2% Triton X-100, pH 7.3 in H2O was added to the “+NH2OH” sample for a final concentration of 0.75 M NH2OH, 1% SDS (lysate:NH2OH solution 1:3). For the negative control not treated with NH2OH, 75 µL 50 mM TEA, 0.2% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.3 was added to the samples (“−NH2OH”) for a final concentration of 1% SDS (lysate:buffer 1:3). To capture proteins with free thiols, thiol-Sepharose beads 6B (T8387, Sigma) were soaked in 1 mL H2O for 30 min. Beads were washed three times with 0.5 mL of 50 mM TEA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, pH 7.3. Each sample (100 µL of ± NH2OH) was added to the thiol-Sepharose beads (200 µg of proteins/6.25 mg thiol-Sepharose beads) and incubated at room temperature for 3 h with end-over-end rotation. The supernatants from the beads were decanted and boiled with 4× Laemmli sample buffer (LSB:BME:supernatant 0.9:0.1:3) for 5 min. The beads were washed with 1% SDS in PBS (3 × 2 min), 4 M Urea in PBS (3×), PBS (3×). Beads were boiled at 95 °C for 10 min with 1× Laemmli sample buffer (LSB:BME:4% SDS 50 mM TEA, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.3, 0.9:0.1:3), separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by Western blot. Typically, 40 µg of protein were loaded on the gel.

Metabolic Labeling and in-Gel Fluorescence Profiling.

For metabolic labeling of cells with alkyne-palmitic acid reporter, alk-16 (10), HEK293T cells transfected with HA-HRas constructs or NIH 3T3 cells transfected with HA-mIFITM3 constructs were incubated for 2 h with 50 µM alk-16 in DMEM containing 2% (vol/vol) charcoal-dextran stripped FBS (Lot: AZA180873, HyClone). Cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed once in PBS, pelleted and lysed in 1% (wt/vol) Brij 97 (Sigma) in 50 mM TEA 150 mM NaCl pH 7.3 with 5× concentration of EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). Total protein concentration was measured by BCA assay (Life Tech). For immunoprecipitation, 200 μg of total protein was added to 20 μL of anti-HA antibody-conjugated agarose (Sigma) in a total volume of 250 μL and rocked at 4 °C for 16 h. Agarose beads were washed twice by resuspension in 1 mL of wash buffer [1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate (Sigma), 0.1% SDS in 50 mM TEA, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.3] and centrifuged at 3,500 × g for 30 s. The beads were then resuspended in 20 μL of 1% (wt/vol) Brij in in 50 mM TEA 150 mM NaCl pH 7.3 and 5 μL of CuAAC reactant solution [0.5 μL of 5 mM azido-rhodamine (final concentration 200 μM), 1 μL of 50 mM freshly prepared CuSO4·5H2O in H2O (final concentration 2 mM, Sigma), 1 μL of 50 mM freshly prepared TCEP (final concentration 2 mM) and 2.5 μL of 2 mM Tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]amine (TBTA) (final concentration 200 μM)]. Beads were rocked with the CuAAC reactant solution at room temperature for 1 h and washed twice with wash buffer, as described above. The proteins were eluted addition of 30 μL 1× Laemmli sample buffer (LSB:BME: 4% SDS 50 mM TEA, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.3, 1:0.1:3), heated for 5 min at 95 °C, and separated by SDS/PAGE. In-gel fluorescence scanning was performed using a Typhoon 9400 imager (Amersham Biosciences). Western blots for HA-tagged proteins were performed using an anti-HA tag-HRP conjugated antibody (1:1,000; Roche).

Influenza Virus Infection.

NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo) overnight in 12-well plates using 1 μg of plasmid per well. Media was removed and replaced with 400 μL of media ± influenza virus strain A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1, commonly referred to as PR8) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 for each well. Infection was allowed to proceed for 18 h. Cells were collected and fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min and blocked with 2% FBS in PBS for 20 min. All antibody staining and washing was performed using the 0.1% Triton X-100 solution. Staining with anti-HA antibody (HA.11, Covance; 1:1,000) was performed for 20 min at room temperature followed by three washes and staining with anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to Alexafluor-488 (Life Technologies; 1:1,000). After an additional three washes, cells were stained with anti-influenza NP antibody (ab20343, Abcam; 1:300) that was directly conjugated in-house to Alexafluor-647 using the 100 μg antibody labeling kit from Life Technologies. Samples were analyzed using a Becton Dickinson FACSCanto II flow cytometer and HA+ cells were analyzed for the percentage of cells staining positive for influenza NP indicating cellular infection using Flowjo software, as previously described (21).

Immunofluorescence Analysis.

For the analysis of mIFITM3 colocalization with endosomal/lysosomal markers, 50,000 NIH 3T3 cells per well were plated in a 24-well plate, and cotransfected the next day with 0.25 μg HA-IFITM3 and 0.25 μg of either GFP-Rab5, GFP-Rab7 (54244, Addgene), or LAMP1-GFP (34831, Addgene) with 1.5 μL Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo) for 4 h, then incubated with fresh media for an additional 12 h. Cells were fixed for 15 min with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, washed 3× with PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% saponin in PBS for 10 min, and blocked for 60 min with 1% BSA in PBS. All antibody staining and washing was performed with 0.1% saponin in PBS. Cells were incubated with goat anti-HA antibody (1:1,000; ab9134, Abcam) in 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. After three, 5-min washes, samples were incubated with donkey anti-goat antibody conjugated to Alexafluor-647 (1:1,000; A-21447, Invitrogen) in 1% BSA. Cells were washed, and mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). Images were obtained from an Inverted Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope, and processed with ImageJ. Pearson coefficient was calculated using Imaris 8 software.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a National Science Foundation graduate fellowship (to A.P.); a Marie Sklodowska-Curie actions for a postdoctoral fellowship (to E.T.); National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grants R00AI095348 and R56AI114826 (to J.S.Y.); Starr Cancer Consortium Grant I7-A717 (to H.C.H.); and National Institutes of Health-National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant R01GM087544 (to H.C.H.). X.Y. is a graduate student in the Tri-Institutional Program in Chemical Biology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1602244113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chamberlain LH, Shipston MJ. The physiology of protein S-acylation. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(2):341–376. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng T, Thinon E, Hang HC. Proteomic analysis of fatty-acylated proteins. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;30:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang X, et al. Heterogeneous fatty acylation of Src family kinases with polyunsaturated fatty acids regulates raft localization and signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(33):30987–30994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brett K, et al. Site-specific S-acylation of influenza virus hemagglutinin: the location of the acylation site relative to the membrane border is the decisive factor for attachment of stearate. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(50):34978–34989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.586180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukata Y, Fukata M. Protein palmitoylation in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(3):161–175. doi: 10.1038/nrn2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Palmitoylation: Policing protein stability and traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(1):74–84. doi: 10.1038/nrm2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin DT, Conibear E. Enzymatic protein depalmitoylation by acyl protein thioesterases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43(2):193–198. doi: 10.1042/BST20140235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin DT, Conibear E. ABHD17 proteins are novel protein depalmitoylases that regulate N-Ras palmitate turnover and subcellular localization. eLife. 2015;4:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hang HC, Wilson JP, Charron G. Bioorthogonal chemical reporters for analyzing protein lipidation and lipid trafficking. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(9):699–708. doi: 10.1021/ar200063v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charron G, et al. Robust fluorescent detection of protein fatty-acylation with chemical reporters. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(13):4967–4975. doi: 10.1021/ja810122f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang R, et al. Neural palmitoyl-proteomics reveals dynamic synaptic palmitoylation. Nature. 2008;456(7224):904–909. doi: 10.1038/nature07605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan J, Roth AF, Bailey AO, Davis NG. Palmitoylated proteins: Purification and identification. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(7):1573–1584. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forrester MT, et al. Site-specific analysis of protein S-acylation by resin-assisted capture. J Lipid Res. 2011;52(2):393–398. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D011106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocks O, et al. An acylation cycle regulates localization and activity of palmitoylated Ras isoforms. Science. 2005;307(5716):1746–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.1105654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakkaraju AK, et al. Palmitoylated calnexin is a key component of the ribosome-translocon complex. EMBO J. 2012;31(7):1823–1835. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynes EM, et al. Palmitoylated TMX and calnexin target to the mitochondria-associated membrane. EMBO J. 2012;31(2):457–470. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomä NH, Niculae A, Goody RS, Alexandrov K. Double prenylation by RabGGTase can proceed without dissociation of the mono-prenylated intermediate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(52):48631–48636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howie J, et al. Substrate recognition by the cell surface palmitoyl transferase DHHC5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(49):17534–17539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413627111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry SC, Schmidt EA, Fessler MB, Taylor GA. Palmitoylation of the immunity related GTPase, Irgm1: Impact on membrane localization and ability to promote mitochondrial fission. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charrin S, et al. Differential stability of tetraspanin/tetraspanin interactions: Role of palmitoylation. FEBS Lett. 2002;516(1-3):139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yount JS, Karssemeijer RA, Hang HC. S-palmitoylation and ubiquitination differentially regulate interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3)-mediated resistance to influenza virus. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(23):19631–19641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yount JS, et al. Palmitoylome profiling reveals S-palmitoylation-dependent antiviral activity of IFITM3. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(8):610–614. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerscher O, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M. Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:159–180. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Liu J, Li M, Yang H, Zhang C. Evolutionary dynamics of the interferon-induced transmembrane gene family in vertebrates. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hickford D, Frankenberg S, Shaw G, Renfree MB. Evolution of vertebrate interferon inducible transmembrane proteins. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feeley EM, et al. IFITM3 inhibits influenza A virus infection by preventing cytosolic entry. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(10):e1002337. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.John SP, et al. The CD225 domain of IFITM3 is required for both IFITM protein association and inhibition of influenza A virus and dengue virus replication. J Virol. 2013;87(14):7837–7852. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00481-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu J, Deutsch C. Pegylation: A method for assessing topological accessibilities in Kv1.3. Biochemistry. 2001;40(44):13288–13301. doi: 10.1021/bi0107647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgoyne JR, Oviosu O, Eaton P. The PEG-switch assay: A fast semi-quantitative method to determine protein reversible cysteine oxidation. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2013;68(3):297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rexach JE, et al. Quantification of O-glycosylation stoichiometry and dynamics using resolvable mass tags. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(9):645–651. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortiz-Meoz RF, Merbl Y, Kirschner MW, Walker S. Microarray discovery of new OGT substrates: The medulloblastoma oncogene OTX2 is O-GlcNAcylated. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(13):4845–4848. doi: 10.1021/ja500451w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narayana SK, et al. The interferon-induced transmembrane proteins, IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3 inhibit hepatitis C virus entry. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(43):25946–25959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.657346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng T, Hang HC. Bifunctional fatty acid chemical reporter for analyzing S-palmitoylated membrane protein-protein interactions in mammalian cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(2):556–559. doi: 10.1021/ja502109n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsukamoto T, et al. Role of S-palmitoylation on IFITM5 for the interaction with FKBP11 in osteoblast cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hach JC, McMichael T, Chesarino NM, Yount JS. Palmitoylation on conserved and nonconserved cysteines of murine IFITM1 regulates its stability and anti-influenza A virus activity. J Virol. 2013;87(17):9923–9927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00621-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]